Asian Textile Studies

Contents

East Flores Textiles

Kecamatan Titehena

Titehena History

Titehena Ethnography

Titehena Weaving

Titehena Textiles

Kewatek Mitén

Kewatek Méan

Senai Miten

The Mét Belt

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

East Flores Textiles

The eastern end of Flores Island, now the mainland part of East Flores Regency, has a rich tradition of warp ikat textiles. Many of its Lamaholot weavers remain skilled spinners and natural dyers and still produce subtly decorated, multi-striped hand-spun cotton textiles for both women and men.

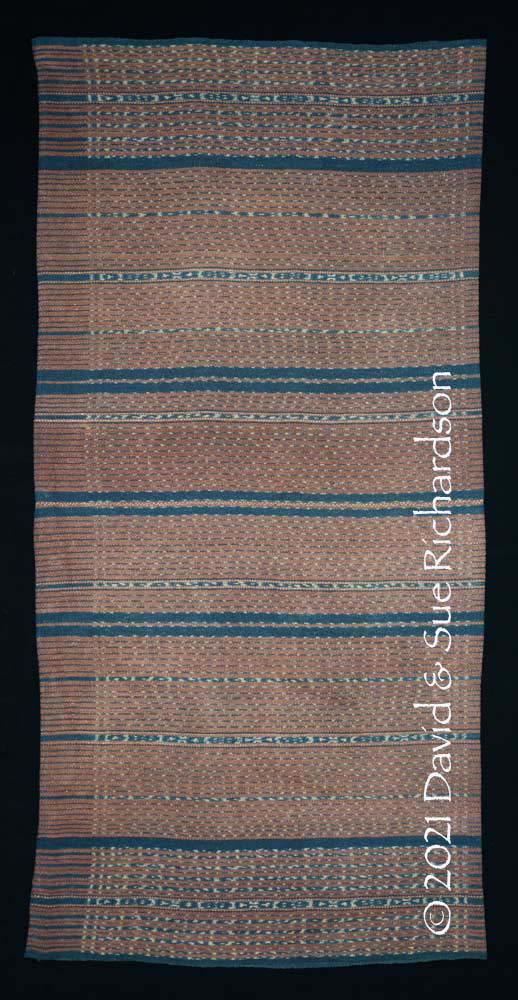

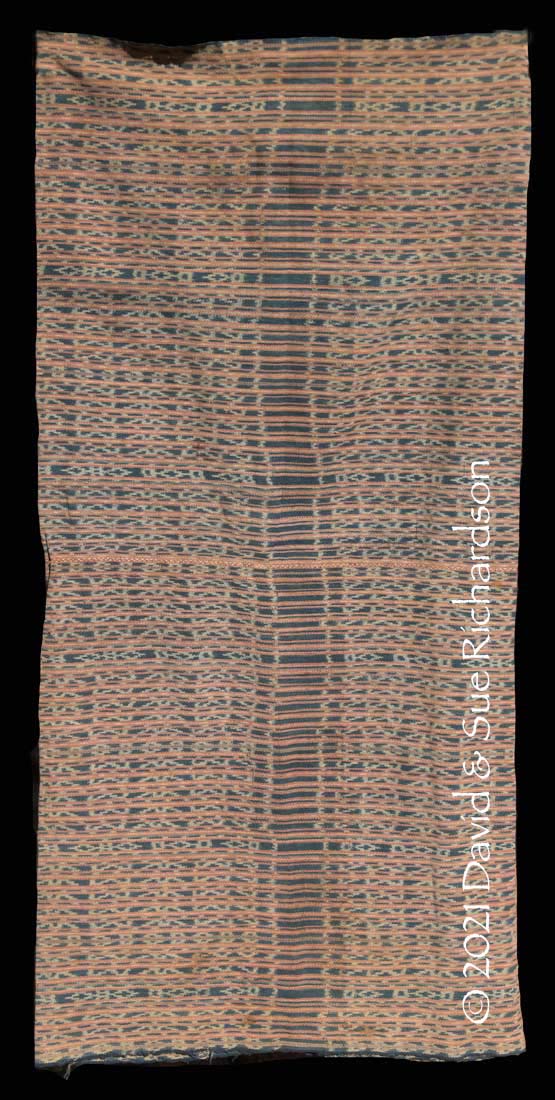

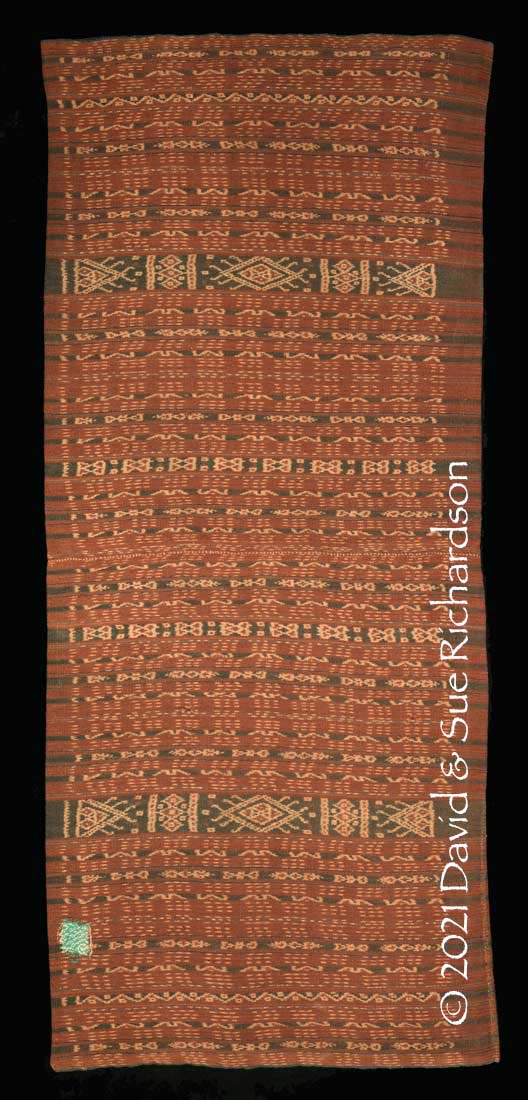

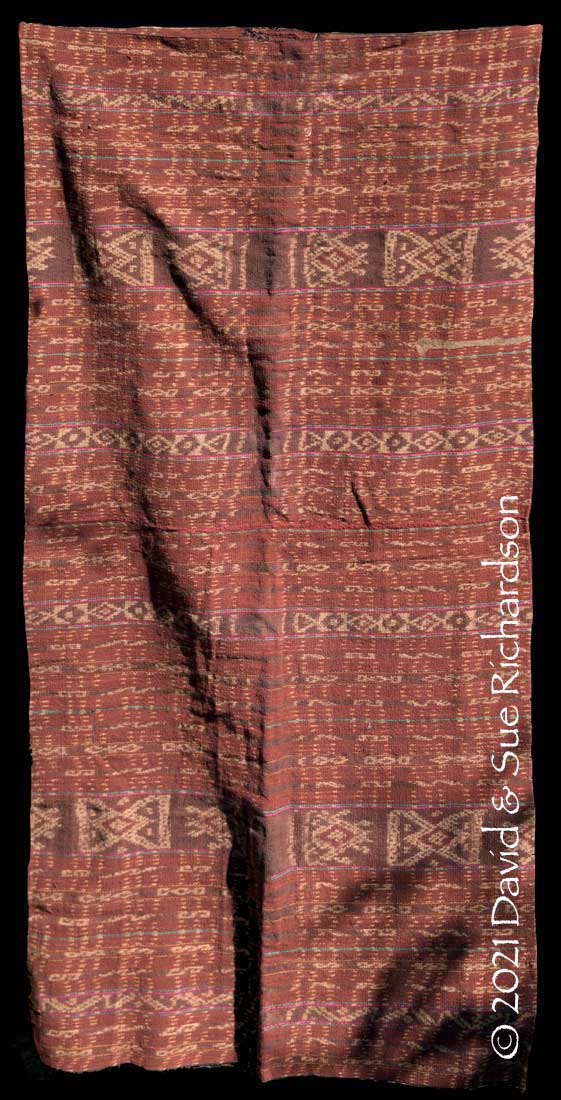

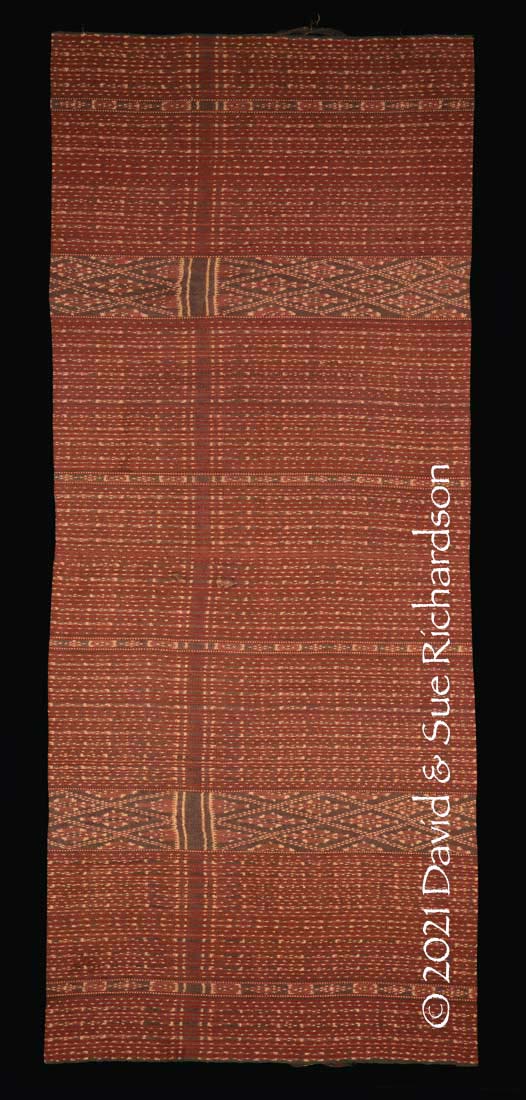

An everyday woman’s hand-spun kewatek sarong that was already of some considerable age when we collected it on Flores in 1991. It is very similar to the kewatek kenuma made in Ilé Mandiri and the keriot pasan made in Demon Pagong. Richardson Collection

Unfortunately much of the literature published on Indonesian textiles takes a simplistic approach to this complex region. Armchair collectors unfamiliar with the region acquire local textiles from dealers or auctions with no provenance and often classify them as Ilé Mandiri, not realising that the eastern end of Flores Island has many different weaving areas, each with their own textile types, design styles and textile nomenclature. If you do not know in which village a textile was produced in this region it is impossible to label it with its correct name.

As emphasised by Ruth Barnes: ‘just as the dialect of Lamaholot may change from one village to the next, so the interpretation of the form and function of ikat textiles can be equally varied’ (1994, 191).

There are six separate weaving areas in eastern Flores:

| Tanjung Bunga |

| Ilé Mandiri, also known as Baipito |

| Léwoléma |

| Demon Pagong |

| Titehena and |

| Ilé Bura, also known as Lewotobi |

Map of the kecamatan of eastern Flores, with the six weaving areas highlighted

(Map courtesy of Kabupaten Flores Timur)

It is reputed that the ikat produced in the previously remote peninsula of Tanjung Bunga was once the region’s best. Mysteriously it appears that the weaving of traditional textiles died out in this area many decades ago. Fortunately it still continues in the other five areas.

Return to Top

Kecamatan Titehena

Titehena is one of nineteen kecamatan or districts in Kabupaten Flores Timur (East Flores Regency, referred to locally as Flotim) and one of the eight that are situated on the island of Flores itself. Located roughly 25km west of Larantuka, it stretches from Konga Bay in the south to Hading Bay and the Flores Sea in the north. Its landscape is heavily forested and is dominated by two small mountains, Ilé Tenawahang (1060m) in the east and Ilé Gora (650m) in the west. It has a land area of 155 square kilometres. The administrative centre is Kampong Lato in Desa Wolowara.

The terrain of East Flores (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Some of the important kampongs in Kecamatan Titehena

The trans-Flores highway (formerly the Flores Way) loops around Titehena’s southern coastline and is connected to the north coast road by a link road built in the centre of the wide low-lying valley that separates the two upland regions. On the north coast, Lato beach is a local beauty spot.

Konga Island located ½km offshore was originally uninhabited and used to graze a herd of goats belonging to the Raja of Larantuka. Today it is the base for a Japanese-owned pearl farm. Sadly both Konga Bay and the north coast of Titehena suffer from significant pollution from plastic waste. The coral reef along the north shore has been recklessly damaged by dynamite fishing.

The view across western Solor Island towards Konga Bay on Flores Island and tiny Konga Island. The stratovolcano on the left is Ilé Lewotobi

The view south across the Flores and Lewotobi Straits, with Solor Island on the left, Lewotobi volcano centre and Konga Bay on the right

View towards Konga Island and the south coast of Titehena around Konga Bay

The Lewotobi stratovolcano just appears on the left

Titehena is divided into fourteen desa or village regions:

| Desa | Administrative Kampong |

| Adabang | Pagong |

| Bokang-Wolomatang | Bokang |

| Duli Jaya | Duli |

| Dun Tana Lewoingu | Rian Duli |

| Ile Gerong | Gerong |

| Kobasoma | Kanada |

| Konga | Konga |

| Leraboleng | Leworok |

| Lewoingu | Eputobi |

| Lewolaga | Lewolaga |

| Serinuho | Serinuho |

| Tenawahang | Tenawahang |

| Tuakepa | Tuakepa |

| Watowara | Lato |

The fourteen desa of Kecamatan Titehena

The population of Titehena was 11,685 in 2016, with 5,715 males and 5,970 females (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2018).

Most residents are farmers, the main crops being cassava, maize and rice. Important secondary crops are sweet potatoes, peanuts, cashew nuts, coconuts, coffee, candlenut and cocoa. Goats and pigs are the most important livestock. The 2016 livestock survey identified 6,600 pigs, 5,000 goats, 500 cows and 12,500 chickens.

Return to Top

Titehena History

Much of the history of this rural region is lost in time. Linguists infer that its original Austronesian population migrated west from Lembata via Adonara and Solor (Fricke and Klamer 2018). Many of the villages in the northern part of Titehena appear to be relatively new, suggesting that in the past the population was mainly confined to the south around Konga Bay.

A colourful oral legend outlining the history of the Rajas of Larantuka suggests that before the formation of the Rajadom, each district and village was separately governed by its own district head or kakang (Barnes 2008, 345). The first ruler, Sira Demon, a grandson of an immigrant from Waihele in central Timor, appears to have peacefully extended his rule over ten separate Lamaholot districts. Some of these, including Lewoingu in present-day Titehena, were on mainland East Flores while the others were on Adonara, Solor and Lembata.

Some of the first European visitors in the early seventeenth century recorded that the Lamaholot were divided into two antagonistic groups, the Demon and the Paji, a schism echoed in local legends (De Sá 1956, 484). The Demon were the inland ata kiwan, swidden agriculturalists with pagan beliefs who were subject to the Raja of Larantuka. The Paji were later arrivals, coastal Muslims dependant on fishing who were subject to the Raja of Adonara. The population of the Konga Bay area would have been Demon.

The Portuguese established a fortified Dominican mission in east Solor and a settlement developed around it inhabited by local Solorese Christians, some of whom had mixed indigenous-European parentage. Their economy became increasingly dependant on trading sandalwood harvested on Timor Island. When the Dutch conquered the fort and surrounding town in 1613, some of the occupants settled across the Strait in Larantuka, creating a Catholic enclave allied to the white Portuguese. They called themselves Larantuqueiros, although the Dutch disparagingly referred to them as black Portuguese. They would later be referred to as Topasses, after their distinctive Portuguese headwear.

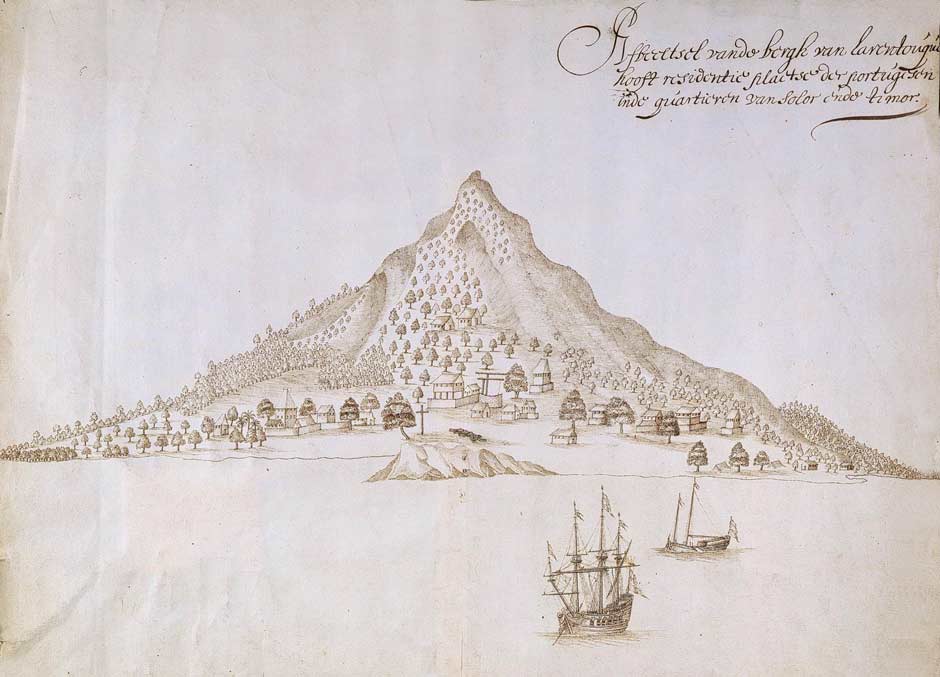

Fort Henricus on Solor in about 1614 (Isaac Commelin, 1646, Begin ende Voortgangh van de Vereenighde Nederlantsch Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie, vol. 4.)

In 1620 the Dutch on Solor, allied with local Muslims, attacked Larantuka and burnt down the church and many houses (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 82).

As the population of Larantuka expanded some families relocated to two new coastal settlements – Konga facing Konga Island, a location where the Portuguese previously based on Solor used to obtain wood, and Wureh on the western tip of Adonara just across the narrow strait facing Larantuka. Sadly the historical record provides little information about the native villages of Titehena. Our only insight into that region comes from numerous reports about the southernmost village of Konga which, along with Larantuka and Wureh on Adonara, was known as a ‘kampong Malay’.

A mysterious pair of iron cannons discovered on Lato beach

(Image courtesy of Pangky Sogemaking)

In addition to the Topasses, merchants from Makassar were also successfully sourcing sandalwood directly from Timor. After the VOC agreed to obtain its supplies from them, the Sultan of Gowa set out in 1641 to destroy the small Topass base at Larantuka. A fleet of over 5,000 men attacked and incinerated the town and, after desecrating its religious images, the church. They sailed on to Timor, ravaging the coast for slaves (Hägerdal 2012, 85). After returning to Makassar, the Sultan was assassinated by his wife, so his initiative to eliminate the Topasses from the sandalwood trade came to nothing.

Following the Dutch conquest of the strategically located port of Malacca in the same year, many local Portuguese fled by sea – some to Makassar and others to Singapore, Ambon and Maumere, the latter continuing on to Larantuka. However once they landed at Larantuka the local population attacked them. After being divided into two groups, one was sent to Konga and the other to Wureh. After negotiating with the existing inhabitants of those villages they were assigned areas to settle. In Konga this led to the formation of two social groups, suku sau and suku Malacca (Viola 2013, 229). The immigrant Portuguese married local women and their offspring maintained their Portuguese ancestry. The Konga settlement was administered by a council composed of the heads of the local Portuguese families (Daus 1989, 46).

Under its retired military leader capitão-mor Francisco Carneiro Sequeira, the black Portuguese community at Konga gradually became a separate commercial and political entity alongside Larantuka with both a secular and mercantile character – separated from the Catholic mission clerics and increasingly linked to the trade in Timorese products (Viola 2014, 193). Konga grew into an important sandalwood warehouse, trading with the Dutch, Makassar and even Macau. In 1650 in an attempt to improve their position in the sandalwood trade, some 2,000 black Portuguese Catholics from Konga supported the ruler of the Sonba’i tribal confederation on Timor against his enemies (Andaya 2010, 399).

Like the Portuguese before them, the Dutch based at Fort Henricus would sail across to Konga Bay to obtain their supplies of wood. In 1651 a small Dutch party was attacked at Konga by Portuguese troops under the command of Sequeira (Hägerdal 2012, 104). Nineteen Dutch were taken prisoner and only two escaped back to the fort (Viola 2013, 203). The fort commander Ter Horst made great efforts to have his men released, even travelling to Larantuka to directly appeal to the Portuguese. In early 1653 the Dutch VOC retaliated by dispatching a naval squadron to Flores to attack the village. Recognising the threat, its inhabitants fled into the forest for safety with their possessions. However their church was incinerated (Viola 2014, 205). It was rebuilt following the intervention of the Dominican Friar Frei João.

In 1657 the VOC relocated their base of operations from Fort Henricus on Solor to Fort Concordia in the Bay of Kupang on Timor and their influence in the Solor-East Flores region began to wane. By now the Larantuqueiros/Topasses had two separate bases of power controlled by two wealthy local families – Larantuka led by António Hornay, and Lifao on the north coast of Timor led by Matheus da Costa (Andaya 2010, 406; Hägerdal 2012, 140).

The Dutch siege of Makassar in 1660 forced the Sultan of Gowa to agree to the expulsion of all of the Portuguese and other Europeans from the port. This led to yet more Portuguese arriving to join the Topasses in the Larantuka and Timor regions. One year later the Dutch and Portuguese agreed a truce, recognising the Portuguese ownership of Larantuka, the Dutch ownership of Fort Henricus and both nations rights to trade with Timor (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 85).

The town of Larantuka in 1672, the main Portuguese settlement in the Solor-Timor region

(Leupe catalogue, Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam)

In an attempt to control local trade, the Larantuqueiros established a bazaar at Konga, where their allies in the Sikka region could trade and obtain foreign goods (Hägerdal 2012, 176). In the 1670s a ship from Lamahala on the south coast of Adonara anchored at Konga to purchase rice and other provisions, but the local merchants forbade them trading and their cargo was confiscated. Apparently António Hornay had issued instructions to the residents of Konga that they were only to trade with the mountain villages (Hägerdal 2012, 175). The Catholic Larantuqueiros of Konga had a close relationship with their neighbouring native villages, on whom they totally depended to obtain their rice and other vital supplies.

The death of António Hornay in 1693 left a void that led to growing instability and chaos in the Topass domains. In 1699 Gaspar Chase, a Topass leader in Konga, made a bid to become the capitão mor of Larantuka. However when Domingos da Costa, the son of the late Matheus da Costa, sent troops to challenge him, he fled to Lifao (Antaya 2010, 408).

In the early eighteenth century the power of the Dutch VOC in the Solor and Timor regions was weakening and in 1749 the Topasses on Timor, along with their Sonba’i allies, attempted to overrun the Dutch base at Fort Concordia, Kupang. The Dutch put up a strong defence at Penfui just east of Kupang and the Topasses were repelled. The resulting stalemate left the Dutch ensconced in Fort Concordia, but without any significant influence beyond Kupang, and the Topasses free to trade their sandalwood and to expand their involvement in the slave trade on both Timor and Sumba Islands.

When the Dutch resumed their colonial rule in 1816, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, they continued to operate a policy of minimal direct involvement in the Flores-Solor region. However they remained irritated by two powerful competitors, the Endenese and the Topasses, both of whom were actively engaged in the local slave trade. In November 1836 the Dutch Resident on Timor discovered that merchants from Larantuka and Ende had supplied 1,000 slaves to Timor. Concerned about Endenese and Topass piracy, and unable to stop the local slave trade, the Dutch dispatched the corvette Boreas and the brig of war Siwa from Kupang and shelled and incinerated Larantuka before moving on to Ende (Barnes 1996, 15).

This event led to the opening of a dialogue between the Dutch authorities in Kupang and the Portuguese authorities in Dili concerning the disputed colonial sovereignty of Timor, East Flores and the Solor Islands. When José Lopes de Lima arrived as the new Governor of cash-strapped Dili in 1848 he set out to not only resolve the conflict over frontiers, but also at the same time to put the finances of his administration in order. He finalised an agreement with the Dutch Resident in Kupang, Baron van Lynden, in November 1851 to cede Flores, Solor, Adonara, Lembata, Pantar and Alor to the Dutch in return for the enclave of Oecussi and Maubara and Atauru Island in East Timor. Because the islands ceded to Holland were larger than the territories ceded to Portugal, the Dutch would make a payment of 200,000 florins (de Sousa Saidanha 1994, 38-39). Desperate for cash, Lopes de Lima immediately rescinded authority over Flores and the other Solor Islands in return for 80,000 florins. When Lisbon received news about the agreement they were furious and Lopes de Lima was recalled as a traitor but died at sea. However his agreement could not be annulled and a formal treaty of demarcation was finalised in 1854 but only ratified in 1859 as the Treaty of Lisbon.

The Topasses were furious that the white Portuguese in Dili had sold them out to the Dutch. However one of the conditions agreed with Lopes de Lima was that those inhabitants who were Catholic (primarily those in Larantuka, Konga and Wureh) would remain Catholic. This condition was secured in article 10 of the 1859 treaty, which guaranteed religious freedom on both sides (Barnes 2009).

By 1860 Dutch Catholic priests had begun to replace the Portuguese priests who had previously travelled to Flores from Dili (Fox 1980, 241). In 1862/63 one of them, Caspar J.H. Franssen, discovered that there was still a traditional temple in Konga and determined to get rid of it. Clearly Konga was not exclusively Catholic and also accommodated people holding traditional beliefs.

In 1875 E. F. Kleian, the Civiel Gezaghebber of Solor Island, along with his posthouder Ehrich, embarked on an adventurous trek across East Flores and Sikka, despite being advised against travelling by both the Raja of Larantuka Don Gaspar and by the local Catholic pastor Metz (1891, 485-486).

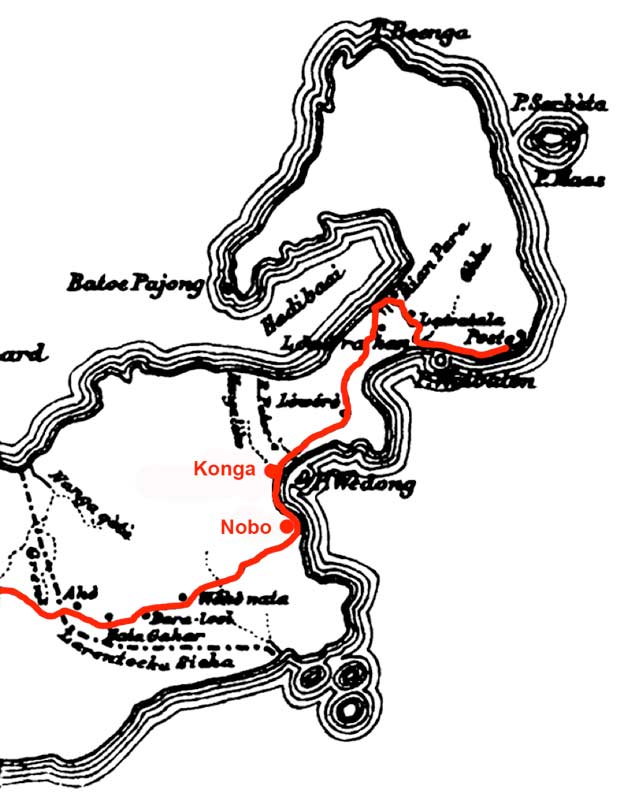

Armed with hand pistols and flintlock guns they set off westwards from Larantuka with seven porters. From Oka Bay they walked north to Lewotalo and then Leworahang on the north coast facing Hading Bay, before turning southwest for a difficult ascent up to the high mountain villages of Lewero and Tuakepa. From there they descended to Konga and Nobo before returning to the north coast of Sikka region and continuing to Maumere, finally travelling south to Léla, Sikka Natal and Paga.

The route of Kleian and Ehrich in June 1875

Tuakepa was almost deserted, the villagers having gone to their gardens, and its 23 houses were in a dilapidated state. The region between Tuakepa and Konga had good soil and plenty of water, yet was uninhabited because of the constant warfare between villages. Although seldom more than a handful of people were killed in such disputes they could endure for several years. As a consequence, villages were built in locations that were more difficult to reach and easier and better to defend.

When Kleian and Ehrich finally reached Tenawahang they encountered a waterfall and continued to a larger river called Nanga, which they feared crossing because there were signs of crocodiles along its banks. Here one of their guides abandoned them because his village was at war with Nobo, just west of Konga.

At that time there was no obvious track or path from Tenawahang to Konga Bay, so they had to hack through thorny thickets to reach the beach and nearby Konga. Konga was a fairly large kampong with 40 houses, all in pretty good condition, a Catholic church and a few chapels. The village chief was surprised to see them as previous visitors had always arrived by sea. Their local economy was based on the production of salt, making earthenware pots, fishing and coconuts, the latter being in great demand because of their high oil content. This local produce was bartered for rice, maize, tobacco and wax with the mountain people. The residents were mostly Roman Catholic and were visited several times a year by the Larantuka clergy.

The visitors were surprised that the village did not grow its own rice, because the land behind the kampong was flat and overgrown with reeds - ideally suited for rice paddy fields. Apparently this had been tried in the past but was abandoned. Then, just as now, there were no buffalos in East Flores, so after burning the reeds the villagers had to trample the mud standing in water up to their knees. Also when the plain was flooded it attracted insects, which then destoyed the maize crops in the mountain villages and created tension with the local people. Interestingly the visitors had difficulties hiring a local interpreter because the residents of Konga were afraid of the mountain people. There was also surprisingly no path from Konga to Nobo, so the travellers were forced to scramble along the beach.

After 1881 Dutch Catholic priests began travelling to Flores in their hundreds, some establishing bases in Larantuka, Konga and Wureh (Daus 1989, 57). They soon began to venture out into the surrounding mountain villages in an attempt to spread the faith. On one such trip in 1882, a Father Zeliswas was joined by the young Don Lorenzo, a member of the Larantuka nobility earmarked to become the next Raja (Steenbrink 2003, 90). Don Lorenzo also accompanied a Father Schweitz on another proselytising visit to the Konga region in 1887, during which he learned of the death of Raja Dominggo and his succession to the Rajadom (Steenbrink 2003, 90).

A Catholic pastor and altar boy (with the lantern) enter a Flores kampong on horseback to visit a sick villager

In the early 1900s the Dutch changed their policy towards the outer islands, introducing a much more hands-on approach. In 1904 the Resident of Timor, F. A. Heckler, arrived in the port of Larantuka on board the government steamship Pelikaan and ordered the troublesome Raja Lorenzo II to join him, whereupon he was arrested and deposed. After being sent as a prisoner to Kupang, he was exiled to Java and temporarily replaced by a puppet. The Dutch set about registering the population, confiscating firearms, imposing taxes and requisitioning corvée labour to construct roads.

In 1908 work began on the construction of the trans-Flores highway that would link Larantuka to Reo, a challenging and ambitious project that would take almost two decades to complete. The route passed around the edge of Konga Bay in the southern part of present-day Titehena. As the road progressed, the inhabitants of the mountain villages were encouraged to move down to new villages that had been built alongside it (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 241).

Local Larantuka officials were tasked with conscripting labourers to work on the new road and for overseeing their progress. Not surprisingly the local villagers strongly opposed these measures, sometimes violently, and the Dutch responded with military force (Dietrich 1985). When the authorities imposed forced labour on the village of Leworok in 1914, their leader, Kuda Duru, led a rebellion against the Dutch during which one Dutch officer was shot. Kuda Duru was captured and later imprisoned in Kupang

In 1912 the acting Raja and his officials chose Servus, the son of Raja Lorenzo II, as the next Raja, a decision consistent with adat. His appointment was endorsed by the local Dutch Controleur A. M. Hens once Servus had signed the Korte Verklaring (Short Declaration). This was a one-sided agreement in which Larantuka recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies (Barnes 2010, 10).

In 1915 the Burgerlijke Openbare Werken (Department of Civil Public Works) of the Netherlands East Indies appointed the civil engineer Charles Constant François Marie Le Roux to oversee the trans-Flores road project, a fortunate choice. During his four years on the island he used the opportunity to photograph the locations and villages along the route and the local people’s daily life, becoming increasingly interested in ethnography rather than road construction.

Building the trans-Flores highway beside the Nanga Geté river at Kringa, in the very southeast of Sikka, just over the border from East Flores (Le Roux 1915)

Fortunately one of the villages that he recorded was kampong Konga, including its small Catholic church and its congregation.

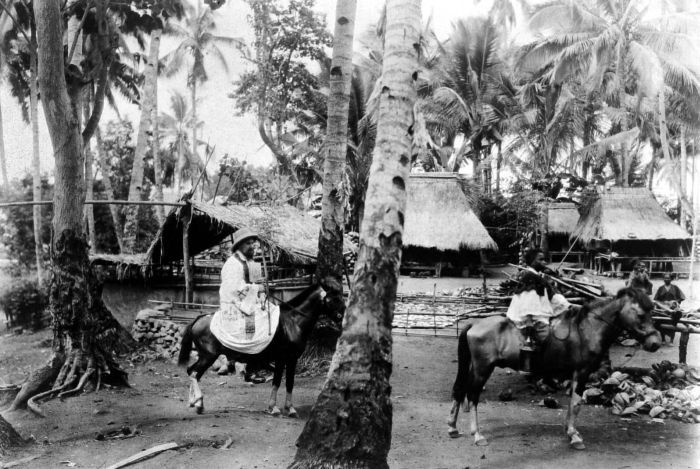

The village of Konga in about 1915, photographed by Charles Le Roux.

(Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Creative Commons)

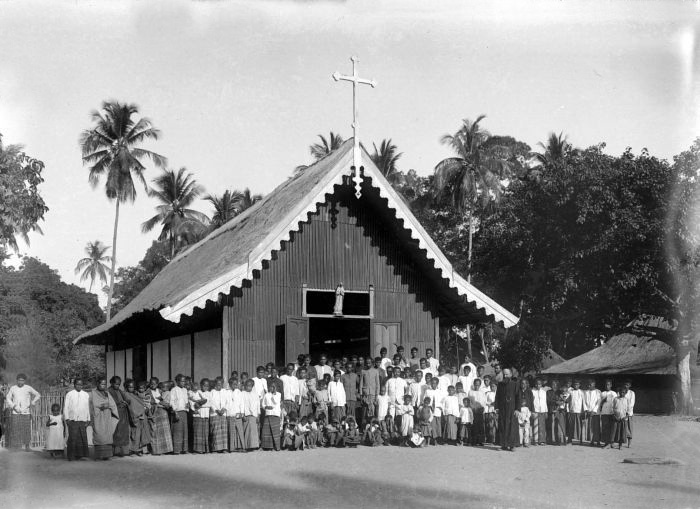

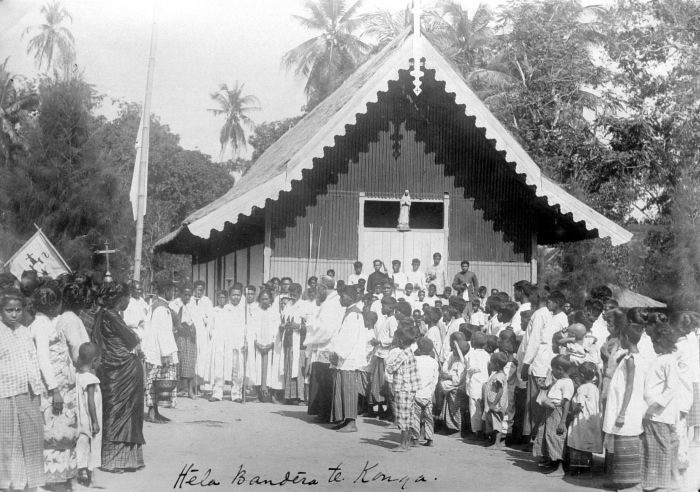

The missionary Pastor J. van der Loo with his congregation at the Roman Catholic Church in Konga (Le Roux, about 1915)

Raising the Flag of the Rosary in front of the Catholic Church in Konga (Le Roux, about 1915)

In January 1929 Ernst Vatter and the Catholic priest Father Strieter rode on horseback around Konga Bay on their way from Bama to Nobo and Lobe Tobi (Lewotobi) via the ‘Flores Way’ Vatter 1932, 142). Although Vatter’s journal includes only a few paragraphs on the region, it does give us a limited glimpse of what life was like at that time.

Vatter described his first view of Konga Bay as a landscape of fairy-tale beauty with the cone of Konga Island ‘untouched by human hands, like an enchanted fairy-tale island, [with] no village and no fields’.

Vatter’s first view of Konga Island, photographed in January 1929

After passing through the densely forested coastal plain they reached the large village Lewolaga, which had a teacher. A dense mangrove forest around the curve of the bay blocked their view of the sea. In recent years, crocodiles had attacked some women and children while they were bathing or fetching water in the bay. During their brief visit to Lewolaga, Vatter managed to acquire two local kewatek sarongs.

The old Christian settlement of Konga was located in a grove of highly productive coconut trees. The soil in this location was extremely fertile but very swampy, so the whole area was badly infected by malaria with an extremely high mortality rate, especially among children. Elephantiasis was also very common. There was a Portuguese brotherhood here, and some families were still in possession of beautiful old images of saints and the Madonna, carved from ivory and wood. Beyond Konga the Flores Way passed between the sea and the slopes of Ilé Muda through an open palm forest with wide, open fields of alang-alang to the south.

At some time after the link road had been constructed between the trans-Flores highway and the north coast, some of the villagers from Leworok, located to the east, relocated to a new settlement named Mananga on the north coast facing Hading Bay. It later became known as Watowara, meaning a stone that stands upright in the storm (wato = stone, wara = storm). The name comes from a pair of stone outcrops on the nearby white sandy beach. In the past they were used for conducting sacrifices for the ancestors.

The stone outcrops on Lato beach

Likewise the village of Tenawahang (literally ‘boat paddle’) 2km south of Watowara was enlarged by another group of villagers who moved from Leworok many years ago.

On 12 December 1992 there was a powerful 7.8 magnitude earthquake about 50km north of Maumere, which caused a major tsunami. A 25-metre high wave smashed into the town of Maumere, devastating 90% of the buildings and killing 1,490 people. Fortunately by the time it reached Lato beach it was from 3.5- to 6.9-metres high, but still powerful enough to destroy Watowara village and kill twelve of its residents. The tsunami created Lake Ranai just behind Lato beach, which has since become a haven for wildlife.

The survivors built the new hamlets of Lato, Leworita and Baujawa further inland some 2km south of the beach. Since then they have become united as dusun Lato within the larger village region of desa Watowara in Kecematan Titehena. Watowara encompasses six other dusun: Baomang, Leworita, Donarita, Mageaman, Ilegorang and Tana Betok.

Return to Top

Titehena Ethnography

The people of East Flores are ethnically Lamaholot and speak one of the 35 Lamaholot dialects that were first identified by Gregorius Keraf in 1978. Prior to 1945 the local people were referred to as the Solorese, although they call themselves the ata kiwan, the people of the interior. The term Lamaholot is recent, having only been adopted by foreign anthropologists and linguists in recent times.

The dialect spoken in Titehena differs from those spoken in Tanjung Bunga, Ilé Mandiri, Léwoléma, Demon Pagong or Lewotobi (Michels 2017, 20). Keraf termed it the Lewolaga dialect, and classified it as one of the ten spoken on mainland East Flores and one of the twenty-three classified as western Lamaholot (Akoli 2010, 18).

As already mentioned, the Lamaholot have long been divided into two antagonistic groups, the Demon and the Paji - the Demon being the inland ata kiwan, swidden agriculturalists with pagan beliefs who were subject to the Raja of Larantuka while the Paji were later arrivals, coastal Muslims dependant on fishing who were subject to the Raja of Adonara. The majority of Titehena residents fall into the Demon category, although today there are a few Muslims, such as those living in Beloteba.

Each village in Titehena is socially divided into patrilineal clans called suku, each one of which has a legend about its founding ancestor, a ritual leader, a ritual speaker and a clan house known as a korke or koke bale with an adjacent arena or nama, the location of the sacred nuba nara stone or stones that symbolise the founding ancestors. It is here that traditional ceremonies are conducted, some involving a sacrifice to the ancestors (kewokokeng) in the form of a male goat.

The big kampong of Lato has a large number of clans such as suku Angin, Dalu, Emar, Hayon, Hekin, Jawan, Kelore, Lewotobi, Manuk, Maran, Open, Soge (pron. Sogen), Talar, Teluma, Tukan and Watun. Twelve of these are endemic clans, but others are immigrant clans who have moved into the village from elsewhere, such as Teluma, Tukan, Lewotobi and Manuk, the latter believed to originate from the village of Lewoingu. The immigrant suku have a lower status that the endemic suku.

A new clan house or korke at Leworok

The clans are traditionally exogamous and arranged within an asymmetric circular system of alliance. Each individual clan has an alliance with one or more wife-giving clans, known as opulaké or more strictly belaké, and with one or more wife-taking clans, known as opubiné or simply opu. Wife-giving clans had a higher status than wife-taking clans. Because the system of marriage alliance was asymmetric, these two sets of clans had to be different – if clan B received the daughters of clan A it could not reciprocate by offering its daughters back to clan A since that would be symmetrical alliance. It had to supply wives to clan C.

In the past the norm was cross-cousin marriage - a young man was obliged to marry his mother’s brother’s daughter. Over time this eased, and a man was simply encouraged to marry into the clan or lineage of his mother. Today the rules are less rigid.

Marriage is secured through the exchange of gifts between the two clans forming the alliance, the wife-taking clan providing bridewealth or belis, ideally in the form of elephant tusks but increasingly today cash, and the wife-giving clan making a counter-prestation of primarily textiles. The tusks move in a circle around the clans in the village and the clan leaders try to ensure that wherever possible the tusks remain within the village.

For belis, each house has textiles and other items which they have inherited through marriage exchanges and they use these old adat textiles for belis today. They also supplement the belis with cash and goats. The more educated the woman, the higher the bride price. No bridewealth is necessary if a man marries a woman from outside the region.

One important element of Lamaholot culture in East Flores is the traditional system of leadership, where each village was governed by four ritual leaders (Vatter 1932, 81):

- the kepala Koten was the most senior of the four leaders, being in control of internal village affairs including land ownership,

- the kepala Kelen was responsible for external affairs, dealing with neighbouring villages and in the past dealing with the Dutch authorities,

- the kepala Hurit (also Hurin or Hurint ) and the kepala Marang were advisors and mediators if there was a disagreement between the heads of Koten and Kelen.

Other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders became too powerful. Since Independence and the introduction of democratic regional and village government in the early 1960s, their roles have been superseded by an elected kepala desa.

Today the four ritual leaders still play an important role during the ritual sacrifice of goats and pigs. The kepala Koten holds the animal’s head, the kepala Kelen holds the back legs, the kepala Hurit wields the knife while the kepala Marang is responsible for chanting ritual prayers. The animal’s blood is then spread on the village’s sacred nuba nara stone.

Many writers mistakenly interpret the four positions of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang as representing village patrilineal suku clans, but the latter are completely different. Traditionally the leaders of specific village sukus will have been assigned to the roles of head of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang. These will be different for every village. However in some villages the less important positions of Hurit and Marang are not represented.

In the main village of Lato, the role of Koten is taken by sukus Hayon, Watun, Open and Angi while that of Kelen is taken by suku Soge.

Each suku also has its own exclusive traditional ikat textile patterns, owned by that clan. Before marriage a girl will bind the pattern of her father’s clan, but after marriage she must bind that of her husband’s clan. A woman cannot bind or wear the pattern belonging to another clan without first obtaining that clan’s permission.

Return to Top

Titehena Weaving

The main centres of weaving in Titehena are the kampongs of Lato, Tenawahang, Tuakepa and Leworok. In most of these villages many weavers have come together in recent years to form self-help groups. The largest kampong of Lato has four kelompok, each with around 20 weavers, as well as some additional smaller groups. There are also weavers groups in Tuakepa and Leworok. The Leworok group was set up by Litfina Lito Kelen in 2011 in an attempt to revive the village’s weaving traditions. It is named Tapik Balik, meaning ‘return like before’, encouraging women who had given up weaving in the past to start again and to maintain the village’s weaving culture. Women had previously abandoned the craft because it was difficult and labour-intensive, especially using traditional materials. The group started with 9 weavers and in a few years this had increased to 15 weavers. The small village of Beloteba is Islamic and has no tradition of weaving.

In the past the majority of cotton used in this region was locally grown, hand-spun and naturally dyed. However today most weavers are using commercial yarn and colour it using synthetic dyes.

Tree cotton, Gossypium arboreum, growing in a garden in Titehena

Cotton thrives in this area. The weavers plant cotton seeds in their gardens outside the villages during the rice-planting season at the start of the rainy season around November and harvest the cotton in the early part of the dry season during May.

An old menalok gin in Titehena

The cotton bolls are dried in the sun and then deseeded using a menalok gin. After fluffing up the fibres with a menuhuk bow they are hand-spun using a wooden tenure drop spindle. In the big village of Lato, most of the elderly women still know how to drop-spin.

A woman drop-spinning at Lato, wearing a modern synthetically dyed kewatek méan.

In Titehena, as elsewhere in East Flores, the weavers traditionally dyed with indigo (tau) and morinda (keloré). However before preparing their natural dyes, they are first required to perform rituals to request permission from their ancestors.

Although morinda grows extensively around the rocky shorelines of Flores Island, it is less common in the east. However the weavers in Titehena report that morinda is easily found in the surounding forest. The roots are traditionally harvested at the height of the dry season, in August and September. On the other hand, candlenut (kemiri) for pre-oiling the yarns is plentiful throughout the forested hillsides.

Candlenut trees grow prolifically in the forests of Titehena

The bark and dried leaves of the aluminium-rich Symplocos mordant is obtained from trees that grow in the mountains nearby. The weavers refer to Symplocos as lour (pronounced ‘lure’). The morinda dyeing process that they use results in a very attractive rich and deep chestnut brown.

Morinda-dyed yarns in Titehena

In bridewealth cloths it is obligatory to dye the wider ikat bands with indigo followed by morinda. As a general rule all of the indigo is overdyed to produce a purplish-dark brown. This over-dyeing is called belapit. According to Ruth Barnes, it was said that no indigo blue should show in the finished cloth (1994, 174). However in Titehena, many of the finest bridewealth sarongs have fine blue detailing, often in the form of narrow indigo ikatted stripes. A few of the best have extensive indigo detailing in the main ikat bands.

Titehena weavers also use small amounts of kunyit to make yellow or orange stripes and turi leaf for green. They also make a brown tannin dye using kulit luar (literally ‘outer skin’), the outer bark from a big tree that grows in the mountains.

An ikat binding frame hung on the side of a house in Titehena

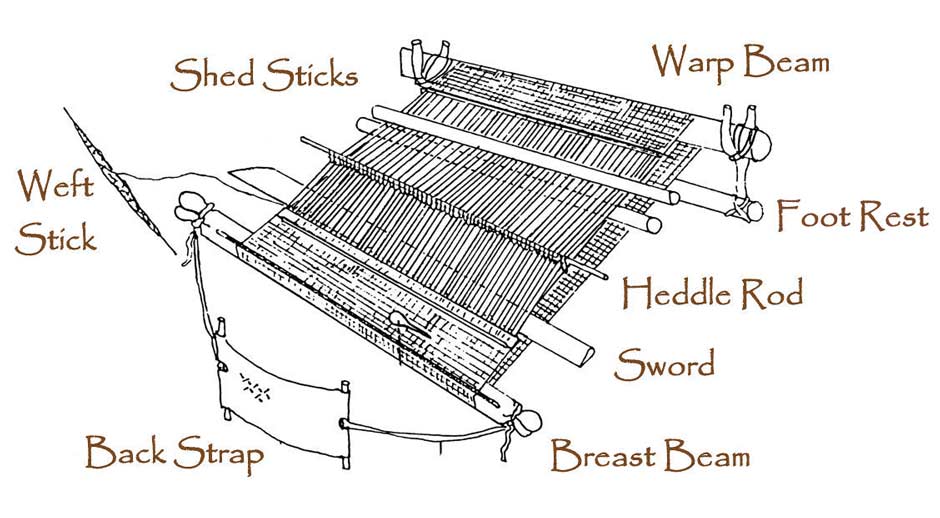

As elsewhere, weavers use the short Lamaholot body tension loom, weaving each panel of their two-panel sarongs separately.

The short Lamaholot body tension loom

In this region the kewatek méan are generally not decorated with split nassa shells, although there are one or two exceptions. This is interesting because the shells used by weavers in Demon Pagong are collected on the beach at Konga in Titehena.

Interestingly the village of Mudajaba in Sikka Regency has immigrants from Lato who still weave in the Lato manner.

Return to Top

Titehena Textiles

Even within the small district of Titehena there are modest differences in the textiles made in different villages, such as those between Lato and neighbouring Tenawahang.

Titehena textiles display a wide variety of motifs. Each clan has its own exclusive pattern, which is regarded as that clan’s intellectual property. It is not possible to copy another clan’s motifs without first obtaining that clan’s permission. The relationship between ikat band motifs and clans was first mentioned in the western literature by Maxwell in relation to the sarongs from the Demon Pagong region (1980, 149).

Before marriage a girl will only use the pattern of her father’s clan, but after marriage she must use the pattern of her husband’s clan. Local weavers explained to us that this can be difficult to learn and the mother-in-law can get angry if the young bride encounters problems. They not only had to cook for the family and maintain their new home, but quickly learn to bind the new family pattern.

In Leworok, for example, the motifs used on women’s ceremonial kewatek méan sarongs are based on the naga snake or dragon. The motif for suku Koten is the dragon’s head, that for suku Maran is the tail, while that for sukus Kelen and Hurit is the body. If a weaver wishes to incorporate more than one of these motifs in a single textile, women representing each of the four groups must first meet and perform a ritual seeking permission from the ancestors.

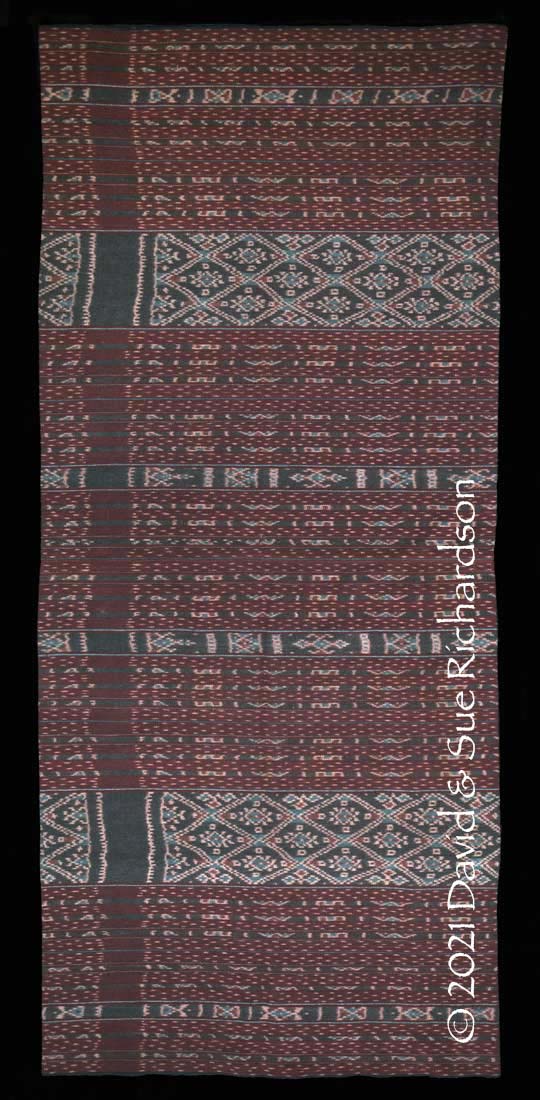

Titehena weavers produce two types of women’s tube skirt, which are made from two separately woven panels. In this region they are both referred to as kewatek. The kewatek mitén (black kewatek) is for everyday wear and is equivalent to the kewatek mowak or pasan made in other regions of East Flores. The kewatek méan (red kewatek) is traditionally used for adat ceremonies and bridewealth exchange, belis. For formal attire men and women also have a traditional embroidered blouse called a senuji.

An old senuji in the collection of the Museum Daerah Nusa Tenggara Timur, Kupang

Today these restrictions are less rigid and some mature women will use a kewatek méan as an everyday sarong.

Wearing a kewatek méan over the shoulder in Titehene

However most younger mothers and girls dress more casually in t-shirts and shorts or thin printed cotton sarongs.

A woman with her daughter in kampong Lato

Titehena men only have one type of hip wrapper, the senai mitén. They do not have an equivalent of the senai méan or nowing used in neighbouring Léwoléma.

In an attempt to maintain local textile traditions, the government of East Flores Regency introduced regulation number 49 in 2017 concerning the ‘clothing of the state civil administration’. This requires all government employees and teachers to dress in traditional regional costume on the first Monday of every month. However most of the textiles worn on that day are made from synthetically dyed commercial cotton.

Return to Top

Kewatek Mitén

The kewatek mitén is decorated with alternating narrow stripes of ikatted indigo and plain morinda, sometimes combined with plain stripes of undyed cotton. The nomenclature mitén, black, refers to the ikatted bands and stripes being dyed with only indigo. The ikatted stripes are only decorated with simple motifs such as chevrons, diamonds and squares. Some resemble the capital letters M or W. It is not necessary for such skirts to have an uncut rewok - the unwoven section when the cloth is removed from the loom.

A kewatek mitén belonging to a family in Lato

One encounters very few kewatek mitén in Titehena today compared to kewatek méan, suggesting that weavers stopped or significantly reduced making them some decades ago. It is probable that they were replaced by cheap printed cottons and batiks. A similar situation occurred in neighbouring Léwoléma, where women started weaving their own simple working clothes coloured with chemical dyes and devoid of ikat decoration (Graham 1994, 237).

Return to Top

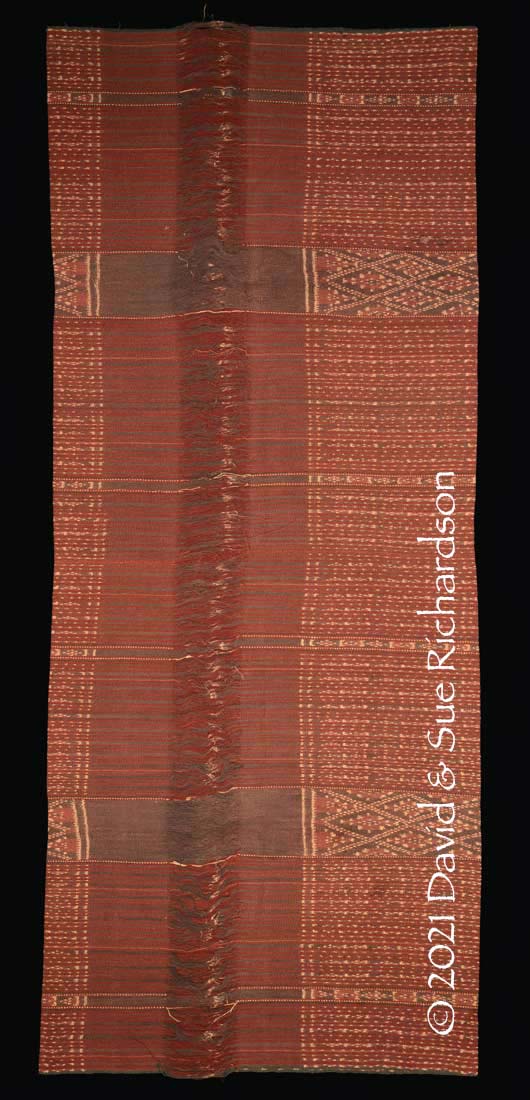

Kewatek Méan

The kewatek méan is decorated with bands and stripes of morinda-dyed ikat alternating with plain morinda stripes. Hence the designation méan or red. The weft is also always dyed with morinda.

To be used for bridewealth the kewatek méan must also be woven from hand-spun yarn and must have at least some of the indigo overdyed with morinda, a process known as belapit (Barnes 1994, 174). Usually the overdyeing is confined to the ikatted bands, not the simple dashed ikatted stripes.

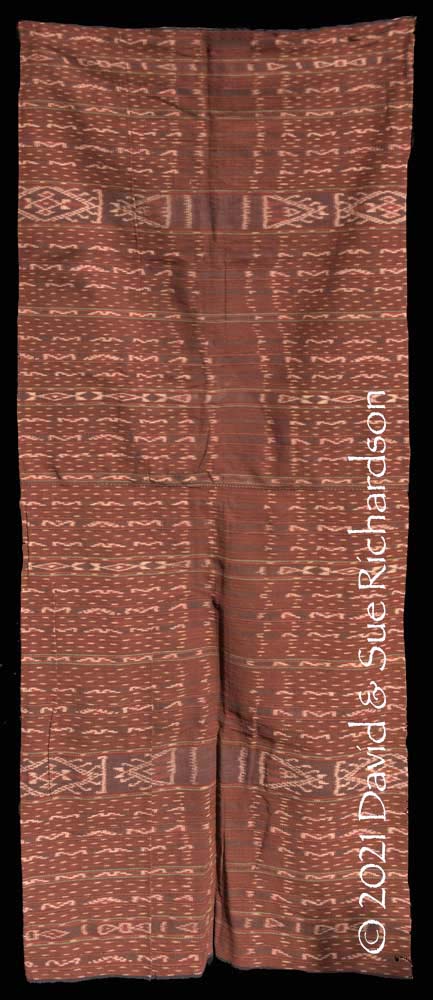

In the past it was also essential that the kewatek méan had uncut warps – the circular warp on which each panel has been woven must not have been cut to make a side seam. Instead the kewatek was formed from two panels containing a vertical section of unwoven warps, referred to in Titehena as the rewok. In recent decades this requirement has fallen into disuse and the rewok is removed so that the cut edges can be joined with a rolled seam.

When used in bridewealth exchange there was a standard relationship between the bridewealth or belis given by the clan of the groom in the form or one or more elephant tusks (bala) and the counter-prestation given by the clan of the bride in the form of textiles. In East Flores this tended to vary from region to region.

In Titehena there was a standard rate of exchange between bridewealth based upon an elephant tusk and the counter-prestation of kewatek méan sarongs:

- A bala meka is a long tusk measuring from fingertip to finger tip and is exchanged for seven kewatek méan.

- A bala lega is a shorter tusk measuring from fingertip to just beyond the centre of the chest and is exchanged for five kewatek méan.

- A bala ari is a small tusk, just one arm length long, and is equivalent to two kewatek méan. Such tusks are used to open the way for marriage negotiations.

Each panel of the kewatek méan is completely covered with bands and stripes and is devoid of the wide plain morinda terminal band found on the Lamaholot bridewealth sarongs of western Solor or Lembata. One of the ikat bands in each panel is generally much wider that the others and is known as the kenirék belén, the large pattern or motif (kenirék = pattern or tattoo, belén = large or important). There is at least one secondary band (often more) and then a large number of minor ikat bands, each separated from its neighbour by a band composed of clusters of simple dashed stripes. In the finest sarongs the latter tend to be narrow but in lower-status sarongs they can be quite wide.

Despite this standard arrangement of bands and stripes, it seems that in Titehena the design of almost every kewatek méan is different. It is impossible to find two the same or even closely similar.

The simplest have narrow kenirék belén composed of just fifteen kenuma or ikat bundles and a simple zigzag design. This lower-status pattern seems to represent the body of the naga dragon.

A simple kewatek méan owned by a woman in Lato

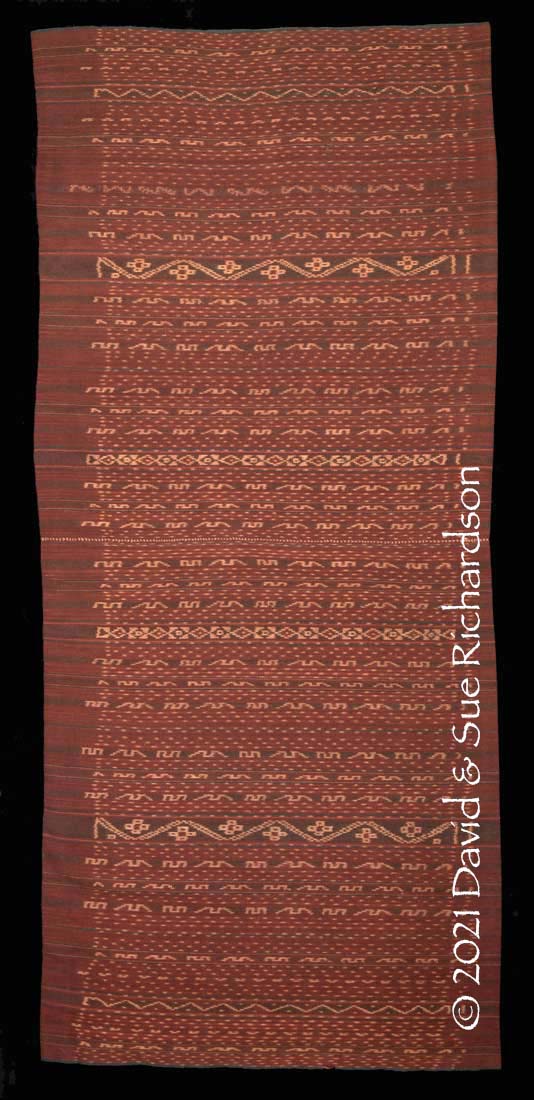

The second zigzag kewatek méan was woven in Tenawahang in the 1960s by Susanna Oreng Tukan from suku Tukan. She was born in Tenawahang in 1945 and sadly died of a stroke in 2015 when she was 80-years-old.

A kewatek méan woven by Susanna Oreng Tukan from Tenawahang. Richardson Collection

The simplest Lewolaga kewatek méan acquired by Ernst Vatter was decorated with multiple bands decorated with a wave-like meander (Barnes 2004, 132). However some caution is needed with this piece because Vatter recorded that he did not collect it in Lewolaga but in Balaweling on the northwest coast of Solor Island.

Some Titehena kewatek méan are decorated with geometric rectilinear motifs with angular hooks. For example, a kewatek méan woven by Odi Emar, from suku Emar, is decorated with an elongated eight-hooked cross and a hooked diamond enclosed by a cross. Both have blue indigo detailing. The latter motif is called kepati or kapati, the old wooden box with three compartments used for holding siri pinang betel chew or sometimes sewing tools. One unusual feature is that the ikat band contains a terminal row of tumpal motifs, which are rarely found in Titehena textiles.

Ibu Odi was born in the Titehena kampong of Lamika, close to Wolo on the main trans-Flores highway, and moved from Lamika to Lato to marry a local farmer when she was aged 25. She died in 1986, aged over 70 years old.

A kewatek méan woven around 1950 by Odi Emar from suku Emar in Lato and acquired from her daughter. Richardson Collection

Another kewatek méan with geometric motifs in Leworok

Some of the senior clans in Titehena decorated their ikat bands with hooked diamond motifs, which represent the head of the naga dragon. This motif is very similar to the sura aran pattern used by weavers in kampong Blepanawa in Demon Pagong.

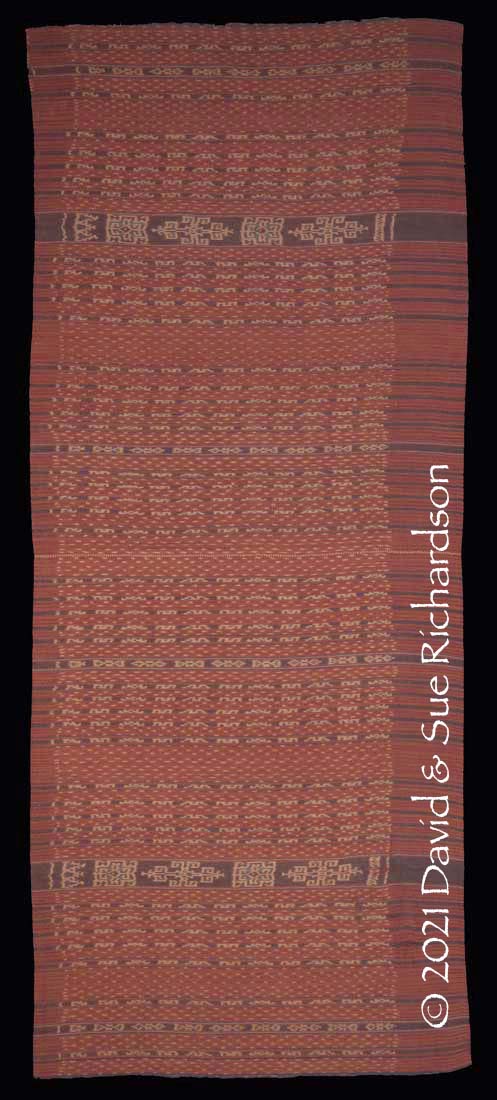

An elegant ceremonial kewatek méan from Leworok alternates a small hooked diamond motif with a geometric cross-shaped figure. All of the indigo has been overdyed, with the exception of a few narrow plain indigo warp stripes.

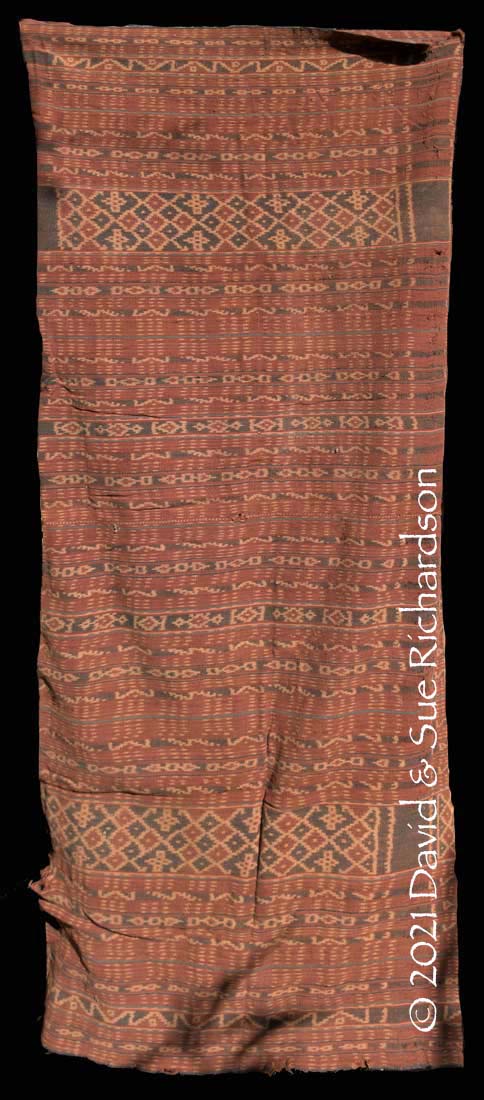

A kewatek méan woven in Leworok. The circular warps have been cut and hand sewn into a tubeskirt with a rolled side seam. Richardson Collection

A second kewatek méan from Leworok has much larger hooked diamond motifs alternating with vertical columns of diamonds. Note how the half hooked diamond motif resembles the head of the mythical dragon.

The top section of a badly damaged kewatek méan woven in Leworok

A very fine kewatek méan in our collection has a similar arrangement of motifs. It was woven by Uto Soge from suku Soge in Lato, around 75 years ago. Uto began weaving when she was a teenager. According to her granddaughter it was used as part of the counter-prestation for the marriage of Uto Soge’s daughter, Elis Soge, the granddaughter’s mother. Uto Soge died in 2002, when she was over 80 years old.

A kewatek méan woven by Uto Soge from suku Soge, Lato. Note the crude repair. Richardson Collection

In some kewatek méan the hooked diamond motif appears alone, in others it alternates with a geometric motif.

Ernst Vatter acquired a fine example of this style when he travelled on the Flores-Way through Leworok in January 1929. He classified it as an odo pito type, meaning to ‘push seven’ – each ikat bundle was composed of seven spun yarns. It was considered the most valuable type of bridewealth sarong, which was only worn for major celebrations.

The finest of the three ‘kewatek méã‘ acquired by Vatter in Leworok in 1929

Above and below: two kewatek méan owned by families in Lato

The example below is unusual for Titehena, having being embellished with split nassa shells

Another privately owned kewatek méan from Lato

In some kewatek méan the hooked diamond motifs are arranged in a continuous row with the ends touching or interlinked.

A damaged kewatek méan with a row of large hooked diamonds belonging to a weaver in Lato

A fine kewatek méan woven around 1960 by Yofina Maran from suku Maran in Lato. She was born in Lato and married there. She died in 2018 aged over 80. Richardson Collection

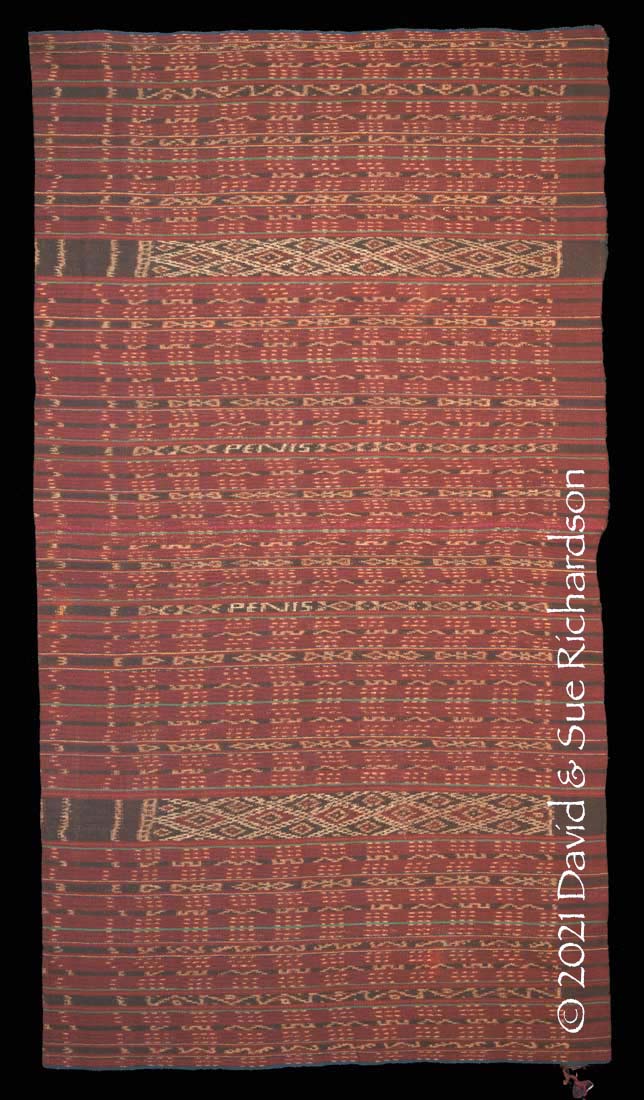

Some of the finest Titehena sarongs are decorated with the snakeskin pattern. According to local weavers, the pattern comes from a local fairy tale about a girl from kampong Kroko Pukang who fell in love with a big snake. In her dreams the snake told her to weave a snakeskin pattern. So that she could bind the pattern of the snake’s skin, the snake came and lay beside her.

Kroko Pukang is the local Lamaholot name for the twin islands of Lepan Batan located between Lembata and Pantar, believed to be the home of the ancestors of many of the Lamaholot residents of East Flores. When it was inundated by a tsunami, possibly in around 1525, the survivors fled by sea, seeking refuge on Pantar, Lembata, Solor, Adonara and East Flores.

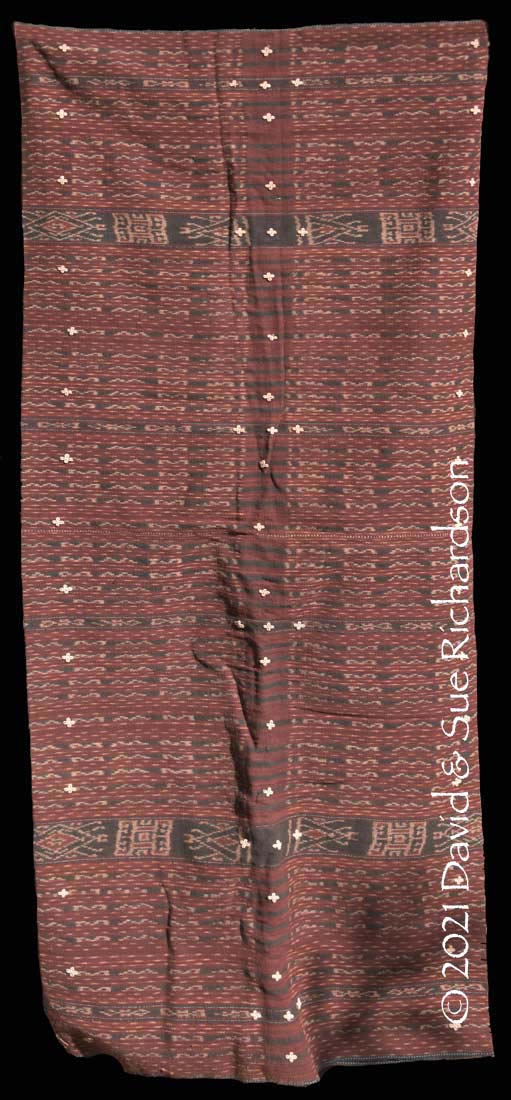

The snakeskin kewatek méan below was woven in Lato in 1985 by Theresia Layu Teluma, a weaver belonging to suku Teluma who was born in Tuakepa in 1955 and, at the age of 22, moved to Lato to get married. It has been naturally dyed with indigo, morinda, kunyit and turi leaf and has an intact rewok. It was made with the intention that it would be used for belis although it has never been used as such. Each panel contains a narrow band of ikat inscribed with the initials PENIS, a dedication to Theresia Layu Teluma’s mother, Paulina PENI Soge.

A kewatek méan woven by Theresia Layu Teluma from Tuakepa. Richardson Collection

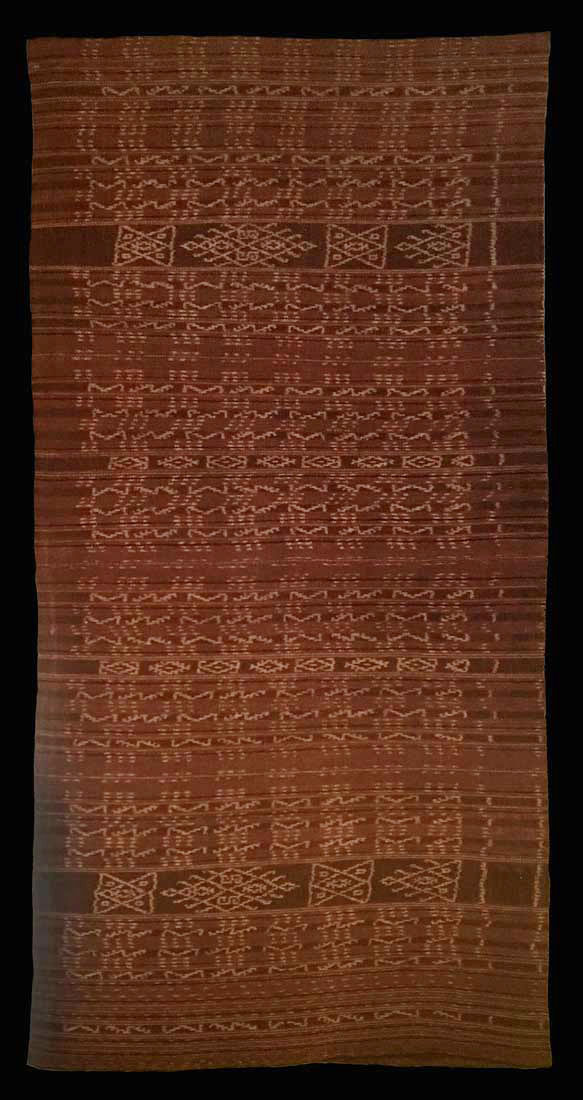

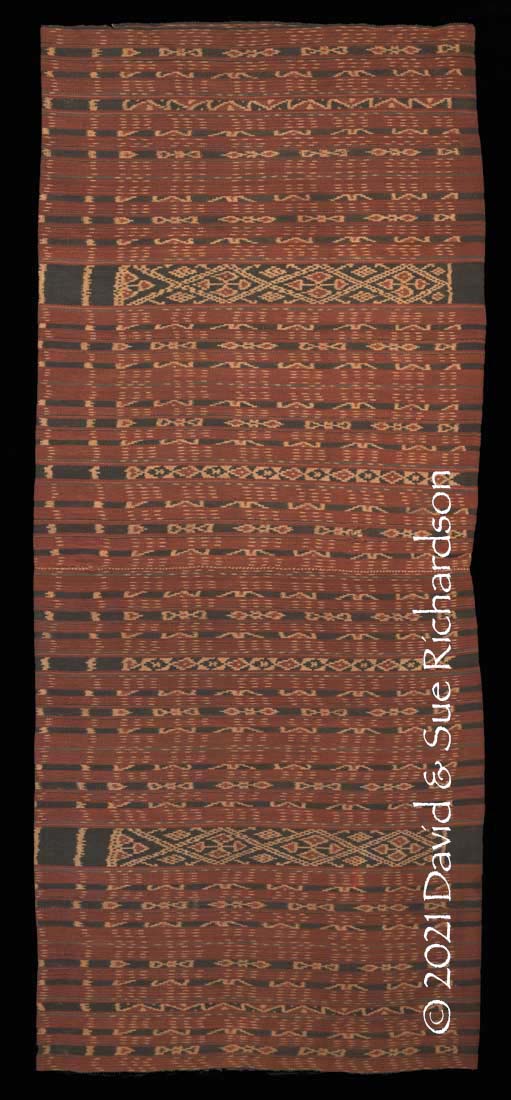

The next snakeskin kewatek méan was woven in Titehena around 1930. Unfortunately the name of the weaver has been forgotten. Previously used as bridewealth, it still retains its complete uncut rewok. The major decorative ikat band, the kenirék bélén (‘motif large’) is composed of 49 separate ikat elements or kenuma.

Above and below: A snakeskin kewatek méan woven in Titehena around 1930. Richardson Collection

One of the finest Titehena sarongs decorated with the snakeskin pattern has been woven with its major decorative ikat band, the kenirék bélén, assembled from 51 separate ikat elements or kenuma. It includes a significant amount of indigo detailing. It was woven in the 1960s by the late Yacoba Wata Talar from Lato who belonged to suku Talar. She sadly died in 2018.

A magnificent kewatek méan woven in the 1960s by the late Yacoba Wata Talar from Lato. Richardson Collection

It is clear that during the past century the weaving villages of Titehena have reached a high degree of excellence in their ability to bind and dye their prestige ikat textiles. The pressures of modernity now mean that those traditions are now rapidly eroding as young mothers no longer have the patience to weave or alternatively switch to producing their sarongs more rapidly using commercial yarn and synthetic dyes.

Return to Top

Senai Mitén

Local weavers in Titehena insisted that they had no equivalent to the men’s ikatted sarongs found elsewhere on mainland East Flores, namely the senai méan and the nowing. However it is possible there was such a sarong in the past – it has been claimed that the motif once used for Leworok men’s sarongs was based on the musang or Asian palm civet (Sen and Mari 2014).

A wedding ceremony in desa Watowara in 2017

(Image courtesy of Cendana News)

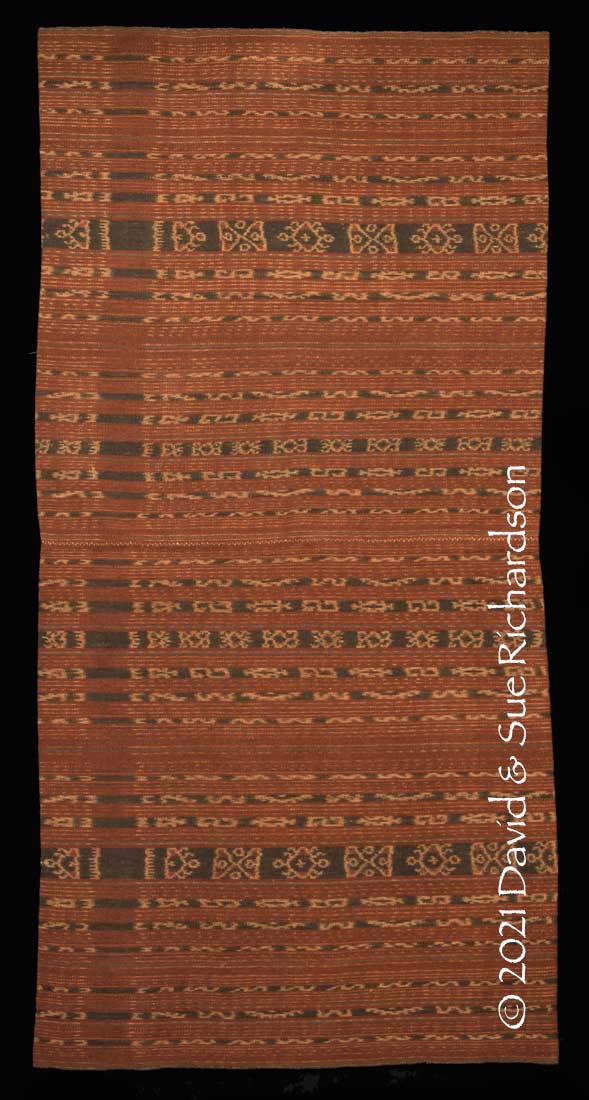

Today the only men’s ceremonial hip wrapper is the simple two-panel blue and black warp-striped senai mitén. Now it is only worn for adat and other formal ceremonies, such as a wedding or the Easter celebrations. However it is nothing more than an item of clothing and plays no part in the gift exchange related to marriage.

Several decades previously the indigo-dyed senai mitén was decorated with simple checks. It was very similar to the nofi still woven in Lamalera today.

A man’s senai mitén sarong from Titehena

The western Lamaholot term senai refers here to a man’s two-panel hip wrapper. Jasper and Pirngadie suggested that senai was the Larantuka term for a man’s sarong and the Solorese term for a selendang (1912, 276). However the linguist Keraf suggest the term has the same meaning in Solor Lamaholot (Keraf 2016, 49). Keraf suggests it is related to the verb sai – to tear a cloth or fabric (2016, 268).

The same term is also used across eastern Indonesia to describe a single panel shawl or shoulder cloth – from the Endenese and the Lio of Ndona in Ende Regency, to Adonara and Lamalera on Lembata (Al Khatab 2011; Barnes 1984, 109; Barnes 1989, 49).

Return to Top

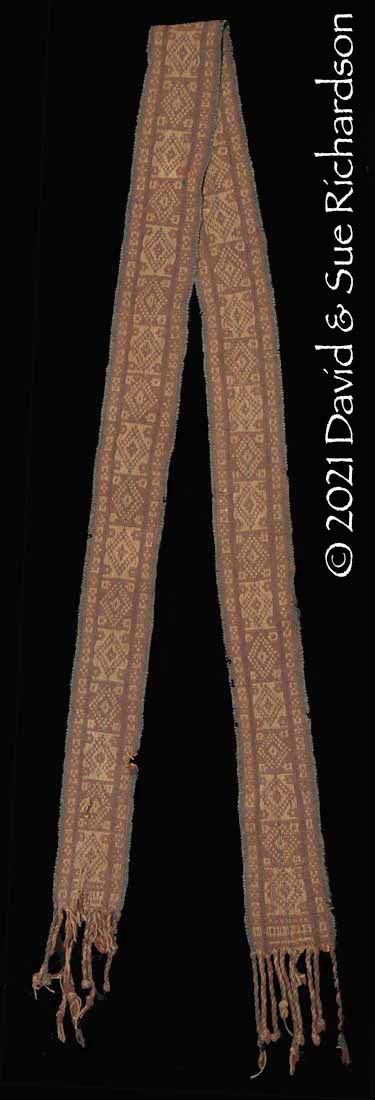

The Mét Belt

In the past some Titehena weavers made men’s belts using the supplementary warp technique. These are known as mét. On Solor these narrow belts are called uwé. The technique seems to have been lost in Titehena, although it just about survives in a simpler form in Léwoléma.

The narrow belt below was woven in Leworok using hand-spun cotton yarn. The ground warps and wefts are singles that have been dyed with morinda, apart from the indigo-dyed warps for the selvedges. This has been decorated with a coarser plied, undyed supplementary warp. The pattern is a repetitive row of double diamonds flanked by simpler side borders. The warp ends have then been twisted and knotted to make a fringe, one end of which has been damaged through use.

A very old and narrow mét belt, woven in Leworok

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the weavers of Lato and Leworok for their help and patience in assisting us with our research. Many thanks also to our Lamaholot guide and friend Tony Labuan and our local driver Oskar.

Interviewing local weavers in Titehena

Return to Top

Bibliography

Andaya, Leonard Y., 2010. The ‘informal Portuguese empire’ and the Topasses in the Solor archipelago and Timor in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 391-420.

Angin, Ignasius Suban, and Sunimbar, Sunimbar, 2020. Kearifan Lokal Masyarakat Dalam Menjaga Kelestarian Hutan Dan Mengelola Mata Air Di Desa Watowara, Kecamatan Titehena Kabupaten Flores Timur Nusa Tenggara Timur

Aritonang, Jan Sihar, and Steenbrink, Karel, 2008. A History of Christianity in Indonesia, Brill, Leiden.

Arndt, Paul, 1940. Soziale Verhältnisse auf Ost-Flores, Adonare und Solor, Aschendorffschen Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster i. W.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2018. Kecamatan Titehena Dalam Angka 2018, Larantuka.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. East Flores Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden: textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, Hamilton, Roy W., (ed.), pp. 171-191, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 2004. Ostindonesien im 20. Jahrhundert: Auf den Spuren der Sammlung Ernst Vatter, Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt.

Barnes, Robert H., 2009. A temple, a mission, and a war: Jesuit missionaries and local culture in East Flores in the nineteenth century, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 165, no. 1, pp. 32-61.

Barnes, Robert H., 2010. Raja Servus of Larantuka, Flores, Eastern Indonesia, Moussons, vol. 16, pp. 39-56.

Daus, Ronald, 1989. Portuguese Eurasian Communities in Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Graham, Penelope, 1994. Vouchsafing Fecundity in Eastern Flores, Gift of the Cotton Maiden: textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, Hamilton, Roy W., (ed.), pp. 229–245, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Hägerdal, Hans, 2012. Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea: Conflict and adaptation in early colonial Timor, 1600-1800, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2013. Profil Daerah Flores Timur, Kabupaten Flores Timur, Larantuka.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/lama1277-ileap

Kleian, E. F., 1891. Eene voetreis over het oostelijk deel van het Eiland Flores, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 34, pp. 485-532.

Maxwell, Robyn J., 1980. Textile and Ethnic Configurations in Flores and the Solor Archipelago, Indonesian Textiles: Irene Emery Roundtable on Museum Textiles, 1979 Proceedings, pp. 141-154, The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.

Maxwell, Robyn J., 1981. Textiles and Tusks: Some Observations on the Social Dimensions of Weaving in East Flores, Five Essays on the Indonesian Arts, pp. 43-61, Monash University, Melbourne.

Pemerintah Desa Watowara, 2018. Profil Desa Watowara, Kecamatan Titehena, Lato: Pemerintah Desa Watowara

Sen, Wenseslau, and Mari, Yulius Fanus, 2014. Budaya menenun dapat membangkitkan kembali semangat perempuan untuk Mandiri, Ende untuk Indonesia, http://ende-bergerak.blogspot.com/2014/03/

Steenbrink, Karel A., 2003. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1900, KITLV Press, Amsterdam.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Viola, Maria Alice Marques, 2013. Presença histórica “portuguesa” em Larantuka (séculos XVI e XVII) e suas implicações na contemporaneidade, PhD Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 5 January 2021.