Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Women’s Sarongs

Lawo with Centre Panels

Lawo with Vertical Bands

Lawo with Horizontal Bands

Lawo with a Complete Covering of Motifs

Lawo Butu

Men's Textiles

Luka Sarongs

Luka Shoulder Cloths

Bibliography

Weaving in Ende Regency

Historical References to Endenese and Lio Textiles

Samuel Roos 1877

Herman ten Kate 1891

Max Weber 1899-1900

Johannes Elbert 1912

Charles Le Roux 1915-1919

Bertho van Suchtelen 1921

Elisabeth Wilhelmina Viruly Verbrugge 1922

Father Simon Buis SVD 1923

Raymond Kennedy 1949-1950

Roy Hamilton 1989

Willemijn de Jong 1987-2022

Conclusions

The Nggela Weaving Community

Nggela Ecology

Local Cotton and its Preparation

Commercial Cotton and Synthetic Yarns

Warping Up and Binding

Indigo Dyeing

Morinda Dyeing

Other Natural Dyes

Synthetic Dyes

Unbinding and Starching

Assembling and Focussing

Final Starching

Weaving in Nggela

Loom Terminology

Sewing Up the Sarong

The Complete Weaving Process

Women's Sarongs

In line with the rest of the Lio ethnic region, an Nggela sarong is called a lawo, pronounced ‘lavo’. The same term is used in neighbouring Ngada and in Kodi in West Sumba. The Endenese call a sarong a rhawo (McDonnell 2009, 207).

Weavers performing a welcome dance in Nggela

Virtually all Nggela women's ikat sarongs have three panels – one central panel called the oné and two outer panels called the gha'i. However, there are rare exceptions. Only one type of sarong always has two panels – the highest status striped and beaded lawo butu, which is totally devoid of ikat. A panel is known as a nai, while a patterned ikat band is called a foko, meaning neck.

Generically a sarong that is dyed only with indigo is known as a lawo nggili, while one dyed with morinda, or indigo and morinda, is called a lawo kembo.

A three-panel cloth is structurally described as a lawo nai telu, telu meaning three, while a lawo nai rua has just two panels. A few lawo, especially in the adjacent Mbuli Valley but not in Nggela, are made with four panels, the two narrow middle panels carrying the central field design. These are called lawo nai sutu.

Lawo are often described in relation to their dominant ikat motif. Thus, a lawo redu has a centre panel decorated with the redu motif while a lawo pundi has a centre panel decorated with the pundi motif.

Lawo can also be classified according to their layout. Following her discussions with local weavers, in 1994 Willemijn de Jong composed a list of Nggela sarongs according to type that had been made and used in Nggela during the 1970s (1994a, 215). She identified twenty-one different sarongs, recognising that it was possible there might have even been more. She classified most of them into three separate categories:

The three main types of lawo sarong

| With centre fields | With vertical sections | With horizontal bands | |

| 1 | lawo redu | lawo jara élo | lawo népa nua or mité |

| 2 | lawo luka sémba | lawo pundi | lawo népa ndu’a |

| 3 | lawo wenda jara | lawo kapa lo’o | lawo mogha |

| 4 | lawo barai | lawo jinga runu | lawo gami tere esa |

| 5 | lawo kapa ria | lawo rangka or kanga au | lawo mangga lo’o |

| 6 | lawo kéli mara té’a | lawo lima desa | lawo gelo |

| 7 | lawo kéli mara mité |

In addition, there was a fourth type that was unstructured and completely covered with motifs (the lawo gamba), and a fifth type devoid of ikat (the beaded lawo butu).

Of the twenty-one ikat sarongs that de Jong listed in 1994, she noted that two - the lawo barai and the lawo kapa lo’o - were no longer made at that time.

Note that in the Lio language, ria means large, lo’o means small, mité means black, té‘a means yellow or light, jara means horse, kapa means boat, kéli means mountain, and gamba means picture.

It was taboo for younger women to produce and wear certain privileged designs, because it was believed that if they did they might become barren or die at an early age. Only post-menopausal women were allowed to tie the designs of the lawo luka, lawo mogha and lawo élo, as well as the man’s luka sémba shoulder cloth.

In life cycle rituals, particularity weddings and funerals, lawo redu, luka sémba and luka ria are the most important ritual cloths. They are initially bestowed on the parents of the groom by the bride's family. The lawo redu was also traditionally worn by the bride during the wedding ceremony.

Prior to 1945, Willemijn de Jong believes that the number of types of ikat sarongs was limited to six, some with horizontal stripes and some with central field patterns (de Jong 2020b, 2). At that time most women owned only two ceremonial sarongs, one for church and one for village ceremonies. The increasing availability of commercial machine-spun yarn in the 1960s, followed by the introduction of synthetic dyes in the mid-1970s, made it far easier and faster to produce an ikat sarong and encouraged the development of an increasing number of new ikat designs (de Jong 2020a, 25). By 1988 many women owned up to ten woven sarongs (de Jong 2020b, 2). Thanks to the imagination and creativity of local weavers, today there are even more types of ikat sarong. One of the latest designs is the lawo jaba muku also called the lawo batik, decorated all over with slices of banana (de Jong 2020b).

Traditional Nggela sarongs lack the two plain black bands that are found in Endenese sarongs, which are known as the mité méré. However these do appear in some Nggela sarongs and it is assumed that their designs have been borrowed from the Endenese. In Nggela these plain black bands are called the pake mité.

Another distinguishing feature of some Nggela sarongs is that following some, or all of the indigo immersions, small parts of the indigo-dyed bundles are re-bound to prevent them being overdyed with morinda. This means that the finished cloth is left with small blue highlights.

Some of the finest Nggela sarongs are woven with the outer terminal selvedges of the outer panels finished with an edging woven in alternating complementary warp. This is called bue mola. It is achieved by having a narrow section of alternating warps in contrasting colours

Return to Top

Lawo with Centre Panels

Lawo with a centre panel decorated with a lattice of motifs are the most highly valued Nggela sarongs, especially those with a red-brown ground. In some designs the centre field pattern spills over into the outer panels. Because of their high status, many of these are still made with the ikatted yarns dyed with morinda.

It is often stated that the centre field patterns found on this group of lawo have been inspired by the double ikat patola, imported into eastern Indonesia as prestige textiles for local elites. However, for many examples this assumption might be presumptive as we will discuss in more detail below.

Lawo Redu

The lawo redu is one of the highest status ritual sarongs woven in Nggela, prized as a bridewealth cloth and used in marriage and death ceremonies. It is ranked on a par with the men’s luka sémba shoulder cloth and the men’s luka ria sarong.

They were once important as gifts, and for wearing at weddings. In the past lawo redu were given as a bridewealth cloth by the bride’s family to the mother of the groom as part of the marriage exchange of goods (de Jong 1994a, 176). In addition, it was traditional for the bride to be given a lawo redu as a wedding dress from her mother's brothers. Today this no longer applies and brides can wear any high status ikat sarong, or even a Western bridal gown (de Jong 1994b, 178).

When Willemijn de Jong first visited Nggela in the 1980s she found that the lawo redu was worn regularly, especially by the older women. Later the design went out of fashion and was hardly worn at all, although there has been a revival among younger weavers during the 2010s (Wyss-Giacosa 2016, 72).

Mama Rosa Dalima Sina (left), the secretary of the Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kaipere Lesu Usu weaving group, wearing a synthetically dyed lawo redu. The head of cooperative, Mama Teresia Sarah, is in middle while the accountant, Regina Galle, is on the right.

In the past, the lawo redu were dyed with only a little red, so the older examples tended to have a dark background (de Jong 1994, 216).

Many include a wide band of ikat in the outer panels decorated with a row of hexagonal gha’i mité motifs with an eight-armed spider-like figure. This is somewhat similar to the chhabdi bhat 'flower basket' pattern found on a common type of Gujarati patola. This gha’i mité band seems to have been a later addition to the original pattern (de Jong 1994, 274).

The first example from the Richardson Collection was woven at some time between 1920 and 1950 in Nggela by the late Mama Teresia Rumi, who belonged to the highest status house of Sa’o Labo. She was still weaving at the age of 70, and was over 80 when she died, probably around 1982. The lawo redu was acquired from her granddaughter.

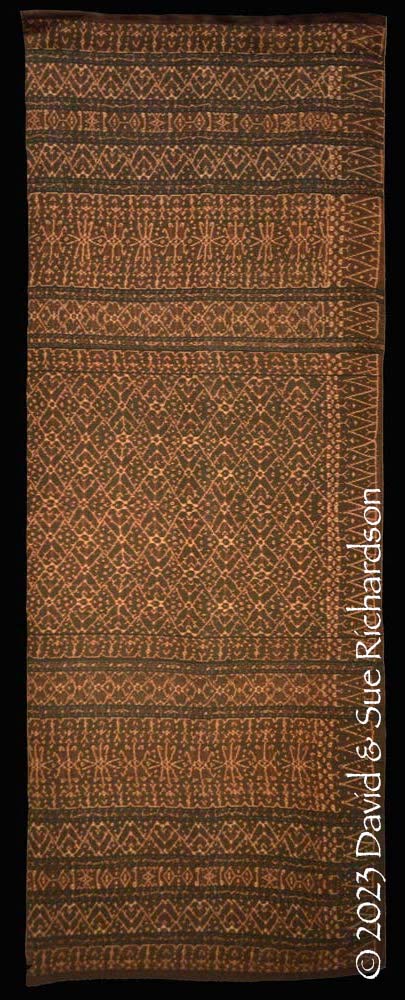

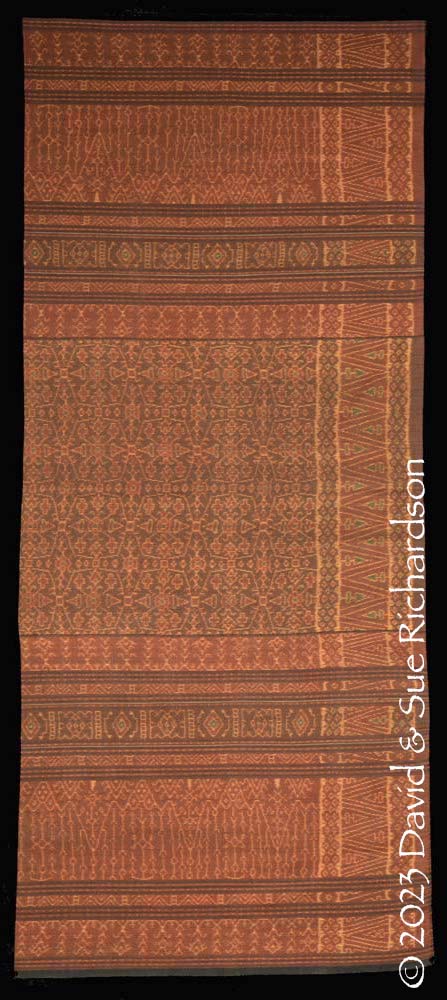

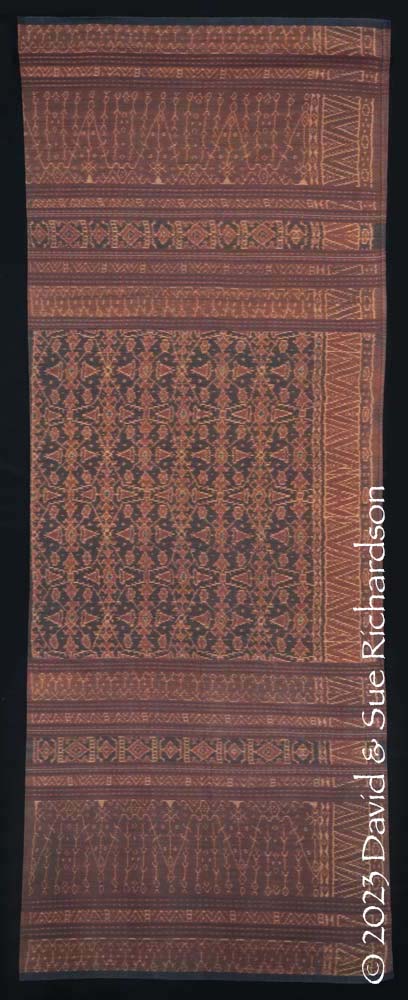

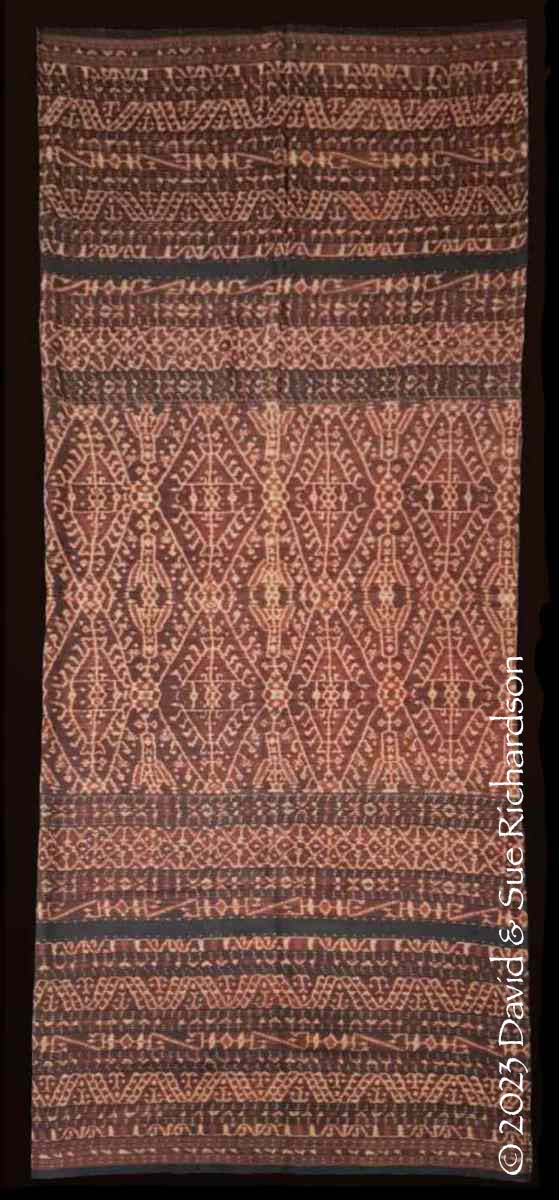

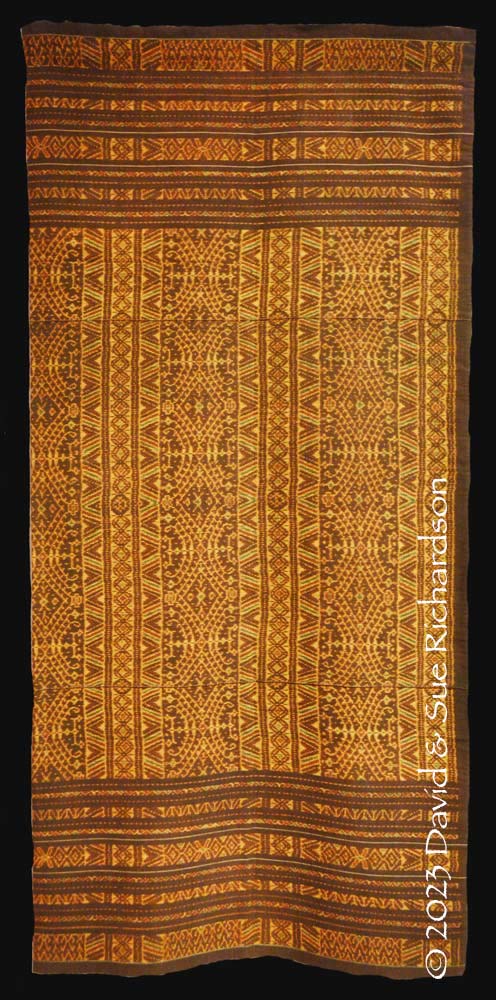

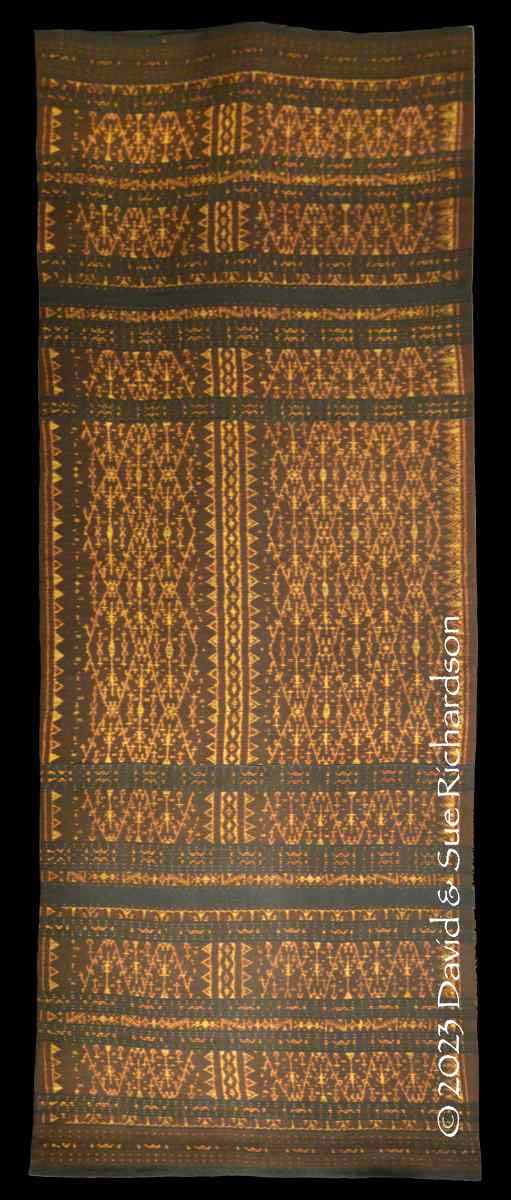

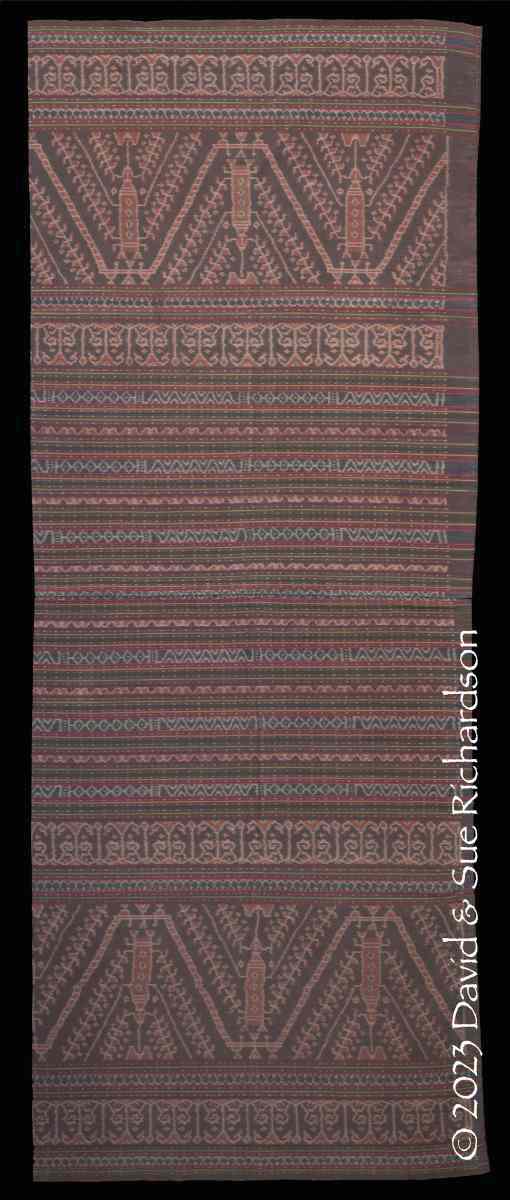

Lawo redu woven by Teresia Rumi. Length 180cm, width 69cm. Richardson Collection

The gha’i end panels have been decorated with an assortment of ikat bands ranging in width from very narrow to the 14cm-wide band of gha’i mité motifs. One band is decorated with small redu motifs, while two more have rows of half redu motifs.

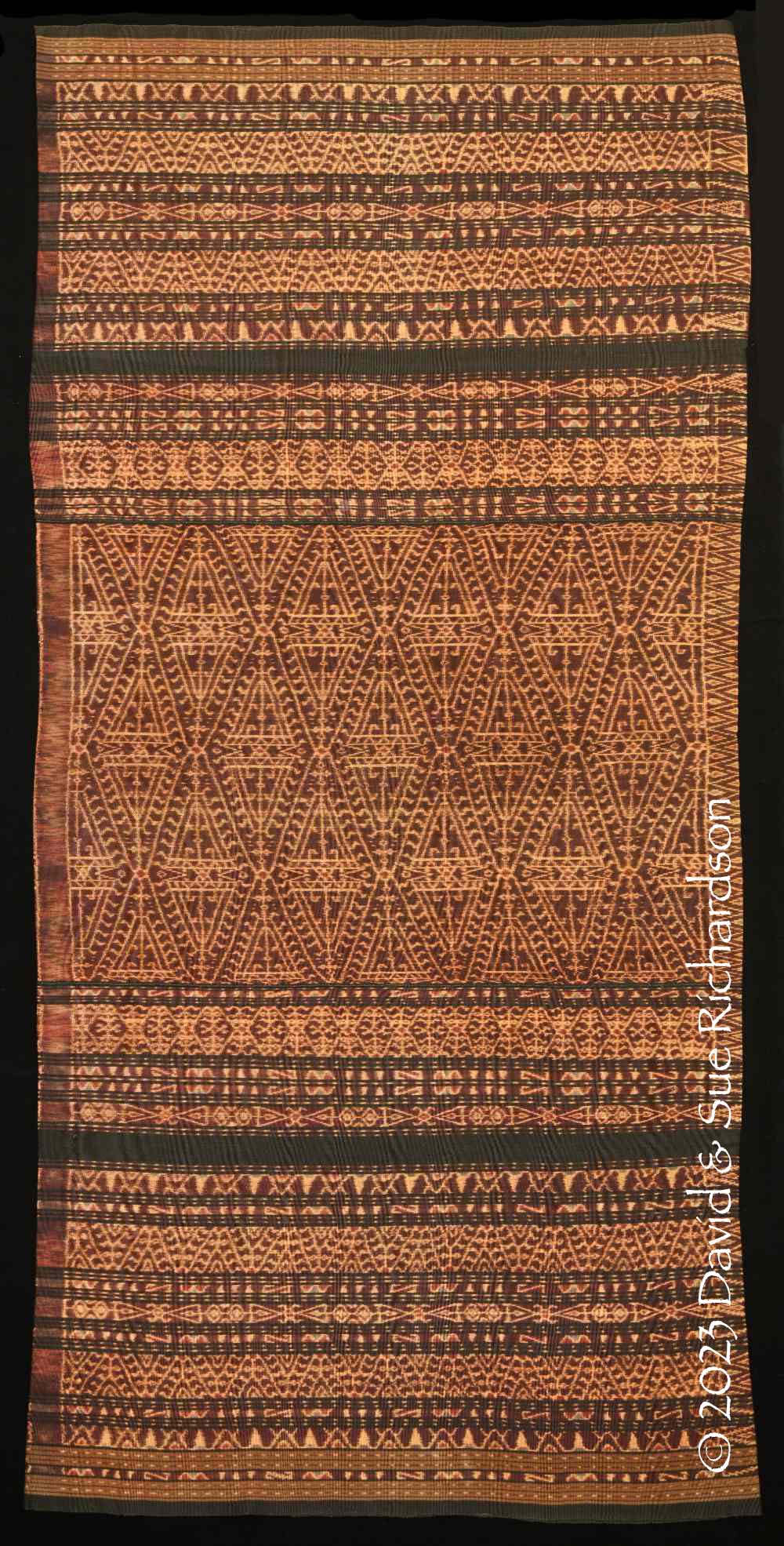

The second example was woven in Nggela around 1953 by the late Mama Agnes Ne from Sa’o Tana Tombu, located in the south zone of Bhisu Embulaka. She made it when she was about 30 years old. The morinda has been overdyed to produce the dark brown finish. It was acquired from her granddaughter.

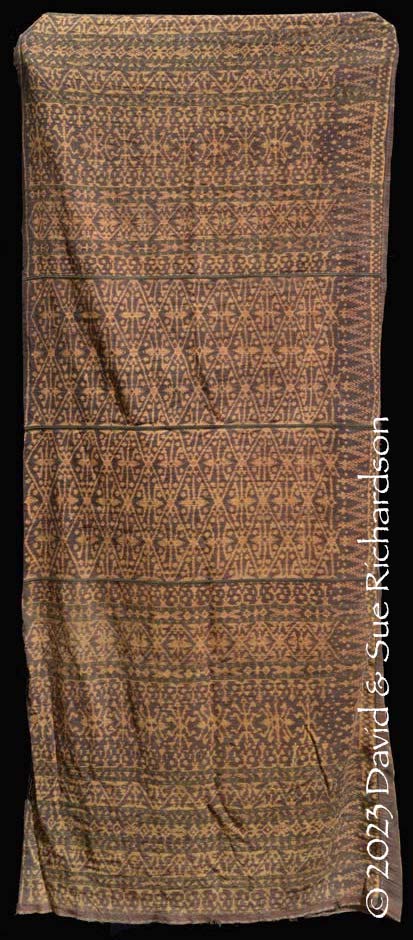

Lawo redu woven by Agnes Ne. Size 208cm by 66cm. Richardson Collection.

The third example was woven in Nggela more recently in 2008 by Mama Elisabeth Linda from Sa’o Siga Bata, who was born in the late 1940s. It was acquired from her daughter-in-law. It is coloured a deep red-brown, typical of later lawo redu sarongs.

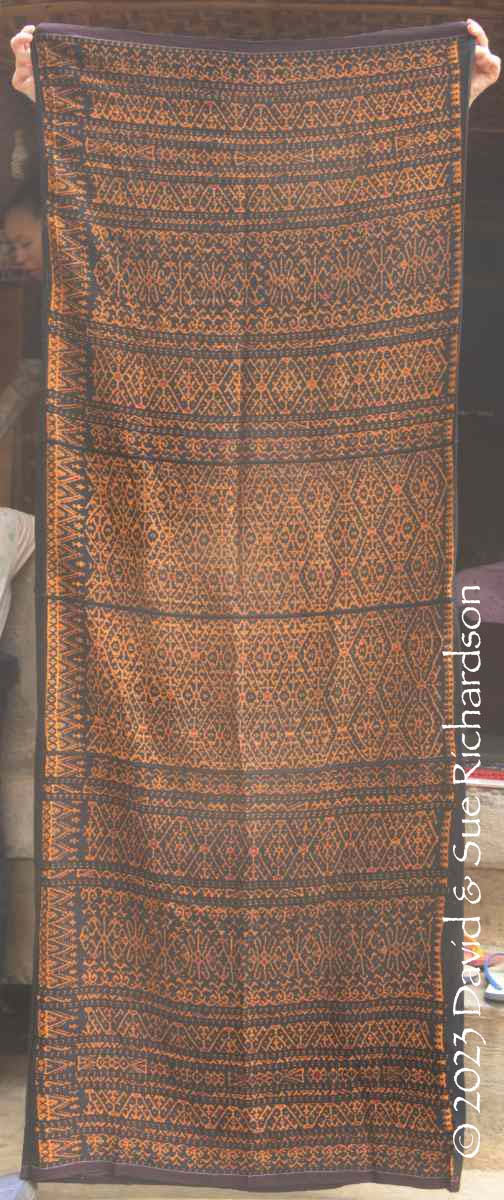

A lawo redu woven by Elisabeth Linda. Size 195cm by 68cm. Richardson Collection.

The next later example was woven in Nggela between 2000 and 2010, by Regina Galle, the accountant of the local weaving group Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kaipere Lesu Usu.

A lawo redu made by Regina Galle. Size 186cm by 62cm. Richardson Collection.

The gha’i end panels have multiple bands of ikat divided from each other by clusters of narrow black warp stripes, the widest band containing a single row of gha’i mité motifs and two outer bands repeating a lateral section from the central field.

Mama Regina naturally dyed the bound yarns with indigo followed by morinda, over-binding small sections of the indigo dyed yarns so that small highlights of blue appear as details within the pattern.

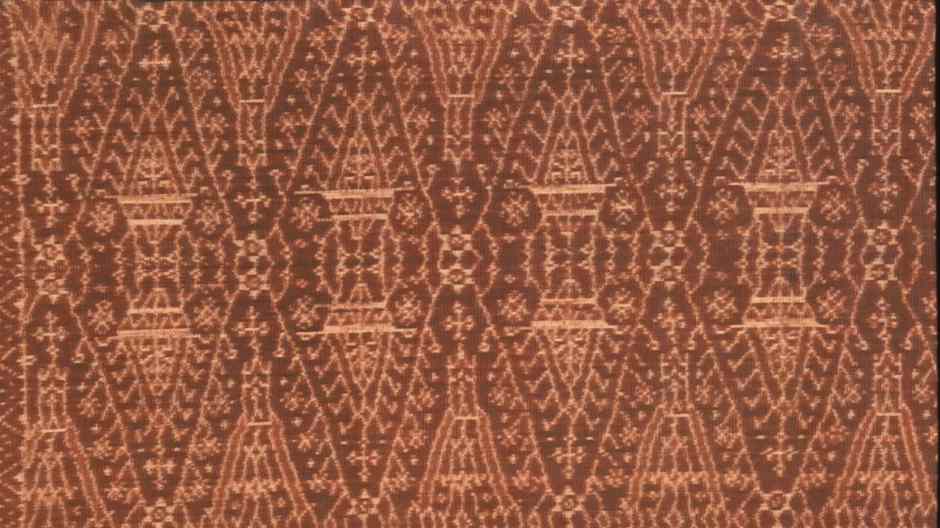

The rhombic redu motifs with some of the indigo uncovered and some overdyed with morinda

The fifth example was woven in Nggela in the 1960s by the late Mama Monica, and was acquired from her granddaughter.

A lawo redu kembo woven by the late Mama Monica in the 1960s. Size 176cm by 68cm. Richardson Collection.

A elderly woman dressed in her old lawo redu in Nggela

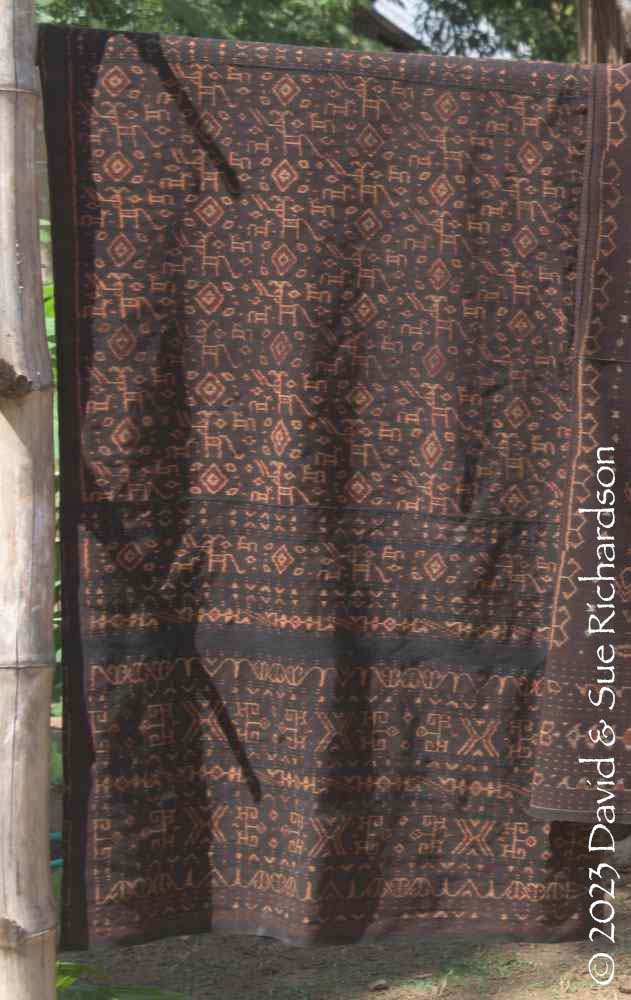

A modern chemically dyed lawo redu hanging out to dry in Nggela

There are various sub-types and variations of the lawo redu, some quite complex. For example, the lawo redu tara with the diamond-shaped redu pattern, the suffix tara meaning branching. It was made during the period 1967-1974 from a mixture of machine and hand-spun cotton dyed with indigo and morinda. Antonia Mbei (Nona Mei) wove the cloth, but her mother dyed the ikatted yarns. Nona Mei wore a second identical sarong for her wedding.

A lawo redu tara woven by Maria Antonia Mbei, Teresia Sina and Anastasia Bhoa between 1967 and 1974. De Jong Collection.

An identical type of lawo redu is produced by the Muslim weavers living in the nearby Mbuli Valley as far north as kampong Wolojita. Here they are known as lawo daki nggera rather than lawo redu. De Jong refers to them as a lawo daki (de Jong 1984, 218). They are assembled from four panels; the centre field being spread across two narrow panels.

The following new lawo daki nggera was woven in the kampong of Aemboi, close to the mouth of the Mbuli River. We observed a similar four-panel lawo daki nggera in Wolowaru.

A modern lawo daki nggera woven in Aemboi

The second example of a four-panel chemically dyed lawo daki nggera was woven in kampong Wato Rajo in the Mbuli Valey:

A lawo daki nggera displayed in Wato Rajo

Return to Top

Lawo Barai

Lawo barai incorporate the barai motif (pronounced ‘bray’), a smaller version of the rhombic redu motif. It is claimed that the design originated in the coastal district of Barai, which is 5km due west of Old Ende City in Kecamatan Ende Utara. The Endenese origins are evident from the paké mité plain black bands in the border panels, and the division of the pattern into three vertical sections - just like the zawo zombo wutu.

Lawo barai are considered out of fashion today, and de Jong found that by 1994 they were no longer being produced (de Jong 1994, 225).

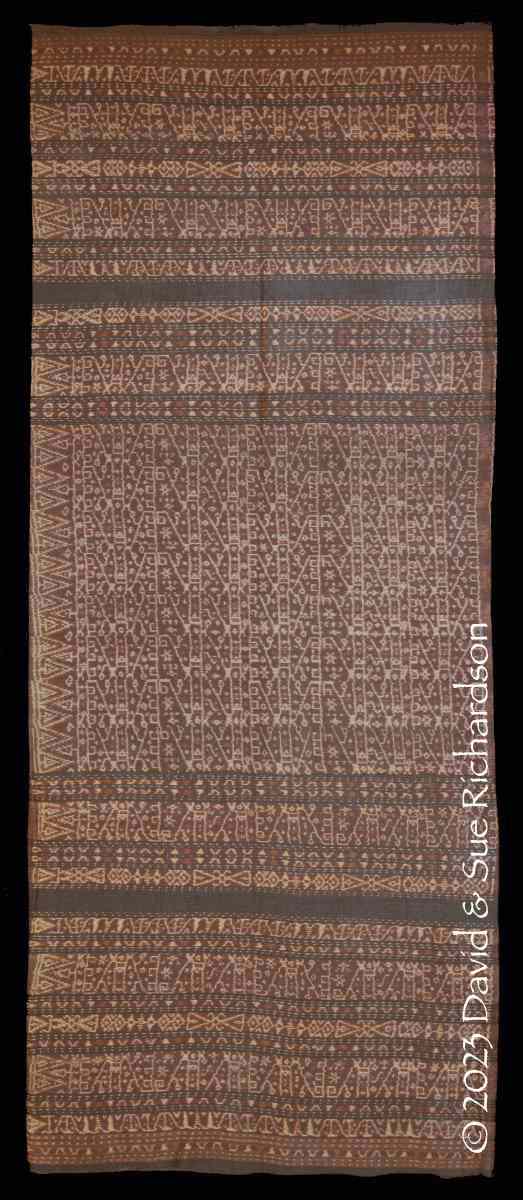

The following example was woven by the late Rufino Rambu from the aristocratic house of Sa’o Leke Bewa, who died 30 years ago. It was made in the 1960s.

A lawo barai woven by the late Rufino Rambu, Size 184cm by 70cm. Richardson Collection.

The overall pattern of the lawo has been arranged so that all of the warp ikat bands on each side are traversed by three vertical columns – the one positioned on each side of the side seam filled with a row of tumpal-like triangles, and the two others constrained by toothed tramlines filled with alternating six-armed figures and double diamonds.

Return to Top

Lawo Luka Sémba

The lawo luka sémba was inspired by the design of Nggela’s most famous cloth, the man's luka sémba or luka sindé. The pattern is clearly based on the chhabdi bhat 'flower basket' pattern found on a common type of Gujarati export patola – Alfred Bühler’s motif types 11 and 12. In Nggela the flower basket design is known as the sémba pattern. The Lio refer to Gujarati patolas as sindé.

Several Nggela weavers, such as Mama Anastasia, have emphasised to us that locally they refer to these sarongs as lawo luka not lawo luka sémba or lawo luka sindé. In nearby Wolojita they are called lawo sindé.

In the past lawo luka were mainly worn at adat rituals, but today they are worn at any formal event.

A pair of lawo luka sémba on display in Nggela

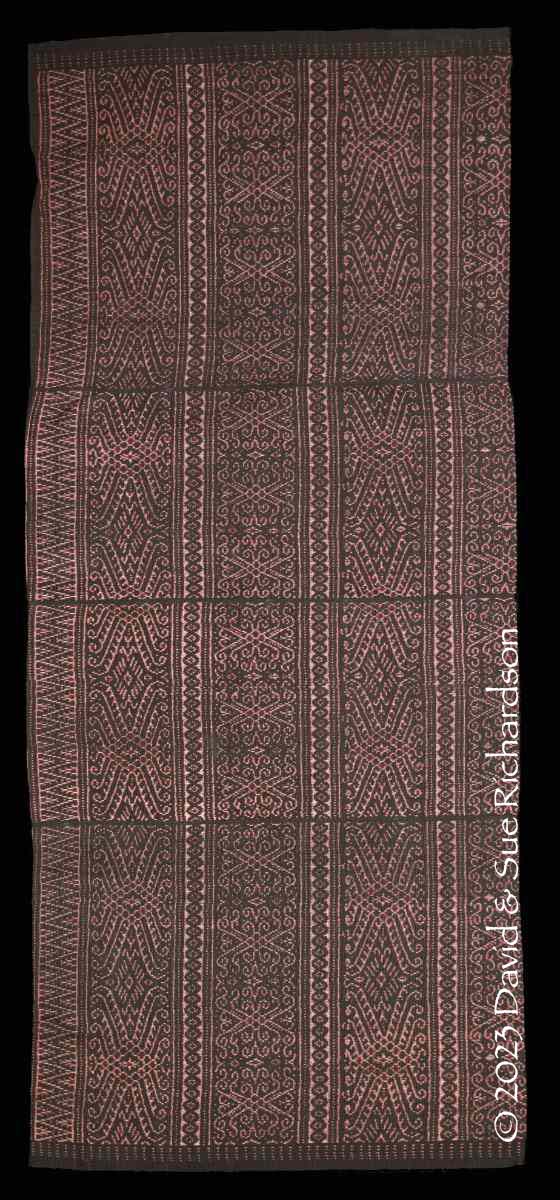

One of the finest makers of lawo luka was the master weaver Elisabeth Pango, locally known as Mama Ango, who was born in Nggela in 1947 and lives on the southeast side of the oné nua. Her father was the mosa laki of the aristocratic house Sa’o Sambajati, and her husband was a farmer. Her first example was finely woven from exquisitely ikatted commercial cotton naturally dyed with indigo and morinda. The alignment of the three panels is very precise, and the panels have been extremely neatly joined and seamed by hand. This was one of six identical sarongs completed by Mama Ango in about 1997 when she was 50-years-old. They took 10 years to make.

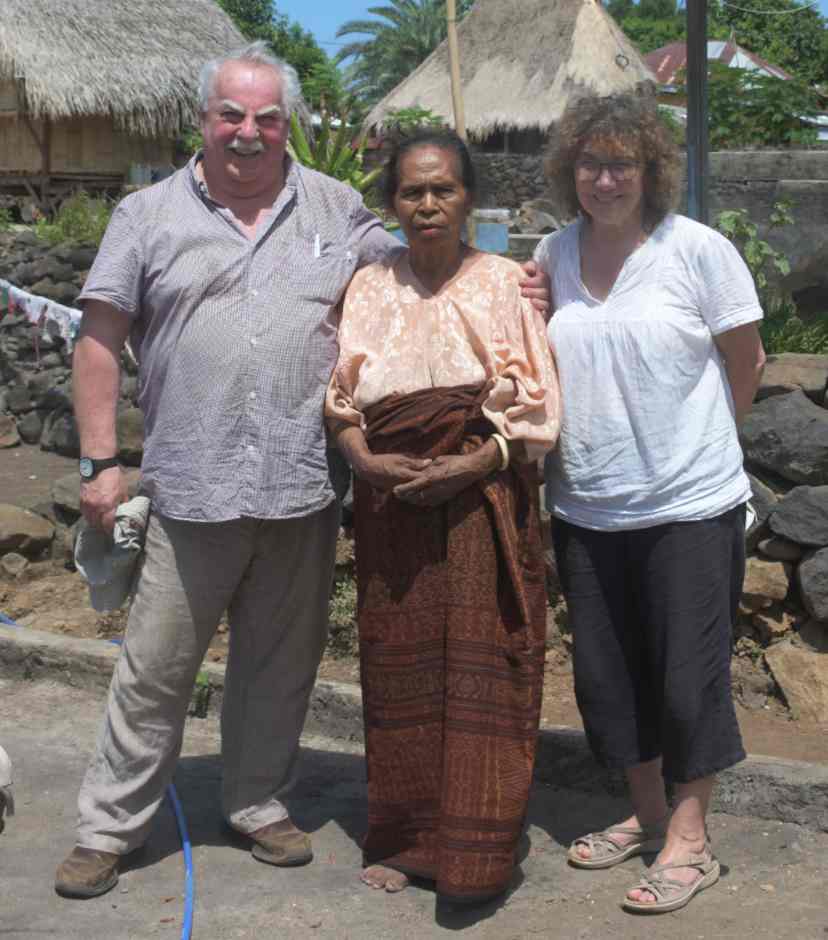

Above: A lawo luka woven by Elisabeth Pango (Mama Ango) in 1997. Size 159cm by 67cm. Richardson Collection. Below: The authors with Mama Ango, holding the last of her six lawo luka

A second example has an identical pattern but a darker tone and was finished by Mama Ango about one decade later.

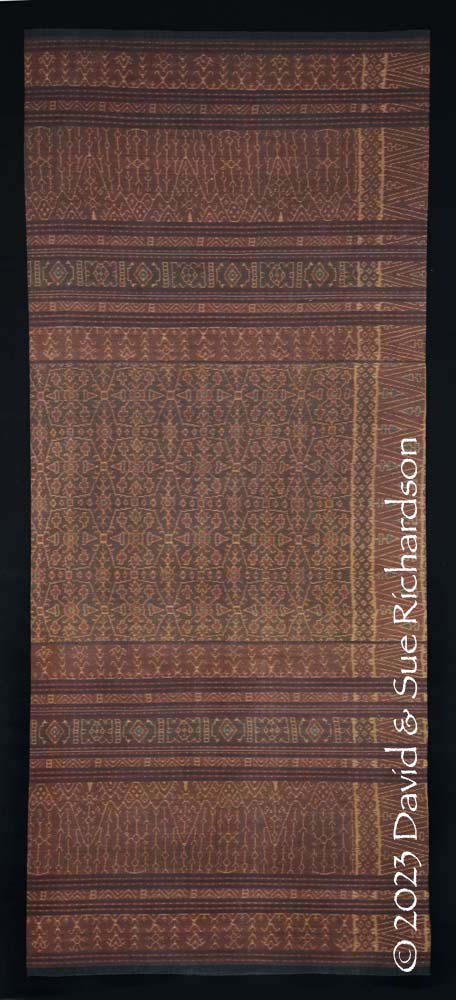

A lawo luka completed by Elisabeth Pango (Mama Ango) in 2009. Size 157cm by 68cm. Richardson Collection.

The lawo luka has a very regular design, with the centre panel completely filled with a precisely aligned lattice of mata ke’a motifs, floral eight-armed figures enclosed by an octagonal border. The end panels are decorated with a cluster of ikat bands separated by narrow warp stripes, all but one of the bands having been dyed exclusively with morinda. The exception consists of a row of diamonds enclosed by rectangles that has first been dyed with indigo and later overdyed with morinda. The widest band with parallel vertical lines and triangles is called gha'i nake, and represents the footprints of the ancestors. The centre field and the lateral ikat bands are all bounded by a longitudinal band of interlocking triangles, having the appearance of a row of terminal tumpal motifs.

The centre field, the indigo and morinda ikat band and the longitudinal band all contain small highlights of blue.

The lawo luka design was once taboo (piré) and, in the past, could only be tied by post-menopausal women. If younger women bound such designs, they could become barren or die prematurely. However, the lawo luka is not an early design and was probably developed later after the appearance of the lawo mogha.

It is obvious that the centre field pattern and possibly the longitudinal band of interlocking triangles have been directly copied from the Gujarati chhabdi bhat export patolu (Bühler’s motif types 11 and 12). Under the Dutch, patolas were given as gifts to high-status local rulers in exchange for their political and economic cooperation (de Jong 2020).

However, today’s weavers in Nggela regard the design as indigenous, created by their own ancestresses. They do not interpret the octagonal mata ke’a motif as a flower basket but as a symbol of the body of a human being, with a liver, a heart, a backbone and hips (de Jong 2016c, 108). Despite this commonly held view, Mama Ango had a different interpretation, informing de Jong that there were two meanings to the word ke’a. One was a lidded hexagonal basket used during planting and harvesting ceremonies to hold rice or other foodstuffs. The other was a coconut shell dish used during ceremonies as a food receptacle for holding meat.

The third high-quality example was produced by Mama Flor during the 1980s. The layout is identical to the lawo lukas made by Mama Ango, indicating how this pattern has become standardised.

A lawo luka woven by Mama Flor in the 1980s. Size 159cm by 66cm. Richardson Collection.

Willemijn de Jong discovered that the designs of both the important ritual luka sémba shoulder cloth and the corresponding lawo luka tube skirt had been much refined more than half a century ago by a greatly respected Nggela ikat binder called Nenek Nduru, who was particularly active between the 1940s and the 1960s (de Jong 2016a). Since that time, many weavers seem to have followed her pattern design closely. De Jong published a comment made by Mama Regina Hara:

Before Nenek Nduru tied the luka sémba, this cloth was not yet so widespread, and only selected persons were allowed to tie this cloth. Nenek Nduru made the luka sémba well-known.

Back in the 1980s, Regina Hara still owned a lawo luka made around 1955 by Nenek Nduru. In difficult times, she and her husband would light a candle and use the lawo luka as a totem, calling on the support of the ancestress (de Jong 2016c, 106).

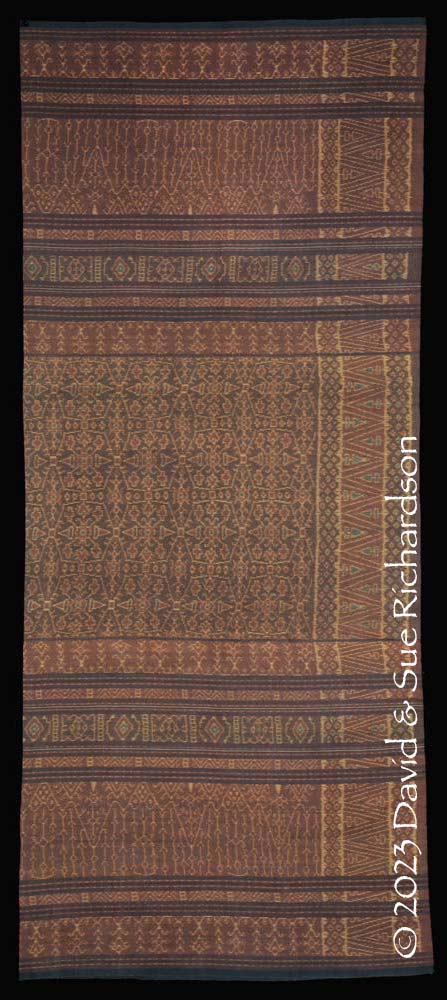

The fourth example was woven by Anastasia Tekke, who was born in Nggela in 1946. Made from commercial cotton it was naturally dyed with indigo and morinda. However in this case the indigo and the morinda were dyed more intensively, thus producing a darker tone. The alignment of the three panels is very precise.

Above: A lawo luka woven by Anastasia Tekke in 1994. Size 183cm by 71cm. Richardson Collection. Below: A lawo luka woven in Nggela, weaver unknown. Size 159cm by 79cm. Richardson Collection.

A very similar design is woven n the Mbuli Valley, where it is known as a lawo hainake rather than a lawo luka. We have also seen examples at Wolowara market and at Jopu, to the southwest of Wolowaru.

A chemically dyed lawo hainake displayed at Jopu

Return to Top

Lawo Wenda Jara

Lawo wenda jara are decorated with jara or horse motifs. They have a plain black band in the border panels indicating that the design has been borrowed from the Endenese zawo jara. Some refer to them as lawo wenda jara nggaja with a lattice of small horses and large elephants, sometimes interpreted locally as a horse with two small foals.

It is possible that the stylized stick-like nggaja elephant motif may have been inspired by the elephant motifs on certain high-status Gujarati patolas. It has alternatively been suggested that the horse motif may have been borrowed from early Dutch gold pieces, which were imported as tokens for local elites (Gittinger 1979, 49).

The example below was made in 2012 by Mama Lucia Mangelana Mana, who is a member of Kelompok Kema Sama. She was born in 1953 and belongs to Sa’o Ria. The lawo was woven from very fine commercial 2-ply nylon warps and a coarser brown cotton weft. The warps were dyed with two different synthetic dyes, one light brown and the other mid-brown. The ikat binding is incredibly accurate.

Above: The lawo wenda jara made by Mama Lucia Mangelana Mana in 2012. Size 153cm by 66cm. Richardson Collection. Below: A detail of the pattern.

Mama Lucia explained to us that the term wenda comes from the ancestors and nobody knows what it means today.

The following lawo wenda in the Fowler Museum Collection was collected in 1988 from a Lio family from Nggela who were living in Ende city. According to Roy Hamilton the pattern was derived from the Ende elephant motif style known as zawo nggaja tendo, which consists of a field of elephant, horse and diamond motifs. In Nggela the pattern has undergone minor reorganisation to create a distinctive new style. Hamilton believes that Nggela weavers do not identify the motifs in the same way as Ende weavers, no longer recognising the identity of the elephant shape. Instead, they refer to the elephant shape as jara and mystifyingly identify the diamond shape as the nggaja or elephant.

A lawo wenda. Fowler Museum, Los Angeles

According to de Jong, lawo wenda jara may have been worn by noble women belonging to the Nggondé matri-clan, whose totem was the horse. However, if any of these women married into the Sa’o Ria patrilineage, they were forbidden to wear it, possibly because they were members of the two founding patrilineages and were obliged to wear Nggela designs. Today anyone can wear this pattern.

A synthetically dyed lawo wenda jara nggaja in Nggela

The final example was woven by Mama Riri with a combination of rayon and cotton, dyed with a mixture of indigo and synthetic dyes.

A lawo wenda jara nggaja woven by Veronika Riri (Mama Riri) in 1999. De Jong Collection.

The lawo wenda jara pattern seems to be particularly popular with older women in the south Lio region.

Return to Top

Lawo Kapa Ria

Lawo kapa are decorated with a centre panel filled with a diagonal lattice of diamond-shaped motifs, enclosing a pair of mirror image figures that have the appearance of a boat (kapa) that has a single mast and possibly two triangular sails. There are two types: the lawo kapa ria with a large ship and the much rarer lawo kapa lo’o with a small ship.

Some villagers associate the motifs with the boats that brought the ancestors of the southern Lio from across the seas to Flores. Others suggest that they are based on Portuguese ships, which seems unlikely.

The lawo kapa ria

The lawo kapa appears to be a later design, probably created as a variation of the rhombic redu motif found on the lawo redu. Some villagers say that it was created by the important Nggela weaver Nenek Toja. Many examples include a pair of black pake mite bands, which generally point towards a link with Endenese designs. However, others do not.

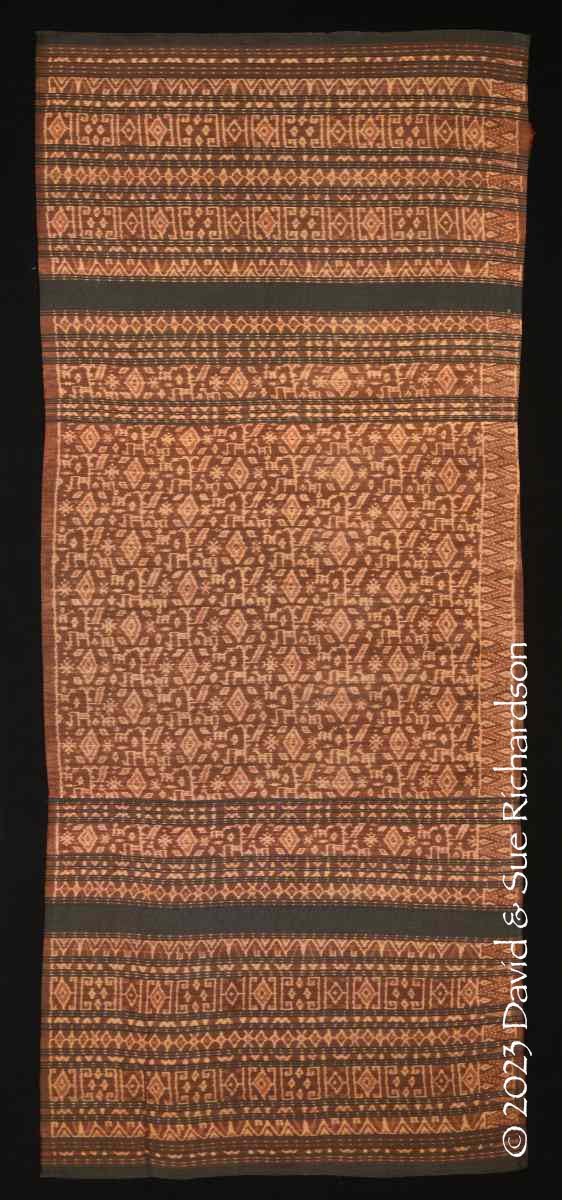

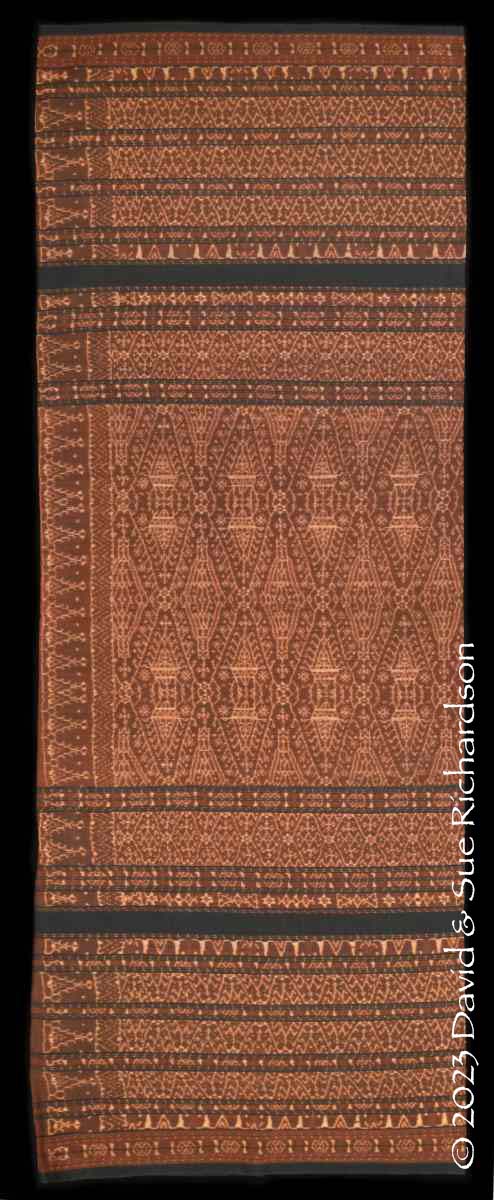

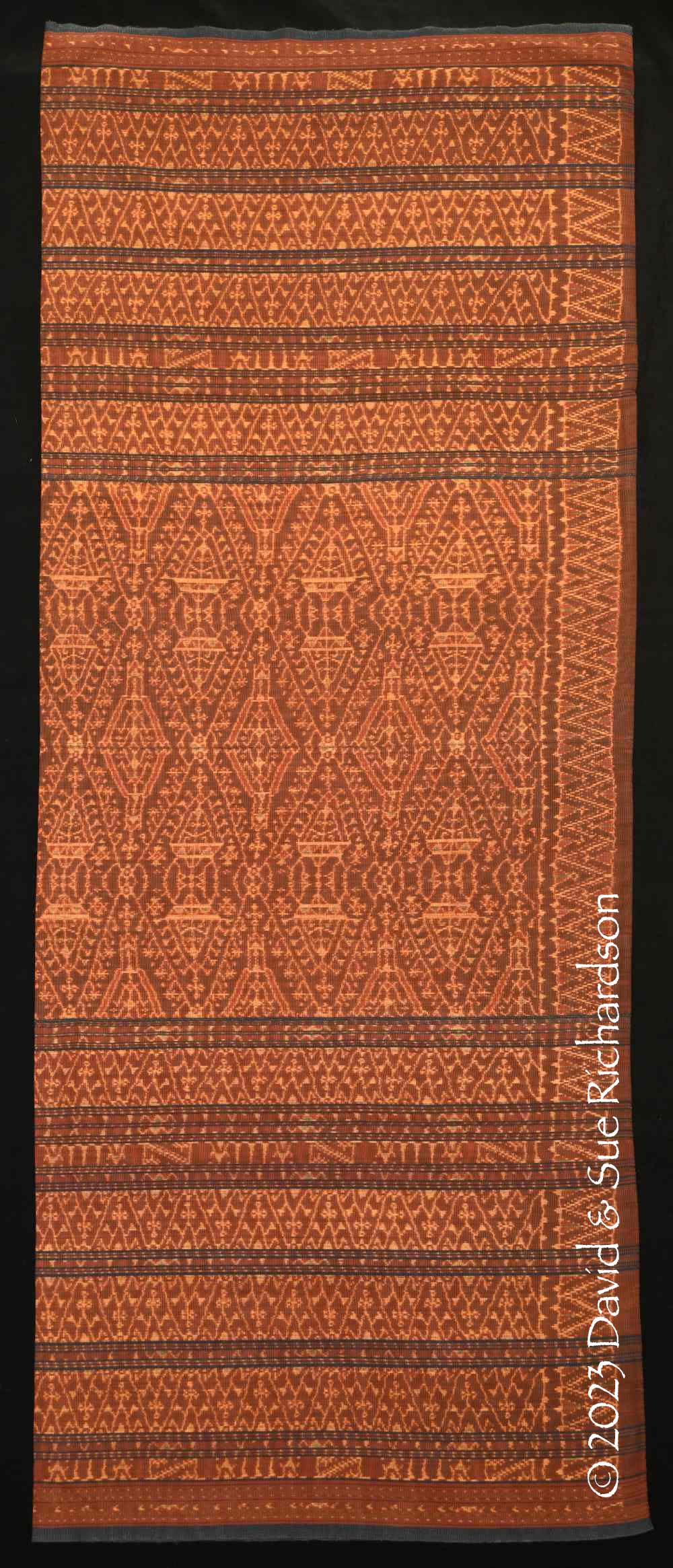

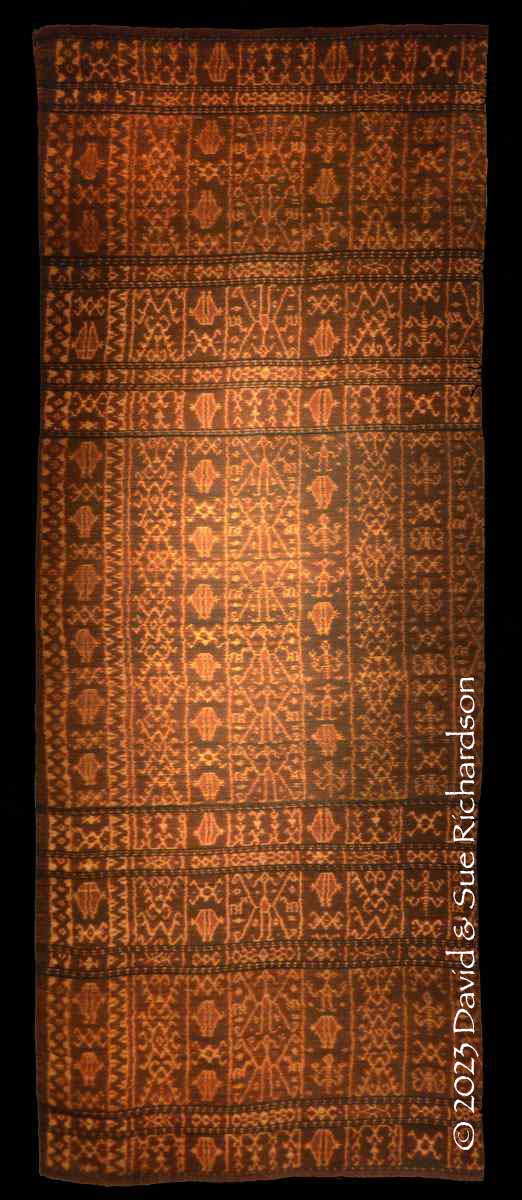

The following example was made in 1985 by Marselina Wéndé, known as Mama Seli, who was born in 1956 and belongs to Sa’o Ria. Her husband is a farmer who grows corn and vegetables and is the nephew one of the three mosa laki based in Sa’o Ria. The ikatted yarns have been dyed with morinda, whereas the black plain stripes and bands have been dyed with indigo mixed with a chemical black.

Above: The lawo kapa ria made by Mama Seli in 1985. Size 196cm by 73cm. Richardson Collection. Below: The kapa ria motif

A similar lawo kapa ria was made in Nggela one year later in 1986 by Mama Fabiola Keto, also from Sa’o Ria. She died 23 years ago aged 73. It was acquired from her daughter. It was woven from commercial two-ply rayon that had been synthetically dyed.

A lawo kapa ria woven by Mama Fabiola Keto in 1986. Size 156cm by 68cm.

Richardson Collection.

Another example was made by Mama Si’o, who died a long time ago. It was acquired from her granddaughter who thought it was about 50 to 60 years old. Made from commercial two-ply cotton with hand-spun stripes, it was dyed with indigo and morinda. The skirt contains many small indigo details, such as the small triangles in the hulls of the kapa boats.

A lawo kapa ria woven by Mama Si’o. Size 183cm by 68cm. Richardson Collection.

The next example was woven in 2006 by Anastasia Bhoa (Mama Anas) using a mixture of rayon and cotton yarns. The bound yarns were initially dyed with indigo, and subsequently dyed with a synthetic dye. De Jong found that this was a common technique used in Nggela between 1975 and 2010.

A short lawo kapa ria woven by Anastasia Bhoa (Mama Anas) in 2006. De Jong Collection.

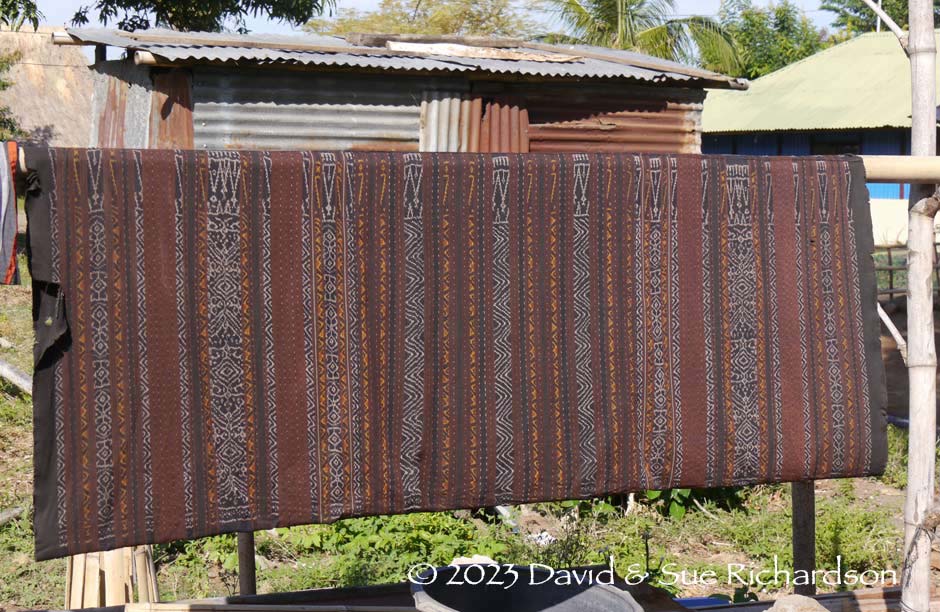

A lawo kapa ria drying in Nggela

The final example of a lawo kapa ria has narrow black pake mite bands.

A lawo kapa ria. Private Collection

Lawo Kéli Mara Té’a

The lawo kéli mara té'a has a central field composed of pairs of kéli mara motifs, one inverted above the other in the form of a diamond. The motifs look very similar to the kapa ria motifs, shown above. Té’a means elder, mature or ripe.

The lawo kéli mara té'a. Private Collection

There is a little confusion about the origin of the kéli mara pattern, which supposedly represents Kéli Mara, a mountain located to the northwest of Ende city. Willemijn de Jong initially reported that it was created in the post-independence 1960s by an elite Nggela woman who had lived for some time in Ende town (1994, 224). More recently she wrote that the lawo kéli mara was created in the 1950s (de Jong 2020). Meanwhile her colleague Wyss-Giacosa from the Department of Ethnology at the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zurich has claimed that the genealogy of the lawo kéli mara can be traced back to the 1950s and is connected to the important weaver Nenek Toja (Wyss-Giacosa 2016).

However, our informant Margarita Gera (Mama Rita) claims that her grandmother made a lawo kéli mara when she was a young woman. Her grandmother must have been born during the period 1895 to 1900 since she died in 1965 at the age of 65 to 70. If correct this would suggest that the motif must be at least 80 years old, dating from before the Second World War.

A lawo kéli mara té'a in the collection of the Museum for Textiles, Toronto

Lawo Nggamba

The lawo nggamba is a new design created by master binder and weaver Elisabeth Pango, affectionally known as Mama Ango. The central panel is decorated with a lattice of interlocking hexagons, each cell containing the nggamba or spider motif – a diamond shape sprouting eight or more legs.

A lawo nggamba woven by Elisabeth Pango, known as Mama Ango, aged 70.

Mama Ango’s father was a leader (mosa laki) of the aristocratic house Sa’o Sambajati, located in the southern zone of Nggela called Bhisu Mbiri. She learnt to weave after finishing primary school, never going on to attend secondary school.

Return to Top

Lawo with Vertical Bands

Lawo with vertical bands of motifs on a red-brown ground are almost as highly valued as those with a centre panel. However they appear to have been a recent development. According to Willemijn de Jong, the lawo pundi was the first type of vertically patterned sarong, and was probably only created in the 1960s (de Jong 2020a, 27). One wonders whether its design may have been inspired by some of the vertically structured zawo produced by the Endenese.

Sarongs with different vertical patterns have become fashionable among younger women over recent decades (de Jong 2020, 28).

Lawo Pundi

The lawo pundi is one of the two most important sarongs in the vertical sections category. It has a layout of vertical ikat sections containing a variety of motifs, one of which is normally the rhombic-shaped pundi motif. The vertical sections are not continuous, but are segmented by lateral warp stripes and sometimes lateral ikat bands. Morinda-dyed examples are sometimes called lawo pundi kembo.

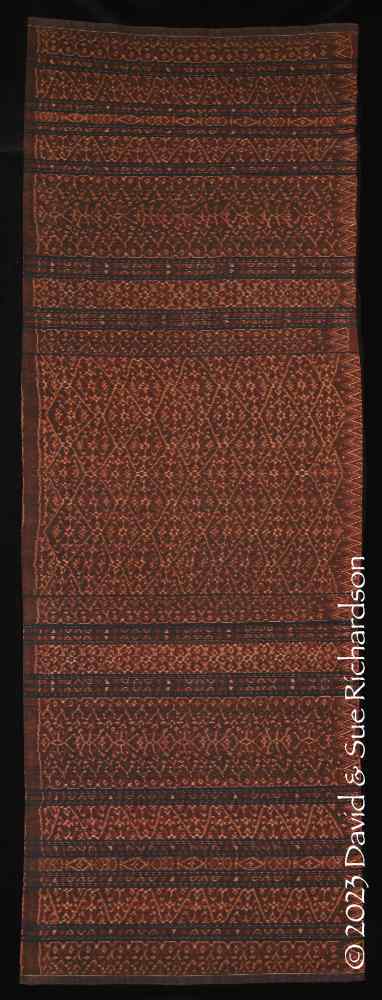

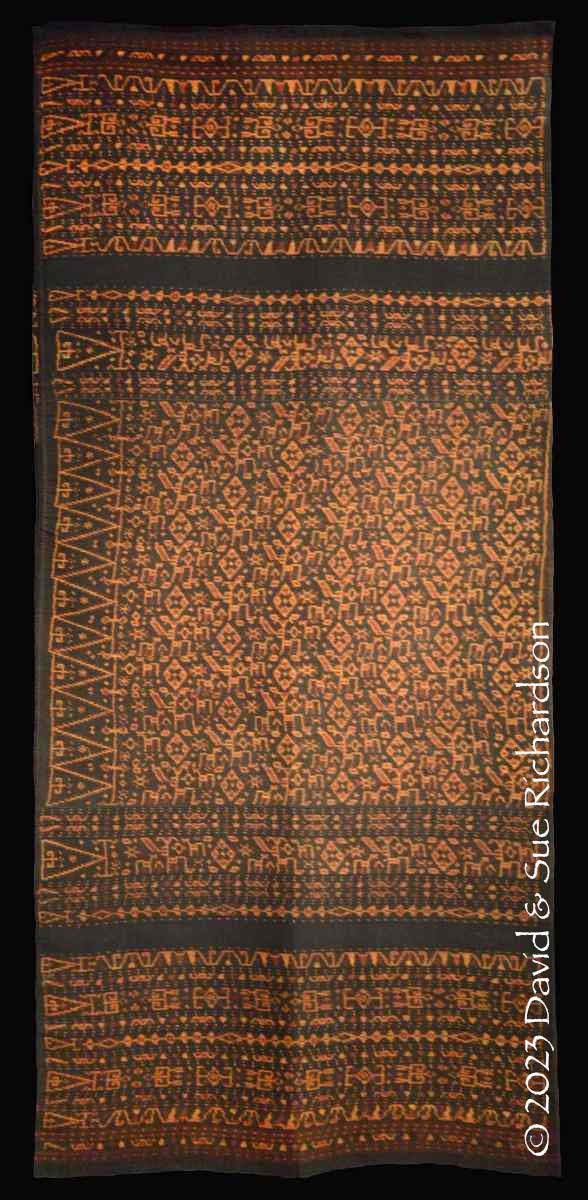

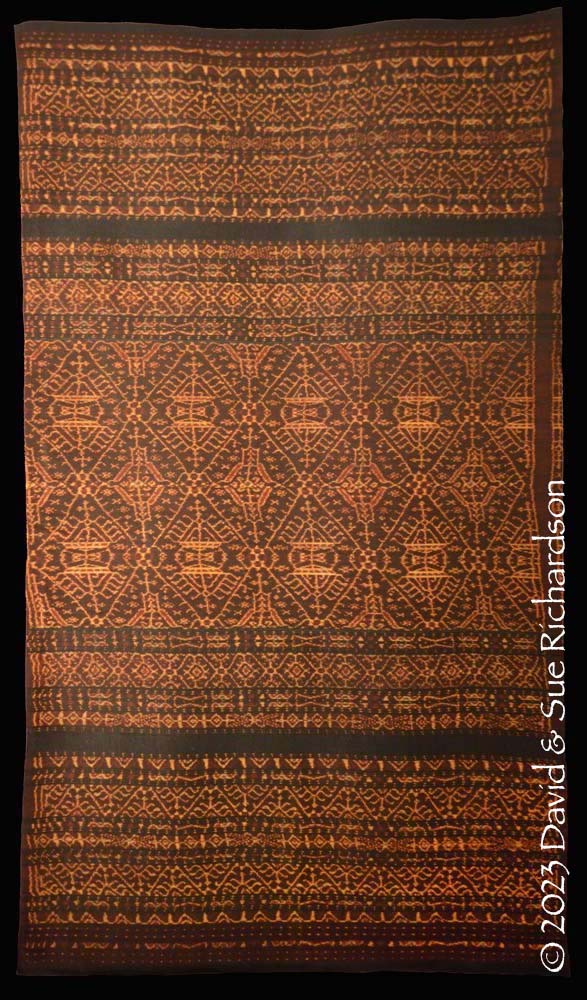

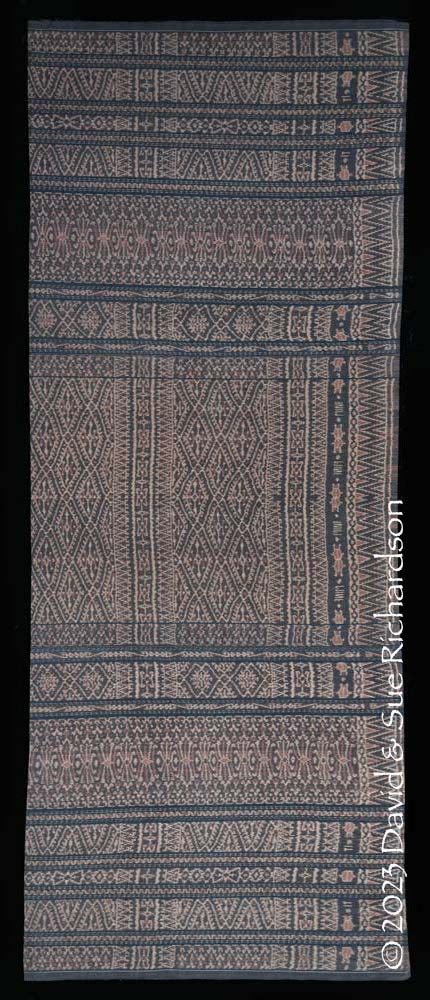

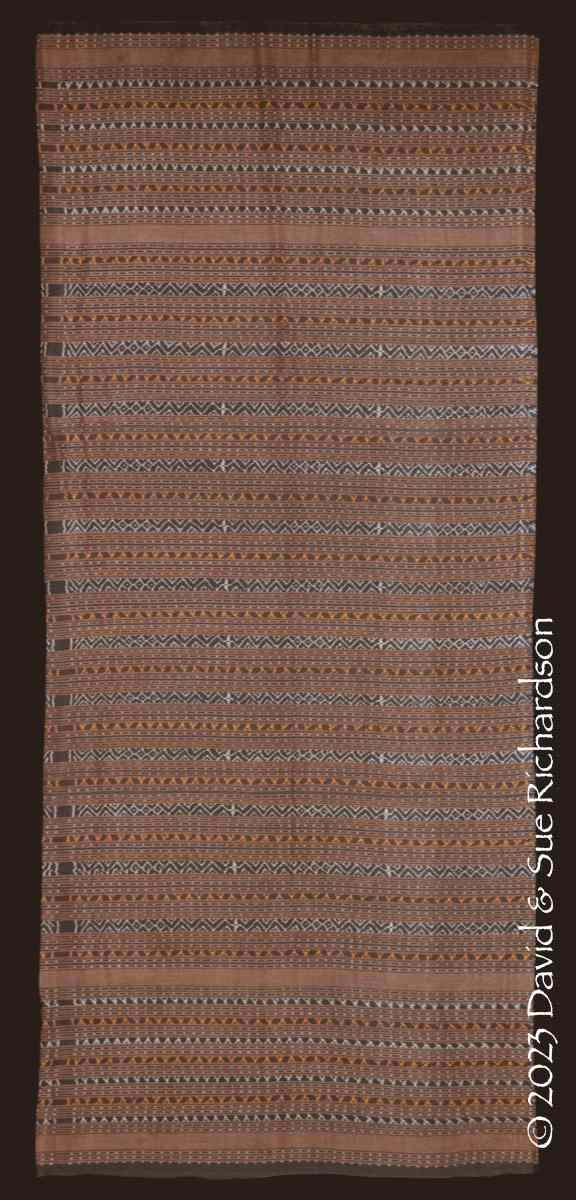

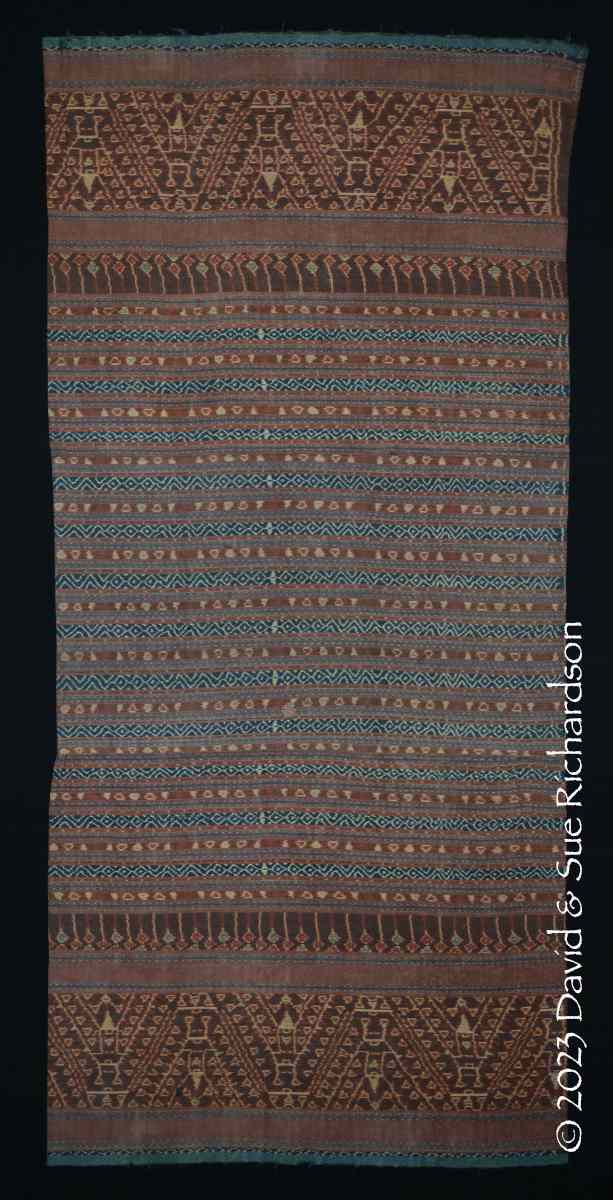

The following lawo pundi was woven in the 1950s by the late Mama Lena Rupa, who belonged to Sa’o Leke Bewa, located in the southern zone of the oné nua. She stopped weaving in her later years and died in 1975. Her lawo pundi was woven from commercial cotton that had been naturally dyed with indigo and morinda. Most of the indigo has been overdyed, apart from small parts of the design, which remain as blue highlights. The outer selvedges of the outer panels have been woven with a narrow band of complementary warp.

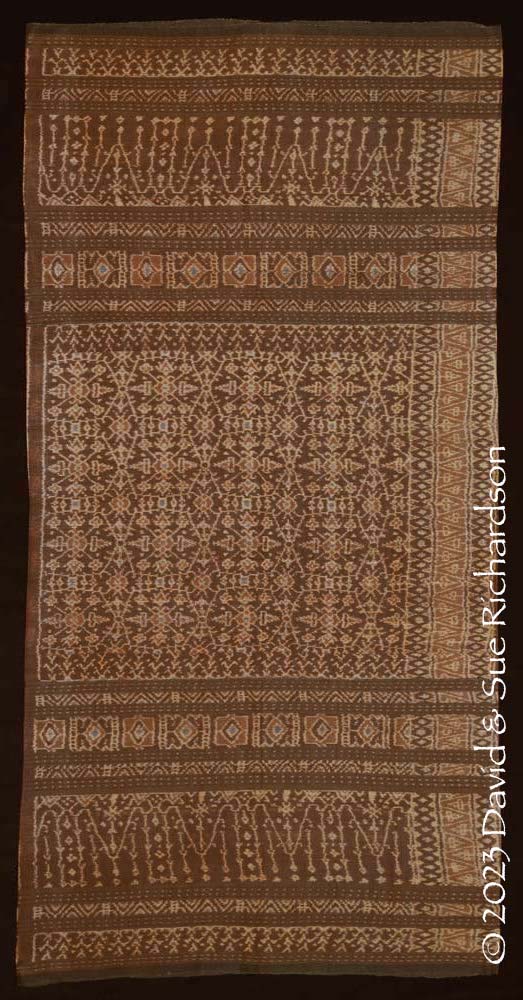

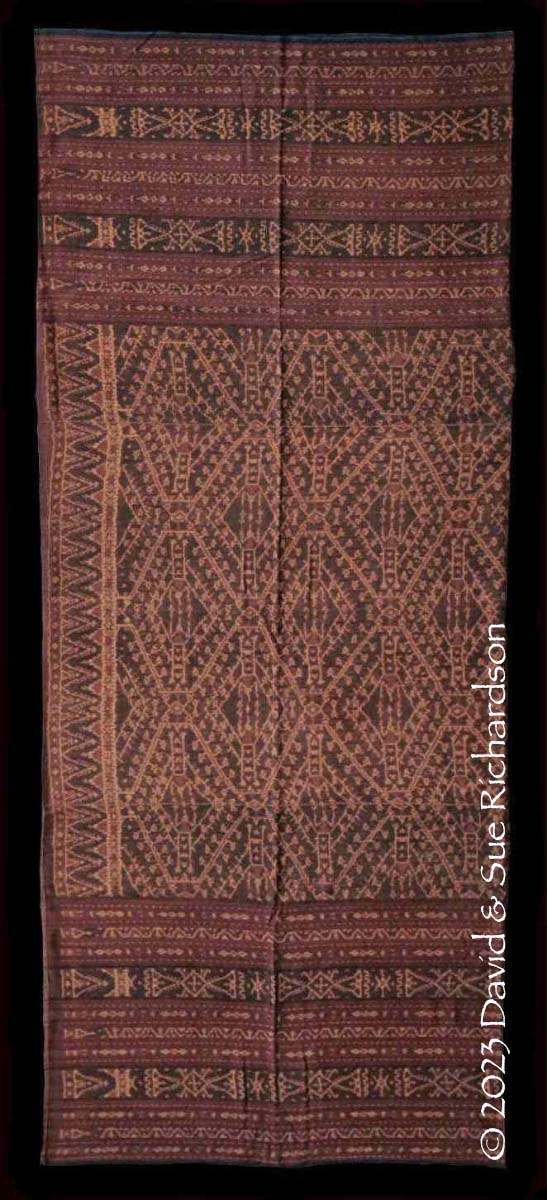

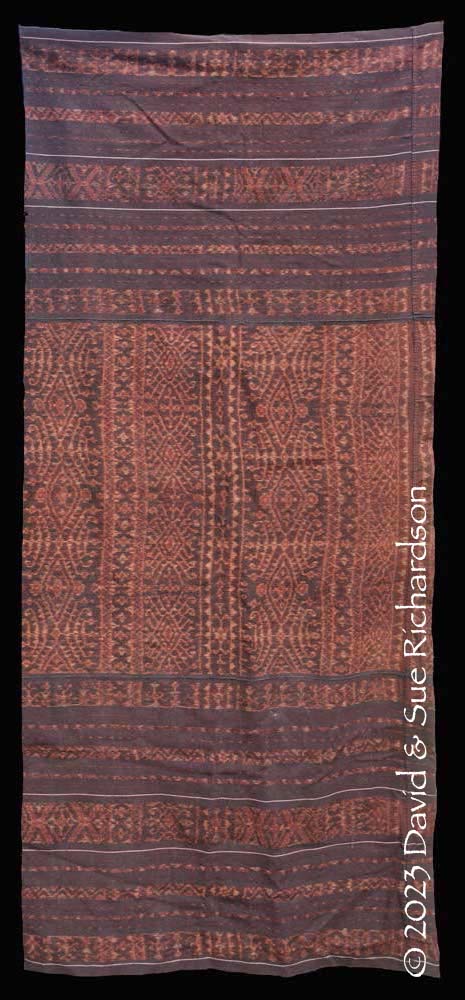

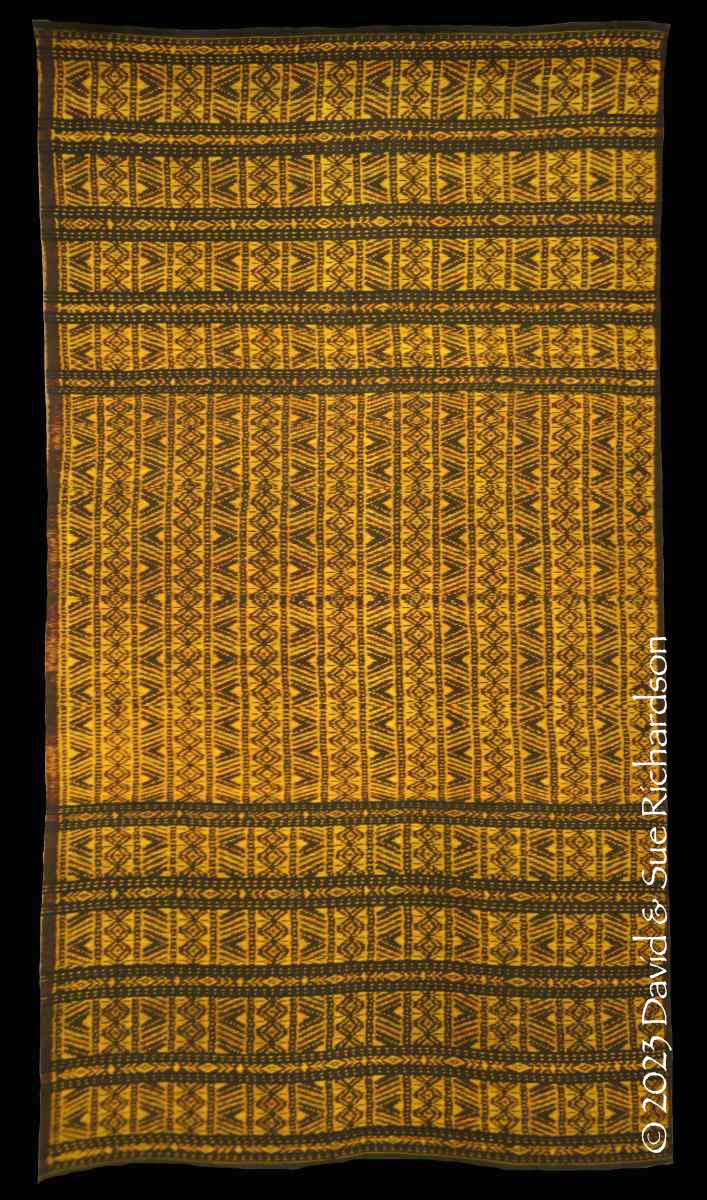

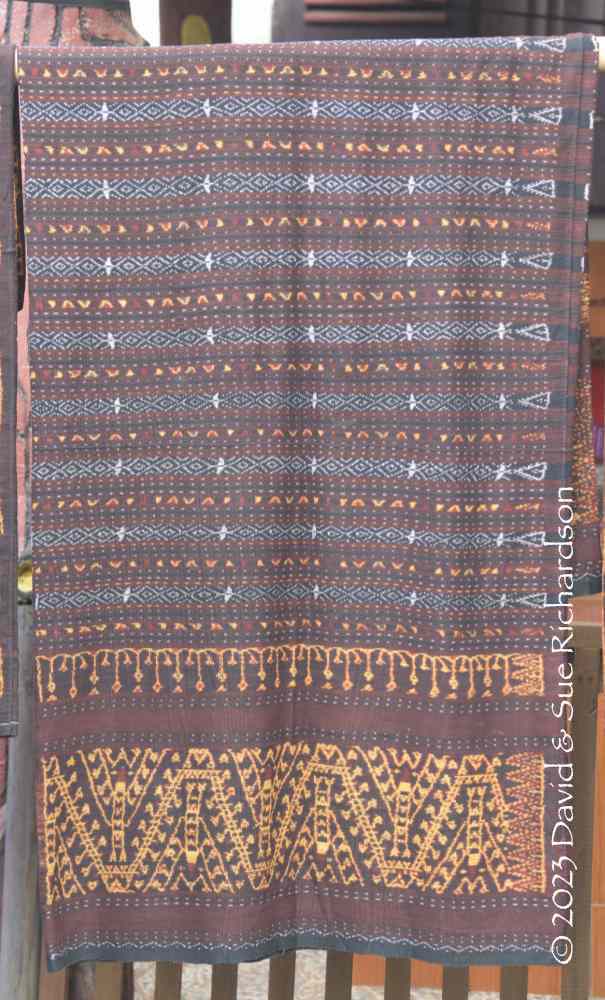

A lawo pundi woven by Lena Rupa in the 1950s. Size 170cm by 66cm.

Richardson Collection.

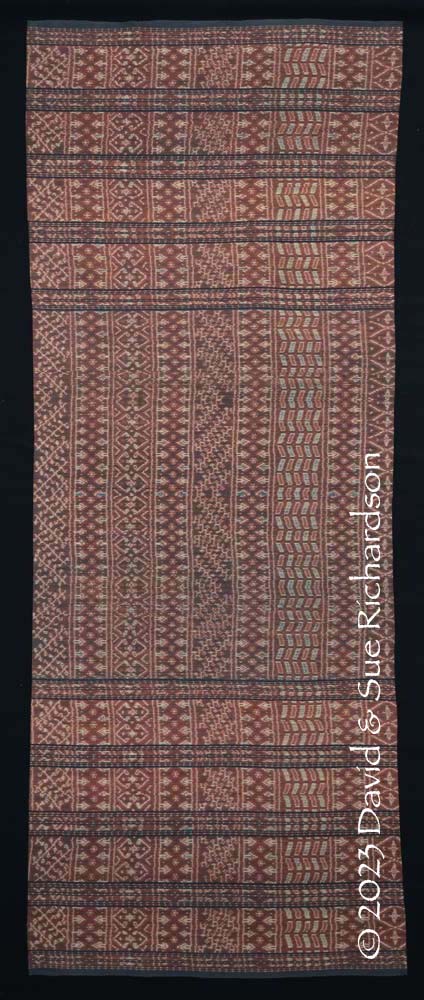

The second exceptionally high quality lawo pundi kebo was woven from commercial cotton that had been naturally dyed with indigo followed by morinda, leaving many light blue highlights. The alignment of the ikat pattern in the three panels is very precise and they have been joined together and seamed by hand in an extremely fine manner.

A lawo pundi kembo woven by the late Mama Nae, the mother of 70-year-old Gertrudus Nae, in approximately 1980. Size 172cm by 69cm. Richardson Collection.

The origin of the pundi design is uncertain, but de Jong suggests that it was created in the post-independence period, allegedly inspired by a shoulder cloth from the coastal Lio village Wolotopo, just east of Ende city. She estimated that it was probably created in the 1960s, although given the provenance of the first example shown, it may have been somewhat earlier. We were told by one informant that the pundi motif was supposedly based on a Chinese coin.

The lawo pundi became highly fashionable for several decades and is now a classic sarong worn by all generations. It was probably responsible for inspiring the creation of several later designs of vertical section sarongs.

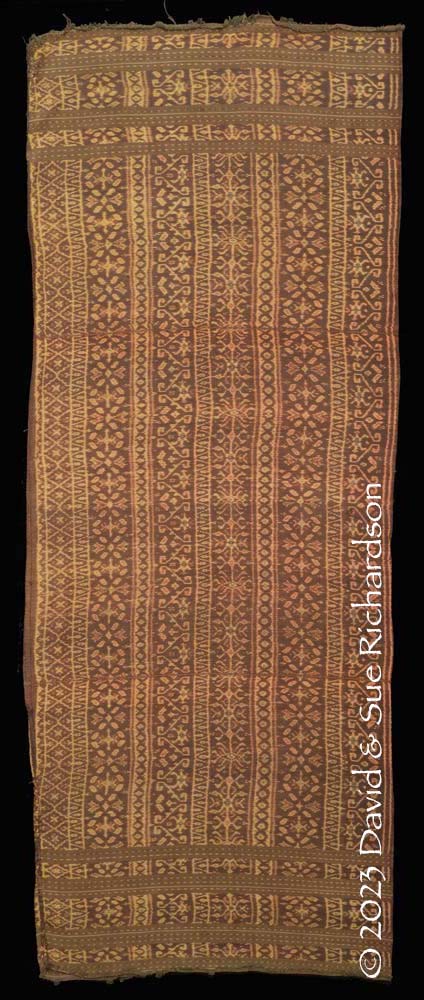

A very old lawo pundi acquired in Nggela, weaver unknown. Size 168cm by 68cm.

Richardson Collection.

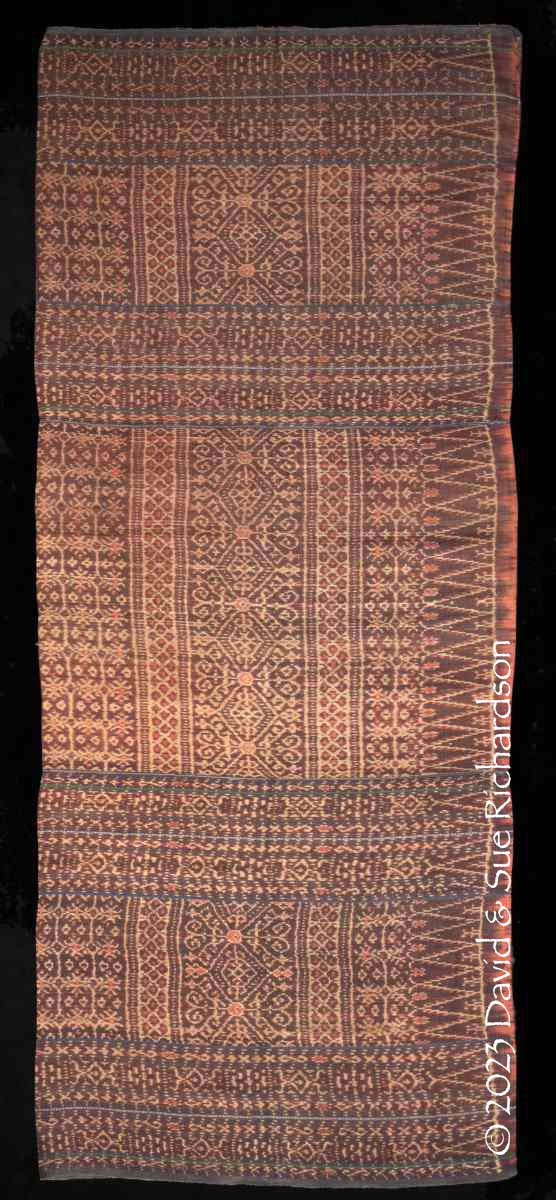

A lawo pundi collected in 1994. No provenance. Size 145cm by 60cm.

Richardson Collection.

Lawo pundi were worn by the wives of the mosa laki and other village elders, as well as by the daughters of the mosa laki for performing the muré dance. We were also told that the lawo pundi was once only worn by virgins. Today the lawo pundi can be worn for formal events such as a wedding or a graduation ceremony.

The following example decorated with the pundi motif was woven by Petronela Ji’e (Mama Pape) from commercial cotton naturally dyed with indigo and morinda.

A lawo pundi kembo woven by Petronela Ji’e (Mama Pape) in 2007. De Jong Collection.

A lawo pundi kembo belonging to a family in Nggela

Lawo pundi are also made by weavers in the Mbuli Valley, but sometimes have different designs.

A lawo pundi with the pundi motif displayed in Jopu

In Wolowaru and other villages in Mbuli they produce the lawo pundi kubi, with the kubi octopus motif. The following synthetically-dyed lawo kubi was made by Mama Tena in kampong Wato Rajo located on the west side of the Mbuli River, 3km south of Wolowaru.

The modern lawo kubi woven by Mama Tena in Wato Rajo. Size 168cm by 72cm.

Richardson Collection

Lawo Lere Manusia

The rare lawo lere manusia is a modern variation of the lawo pundi with sixteen narrow vertical bands decorated with a wide range of motifs, including anthropomorphic figures – hence the nomenclature manusia, meaning human beings. Other motifs include lizards, butterflies, horses and earrings.

The design was created by Sisilia Supi who participated in the Proyek Lawo Kembo (Morinda Sarong Project), launched by Willemijn de Jong in 1993 to encourage local weavers to continue using natural indigo and morinda (kembo). Because binding such a complex design is so labour intensive, lawo lere manusia are seldom manufactured.

The naturally dyed lawo lere manusia made by Sisilia Supi during the period 1997-2002

De Jong Collection.

Lawo Jara Èlo

The lawo jara élo is yet another variation of the lawo pundi, with its vertical columns decorated with stylised horse motifs. It is one of the two most important sarongs with vertical sections that is claimed to have been developed by the noble weavers of Sa’o Ria.

In the past only post-menopausal women were allowed to bind this highly prestigious pattern.

Lawo Kapa Lo’o

Lawo kapa lo'o are supposedly decorated with two ship motifs although they actually appear like variations of the rhombic redu motif (lo'o means small). De Jong says they are no longer produced.

Lawo Mata Bege Lere

The diamond-shaped bege motif was created in Nggela in 2014 by the family of Maria Ferdinanda Bela (Mama Din). It has light blue highlights.

A lawo mata bege lere woven by Maria Ferdinanda Bela in 2014

The vertical columns have different widths, creating an asymmetric design. It is somewhat similar to the Endenese lawo zombo so (zombo = border, so = divided).

Lawo Rangka

The lawo rangka, also known as a lawo kanga au, is a modern design popular with the younger women in Nggela. It is decorated with alternating vertical columns decorated with eight-hooked diamonds and diamonds enclosing a cross, the latter like a simplified form of the mata ke’a motif found in the lawo luka.

Lawo Lima Desa

The lawo lima desa is decorated with vertical columns containing anthropomorphic figures and gold earrings. It is said to be a borrowed design.

Lawo Lombo Lere

The lawo lombo lere is a new pattern that was recently created by the talented Petronela Ji'e (Mama Pape). It is composed of a large number (around thirty) of narrow vertical bands, each decorated with simple geometric figures, making it a labour-intensive pattern to bind.

The example below was made using yellow synthetic rayon yarn and a synthetic black dye:

A lawo lombo lere woven by Petronela Ji’e in 2012 to 2013. De Jong Collection.

A lawo lombo lere woven by a weaver from Kelompok Kema Sama

Return to Top

Lawo with Horizontal Bands

Lawo with horizontal bands have a lower status than those with centre fields or with vertical bands. They are decorated with alternating narrow bands of simple ikat and plain warp stripes.

Such lawo are probably some of the oldest surviving patterns. Nggela weavers disparagingly call them lawo lélu, meaning ‘thread sarongs’.

They are classical wear for elderly women. Until recently, they could not be given to kin related by marriage at life-cycle rituals. They are not acceptable for bridewealth marriage exchange.

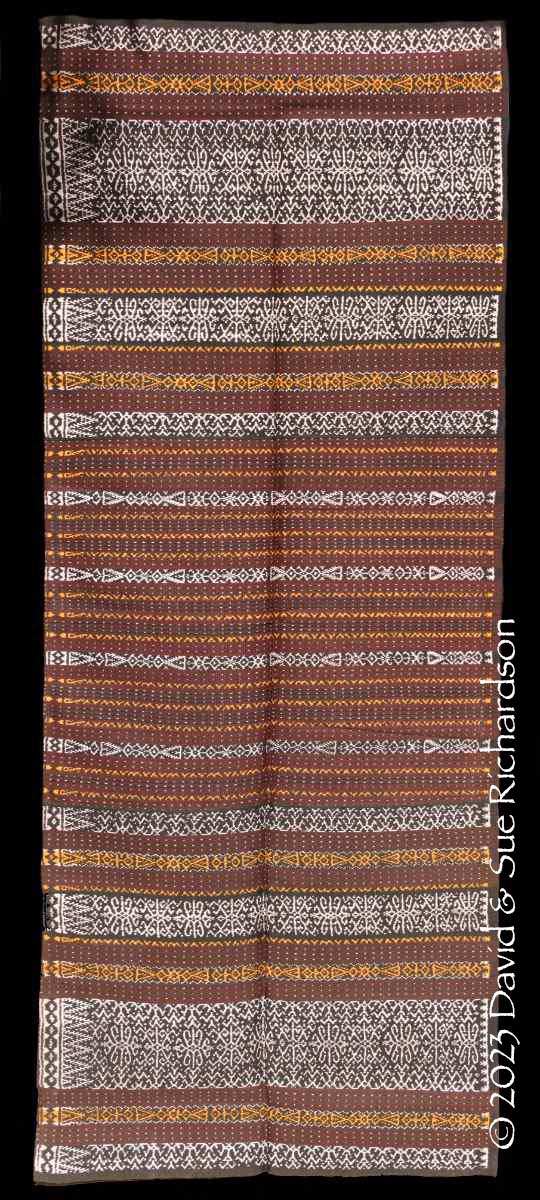

Lawo Népa Nua

The lawo népa nua, alternatively called lawo népa mité, is one of the most important banded sarongs. The lawo népa is the snake sarong, a népa being a snake and a nua being a village or traditional domain. Note that the name népa nua is pronounced ‘nipa nua’. They are decorated with narrow bands of ikat, some wider than others, the narrower bands decorated with chevron-like motifs, the wider bands with diamond-shaped motifs. Geometric motifs on népa sarongs are considered snake-like.

Mythology related to snakes can be found in many parts of eastern Indonesia. The Lio perceive snakes as metamorphosed ancestors with magical powers that can bring fortune or misfortune (de Jong 1996, 220). Snake mythology on Flores was investigated in depth during the 1960s by the Catholic SVD priest and ethnographer Piet Petu (Sareng Orinbau 1967). In his opinion, the origin of ikat weaving was closely linked to the cult of the snake, with the snake inspiring some of the first ikat patterns. Consequently, the very first ikats produced with snake-like motifs – like the lawo népa nua – were high-status sarongs providing amuletic protection to their owners.

Interestingly the Lio also often define spaces – such as villages – using the anatomy of a snake, with a head (ulu), tail (eko) and navel (pusu or pusé) (Yamaguchi 1989, 480). Piet Petu argued that the indigenous name of Flores was Nipa Nua, Snake Island. He also found that many places and villages on Flores incorporate the words for snake and dragon in their names.

Willemijn de Jong found that local adat experts, such as Mama Anas, suggest that lawo népa nua may have been the first type of Nggela ikat sarong. Unlike today, in the past they were highly valued adat sarongs. Furthermore the pattern of the népa nua seems to have been originally taboo, its binding and use being restricted to noblewomen. Over time it eventually became accessible to all women.

The lawo népa nua is differentiated into two types:

- lawo népa mité with a white and indigo or black main ikat band and

- lawo népa té’a with a yellow and indigo or black main ikat band.

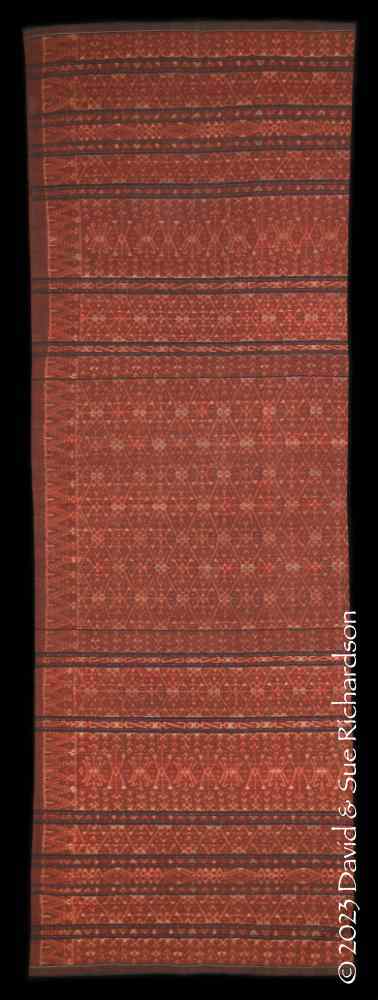

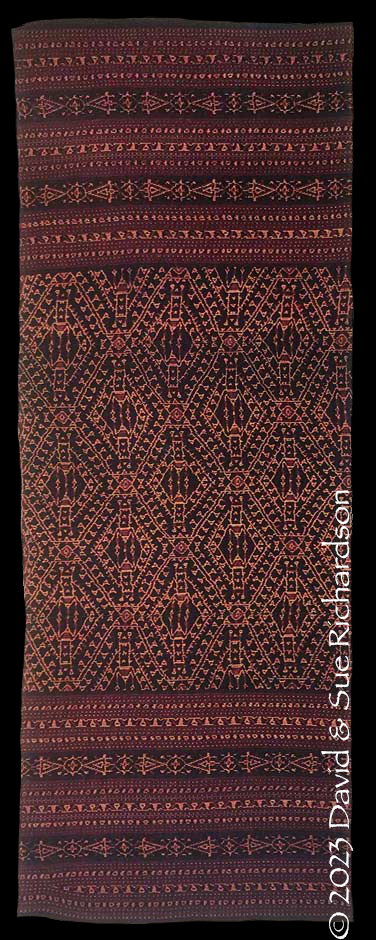

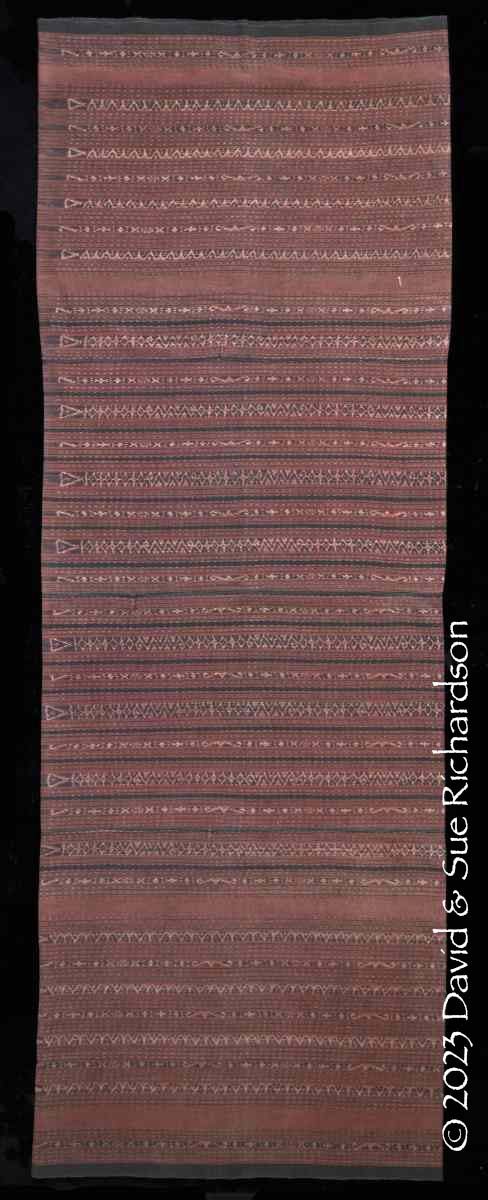

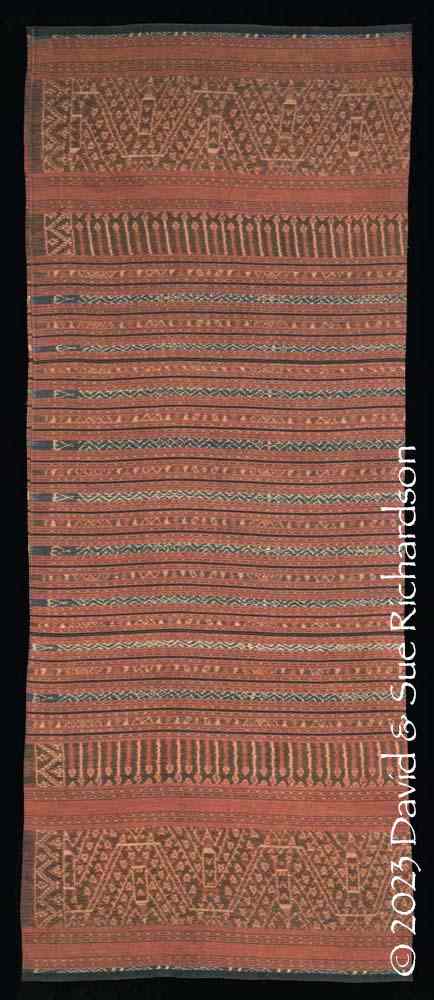

The following lawo népa nua mité was made in 2008 by Maria Delarosa Wea, known as Mama Dorti, who belongs to the aristocratic house of Sa’o Sambajati. She described it as a lawo népa Nggela.

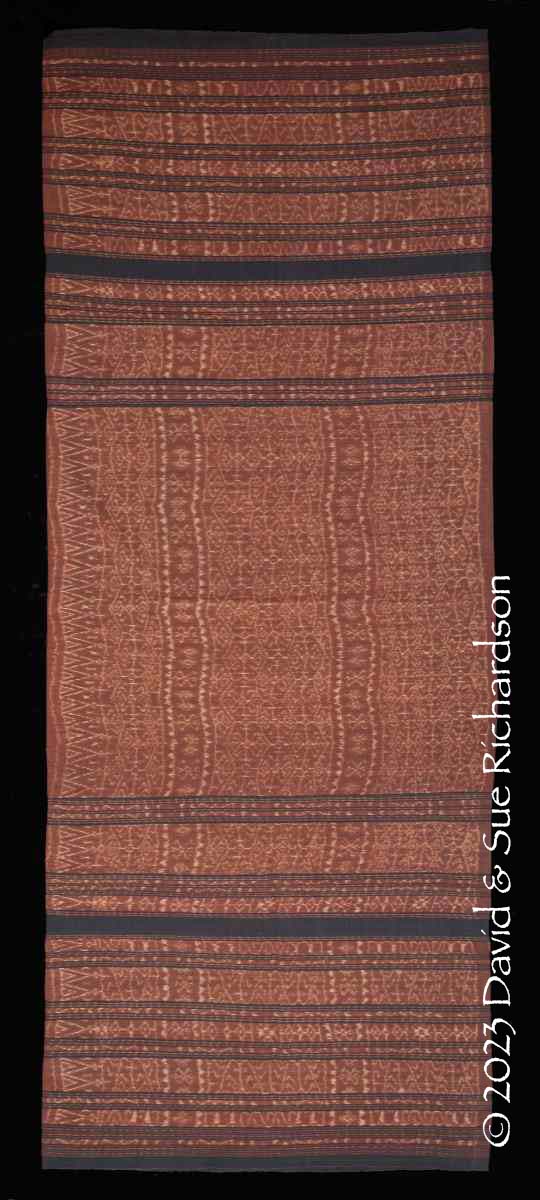

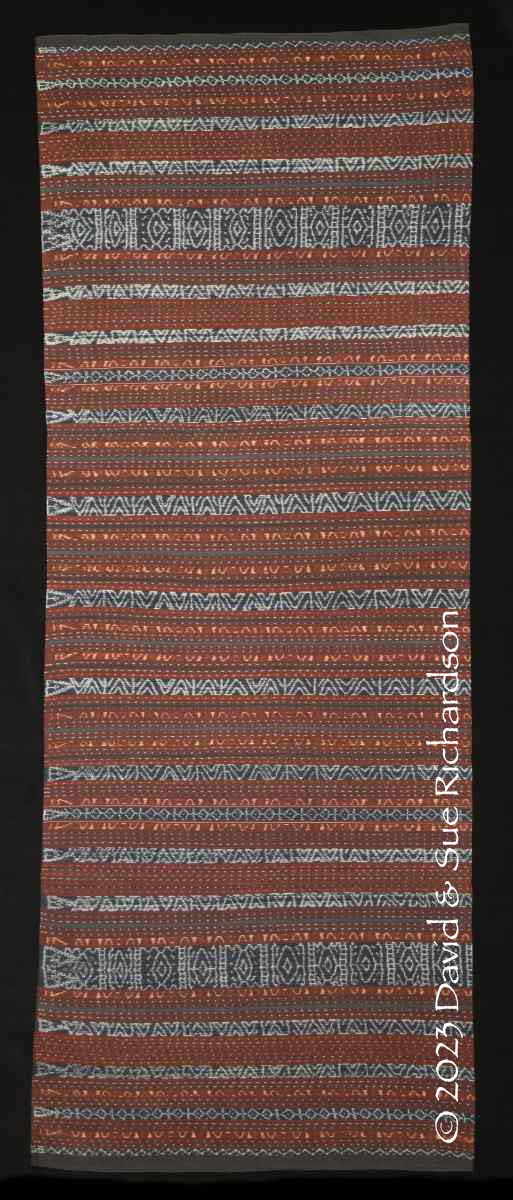

A lawo népa nua mité made in 2008 by Maria Delarosa Wea. Size 182cm by 69cm.

Richardson Collection

The second lawo népa nua mité was made by Mama Maria Ita in about 2002, when she was aged 55. It was woven from naturally dyed commercial cotton.

A lawo népa nua mité made in 2002 by Maria Ita. Size 178cm by 70cm.

Richardson Collection

A chemically dyed lawo népa nua hanging out to dry in Nggela

Lawo népa mité are also a specialty of the people of the Mbuli Valley (Sareng Orinbau 1992, 59). The following illustration shows a woman weaving a chemically dyed lawo nepa te’a in kampong Aemboi. Nepa is the pattern in the middle and te’a means yellow. She explained that this was a special sarong for unmarried women.

A woman weaving the end panels of a lawo nepa te’a in kampong Aemboi

Lawo Mogha Mité

The lawo mogha mité is an everyday sarong decorated with narrow black and white ikat bands, some wider than others. The narrower bands are ikatted with a meander, while the second widest band contains a row of diamonds, a pattern called mata bili that can only be bound by post-menopausal women. The motif supposedly symbolises the female vulva and hence fertility.

One of the panels from a Nggela lawo mogha mité

The design was probably developed by noblewomen at a later stage, after the lawo redu and lawo népa nua had lost their exclusivity and had become more widely available. Today it is no longer a prestigious design.

Very similar lawo mogha mité are woven at Jopu, Wolojita and in the Mbuli Valley.

Above: a synthetically dyed lawo mogha drying in Wato Rajo in the Mbuli Valley

Below: Mama Tena wearing a similar lawo mogha in Wato Rajo

A woman wearing a chemically-dyed lawo mogha mité at Wolojita

There is also a close variant of the lawo mogha mité with the band of mata bili motifs substituted by a band repeating the central row of motifs found in the widest terminal ikat band.

A variant of the lawo mogha made in Wato Rajo in the Mbuli Valley

Lawo Gami Teresa

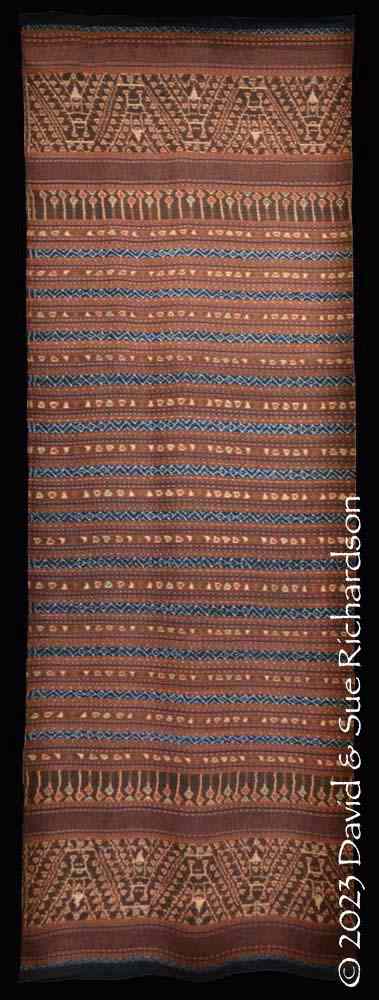

The everyday lawo gami terasa (lawo gami tere esa) is often the first design that a girl in Nggela learns to make. According to Maria Letisia Bo’a, all the women in Nggela know how to make a lawo gami terasa, even if they are unable to make the more difficult sarongs. It is somewhat similar to the lawo népa nua. The nomenclature gami tere esa derives from the fact that the simple ikat bands were composed of nine bundles of yarns known as gami, the Lio word for nine being tere esa.

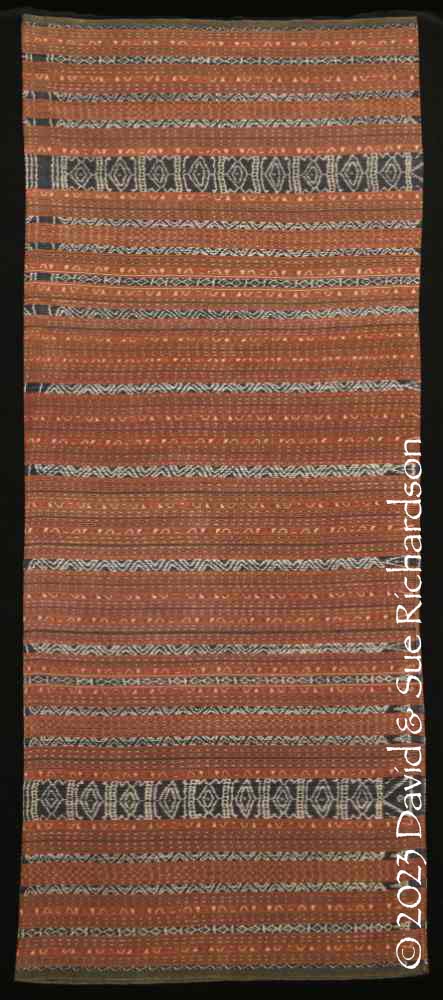

The following lawo gami teresa was woven by Maria Elmu Kulata Kawa from Sa’o Ria and acquired from her sister, Gertrudis Ero Nae. It was dyed with indigo, morinda and a chemical black. Some of the indigo shows as small highlights.

A lawo gami teresa woven by Maria Elmu Kulata Kawa from Sa’o Ria. Size 170cm by 66cm.

Richardson Collection

There is also a long version of the lawo gami teresa. The second example from neighbouring Jopu was woven using synthetic rayon and chemical dyes:

A synthetically dyed lawo gami teresa woven in Jopu in about 2000. Size 178cm by 77cm.

Richardson Collection

The third example was naturally dyed and woven in an unknown village somewhere within Kecamatan Wolojita:

A long lawo gami teresa woven in Kecamatan Wolojita. Size 190cm by 67cm.

Richardson Collection.

Unlike some of the other Nggela sarongs, the lawo gami teresa is made in a variety of different forms, some with additional bands of ikat:

A lawo gami teresa displayed in Nggela

The final example is a simple but rare two-panel lawo gami teresa woven from naturally dyed commercial cotton:

A rare two-panel lawo gami teresa photographed in Nggela in 2019

Lawo Mangga Lo’o

The lawo mangga lo’o is a copy of an Ndona design with a pair of plain black bands, indicating it originated from Ende. The main ikat bands are decorated with a diagonal lattice that is said to be similar to a fishing net or a bamboo fence made with criss-crossed bamboos.

According to local weavers, the term mangga appears to have no meaning.

Lawo Gelo

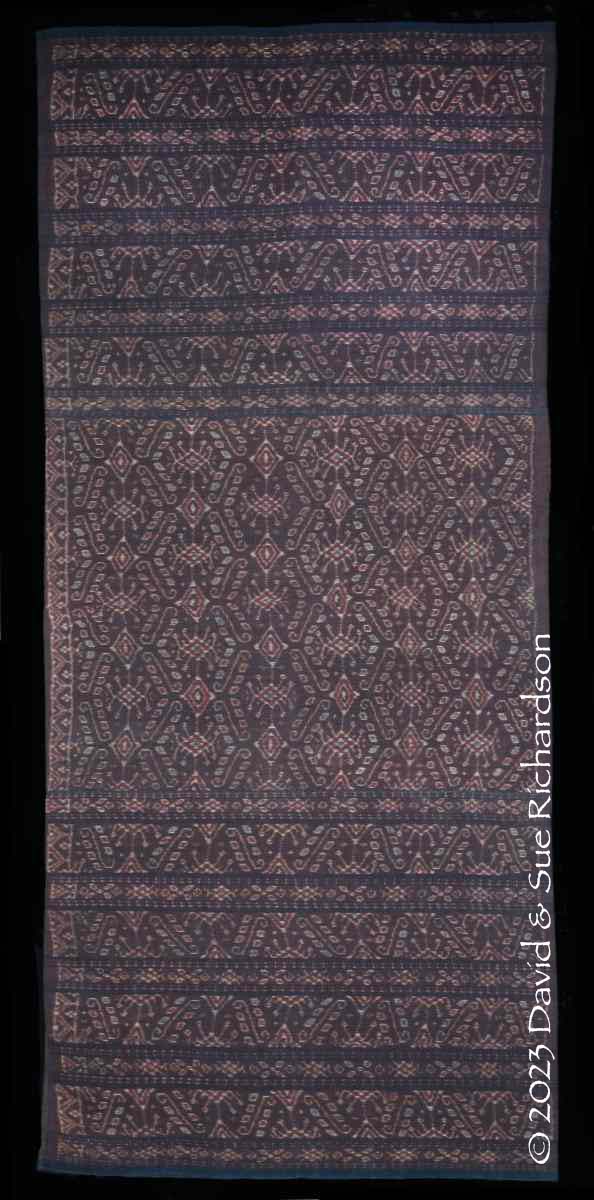

The lawo gelo appears to be a relatively rare design, its pair of black pake mité suggesting an Endenese origin. The following example was woven from commercial cotton that has been synthetically dyed with brown and black.

Above: A lawo gelo woven by Mama Teresia in Nggela in 2011. Size 180cm by 73cm. Richardson Collection. Below: Mama Teresia wearing her lawo gelo in 2013.

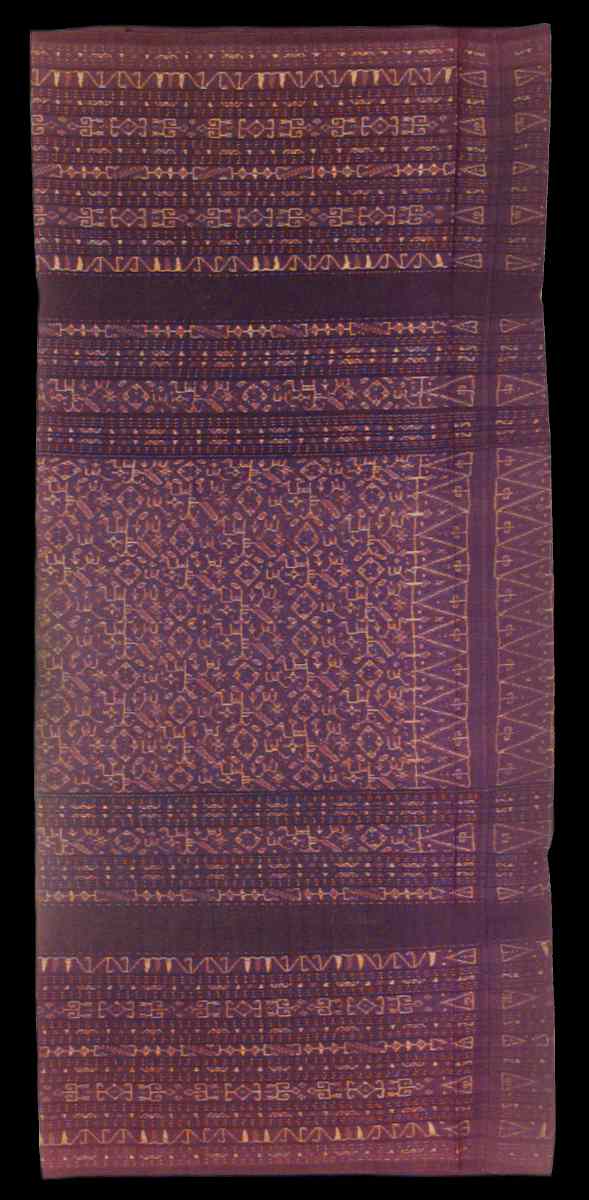

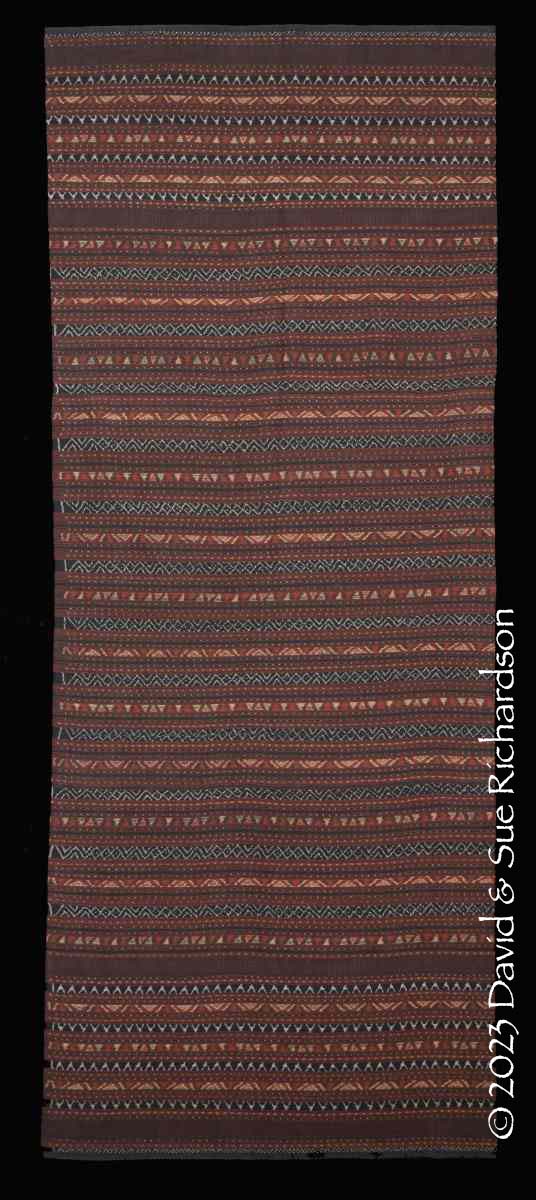

Lawo Kéli Mara Mité

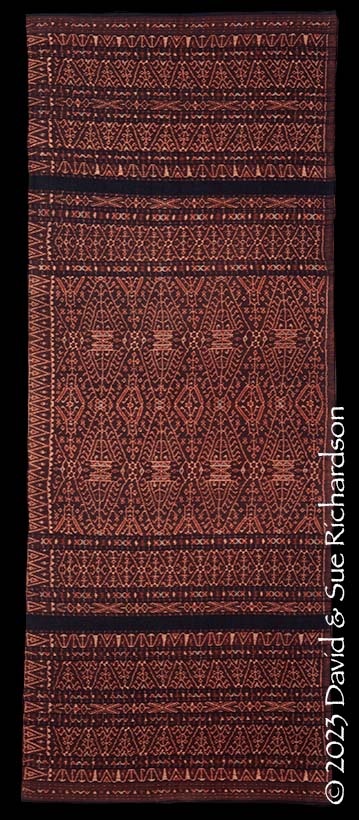

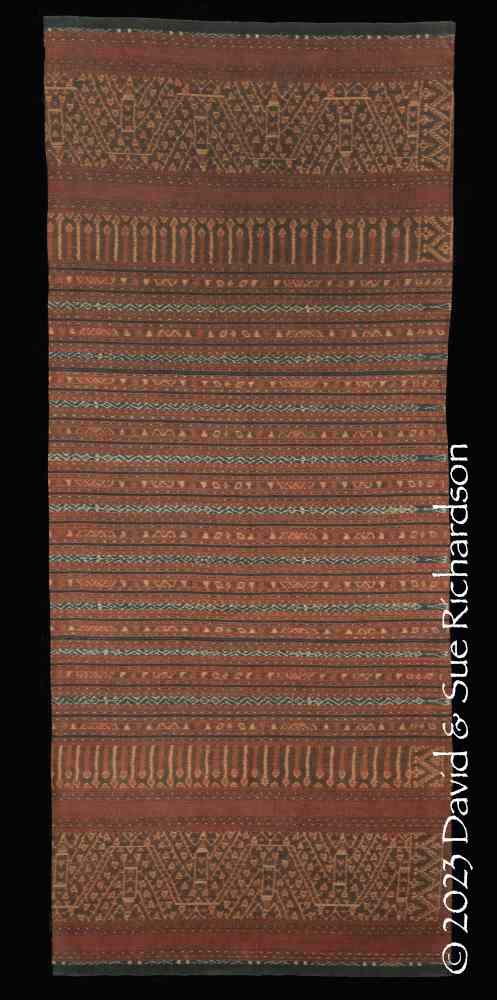

The lawo kéli mara mité has wide end bands decorated with the kéli mara motif and a centre field filled with narrow bands, similar to those used for the lawo gami teresa. The triangular kéli mara motif is composed of a set of truncated pyramids with the spaces in between filled with tiny triangles.

As mentioned above, the kéli mara pattern represents Kéli Mara, a mountain to the northwest of Ende. It has been suggested this was designed in the 1950s by the important weaver Nenek Toja, a Nggela noblewoman who had lived for some time in Ende town. However as already mentioned in relation to the lawo kéli mara té’a, our informant Margarita Gera claims that her late grandmother made a lawo kéli mara when she was a young woman - possibly before the start of the Second World War.

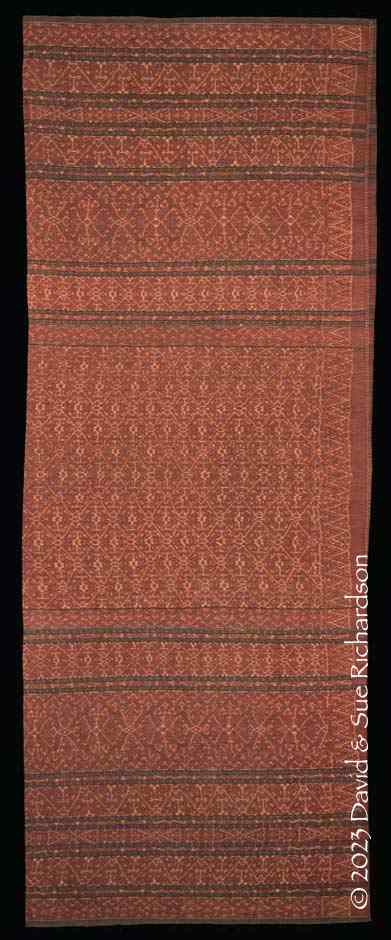

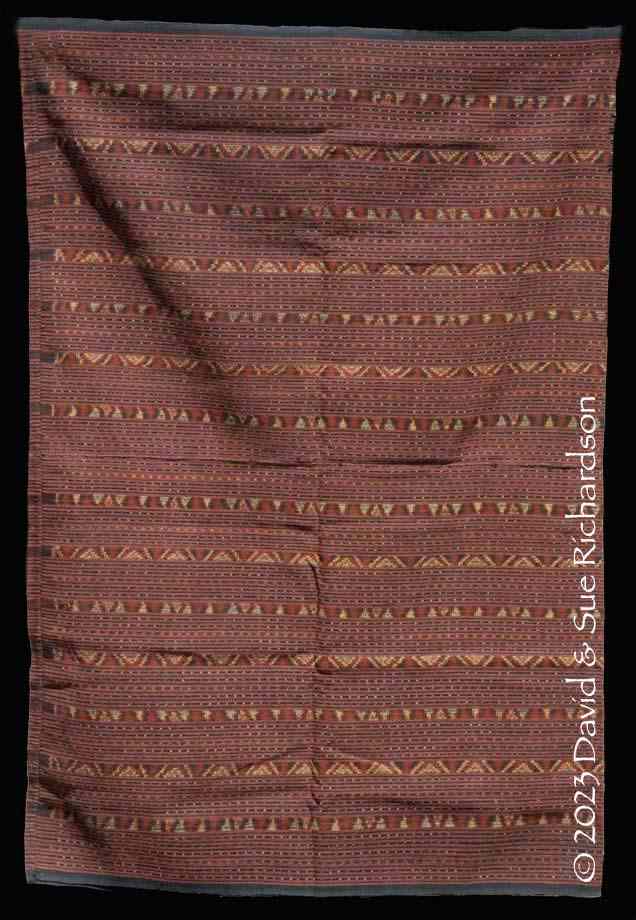

The first example was made in Nggela around 1960 by the grandmother of Fransiska Ngaku. It has a very dark tone compared to other examples.

A fine lawo kéli mara woven in about 1960. Size 148cm by 70cm. Richardson Collection.

Such tubeskirts now enjoy high status, and can be worn by all women for important events and official visits. They also play a significant role in the gawi dance, and are worn under the lawo butu for the ritual rain and fertility mure dance.

The second example was made in 1974 by master weaver Marselina Wéndé, also known as Mama Seli.

A lawo kéli mara mité made in 1974. Size 171cm by 69cm. Richardson Collection.

The third example was also produced by Mama Seli (Marselina Wéndé), this time during the 1990s in Nggela.

A lawo kéli mara mité made in the 1990s. Size 164cm by 69cm. Richardson Collection.

The fourth example was produced in Nggela over an extended period, using machine-spun cotton dyed with indigo and morinda. Maria Goma bound and dyed the yarns in around 1980 and her daughter, Siska Wonga, wove them in 1992.

A lawo kéli mara made by Maria Goma and Siska Wonga over the period 1980 to 1992

De Jong Collection.

The example below was collected by Father Piet Petu SVD, who was born in Nita on Flores and became a priest, lecturer and cultural anthropologist at the Catholic Ledalero Seminary of St. Paulus, just outside of Maumere. In 1983 Father Piet Petu founded the Bikon Blewut Museum, to house his collection of ethnic artefacts, along with the important archaeological collection accumulated by Dr Theodor Verhoeven. Pater Piet Petu managed the museum from 1983 until his death in 1998, during which time he continued to collect ethnic textiles and other cultural items from across Flores and other parts of the archipelago. He left us with a set of albums containing photographs of many of the items in his collection. Five or six years after his death most of these items were sold off by the Seminary to raise funds for a building expansion project.

A lawo kéli mara from the Bikon Blewut Museum, photographed by Father Piet Petu SVD

It is clear from these five examples that in Nggela, the kéli mara pattern is tightly proscribed. However, the fourth example from the Richardson Collection has a slightly modified layout, with a shorter centre field and the main kéli mara band flanked by two narrower ikat bands. It has no provenance, having been collected in Bali in 1996. It may have been made elsewhere in Kecamatan Wolojita in a village such as Jopu, Wolojita or Tenda.

A lawo kéli mara mité made before 1996. Size 159cm by 62cm. Richardson Collection.

The kéli mara pattern remains highly popular up to the present day, but is now almost exclusively made using synthetic dyes.

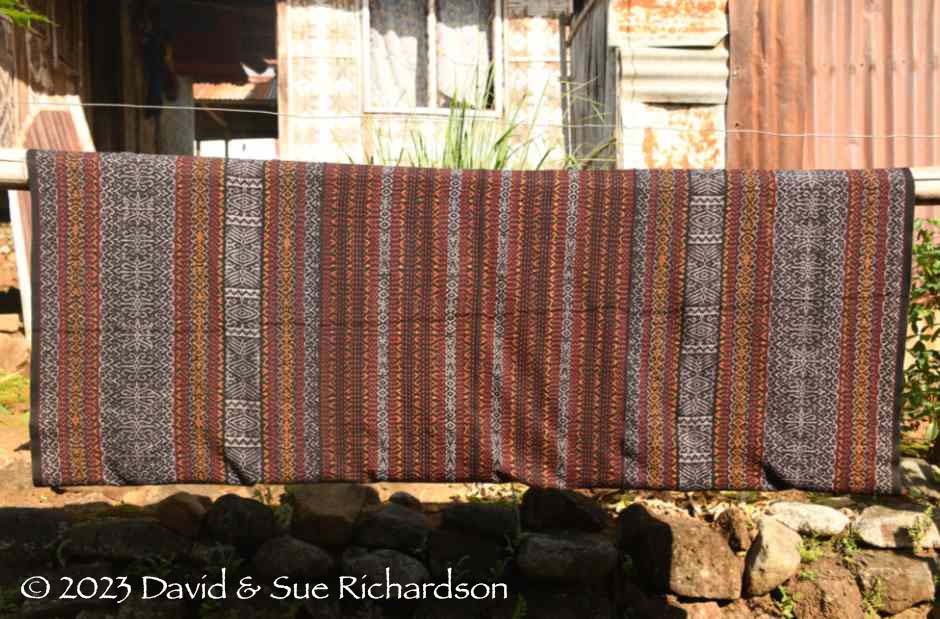

A modern synthetically dyed lawo kéli mara hanging on a line in Nggela

The same pattern is woven in the Mbuli Valley, where it also retains the same nomenclature.

Above: a new chemically-dyed lawo kéli mara produced in the Mbuli Valley

Below: a chemically-dyed lawo kéli mara in Mbuliwaralau Utara

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 21 February 2024.