Asian Textile Studies

Contents

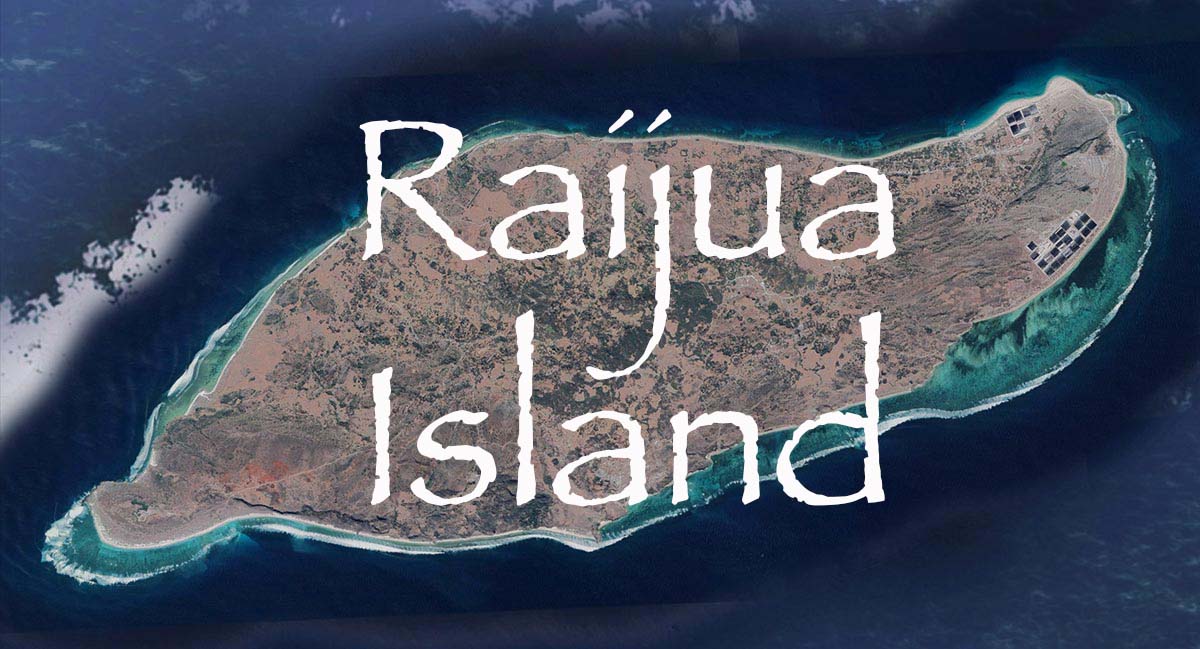

Raijua Island

Geography

Economy

Raijua Beliefs

Archaeology

Oral History

A Brief Colonial History of Raijua

The Indigenous Rulers of Raijua

Social Structure – Udu, Kerogo, Hubi and Wini

Marriage and Bridewealth

Scholarship

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Raijua Island

The beautiful small island of Raijua with its harsh unforgiving landscape has produced some of the most interesting hand-woven textiles in eastern Indonesia, the range and complexity of which appears incomprehensible.

Because of its inaccessibility, the island remains little known and its textiles poorly understood and often misleadingly labelled and described. Further confusion arises because of the close similarities between Savunese and Raijuan culture and some, although not all, of their textiles.

In this webpage we set out to provide a detiled overview of the island and its people and in two sister webpages throw light on some of its traditional textiles and how they were made.

Return to Top

Geography

Physical Geography

Raijua Island lies just west of the larger island of Savu, only separated from its western cape of by the narrow 6km-wide Raijua Strait. Despite this physical closeness, Raijua remains remote and isolated compared to its bigger neighbour.

Raijua Island and the Raijua Strait, as seen from Mesara in western Savu

Located at the confluence of three ocean currents flowing from the Indian Ocean, the Savu Sea and the Sumba Strait, the Raijua Strait can often suffer from dangerous high waves. This creates a major barrier to mobility and has an adverse effect on the economy and health of the local population. In good weather the local ferry boat can sail from Savu’s capital, Seba, to the little port of Namo on Raijua in 2 to 2½ hours, normally departing in the morning when the seas are calmer. However in the rainy season the wave height can reach three to four meters, making the crossing from Savu impossible.

Raijua Island and its larger neighbour Savu

(Image courtesy of the US Army, Washington, D. C.)

Stretching only 13km from Tanjung Ujumahi in the west to Tanjung Beh in the east and just 5km wide, tiny Raijua less than one-tenth the size of Savu. Sadly no detailed map of Raijua yet exists.

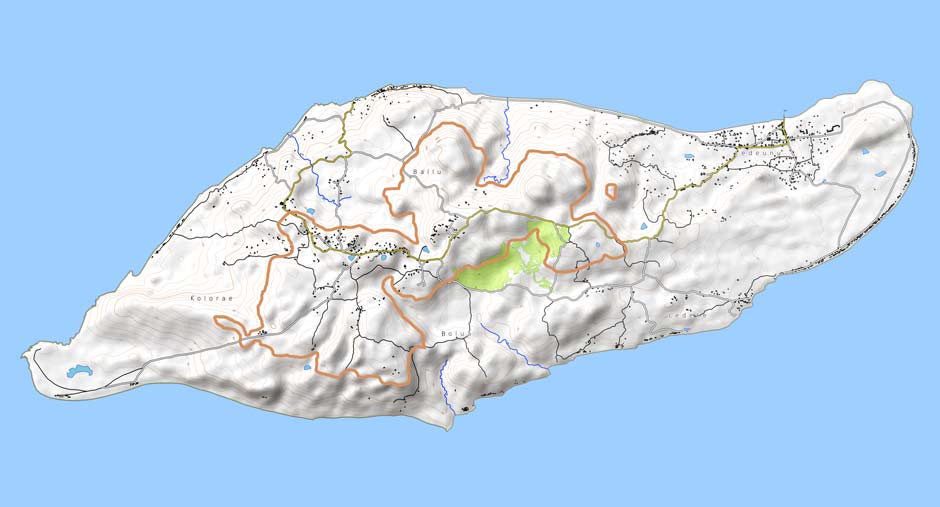

Raijua and some of its many settlements, most of which are tiny

(Image courtesy of Google Earth)

Topographic map of Raijua Island highighting the region enclosed by the 100m contour

(Image courtesy of Elevation Map)

Raijua is a rocky limestone island that is even more lowlying than neighbouring Savu. When Salomon Müller sailed past ‘Randjoea’ in November 1829 he first noted how it was less elevated than Savu (1857, 277). Three quarters of the land is less than 100m above sea level, the highest hills being Lede Wadudagi (170m) in the centre of the island and Lede Ketita (142m) in the southwest. Believers of the local Jingi Tiu religion regard the latter as the most sacred place on the island. The eastern lobe of Raijua is a large expanse of sand, intersected in the middle by a coral ridge.

Sacred Lede Ketita in the southwest of Raijua

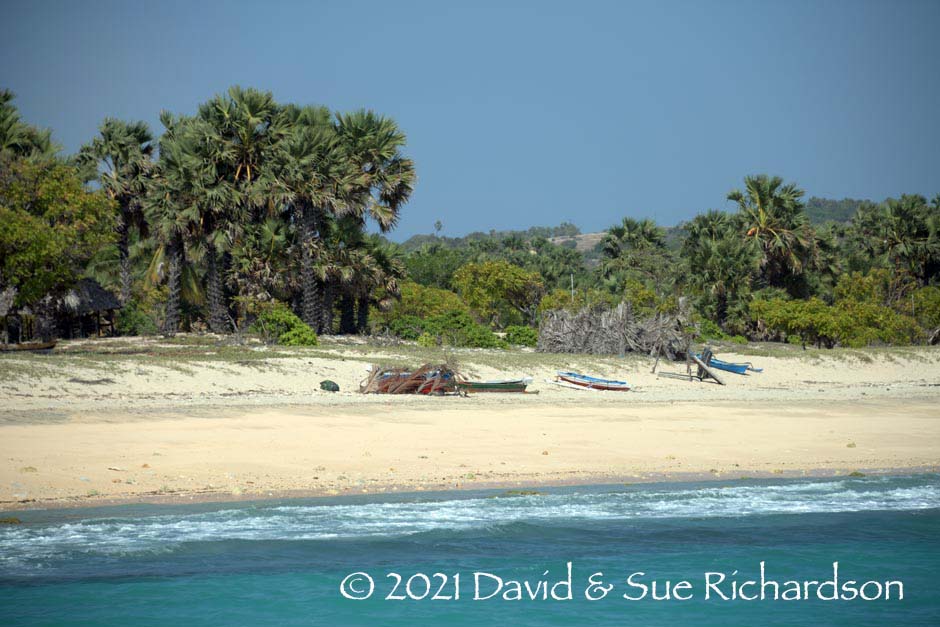

Raijua is surrounded by pristine white beaches, a long coral reef and rich fishing grounds. The reef extends along most of the south and eastern coasts. Work was undertaken in Balu to replant the reef in 2020.

A beach on the north coast of Raijua

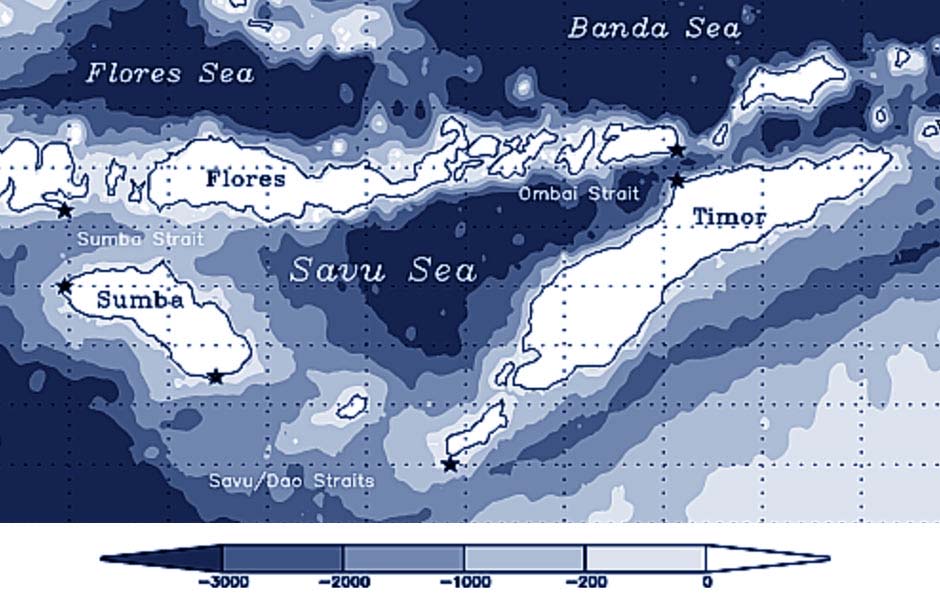

The Indonesian Throughflow is the only tropical pathway that links the global oceans. Here warm waters from the Pacific are cooled by strong air-sea fluxes in the Indonesian seas as they flow out into the Indian Ocean. While one major outflow passes south of Timor Island, the second passes through the Ombai Strait and then between the Savu Strait separating eastern Sumba and Raijua and the Dao Strait separating Dao and Savu. As such Raijua sits on an important marine migration route used by 31 species marine mammal – 18 species of whale, 12 species of dolphin and 1 species of dugong (Mujiyanto et al 2020).

Bathymetry of the seas around Raijua and the Savu and Dao Straits

The dry landscape of Raijua is dominated by palm savannah with open areas of grassland dotted with wooded scrubland, lontar (palmyra) palms (Borassus flabellifer), pine trees and gewang palm (Corypha utan). There is a small amount of coastal mangrove in Kolorae.

Lontar palms and open savannah in eastern Raijua in May, above, and September, below

Climate

The proximity to Australia and lack of hills to catch the rain mean that the climate of Raijua is even more severe than that of Savu, the islanders suffering from a long dry season that lasts from April to November. To make matters worse the wet season can be unpredictable and vulnerable to the El Niño Oscillation. Consequently the number of annual rainy days can vary from 14 to 69. During the short rainy season the west monsoon creates poweful winds which can bring down trees and strip the roofs from houses. In the middle of the dry season (June to August) the east monsoon brings strong dry winds.

The partched landscape of Raijua in May, six months before the beginning of the rainy season

The average air temperature is around 28.5°C, with the highest temperature reaching 32°C in November. The coolest months are June, July and August when the temperature falls to around 25°C.

To highlight the unpredictability of the local climate, during 2020 and early 2021 the island suffered a long drought that lasted from June until February. In March Raijua benefitted from heavy rain and the farmers were happy.

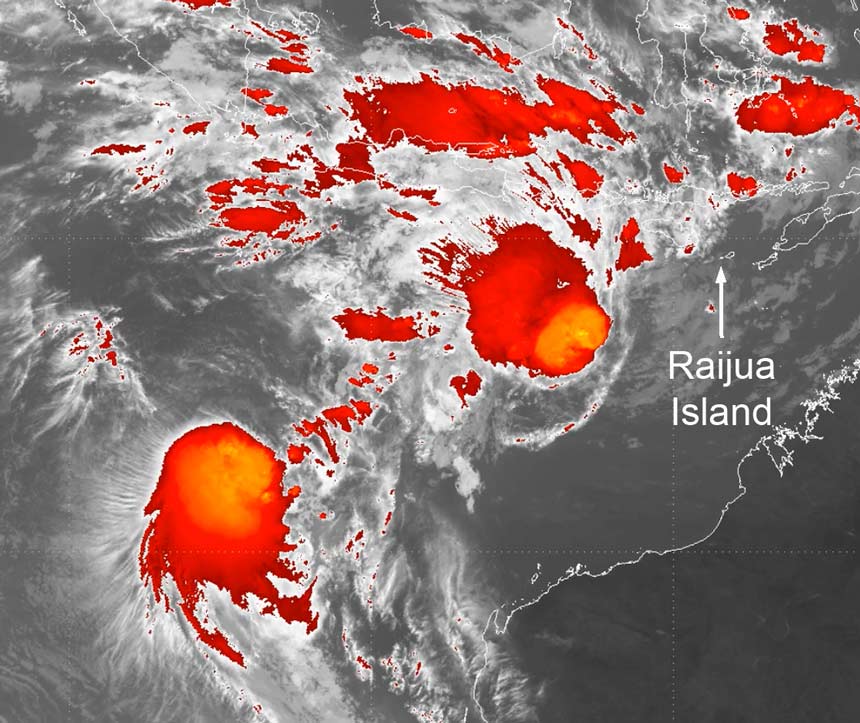

Then in early April, Raijua found itself directly in the path of the deadly Tropical Cyclone Seroja, which tracked westwards from Timor through the Savu Sea and then looped southwards towards the west coast of Australia. Seroja brought torrential rain, which caused flooding, along with devastating 65 mph gusts of wind, which grounded ships, capsized boats, stripped the roofs of houses and toppled lontar palm trees, some of which blocked the roads.

Infrared image of Cyclone Seroja on its way from Raijua to Australia captured by the Japanese weather satellite Himawari-8.

Political

Politically Raijua was formerly grouped with Mahara and Haba within the kecamatan or District of Sabu Barat, administed from the town of Haba in Seba. Sabu Barat was just one of some 35 kecamatan within the kabupaten or Regency of Kupang, administered from Kupang City on Timor.

In order to provide a limited level of autonomy, Raijua was separated from Mehara in 1992 and itself elevated to the status of a kecamatan. Even so, Raijua remained a backwater within Kupang Regency, its poorest and remotest district. The island’s first camat or district head was installed in the same year. He was Elias Susi but was not from Raijua but from the tiny island of Ndao linked to Rote. As a young idealist he was very much opposed to the widespread sexual promiscuity on the island and banned gambling on cockfights. As such he became highly unpopular. In 1995 he was replaced by an official from Savu, who was much more lenient and left the islanders alone to follow their past practices.

The collapse of the Suharto regime in May 1998 led to the realisation among the ruling elite that a vast archipelago like Indonesia could not be governed from Jakarta. The new national government embarked on a policy to decentralise government and in 2001 introduced legislation to increase regional autonomy. However this was not focussed on empowering the provinces but on the sub-provincial administrations instead. This led to large Regencies becoming fragmented into smaller Regencies.

Kupang Regency was first to be slimmed down in 2002, with Rote and Ndao split off as a separate Regency. It was not until 2008 that the Savu islands followed suit to become Sabu Raijua Regency. The hope was that given its own autonomus administration the development of local infrastucture would be a accelerated. However the new local government soon saw its priorities elsewhere and in 2016 the Regent (bupati) was arrested for corruption and in the following year jailed.

Kecematan Raijua is administered by a camat or district head whose office is located close to Namo port by Ledeunu. He reports to the current bupati of Kabupaten Sabu Raijua.

The Camat of Raijua, Titus B. Duri

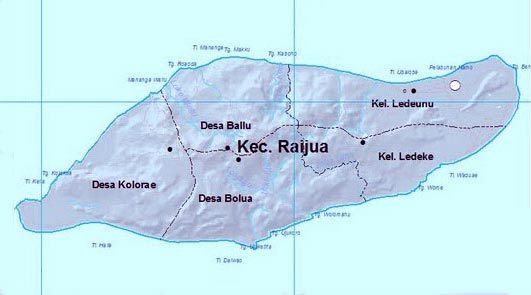

Kecematan Raijua is divided into two kelurahan (urban villages), namely Kelurahan Ledeunu and Keurahan Ledeke, and three desa: Bolua, Ballu and westernmost Kolorae.

Village areas (desa) on Raijua Island

Each of the five desas is split into five dusun (sub-villages), making 25 dusun in total.

Until 1918 Raijua was led by its own Raja based in the main settlement of Udju Dima, which has since become Ledeunu. Today Udju Dima is the small royal enclosure located to the south of Ledeunu.

Inside the royal enclosure of Udju Dima

Population

Despite its unforgiving climate, Raijua supports a population just over 10,000, giving it a higher population density that Savu.

Population and Households in 2019

| Village | Main Hamlet | Population | Households | ||

| Men | Women | Total | |||

| Kolorae | Lupe | 857 | 915 | 1,772 | 467 |

| Bolua | Pad'a Lebba | 1,107 | 1,064 | 2,171 | 553 |

| Ledeke | Ledeke | 683 | 628 | 1,311 | 349 |

| Ledeunu | Eireka | 1,713 | 1,574 | 3,287 | 787 |

| Ballu | Daidamu | 852 | 820 | 1,672 | 401 |

| Raijua | 5,212 | 5,001 | 10,213 | 2,557 | |

(Kecamatan Raijua Dalam Angka 2020, 13)

Almost half of the population was aged 19 or less (BPS Kabupaten Kupang 2019). Almost one third of the population live in the largest kampong of Ledeunu.

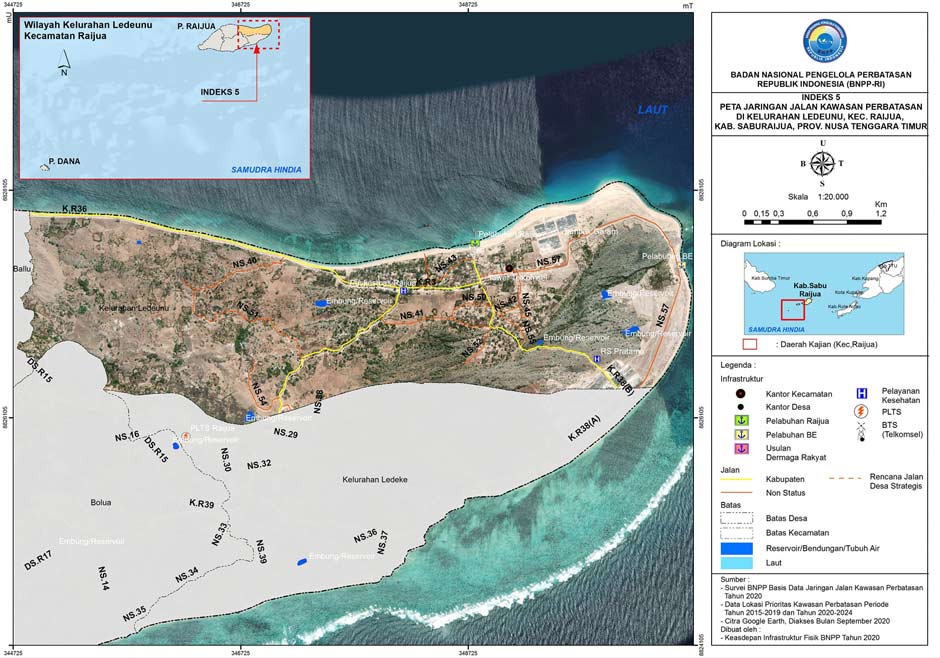

Infrastructure

Raijua is a highly undeveloped island and has only recently benefitted from a modicome of infrastructure investment.

In the past water availability was a major problem during the dry season. To alleviate the risk of drought the government has in recent years constructed seven small water reservoirs (embungs) on the island for crop irrigation. Two more are planned.

Raijua does have an adequate medical clinic as well as 9 kindergarten, 7 primary schools (sekolah dasar, SD), 2 junior schools (sekolah lanjutan tingkat pertama, SLTP) and 1 high school (sekolah menengah atas, SMA). Two now have internet access (Portal Geospasial, Sabu Raijua). However the quality of education is poor, not helped by the fact that many children do not go to school because they have to help their parents at home. In 2020 a local teacher reported that it was commonplace for children in primary schools grades 3 or 4 to still be unable to read (Fernando 2020).

Prior to 2013, only those few homes with diesel generators or small domestic solar panels had their own supply of electricity. However that year a new solar power plant (Pembangkit Listrik Tenaga Surya or PLTS) became operational, constructed with an array of 54 large solar panels to the west of Ledeke. This provided electricity to the entire island for 24 hours daily, but soon encountered technical problems in 2014 leading to rolling blackouts.

The solar power station in the centre of the island

These have since been resolved so there is now a regular electricity supply on Raijua operating 24 hours a day, but this can still sometimes be unreliable.

Today 276 households have a satellite dish feeding a TV set (BPS 2020).

In the recent past the condition and width of the coastal road prevented access by 4WD cars and trucks. Following road improvements in May 2015 vehicles can now pass, although the road remains rocky and becomes inaccessible durong the rainy season. By 2019 there were officially 11.4km of surfaced roads (mostly in Ledeunu and Ledeke) and another 29.7 of ‘paved’ roads. This makes it appear as though the road system is much better than it really is. To reach Kolorae from Ledeunu on motorbike via the coastal road takes around 45-60 minutes.

The concrete road from Ledeunu to Ledeke built in 2015

The gravel road in Kolorae leading down to Tanjung Ujumahi

In 2019 a major project commenced to upgrade 5km of local roads, working outwards from Ledeunu.

The planned road system for Raijua

In 2019 there were 28 pick-up vehicles on the island and 14 trucks.

The main port of Namo (formerly Budae) at Ledeunu can dock the larger ferries from Kupang and Ende as well as motorboats from Seba. Originally built in the 1980s it was badly damaged by heavy seas in January 2017 and has since been repaired (Antaranews 2018). There are also two local harbours: Menanga in Ballu, heavily used by local seaweed farmers, and Ei Bego (or Ai Bego) in Kolorae, used by fishing boats from Sumba.

The small port of Namo just east of Ledeunu

Work has now started on the construction of a new harbour at Tanjung Beh on the eastern tip of the island, which is better located for the rainy season.

Until recently there was no telecommmunication tower on the island to service those residents who owned cell phones, so people had to climb ‘signal hill’ or go to the harbour at Namo to obtain an unreliable link to the mainland mast at Mesara. In 2013 a small signal amplifier was placed on the island but was damaged in the following year. It was only in 2019 that a small telecoms tower was erected close to Namo.

The new Telkomsel tower at Namo harbour

Economy

Because of its harsh environment Raijua is one of the most impoverished regions of Indonesia, with almost every citizen classified as poor. Roughly 40% of children are underweight.

In the past Raijuans suffered from an unrelaible food supply and even worse nutrition. Due to the extremely dry weather the majority of the land is unsuitable for farming and, apart from in a few tiny areas, rice cultivation is completely impossible. Consequently Raijua was known as ‘the island of non-eating people’ (Kagiya 2010, 9). The small harvest of sorghums and mung beans only lasted for four months so the islanders survived on a staple of gula Sabu, the thick syrup obtained by boiling the sap of the lontar palm. This was either dissolved in water or drunk as the fresh sap. Men harvested the sap in the mornings and evenings, climbing around 10 to 15 trees, while the women collected the firewood and boiled the syrup. The people of Savu, Rote and Ndao followed the same lontar palm economy (Fox 1977).

Since 1997 palm tapping has almost died out as many villagers along the west and southeast coasts have turned to more profitable seaweed farming. Today gula Sabu is imported from the main island.

As already mentioned water is a scarce resource on Raijua. Although there are several small fresh springs at Menanga in desa Bellu and Loborawo in desa Bolua in the western part of the island, it takes hours to fill just one tanker. Consequently most drinking water is shipped to the island by sea.

Rice cultivation on Raijua is virtually impossible because of the extremely dry conditions. The Indonesian Navy set up a project to attempt to cultivate rice on the island but it ended in failure. In recent years the government of NTT have provided support in the form of heavily discounted, low quality imported rice although adverse sea conditions can often disrupt supplies. This is shipped from Seba to Namo on two local supply boats owned by a Sabu Raijua aid agency – the Pulau Dana Satu and the Pulau Dana Dua. They return to Seba with Raijuan seaweed.

The Pulau Dana Dua unloading sacks of rice at Namo

Today the main Raijua food crops are still sorghum and mung beans supplemented by some millet. Maize will grow on Raijua but will not form cobs, so is only planted for animal feed. Sorghum was an important traditional crop throughout much of eastern Indonesia but died out on islands like Flores in the face of government pressure to plant rice. Although it is more labour intensive to farm than rice and maize, it requires less water so is an ideal crop for Raijua.

Nevertheless there has been a small amount of rice grown on Raijua. There are nearly twenty tiny paddy fields dedicated to Banni Kedo located in fertile areas close to wells. In the recent past many have fallen into disuse because of dry weather. The largest, about one hectare in area, is at Daihuli in desa Bolua in Upper Raijua. It is farmed by about 20 people and is harvested twice a year.

A small sorghum field long after the harvest

The majority of Raijuans are involved in some form of agriculture, whether growing crops, harvesting seaweed or raising livestock. A survey of Bolua in 2018-19 found that out of a population of 1,003, 893 were farmers (split almost evenly between sexes) and 60 were livestock breeders (Bolua village office, 2018). The rest were civil servants, teachers and traders.

For an island with a surface area of 3,816ha, there is 1,281ha of dryland available for cultivation. In 2018 the productive cultivated areas by crop were as follows:

| Hectares (100m²) | 2016 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Sorghum | 691 | 652 | 456 |

| Mungbean | 345 | 418 | na |

| Coconuts | 44 | na | 39 |

| Maize | na | 23 | na |

| Lontar palm | 17 | na | 21 |

| Cashew | na | 14 | na |

| Millet | na | na | na |

(BPS Statisik Kabupaten Kupang 2017 and 2019)

Raijua also harvested 82.5 tonnes of mustard greens in 2018.

In recent years the livestock census reported:

| 2018 | 2019 | |

| Chickens | 22,013 | na |

| Goats | 8,493 | 9,342 |

| Pigs | 6,784 | 7,802 |

| Sheep | 3,152 | 3,814 |

| Horses | 1,739 | 1,861 |

| Buffalo | 665 | 712 |

| Cows | 29 | 31 |

(BPS Statisik Kabupaten Kupang 2017 and 2019)

Despite being surrounded by pristine seas, fishing is not a major activity. In 2019 there were 74 full time fishermen (all based in Ledeunu) and 298 part-time fishermen catching flying fish, nipi, sardine, snapper and Pacific mackerel. The total catch was 149 tonnes in 2018 and 187 tonnes in 2019. In 2010 the NTT government created the Sabu Raijua Marine Park to conserve the local marine life. Whilst traditional fishing is still permitted around the coastal areas of Raijua, large segments of ocean to the north and southwest of Raijua have been designated ‘no-take’ zones.

Up until the 1990s the only cash generating industry on Raijua was limited to the weaving of pandanus tikar mats, and the production of turtleshell and black coral jewellery (Harkness 2020). In 1997 or 1998 the islanders began to farm seaweed, which thanks to the clean surrounding waters is extremely high quality. Seaweed farming is a labour-intensive cottage industry that involves the whole family and is ideally suited for islands with extensive flat sandy beaches and shallow waters like Raijua and Savu. Over the past two decades the industry has grown rapidly. By 2011 some 2,577 seaweed farmers from 514 households were producing 2,743 tons (Kementerian Perhubungan NTT 2019). Since then the number of farmers has remained static but their productivity has increased. In 2019 there were 2,419 seaweed farmers (658 in Ledeunu, 590 in Bolua and 411 in Kolorae) producing 6,982 tons (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Kupang, 2020).

A seaweed farmers beach shack, Raijua

In eastern Raijua the seaweed farmers have built small ramshackle shelters where they can rest and eat, which stretch for almost 3km along the beach. Seedlings are tied to ropes that are staked below the surface and which take about 45 days to mature. When the seaweed is harvested, a small branch is snapped off and retied to the rope as a new seedling. The harvested seaweed is dried on crude home-made racks that line the beach. The dried seaweed is then shipped to Seba where it is processed into dried seaweed chips. Seaweed has a high economic value being used for the extraction of agar and carrageenan, important ingredients for the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries.

Seaweed drying racks at Tanjung Beh

Another new Raijuan industry is solar powered salt extraction. In the past salt production was a cottage industry with local people evaporating sea water in small lontar palm leaf baskets and clam shells. The Bogor Agricultural Institute discovered that Raijuan salt is very good quality, containing a high level of iodine. Between 2011 and 2018 the local Sabu Raijua government constructed 107 hectares of salt ponds employing geomembrane technology, the crystallization pond bed being covered with low permeability plastic sheeting to ensure salt cleanliness. The ponds are manually harvested using long-handled rubber scrapers at least three or four times a month, although activity ceases during the monsoon season. Annual production was 4,815 tonnes in 2018. The target is to expand capacity to an area of 400 ha (Wiendiyati et al 2020, 270).

The concrete salt drying ponds and storage sheds at Tanjung Beh

Manually harvesting salt in bare feet

Salt is first shipped to Seba and then onwards to Surabaya, Makassar and Pontianak.

Thanks to seaweed and salt the standard of living on Raijua has improved markedly in recent years, with families becoming more prosperous and living in better houses.

Return to Top

Raijua Beliefs

Raijuans speak Savunese and are mainly Protestant, although a significant minority retain their beliefs in the ancient religion of Raijua (and Savu) called Jingi Tiu.

According to Kagiya, on Raijua, Jingi Tui means ‘servant of devils’, the devils being Marega and Banni Kedo, the two female ancestors who introduced many of the rules governing the moeties of hubi ae and hubi iki (2010, 68). It has been previosly suggested that it is a term of Portuguese origin meaning pagan god. However it has been recently pointed out that on Savu its meaning is far less clear, the Savunese word jingi meaning to destroy or pillage (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 2).

Jingi Tiu is a complex system of beliefs that is basically ancestor-based. Some have incorrectly described it as animist (perceiving things as animated and alive).

Jingi tiu rituals are held for the well-being of the population, for connecting people with their ancestors (and through them to God) and asking for fertility for humans, animals and plants as well as for rain and a good harvest. Offerings are placed on pillars of the house and on specific stones while reciting a sacred text.

Jingi Tiu is administered by a council of priests, the Mone Ama, membership of which is hereditary and restricted to one single male clan (udu) or combination of clans, priesthoods being passed from father to son or from brother to brother. Every priest has to be married because his wife also has important religious responsibilities. Together the Mone Ama holds the complex secret knowledge about the creation of the world and the genealogies of the early ancestors. The Mone Ama also fulfilled the role of the court of customary law.

In 1982, 60% of the population followed Jingi Tiu but this had decreased to around 25% in 2010 while the proportion converted to Protestantism had increased (Kagiya 2010, 19).

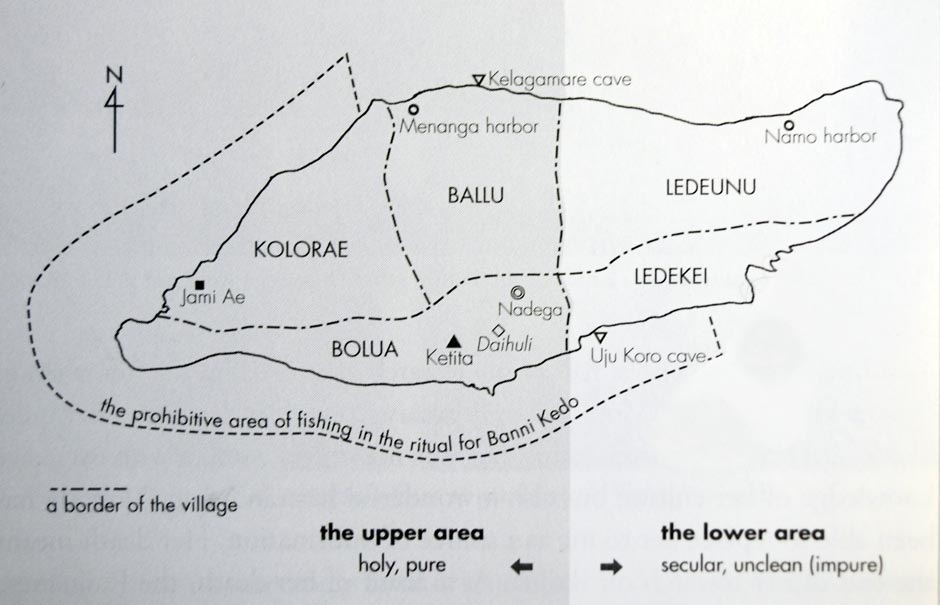

Kagiya found that Bolua had the largest number of Jingi Tiu followers and was followed by Kolorae (2010, 19). The western desas of Bolua, Kolorae and Ballu are grouped in the upper area called Raijua Dida, that is considered holy and pure, while Ledeunu and Ledeki are in the lower area called Raijua Wawa that is considered secular and impure.

Map of the pure and impure zones of Raijua, showing Daihuli and Uju Koro, the holy land and the residence of Banni Kedo; Kelagamare, the residence of Marega; and the holy ‘mountain’ of Ketita. From Kagiya 2010.

A survey by the NTT Provincial Government in Kupang in 2012 found that 74% of the population were Protestant, 23% Jingi Tiu and 3% Catholic (Roland et al 2016, 30). A later 2015 survey in Kolorae found that 68% of the population were Protestant, 8% Catholic and 25% Jingi Tiu or other.

According to official local government figures for 2019, 84.3% of the population were now Protestant, 8.4% Catholic, 0.3% Muslim and 7.0% classified as ‘other’. However it is likely that people were unwilling to decalre to a government body that they belonged to an unoffical religion like Jingi Tiu.

Today there are 14 protestant places of worship on the island, 6 of which are in Ledeunu, and 2 Catholic churches.

One of the six Protestant churches in Ledeunu

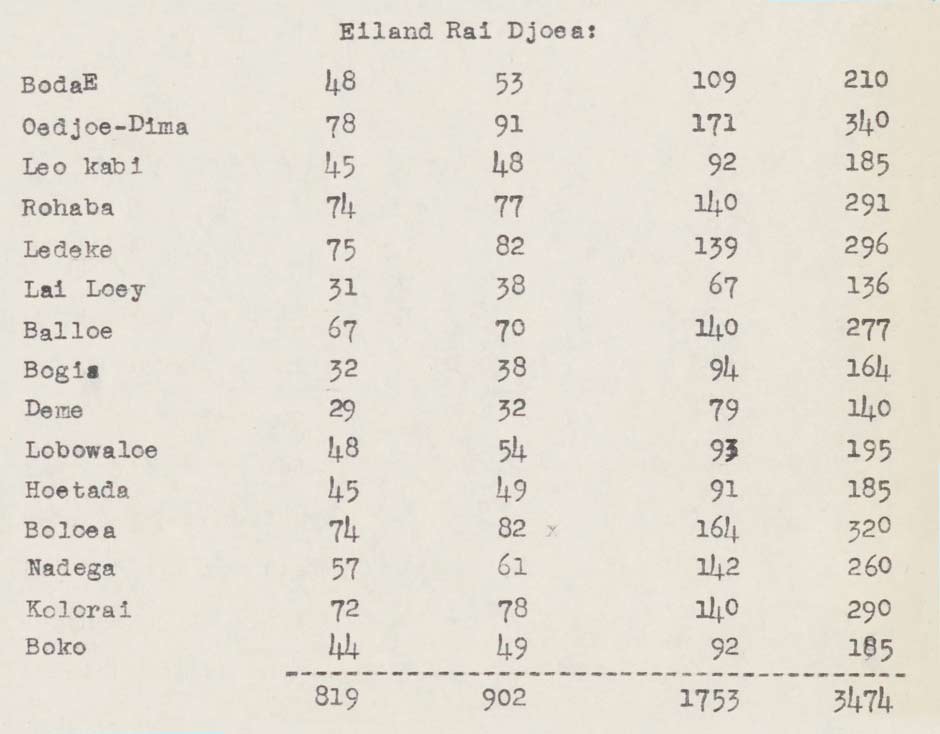

The simple church at Ledeke

Return to Top

Archaelogy

The archaeology of Raijua is yet to be studied and could be revealing. Preliminary work on Savu has identified signs of Paleolithic activity around various rivers and of Neolithic remains in caves (Intan 2016).

In 1984 Soejono and Sartono discovered that Palaeolithic tools were abundant on river terraces located in the northern area of Savu (Jatmiko 2010, 21-30; Jatmiko 2014). The finds included axes, chopping-tools, chisels, core tools and flakes made from silicified limestone. Research undertaken by the Arkenas Research Center in 2010 confirmed the Palaeolithic finds and documented a number of river sites. They concluded that there was considerable potential for further discoveries on the island.

The presence of Palaeolithic tools point to the existance of a Melanesian population on the islands prior to the later arrival of Austronesians - at some time during the past few millennia.

Return to Top

Oral History

The Savunese regard the domain or rai of Raijua as being of special importance compared to the five rai on the mainland, believing it to be where the culture of Savu originated. Nico Kana explained that the close bond between Raijua and Savu was based on the belief that the rai of Raijua was central whereas those of Savu were peripheral (1983, 117). Fox has argued that native legends suggest that the transition from swidden cultivation to a lontar palm tapping economy began on Raijua before spreading to Savu, Ndao and Rote (1977, 52). This seems questionable as it is hard to envisage a community surviving on Raijua on just swidden cultivation alone.

Like Savu, Raijua is an island lacking any indigenous history. Its people were illiterate prior to the establishement of the first schools in the early twentieth century. Even then the Raijuans resisted western education and religion. Instead their past was memorised over scores of generations in the form of mythical narratives by members of the Mone Ama.

Raijua abounds with a plethora of these mythical tales and stories, some of which relate to the origin of the Raijuan people and their customs. To complicate matters further, there are different versions of the same stories. Akiko Kagiya has attempted to put forward a coherent summary of some the founding myths (2010, 46-50). There are also complex narratives describing the origin of the people of Savu that were first gathered on the island by Mattheas Teffer in the 1870s but were more recently analysed in great depth by Geneviève Duggan (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018). Whilst the Raijuan and Savunese accounts share many common features, the two sets of narratives do not precisely dovetail together, suggesting that with repeated telling they have gradually drifted apart. Even so, it is clear that Raijua and Savu share a common heritage.

Kika Ga and Hawu Ga

Kagiya makes no mention of the mythical figures Kika Ga and Hawu Ga. However some writers have documented a narrative in which Kika Ga and his younger brother Hawu Ga sailed from the west to reach Raijua before continuing on to Savu. In one version they first made landfall at Cape Sasar, the northern tip of Sumba Island. They then continued their journey east and landed at Jawawawa on Raijua. Kika Ga stayed on Raijua but Hawu Ga sailed on to reach Savu (Widyatmika et al 1982, 69-70). At that time there was no complete island of Savu, just two mountains, Lede Kebuhu and Lede Perihi. Because Hawu Ga did not return to Raijua, his brother set out to find him, landing at Penjara Mea, a promontory on the south coast of Savu in the present day district of Liae.

In 1876 the missionary Mattheas Teffer reported that both the Raijuans and the Savunese believed that they were all descended from one common ancestor named Kieka, who was the first resident of ‘Randjoewa’ (Teffer 1876, 351). The elderly residents of Savu said ‘We all come from Randjoewa’.

Teffer claimed that he conducted ‘very lengthy research’ to obtain an exact version of the oral history of the population of Savu. The descendants of Kieka (Kika Ga) remained on Raijua for seven generations before coming into contact with Savu. Following a family dispute, Ngara Rai, one of Kika Ga’s descendents, and his wife crossed to Savu. The Savunese were welcoming, so they felt no need to return to Raijua. Savu was already populated and divided into nine kampongs, each headed by a chieftan. The people were peaceable and industrious and had learned how to manage the barren landscape, diverting what little water was available to moisten the fields.

According to the Savu narratives collected by Duggan, Kika Ga was Savu’s very first male ancestor (recorded in the extensive genealogies), who arrived from the far west shortly after the island had been flooded (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 20). These stories also say that at that time Savu consisted of just two unconnected mountains: Merèbu and Kebuhu. However this rendition differs from the Raijuan narratives by indicating that Kika Ga landed not on Raijua but at Wadu Mea (Red Rock) at the foot of Mount Merèbu, which today lies in the district of Liae. Kika Ga married and settled on Mount Merèbu, later excavating land from Raijua to connect Merèbu and Kebuhu, thus creating the complete island of Savu.

Today they perform the hole thanksgiving ceremony on Savu in which they symbolically return land to Raijua by placing soil in a tiny perahu and launching it towards that island.

Belodo and Jawi Rai

The first Raijuan myth of origin begins with Pulodo, the heavenly God, who had three daughters (Kagiya 2010, 45-48). The youngest, Belodo, cooked food that could never be fully consumed no matter how much was eaten. Her father therefore thought that she was a witch and sent her down to earth, accompanied by a fly, a mosquito and fire (Kagiya 2010, 47). When she arrived she transformed herself into a wild pig and met Rai Ae and his son Jawi Rai. They lived in a cave and did not yet know how to use fire. Belodo did and while they were away in the forest she secretly cooked some food stored in their cave. They returned and ate the food, which was colourful and delicious. They decided they needed to find the cook and returned to the forest where they saw a pig turn into a beautiful woman and begin cooking. They caught Belodo and removed her pig’s skin by force.

Rai Ae and his son then fought over the beautiful Belodo and Jawi Rai was killed. Belodo was upset and went to his grave and revived him. Belodo, a daughter of God, and Jawi Rai, an earthly Raijuan, joined in marriage and had two children – Raga Rai and Opo Rai. The latter would never stop crying and Jawi Rai was irritated, saying she was born from the belly of a pig that was also a witch. Belodo was offended and returned to heaven with Opo Rai. Later Jawi Rai went to heaven to find Belodo and Opo Rai, overcoming many trials. He finally found Belodo and they had four more children.

The heavenly God allowed Belodo to return to earth with all kinds of seeds with the one exception of rice. However Belodo had hidden a grain of rice in her hair so was able to bring rice into the world. Later two of her children in heaven brought her the seeds of the lontar palm. Back on earth Belodo had two more children, a son Ngara Rai and a daughter Piga Rai, who eventually married each other, committing the very first act of incest.

In the Savunese version of this story, Be Lod’o (‘Be from the sky’) married Rai Ae, a great-great-grandson of Kika Ga. They had a son, Ngara Rai, and a daughter, Piga Rai, who also had an incestuous relationship (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 21).

Hawu Miha and Babo Miha

A second set of stories concern Hawu Miha and his younger sister Babo Miha. They were the grandchildren of Ngara Rai and Piga Rai and just like their grandparents became husband and wife through an incestuous marriage. They are considered the founding ancestors of the Raijuans (Kagiya 2010, 59 and 79).

They had two daughters, Muji Babo and Lou Babo, named after their mother because they believed that if the name of the child was the same as the island Hawu (Savu) it would not be healthy (Kagiya 2010, 25).

One day Babo Miha left the island by sea to travel to a far away country. Many years later Hawu Miha wondered what had become of his sister and her descendants so called out to heir souls and planted sorghum and green grams every year, praying that they would have enough food. Raijuans believe that Babo Miha is always in the place where the sun sets, i.e. in the west.

Muji Babo and Lou Babo

Hawu Miha and Babo Miha’s daughters Muji Babo, the elder, and Lou Babo, the younger, lived some 42 generations ago. Muji Babo established the aristocratic female clan or moiety hubi ae, while Lou Babo founded the moiety of commoners called hubi iki. However wini sub-clans did not yet exist at this time.

One day they had an argument as to which was the best weaver and decided to settle it by holding a competition. Muji Babo took the thin indigo from the top of the indigo dye pot but Muji Babo took the thick paste from the lower part of the dye pot. Because of this legend, the colour of the seam or bakka that joins the two panels of the sarong identify which hubi a woman belongs to – red for hubi ae and black for hubi iki. According to Kagiya (2010, 218):

The foundation of Raijua’s culture of cloth was established during the Muji Babo and Lou Babo era.

Marega and Banni Kedo

A third set of narratives revolve around a prominent figure named Maja Pahi, who arrived on Raijua as an outsider, and two women – Marega and Banni Kedo, two powerful witches who had a profound influence on the two female moieties, hubi ae and hubi iki. Oral genealogies suggest that they may not have been mythical people but real ancestresses who lived on Raijua 15 generations ago – a time roughly falling within the seventeenth century.

There are many stories about Banni Kedo, who is depicted as a lower-class woman of uncertain descent, the child of an incestuous brother and sister. Ashamed of his incestuous relationship, Banni Kedo’s father threw her and her mother overboard into the sea while on a voyage, but Banni Kedo survived and swam to shore. As a result of many marriages and prolific adulterous relationships, the abandoned daughter went on to have many children, establishing many of the rules associated with the ritual use of textiles in the moiety hubi iki. She was a social climber who told the island’s women that they should only share a bed with rich noblemen (Kagiya 2010, 37). Banni Kedo was also cruel and violent, killing the men who refused her.

At some stage she had a relationship with Maja Pahi. In some stories they are friends, in others a sister and younger brother.

Marega or Mare Gha was a contemporary and friend of Banni Kedo but unlike Banni Kedo was an aristocrat. She was a daughter of the King or God of the Sea, Ama Lado Ga, and had a brother called Lado Ga. She also had many children as a result of three marriages and was responsible for establishing many of the rules associated with the ritual use of textiles in the aristocratic moiety hubi ae. Marega is worshiped on Raijua as the ancestress who passed down the technical skills of dyeing and weaving to her descendants.

Raijuan women believe that Banni Kedo and Marega were responsible for introducing the extremely complex and meticulous rules covering every aspect related to the production and use of textiles (Kagiya 2010, 93). These rules even lay down the elaborate procedure to be followed following the theft of cloth.

The stories about Raijua’s powerful female ancestors underpin the local belief that a sister should always be paired with her brother, especially her younger brother (Kagiya 2010, 69). Furthermore a sister is seen as having spiritual predominance and patronage over her brothers throughout their life.

Maja Pahi

According to Kagiya, in most stories Maja is the younger brother of Banni Kedo, but in others they are either friends or husband and wife who came to Raijua together Kagiya 2010, 78). He is sometimes referred to as Maja Pai or Maja Pahi (Kana 1983, 40, 117).

Like Banni Kedo, it is not known where he came from or when he first arrived on Savu. Before he arrived on Raijua the island was ruled by Mone Weo. Maja fought with Mone Weo and forced him to leave the island (Kagiya 2010, 78). However it is not clear whether Maja was a ruler of either Raijua or Savu. Maja lived on Ketita, Raijua’s sacred mountain.

On Raijua, Maja is still considered a powerful male ancestor. Today the people of Raijua call themselves Niki Maja or warriors of Maja, legitimate citizens of the land of Maja.

Many writers have made the connection between Maja Pahi and the powerful Javanese maritime empire of Majapahit, which thrived from 1293 to around 1500. Ten Kate was of the opinion that the arrival of ‘Javanese vagrants’ had contributed a Hindu element to their ethnicity but had left no lasting influence on their culture (1894, 697). In his view the islands had probably already been populated from Timor, Rote, Ende, Buton and South Sulawesi. Van der Wetring thought that Majapahit was the ancestor of the Savunese (1926, 486). More recently Nico Kana has made the same historical link to local narratives (1983, 71-72). Some Raijuans not only believe that Gajah Mada, the Majapahit commander who conquered the islands east of Bali, settled on Raijua, but died in the village of Ketita. The problem is that Savu is not specifically listed among the kingdoms subordinated under the Majahpahit Empire in the Nāgara-Kěrtāgama, composed on Bali in 1365, although it does list Sumba. Given the extensive eastern island territories temporarily subjugated by Gaja Mada, it is not inconceivable that his fleet once visited Savu and perhaps even Raijua on their way to Sumba.

Several features on Raijua are still associated with the Majapahit prime minister. A cavity in a coral outcrop containing water near Ledeunu is claimed to be the well of Gaja Mada while an indentation on a rock surface in Ballu called tapak kakai Maja is claimed to be the footprint of Gaja Maja.

Camat Titus B. Duri at the Sumur Maja or Gaja Mada well just outside of Ledeunu

All of these and many other stories are central to the way that Raijuan and Savunese people view the world and underpin their social traditions and structures. However they throw only limited light on the early history of the islands. They might include the folk memory of a tsunami, and suggest that the first immigrants arrived from the west, perhaps via Sumba. Possibly Raijua was settled first before Savu. Cultural traits such as the high status of women and serial adultery seem to have been endemic.

Return to Top

A Brief Colonial History of Raijua

While there is an abundance of mythical stories about Raijua there is a sparse amount of documented history. Even so it seems clear that indigenous leaders ruled the island long before the arrival of the Europeans.

The first navigators to venture across the Savu Sea were early Portuguese merchant adventurers. There was nothing on barren Raijua or Savu to attract any of them. Even so it is clear that some Portuguese navigators were aware of both Savu and Raijua.

Inspired by Malaysian legends of ‘Islands of Gold’, the Malaccan-born Portuguese mathematician and cartographer Emanuel Godinho de Eredia secured a commission from Philip I of Portugal in 1594 to discover the islands south of India – so-called Meridional India (Mills 1997, 2-3). In 1600 the Viceroy of Goa, Ayes de Saldanha, issued a further commission and Eredia returned to Malacca to prepare for his long planned expedition. Unfortunately a succession of attacks by Malays and the arrival of a Dutch fleet in the Straits of Malacca frustrated his ambitions and he was forced to remain in Malacca.

Still obsessed with Meridional India he published a chart in 1602 depicting the Lesser Sunda Islands and Australia, which some have assumed was a work of fantasy since it includes eight phantom islands identified by Marco Polo. The supposed land of Ouro or 'Gold' aligns with the coast of western Australia (Spate 1966; Richardson 2006, 49). However many of the details depicted in the chart are so precise that they can have only been gathered from knowledgeable navigators. One detail highlights a voyage from Ende Island around the west coast of Sumba, through the Raijua Strait separating Raijua (marked as ‘Rajoan’) and Savu, and on to the remote Ashmore, Cartier and Seringapatam Atolls that lie between Indonesia and Australia, the latter marked as Luca Vea or ‘beach’.

Detail from a chart showing a voyage through the Strait of Raijua

(Nova Tavoa Hydrographica do Mar de Novas Teras do Sul by Emanuel Godinho de Eredia, 1602)

The Dutch VOC first made contact with Savu in 1636, when one of their vessels was shipwrecked on the island and only a minority of the crew escaped to Bali. A Dutch squadron rescued the remainder in 1645. Hendrick ter Horst, the resident of the Dutch fort on Solor, set sail for Savu in 1648, having been made aware that slaves from Savu were being sold to the black Portuguese at Larantuka in defiance of VOC regulations. He secured trade contracts with three rulers on the mainland, one of which was Dimu, under which they agreed they would not trade in slaves (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 156).

It seems that Raijua also sought a relationship with the VOC, but Willem Tange, who was the Resident of Timor from 1684 to 1685, had a low opinion of the islanders (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 237):

The Island of Savu which is somewhat distant is of the same character [as Rote]. And its conflicts emanate from the Island of Raijua attached to the same land. They are by nature a people that is much more quarrelsome and robust, and want to join into the Noble Company enterprise. They frequently meddle into the conflicts of the Savu people, and light-heartedly choose sides against gifts.

The Raijuans had a close link with the seafaring Makassarese, who traded throughout the region independently of, and in competition with, the Dutch.

According to local genealogies the first Raja of Raijua appears to have been Baku Ruha a member of udu Nada Ibu who probably ruled in the mid-seventeenth century. His ancestors came from Liae on Savu and he was married to a woman from Dimu and therefore presumably allied to that Savunese domain. He appears to have had no contact with the VOC (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 240). Ties between Raijua and Dimu remained strong for many generations to follow.

The elder brother of Raja Baku Ruha was Alo Ruha, a priest at Ketita. Alo Ruha’s son, Mau Alo, had been the fettor (executive regent) of Upper Raijua and may have later become the island’s second Raja (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 241). He was certainly a man of considerable power but became involved in a feud with another Raijuan chief called Hebu Wadu and was eventually forced to seek exile, sailing to East Sumba and allying himself to the rulers of Rindi. When Mau Alo later attempted to land back on Raijua he was immediately attacked by Hebu Wadu and fled to saftey at Dimu. A later VOC record dated 1680 noted that Mau had been recently executed in Dimu for mistreating a local chief (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 241).

Mau Alo highlights the close long-term link between Raijua and East Sumba. While Raijua was dry and barren and water and food were scarce, Sumba was quite the opposite. Some Raijuans (and Savunese) risked the 100km crossing to the east coast of Sumba at the start of the dry season, returning before the onset of the rainy season. This resulted in some intermarriage between the two domains.

Despite its small size, Raijua was not a peaceful island. A 1692 report suggests that at that time it continued to be wracked by internal feuds (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 244). Its tough conditions had bred a tough people and they had been embroiled in a long-standing dispute between Upper Raijua and Lower Raijua.

Apparently two years prior to 1693, Raja Mandi of Mangili, a domain in southern East Sumba, had sailed to Raijua to meet Bali Lai, either a local chief or the third Raja, asking for assistance in approaching the VOC to obtain the Dutch flag and trade sandalwood with them (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 242). Mangili was then the main source of sandalwood on Sumba. Two year later, the opperhoofd (upper head or chief) of Kupang, Willem Moerman, sailed to Dimu to meet the local fettor Luji Talo and request that he join him on an expedition to Melolo where the VOC hoped to source sandalwood and slaves. Bali Lai joined the meeting and recounted his discussions with Raja Mandi, explaining that he wanted the VOC to intervene in a dispute between Raijua and Melolo – one year previously the second regent of Melolo (Rindi) and his perhau’s crew had been massacred on Raijua.

Bali Lai and Luji Talo accompanied Moerman’s expedition to Melolo and their ship’s captain had positive discussions with Raja Sama Taka of Melolo and Raja Mandi of Mangili. However the Sumbanese had for a long time traded with the Catholic merchants of Larantuka, the Larantuqueros, and of Sikka, neither of who had any desire for the VOC to establish trading links with Sumba. When Moerman met Raja Mandi in the presence of Bali Lai and Luji Talo a few days later he was told that he dared not sell sandalwood to the Dutch because he had committed to sell it to Flores later that year. It seems that Bali Lai remained on Sumba. According to a 1698 VOC report he was later murdered by ‘the wild islanders’ (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 243).

According to local oral history, Baku Ruha’s son, Haba Baku, eventually became Raja, presumably around 1700, and was succeeded by his son Nyèbe Haba. Nothing else is known about them.

In 1702 some 18 Raijuans became stranded at Kupang while their perahu was under repair (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 244). They set sail in the company of a VOC sloop Doradus, but soon overturned in the Semau Strait. The crew were taken onboard the sloop and returned to Raijua, where their chiefs expressed their thanks and accepted a VOC flag. However this act seems to have had no long-term diplomatic consequences.

The Hoge Regeríng, the supreme authority of the VOC in Batavia, were so concerned about the intentions of the Larantuqueros of Larantuka on Timor Island (who were known to the Dutch as Topasses) that in 1756 they despatched their commissioner, Johannes Andreas Paravicini, on an important diplomatic mission to Kupang. His objective was to persuade the regional chiefs to trade with the VOC not the Topasses. There in Kupang he obtained signatures on a contract of allegiance with a selecion of leaders from the islands of Solor, Savu, Rote, Timor and Sumba (Fox 2003, 12; Wellem 2004, 19; Hägerdal 2012, 376-381). These included the Rajas of the five domains of Savu – Seba, Mesara, Menia, Timu and Liae – but not the leader of the island the VOC referred to as Randjoewa.

Clearly the VOC were well aware of Savu’s tiny neighbour, but considered that it was inhabited by ‘still uncivilised people’ (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 244). The opperhooft of Kupang made an approach to the island and in 1758 the Raja’s brother, Lai Nyèbe, travelled to Kupang to meet him along with the other rulers on Savu. The following year a Leo Nyale, the chief of Anadenka, the second negeri on Raijua, visited Kupang and swore an oath of loyalty, adding his signature to the Paravicini contract of allegiance. VOC records suggest Leo Nyale was Raja of Raijua from 1759 to 1761 alongside Lai Nyebe, but this could be a misunderstanding (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 245). Oral histories record that only Lai Nyèbe was Raja and appears as such in VOC reports up to 1790.

Meanwhile around 1760 the VOC placed a representative on Savu: Johan Christopher Lange a native of Saxony. Based at Seba he routinely visited the island’s Rajas, encouraging them to grow crops for the Dutch garrison at Kupang. When Captain James Cook landed HMS Endeavour at Seba in 1770, he met Lange, as did his botanist Joseph Banks and his journalist John Hawkesworth. Cook recorded that the Dutch had formal relations with Seba (which then incorporated Menia), Mesara, Timu and Liae on Savu as well as with Regeeua [Raijua], each of which was governed by its respective Raja or King (Cook 1784, 121). The journalist John Hawkesworth was told that Savu was composed of five principalities or negeri, one being ‘Regeeua’. To defend itself the island could, at short notice, raise 7,300 warriors of whom 1,500 were from Regeeua (1773, 288).

HMS Endeavour dangerously grounded on the Great Barrier Reef in June 1770, three months before its arrival on Savu. By Samuel Atkins.

It seems that to Hawkesworth, Regeeua was just a name. From the following comment he did not seem to realise it referred to Savu’s small neighbour (1773, 296):

While we were at this place, we made several enquiries concerning the neighbouring islands, and the intelligence which we received is to the following effect:A small island to the westward of Savu, the name of which we did not learn, produces nothing of any consequence but areca-nuts, of which the Dutch receive annually the freight of two sloops, in return for presents that they make to the islanders.

Joseph Banks repeated the same statement in his journal, first noting that:

beginning with the small Island to the westward of Savu called Pulo .....

Lange clearly gave them its name but they did not record it.

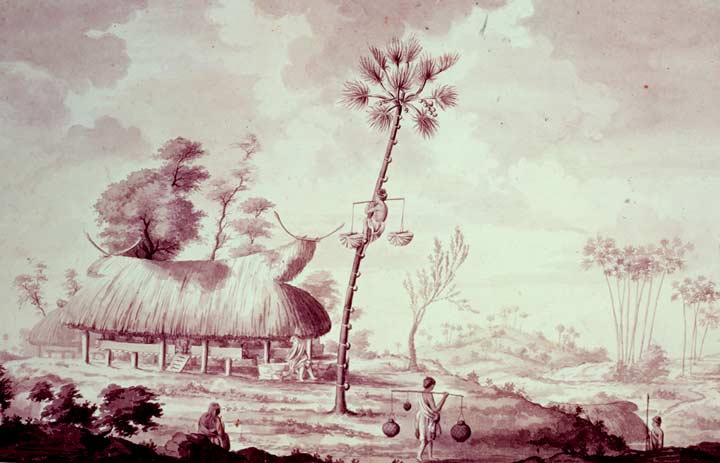

Drawing of the chief’s house on Savu by Sydney Parkinson in 1770

British Library, London

When Cook departed from Savu on 21 September he sailed west along the north coast of both Savu and Raijua before turning SSW and sighting Dana Island.

The French navigators who followed Cook referred to Raijua as Benjoar, clearly a corruption. When Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux sailed from New Guinea to southwest Australia on La Recherche his vessel took a circuitous route along the north coast of Timor and then out into the Indian Ocean, on 25 October 1792 passing just two miles to the north of Savu and Raijua. Although he had a good view of the Raijua Strait, he remarked that the appearance of the two islands was so monotonous it was impossible to identify any features of note (De Rossel 1808, 172). As they sailed past the two islands their vessel fought against very strong currents, forcing the crew to increase the frequency of taking bearings to ensure they were not drifting off course.

Shortly afterwards on 21 September 1801 the French naval corvette Le Naturaliste also crossed the Raijua Strait. On board was the cartographer Louis de Freycinet who mysteriously recorded Benjoar as high, well wooded and inhabited (Freycinet 1815, 356-357).

Although cartographers were now fully aware of the location of Savu and its small western neighbour, there were still misunderstandings. A British map of 1801 labelled Raijua as Benjoar and included the tiny phantom island of Timo just offshore from the southeast coast of Savu (Müller 1857, 277). According to Hawkesworth, Timo was a safe anchorage on the southeast coast of Savu, now known as Timu Bay (1773, 277).

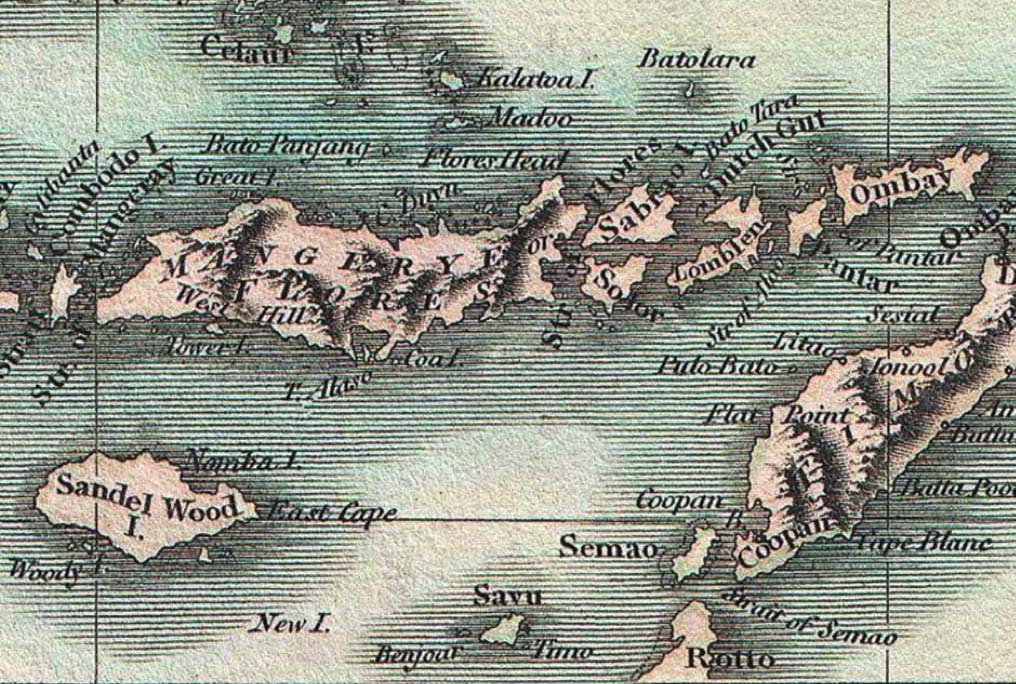

Above and below: Details from A New Map of the East India Isles by John Cary, London, 1801

Raja Lai Nyèbe probably died shortly after 1790 and was succeeded by his son, Jara Lai, who is mentioned in a VOC report of 1794. The fettor of Raijua from 1771 had been Lomi Tulu, who died in 1794 and was followed by his son Raja Tulu.

Oral tradition mentions that Raja Jara Lai was succeeded by his brother, Mau Nyèbe, and later his son, Kote Lai. It appears that on Raijua, although the line of ruler remained within the same lineage it was rare for the title to pass directly from father to son. Raja Kote Lai seems to have had a bad reputation as an abuser of women and might have even raped a relative of his fettor Dohi Lado (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 299). In 1807 the Dutch representative on Savu reported a serious feud between the Raja and his fettor – the latter having set fire to the Raja’s land. Dimu sent warriors to Raijua to support Raja Kote Lai but Dohi Lado sought help from Rajas opposed to Dimu whose warriors forced the troops from Dimu to leave before they could rescue the Raja. Local stories tell how Dohi Lado then enticed Raja Kote Lai to a cave at Ballu and killed him. Raja Kote Lai’s three sons fled Raijua, one to Ndao Island, one to Dimu and one named Ama Mehe Tari to Seba, where he later married a local woman.

The Raja of Seba seemed willing to provide an on-going supply of men, either to support the Dutch militarily or to provide reinforcements to the Rajas of Sumba (Fox 1977, 163). Many of these were warriors from Raijua. Some of the latter supported the Dutch in their campaign against the Raja of Amanuban in western Timor, probably at some time between 1814 and 1822. One heroic warrior – Nera Bia from Boko in Kolorae – is still remembered by his descendants in that hamlet where his house is still standing. He managed to infiltrate an Amanuban fort and start a fire, allowing Dutch troops to enter (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 300).

According to an 1831 report by the government commissioner E. Francis, immigrants from Savu had established their own kampong on Sumba following a royal marriage alliance between the Raja of Melolo and the Raja of Seba (‘Kupang in 1831’ 1838, 366; Roo 1906, 241). A second colony was established at Kadumbu on the northeast coast of Sumba in 1848 as a result of a marriage alliance between ruling families from the two islands (Wijngaarten 1893; Fox 1977, 164; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 318). It seems these immigrants also arrived with their wives and children (Gronovius 1855, 304). Some of the closest ties with Savu and Raijua were between the eastern coastal regions of Mangili and Waijelu (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 318). Some of the Raijuan immigrants settled in two Mangili coastal fishing villages – Maukawini and Benda.

We have no information about the two Rajas who followed Kote Lai – Leo Nyèbe, the son of Nyèbe Haba, and Ledo Teni, a descendant of Alo Ruha. Around 1830 Kote Lai’s son, Ama Mehe Tari, seems to have returned to Raijua from Seba to become Raja. He had been schooled in Kupang. In 1849 his rule appears to have been challenged by an uprising led by another of the island’s fettors. A fettor on Savu dispatched 14 warriors in a perahu but it was blown off course in the Raijua Strait and was shipwrecked on the south coast of Flores near Sikka (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 303).

As already stated, life on Raijua was tough. The German naturalist Salomon Müller noted in 1857 that in dry infertile years the inhabitants suffered famine for many weeks. Increasing contact with Europeans led to the outbreak of a devastating smallpox epidemic on the Savu mainland in 1869, which wiped out nearly half of the population. This seems to have quickly spread to Raijua causing similar devastation. A Dutch report of 1872 noted that in one village of 300 inhabitants only one child survived (Donselaar 292). To combat the epidemic the Raijuans decided to sacrifice a slave, who was drowned in the Raijua Strait separating Raijua from Savu. The pandemic must have devastated the island. Adriani et al claimed that the popualtion of Raijua was halved, its 6,000 residents reduced to 3,000, crude round numbers that were probably overestimates (1877, 8). Bodies were removed from the houses with difficulty and were sometimes devoured by greedy pigs or hungry dogs. In 1890, Raijua’s 25 different tribes had a combined population of just 1,276 (Ten Kate 1894, 700) but had recovered to 3,836 by 1924 (van der Wetering 1926, 487). It is today 10,000.

Duggan and Hägerdal suggest that Raja Ama Mehi Tari might have been a victim of the devastating smallpox outbreak. According to folk memory he was succeeded by three rulers, none of whom are mentioned in the colonial records – Mehe Tari, Heke Tari and Kale Huna – so if they existed it may be that they too perished in quick succession.

In 1869 the Dutch authorities at Kupang acknowledged the great grandson of Kote Lai, Ama Loni Kuji, as the next Raja of Raijua. He would reign for 46 years until 1915.

After the epidemic the Kupang-based missionary Donselaar visited Savu in 1870 and encouraged the Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap (the Dutch Protestant Missionary Society) to place a permanent missionary on the island (Walker 1980, 3). Later that year the missionary Mattheas Teffer arrived on Savu where he remained until 1883 (Steenbrink 2003, 205). During his long sojourn he visited Raijua, which was then completely pagan (Adriani et al 1877, 25). In 1874 Teffer reported that:

The island of Randjoewa remains more isolated [than Savu], and as its docile servant plays a completely subordinate role (1875, 206).

The implication is that by then the local feuding on Raijua had ceased. The Raijuans appear to have found a way of replacing warfare with ritual cock fighting (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 71). Two ritual cock fights were held on two consecutive days on the border between Upper Raijua and Lower Raijua. On the first day the fights take place in an arena containing a stone dolmen, a memorial to the many warriors who perished in the long running conflicts. The two days of ritual cockfights were followed by many days of recreational cockfighting and gambling between the two same ritual domains.

Teffer noted that in terms of its soil, production and population Raijua was like a miniature version of Savu. The Raijuans occasionally sailed to uninhabited Dana Island, to collect the goats that roamed freely there in some numbers.

The missionary’s visits to Raijua achieved limited results. By 1876 some 90 islanders had been converted, including Raja Ama Loni’s children. An Ambonese teacher was sent to the island, but made only 35 converts in 3½ years. Many converts left for Sava and Sumba, so by the mid-1880s there were only 19 Christians left on Raijua (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 350). When the missionary Johan Niks visited Raijua in 1885 he was not allowed to hold a service with the few remaining Christians or conduct any baptisms. He realised that it was nigh impossible to preach to the Raja.

The royal compound of Udju Dima

In March 1882, a powerful cyclone destroyed thousands of lontar palm trees on Savu and also devastated the maize crop (Teffer 1889, 153). It would undoubtedly have had the same effect on more exposed Raijua, leading to more hunger and hardship.

In May 1888 the Utrecht born Philippus Beiger, a Protestant missionary working for the Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap, arrived on Savu, having been assigned to the Prince's Church on Rote Island. Earlier in 1879 the Dutch had combined Savu and Rote into a single administrative unit. Bieger had previously proselytised in central Java. At some stage while on Savu he visited Raijua, which he found to be poorer than the main island. In his opinion ‘there [was] nothing at all on Raijua’, ships and steamers never went there. The islanders mainly lived on lontar palm syrup but some ‘Turkish wheat’ (sorghum?) was grown although hardly any rice (1889, 151). A large flock of sheep and goats roamed on uninhabited Dana Island, but sacrifices were required before the Raijuans sailed there, believing ‘it is full of devils’. In 1890 the NZG missionary Hendrik Kruyt noted that the voyage to Dana only took place every sixth year. Dana was considered a sacred island and was visited in order to make offerings to the ancestors.

The church at Seba on Savu in 1888 photographed by Philippus Beiger

The Raja of Raijua was still a pagan although there had been a Christian teacher visiting the island who had since died. Beiger thought it would be a pity if the missionary work did not continue although any new teacher would need to be a good sailor. The crossing from Savu was not only dangerous but also completely impossible in the rainy season. There were strong currents in the north and south of the Raijua Strait and when they met they created a dangerous circular water flow, which could trap a small perahu. Once caught a boat might be trapped for three days or more in the intense rays of the sun and without water. In some cases a boat could be carried off to Sumba. Beiger was amazed at the patience, persistence and courage of the local sailors in their small boats, crafted from wood that was often rotten.

Nevertheless despite the strong currents the people crossed from Raijua in their canoes to trade and barter, bringing mats, boxes of betel chew and such in return for sugar, tobacco and cloth. In 1890 there was a very poor maize harvest on Savu but not on Raijua, so the tables were turned. Many Savunese sailed to Raijua that year to barter for food (Duggan and Hägerdal 2018, 305).

Faced with so many minor wars and uprisings across the East Indies, the Dutch were reappraising their policy of zelfbestuur, ruling through local chiefs and Rajas rather than directly. The first important change in the Residency of Timor began in 1904 when the Resident of Timor, F. A. Heckler, deposed the troublesome Raja of Larantuka. That same year Colonel Joannes van Heutsz became the new Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, having finally put down a long-running insurgency in the Sultanate of Aceh. Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule.

Colonel Joannes B. van Heutsz

When J. F. A. de Rooy took over from Heckler in March 1905 he received clear instructions regarding this new policy. His main task was: To establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the implication of a new strategy towards the self-ruling districts, which are the majority of the whole area. The former policy of non-intervention, suggesting that the supreme authority was with the native rulers and not with the colonial authority, should be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70).

Most of the territories supervised by Kupang did not resist – the exceptions being Ende, Ngada and Manggarai on Flores and Sumba Island. In 1906 W. F. de Nija was appointed the posthouder of the afdeeling of Rote and Savu (an administrative section of the Residency), while F. G. W. Nowack became the first civiel gezaghebber of onderafdeeling (subsection) Savu (Regeeringsalmanak voor Nederlandsch-Indie 1907). On Savu the Dutch constructed a new administrative centre at Menia, northeast of Seba.

Over the next decade the Dutch gradually consolidated the traditional fragmented system of governance on Savu. When the Raja of Dimu died in 1910 he was not replaced and Dimu was merged with Seba. When the Raja of Mesara died in 1914 he was not replaced and Mesara was merged with Seba-Dimu. Then in December 1916 the Raja of Seba, Semuel Thomas Djawa (locally known as Logo Rihi and installed in 1907) was appointed Raja of the new complete landschap of Savu. From now on he and his district heads were obliged to provide corveé labour to construct the roads that would link the four domains on Savu. Meanwhile males aged 17 or more were now required to pay tax on their harvests.

On Raijua the Dutch had began to collect taxes as early as 1912 (Kagiya 2010, 107). In April 1915, Raja Ama Loni Kudji had died and the Rajadom passed to his son, Ama Meda Lai, who became the first leader of Raijua to be baptised, adopting the Christian name of Paulus. However his reign was short. In April 1918 the Dutch honourably discharged him from his position along with the Raja of Liae. The Assistant Resident of Kupang described Raja Paulus Lai as ‘no Napoleon, but a splendidly impressing figure with sharp and noble facial characteristics and a fiery glance’. He died two months later.

The graves of the last Raja of Raijua and his wife. Raja Ama Meda Lai Kudji died on 16 June 1918

In his final report of 1920, A. H. M. J. Heyligers, the gezaghebber of Savu Raijua, explained the simple manner in which the island’s domains were governed. The appointed Raja of the whole island was still Semuel Thomas Djawa, the twelfth Raja of Seba, who was assisted by the fettor of each of the landschaps of Seba, Timu and Mesara, and the doae of each of Liae and Raijua, the latter two being the sons of the previous Rajas. The relationship between the Raja and the district chiefs was amicable, helped by the fact that the district chiefs had close blood ties with each other. The Raja accompanied the governing officer on his tours of the islands along with its local fettor or doae, during which they issued instructions for improvement works and checked that previous assignments had been satisfactorily completed. The gezaghebber also held a regular conference with all the heads.

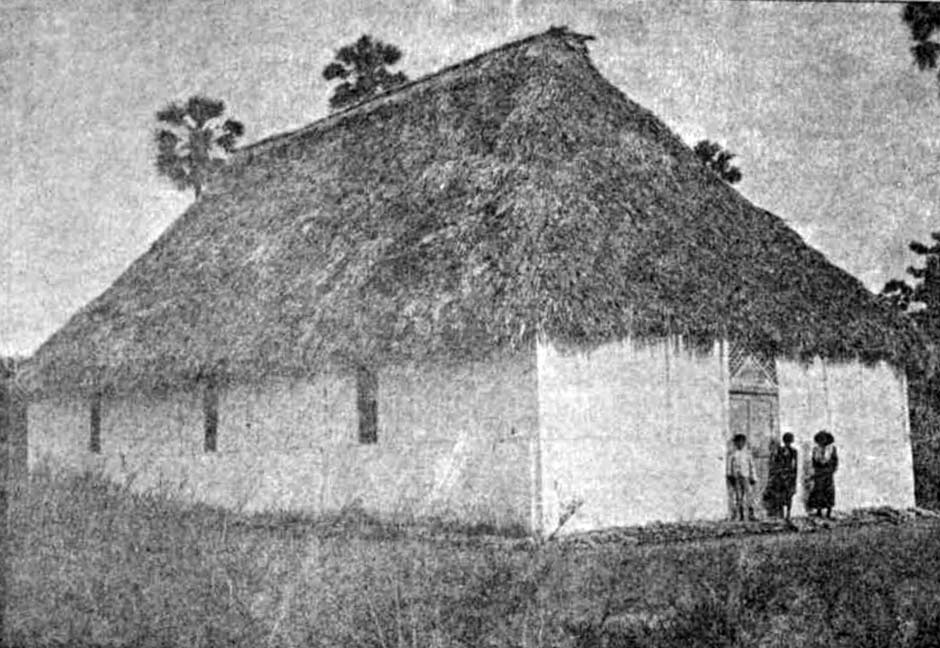

Heyligers reported the population of Raijua in 1920 as 3,474, the largest settlement being Udju Dima:

The population of Raijua in 1920 according to Heyligers

The only anchorage on Raijua was at the beach of Udju Dima although the island had only 8 prahau. The sea roads were not always navigable during the west monsoon and even steamers heading for Seba could sometimes not land and had to moor at Banjo on the east coast of Savu. There was one church, established by the Nederlandsch Indische Protestantische Kerk, and a cleric who also provided elementary schooling for around 40 children whose parents were willing to accept Christianity (Heyligers 1920).

Poor health remained a severe problem in the onderafdeeling. In 1925 Van der Wetering undertook a study of infant mortality across 15 different villages on Savu and Raijua (1926, 488). Of the 1,087 children born by 154 women (an average of 7 per mother), 344 (31.6%) died.

At some stage Pia Lai, the son of Ama Meda Lai, became the fettor of Raijua – he certainly held that role from 1940 until his death in 1954. In 1942 some 30 Japanese soldiers were stationed on Savu, their commanding officers requisitioned the residence of the Raja in Seba. Semuel Thomas Djawa retained his position as the island’s traditional chief. There is no information whether the Japanese army had any influence on Raijua.

In 1954 and 1955 Raijua suffered from an extended period of drought and severe famine. Pia Lai’s son, Jeremia or Heremia Huru Kudji, took over as fettor in 1956, two years before the introduction of a new system of regional government in which the hereditary noble rulers were stripped of their political powers. In 1958 Savu and Raijau became part of the newly formed Kupang Regency, administered from Kupang on Timor. At this time there was no camat assigned to Raijua. Heremia Huru retained his honorary title until his death in 1990.

Just like their mainland cousins, the Raijuans had resisted western education and religion. However everything changed after the attempted communist coup of 30 September 1965 in Jakarta. The subsequent purge of the PKI (Parti Komunist Indonesia) and its supporters by Suharto resulted in mass killings and even had repercussions on remote Savu. The military arrived on Savu Island in the last quarter of 1965 and forcibly arrested and imprisoned anyone thought to be associated with the PKI, using arbitrary beatings and torture (Pa and Wiwi 2015, 38). Shops in Seba were set on fire. At the end of March 1966, thirty-four men who were either Communist Party officials or were branded as communists were publically executed without trial using explosives and machetes. Twenty of them were teachers. The extreme violence created a widespread climate of fear. After 1966 anyone associated with Jingi Tiu was considered to be ‘without religion’ and regarded as a threat. Under Suharto's New Order a large proportion of the population converted to Protestant Christianity, especialy during the 1970s and 1980s.

New churches sprung up on Raijua but otherwise there was little other development. Even in 1981 there was still no regular ship plying between Savu and Raijua.

In the June 1992 national elections, the majority of Raijuans voted for Golkar, the ruling party. As a gesture of thanks the government arranged for a naval warship to dock at Namo carrying gifts of instant noodles, generators and TVs (Kagiyo 2010, 210). It also had some 30 medical experts on board to offer temporary health care to the islanders. Later that year Raijua became a kecamatan or formal sub-district, empowered to improve public services. In 1993 the first camat of Raijua was installed - Elias Susi, a native of Ndao.

Work finally began on improving the islands roads and installing small embung water reservoirs. This modest opening up of the island resulted in a change of culture and an increase in crime, especially the theft of heirloom textiles. Since 1995 an increasing number of residents have left Raijua to find work elsewhere in Indonesia or in Malaysia (Kagiya 2010, 211).

The gathering and farming of seaweed was introduced on Savu in 1986 and increased markedly in 1989. In 1997/98 it was introduced to Raijua since when many islanders have discovered that they can make a better income by farming seaweed instead of tapping palm trees. In the mid-90s the first satellite TVs appeared on the island, powered by portable generators, and villages were finally exposed to the wider world. Demand for the island’s high quality seaweed increased steadily but suffered a setback in 2009 when an oil spill adversely affected production. By 2010 a significant portion of the working population was involved in seaweed farming as a result of which most of the island’s palm syrup had to be imported from Savu.

The office complex of Kecamatan Raijua at Namo. The camat's ofice is on the left.

In 2008 Sabu Raijua was separated from Kupang Regency to become a kabupaten in its own right, the intention being to increase public investment in education, health care and infrastructure. Raijua quickly benefited from a better connection to Savu after a small ship began sailing between the two islands three times a week. Since 2009 the camat of Raijua has overseen numerous local projects, ranging from the construction of schools and a clinic, the expansion of Namo harbour, and a modest improvement in roads around Ledeunu. However it is only in the past few years that serious road improvements have got underway and Raijua has finally been connected to the national mobile telephone network.

2020 development plans for the road network and ebungs around Ledeunu

Although the island’s nobility is no more, a great grandson of the last Raja of Raijua still lives in the royal enclosure of Udju Dima, where he is the custodian of the remains of a huge Dutch flag said to be several hundreds of years old, which he inherited from his great grandfather. Every five years the descendants of the last Raja hold a celebration where a buffalo is sacrificed and the Dutch flag is flown.

Above: Leonard Albert Lai Kudji, the great grandson of the last Raja of Raijua, Ama Meda Lai Kudji. Below: with the remains of the old Dutch flag at Udju Dima

Return to Top

The Indigenous Rulers of Raijua

| Ruler | Title | Dates | Notes |

| Baku Ruha | Raja | ca 1650 | A member of udu Nada Ibu. Married to a noblewoman from Dimu on Savu. |

| Mau Alo? | Raja | ??-1680 | |

| >Bali Lai? | Raja | ??-1698 | |

| Haba Baku | Raja | ?? | Son of Baku Ruha |

| Nyèbe Haba | Raja | ?? | Son of Haba Baku |

| Lai Nyèbe | Raja | 1756-1790 | Lai Nyèbe seems to have been the chief of Anadenka, the second negeri of Raijua. Mentioned in 1767 and in VOC reports up to 1790. |

| Jara Lai | Raja | fl. 1794 | Lomi Tulu was fettor from 1771 until his death in 1794. |

| Kote Lai> | Raja | ??-1807 | Murdered in 1807 by his fettor Dohi Lado |

| Leo Nyèbe | Raja | ? | Son of Nyèbe Haba |

| Ledo Teni | Raja | ? | A descendant of Alo Ruha |

| Ama Mehe Tari | Raja | 1830-1868> | Son of Kote Lai. Also known as Messe Tari. |

| Mehe Tari | Raja> | ? | |

| Heke Tari | Raja | ? | |

| Kale Huna | Raja | ? | |

| Ama Loni Kudji | Raja | 1869-1915 | Great grandson of Kote Lai. Died 07 April 1915. Ama Dj’aga was his fettor or vice-regent from 1905 to 1907. |

| Ama Meda Lai Kudji | Raja | 1915-1918 | Son of Raja Ama Loni Kudji. Born 1865 and died 16 June 1918. He was the first Christian Raja of Raijua, baptised as Paulus. The last independent Raja of Raijua. |

| Pia Lai | Doae | ??-1954 fl. 1940 |

The first doae of Raijua. Died in 1954. |

| Jeronimus Huru Ludji | Doae | 1956-1958 | The last doae of Raijua. Also known as Ratu Jadi and Heremia Huru. Born ca. 1901 and died 18 April 1990. |

Sources: Donald Tick 2018; Duggan and Hagerdal 2014, 238, 302 and 523-524

Return to Top

Social Structure – Udu, Kerogo, Hubi and Wini

Just like their Savunese cousins, every Raijuan simultaneously belongs to two separate kinship groups (Kagiya 2010, 21):

- a localised male patrilineal clan known as an udu (meaning cluster). There are 13 on Raijua. Udus play important roles in land and palm tree ownership and in religious and political affairs. They also perform agricultural ceremonies. Each udu has a leader called a banggu udu and is under the ritual control of male priests called mona ama. The highest-ranking priest is the deo rai or ‘lord of the land’. Udus are subdivided into kerogo.

- a non-localised female matrilineal clan known as a hubi (lontar blossom). There are just two: the hubi ae (greater or big lontar palm blossom) and the hubi iki (lesser or small blossom). On Raijua, the hubi ai are composed of aristocrats while the hubi iki are all commoners, while on Savu the two hubi have equal status. The hubi govern life-cycle ceremonies and are divided into sub-groups called wini (seeds). A few of the larger wini are subdivided further into from 2 to 6 kepepe, which are as autonomous as wini. In 2009 there were 71 autonomous groups (wini and kepepe) on Raijua, 27 in hubi ae and 44 in hubi iki.

The social status of every individual is determined by which matrilineal descent group he or she belongs to. One’s wini or kepepe is the most important factor in arranging a marriage or a funeral feast. In any dispute, the person from the group with the highest status prevails.

Not all of the wini are endemic to Raijua. Many reached Raijua from Savu. Other wini are found on both islands. For example wini Mako was founded by a woman from Dao Island who married a man from Dimu on Savu. Their daughter married a man from Raijua and moved to Raijua. Most members of wini Mako are found in the Seba and Dimu districts of Savu.

Wini are not named after the founding female ancestor but after the female ancestor who contributed to increasing the members and the property of that wini. Unnamed wini never had an ancestor who made such and achievement. For a wini of hubi iki to be named, additional criteria must be fulfilled; for example the female ancestor and her family must have been wealthy and she must have had at least four children, two sons and two daughters, one of each of which must have had a child!

The highest status wini from both hubi are listed below, along with their origin and number of generations founded, if known:

| Hubi Ae | Hubi Iki | ||||

| Wini | Generations | Origin | Wini | Generations | Origin |

| Mako | 8 | Dao Island | Wanynyi Rato | 42 | |

| Raja | Putenga | Endemic | |||

| Pela | 22 | Endemic | Jawuu | ||

| Pudari | 13 | Seba, Savu | Banni dao | ||

| Bangi | Seba, Savu | Banni Dare Dahi | Endemic | ||

| Lebi | Seba, Savu | Rolay Jara | |||

| Pedi | Endemic | Ga Wohe | |||

| Tii | Mesala, Savu | Radde Waga | |||

| Leha Laka | Wanynyi Tuli | ||||

| Ga Lena | Seba, Savu | ||||

| Mojo Uli | |||||

The leading wini of each hubi, along with the number of generations since their founding and their place of origin (Kagiya 2010, 100-101)

In terms of membership, the four largest wini in each hubi are as follows:

| Ranking by size | Hubi Ae | Hubi Iki |

| 1 | Pudari | Wanynyi Rato |

| 2 | Raja | Jawuu |

| 3 | Pela | Putenga |

| 4 | Mojo Uli | Rade Waga |

Each wini or kepepe has its own ritual centre called an amu ina apu (amu = house, apu = ancestress), literally house of the female ancestors, a tiny hut that can only accommodate a few women. It contains the group’s heirlooms and other common property, such as baskets of hand-woven cloth, tools and equipment for weaving, pots for dyeing and items inherited from their ancestors. Rituals are performed in front of the amu ina apu. Each wini or kepepe is headed by two pairs of female and male ritual leaders – the banni aa and mona aa respectively. The banni aa arru maddi and mona aa arru maddi are responsible for making the blue indigo dyeing pots while the banni aa arru mea and the moni aa arru mea are responsible for making the red morinda dyeing pots.

An amu ina apu ritual house on Raijua

The 13 patrilineal male descent groups udu are organised in pairs, shown below in decreasing status:

The Pairing of Udu

| Malako | Madiri Malako |

| Nadega Loborae |

Loboroli’u |

| Nada Ibu | Ledekei |

| Natua | Wuirae |

| Way | Rohaba |

| Jela | Ketita |

From Kagiya 2010, 171

Malako is the most powerful udu. The lowest status udu are highlighted in red.

The people of Raijua not only liken their island to a boat, but also their villages and houses (Kagiya 2010, 183). The traditional village is called Rae Kowa or ‘boat village'. The higher part of the village is considered the bow, the lower area the stern. Inside the house, the front and right side are reserved for men and are called the duru or bow, while the back and left side are reserved for women and are called wui or stern (Kagiya 2010, 182-183).

A traditional house at Ledeke. Its boat-shaped roof is constructed with an outward extending ridgepole and leaf-thatched roof with overhanging rukoko

A cloth called a hara is displayed at a funeral bearing the ikat motifs associated with their wini. This is so that the ancestors of their wini will recognise their affiliation in the afterlife. One of the men’s hara cloths is considered to be the sail of a boat, carrying their soul to heaven.

Return to Top

Marriage and Bridewealth

Marriage