Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Part 2

The Siboga Expedition 1899

Dutch Direct Rule 1907-1942

The Japanese Occupation 1942-1945

Post-War Developments 1945-1949

Ende following Independence

Bibliography

Part 1

Geography

Myths of Origin

Local Oral History

Pre-History of the Ende Region

Pre-Colonial History

The Portuguese on Solor

The Ende Island Mission

The Arrival of the Dutch

The Makassarese move to Ende

Endenese Piracy and Unrest

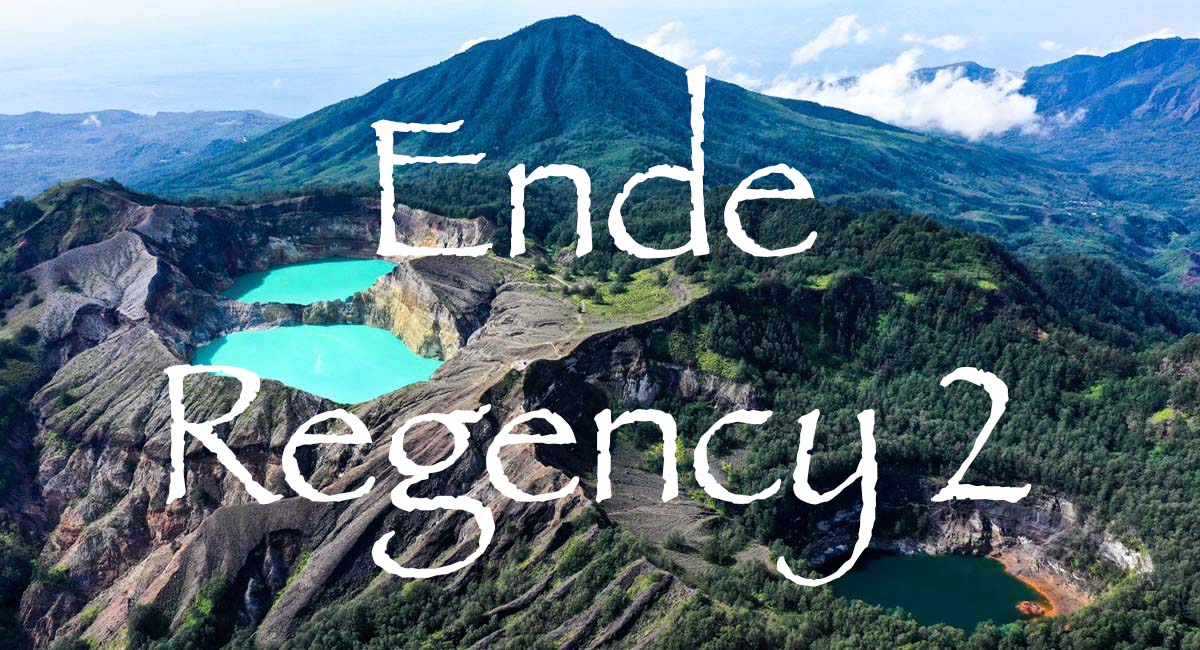

The Siboga Expedition 1899

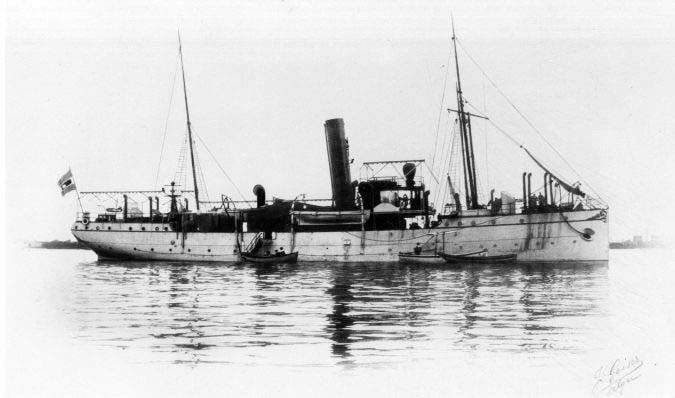

In 1899 the naturalist Professor Max Carl Wilhelm Weber led a zoological and hydrographical expedition round the Dutch East Indies aboard the 50m long twin-screw gunboat Siboga, which was owned by the Dutch East India Military Marine Service. The expedition consisted of ten Dutch naval officers, 45 native crew, six scientists including Max and Anna Weber, and two personal servants. Anna Weber was the first woman scientist to take part in a major oceanographic expedition.

The expedition left Surabaya in March 1899 but did not reach the south coast of Flores Island until February 1900, where they moored for a short time at kampong Ende in Ippi Bay. According to the expedition leader:

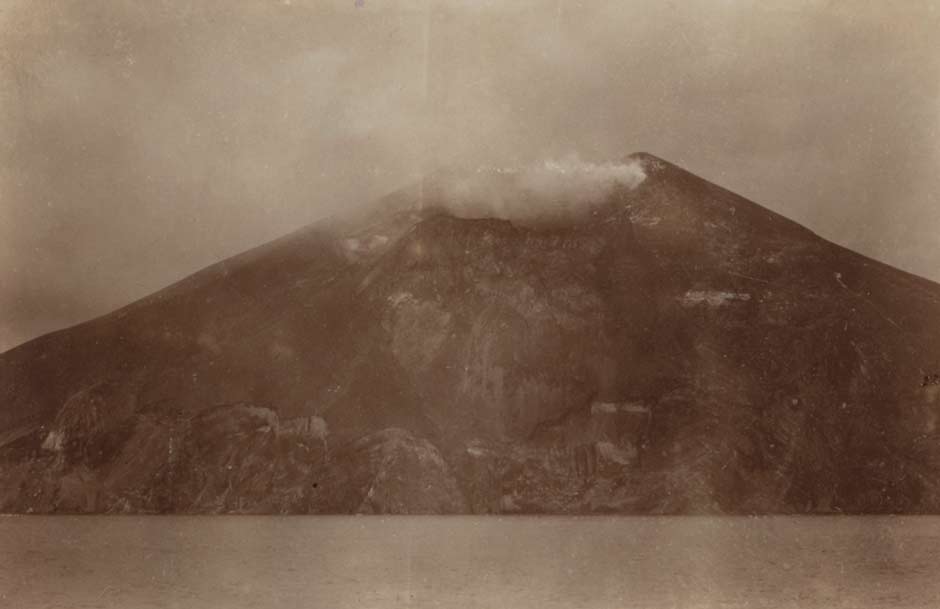

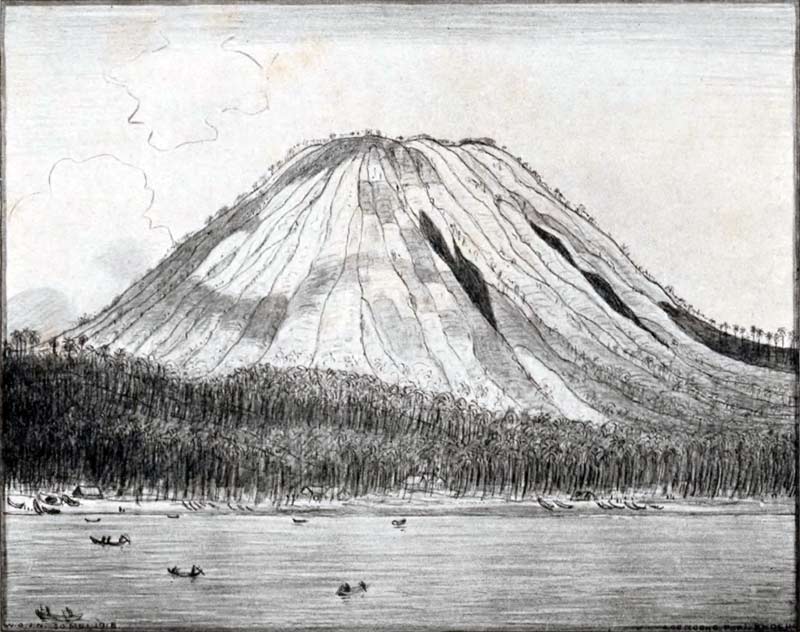

This bay is formed by a narrow tongue of land, which starts from the southern coast of Flores and ends with the arid Gunung Ija volcano, which is constantly smoking. Our photogram shows clearly the crater in the imposing cone of ashes, which continually launches a cloud of smoke (Weber 1902, 147).

Above and below: The smoking crater of Gunung Iya (659m) at the tip of the Ende promontory, also referred to as Gunung Api. Siboga Expedition.

Weber and some of his colleagues landed in Ippi Bay and walked to Ende, passing through fields of alang-alang grass planted with coconut trees and well-cultivated gardens. The posthouder Rozet informed them that a Paketvaart steamer visited the port every month, export increasing amounts of copra. There were now 50 Chinese traders based in the town whereas in 1838 there had been just one Chinese trader located on Ende Island.

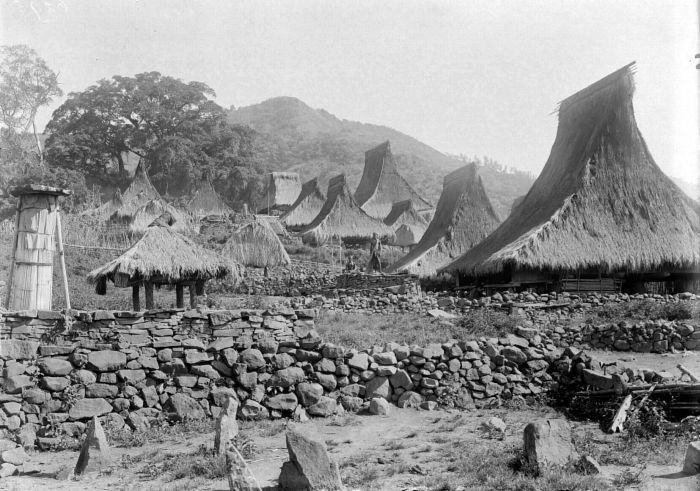

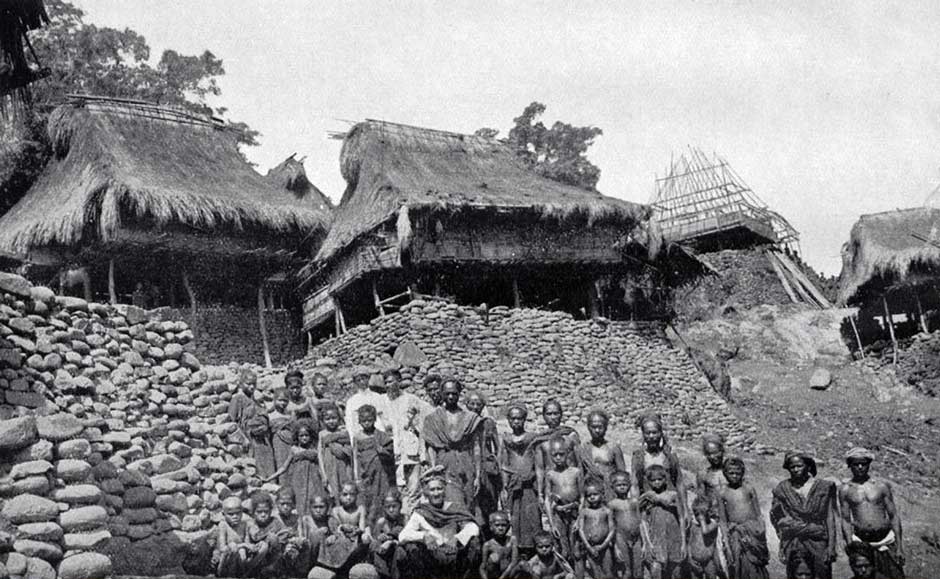

Kampong Ende photographed by members of the Siboga Expedition in 1900

Some expedition members arranged to climb Table Mountain using the son of the Raja as their guide. They landing on the beach and scaled the steep slopes of alang-alang grass to reach its flattened peak.

A magnificent panorama opened up before our eyes: the dark red, almost black peak of Gunung Iya rose up in front of us with the clouds continuously streaming by. On its slopes from foot to peak not a single blade of green grass could be seen. At our feet on the left lay Ippi Bay and the Siboga, on the right the Bay of Ende with small elongated Ende Island nesting in its middle. On the beach the numerous and closely adjoining kampongs of Ende spread out in the shade of extensive coconut groves. High, proud mountain ridges, including the steep Gunung Tonggo, jutted into the air from all sides, and on the distant horizon our eyes could clearly see the cone shape of Keo mountain.

Gunung Meja, known as Table Mountain. Siboga Expedition.

After raising the anchor the Siboga steamed past Gunung Iya before heading directly to Sapeh Bay on Sumbawa. The small volcano made a great impression with its crater facing the sea. Every now and then it was possible to see its pale yellow and red coloured inner wall through the smoke. From the foot to the crater it appeared as an enormous ash cone from which dome-shaped, red-brown rocks protruded

Return to Top

Dutch Direct Rule 1907-1942

In the last decades of the nineteenth century local wars and insurrections were widespread throughout the Dutch East Indies. In Ende, the Dutch were still suffering from attacks led by Mari Longa, especially during the period 1898 – 1902. Dutch forces eventually ambushed Mari Longa and his followers around Ndondo on Onderafdeling Maumere. Mari Longa was captured and imprisoned at Maumere but managed to escape and return to Watunggere. The Dutch attempted to negotiate a truce with Mari Longa but this turned out to be short lived.

Because of the never-ending instability, the Dutch government in Batavia had been seriously questioning their hands-off policy of self-rule in the outer islands. It was increasingly clear that peace and stability could only be achieved through direct rule.

In the Lesser Sunda Islands the first official to implement this new and more active policy was F. A. Heckler, who took over as Resident of Kupang in April 1902. He faced a problem in East Flores, where the troublesome Catholic Raja of Larantuka, Don Lorenzo II, had become engaged in territorial disputes with the Catholic Raja of Sikka and the Muslim Raja of Adonara (Steenbrink 2002a, 95). In July 1904 Heckler deposed Don Lorenzo and sent him into exile in Yogyakarta. When several Lio villages including Nanga Baa and Watu Sipi rose up against the Raja of Ende, Heckler dispatched the gunboat Maratam to Ippi Bay. That same summer his forces intervened militarily to quash an insurrection in the Sikka area (Lewis 2014, 371-375).

According to de Vries, the situation in onderafdeeling Ende prior to 1907 was that the Dutch had little influence beyond the city of Ende because in the Lio region they were always constrained by Mari Longa. Likewise on Sumba there was a saying that ‘the Endenese [pirates] have more authority than the Dutch’ (Steenbrink 2013, 106).

Since 1871 the Dutch had been waging a number of violent military campaigns to gain control of the Sultanate of Aceh on Sumatra. Between 1898 and 1903, Colonel Joannes van Heutsz headed a highly successful counter-insurgency campaign using light and flexible detachments of military police (korps marechaussee), recruited from Ambon and Java.

General van Heutsz and staff at Baté Ilië, Aceh, 1901

Following Aceh’s ‘pacification’ in 1904, van Heutsz was appointed Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies. With numerous on-going local insurrections throughout the Outer Islands, van Heutsz was in no doubt that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach and the installation of strong local rule

When the next Resident of Timor, J. F. A. de Rooy, took over from Heckler in March 1905, he was given clear instructions regarding this much more active policy. His main task was:

To establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the implication of a new strategy towards the self-ruling districts, which are the majority of the whole area. The former policy of non-intervention, suggesting that the supreme authority was with the native rulers and not with the colonial authority, should be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70).

Later that year he ordered action to be taken to subjugate some of the many local chiefs on Timor.

That same year Mari Longa attacked Dutch troops in retaliation for the deliberate burning down of Lewagare village in Dutukeli region. An attempt to capture Mari Longa in his well defended village of Watunggere the following year ended in failure.

As a first step in gaining a grip on central Flores, de Rooy despatched A. J. L. Couvreur to Ende in late 1906 as the new Controleur of Flores, tasked with assessing the situation on the ground. News of his arrival further inflamed the surrounding coastal and mountain villages. On 3 June 1907, a leader from a coastal village on the west side of Ende named Kaka Dupa, an ally of Mari Longa, attacked the government offices in Ende. This was followed on 2 July 1907 by a more serious raid on Ende led by a large number of mountain chiefs. According to de Vries, multiple villages were involved, some Endenese, some Lio – Ndatu Ko (Ndetu Ko'u), Woro Aré, Oné-Koré, Manu Nggo'o, Rowo Réké, Woro Waku, Manu Raru, Ai Bo, Watu Roga, Wora Wao, Keka Wi'i, Pu'u Pari, Kopo Nio, Nua Bosi, Woro Jaa, Woro Karo, Kori Bari, Woro Nanggé, Ndungga, Tombé Koa, Babu, Mbomba Besar, Mau Bongga (Ma'u Rongga), Numba, Péngga Jawa and Nanga Panda (De Vries 1910, 48).

A few days later, mountain villagers plundered and incinerated the whole of the town of Ende. Although many inhabitants and Chinese traders fled to Ende Island some 50 residents were killed. The incident became known as nggéra Endé (the destruction of Ende). When the merchant steamer Van Swoll arrived at Ende, the town was in ruins. The ship immediately crossed to Sumba with the news, from where the government steamer Pelikaan was rapidly sent back to Ende with troops and artillery, arriving on 11 July. The Van Swoll was sent back to Kupang to gather further reinforcements. Although the campaign against the rebels was only partially successful, many headmen to submitted to the authorities. One notable ringleader was thought to be the Raja of Ende, Pua Noté, who had met with the rebels before their attack on Ende.

The Resident of Kupang, de Rooy, decided to respond with force. The experienced military leader Captain Hans Christofffel, a veteran of the war in Aceh, was sent from Kupang to Ende with a large force of marechaussee military police (the third korps of the fourth battalion). Arriving in Ende on 10 August, his company departed for Nua Bosi on 12 August, a mountain village north of Ende town. Between 12 and 28 of August, he repeatedly patrolled the western area between Ndona and Nanga Panda. The company then left for what was then known as Rokka (Ngada), which had been in constant rebellion against the Dutch. They continued into Manggarai.

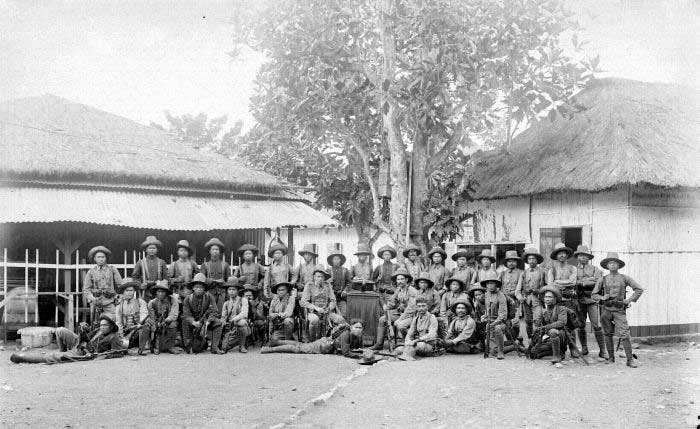

Captain Hans Christofffel

In September 1907, Couvreur replaced the local posthouder with a higher status civiele gezaghebber called Spruyt. De Rooy was of the opinion that previous posthouders were poorly educated, ineffective and had little sense of duty. Spruyt soon set to work, visiting local villages and registering and disarming the population.

Well informed about the conditions in Ende town, on 21 October 1907, the rebel leaders Mari Longa and Rapo Oja attacked Ende once again, while Christoffel and his troops were in action around Nangaba in Ngada or Manggarai (Deitrich 1989,86 ). On this occasion the rebels were repelled by residual Dutch forces stationed locally.

After a short break back in Ende, Christoffel moved eastwards into the Lio region, completing his campaign at the end February 1908. A Dutch weekly later reported one of his tactics: he promised his troops a rijksdaalder (2.5 guilders) for each head they took in the war. In one action, one soldier, Lewakabessie, killed 52 men, women and children seeking refuge in a cave and was rewarded with 52 rijksdaalder. Aware of impending attack, Mari Longa had retreated to his stronghold of Watunggere, surrounding it with defensive walls and an outer ring of sharpened bamboo stakes and thorns. It turned out to be inadequate to resist Christoffel’s offensive and Mari Longa was killed and his village overrun.

Later that year, Anton Hens was appointed as the new Controleur of Ende. Raja Pua Noté, who had been involved in the Sumba slave trade, was sent into exile, first to Alor and then to Kupang. His replacement Raja Harum, volunteered to go into exile a few months later, first to Alor and then to Mecca. In 1909 Pua Meno, his younger brother, was appointed as his replacement.

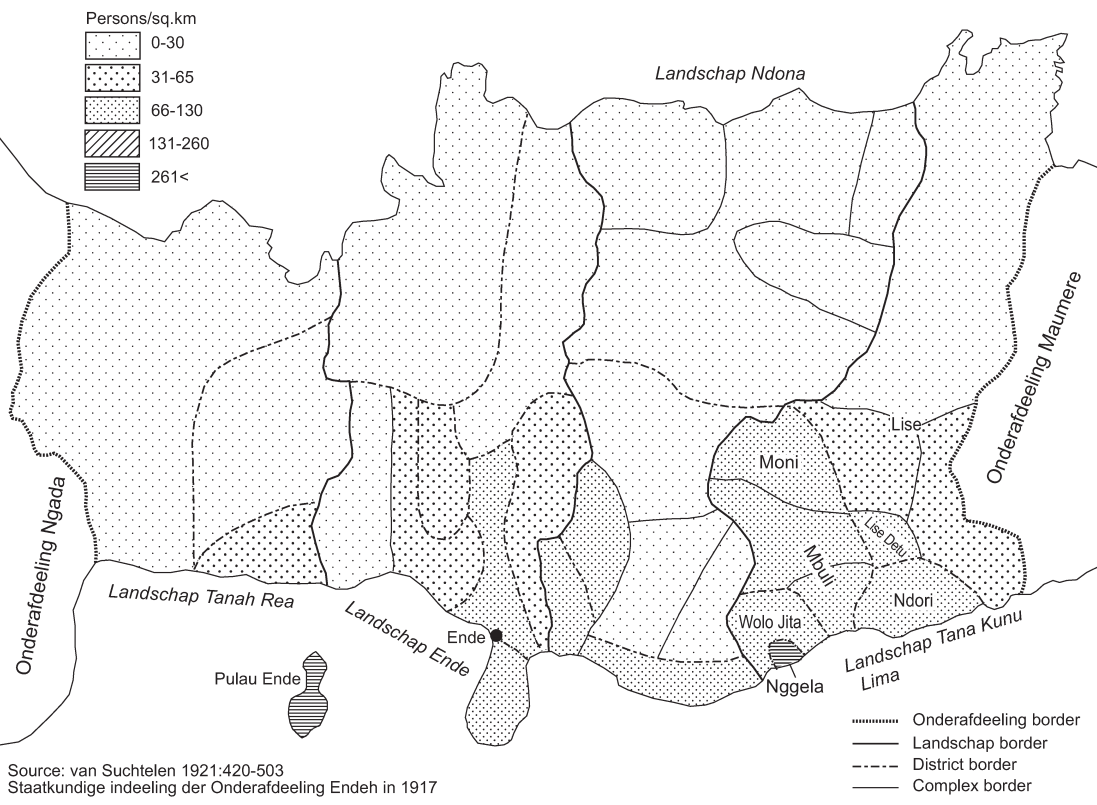

Central Flores had already been divided into two administrative subdivisions – Onderafdeeling Ende and Maumere. In April 1910 the 63 petty kingdoms of Onderafdeeling Ende were reorganised into ten self-governing districts or zelfbesturende landschaps: Tanah Rea, Ende, Ndona, Wolojita, Nggela, Mbuli, Ndori, Lise, Poe and Sooi. Kaka Dupa was chosen as the Raja of Tanah Rea and Mbaki Mbani the Raja of Ndona.

The Raja of Tanah Rea, Kaka Dupa, with his three daughters

Photographed by Charles le Roux, 1915-1919

The Raja of Ndona, Mbaki Mbani, at his palace in Wolowona

Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

The number of natives killed in the ‘pacification’ campaign was reported as 224 in 1907, 146 in 1908 and 43 in 1909. The number of confiscated firearms was 5,385 (De Vries 1910, 74-75). When news of the campaign was reported in Holland it resulted in some criticism. In mid-1908 de Rooy wondered if he had been more patient and taken twice the time with less violence he could have created a more durable success with less hatred (Steenbrink 2013, 109).

With further reinforcements from Kupang, the Controleur and the marechaussee repeatedly swept through an increasing number of villages during 1910 and pacified them.

Although the slave trade had been officially banned since the first half of the nineteenth century, it was only effectively eliminated as a result of pacification (van Suchtelen 1921, 93). Warfare had been the main source of slaves in central Flores and the main currency of slaving – firearms – had been outlawed. Meanwhile on Sumba, Dutch troops had just subjugated the slaving centre of Mamboru (Needham 1983, 35-36).

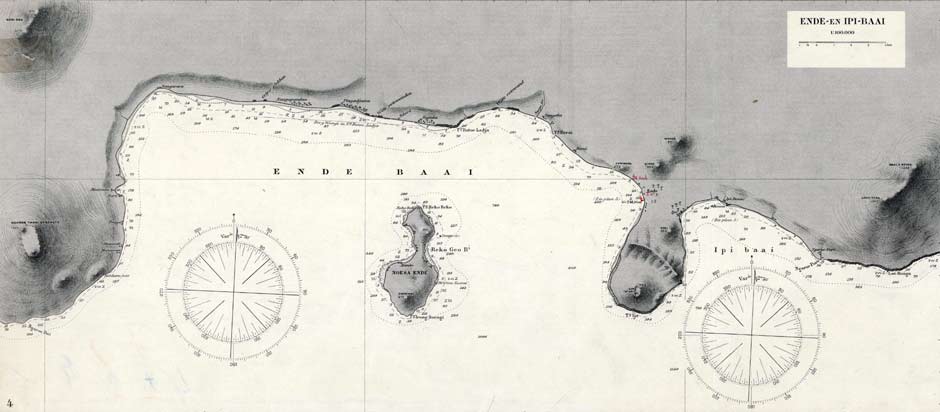

Dutch hydrographic survey of Ende and Ippi Bays dated 1910

The previous Catholic Controleur Couvreur had been concerned about the possible spread of Islam in Ende and in early 1908 had urged the priests in Larantuka to start missionary work in Central and West Flores as quickly as possible (Steenbrink 2013). In 1909, the children of the chiefs of each domain were sent to the mission school in Lela, close to Sikka, to give them a Christian education and prepare them to become local administrators (Sugishima 2006, 133). A small Catholic school was established in Ende in 1910 and second followed at Mbuli. In 1912 the gezaghebber of Ende, van Suchtelen, requested teachers for Nanga Panda, Ngaru Pero, Wayu Nesu and Nggela. In 1911 he put forward a list of 11 villages suitable for the establishment of schools. However van Suchtelen opposed the domination of the Catholic mission in Ende and respected the religious rights of local Muslims (Steenbrink 2013, 115). In 1913, Anton Hens was promoted from Controleur to Assistant Resident, with van Suchtelen remaining as his deputy. This caused some friction since Hens was an outspoken Catholic.

In 1912 a small group of immigrant Protestants arrived at Ende from Savu Island. They were skilled craftsman who worked in stone, wood and gold and settled in the Ipi district near the coast (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 285-286). It was not until 1919 that they opened a house church with a congregation of 30.

The Prefect of the Flores Mission based in Kupang visited Ende in 1914 and decided that the centre of the local SVD Catholic mission should be at Ndona, despite the fact that the village head was still a pagan. Ndona was chosen because it was in a non-Muslim area that was still close to Muslim Ende and was also next to a source of fresh water. Work began later that year and was soon extended to encompass a school with a dormitory for 60 pupils (Steenbrink 2007, 104). The mission was officially opened on 2 February 1916 (Steenbrink 2007, 105). Another small mission post was later opened at Jopu.

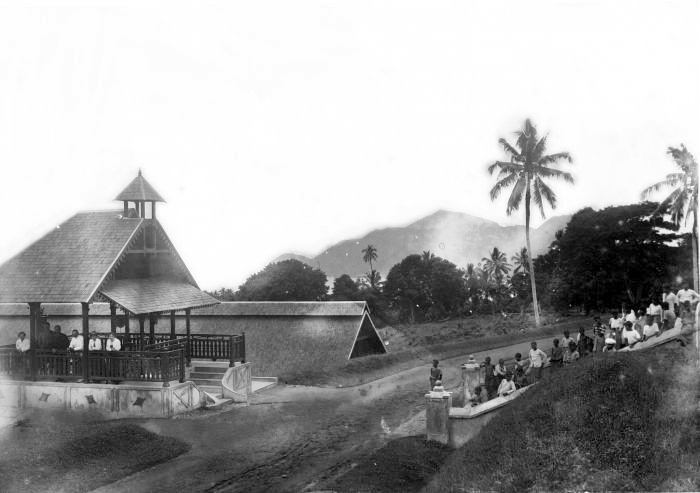

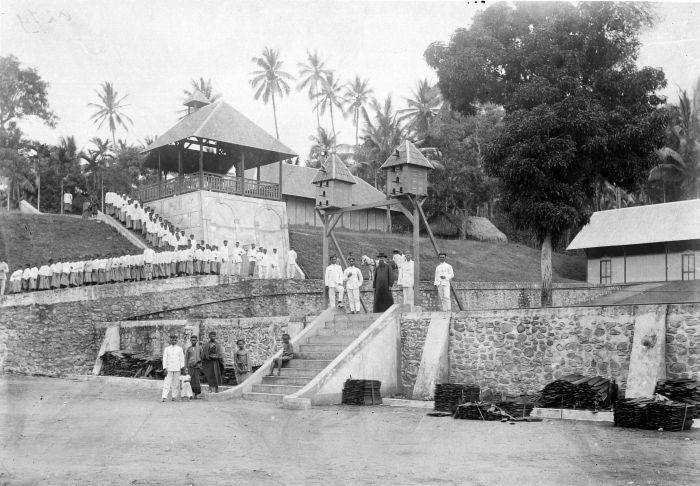

Above and below: the Mission at Ndona, seat of the Bishop of the Lesser Sunda Islands, photographed by Chales Le Roux, Tropenmuseum Amsterdam, Creative Commons

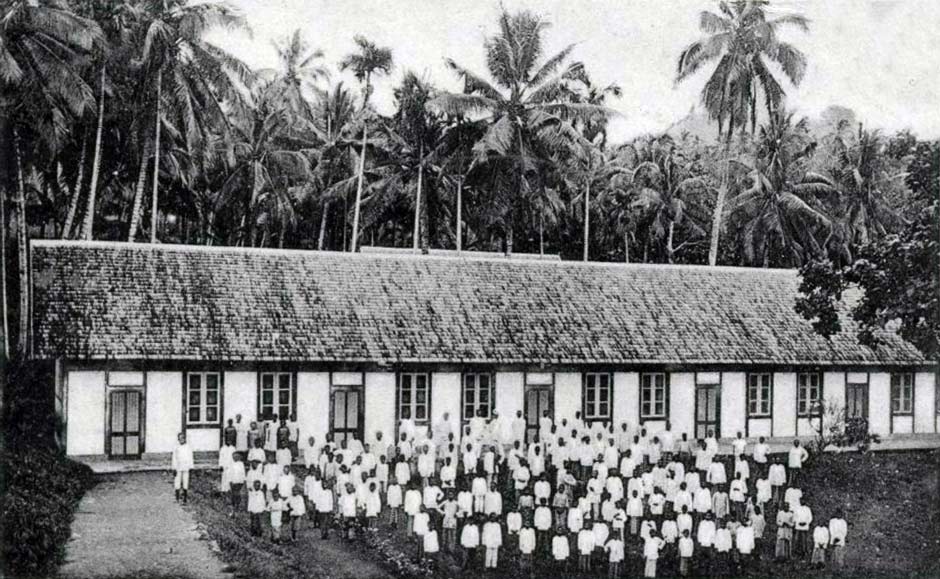

The Catholic school at Ndona, probably photographed between 1915 and 1920

Further administrative consolidation took place in 1915, with the disparate landshaps of Lisé, Mbuli, Nggela, Wolojita and Ndori combined to form the new landschap of Tanah Kunu Lima under Raja Rasi Wanggé and the former landschaps of Ndona, Poe, Sooi, Moke Asa, Wolo Gai and Wena Ria merged to form an enlarged landschap Ndona under Raja Mbaki Mbani. The latter turned out to be a firm supporter of the Dutch.

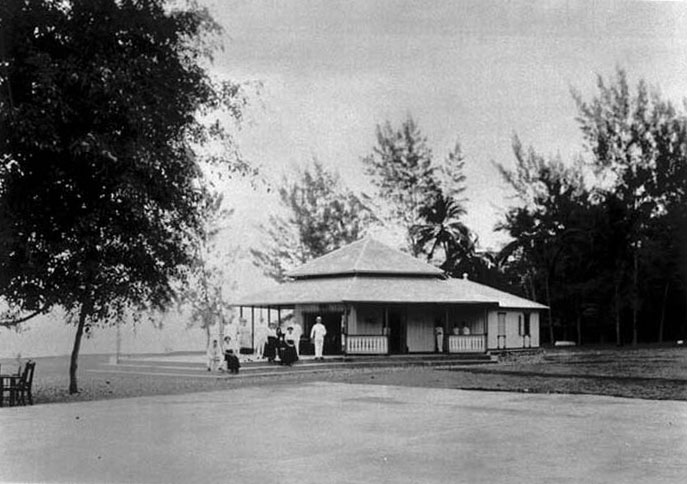

The residence of the Assistant Resident at Ende, around 1915

National Museum of World Culture, Netherlands

The Assistant Resident of Ende, Anton Hens and his family around 1915

He returned to the Netherlands in 1916

Assistant Resident of Ende, Anton Hens, at his desk in Ende

Photographed by Charles Le Roux 1915-16

The Dutch club and tennis court in Ende

Photographed by Charles Le Roux 1915-16

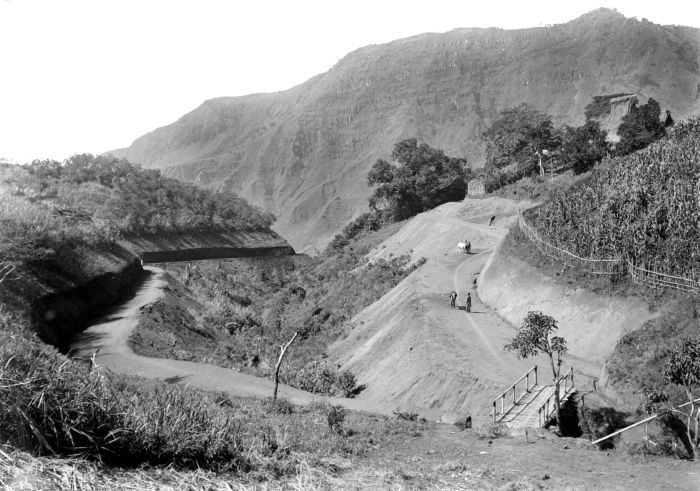

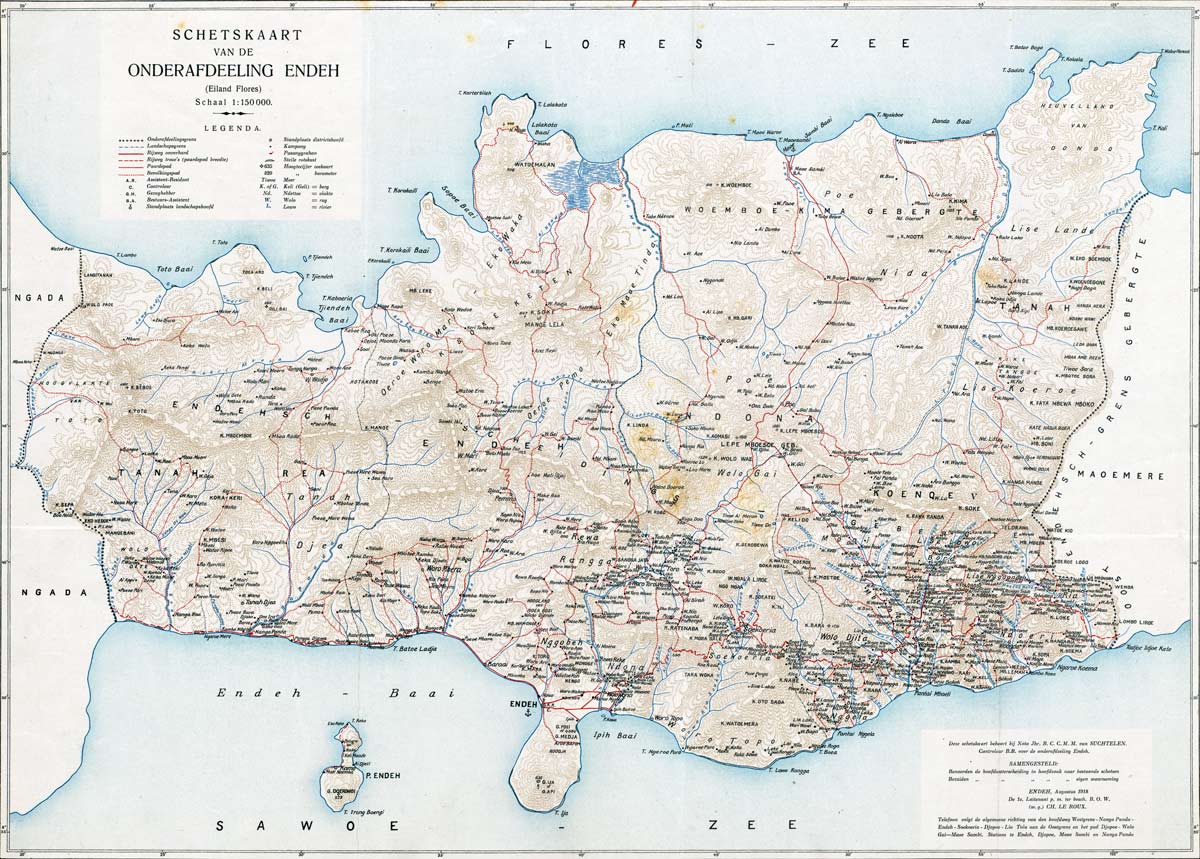

The Dutch had embarked on a programme of road construction following ‘pacification’ and by 1914 many roads around Ende had been completed. Becoming increasingly ambitious they now envisaged a Grand Flores Way that would link towns like Ende to the other main centres on Flores like Larantuka and Labuan Bajo. However this would be a mammoth project – although Flores is just 375km long, the unforgiving landscape would mean that the final Flores Way would be nearly 700km long.

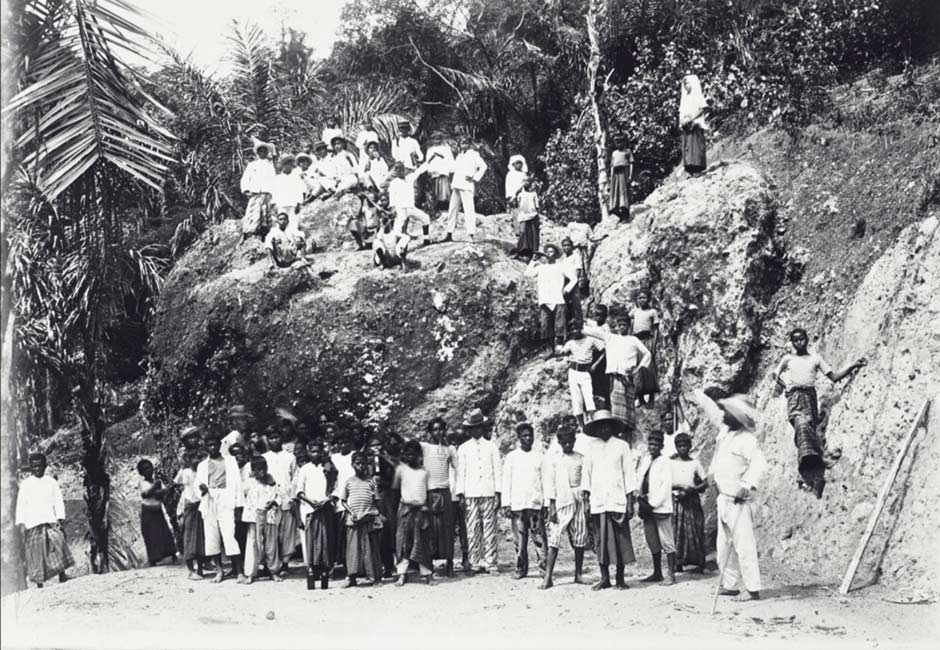

In 1915 the Burgerlijke Openbare Werken (Department of Civil Public Works) of the Netherlands East Indies appointed the civil engineer Charles Constant François Marie Le Roux to oversee this grand trans-Flores road project, a fortunate choice. One of the major challenges would be clearing a route through the unforgiving landscape of Ende, something that require many labourers from the surrounding villages working in lieu of paying taxes. Understandably, this corvée labour caused considerable resentment among the native population.

A former horse trail widened to creat part of the Flores Way to the east of Ende

A huge boulder blocking the planned route of the Flores Way

The 40-metre suspension bridge over the Wolowona River linking Ende to Ndona, an essential crossing on the Flores Way

In 1916 Nipa Do, the traditional lord of the land or tuan tanah of Wolowae district in western landschap Tanah Rea headed a rebellion of local tribes against the Dutch, who had been forced to work or pay tribute for the construction of the Ende-Bajawa section of the trans-Flores highway. The uprising was supressed and Nipa Do was shot.

In 1917 the Rajas of Ende, Tanah Rea, Ndona and Tanah Kunu V were pressurised into signed formal agreements with the Dutch, known as Korte Verklaring or ‘Short Declaration’ – a one-sided agreement designed by van Heutsz in which they recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies, including the payment of taxes.

Administrative structure of Onderafdeeling Ende in 1917

(From van Suchteren 1921, reproduced in Sugishima 2006, 127)

During his four years on Flores Charles Le Roux oversaw the detailed mapping of many parts of the island including Ende. The following detailed map of Onderafdeeling Ende was published in 1918.

A Sketch Map of Onderafdeeling Ende, published August 1918. It shows the route of the Flores Way including two completed sections: one from Nanga Panda to Ndona and the other east of Wolojita

Le Roux also took every opportunity to photograph the locations and villages along the route and the daily life of the local people, becoming increasingly interested in ethnography rather than road construction. His work offers a valuable insight into the appearance of the region at that time.

The Lio mountain village of Roga Ria, located on the Flores Way southwest of Kéli Mutu

Photographed by Charles le Roux, 1915-1919

Kampong Wolotopo in Ippi Bay, Ende

Photographed by Charles le Roux, 1915-1919

During Le Roux’s time on Flores, the talented Dutch artist W. O. J. Nieuwenkamp visited Ende and left us with a fine sketch of Table Mountain, just to the south of Ende town.

Gunung Meja (Table Mountain) from Ippi Bay

Sketched by W. O. J. Nieuwenkamp around 1918

In 1917 the Dutch in Ende started to bring the mountainous areas of central Flores under its administration, a region composed of two rajadoms, Ndona and Tana Kunu Lima (Aoki 2003, 153). One setback was that the Raja of Ndona, Mbaki Mbani, had recently embraced Islam, a serious blow to the local mission. The local bishop blamed the conversion on the perceived pro-Islamic attitude of van Suchtelen and said that it would never have happened under Controleur Hens. Another surprise happened in 1922 when 24 schoolgirls in Nggela embraced Islam and travelled to Ende to stay with a local hajji (Steenbrink 2003, 91). Raja Pius returned the girls to Nggela and their Catholic school.

In May 1923 the Dutch Bishop-elect Arnold Vertraelen SVD arrrived in Ende Bay on a steamer from Kupang and was welcomed by missionaries from Larantuka.

Pua Meno, the Raja of Ende, died in 1923 when his son Hasan was only ten years old. While Hasan was despatched to Kupang and later Surabaya for his education, his nephew, Busman Abdul Rahman, was appointed acting Raja in 1925. Because he was considered to be a temporary head he was said to have had little authority. Despite this he held his position until 1947.

Partially in response to the 1916 rebellion in Tanah Rea and as a way of reducing the cost of administration, the Ende authorities decided to rationalise and reorganise the whole Ende region along ethnic lines. In 1924 the Regency was divided into just two landschap and Rajadoms – Ende and the much larger Lio. During this process landschap Tanah Rea was divided, the district of Wolowae being transferred to Ngada and the residual part merged with the former landschap Ende. Ndona and Tanah Kunu Lima were combined to form the new rajadom of Lio, headed by Raja Pius Rassi Wangge, a staunch Catholic who would head the region until 1941.

During 1924 the Resident of Timor, C. Schultz, paid a visit to Ende with Assistant Resident H. R. Rookmaaker, and was entertained at the local town games.

Visit by C. Schultz, the Resident of Timor, to a sports event in Ende, 1924

The road into Ende town around 1925

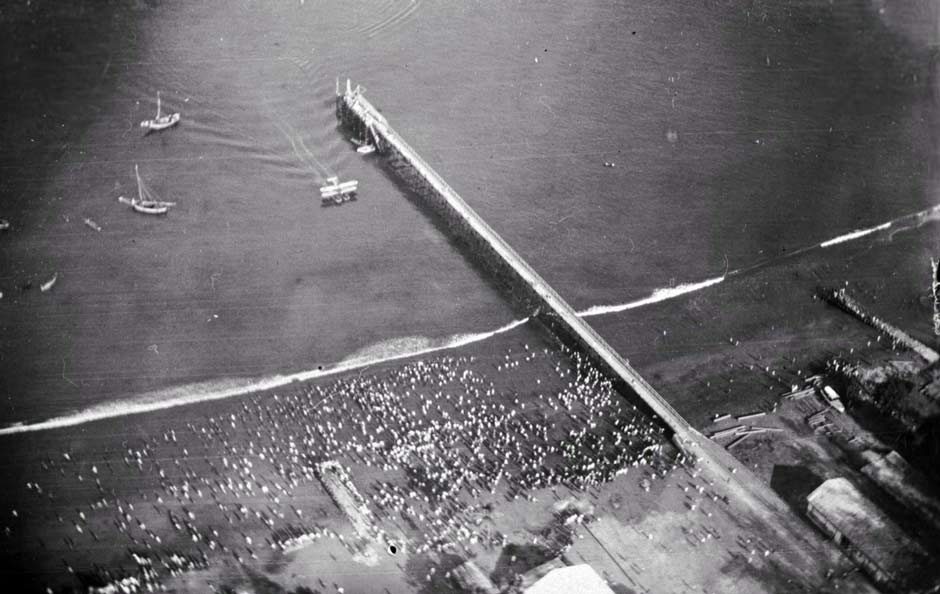

Aerial view of Ende jetty showing the beach filled with crowds watching the arrival of three Van Berkel W-A Royal Netherlands Navy reconnaissance seaplanes in August 1926

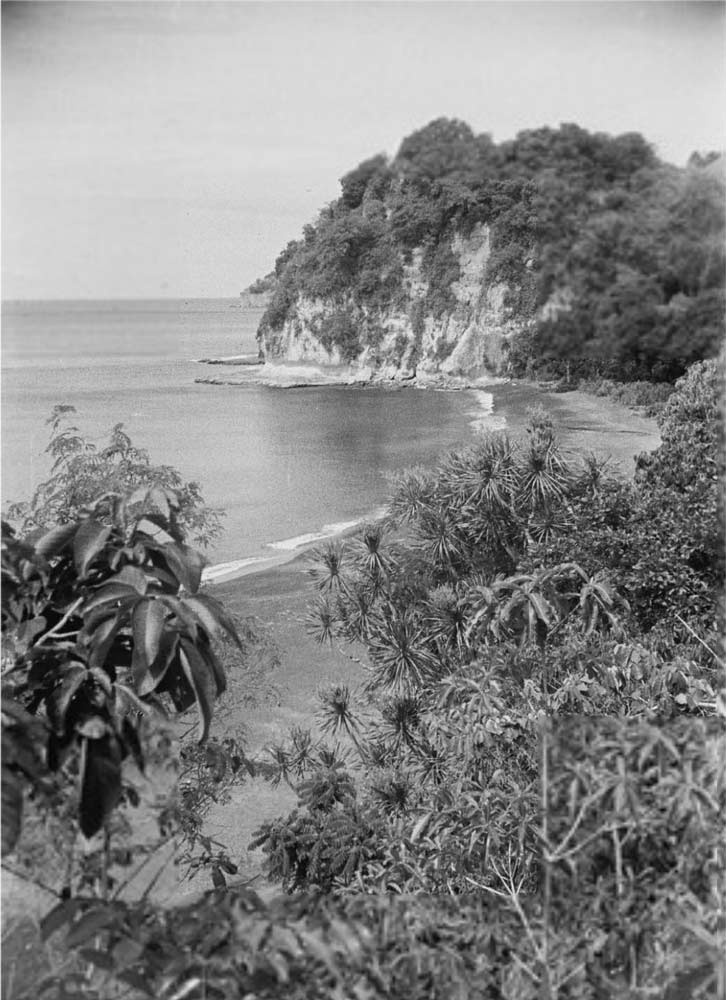

The rugged coastline of Ende in 1927

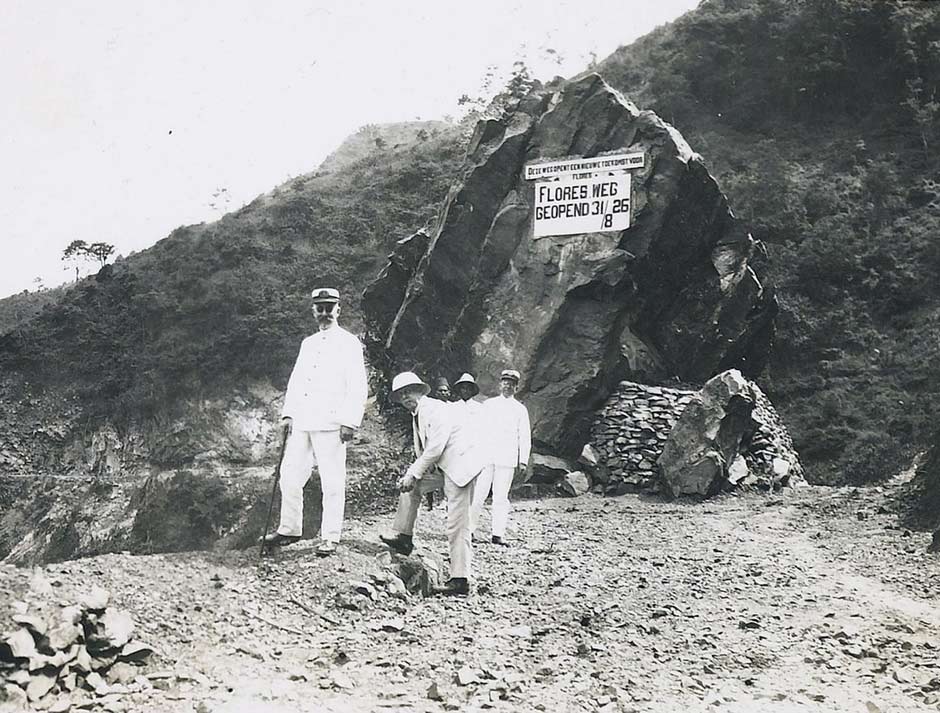

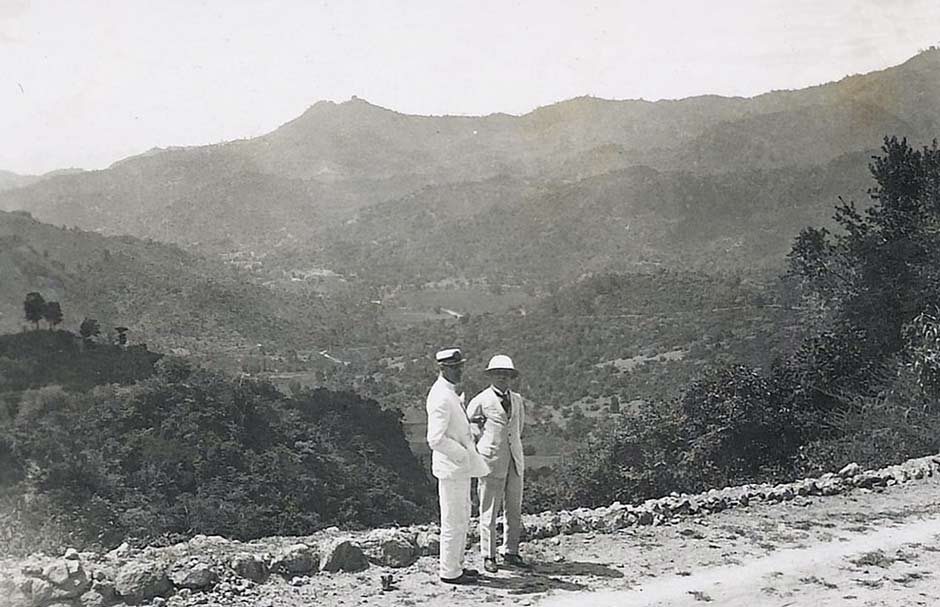

The Resident of Timor, Schultz, returned to Ende again in 1927 on his farwell tour of the Timor dependancies, along with former Resident of Timor, A. J. L. Couvreur, who had also been the first Controleur of Ende in 1906. While in Ende he was driven out to inspect part of the Flores Way, a difficult eastern section of which had only just been opened the previous August.

C. Schultz, the departing Resident of Timor, on his 1927 farewell tour visiting the recently opened Flores Way near Ende with A. J. L. Couvreur and W. K. M. Stibbe

A. J. L. Couvreur (right) and W. K. M. Stibbe (left) on the Great Flores Way near Ende in 1927

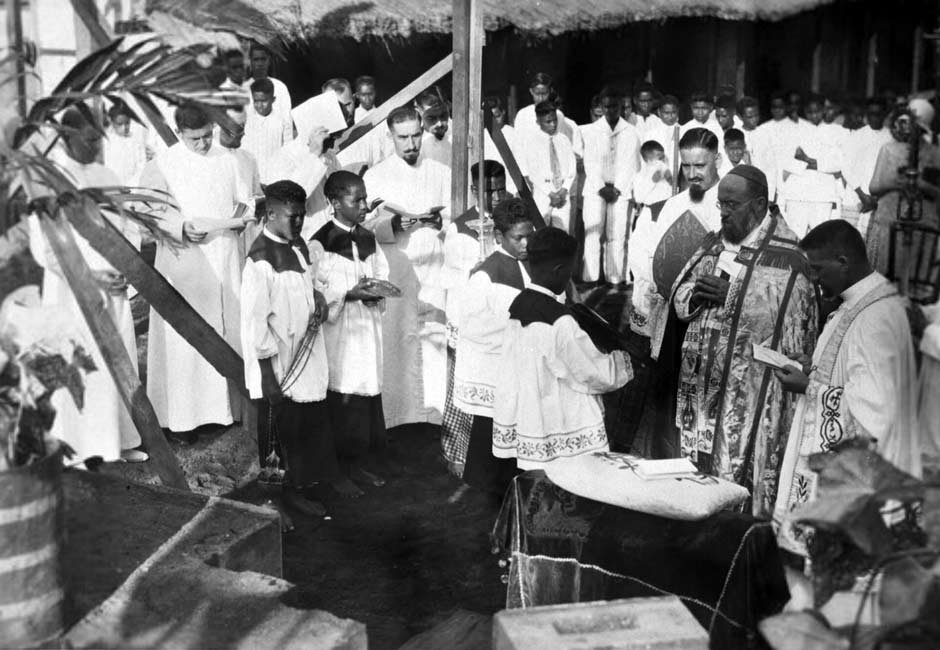

On 18 May 1930, Bishop Verstraelen laid the first stone for the construction of Ende Cathedral Kristus Raja (Christ the King), located close to the harbour. It was almost fully completed in two years. The Bishop consecrated the partially finished Cathedral on 7 February 1932, only to be killed in a car accident on the Flores Way the following month.

Bishop Verstraelen SVD laying the foundation stone for Ende Cathedral in 1932

Residence of the Bishop at Ndona, around 1930

The school at the Ndona mission around 1930

Conversions to Christianity were growing significantly. By 1935 there were 32,275 baptised Christians in the two Rajadoms of Ende and Lio, almost 28% of the total population (Steenbrink 2002, 96).

Yet by the mid-1930s, the population of Ende town was a mere 5,000. Under direct Dutch rule, Ende had gradually declined as a major maritime trading port to an increasingly commercially and politically isolated backwater - so remote that the Dutch chose it as a place of exile for the troublesome nationalist leader Sukarno.

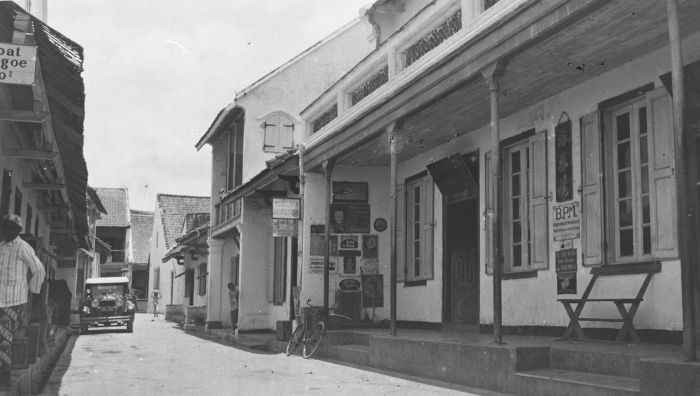

The small Chinese quarter of Ende, around 1930 to 1936

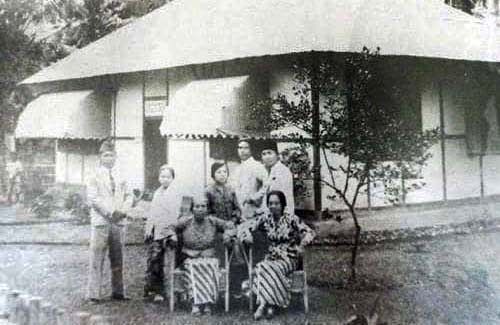

Sukarno and his wife Inggit along with other members of his family arrived at Ende from Surabaya on 14 January 1934, taking up residence in a small house not far from Ende harbour. For an educated man like Sukarno, Ende was an intellectual desert. Sukarno struggled to find any local companions to converse with, complaining that most local people were die-hard conservatives lacking knowledge. He immersed himself in painting and drama, forming a local theatre group called Kelimutu. While exiled in Ende he worked on his mission statement for his Indonesian independence movement, which would eventually be known as the Pancasila. Because of his many discussions with the local SVD priests Bouma and van Stiphout he chose to incorporate the concept of social justice as one of his five principles.

Sukarno with members of his family at his residence in Ende

Sukarno and his wife Inggit with friends in Ende

On 18 October 1938 the Dutch relocated Sukarno and his family from Ende to Bengkulu on Sumatra. We know very little about Ende at his time apart from the fact that detachments of KNIL troops were stationed there in 1940.

Armed KNIL militia at Ende in 1934

Celebrating a holiday in Ende during the 1930s, probably at the home of the Assistant Resident

A motor vehicle on a commercial street in Ende town in 1938

Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

In 1939 the Ende region was affected by exceptionally heavy rainfall, which triggered landslides and floods. A large number of people's houses were destroyed.

The Dutch colonial government in Kupang had been repeatedly annoyed by local conflicts in Onderafdeeling Lio and the behavior of its Raja, Pius Rasi Wangge, who had a reputation for theft and had also been accused of several murders. In 1940 he was ordered to Kupang and put on trial, finally being deposed in 1941 and sentenced to ten years exile in Kupang (Steenbrink 2003, 109; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 243). A large number of Kapitan from Onderafdeeling Lio were punished in a similar manner.

Return to Top

The Japanese Occupation 1942-1945

After the Dutch surrender to Germany on 15 May 1940, the Netherlands East Indies was left isolated and forced to continue as an independent Dutch state remaining committed to the Allies despite lacking any resources to engage in any military operations.

As Japan set its sights on attacking the USA, access to the oil- and resource-rich East Indies became a crucial strategic objective. The Japanese initially attempted to peacefully ally itself with the Netherlnds East Indies but negotiations proved fruitless.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, the Dutch government-in-exile immediately declared war on Japan and within days Japan commenced its carefully planned attack on the East Indies. On the night of 10-11 January 1942, Japanese planes attacked Menado in Sulawesi and Tarakan in north east Borneo.

Although the Netherlands East Indies government had mobilized the Royal Netherlands-Indies Army (KNIL) it decided not to arm Indonesian civilians for fear of armed resistance. The KNIL had scattered garrisons throughout the East Indies but was only equipped to pacify the population, not defend the islands from external attack.

Japanese paratroopers invaded Sumatra in January 1942 and Bali capitulated on 18 February 1942. On 27 February, the Allied fleet was defeated in the Battle of the Java Sea and the following day, Japanese troops landed unopposed at four locations along the north coast of Java undisturbed. On the 9 March 1942 the local KNIL surrendered. Some 42,000 KNIL troops and naval personnel and 25,000 native KNIL troops were taken prisoner.

At the beginning of 1941 the KNIL had 8 brigades on Flores Island, 4 based at Ende and 4 at Larantuka. However in December 1941, the 8 brigades were redeployed to Kupang, leaving Flores Island completely defenceless.

The invasion of the Lesser Sunda Islands, code named Operation S, was led by Rear-Admiral Kenzaburo Hara, Commander of the Sixteenth Cruiser Division. His fleet left Surabaya on 8 May 1942. It consisted of his flagship, the light cruiser Isuzu, the minelayer Shinko Maru and the troop transporter Shingu Maru, carrying elements of the Third Battalion of the 47th Infantry Regiment of the 48th Infantry Division, under the command of Major Ikumi Miyaji, along with the minelayer Wakataka, carrying a battalion of the First Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force.

The demilitarised Watataka in 1947. It had only been launched at Kobe in 1941.

After deploying troops on Lombok, Surabaya and Sumba, the Japanese made their first landing on Flores Island at Reo on 13 May 1942. Two days later some of the fleet anchored off Ende, waiting for additional Japanese troops to arrive. The Special Naval Landing Force arrived on 17 May and faced no resistance. One infantry company, a communication unit, an engineer unit, a transport unit, a medical unit and a paymaster unit went ashore to take control of the territory.

At that time the majority of Europeans left on Flores were Dutch, German and Austrian Catholic and Protestant missionaries. The naval commander ordered the SVD Bishop Henry Leven to bring all of his missionaries and sisters to Ende to be investigated for possible internment. Many of the Dutch women were raped by the occupying forces (Tanaka 2002, 62). On 15 July 1942, 114 missionaries and 34 sisters, the majority Dutch, were picked up from Ende harbour and taken to an internment camp at Parè-Parè on Sulawesi, along with other Europeans from Sumbawa and Sumba.

Just eleven enemy missionaries were left to continue with their religious duties, including Bishop Levens at Ndona and the director of Ledalero seminary, plus three German SVD priests.

The Japanese sought support from the local Rajas and even released Pius Rasi Wangge from exile in Kupang, returning him to Flores as an adviser to the Japanese administration. A European priest claimed that this made it possible for him to resume his old ways of extorting the local population (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 243).

Pius Rasi Wangge from Wololele, eastern Lio

At the start of 1943 Tasuku Sat-o, a lecturer at the Naval College in Etajima was appointed Commander of the Naval Guard Corps on Flores Island. He was first flown from Haneda to Taipei via Manila along with the Catholic Bishop Yamaguchi of Nagasaki and his secretary Father Michael Iwanaga, and then from Taipei to Makassar along with the Catholic Bishop Aloysius Ogihara of Hiroshima. In Makassar Tasuku Sat-o received his orders from Admiral Furomei, including the instruction to round up the remaining enemy missionaries and ship them to Makassar for internment.

A few days later a seaplane from Makassar carrying the new Naval Commander, Tasuku Sat-o, along with Bishop Ogihara landed at Ende harbour where they were warmly welcomed by the local people. The Commander was billeted at the barracks on Beach Avenue, not far from the beach in Ende.

Bishop Paul Aijirō Yamaguchi

Several weeks later another seaplane arrived at Ende carrying a Japanese Catholic Mission, composed of Bishops Yamaguchi and Fathers Michael Iwanaga and Philip Kyuno. They were welcomed by Bishop Leven, Bishop Ogihara and some of the local Dutch missionaries. It seems that the Japanese command in Tokyo recognised the importance and stabilising influence of the Catholic religion on Flores, and had despatched this mission to support the local Catholic Church. The Japanese were well aware that persecution of Catholics in the distant past had led to the bloody Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-38.

The Japanese Mission warned Commander Tasuku Sat-o that removing the established priesthood might risk instability among their Christian supporters. They also informed him that only the Pope could remove Bishop Leven and replace him with Bishop Yamaguchi. With their support Tasuku Sat-o was able to overrule its initial orders and allow the remaining SVD missionaries to continue their work on Flores.

Tasuku Sat-o remarked that Ende seemed like a million miles removed from the stern reality of war (Sat-o 1957, 17). He toured both East and West Flores in a requisitioned Chevrolet without incident. The Japanese Navy had rallied local support by promising them independence from Holland once the war was over. However Tasuku Sat-o’s sanitised account of life on Flores under the Japanese fails to mention anything negative abou the occupation, including the Flores internment camps and the use of slave labour to construct airfields.

On 9 May 1943, more than 2,000 Dutch and other Europeans POWs arrived by sea from Java in three ships, brought in as labourers for the construction of airfields. Their first task was to build three POW camps – Camp Blom to the east of Maumere, Camp Reyers and the hospital/quarantine Camp Wulff. In June, July, and August 1943 more than 300 POWs were installed at a labour camp near Talibura, some 60 kilometres east of Maumere, where they were used to build an auxiliary airfield. Work proceeded rapidly and by early November 1943 the Maumere-East airfield was ready for operation. After its completion the POWs were set to work in the harbour and on two other small airfields near Maumere.

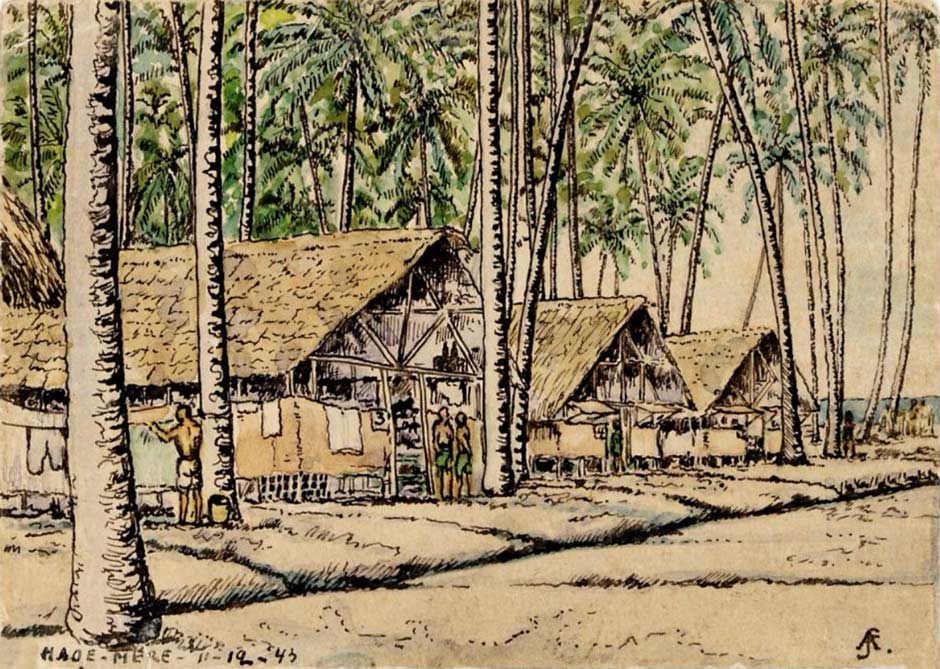

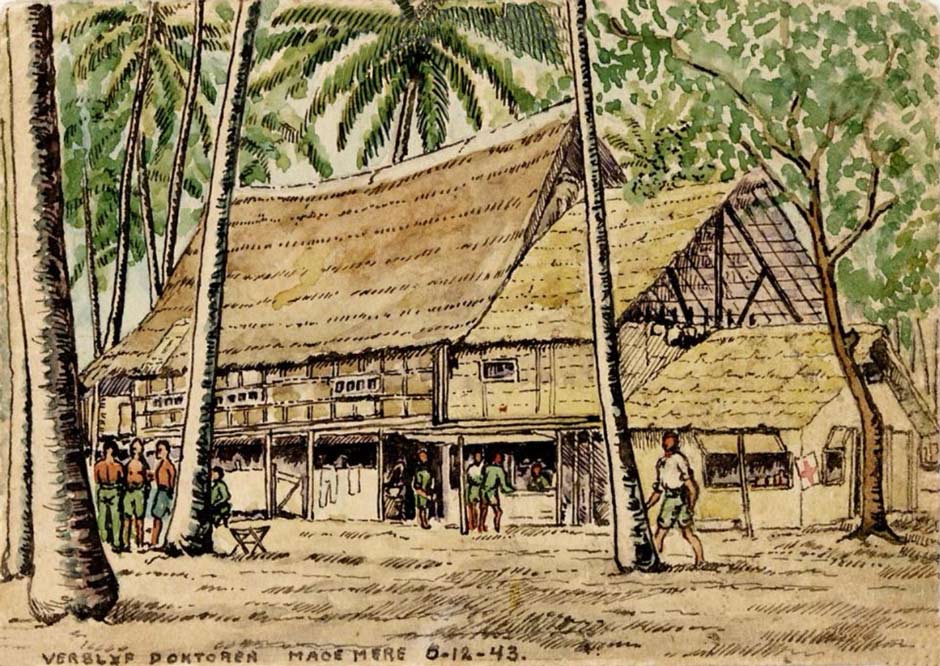

A painting of the POW camp at Maumere in 1943 and below the camp clinic

POW sketch of the residence for the medical staff at Camp Blom, Maumere

In September 1943 a new Civil Administration office was ceremonially opened in Ende. The Controlled invited the Raja of Ende and local clan chiefs to the opening ceremony, promising them national independence once the days of hardship were over. In February 1944, Admiral T. Fukeda travelled from Makassar to Commander Tasuku Sat-o’s naval headquarters in Ende. After discussions he supported the local commander’s view that the Japanese mission should remain at Ende and the European priests should be allowed to continue their duties. He even requested that the missionaries that had been interned should be returned to Flores, but his proposal was turned down. Instead he asked the Japanese Mission to stay longer on the island.

Tasuku Sat-o’s account makes no mention of the hardships endured by the local population. For example there is no mention of the young Javanese girls shipped to Flores as ‘comfort women’, cruelly forced to serve at least two Japanese soldiers a day (Tanaka 2002, 79). Many died because of mistreatment by the Japanese. The only negative thing that Tasuku Sat-o mentions is that while in Larantuka during September 1943 he found that the Chinese shops along one of the two main roads were almost empty because of the war and lack of materials (Tasuku Sat-o 1957, 61).

By now allied aircraft were making bombing runs across the island. In January, May, and June 1944 large groups of POWs were sent back from Maumere to Java, and on 10 August Camp Blom was evacuated. The last group of POWs left Flores on 12 September 1944. A total of 214 POWs from the Flores camps did not survive their ordeal.

At the end of January 1944 Commander Tasuku Sat-o’s headquarters were relocated to Waingapu on adjacent Sumba Island. When he returned to Ende in May 1944 he saw that it had been just as badly bombed as Waingapu (Sat-o 1957, 114).

In early 1944 the Japanese had stepped up their preparations for an attack on Australia. The Japanese Naval Guard Corps headquarters in Ambon was relocated to Ende as the 24th Base Force and large numbers of Japanese troops began to be assembled around Maumere. In response the Allies increased the intensity of their air raids on Flores and between June and November 1944 conducted twenty raids on Maumere, Ende, Ruteng and Waewerang. Ende town was heavily bombed by twelve B-17 aircraft on 14 November 1944 and the Cathedral was hit and burned down (Sat-o 1957, 112). The churches in Ruteng and Waewerang were damaged, some 200 civilian houses and office buildings were destroyed and 80 people were killed (Petu 1966, 47).

In September 1944 Admiral Fukeda was recalled to Japan and the naval headquarters in Ende were closed. Tasuku Sat-o returned to Waingapu.

During 1945 the allied air raids became more daring and the local population on Flores became increasingly concerned. Maumere had been completely destroyed and much of Ende was left in ruins. Taksuku Sat-o wrote that it was thanks to the good influence of the Japanese bishops and priests on Flores that despite the bombings, public order on the island had been maintained (Sat-o 1957, 121).

Bomb attack on four Japanese motorboats on Flores Island, 11 August 1945

Although atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, the attacks on the Japanese forces on Flores continued. It was not until 15 August that Emperor Hirohito finally surrendered to the Allies.

On 9th August 1945 a Japanese military plane had flown the leaders of the independence movement, Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta and Dr Radjiman Wediodiningrat, to Saigon, where they were taken to Dalat to meet Field Marshal Terauchi Hisaichi, Commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army. They were unaware that just hours earlier, the USA had dropped its second atomic bomb on Nagasaki while Soviet forces had invaded Manchuria. They were told that Japan would at last recognize Indonesian independence. The leaders returned to Jakarta on 14th August and on the following day Japan capitulated. On 17th August Sukarno was encouraged to announce the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence or Proklamasi Kerdekaan Indonesia and the 'five principles' that he had formulated while in exile in Ende.Return to Top

Post-War Developments 1945-1949

Earlier in July 1945, General McArthur, Commander-in-Chief U.S. Army Forces Pacific, had delegated responsibility for all operations in the southwest Pacific south of the sixteenth parallel to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander Southeast Asia. Because of wartime Anglo-Dutch agreements, the British had had been left with an obligation to restore the status quo in the East Indies by helping the Dutch reoccupy their former territories. British Indian forces would take responsibility for initially gaining control of Java and Sumatra while Australian forces would take responsibility for occupying eastern Indonesia.

The first Australian troops arrived in Kupang on 2 September 1945 under the command of General Sir Thomas Blarney (Ardhana 2005, 328). Colonel C. C. de Rooy, the leader of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA), left Darwin on 7 September 1945 with 37 Dutch NICA officers and supporting troops, and arrived in Kupang on 11 September 1945 (Ardhana 2005, 349). He was accompanied by the Resident of Timor, C. W. Schuller and the Controleur R. Westerbeek. That very same day on board HMAS Moresby, moored just offshore from the ruins of Kupang, Colonel Kaida Taitsuchi signed the formal surrender of the Japanese forces on Timor, surrendering his sword to Brigadier Lewis H. Dyke, Commander of the Australian 33rd infantry brigade.

Later on 26 September, Lieutenant General K. Yamada, commander of the Japanese 48th Division and eight of his senior staff flew from Sumbawa to Kupang and on 3 October formally signed the unconditional surrender of the Lesser Sunda Islands in front of Brigadier Lewis G. H. Dyke on a newly made parade ground in Kupang (Farram 2004, 217).

Major J. M. Baillieu with Brigadier Dyke about to read the surrender document to Lieutenant General Yamada in Kupang on 3 October 1945

Lieutenant General Yamada signing the surrender document in Kupang on 3 October 1945 as Brigadier Dyke looks on

NICA troops under the leadership of Colonel C. C. de Rooy quickly took over the civil administration of West Timor and the neighbouring islands, re-assigned employees from the pre-Japanese era.

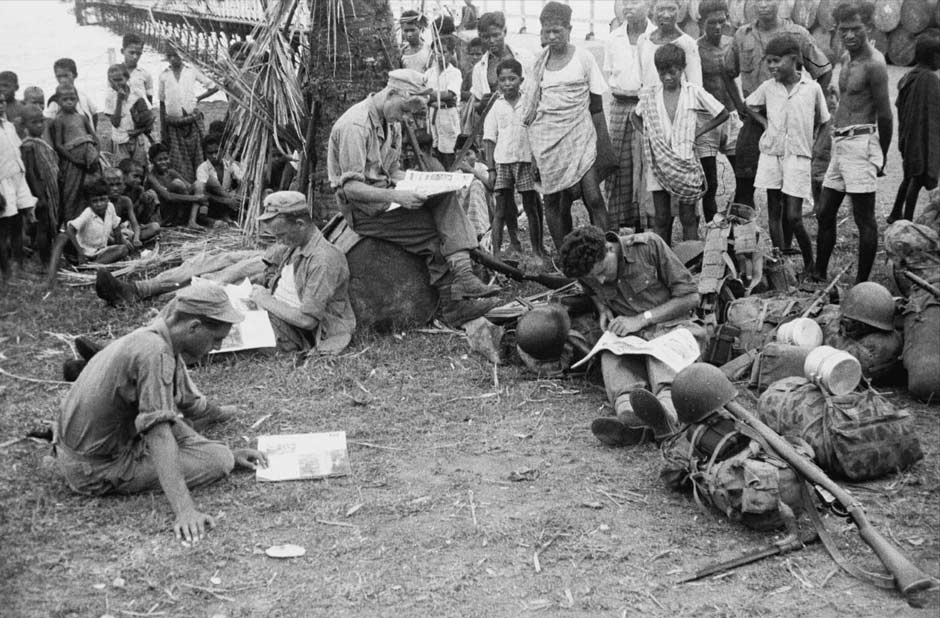

Between 13 and 30 October 1945 Schuller and Westerbeek conducted an inspection trip of Flores, Sumbawa and Sumba (Ardhana 2005, 349). Australian forces occupied Flores on 4 November 1945, receiving a mixed reception. In Maumere, Australian and NICA personnel received a warm welcome but elsewhere there was disappointment that the Dutch and not the Australians would be taking back control (Farram 2004, 218).

In December 1945 all the Japanese throughout the Lesser Sunda Islands were despatched to a concentration camp located at Robok on Sumbawa Island (Tasuku Sat-o 1957, 120).

While the Dutch faced no major obstacles in reasserting their control over most of the eastern area previously occupied by the Japanese Navy, including Flores, this was far from the case in the west. Although a small British intelligence unit had been parachuted into Jakarta (the new republican name for Batavia) on 2 September it was not until 15 September that two cruisers, one British and one Dutch, arrived with troops and a group of NICA officials. The British were surprised that the island was firmly under Republican pemuda control and that anti-Dutch feelings were widespread.

An alarmed Lord Mountbatten at his headquarters in Ceylon realised that any military campaign to restore Dutch control of Java or Sumatra would be disastrous. Much to the surprise of the Dutch, he refused to allow Dutch troops to reoccupy Java and Sumatra and confined British activity to just Jakarta and Surabaya. Dutch forces would only return after the departure of the British in November 1946.

In Jakarta the Acting Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, Hubertus van Mook, responded to this situation on 6 November 1945 with a radical proposal. The Netherlands would recognise Indonesian national aspirations and would create a central government composed of

- a democratically elected body with a substantial Indonesian majority and

- a council of ministers headed by the Governor General representing the Netherlands, which would govern internal affairs.

At the Malino Conference in Sulawesi held in July 1946, representatives from Borneo and eastern Indonesia backed Dutch proposals to create a federal United States of Indonesia composed of the Republic of Indonesia on the one hand and the states of Borneo and the Greater Eastern State (Negara Timur Raya) on the other, closely linked to the Netherlands.

In November 1946 the Dutch and the republican leadership negotiated the Linggardjati Agreement, which accepted the existence, although not the legality, of the Republic of Indonesia in Java, Madura and Sumatra. Following a further conference in Denpasar, the Dutch renamed the Greater Eastern State on Christmas Eve 1946 as Eastern Indonesia, Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT). Governed by the Dutch from Makassar, it encompassed the Lesser Sunda Islands, including Flores, as well as Sulawesi and Maluku (Ricklefs 2008, 276). Flores would become one of thirteen regions ruled by a parliament with seventy delegates, just three from Flores – Jan Rats SVD representing the council of Rajas along with Adrianus Conterius SVD and Louis E. Monteiro.

The Dutch state of Negara Indonesia Timur, formed in 1946 and dissolved in 1950 (Wikimedia Commons)

In the meantime the Dutch reinstated their administration in Ende during 1946. J. E. C. Ezerman who had been secretary to the Resident of Timor, Fokko Jan Nieboer, prior to the war was installed as the Assistant Commissioner for Flores operating from headquarters in Ende (Forth 2021, 14). He would remain in this post until 1949.

During 1946 and 1947 the Dutch authorities held trials in Kupang for Japanese officers and Indonesians accused of war crimes or collaboration with the enemy. One high profile case was that of the former Raja of Onderafdeeling Lio, Pius Rassi Wangge, who was found guilty of inciting rebellion against the Dutch and collaboration with the enemy during the Japanese occupation of May 1942. He was executed in April 1947.

While the republicans had gained control on Java, Sumatra and Bali, the Christian island of Flores had remained relatively untouched by the independence movement. However things were changing fast – in November 1946, nine of the Rajas on Flores formed an island-wide council called the Flores Federasi with the Raja of Sikka as its chairman.

During 1947 Raja Busman Abdul Rahman died and was succeeded by the young Raja Haji Hasan Aroeboesman. He was to become the very last official Raja of Ende, only ruling until 1950. During his short reign he assigned a large plot of land in Ende for the construction of a church.

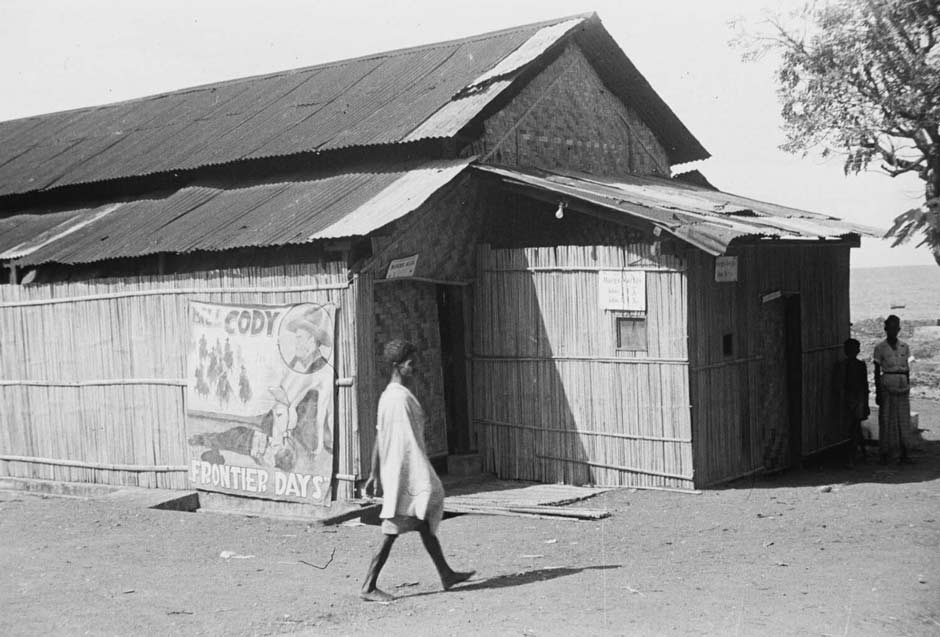

We have been left an important photographic portrait of Ende town in February 1949 by the 28-year-old Dutch military photographer Cees Taille. It shows a modernised town with wide streets lined with drainage channels, colonial buildings, bustling markets and even a small cinema displaying and advertisement for the 1934 American Western, Frontier Days, starring Bill Cody as an agent for Wells Fargo!

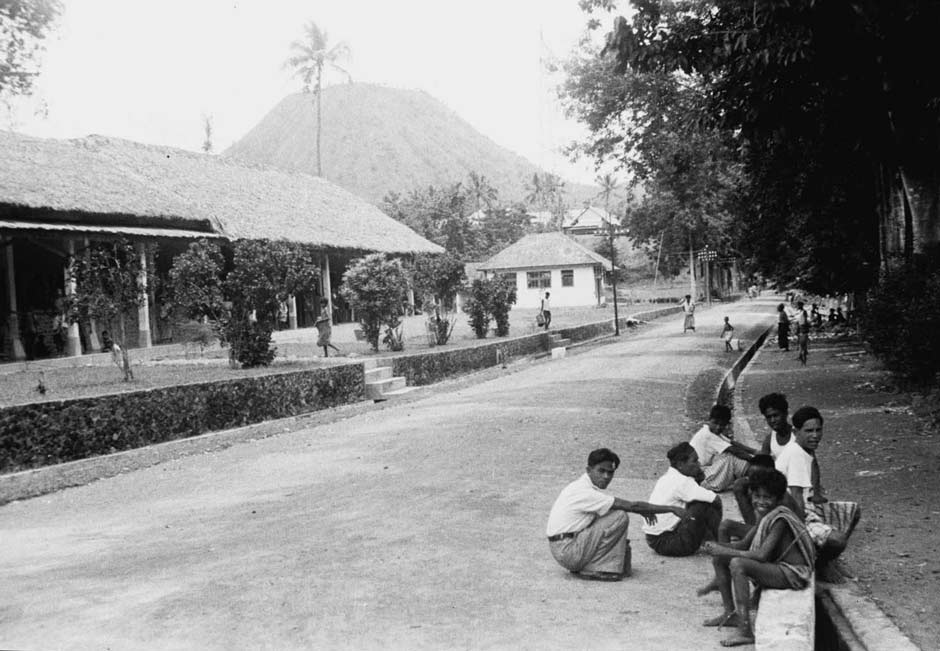

Ende street not far from Table Mountain

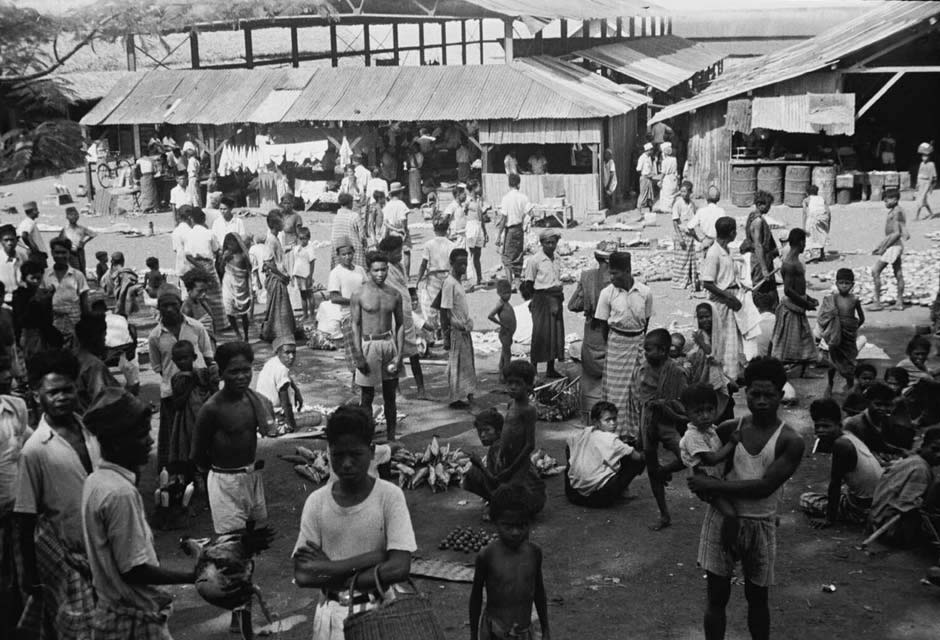

Market in Ende close to the harbour

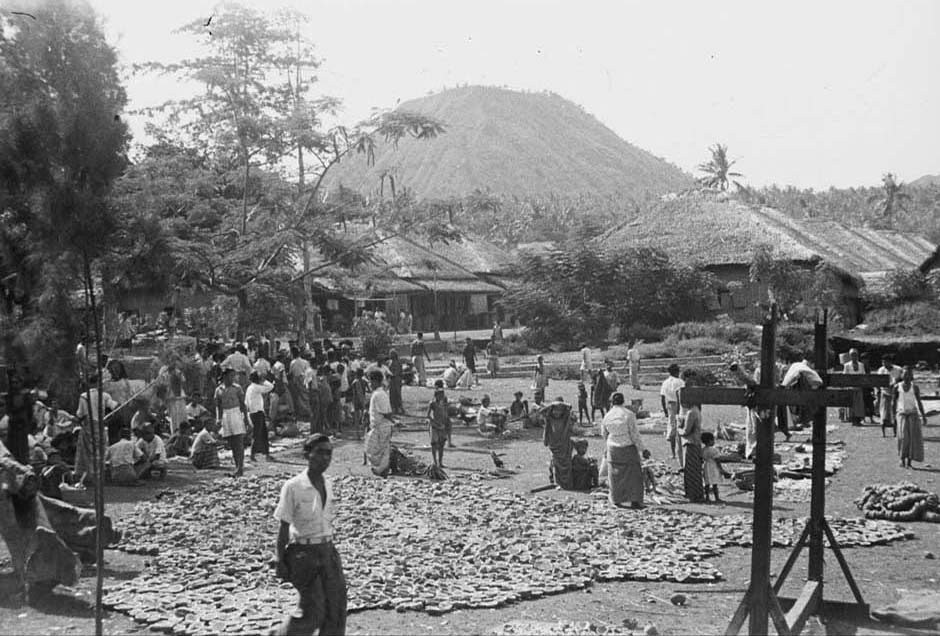

Open market close to Table Mountain selling copra

A group of schoolchildren with their teacher in Ende town

A simple cinema in Ende advertising Frontier Days

It was the last year of Dutch colonial rule and Holland had only just launched Operation Crow, occupying all of the Republican-held cities on Java and Sumatra. Dutch soldiers were manning defences in Ende harbour and were very much in evidence on the streets of Ende.

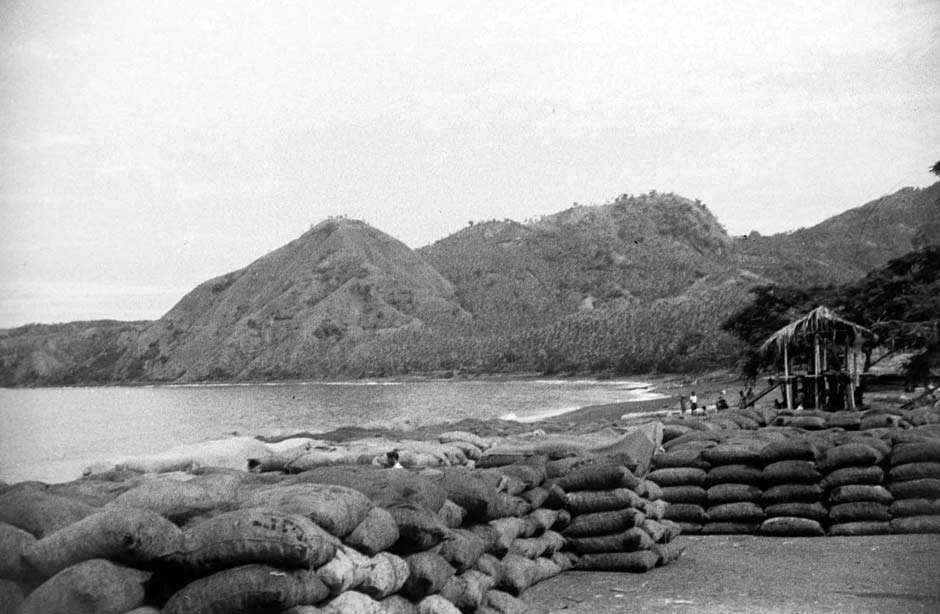

Dutch beach defences in Ende Bay

A Dutch Grenadiers Patrol at Ende jetty waiting for a boat to take them back to their base on Timor

A street scene in the Ende region

The coast of Ende Bay in 1949

In March 1949 the Residency of Timor was renamed the Timor Archipel and moves were undertaken to decentralise governance by transforming Flores, Sumba and Sumbawa into autonomous regions (Farram 2004, 251). In May 1949 the Prime Minister of NIT appointed the Raja of Sikka, Don Thomas Ximenes da Silva, to the position of District Head of Flores (Lewis 2006, 251).

Return to Top

Ende following Independence

A Dutch-Indonesian round table conference was finally held in The Hague from 23 August 1949 to 2 November 1949, between the Republic, the Netherlands, and the Dutch-created federal states. The Netherlands agreed to recognise Indonesian sovereignty over a new federal United States of Indonesia. It would include all of the territory of the former Dutch East Indies, with the exception of Netherlands New Guinea. The Netherlands finally transferred sovereignty to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia Serikat) on 27 December 1949. This only lasted until 15 August 1950 when the Republic of Indonesia was declared. On 17 August 1950 the State of East Indonesia was dissolved and all of its territories merged into the Republic of Indonesia with a centralised government.

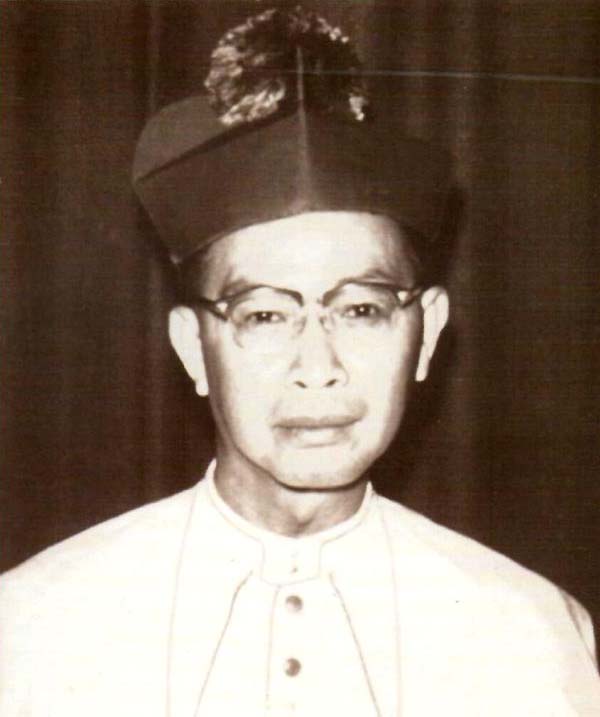

On Flores, Louis E. Monteiro was installed in Ende during 1950 as the island’s first District Head or bupati with William Lalamentik as his Secretary until 1951.

Bupati Louis E. Monteiro

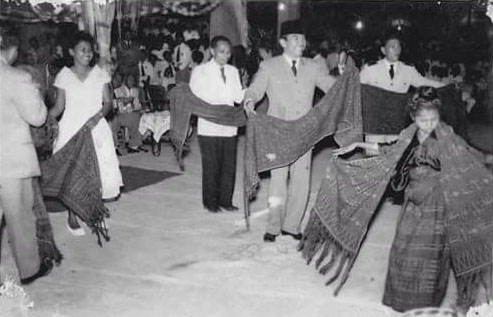

It did not take long for the first President of Indonesia, Sukarno, to return to Ende, his place of exile. He arrived in 1951 and returned again two more times – in 1954 and 1957. Sukarno loved Ende, it being the place where he first envisioned the future state of Indonesia. He is reported to have stated 'ja'o ata Ende' (I am an Ende person).

President Sukarno with Lio dancers at a welcoming celebration in Ende in the 1950s

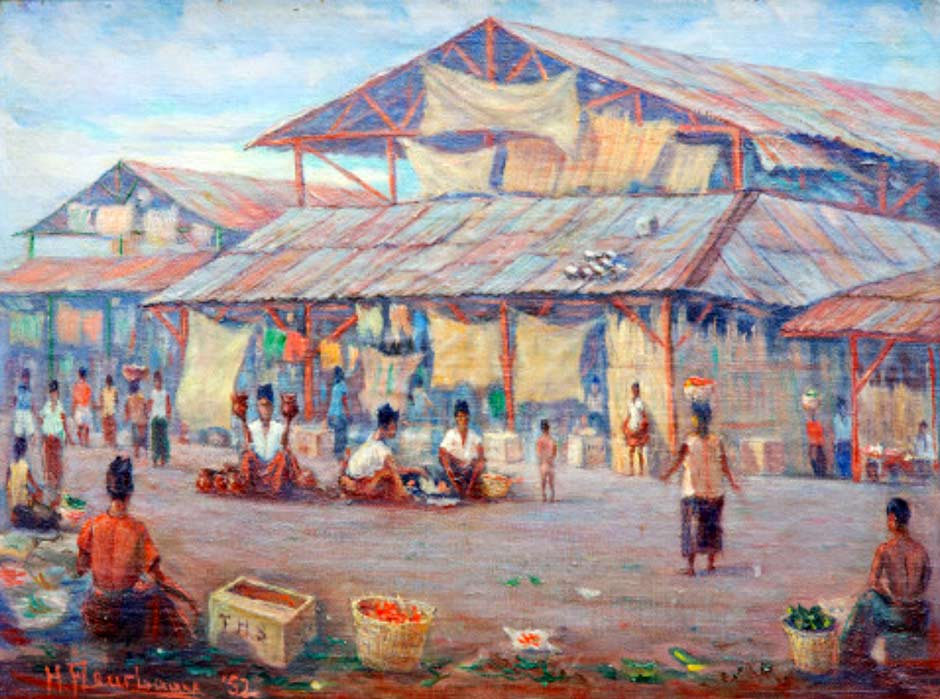

We have been left a painting of the covered market in Ende town at this time painted by Hendrik Fleurbaay, a former sea captain and the head of a Dutch shipping company.

Pasar te Endeh painted by H. Fleurbaay in 1952

In 1953 District Head Monteiro laid the first stone for the first Protestant church in Ende, which opened for use in 1959 although was not officially inaugurated until 1970 (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 286). At that time the small Protestant community in Ende were still considered as outsiders by the Catholic priesthood.

In 1957 the Province of Nusa Tenggara, the Lesser Sunda Islands, was divided into three level 1 autonomous provinces: Bali, West Nusa Tenggara and East Nusa Tenggara. Later, on 9 August 1958, Indonesian law No. 64 permitted the formation of level 2 regions. East Nusa Tenggara (Nusa Tenggara Timur or NTT) was sub-divided into twelve kabupaten or regencies along with the City of Kupang, the centre of provincial government, which had regency-level status.

Flores itself was split into five regencies: Manggarai, Ngada, Ende, Sikka and East Flores. Monteiro served as the head of Flores Island until the five regencies were inaugurated on 14 December 1958 with Mauritz Geradus Winokan appointed the first Acting Regent of Bupati of Kabupaten Ende. Winokan became the Regent of Ende in 1961 after successfully passing his nomination trial.

Mauritz Geradus Winokan and his wife Anna

In January of 1961 Bishop Gabriel Manek SVD was appointed the first Archbishop of Ende, based in Ndona. Ende was the largest Catholic diocese on Flores. In March, a magnitude 6.5 earthquake 44km north of Ende caused damage throughout the island of Flores, especially in the Ende region.

Gabriel Manek SVD, a native of Timor

Winokan was a populist leader who faced up to the challenge of integrating the two ethno-linguistic regions of Ende and Lio into one political unit. He pioneered the formation of the initial six kecamatan or sub-districts of Ende Regency: Nangapanda, Detusoko, Ende, Ndona, Wolowaru and Magekoba. Another priority was the education of local children and the increase in the number of schools. Winokan also recognised that the three crater lakes of Kéli Mutu could be the foundation of a local tourist industry.

However Winokan's development efforts across the regency were interrupted by the kidnap and assassination of six senior military leaders by a disaffected army faction in Jakarta on the evening of 30 September 1965 and the swift response of Major General Suharto and his military supporters. After ousting Sukarno, Suharto immediately launched a propaganda campaign, painting the assassinations as an attempted coup by the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI). The army began a systematic massacre of the very large but mostly unarmed Communist opposition, at that time the world’s biggest non-ruling Communist party.

It is impossible to know the extent of PKI support in Ende or across Flores but it was likely to have been at a very low level compared to Java. Nevertheless, many Catholic priests believed that there were branches of the PKI in the Muslim community of Ende town and in some of the neighbouring villages where Islam was strong (Webb 1986). At the start of 1966 the army began a witch-hunt against communists across NTT. The Javanese army commander in Ende, a devout Muslim, ordered young Catholics and Muslims to join together to kill all known or suspected communists. However, despite its anti-communist stance, the Catholic clergy took a strong stand against such killings. The highly respected Archbishop Manek condemned the whole affair, leaving the commander to fall back on his own soldiers to lead the purge (Webb 1986).

Suspected PKI sympathisers being rounded up by the army and some of its civilan supporters

In Ende town many suspected communists were arrested. One report suggests that they were brought out of prison daily, twenty at a time, and beheaded (Farram 2010). Sometimes a head was left displayed in the town’s central square (Sulzberger 1966; King 1966). One high profile event was the hideous public burning of John Dimu, a fervent local PKI supporter, at Tanjung, the peninsula to the south of Ende town (Farram 2010). The army advertised the killing the day before so that people could gather to witness the event. Dimu was dragged to the location behind a truck and placed inside a stack of tyres soaked in petrol.

Winokan was elected for two four-year terms but died of cancer towards the end of his second term on 10 July 1967. He was buried at Ende Cathedral. To fill the temporary vacancy, the then Governor of NTT, General El Tari, appointed Hendrikus Antonius Labina as the Acting Regent of Ende. His tenure was short. On 2 September 1967 Haji Hassan Aroeboesman, the last Raja of Ende, was inaugurated as the next Regent of Ende by Governor El Tari.

Bupati Haji Hassan Aroeboesman, seated centre, alongside members of his administration

Under Hasan Aroeboesman’s leadership, work began on the construction of Ipi Ende Airport on the plain between Gunung Wongge and Gunung Meja (Table Mountain). However on 27 January 1969 the nearby Mount Iya volcano erupted sending a column of smoke and ash 5km high. Although only a few people died, one village was destroyed and seven others were partly destroyd. In Ende city, a total of 177 houses, 6 mosques and 3 schools collapsed, and a number of other buildings were heavily damaged.

The eruption of Mount Iya in 1969

By 1970, most of the rural population of Ende Regency had converted to Catholicism.

In the 1973 elections, Governor El Tari insisted that 36-year-old Herman Josef Gadi Djou (popularly known as Ema Gadi Djou or just Ema) should stand as the candidate for Golkar, despite being reluctant to do so. He became the youngest Regent of Ende and served for ten years, focusing his administration on improving education. One of his achievements was the founding of the private University of Flores, based in Ende.

During his second year in office, Ippi Ende Airport commenced operations and was later renamed the Haji Hasan Aroboesman Ende Airport.

In 1988 heavy rainfall triggered floods, landslides and debris flows across the Ende region. The entire village of Rowo Reke was destroyed, claiming the lives of 48 people. Meanwhile flash floods destroyed parts of Aeisa village, 2 km northwest of Ende. The access road between Ende and Detusoko was closed at eleven points due to landslides and debris flows.

On 12 December 1992 Ende Regency and the rest of central and eastern Flores was rocked by a major 7.8 magnitude earthquake in the Flores Sea, which caused widespread damage to both urban and rural buildings. Some mountain Lio villages, such as Saga, were badly affected by landslides and rock falls.

Clearing building damage in Ende following the earthquake

As the 1990s unfolded, conflicts began to arise between different ethnic-religious groups in Ende and elsewhere across Flores. As previously explained, while most of the rural population throughout Ende Regency were Catholic, Ende town had been the home to a large community of Muslims, many originating from Makassar. As such, the majority of the Bupati of Ende’s staff was Muslim, so Catholic political representation was minimal.

Many incidents were sparked when recent immigrants, especially from Java, transgressed local traditions or married local Christian women and encouraged them to convert to Islam. The most common cause of local violence was the deliberate desecration of the sacred host in front of the Catholic congregation at public church services. In one instance a lone perpetrator at Ende Cathedral was murdered on the spot (Aritonang and Steenbrink 257). During Easter on 25 April 1994 the offices of the court at Ende were burnt down by an angry crowd after a judge sentenced a man to just one year in prison after desecrating the host at a local Catholic communion (Bertrand 2004, 97). In May the six bishops of Flores, Timor and Sumba published a letter calling for public restraint while urging the government to enforce the law. However the situation was so inflamed that some prominent voices in Ende threatened to withdraw support from any priest who called for a non-violent response.

Religion remains a sensitive local issue and further violence erupted in Ende in 1999. On 28 March 2002, a young woman from Sumba Island attended church in Ende with a friend and accidentally dropped the host. She had to be evacuated out of a back window to avoid attack by angry churchgoers.

In 2003, heavy rainfall triggered flash floods, landslides and debris flows across Ende Regency. A large part of the village of Ndungga was destroyed by a flood and 27 villagers were killed. In Ende, both the airport and seaport were closed.

The current Regent or Bupati of Kabupaten Ende is Djafar H. Achmad, the ninth bupati to hold that position. He was elected on 8 September 2019 following the death of his predecessor, Marselinus Y. W. Petu in May. Prior to 2019 Djafar H. Achmad had been a Deputy Regent of Ende.

The Ninth Regent of Ende, Djafar H. Achmad

Return to Top

Bibliography

Aoki, Erico, 2003. “Centre” and “Periphery” in Southeast Indonesia, Globalization in Southeast Asia: Local, National, and Transnational Perspectives, pp. 145-164, Berghahn Books, New York Oxford.

Ardhana, I Ketut, 2005. Penataan Nusa Tenggara pada masa kolonial, 1915-1950, P. T. RajaGrafindo Persada, West Java.

Aritonang, Jan Sihar, and Steenbrink, Karl, 2008. A history of Christianity in Indonesia, Brill, Leiden.

Bertrand, Jacques, 2004. Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Indonesia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Cardon, René, and De Witt, Denis, 2016. The Fall of Portuguese Malacca to the Dutch, Nutmeg Publishing.

Dietrich, Stefan. 1989. Kolonialismus und Mission auf Flores (ca. 1900-1942), Klaus Renner Verlag, Hohenschäftlarn.

Farram, Steven Glen, 2004. From ‘Timor Koepang’ to ‘Timor NTT’: A Political History of West Timor, 1901-1967, Doctoral Thesis, Charles Darwin University, Darwin.

Farram, Steven Glen, 2010. The PKI in West Timor and Nusa Tenggara Timur 1965 and beyond, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 166, no. 4, pp. 381-403.

Forth, Gregory, 2006. Flores after floresiensis: Implications of local reaction to recent palaeoanthropological discoveries on an eastern Indonesian island, Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, vol. 162, issue 2-3, pp. 336-349.

Forth, Gregory, 2021. Between Ape and Human, Pegasus Books.

Galipaud, J., Kinaston, R., et al, 2016. The Pain Hakaburial ground on Flores, Antiquity, vol. 90, pp. 1505–1521.

Husson, L., Salles, T., Lebatard, A. E. et al, 2022. Javanese Homo erectus on the move in SE Asia circa 1.8 Ma. Scientific Reports, vol.12, 19012.

Jacobs, Hubert (ed.), 1974. Documenta Malucensia, vol. 1, (1542-1577), Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Rome.

Kate, H. F. C. ten, 1894. Verslag eener reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesië, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2nd ser. 11, pp. 659-700 and 765-823.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., 2015. Relasi Struktur Masyarakat dan Tata Zonasi Permukiman Adat di Desa Nggela, Ende-Flores, Atrium, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 75-92, Yogyakarta.

Lewis, E. Douglas, 2006. From Domains to Rajadom: Notes on the History of Territorial Categories and Institutions in the Rajadom of Sikka, Sharing the Earth, Dividing the Land, Thomas A. Reuter (ed.), pp. 179–210, Canberra.

Morwood, M. J., O’Sullivan, P. B., Aziz, F. and Raza, A., 1998. Fission-track ages of stone tools and fossils on the east Indonesian island of Flores, Nature, vol. 392, pp. 173–176.

Morwood, M. J; Aziz, F.; O’Sullivan, Paul B., and Raza, A., 1999. Archaeological and palaeontological research in central Flores, east Indonesia: Results of fieldwork 1997-98, Antiquity, vol. 73, pp. 273-286,

Morwood, M. J., 2001. Early hominid occupation of Flores, East Indonesia, and its wider significance, Faunal and Floral Migration and Evolution in SE Asia-Australasia, pp. 387-398, CRC Press.

Moorwood, M. J., and Jungers,W. L., 2009. Conclusions: implications of the Liang Bua excavations for hominin evolution and biogeography, Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 57, pp. 640–648.

Munizzi, Jordon, 2013. Changes in Neolithic Subsistence Patterns on Flores, Indonesia, Inferred by Stable Carbon, Nitrogen and Oxygen Isotope Analysis of Sus from Liang Bua, MA Thesis, University of Central Florida.

Needham, Rodney, 1983. Sumba and the Slave Trade, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash Univesity.

Petu, Piet P., 1966. Nusa Tenggara Setengah Abad Karya Misi SVD (1913-1963), Penerbitan Nusa Indah, Ende.

Ptak, Roderich, 1985. Die Portugiesen auf Solor und Timor: Europas Sandelholzposten in Südostasien im 16. and 17. Jahrhundert, Klemmerberg-Verlag.

Rodrigues, Francisco, 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires and the Book of Francisco Rodrigues. Translated from the Portuguese MS in the Bibliothèque de la Chambre des Députés, Paris, Cortesão Armando (ed.), The Hakluyt Society, London.

Roos, S., 1877. Iets over Endeh, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Landen Volkenkunde 24, pp. 481-580.

Rouffaer, G. R, 1923. Naschrift over het Oud-Portugeesche Fort op Poeloe Ende; en de Dominikaner Solor-Flores-Missie, Nederlandische-Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 1561-1638.

Sat-o, Tasuku, and Tennien, Mark A., 1957. I Remember Flores, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, New York.

Sprock, J. F., 1927. Memorie van Overgave, Ende.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002a. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1900, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002b. Another Race Between Islam and Christianity: The Case of Flores, Southeast Indonesia, 1900-1920, Studia Islamica, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 63-106, Jakarta.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2013. Dutch Colonial Containment of Islam in Manggarai, West-Flores, in Favour of Catholicism, 1907-1942, Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde, Vol. 169, no. 1, pp. 104-128.

Suchtelen, B. C. M. M. van, 1921. Endeh, Mededeelingen van het Bureau voor de Bestuurszaken der Buiten-bezetting, Bewerkt door het Encyclopaedisch Bureau (Afleverin XXVI), Weltevreden, N.V. Uitgev. -Mij. "Papyrus."

Suchtelen, B. C. M. M. van, 1922. De ruine van het out-Portugeesche fort op Poeloe Ende (Zuid-Flores), N.V. Boekdrukkerij Voorheen Firma T.C.B. Ten Hagen, Den Haag.

Suchtelen, B. C. M. M. van, 1923. De ruïne van het oud-Portugeesche fort op Poeloe Ende (Zuid-Flores), Nederlandische-Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 8, issue 3, pp. 79-95.

Sugishima, Takashi, 2006. Where Have the “Entrepreneurs” Gone? A Historical Comment on Adat in Central Flores, Asian and African Area Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 120-150.

Tanaka, Yuki, 2002. Japan’s Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and prostitution during World War II and the US occupation, Routledge, London and New York.Verhoeven, Theodor, 1958. Proto-Negrito in den Grotten auf Flores, Anthropos, vol. 53, pp. 229-32.

Vries, J. J. de, 1910. Residentie Timor en Onderhoorigheden, Onderafdeeling Endeh, Nota van Bestuursovergave.

Webb, Paul, 1986. “Too Many to Ignore….” Flores under the Japanese Occupation, Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 54-70.

Webb, Paul, 1986. The Sickle and the Cross: Christians and Communists in Bali, Flores, Sumba and Timor, 1965-67, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 94-112.

Weber, van-Bosse A., 1905. Ein Jahr an Bord I.M.S. Siboga: Beschreibung der holländischen Tiefsee-Expedition im Niederländisch-Indischen Archipel 1899-1900, Leipzig.

Publication

This webpage was published on 28 December 2021.