Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kampong Nggela 1

Local Geography

Oral History

Recent History

The Old Ancestral Village - The Oné Nua

The Village Zones

The Sa’o House Societies

The Sa’o Lima Rua

The Other Seven Sa’o

The Supporting Houses

The Traditional Sa’o Building

Lio Linguistics

Ethnography of the Ata Lio

Ata Nggela Kinship

Marriage and Bridewealth

Changing Bridewealth Composition

The Mosa Laki of Nggela

The Ceremonial Cycle

The Joka Ju Festival

The Loka Lolo Ritual

The Muré Ritual

Scholarship

Bibliography

Local Geography

The fascinating village of Nggela is located on the southern coast of the middle part of Flores Island in eastern Indonesia, 21km due east from Ende City. It is located within Kecamatan Wolojita, one of twenty-one districts that together form Kabupaten Ende or Ende Regency, one of nine regencies on Flores Island. They all belong to the Province of Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT), governed from Kupang.

The location of Nggela on Flores Island. Image courtesy of Google Maps

Nggela is only accessible by vehicle from the main trans-Flores highway to its north by a single-track road that passes south through Jopu and Pora. It can also be reached on foot from the adjacent coastal fishing hamlets of Ngalu Roga and Kapo Oné. Access along the coast from Ende is impossible because of the many intermediate steep ravines that slope down to the sea. Likewise access by sea is limited due to the strong swell and the rocky shoreline. The largest nearby settlements are Jopu and the small town of Wolowaru, just over 5km and 7km to the northwest respectively.

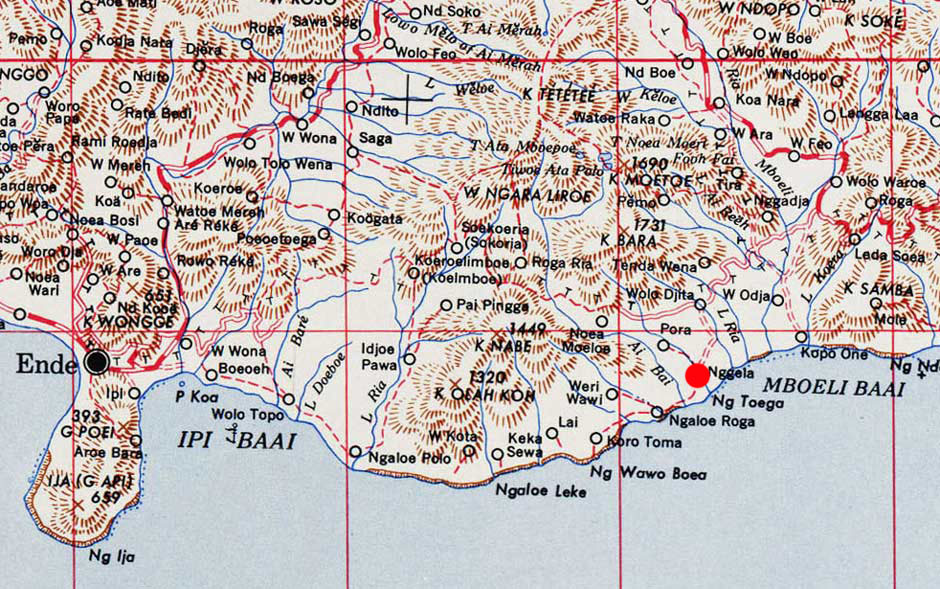

Topographically Nggela is located at the foot of Ende Regency’s southern mountain massif, dominated by the active volcano of Kéli Mutu (1613m), literally 'Boiling Mountain', and the dormant peaks of Kéli Bara (1731m), Kéli Nabe (1449m) and Kéli Olah Koe (1320m). This rugged region is bordered on its eastern side by the beautiful Mbuli Valley, carved out by the Mbuli River. Ende’s highest peak, Kéli Lépé Mbusu, dominates the northern mountain massif, which lies to the north of the trans-Flores highway.

Topographical map of the southern Lio coast (Courtesy of Google Maps)

Van Suchtelen noted that along the south coast of Flores in the region of Nggela, many steep ravines run down to the sea from Kéli Sukaria. Particularly striking is the broad ridge of Nggela, which slopes downwards towards the sea (1921, 24). Of the numerous nearby ravines, only the Ai Keo, just west of the Mbuli River, and Lowo Nggela, just to the east of kampong Nggela, bore water.

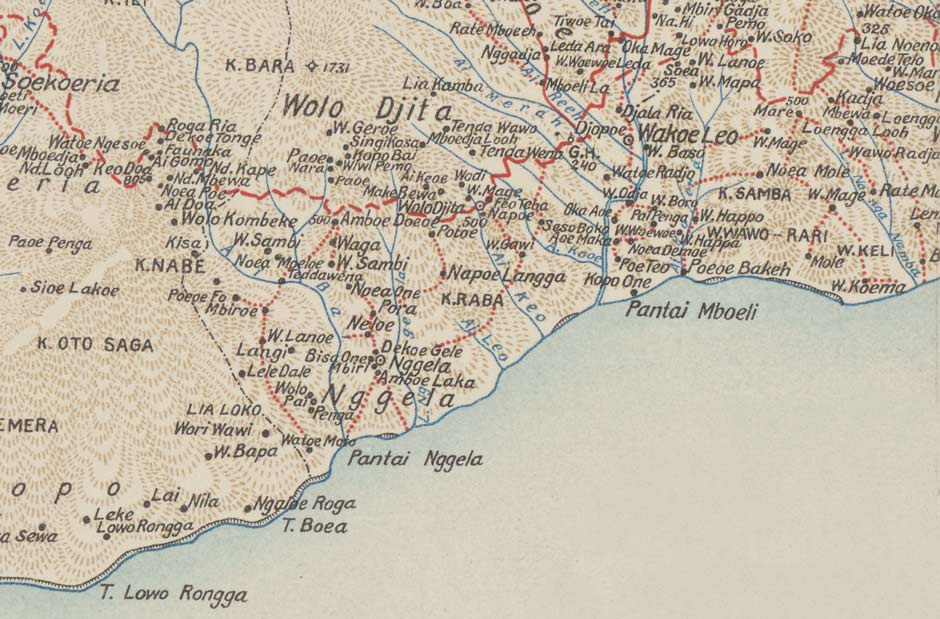

A map of Ende, Nggela and the southern Lio coast

(US Army Map Service, Washington D. C., 1943)

The settlement of Nggela was built in a special location – on a small plateau on the Nggela ridge, some 180m above sea level and located about 1km inland from the coast. It is one of the few small plateaus along this coastline. To the north the land rises up steadily to the peak of Kéli Bara but falls away steeply to the west and to the east down to the Lowo Nggela river. To the south it slopes down to the rocky coastline.

Looking down on Nggela from above Pora in 2017

Desa Nggela is one of six desa (village territories) within Kecamatan Wolojita and is divided into six hamlets or dusun, which all merge into one another. Dusun Oné Nua is the traditional heart of the desa containing the original ceremonial village. Its houses are mainly occupied by the village elders and their families. The modern part of the village lies to the west and south of this ceremonial centre. The entire settlement is surrounded by ladang, agricultural gardens that are cultivated using shifting slash and burn. Some of these are located close to the shore.

Above: The geography of kampong Nggela

Below: Dusun Oné Nua and the new village spreading out to its west

In 1990 the population of desa Nggela was 1,281 (551 males and 712 females) spread across 257 households. By 2008 the population had declined to 1,043 (442 males and 601 females) spread across 317 households (Lalo 2009). Of the 1,043 residents, 267 (25%) were below the age of 15. Of those aged 15 and above, there were 291 males and 485 females, a huge imbalance caused by the pressure on working men to find jobs in Ende City or further afield. Only 60 residents were aged 60 or over.

In 2021 the population of desa Nggela had fallen further to 1,010, composed of 476 males and 534 females (Kabupaten Ende).

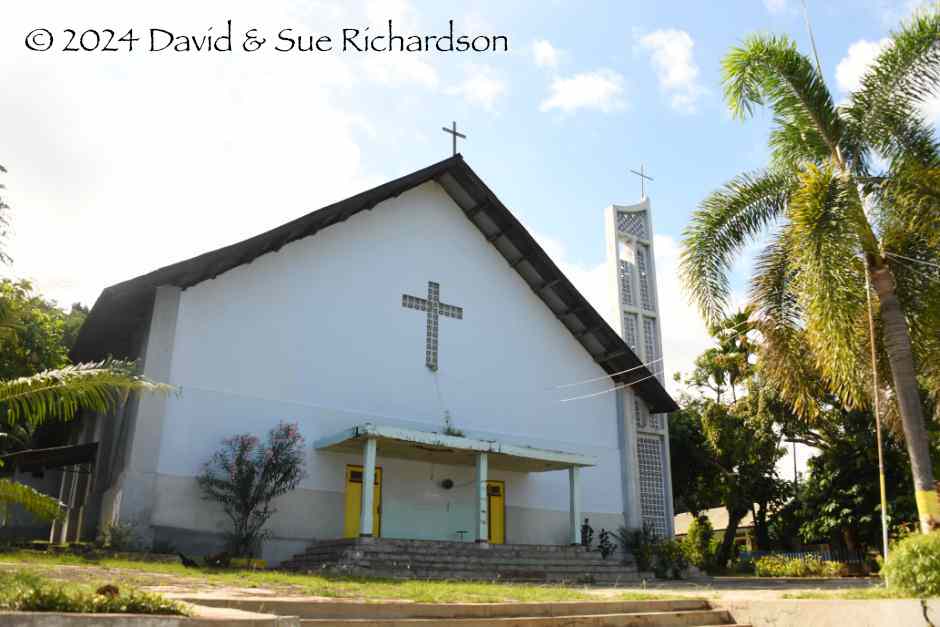

In terms of religion, in 2019 there were 966 Catholics, 108 Muslims and 1 Hindu. The church of Santo Theresia lies to the north of the village centre, indicating that it is a modern addition. There are also two small nearby mosques – Ar-Rahman in the fishing hamlet of Ma’u Alu and Jami At-Taqwa in Pora. Nggela has two elementary schools (SD) and one junior high school (SMP). Catholic nuns run the reliable clinic and hospital of Santo Antonius in Jopu.

The Catholic church of Santo Theresia

The local economy depends primarily on agriculture, the main crops being coconuts (201 hectares in 2008), coffee (116 ha), cashews (52 ha), chocolate (33 ha), areca nut (13 ha), candlenut (13 ha) and vanilla (1 ha) (Lalo 2009). The village also produces small amounts of clove, nutmeg and pepper. In 2009 some 3 hectares were planted with tree cotton.

According to a survey by Swisscontact, the main source of income from tourism was through sales of ikat. However local weavers obtain the largest share of their income by selling their textiles to local people (Remmer 2017).

The local water supply is obtained from the Ai Wando spring above the village. A second spring, commonly known as the Ai Nggela is located at a lower altitude than the traditional settlement.

Return to Top

Oral History

Oral genealogies suggest the Lio settled along the south coast in the late sixteenth century, and that Nggela was founded at the end of the seventeenth century.

Some central mountain Lio communities, such as those at Wologai at the southern foot of Kéle Lepembusu (studied by Yamaguchi 1989) and Kanganara to the northeast of Lepembusu (studied by Howell 1996) share a mythology that their ancestor, Ana Kalo, reached Flores Island in a small boat. He landed on the peak of Kéli Lepembusu, which at that time was surrounded by water, the sky linked to the mountain peak by a cosmic tree. Ana Kalo planted a garden but some of his sweet potatoes were stolen overnight. He therefore kept watch and discovered the culprit was a red pig, which he chased up the cosmic tree. In his frustration at the pig’s escape, he severed the trunk of the tree, allowing the heavens to ascend and the water to recede. Later he married a young girl and they had many children but they all perished because he could not cut their umbilical cord. In time he made a knife from the mast of his boat allowing him to cut the umbilical cord of two further children – a son and a daughter. The latter had many children and their offspring migrated down the mountain to populate the island and beyond (Yamaguchi 1989, 482-483; Howell 1996, 103).

The peak of Kéle Lepembusu in the central massif of Ende Regency

The communities of Tenda, at the eastern foot of Kéli Bara, and of Nggela believe that their ancestors came from Wewaria on the north coast of Flores, due north of Ende City, having previously arrived from the west (Prioharyono 2012). They then migrated south through Detusoko and Wolotukuku to the region of Kéli Bara, to the south of Kéli Mutu. The founding ancestor of desa Tenda was Déra, who had four sons. The senior mosa laki of Tenda claim to be the direct descendants of three of those sons.

The inferred migration route of the ancestors of Tenda and possibly Nggela

It is possible that this legend points to the arrival of Austronesian immigrants on the north coast of Flores from the southern islands of southwest Sulawesi and their subsequent gradual southern migration through the mountain passes that lead towards KéIi Mutu and then east and south to the region laying east of Kéli Bara.

According to Lambert Muda, the most senior mosa laki in Nggela, the village ancestors arrived from the north several centuries ago, perhaps around four hundred years ago (2018). There were many small groups migrating south from higher elevations, not because of conflict but because they were looking for better land. They are known as the ata nggoro – the people who came down. As they spread out through the southern foothills, they became separated into different communities.

One of the last of these groups decided to migrate further south. Some of them were the ancestors who founded the village of Nggela – A Nggoro and his wife Ni Mbuja. They had four children, three of whom were sons. The eldest was A Nogo, the next eldest was A Tori and the youngest was A Niri. Their youngest child was a girl called Ni Nggela.

This family decided to break away from their main community and head to the far south. They initially settled at Lelebewa just to the north of Nggela, and used the forest location of Nggela to distil tuak (Lontar palm wine). Later they moved to the present-day location of Nggela, on a raised plateau just 1km from the coast, naming their new settlement after their daughter.

The four siblings constructed four houses:

- A Nogo built Sa’o Rore Api

- A Tori built Sa’o Labo

- A Nira built Sa’o Wewa Mesa and

- Ni Nggela built Sa’o Ria.

Sometime later the families of A Rangga Se and A Tua arrived from Wewaria on the north Ende coast. A Rangga Se settled at the hamlet of Rangga Se, close to Jopu, but A Tua built Sa’o Tua in Nggela. They were followed by the families of Meko and Ndoka who built Sa’o Meko (next to Sa'o Rore Api) and Sa’o Ndoka.

Return to Top

Recent History

Although the Dutch installed a posthouder in Ende in 1855, he was merely a powerless observer with no political or military authority. The whole region remained under the control of local tribal chiefs, many of whom were engaged in warfare with neighbouring kampongs.

In 1879 the Resident of Timor split the administrative area or afdeeling of central and eastern Flores into five onderafdeeling – South Flores with its posthouder based at Ende, North Flores with a new posthouder installed at Maumere, East Flores with a civil gezaghebber at Larantuka, and finally Solor and Alor. The Mbuli Valley formed the border between North and South Flores, with Nggela falling just inside South Flores.

The five onderafdeeling of afdeeling Flores

Although the Dutch attacked some of the rebel mountain kampongs, even capturing some important Endenese and Lio leaders, the situation in onderafdeeling South Flores (by then known as onderafdeeling Ende) remained unstable. According to de Vries, prior to 1907 the Dutch had little influence beyond the city of Ende because in they were always constrained by the forces of the rebel Endenese leader Mari Longa.

A statue of the local hero Mari Longa at Wolowona, Kota Ende

As a first step in gaining a grip on central Flores, the new Resident of Timor, J. F. A. de Rooy despatched A. J. L. Couvreur to Ende in late 1906 as the new Controleur of Flores, tasked with assessing the situation on the ground. News of his arrival further inflamed the surrounding coastal and mountain villages, especially those to the west of Ende.

De Rooy responded with force. The experienced military leader Captain Hans Christofffel, a veteran of the war in Aceh, was sent from Kupang to Ende with a large force of marechaussee military police (the third korps of the fourth battalion). Arriving in Ende on 10 August 1907, his company departed for Nua Bosi on 12 August, a mountain village north of kampong Ende. Between 12 and 28 of August, he repeatedly patrolled the western region between Ndona and Nanga Panda. The company then left for what was then known as Rokka (Ngada), which had been in constant rebellion against the Dutch. They continued into Manggarai.

In 1909, Father Engbers, a Catholic priest from Sikka, together with the Raja of Sikka, Non Meak, embarked on a short missionary campaign to Nggela. At that time Nggela was regarded as becoming sympathetic to the Muslim faith. Engbers recorded 122 houses in the village and baptised just 9 children on his first day. The following day he held discussions with the local chiefs (mosa laki) and then baptised a further 31 children before returning to Sikka (Steenbrink 2007, 122).

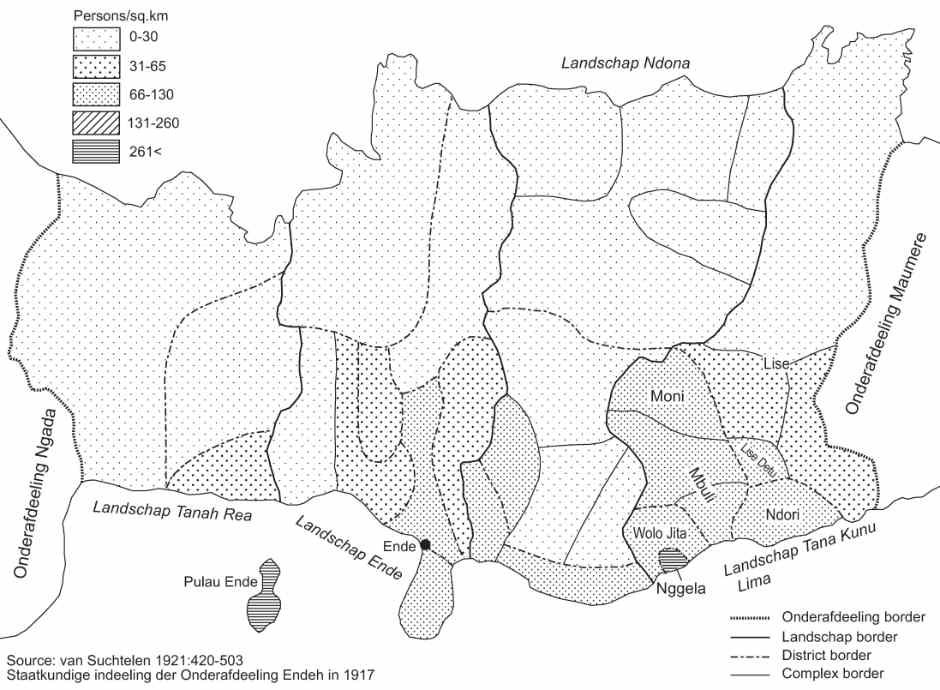

In April 1910 the 63 petty kingdoms of onderafdeeling Ende were reorganised into ten self-governing districts or zelfbesturende landschaps: Tanah Rea, Ende, Ndona, Wolojita, Nggela, Mbuli, Ndori, Lise, Poe and Sooi. Kaka Dupa was chosen as the Raja of Tanah Rea and Mbaki Mbani the Raja of Ndona. In the five landschappen of Nggela, Wolojita, Mbuli, Lise and Nduri the relevant mosa laki pu’u acted as landschapshoofd or district head (Dietrich 1989, 157).

A small Catholic school had been established in Ende in 1910 and a second soon followed at Mbuli. In 1911 van Suchtelen, who had just been installed at Ende as the gezabhebber of South Flores, put forward a list of 11 villages suitable for the establishment of schools. In 1912 he instructed Father Hoeberechts in Larantuka to send a Catholic teacher to Nggela (Steenbrink 2007, 101).

The Prefect of the Flores Mission based in Kupang visited Ende in 1914 and decided that the centre of the local SVD Catholic mission should be at Ndona, despite the fact that the village head was still a pagan. Ndona was chosen because it was in a non-Muslim area that was still close to Muslim Ende and was also next to a source of fresh water. Work began later that year and was soon extended to encompass a school with a dormitory for 60 pupils (Steenbrink 2007, 104). The mission was officially opened on 2 February 1916 (Steenbrink 2007, 105).

Further administrative consolidation took place in 1915, with the five disparate landshaps of Lisé, Mbuli, Nggela, Wolojita and Ndori combined to form the new landschap of Tanah Kunu Lima under Raja Pius Rasi Wangge, the son of the village head of Wololele in the eastern Lio region of Lisé. He had previously been a guide to the first Catholic missionary that visit this region from Sikka. Pius Rasi Wangge was chosen in favour of the more experienced and respected chief of Mbuli, Lenggo Gedo, because the latter was a Muslim whose son had already performed the Hajj. Pius Rasi Wangge was accepted by his five subordinate chiefs on the condition that they should be allowed to continue their traditional rights. They were each bestowed with the title of Kapitan (Steenbrink 2007, 107).

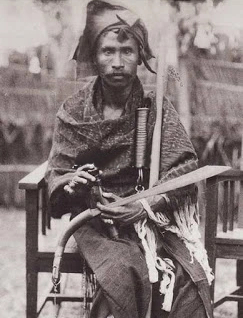

Raja Pius Rasi Wangge

Meanwhile the former landschaps of Ndona, Poe, Sooi, Moke Asa, Wolo Gai and Wena Ria were merged to form an enlarged landschap Ndona under Raja Mbaki Mbani. The latter turned out to be a firm supporter of the Dutch.

One of Raja Rasi Wangge’s tasks was to curb the influence of Islam in Tanah Kunu Lima. At some time after 1916 some help was provided by the SVD Catholic mission at Ndona, who opened a small mission post at Jopu.

In 1917 the four Rajas of Tanah Rea, Ende, Ndona and Tanah Kunu Lima were pressurised into signed formal agreements with the Dutch, known as the Korte Verklaring or ‘Short Declaration’ – a one-sided agreement designed by the Governor General of the Netherlands East Indies, Johannes van Heutsz, in which they recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies, including the payment of taxes.

Administrative structure of Onderafdeeling Ende in 1917

(From van Suchteren 1921, reproduced in Sugishima 2006, 127)

Detail of the Nggela region from an August 1918 ‘Sketch Map of Onderafdeeling Ende’,

produced by Charles Le Roux for the Controleur of Ende, B. C. C. M. M. van Suchtelen.

According to gezabhebber van Suchtelen, in 1918 the Raja of Ndona, Mbaki Mbani, embraced Islam, a serious setback given that Ndona was the headquarters of the Catholic Mission for the whole of the Lesser Sunda Islands.

The Dutch were keen to consolidate the native governments of the region so when the newly converted Muslim Raja Mbaki Mbani retired in 1920, landschap Ndona was merged with landschap Tanah Kunu Lima to create the enlarged Onderafdeeling Lio under the leadership of Raja Pius Rassi Wange (Steenbrink 2007, 107).

In March 1922 there was a new attempt to spread Islam in Nggela by a committed Muslim named Wawi. He bizarrely persuaded twenty-four schoolgirls to convert to Islam, promising them that this would free them from the obligation of attending school. Following Wawi’s advice, they travelled to Ende to stay in the house of Haji Ali. Raja Rasi Wangge intervened and returned the girls to their parents and to their Catholic school (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 242).

Raja Pius Rasi Wangge with Bishop Leven of Timor-Flores and his assistants

10 April 1924

Over the following decade Raja Rasi Wangge’s administration of Onderafdeeling Lio expanded significantly to the extent that he eventually had 50 subordinate Kapitans reporting to him. While Dutch officials in Ende found him efficient they also thought that he was corrupt and dishonest regarding his administration of taxes.

Despite being tasked with promoting Christianity and resisting the spread of Islam, a number of his subordinate Muslim Kapitans were allowed to take Catholic girls as second or third wives while some local chiefs, especially in Nggela and Mbuli, were allowed to convert to Islam.

By the late 1930s the Dutch colonial government in Kupang became repeatedly annoyed by local conflicts in Onderafdeeling Lio and by the behaviour of Raja Pius Rasi Wangge, who by then had a reputation for theft and had also been accused of several murders. In 1940, he was ordered to Kupang by the Resident of Timor, Fokko Jan Nieboer, and put on trial. He was finally deposed in 1941 and sentenced to ten years exile in Kupang (Steenbrink 2003, 109; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 243). A large number of his Kapitan were punished in a similar manner.

Pius Rasi Wangge from Wololele in the eastern Lio region of Lisé

Despite this long sentence, when the Japanese occupied Flores in 1942 they released Pius Rasi Wangge from exile in Kupang and returned him to Flores as an adviser to the local Japanese administration. A European priest claimed that this made it possible for him to resume his old ways of extorting the local population (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 243). After the war he was taken back to Kupang by the Dutch and tried as a collaborator. He was executed in April 1947. According to Raymond Kennedy, one of Pius Rasi Wangge’s crimes was the killing of young girls for agricultural field rites (1952, 268).

De Jong suggests that it was probably around 1947 or following independence in December 1949 that the keda village temple in Nggela was rebuilt for the final time, a major project involving the whole village and culminating in a complex ceremony led by the senior mosa laki (De Jong 2007, 221).

In 1957 the Province of Nusa Tenggara was spilt into three, with Flores belonging to the new Province of Nusa Tenggara Timur. In December of the following year, NTT was divided into twelve regencies, one of which was Ende, the latter composed of six kecamatan or sub-districts, Nggela being part of kecamatan Wolowaru.

Following the attempted coup of 1 October 1965, General Suharto claimed that it was organised by the Indonesian Communist Party, the PKI, and some months later initiated a bloody nationwide campaign to purge communists throughout the archipelago. At the start of 1966 the army began a witch-hunt across NTT and suspected PKI sympathisers were rounded up and either executed or beaten, some publicly in order to terrorise the local population. PKI sympathisers included low level government workers, teachers, some members of the clergy, rural farmers and Muslims.

To promote their anti-communist drive, the Suharto regime exploited religion, emphasising the Pancasila principle of ‘Belief in One Almighty God’. Henceforth all Indonesian citizens were obliged to belong to one of the six officially recognised religions, the name of which had to be stated in their Kartu Tanda Penduduk resident identity card. Those who had no religion were forced to claim one or risk prosecution as communist sympathisers. In central and eastern Flores this led to a mass conversion to Catholicism. According to villagers in Nggela, many non-Christian residents rapidly became Catholics.

Even so, the Catholic church of Santo Theresia was not constructed until 1978. The influence of the church soon began to influence the villager’s traditional beliefs. The full yearly cycle of agricultural rituals was performed for the last time in Nggela in 1980.

In 1990 Nggela had 257 households and a population of 1,283, over 25% larger than it is today. Just like today there was an imbalance of genders, there being only 551 men as opposed to 712 women.

On 12 December 1992 at 1335 central and eastern Flores were rocked by a tectonic earthquake of 7.8 on the Richter scale, located in the Flores Sea. This created a massive tsunami that inundated the north coast, causing widespread damage to both urban and rural buildings inland. Many buildings in Nggela were affected.

By now most of Nggela’s traditional houses were suffering from neglect and many were being progressively abandoned as the village’s traditional cultural practices were being neglected. Fortunately, around 2012 Lambertus Muda succeeded his father as the head mosa laki and began encouraging the villagers to renovate the traditional houses and reinvigorate the annual cycle of cultural rituals and celebrations.

Six years later the village suffered a major calamity. On at 2am on the morning of 29 October 2018 the important Sa’o Labo traditional house in the ancestral Oné Nua caught fire as result of an electrical fault. Fanned by strong winds the fire spread rapidly throughout the village. Twenty-two traditional sa’o nggua named houses, ten ordinary houses and a meeting hall were completely destroyed. In addition, many important cultural artefacts were lost, including traditional textiles and jewellery. Mosa laki Gabriel Manek later estimated the cost of the damage to be around Rp. 5 billion (about $350,000), a huge sum for such a small community.

The devastating 2018 village fire spreading from sa’o to sa’o

Nggela had been affected by fire on four previous occasions, the last being in 1969. However, the previous fires only consumed one or two houses and were quickly extinguished.

After the debris was cleared, some small temporary houses were constructed to accommodate the previous occupants of the traditional sa’o.

Above: The Oné Nua after the fire in May 2019

Below: Nggela in late 2019 showing the temporary housing

A group of volunteers, including Willemijn de Jong, formed Nggela Kami Latu (Nggela We Exist), a project aimed at raising funds towards the rebuilding of twenty-two traditional houses. The group held charity auctions and fundraising events in Jakarta, Surabaya and Ende. Donations were received from across the archipelago and also from overseas, from academics, professionals, NGOs, civil servants and others.

By December 2019 sufficient funds had been raised to begin the construction of thirteen houses. Eight had been financed by the Directorate General of Culture of the Ministry of Education and Culture, two by the Government of Kecamatan Ende, one from the Provincial Government of NTT, and two by the Tirto Foundation. By October 2021, eighteen had been completed while three were under construction and funds were being raised to build the twenty-second. The work was undertaken by local craftsmen using traditional construction techniques and local materials.

Constructing the new sa'o nggua

Above and below: The newly rebuilt traditional village in 2022

(Drone images courtesy of Freddy Hambuwali)

Return to Top

The Old Ancestral Village – The Oné Nua

In 1921 van Suchtelen noted that in the past Lio settlements were built in locations that were easier to defend – on high peaks or ridges or next to obstacles or terrain that was difficult to overcome (1921, 57). In villages in the southern Lio region the number of houses was generally not great. In the most ‘primitive regions’ there were only six to twenty houses, although in the more developed regions such as Nggela, Mbuli and Nduri there were sometimes considerably more. In the majority of villages there was often little regularity to be recognized in the placement of houses. At that time Nggela was the largest kampong and had about 60 houses. In this region the kampongs were often built on relatively large plains.

The Lio frequently define spaces based on the anatomy of a snake, with a head (ulu), tail (eko) and navel (pusu or pusé) (Yamaguchi 1989, 480). Thus, Flores Island has its head in the east, its tail in the west and its navel located at the sacred mountain of Lepembusu. Villages were described in the same manner.

It has been claimed that Lio villages are oriented with their head (ulu) facing Kéli Lepembusu or the rising sun and their tail (eko) facing downhill or the sunset, Lepembusu being considered the Lio point of creation (Kerong 2015; Paru 2018). This is only approximately true for the ancestral heart of modern Desa Nggela, which is known as the oné nua (oné meaning central but also referring to a house and nua meaning the ritual domain). The latter is oriented towards the northwest, not towards Kéli Lepembusu, which lays almost due north.

A view of Nggela looking north towards Kéli Bara pre-2018

The Lio refer to their ancestral villages as nua pu’u. In the Lio language, the nua being the ritual territory, domain or polity and pu’u being the trunk or source or origin of the domain (Aoki 2006, 318). However, the people of Nggela refer to their nua pu’u as the oné nua. This was laid out with two curved rows of thatched wooden houses facing each other across an open earthen arena, creating a shield-like shape rather than an oval. Of the total thirty-seven traditional houses, fourteen are named houses or sa’o nggua while seven are supporting houses or poa paso (poa = early, paso = pass). In addition there are sixteen ordinary living houses, known in Nggela as oné. The Lio term for betrothal is nai oné, which literally means ‘to enter the house [of the future wife]’.

The central open space contains a number of sacred and ritual features (Kerong 2016, 160):

- the kanga ria is the stone platform where traditional ceremonies are held. It incorporates the stone graves of the most senior clan leaders, known as the mosa laki. The leader of the mosa laki being the highest grave and the executive mosa laki the lowest.

- The tubu musu oval stone is placed close to the kanga and is used to make sacrifices to the ancestors and to God. In many Lio villages there is normally a flat stone, the lodondà, and a standing stone, the tubu.

- The pusé nua is the navel or heart of the settlement and is marked by an oval of flat stones.

- There is also the rate lambo, a grave in the shape of a boat, built for the architect Wulu Koli who designed and constructed some of the traditional houses.

These features along with the traditional houses are enclosed by a stonewall called the kopo kasa. It is entered at the north through the ceremonial gate of the village known as the kai peri lesu usu.

Above and below: the flat-topped kanga

The pusé nua, the sacred village centre

In the past there was a village temple or kéda, originally built in about 1933 and renovated in 1947, just before independence. Over time it became derelict and was not rebuilt. Its reconstruction would have been an expensive project requiring the cooperation of all the sa’o. Given the rivalries and jealousies between the village elders, this was never likely to happen, especially since the 2018 fire when all of the available resources have been invested in rebuilding the clan houses.

Return to Top

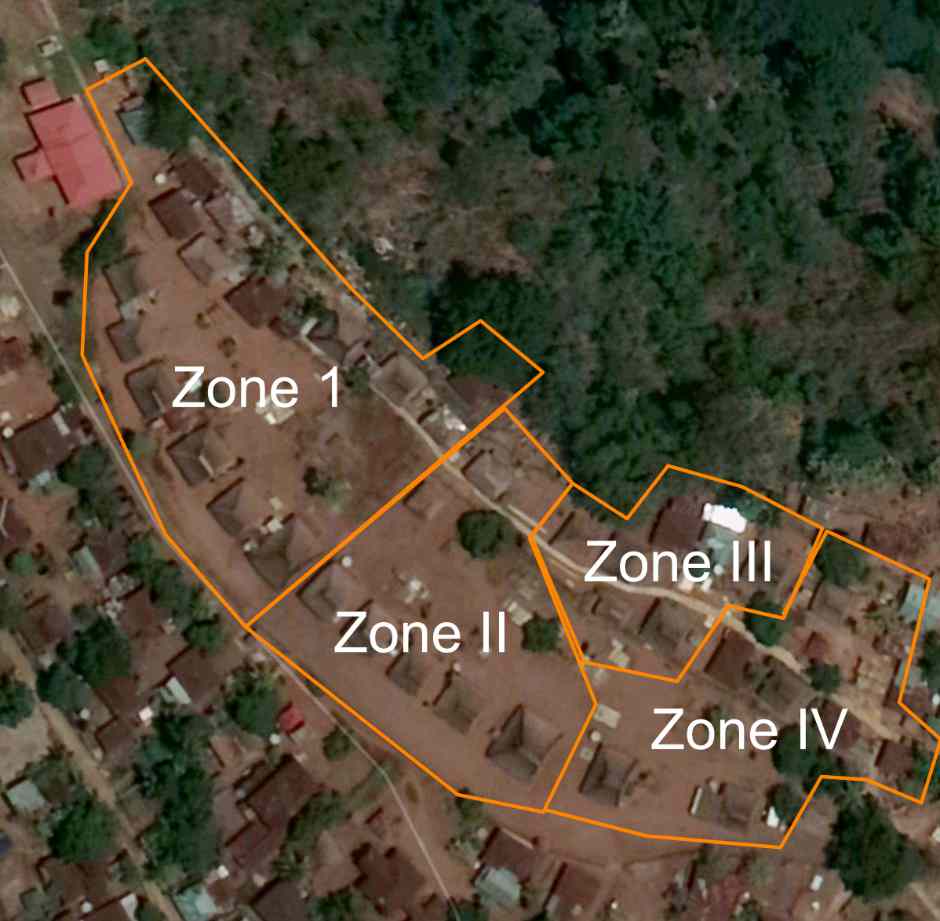

The Village Zones

The oné nua ancestral village is divided into four zones, starting from the first area to be settled by the original ancestors.

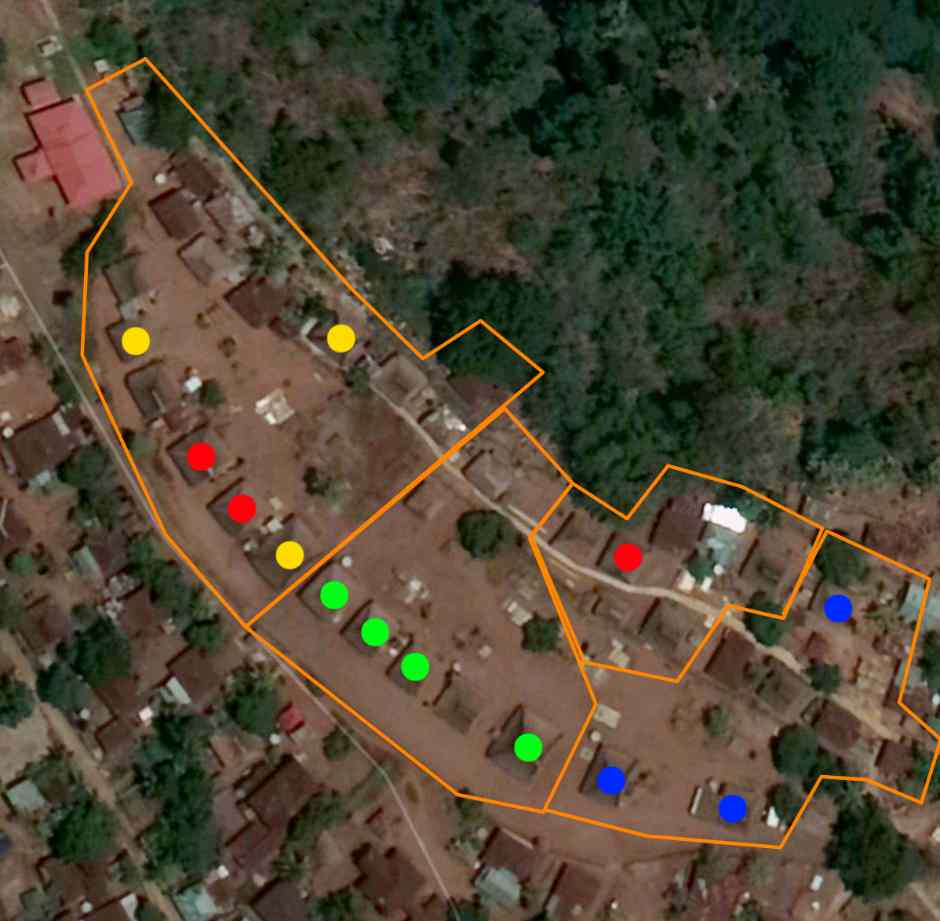

Above: the village zones. Below: the first houses settled are coded red, the second yellow, the third green and the fourth blue.

The northernmost zone I is the Bhisu Dheko Gele, the term bhisu meaning part of an area or a zone and dheko meaning edge, as in edge of the village. This is the highest status area of the village because it is believed to be the earliest part established by the ancestors. It is the location of four sa’o nggua named houses. The first, Sa’o Labo, was founded by Tori, the second eldest male sibling who was the first ancestor to inhabit the original kampong. The others are Sa’o Meko, Sa’o Tua and Sa’o Ame Ndoka. Zone I also contains four poa paso (supporting houses) – Sa’o Kai Pere Lasu Usu, Sa’o Siga, Sa’o Rore Api, and Sa’o Terobo – as well as six residential houses.

In addition, Zone I also contains the kanga ria, the traditional court which is also the site of the mosa laki traditional ceremonies as well as incorporating the graves of ancestors of the mosa laki iné ame and mosa laki pu'u. The kanga ria was originally in the centre of the early village, but as it expanded southwards it is now in the northern part. Zone I also encompasses the oval tubu musu stone, used for donating offerings to the ancestors, and the pusé nua, the centre or heart of the settlement equivalent to the belly button.

The western zone, numbered II, is the Bhisu Oné, the term bhisu meaning part of an area or a zone and oné meaning centre. Zone II contains three sa’o nggua named houses – Sa’o Ria, Sa’o Pemo Roja and Sa’o Ndoja – along with one poa paso and one residential house. It is also the location of the pusé nua, the flat stones that mark the heart of the indigenous settlement, and the rate lambo boat-shaped grave.

The left or east zone, numbered III, is the Bhisu Mbiri, apparently named after a former resident called Mbiri. This is zone occupied by Sa’o Wewa Mesa, the only sa’o nggua house that does not face the central arena but is oriented towards the south because its function is to monitor access to the village from the sea. This zone also contains Sa’o Leke Bewa, Sa’o Samba Jati and Sa’o Watu Gana along with seven residential houses. It also contains a sacred stone positioned in front of Sa’o Watu Gana.

The south zone, numbered IV, is the Bhisu Embu Laka, the southernmost part of the settlement. This is the area where the fourth influx of settlers established their residence, some believed to have been Portuguese immigrants from Malacca. It contains Sa’o Embu Laka, Sa’o Bewa and Sa’o Tana Tombu along with one poa paso and three residential houses. There is also a sacred wooden relic claimed to have been installed by a Portuguese missionary.

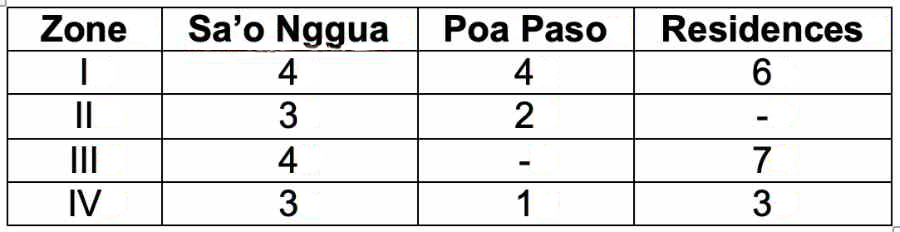

The number of houses in each zone

Return to Top

The Sa’o House Societies

The people of Nggela are grouped into house societies where kinship and political relations are organised around membership of corporately-organized dwellings rather than around descent groups or lineages. This is an alternative social order to those based on kinship or social hierarchy.

The concept of the house society was initially proposed by Claude Lévi-Strauss in 1976. He defined a house as a corporate body holding an estate made up of both material and immaterial wealth, which perpetuated itself through the transmission of its name, its goods and its titles down a real or imaginary line considered legitimate as long as this continuity could express itself in the language of kinship or of affinity and, most often, of both.

Lévi-Strauss later attempted to define the term more specifically (Lévi-Strauss 1991, 435). A sociétés à maison (house society) is:

1. a corporation

2. the holder of a domain

3. composed of both material and immaterial goods, and which

4. is perpetuated by the transmission of its name, its fortune and its titles in line real or fictitious,

5. held to be legitimate on the condition that this continuity can be translated into the language of kinship or alliance, or

6. most often both together.

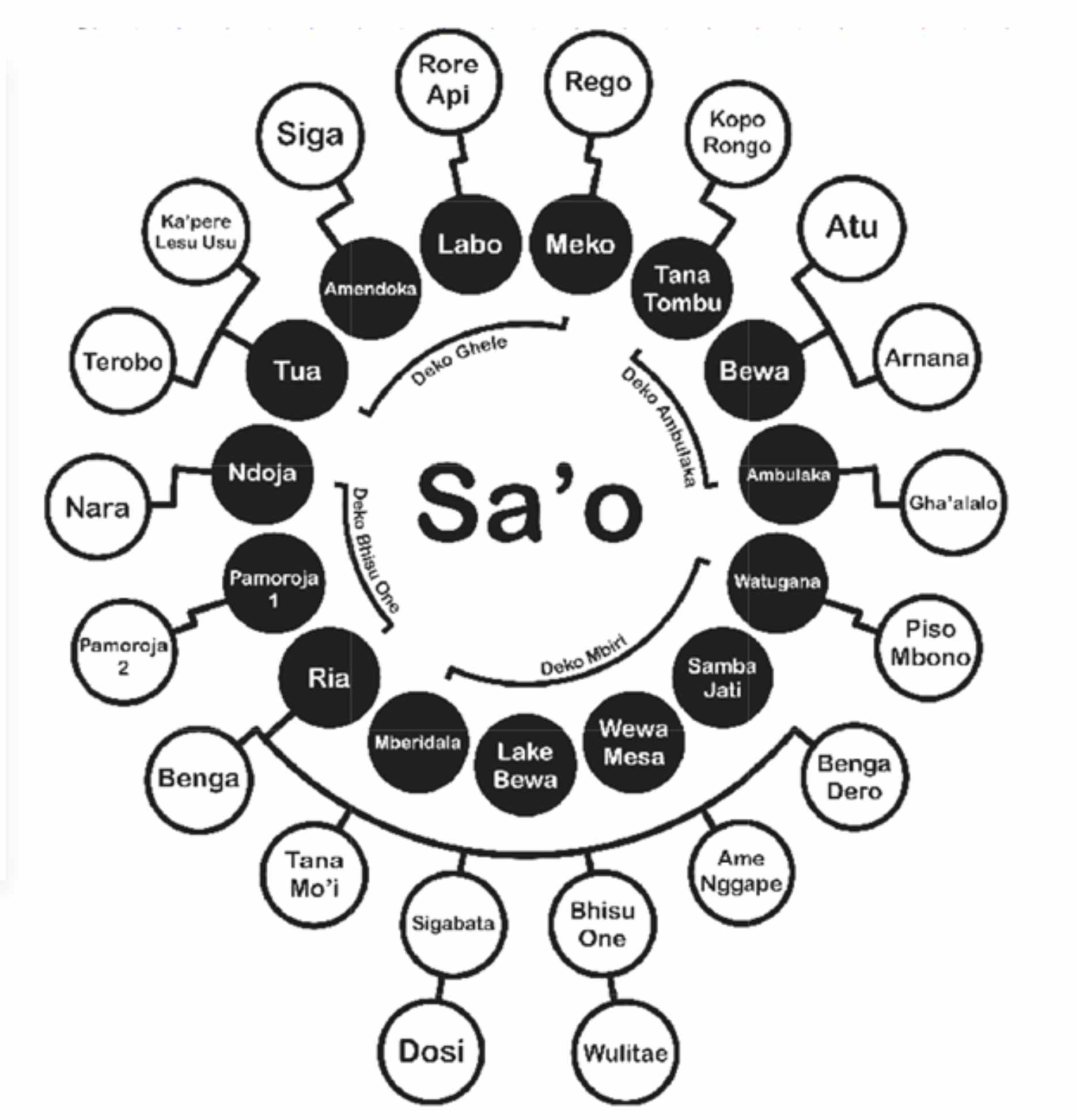

Nggela has twenty-eight sa’o house societies, fourteen of which are named houses called sa’o nggua (houses of the agricultural festivals, a nggua being an agricultural festival), each headed by a titled nobleman called a mosa laki. Seven of these sa’o nggua – the sa’o lima rua – claim precedence because their ancestors were the first to settle.

Return to Top

The Sa’o Lima Rua

The highest status clan houses are the ‘seven houses’ or the sa’o lima rua (‘houses five two’). These accommodate the nine most senior mosa laki, who must be present at every traditional village ceremony, both major and minor. The founders of these seven sa’o came to the village first. The two most important patrilineages are Sa’o Labo and Sa’o Ria. The third is Sa’o Leke Bewa. These are the homes of the five most senior mosa laki, there being three mosa laki based in Sa’o Ria.

Above: the locations of Sa’o Labo and Sa’o Ria

Below: the locations of ten of the named sa’o nggua

Sa'o Labo was founded by Tori, the second eldest male sibling who was the first ancestor to inhabit the original kampong. Sa'o Labo is therefore the home of the mosa laki pu’u iné ame, who supervises all the other mosa laki. Pu’u is the trunk or origin, while iné ame is father mother, so this mosa laki is a descendant of the first ancestor. The old house had a buffalo skull as a doorstep and breasts carved from jackfruit wood on the inside remind you of the mother and the tribe’s origin. This house serves as a place of consultation if there is a problem throughout the Nggela customary law area. The present mosa laki pu’u iné ame is Lambertus Muda. Sadly Lambertus lost his wife Veronika in 2020. Her grave lies in front of Sa’o Labo.

Lambertus Muda, the mosa laki pu’u iné ame, in 2023

Sa’o Labo in 2023

Sa'o Ria was founded by the youngest sibling Nggela. It previously housed the large elephant tusks. It is the home of the executive mosa laki pu'u (the origin priest the pu’u being the trunk or origin), Pak Gabriel Manek. He is effectively the leading mosa laki, his powers being delegated by the mosa laki pu’u iné ame. He is also responsible for the inauguration of the other mosa laki and for making offerings to the ancestors. He shares Sa’o Ria with two other mosa laki: the mosa laki turu tena nata ae, Thomas Nggomba, who assists with the planning and initiation of ceremonies and is in charge of receiving guests, and the mosa laki ru’u tu’u jaga tau rara, Ambrosius Gengu, who is the prosecutor responsible for sanctioning individuals who are in breach of customary law.

Above: Sa’o Ria with the elephant tusks. Below: the three mosa laki Thomas Nggomba, Gabriel Manek and Ambrosius Gengu standing in front of rebuilt Sa’o Ria in 2023.

Sa’o Leke Bewa is the home of Vinsensius, the judge mosa laki ria béwa (the great priest, ria being big or great and béwa being long, high or deep). This mosa laki is responsible for resolving problems involving the violation of customary law. His role is to interrogate the suspect, but the final judgement is the responsibility of Sa’o Ria.

Sa’o Meko is the home of the mosa laki tau kowe uwi, Laka Doane Marianus, who serves as the guard and keeper of the kanga, the location of the traditional ceremonies. He is also the head of kampong Nggela. Sa’o Meko is located right beside Sa’o Rore Api.

Sa’o Tua is the home of the mosa laki dai ulu nua, Pelipus Buga, who is responsible guarding the entrance to the traditional settlement and for accepting guests who enter it from the north and escorting them to Sa'o Ria.

Sa’o Pemo Roja is the home of the mosa laki tau piara nggo lamba, Raimundus Redu, who is in charge of maintaining and caring for the gongs, drums and other musical instruments used in the traditional ceremonies.

Sa’o Ndoja is the home of the mosa laki tau tunu, Aloysius Poto, who is responsible for sacrifices and maintaining and supervising the keda, a hypothetical role since the previous keda has not been rebuilt.

Return to Top

The Other Seven Sa’o

Sa’o Ame Ndoka is headed by the mosa laki ndeto au, Aurelius Mbulu, who is responsible for deciding whether or not the fine (usually in the form of a pig) given to a person who committed an adat violation is appropriate. The ancestor of this >mosa laki arrived in Nggela with the ancestors of Sa'o Meko.

Sa’o Bewa is headed by the mosa laki ndeto au, Aloysius Sika, who is responsible for determining whether or not the fine given to the person who committed the violation is appropriate.

Sa’o Embu Laka is headed by the mosa laki ndeto au, Selvisius Nabi, who is responsible for guarding the southern part of the settlement and accepting guests who arrive by sea. He is also responsible for setting the fines given to people who commit violations of customary law.

Sa’o Wewa Mesa is headed by the mosa laki tau dai ulu ae, Damianus Jenasem, who is responsible for guarding Nggela in case there is an attack from the sea to the south. This is the only sa’o nggua house that does not face the central arena but is oriented towards the south, the reason why it is not located in the northern Bhisu Dheko Gele zone. It was founded by Nira, the youngest male sibling.

Sa’o Samba Jati is headed by the mosa laki gao lo kaka taga, Paulinus Tali, who is tasked with helping other mosa lakis in performing traditional ceremonies.

Sa’o Watu Gana is headed by the mosa laki bei nggo, Eduardus Mberu, who is responsible for playing a musical instrument at certain times. He also helps the other mosa laki in carrying out traditional ceremonies. This sa’o hasa sacred stone positioned in front that cannot be touched.

Sa’o Tana Tombu is headed by mosa laki tau sani, Melkiades Paru, who is responsible for helping the other mosa laki in carrying out traditional ceremonies.

Return to Top

The Supporting Houses

The poa paso ‘supporting houses’ support and assist the mosa laki in carrying out their duties. Most but not all of the sa’o nggua have supporting houses. In particular, Sa’o Ria, the wealthiest sa’o has eight poa paso.

The relationship between sa’o and poa paso

Courtesy of Badriantoro 2020

The five poa paso traditional houses in Bhisu Deko Ghele are Sa’o Kai Pere Lasu Usu, Sa’o Rego, Sa’o Rore Api, Sa’o Siga and Sa’o Terobo. In addition there are six residential houses.

Sa’o Rore Api was founded by Nogo, the eldest sibling. Sa’o Rore Api serves as a provider of fire, which is used to cook food for ceremonial rituals such as the Jaka Uwi event. The fire provided is not produced with matches, but is created by the friction of rubbing two bamboo blades together. Only people who are descendants of A Nogo are allowed to swipe the two bamboo blades.

Return to Top

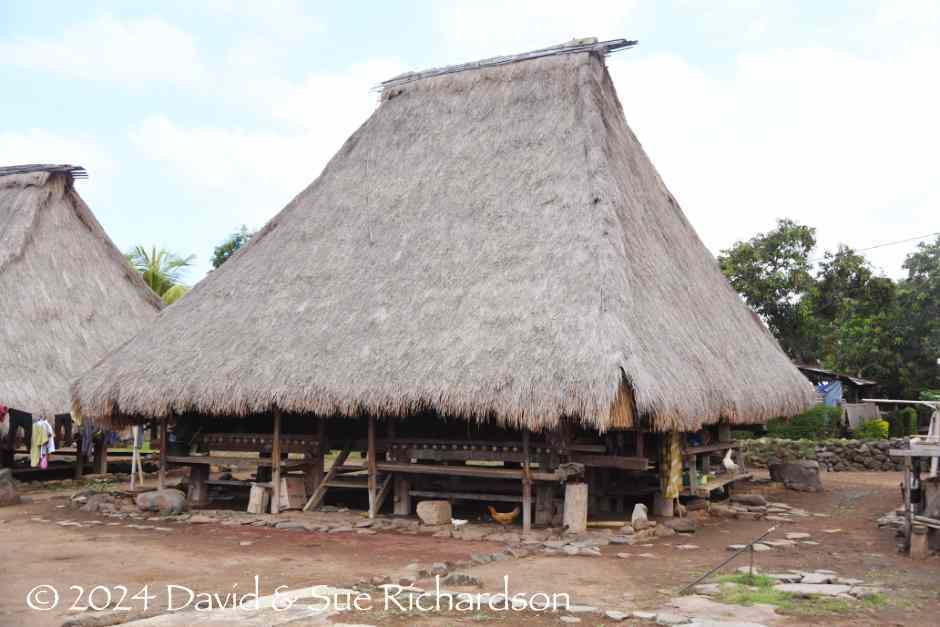

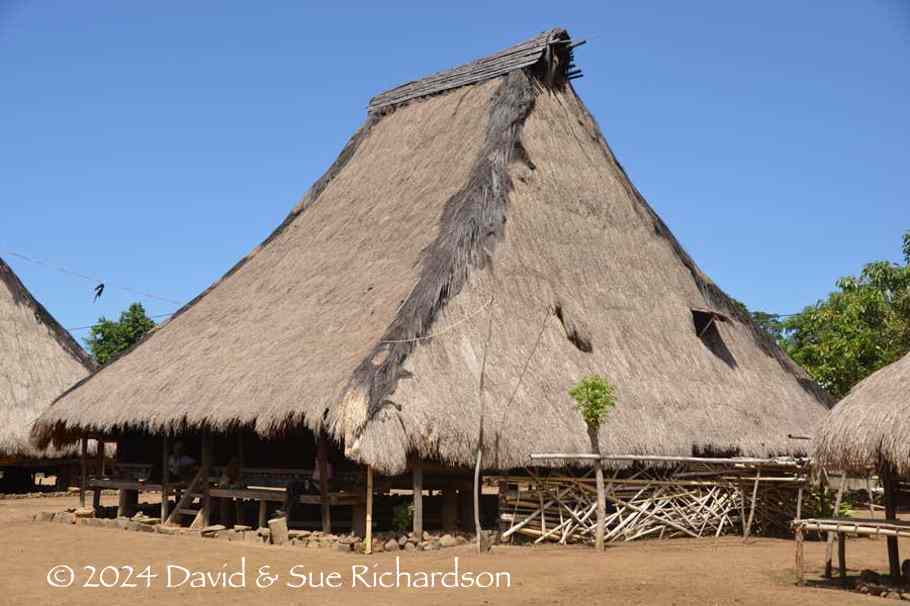

The Traditional Sa’o Building

The sa’o nggua named houses are constructed from local hardwood, bamboo and coconut wood, with the roof covered in alang-alang grass. They need to be reroofed every 10 years.

The architectural structure of the house is founded around four upright wooden corner pillars that rest on flat stones. These are linked by cross-beams fastened with wooden pegs, one set at floor level and another set at ceiling level, the latter supporting the roof struts. The top of the roof struts are fixed to a lateral ridge beam that is supported by two inner pillars that are connected and stabilised by a pair of angled cross beams.

The timber frame structure of a sa’o nggua

(Image courtesy of Sado, Wulandari and Wahjutami 2021)

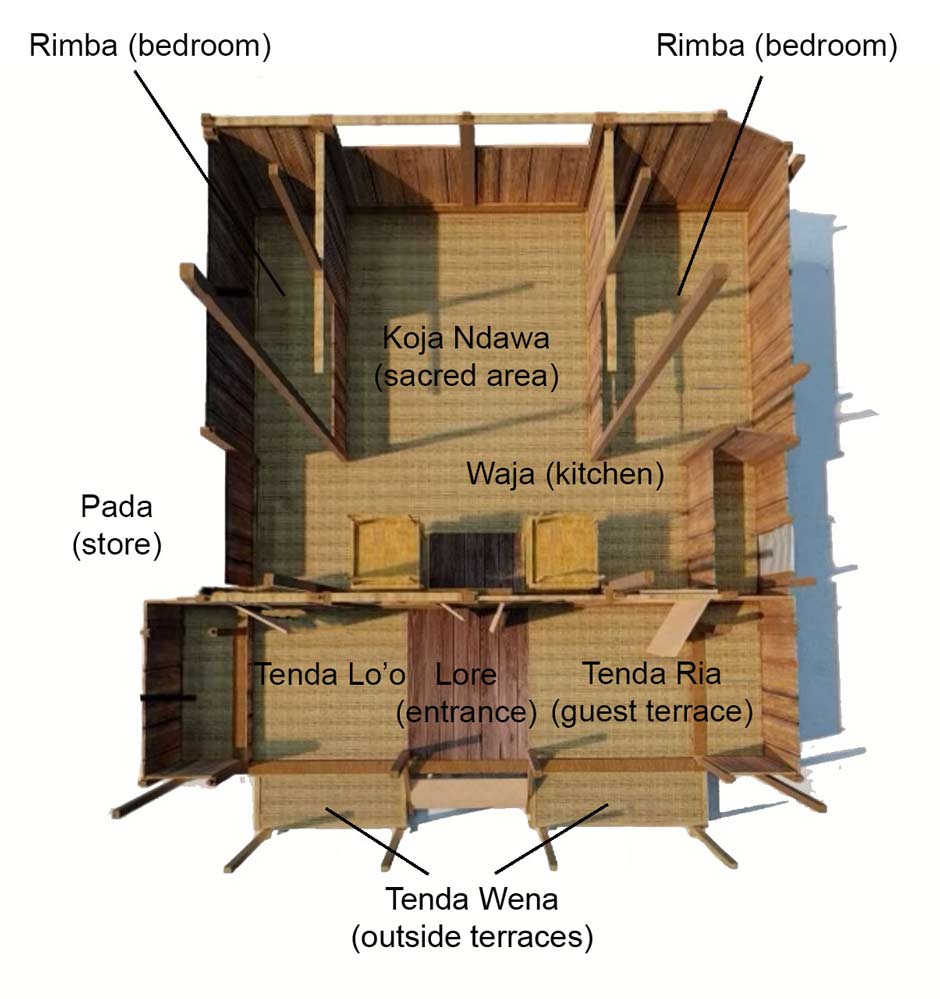

The floors and terraces (tenda) are made of bamboo slats arranged parallel in one direction, allowing air to flow through the building. The walls are also made from bamboo slats.

The heart of the sa'o is the middle room or koja ndawa, which functions not only as a family meeting area but also as a sacred place for the gathering and deliberation of the mosa laki.

The plan of a traditional sa’o nggua

After Saudale 2021

The interior of newly-built Sa’o Lobo showing the kitchen and sleeping quarters

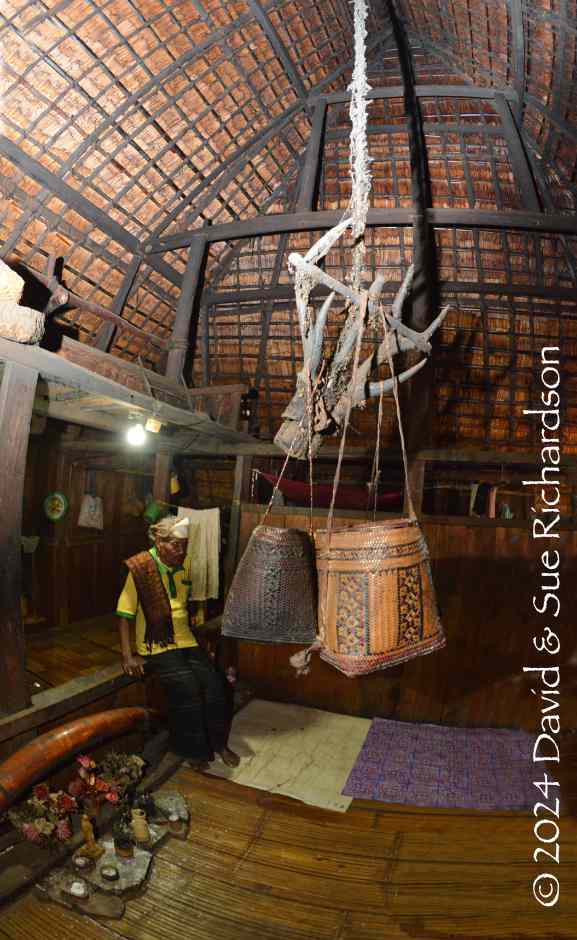

A rope known as the olé teo descends from the peak of the roof and holds the antlers of a deer from which hang three woven pandanus leaf baskets. It is the symbolic umbilical cord of the house. Only the mosa laki are allowed to touch it. One basket contains the paribara, the sacred ceremonial glutinous rice.

Above: the sacred centre of Sa’o Ria in 2017 with a pair of elephant tusks, a large one from a male and a small one from a female, plus a small Catholic altar. Below: the olé teo suspended from the highest point of the room

Any guest who enters the house must pause at the entrance and allow one of the mosa laki to press a small lump of the sacred rice onto their forehead, a ritual whose purpose is to appease the ancestors.

Mosa laki Thomas Nggomba presses rice onto David’s forehead on the threshold of Sa’o Ria in 2017

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 8 February 2024.