Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Weaving in Ende Regency

Historical References to Endenese and Lio Textiles

Samuel Roos 1877

Herman ten Kate 1891

Max Weber 1899-1900

Johannes Elbert 1912

Charles Le Roux 1915-1919

Bertho van Suchtelen 1921

Elisabeth Wilhelmina Viruly Verbrugge 1922

Father Simon Buis SVD 1923

Raymond Kennedy 1949-1950

Roy Hamilton 1989

Willemijn de Jong 1987-2022

Conclusions

The Nggela Weaving Community

Nggela Ecology

Local Cotton and its Preparation

Commercial Cotton and Synthetic Yarns

Warping Up and Binding

Indigo Dyeing

Morinda Dyeing

Other Natural Dyes

Synthetic Dyes

Unbinding and Starching

Assembling and Focussing

Final Starching

Weaving in Nggela

Loom Terminology

Sewing Up the Sarong

The Complete Weaving Process

Women’s Sarongs

Lawo with Centre Panels

Lawo with Vertical Bands

Lawo with Horizontal Bands

Lawo Butu

Men's Textiles

Luka Sarongs

Luka Shoulder Cloths

Bibliography

Weaving in Ende Regency

The majority of the Ende Regency region is devoid of weaving. Weaving amongst the Ende-Lio community tends to be confined to villages located on, or near, the rugged south coast. This is not only where the local ecology is conducive to the growth of cotton, indigo and morinda, but also where agricultural conditions are harsh and income from the sale of cloth is vital to village economies.

As in other parts of eastern Indonesia, the local ecology has stamped its impression on the people’s beliefs and customary law. In the inland Lio mountain villages where indigo and morinda does not grow and it would be almost impossible to cultivate cotton, it is not that women do not weave – they are forbidden to weave.

In 1929 P. Cornelissen SVD, the director of the Catholic seminary in Maumere, reported that in the Lio region of Lise, in the far eastern region of Ende, girls were not allowed to weave, so were forced to buy their clothes elsewhere. This prohibition only applied to a few kampongs, including Wolosoko. Yet in nearby Lisedetu, just north of Wolowaru, the women made beautiful fabrics.

More generally, as Father Piet Petu SVD noted in 1992:

Weaving is not found in the inland region or in the north (Sareng Orinbao 1992, 53).

In 1994 Roy Hamilton added:

There is no weaving at all in Maurole and Detusoko Districts. The same ecological constraints are at work here as in other parts of Flores. Many of the strongest weaving communities face extremely harsh agricultural conditions, income from textile sales is vital to household budgets (Hamilton 1994, 124).

He later continued:

Of the five constituent communities [of Tana Kunu Lima], the three nearest the coast (Nggela, Wolojita and Mbuli) were the weaving areas. In the areas higher into the interior, weaving was forbidden by traditional law, a prohibition that remains unchallenged today (Hamilton 1994, 137).

When Roy Hamilton visited the non-weaving Lio mountain kampong of Pu’utuga in Ndona district, 7km inland and north of Onelako, he was told that weaving was banned. If a local woman should weave, a fierce storm would arise and destroy the village (1990, 196). Yet the people of Pu'utuga wore the same types of sarongs as the coastal villagers, but had little knowledge of the names of the patterns or the fine points of construction.

Villagers dressed in traditional costume

performing the gawi circle dance in Pu’utuga

Photographed by Cary Black in 1988

According to Maximus Wolo, the influential mosa laki tana pu’u of the Walo clan in Desa Saga, Kecamatan Detusoko, this prohibition still applies today. In the unlikely event that a local woman decided to take up weaving she would be politely requested to leave the village, since this activity would bring misfortune and illness onto its inhabitants. In the past this prohibition would have been enforced more harshly. Yet traditional Lio handwoven textiles, purchased from villages closer to the coast, still play a vital role in village life and culture. Women and men wear traditional lawo and luka sarongs and sémba shoulder cloths, while the payment of bridewealth – consisting of pigs, jewellery and money – is reciprocated with a counter-prestation of ikat and rice.

Young dancers in the non-weaving village of Saga dressed in traditional Lio textiles

The five main weaving zones in Ende Regency are:

- the Islamic Endenese coastal region laying to the west of Ende city

- the Islamic Endenese island of Ende in Ende Bay,

- the Catholic Lio coastal region of Kecamatan Ndona east of Ende, and the slightly inland region of western Ndona just northeast of Ende,

- the Catholic Lio coastal region of Wolojita, including the kampongs of Wolojita, Pora and Nggela and

- the mixed Catholic and Islamic Lio coastal region of Wolowaru, especially the kampongs on the east bank of the Mbuli River ranging from kampong Wolowaru down to Kapoone on the coast.

Return to Top

Historical References to Endenese and Lio Textiles

There is only limited historical information relating to the traditions of weaving and costume in the Ende region, especially concerning Nggela. Yet while the few nineteenth century reports referring to the Lio relate to Ndona, the home of the SVD Catholic Mission, it is likely that similar conditions and difficulties were experienced in more remote Nggela.

In 1855 P. J. Veth reported that merchants sailed to Flores from Sulawesi, probably Makassar, every February and March, returning in August or September. They brought gold, coarse porcelain, elephant tusks, parangs, red and blue linens and copperware, which they bartered for birds' nests, hawksbill shell, trepang, shark fins, sandalwood, cinnamon, rope, coconut oil and cotton, as well as all kinds of cloths woven in landschap Ende. The latter were highly sought after in the surrounding islands, while the cotton of Flores was highly praised (Veth 1855, 164).

The Dutch merchant and envoy from Makassar, J. P. Freijss, provided another early reference to textiles in the Ende region the following year (Freijss 1860, 526). After traversing Manggarai and Ngada in western Flores where he observed that the local women wove using blue yarns, he found that further east in Ende they used reddish brown thread - in other words morinda.

The geologist Wichmann visited the small Islamic settlement and commercial centre of Ende in 1888, which at that time consisted of a contiguous complex of twenty extremely dirty coastal kampongs. In the early morning the villagers visited the beach to defecate ‘decently covering the lower parts of the body with the sarong’ (Wichmann 1891, 218-219). Here the cultivation of maize was undertaken by slaves, while cotton fabrics made by female slaves provided a secondary source of income.

Return to Top

Samuel Roos 1877

While serving as the Dutch controleur of Ende during the 1870s, Samuel Roos documented some observations about the local Endenese and their costume. He noted that the local coastal Endenese were an ethnic mixture - formed through the intermarriage of the people of Ende with immigrants from Sumba, Bima, Sumbawa, Piedju (on Lombok) and Makassar, the Makassarese influence being the most dominant. Makassarese features stood out in both their clothing and dwellings (Roos 1877, 489).

Roos reported that the local women were industrious. Apart from housework, their usual occupation was the spinning of cotton into yarn and the weaving of garments, not for their own use but for export. Thousands of their sarongs were exported to the adjacent island of Sumba (Roos 1877, 491).

The dress of the more important Endenese consisted of trousers, sarongs and headscarfs, all checked, along with a chitsen kabaai (calico kebaya), usually of Makassar colour. The sarongs, trousers and headscarfs were all made from locally woven fabric. Those who travelled to Singapore purchased black cloth tubeskirts embroidered with gold or silver, priced at 25 to 40 guilders. These were worn on festive and special occasions along with a kris.

The lesser men were usually dressed in a coarse sarong, pulled up as high as possible under the arms, so that only the arms and a small part of the upper body were exposed. They also wore a checked headscarf. For special occasions they wore trousers and a jacket, either checked or striped.

The women wore a coarse home-woven sarong and a short sleeveless blouse, preferably of plain red cotton, which were sold by the Makassarese. Young women wore finer woven sarongs, costing from 12 to 15 guilders, along with a short baadje (loose shirt) of silk or other expensive fabric. Their arms were always bare. Women’s jewellery consisted of very coarse gold bracelets and ear studs.

Return to Top

Herman ten Kate 1891

The physical anthropologist Herman ten Kate visited the same Ende kampongs in late January 1891, arriving in Ipi Bay from Surabaya aboard the government steamship Zwaluw (Ten Kate 1894, 201). He had arrived at a time of an insurrection against the Dutch, led by Bara Nuri, an Endenese mosa laki from the mountain kampong of Woloare, just 3km north of the Ende kampongs. Bara Nuri had previously been involved in the lucrative Sumba slave trade. Having escaped following eight months imprisonment in Kupang, he had retreated to a heavily fortified mountain kampong close to Ende from where he could resume his raids on the nearby beach kampongs.

Kampong Ende photographed by members of the Siboga Expedition in 1900 (ende-32)

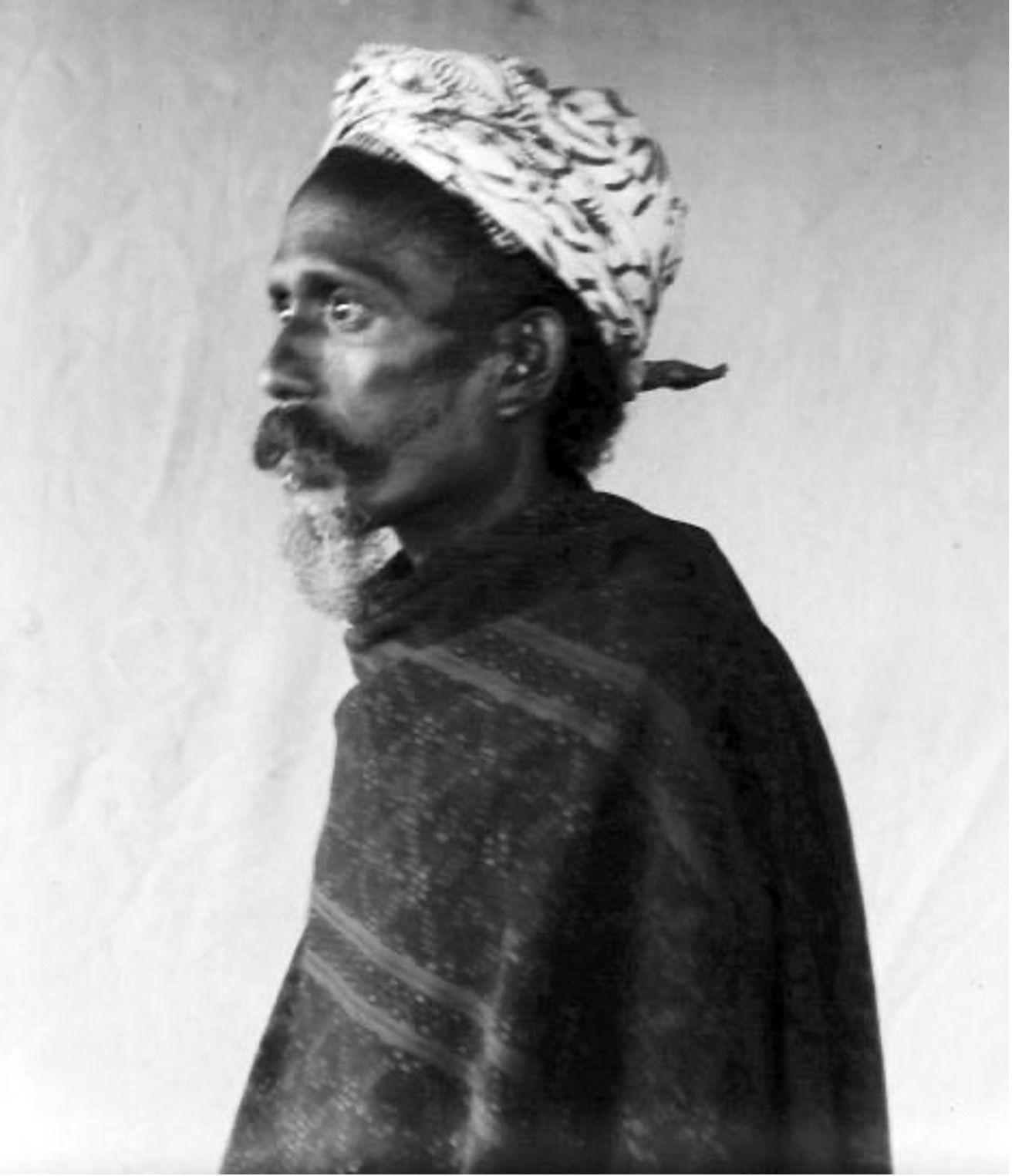

Ende consisted of a series of filthy, partially intertwined kampongs and the air was heavy with the smell of faecal matter, rotten fish and indigo. Ten Kate described the appearance of its residents:

Usually clad in fiery red or motley cotton in the manner of the Buginese and Makassarese, they look scruffy and ragged. Here and there, especially among the women, traditional fabrics are still worn. All go barefoot. In many old men the beard growth is quite well developed; yet the beard is usually kept short, so that a rough patch of stubble covers the dirty brown cheeks. The women, who don't look as mean as the men, wear the luxuriant hair in a twist with a wooden comb in it. Boys wear their hair cut short.

Clearly while some residents were wearing imported textiles, many local women were engaged in weaving:

.... the women were shy, and sometimes ran away from the loom under the houses as soon as we approached.

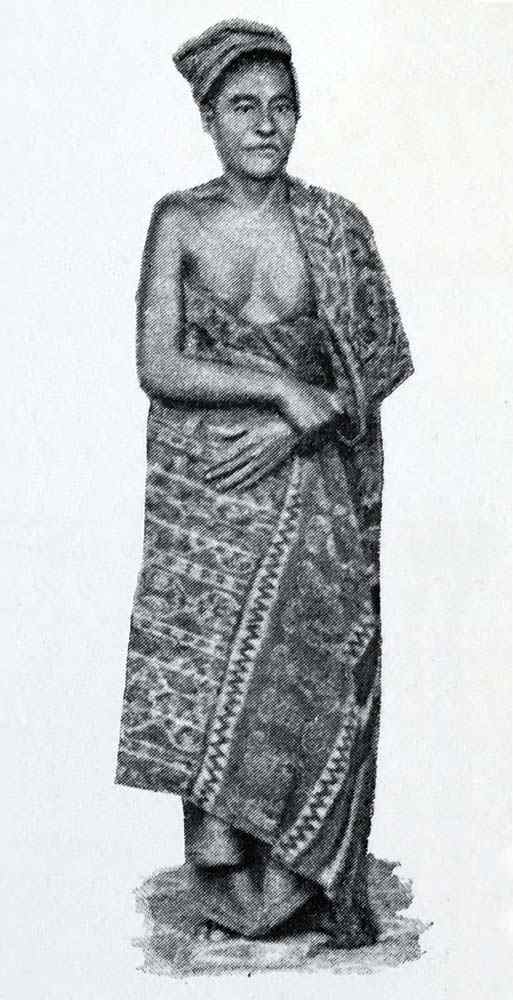

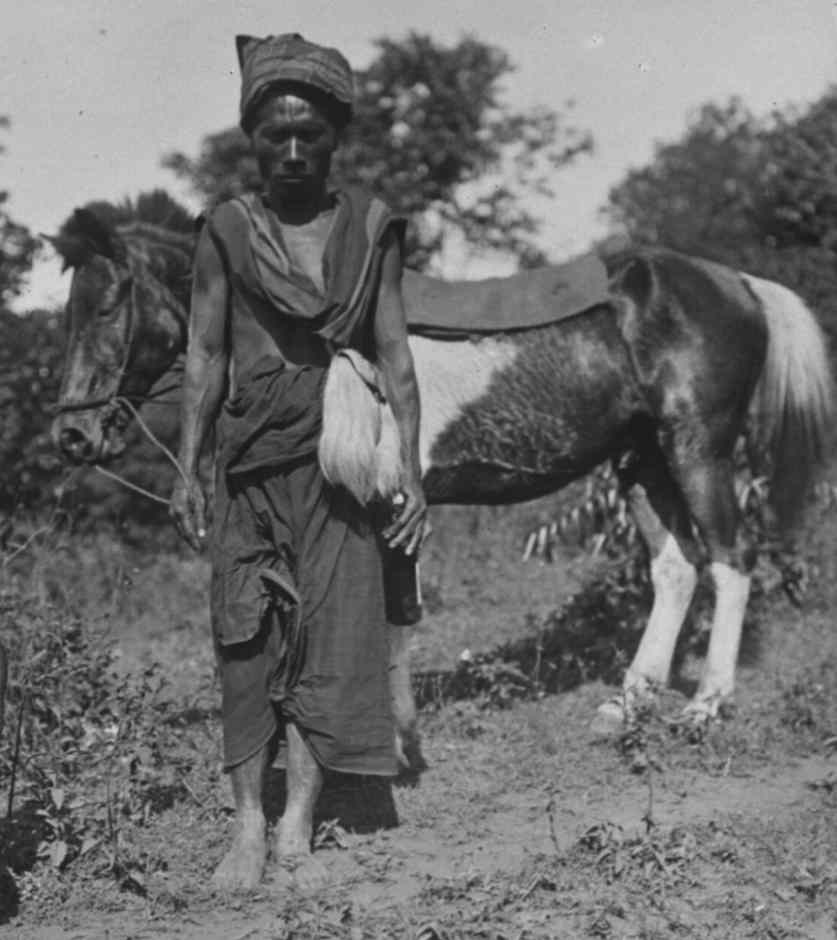

A little later in March 1891, Bara Nuri was persuaded to surrender and was transported to Kupang, where ten Kate had the opportunity to examine him anthropologically, along with Anggo Móló, the chief of Ekofeto in the Ngada region, who had attacked a Dutch geological expedition the previous year. Ten Kate left us a sketch of Bara Nuri wearing a large body wrapper, which was clearly not of Endenese or Lio origin, but might have been Timorese, especially given his location. He was later exiled to Java.

The Endenese rebel leader Bara Nuri in Kupang

Roy Hamilton suggested that Bara Nuri’s body wrapper, shown above, was ‘identifiably a predecessor of today’s [Lio] sémba shoulder cloth, although to us this seems a mistaken conclusion (1993, 273).

At the end of March, ten Kate left Kupang and sailed to Sikka Natal, where he stayed for eleven days during which time he made two excursions into the territory of the Ata Lio living in the far east of the Lio region. The first was to the mountain kampong of Tilang, located about 10km northwest of Sikka. Here ten Kate observed (1894, 217):

The hair and dress correspond chiefly to that of the inhabitants of Sikka. Some men wear a headscarf; others, whose hair permits, bear it completely outstanding. The women tied their hair up high.

Linen of European manufacture has even already penetrated this corner of the earth; especially black and blue cotton. However, cloth is also woven in Tilang.

Several days later he visited the Lio mountain kampongs of Kiara and Riipuang, where the appearance and clothing of the inhabitants was similar to those seen in Tilang.

Return to Top

Max Weber 1899-1900

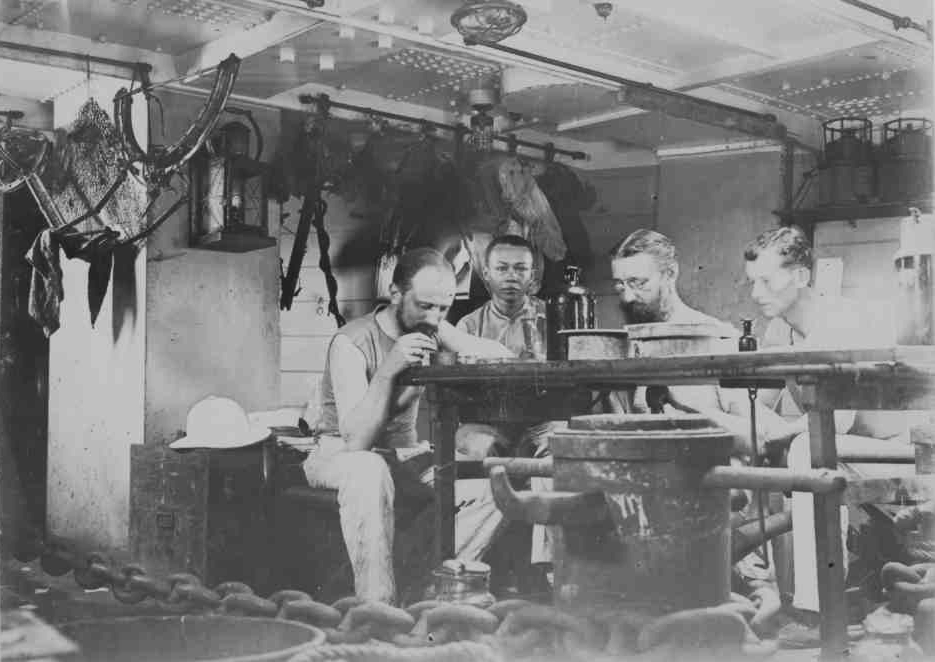

Dr Max Willhelm Carl Weber was the head of the Dutch zoological and hydrographic Siboga Expedition that from March 1899 to February 1900 explored many locations on the eastern part of the Indonesian Archipelago on a converted gunboat, the MV Siboga. Of the many monographs published by the expedition, one was an ethnographic review of Flores, which included a brief commentary on local clothing and jewellery (Weber 1900).

Max Weber, second from left, with three of his scientific colleagues abord the MV Siboga, September 1899

Unfortunately, Weber left us only a general overview of the topic, beginning by emphasising the enormous difference between the indigenous mountain people and the immigrant populations living in the coastal towns and settlements.

He described the Islamic Endenese living on the south coast as wearing a sarong, selendang shoulder cloth and Malay headscarf. Some even wore Buginese shorts. The better off often wore a jacket. The influence of the mountain population on local clothing was only slightly noticeable.

Unlike batik, warp ikat was a novel decorative technique for members of the expedition. Weber accurately described the method in relation to the sarongs of Sikka, which he described as rough and heavy. The basic tone was indigo with somewhat blurred white and red motifs and designs standing out. The sarongs are rough and entirely free of wax, which is related to the peculiar method of dyeing.

The white cotton threads … are suspended on a wooden frame in such a way that their length covers that intended for the future sarong. Then, here and there, pieces of plant fibre are twisted very tightly around a desired number of threads. These correspond to the required pattern of the sarong. If the entire mass is now dyed with indigo, the wrapped areas remain white, as they are inaccessible to the dye. When the threads are then hung side by side, they now represent the pattern of the sarong, white on blue; the dyer must therefore have the pattern of the future sarong in her mind. If she wants to add a third colour, she proceeds in the same way.

After the dyeing is complete, the entire mass of threads is stretched over the loom in order to be shot through.

As it is removed from the loom, the sarong has the shape of a sack. The original-coloured threads can be seen in the part that remains unwoven. After these threads are cut and trimmed, the free ends are sewn together. If it is to be a women's sarong, a second section is sewn onto the first one, resulting in a sack-shaped piece of clothing, open at both ends and longer than a man's, which the women nevertheless know how to wear very flatteringly. Sometimes it hangs on one shoulder so that only one arm comes to light, sometimes it is pinned over the breasts.

Weber did highlight a selendang body wrapper worn by the men of Ende. It was decorated with what was then, apparently, a popular pattern. The rather crude illustration given shows that it had a bold lateral tumpal end band. Such bands are always found on the luka sémba produced in Nggela but do not appear to have been used on Ndona or Endenese blankets for over a century.

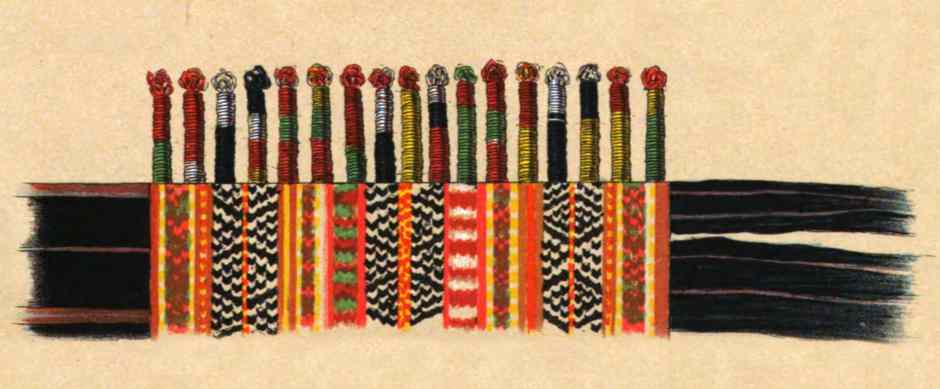

A detail of the selendang worn by the men of Ende, Weber 1890

He also illustrated the colourful, woven-in band on another selendang from Ende, the colourful fringes of which hung down on one side.

Detail of the multi-coloured end band on an indigo selendang

Weber’s monograph mysteriously included the image of an aristocratic Lio ceremonial bag called a pundi, but without any commentary. Such bags were used for holding siri-pinang (betel nut) and were made from a folded single length of cotton cloth decorated with supplementary warp, sewn up along both sides and sealed with a cylindrical metal clasp. The technique of supplementary warp has since become obsolete in the Ende region.

An aristocratic Lio man’s ceremonial pundi bag

Return to Top

Johannes Elbert 1912

From 1909 to 1911 the explorer and geographer Johannes Elbert led the Sunda Expedition through the islands of Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Wetar, Muna, and southeast Sulawesi. Although the focus of the expedition was botanical and zoological, Elbert did record that in Central Flores, cotton for domestic fabrics was mainly supplied by the districts of Nggela, Wolojita and Mbuli, while indigo came from Ende, Tanah Rea and Ndona (1912, vol. 2, 186).

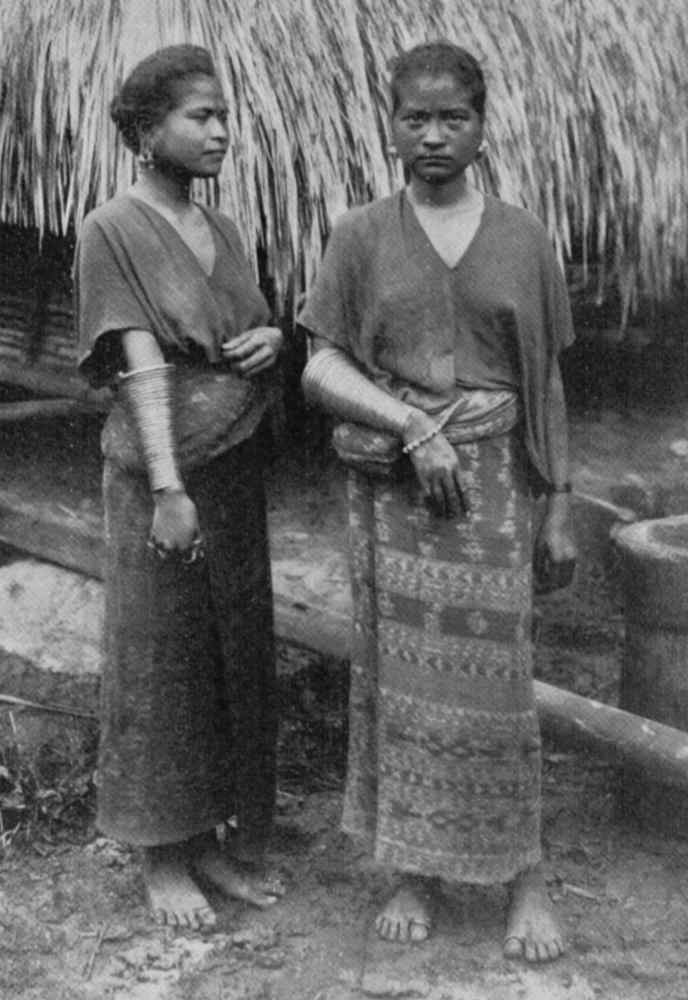

Sadly Elbert only recorded the costumes of the Endenese in the western landschap of Tanah Rea, ignoring the eastern Lio. There the women wore baggy, dark-coloured blouses with a v-shaped neckline, long sarongs richly decorated with ikat and rolled over at the waist, earrings and heavy spiral bracelets.

Two young women from Tanah Rea photographed by Johannes Elbert

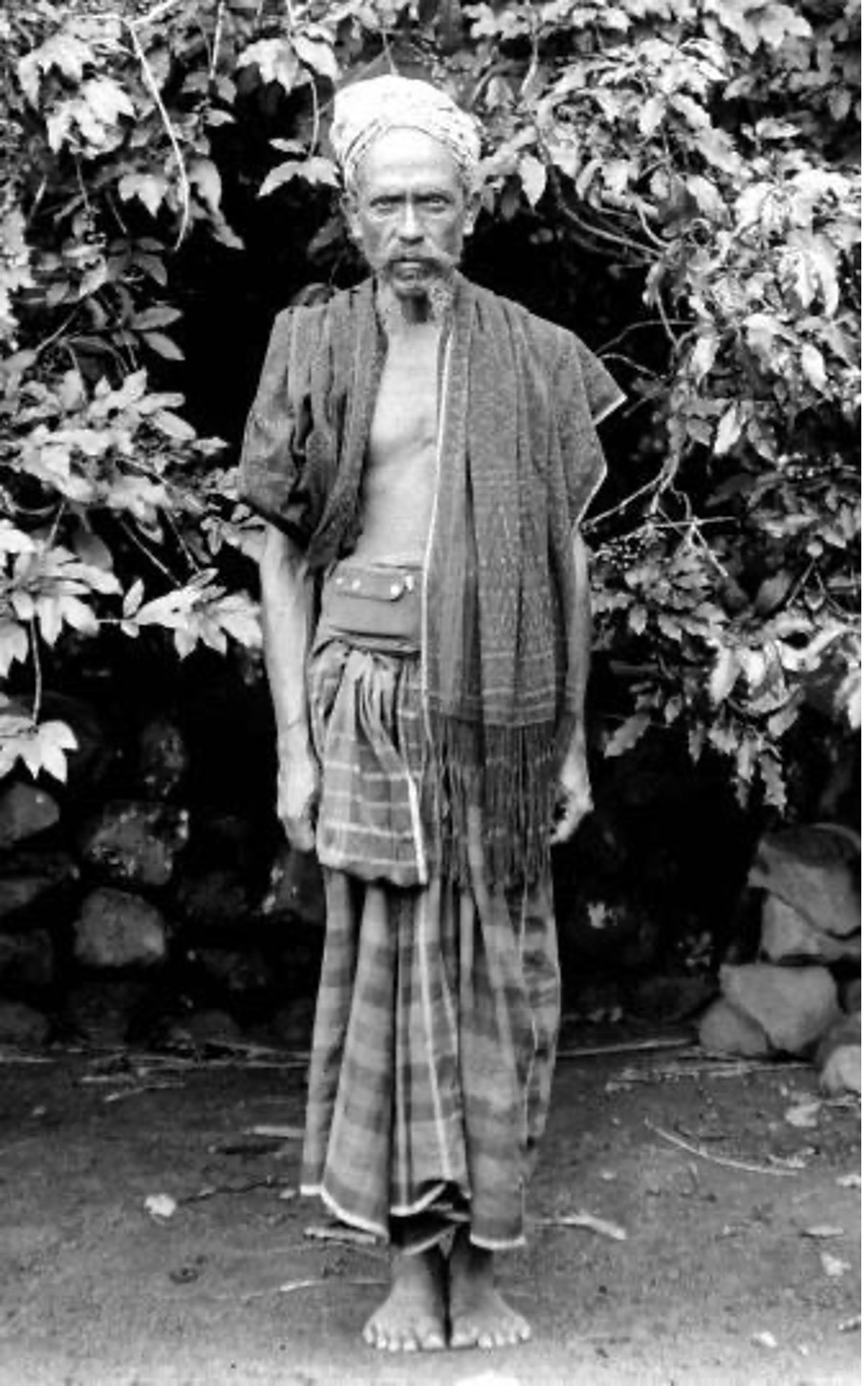

Elbert photographed a man wearing a long, striped sarong tucked up under a waist belt with an ikat shoulder cloth and a plain head cloth.

A man from Tanah Rea photographed by Johannes Elbert

In the mountain village of Puu Mere Wolo, about 6km inland from Ende Bay, Elbert photographed five young bare-breasted women wearing long ikat sarongs rolled down to leave a large bunch of cloth tied around the waist. Three wore pendant earrings, four wore simple bracelets, while the fifth wore a metallic spiral bracelet.

Five young women in kampong Puu Mere Wolo, landschap Tanah Rea

Elbert described the costume of the inhabitants of kampong Puu Mere Wolo as follows (1912, 184):

The [men] wear their upper bodies uncovered, but they roll up a large slendang (sémba) to protect themselves from the cold or when sleeping. They wear their hip wrappers (luka) loosely with the corner falling forward and often use a narrow, fringed belt. The women only wear a waist cloth (rawo). It is made of thick, home-woven cloth in beautiful, natural black, red, and orange colours decorated with square or simple spiral cruciform motifs, resembling the well-known beautiful examples from the island of Sumba. Such textiles are mainly made in the districts of Ende, Ndona, Nggela, Wolojita and Mbuli. Just as in Lombok, the women cover their upper bodies with a loose cloth with a neckline. They wear a heavy, spiral brass wire bracelet on their arms and many rings on their fingers and toes. They have large, peculiar earrings made of tin, silver and occasionally gold.

The men in the interior of the country seldom wear a headdress and, like the women, tie their long hair in a knot at the back of their heads. To hold up the protruding front of their frizzy hair, they occasionally wrap a strip of lontar leaf around the head or twist it into a bun over the forehead. The boys are often shaved except for a spot around the crown and are allowed to run around naked up to the age of 13 or 15. The women love to put long strands in their messy hair.

Because of the unstable situation remaining in some parts of Central Flores, the civil gezaghebber of Ende, Lieutenant J. J. de Vries, recommended that Elbert seek the assistance and protection of Kaka Dupa, a former rebel leader who the Dutch had won over by installing him as the Raja of Tanah Rea. Kaka Dupa was a Muslim belonging to the coastal Endenese who lived at Nanga Panda in Ende Bay along with his 19 wives. Elbert photographed Kaka Dupa with his eldest wife, who was wearing a blouse and a long sarong pulled up over her shoulders. Kaka Dupa wore a long luka along with a European striped jacket, an ikat sémba shoulder wrapper and a plain headdress.

Kaka Dupa, the Raja of Tanah Rea, photographed by Johannes Elbert

Return to Top

Charles Le Roux 1915-1919

While supervising the construction of the Great Flores Way during the period 1915 to 1919, the civil road engineer cum ethnographer Charles Le Roux photographed many local people along and close to its route during his sojourn on Flores. In the vicinity of Ende, he took many photos in the southern coastal Lio region.

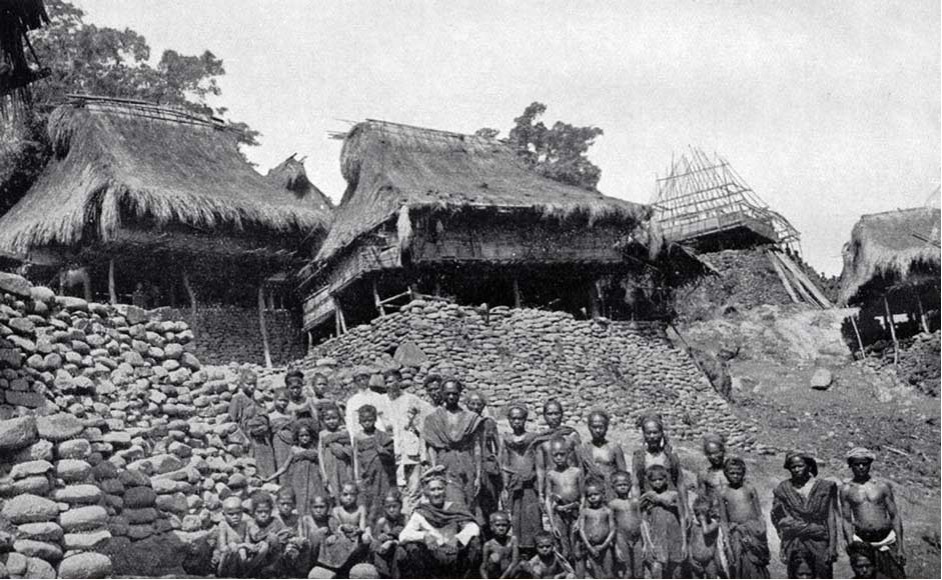

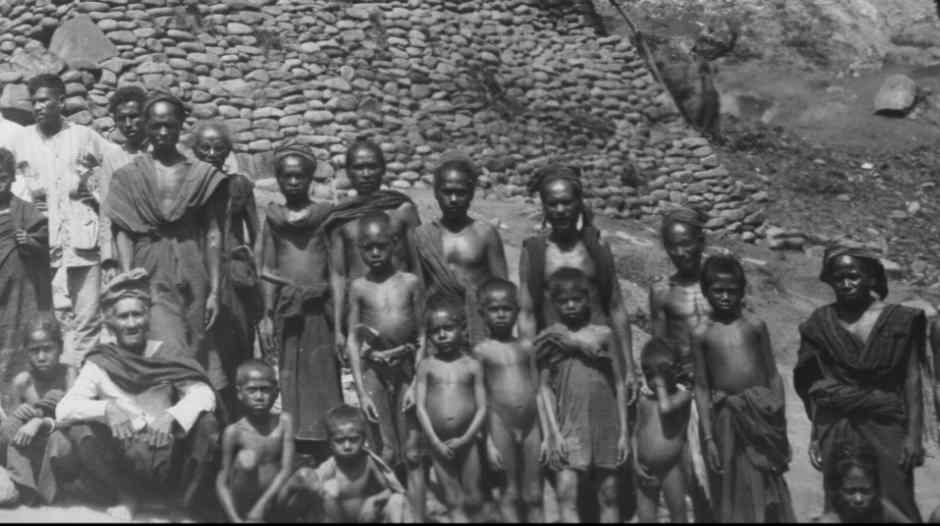

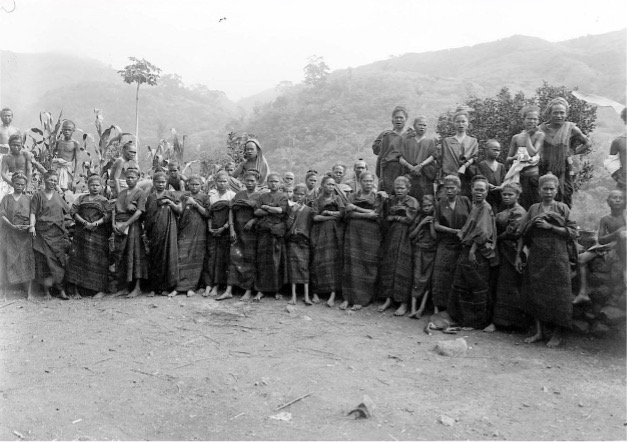

At the Lio coastal kampong of Wolotopo, 7½km east of kampong Ende, he photographed a group of villagers who were dressed in dark heavy cloth.

Kampong Wolotopo in Ippi Bay, Ende

Photographed by Charles le Roux, 1915-1919

All but one of the women and girls wore long ikat sarongs rolled up above the breasts, one partly pulled over the left shoulder. The one exception was wearing a long sarong rolled at the waist over a plain lambu blouse (see below). Two of the sarongs were decorated with multiple warp stripes bearing figurative motifs, but the others were decorated with narrow bands of warp ikat.

Women and girls at Wolotopo

Most of the men and boys were bare-chested and wore dark sarongs rolled at the waist, some plain, some warp-striped and a few decorated with simple warp ikat stripes. Many also wore shoulder cloths, suspended like a garland across the chest with the ends thrown over the shoulders, or in one case draped over one shoulder. Several of these shoulder cloths were decorated with warp ikat, although some were plain and one was warp striped. One young boy wore a loin cloth, but others were naked. Three men of apparently higher status wore white long-sleeved shirts.

Men and boys at Wolotopo

At Jopu, just north of Nggela, le Roux photographed another group of villagers standing in front of a drying rack hung with copra.

A group of Lio villagers in kampong Jopu

Three of the four women were wearing dark short-sleeved blouses with sarongs tied at the waist. The fourth woman had her sarong pulled up to her neck. Of the four sarongs, one was plain and the others were decorated with narrow bands of warp ikat. The two men were bare-chested and wore plain voluminous hip wrappers or sarongs, one light coloured the other dark. They both had patterned head wrappers and one wore a dark plain-coloured shoulder cloth.

Another photo taken by a bridge over a river between Wolowaru and Jopu shows two colonial officers and a local man wearing a white shirt and a white sarong with bold dark checks (see below).

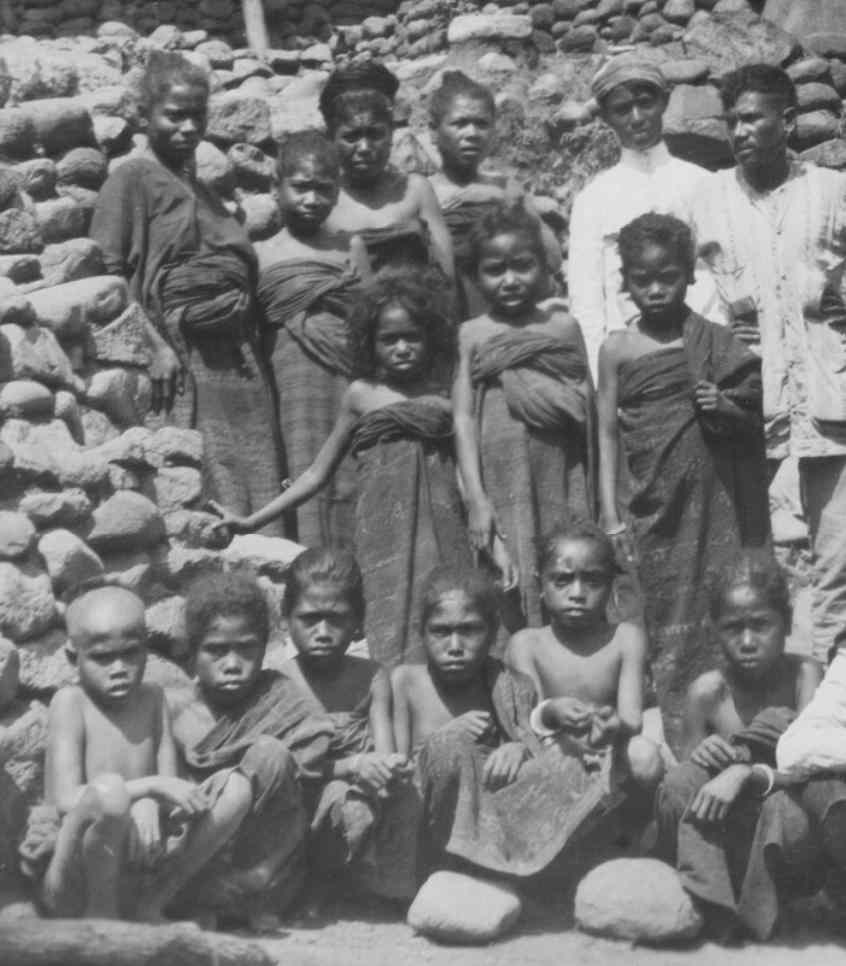

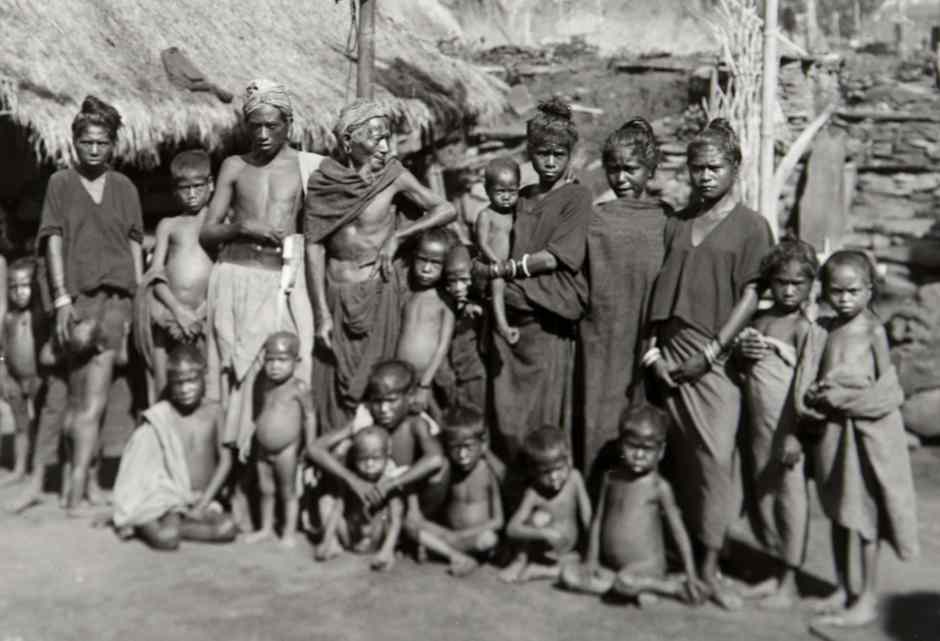

Charles le Roux photographed Lio villagers in the mountain kampong of Pemo, located on the southeast flank of Kéli Mutu and reached by a track that ran south from Moni on the Flores Way. It is not clear if this was then a weaving or non-weaving village, but apart from a naked boy, all of the inhabitants were fully clothed – the men in warp-striped luka, the women in long sarongs. Only one woman was bare-chested and she was nursing a baby in her arms.

Lio villagers in the mountain kampong of Pemo

dressed in sarongs and shoulder wrappers

Photographed by Charles Le Roux at some time between 1915 and 1919

Le Roux also visited and photographed a couple of places in or close to the Mbuli Valley just to the east of Nggela. One small series of images depicts the district chief of the Islamic kampong of Mbuli Wara Lau, along with his daughter and son.

Above and below: Linggo Gedo, the district chief of Mbuli Wara Lau

The chief is dressed in an imported light cotton checked sarong, a batik head cloth and a fringed ikat shoulder cloth decorated with a geometric pattern. His daughter is supposedly dressed in the costume of a mountain Endenese, while his son is dressed in typical Malay fashion.

Above: the daughter of Linggo Gedo district chief of Mbuli Wara Lau. Below: the son of Linggo Gedo. Both photographed by Charles C. F. M. Le Roux.

Le Roux also left us a fine image of the female residents of kampong Roga, located on the Flores Way just 2km east of Wolowaru in the upper Mbuli Valley. It is unclear if this was a weaving or non-weaving village. Nevertheless, the women were all well dressed in long warp ikat striped sarongs. They all wore plain dark-coloured blouses with v-shaped necks, some with overlapping openings at the front, others without.

A group of Lio women wearing ikat textiles in the

mountain kampong of Roga on the Flores Road

Photographed by Charles C. F. M. Le Roux at some time between 1915

and 1919.

Le Roux also photographed a group of women in the east Lio region carrying baskets and bags of rice to the local market. Unfortunately, the exact location was not recorded. All of the women were wearing plain, baggy, short-sleeved blouses that appear to be tailored from home-woven cloth. They all have dark sarongs decorated with bands of warp ikat, some with the same complex motifs we find in Lio sarongs today. One can clearly be identified as a lawo mogha, a design still in fashion now.

Above: A group of east Lio women carrying rice to

the local market

Below: Detail of a lawo mogha from the above image (far

right)

Finally in the west of Ende region, le Roux photographed the Endenese Raja of Tanah Rea, Kaka Dupa, this time standing beside three of his daughters.

The Raja of Tanah Rea, Kaka Dupa, with his three

daughters

Photographed by Charles le Roux, 1915-1919

Kaka Dupa was wearing a simple striped luka with a buckled waist belt, a European shirt and striped jacket, a large ikat sémba shoulder cloth with long fringes and a large headdress held in place by a woven band. His daughters were dressed in blouses, possibly silk, and long lawo tubeskirts decorated with ikat patterns that are similar to those still woven today.

Return to Top

Bertho van Suchtelen 1921

Bertho van Suchtelen had been based in Ende as the civil gezaghebber of South Flores from August 1910 until 1918. In 1921 he published some general remarks about the textiles of the Ende region.

Native cottonseed was often planted for growing cotton, which was used for making home-made textiles that were predominantly dyed with indigo. The latter was made with lime powder and precipitated into indigo cake. This was later reused by dissolving it in warm ash water (1921, 65 and 188).

Women wore a tube-shaped sarong, which was made in a very large number of types, each having their own patterns representing flowers, animals or clouds but mostly random figures, ‘the original meaning of which could no longer be ascertained.’ Simple clothes with no ikat work were used for daily wear, but ikat-decorated clothes were worn for visits and celebrations (1921, 203). Men often wore a hip wrapper, known as a ragi, and an ikatted multi-coloured shoulder cloth or sênai, which was loosely thrown over the shoulder or draped like a garland with the fringes thrown back over both shoulders (1921, 210).

Return to Top

Elisabeth Wilhelmina Viruly Verbrugge 1922

E. W. Viruly was an unmarried female amateur photographer who embarked on a tour of Indonesia from 1922 to 1923. While on Flores she visited the Kéli Mutu crater lakes, thanks to the assistance of a local kepala kampong. She left us a photograph of that village head, taken at a location between Pemo and Kéli Mutu, He was wearing a long, dark-coloured light-checked luka rolled at the waist, a dark-coloured, possibly plain shoulder cloth worn over the chest like a garland, a checked head wrapper and a goatskin bag. The image was reproduced in her book, Met de camera door Nederlandsch-Indië, published by J. H. de Bussy in Amsterdam in 1923.

The kepala kampong on the way to Kéli Mutu on 6 September 1922

Return to Top

Father Simon Buis SVD 1923

In 1923 two Dutch priests from the Catholic mission in Ndona, Father Simon Buis SVD and Father Piet Beltjens SVD, made a film called Ria Rago. Photographed in Onelako, Ndona, it is the story of a Catholic girl whose parents force her to become the second wife of Doki Dapo, a much older Muslim. After refusing to marry, she was beaten and fled to the mission but was captured by her father and taken back to her kampong. After months of torture and on the brink of death she again escaped to the mission where she was administered the last rites.

Although the plot was fictional, the scenes were photographed using local villagers within the hamlet of Onelako, providing a pictorial record of indigenous clothing at that time. Most of the women appear to be wearing locally made sarongs decorated with ikat, although one or two are made from undecorated dark-coloured, presumably home-woven, cloth. The ikat patterns appear to be simpler than some of those encountered today.

By 1923, none of the women were seen bare-breasted, a result of the influence of Catholic missionaries and the local Ndona Mission over the previous decade or so. All of the women seem to be wearing plain coloured lambu blouses with overlapping front panels, v-shaped necks and elbow-length sleeves. As noted by Hamilton, on Flores these blouses are unique to the Ende-Lio people, modelled on the baju bodo of South Sulawesi, probably introduced into the port of Ende by Makassarese immigrants and traders (1993, 274).

Above: The young heroine Ria Rago and two small

girls wearing simple ikatted sarongs

Below: Young dancers wearing lambu blouses and long

sarongs, four of which are decorated with warp ikat

Male costume was far more varied in 1923 than it is today, with many men wearing checked hip wrappers, which might be home-woven or made of imported cotton cloth. According to Hamilton, these were black and white luka bara mité (‘sarong white black’), which remained the most common garment for everyday male wear until the 1960s.

Two men, one Muslim the other not, wearing luka bara mité

One man is seen wearing what appears to be a dark, locally-made, probably indigo-dyed, hip wrapper with large checks. Such textiles were woven in a balanced weave on a loom incorporating a reed. Some men are topless, while others wear a shoulder cloth. A few have collarless shirts, both short and long-sleeved, while one wears a white vest. One ikatted shoulder cloth is identical to the luka sémba that is still being made in this village today.

Above: One man with a white luka (left)

and another with a bold checked luka (right)

Below: The luka sémba shoulder cloth worn by the man

seated to the right

The film also contains a scene with the senior mosa laki of Onelako, Ragho Dao, who is not wearing a tubeskirt but an ikat hip wrapper made from a flat rectangular cloth along with a similar ikat shoulder cloth. Hamilton informs us that this style of dress was reserved for ata nuwa. These were prominent leaders who had undergone a painful and prestigious ritual called nuwa, which involved a longitudinal incision of the penis (1993, 271).

Above: The mosa laki Ragho Dao, left, wearing an ikat hip wrapper and a similar ikat shoulder cloth

Return to Top

Raymond Kennedy 1949-1950

In 1949-1950 the American anthropologist Raymond Kennedy made most of his enquiries in the Ende region in the kampongs of Rewarangga and Roworeke in the Ndona Valley, about 5km northeast of the administrative centre of Ende (then Endeh). Here most of the population was Catholic.

Unfortunately Kennedy was obsessed with social anthropology and generally showed little interest in weaving or textiles. He noted that there were no specialist artisans in these kampongs at all, and there was a very low level of craftsmanship in all things apart from weaving (Kennedy 1952, 215). Textiles played an important part in the gift exchange in marriage, with the man giving male items such as animals, gold, money and tusks, and the woman responding with female items, namely cloth, mats, rice, etc. (Kennedy 1952, 147).

Regarding textiles and weaving, it seems that local weavers still had no access to commercial machine-spun cotton (Kennedy 1952, 217):

The women no longer wear the homespun blouses. They wear homespun sarongs like the men do, but buy kebaya of thinner cloth today.

They cannot make thin cloth with their looms, and this is a great handicap. What they make is too heavy. This is mainly a matter of thread. They can’t spin thread any thinner than they do and have it strong enough so that it will not break on the loom. Thus, if they could get trade thread, they might be able to weave thinner cloth.

Every woman spins thread and weaves. There are no specialists, however, who sell cloth. This is done only rarely.

Kennedy then added (1952, 219):

Women now use bought cloth to make thin kebaya. Formerly they made blouses of homespun, but these are all gone. Men and women still wear homespun sarongs. Men wear this alone and are usually bare above the waist. If a man wears a selendang, he is a big man. If he wears a shirt, this is really very slick attire. There were no shoes here at all before, and few now.

Men and women wore earrings before, the men ones of gold (look like silver) which the pagans still wear, and the women ones of a different style. … Beads are worn by men and women on festival occasions. These are great ceremonial objects and are worn by the people who are proud of them. If one is not entitled to them. He will become sick if he wears a string of beads.

Regarding cotton yarn (1952, 221):

I asked about the cloth situation. This is a poor case now as everyone is short and the distribution of cloth by the government has not been too effective. This is a remarkable case. For many years formerly the people here had discontinued planting cotton. Then, when the Japanese came, they started up again and have done so since. Each family plants a little. The yield is not so good, but it could be, the assistant says. Some cotton fluff is sold in the pasar. Thread, however, is not usually bought any more. It is rare and expensive. Thus the wheels and even the spindles are busy everywhere.

Return to Top

Roy Hamilton 1989

During the late 1980s Roy Hamilton conducted research in Onelako, Manulondo, Wolotopo and the non-weaving village of Pu’utuga for his 1989 MA Thesis on the textiles of the Ende-Lio region. He resided in Ende City, from where he travelled daily out to the nearby Ndona villages.

His most elderly informants recalled that in the past, women who were commoners or slaves mostly wore plain garments, which if coloured were dyed with simple plant or mud dyes. The processes of ikat binding and dyeing with morinda were restricted to a minority or aristocratic women. These traditions had already begun to erode prior to the Dutch take over in 1856, probably as a result of the influence of the entrepôt port of Ende. Whereas virtually all cloth woven in the Ndona region in 1923 was from hand-spun cotton, by the 1930s the latter was becoming widely superseded by commercial cotton yarns.

Hamilton found that well-to-do weavers tended to make naturally dyed sarongs to be worn by family members, or used as bridewealth counter-prestations. Other weavers made sarongs for both their families and for sale, the most accomplished producing naturally dyed sarongs under commission, others making synthetically dyed sarongs for sale on the market.

Ndona weavers remained very conservative in their preference for traditional lawo types, most of the motifs of which were analogous to the full range of motifs found on the lawo made by the Endenese living to their west. The only example of design innovation was a sarong created in Onelako during the 1930s by an aristocratic woman called Teresia Sue. Now known as the lawo oné mésa, it is completely covered with diamond-shaped motifs.

In the 1970s the designs of men’s luka sarongs changed to those seen today, with a dark blue or black ground decorated with bold-coloured warp bands. However, while these were worn in the villages every day, Western dress prevailed in Ende city.

Return to Top

Willemijn de Jong 1987-2022

The Dutch-born anthropologist Willemijn de Jong first visited Flores in 1985. Thanks to a chance encounter with a weaver from Nggela in August 1986, she decided to focus her studies on that village. In 1987 she began a two-year project of postdoctoral field research in Nggela at the University of Zurich, supported by the Canton of Zurich under the auspices of Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia (the Indonesian Institute of Sciences), Universitas Indonesia in Jakarta and Universitas Nusa Cendana in Kupang.

She returned to Nggela from 1990 to 1991 and has been returning to the south Lio region on a regular basis ever since. Between 1993 and 2001 she sponsored a micro-credit project to encourage over a dozen of the best local weavers to make naturally dyed sarongs. During her time on Flores, de Jong assembled a collection of over 200 Lio textiles, some of which were exhibited at the Museum de Kulturen in Basel in 2016.

From her many discussions with local weavers, de Jong has attempted to establish the development of clothing and weaving in Nggela during the twentieth century.

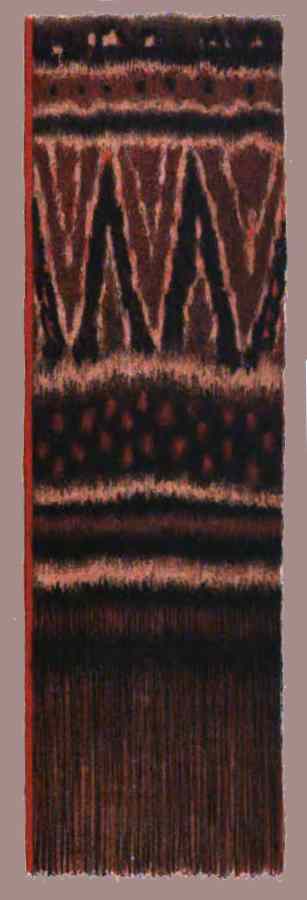

According to local adat experts, the very first type of Nggela ikat sarong was the simple lawo népa nua, decorated with multiple horizontal bands of simple geometric motifs (de Jong 1994, 222). Later, probably during the nineteenth century, sarongs with decorative centre panels such as the lawo redu emerged, most likely created by noblewomen for their own exclusive use. The designs were influenced by the layout and patterns on prestigious Gujarati patola retained as village treasures, having been gifted to senior mosa laki leaders during the eighteenth century by the Dutch. As their monopoly on these designs was eroded by the non-aristocratic weavers, these elite noblewomen were spurred into creating even more complicated designs such as the lawo mogha and later the lawo sémba.

The introduction of taxation in 1911/1912 by the Dutch colonial authorities in Ende led to a gradual transformation in the local economy (van Suchtelen 1923, 13). Sometime later, machine-spun cotton yarn became available - but only the wealthiest high-ranking women could afford to purchase it. By 1917 the average taxpayer in the Ende region paid 3.64 Dutch florins per annum – about US$1.50, equivalent to US$30 today. Commoners were increasingly forced to weave and sell non-ikat textiles to pay their taxes, giving them little time to spend binding yarns to produce ikat.

Women wore everyday plain black sarongs made from commercial cloth, or white sarongs with black checked squares, just like the lawo bara mité worn by the men (de Jong 1994, 223). Ikat sarongs were rather rare, and restricted to the female aristocracy.

During the 1930s Nggela weavers began to regularly use commercial yarn for the warp, reserving hand-spun yarn for the weft. By now the increasing influence of the Catholic church was leading to the erosion of local beliefs. After the 1930s weavers ceased to produce the sacred beaded lawo butu.

Prior to 1945 de Jong estimated that the number of different types of ikat sarong was limited to just six, some with horizontal stripes and some with central field patterns (de Jong 2020b, 2). At that time most women owned only two ceremonial sarongs, one for church and one for village ceremonies. In everyday life women wore a black sarong tailored from commercial cloth, and men wore a handwoven white sarong (de Jong 1994).

With the granting of independence in 1949 and the introduction of democratic local government in 1954, the mosa laki lost their political role. In turn the noblewomen could no longer retain their monopoly on certain types of cloth. During the 1960s local weavers introduced some of the most important Nggela designs, notably the lawo kéli mara and the vertically designed lawo pundi. Yet at this time, prior to the introduction of chemical dyes, and when yarn was still partly hand-spun, weavers still produced only a few pieces of cloth per year.

The increasing availability of commercial machine-spun yarn in the 1960s, followed by the introduction of synthetic dyes in the mid-1970s, made it far easier and faster to produce an ikat sarong and encouraged the development of an ever-increasing number of new ikat designs (de Jong 2020a, 25). Since the second half of the 1960s weavers have exclusively used machine-spun yarn, increasingly in the form of rayon rather than cotton (de Jong 1994, 213). Since the mid-1970s most local cloth has been dyed with synthetic dyes or a mixture of synthetic and natural dyes.

Between 1945 and the 1970s Nggela weavers became more innovative and created many new textile designs, although some were based on earlier patterns used by the Endenese. De Jong worked out that by the 1970s, there were thirty-three different types of hand-woven clothing being produced in the kampong. This included some twenty different types of ikat sarongs. After the introduction of chemical dyes in the mid 1970s, even more new patterns emerged. From then onwards, the most skilled ikat binders knew how to produce all of the then known designs, regardless of their social status.

Starting around 1975, two or three weavers in Nggela began to produce lawo gamba – sarongs completely decorated with pictorial motifs, including the tree of life, sacred snakes, gold jewellery and Ine Mbu, the mythical rice goddess. Willemijn de Jong believes these were inspired by the 1969 book Nusa Nipa (Snake Island), written by the Catholic priest Pater Piet Petu SVD (aka Sareng Orinbau), which included drawings of the rice myth, ritual objects and snakes. Soon other weavers began to produce their own versions, which were quickly snapped up by dealers and foreign tourists who began visiting the village during the 1980s.

During the 1980s many weavers began to switch to the use of rayon rather than cotton, which being cellulose-based has similar properties to cotton although is resistant to dyeing with morinda.

Thanks to the increase in productivity achieved by the use of commercial thread and commercial dyes, by 1988 it was possible for many women to own up to ten woven sarongs (de Jong 2020b, 2). By the 1990s weavers were able to make around fifteen pieces a year with a mix of about six women’s sarongs, two men’s sarongs, five shoulder cloths and some small scarfs. Chemical dyes were not just preferred because they were far less labour intensive to use, but also because the quality of the ikat patterns was more precise and the chemically dyed cloth had a smoother texture and was more comfortable to wear.

In 1993 Willemijn de Jong launched the Proyek Lawo Kembo (Morinda Sarong Project) initiative aimed at encouraging local weavers to keep alive the tradition of producing textiles using natural indigo and morinda (kembo). Weavers could obtain a micro-loan to purchase materials and were given a guarantee that one of the two or more cloths they produced would be purchased (de Jong 2016b, 54). The initial project ran in phases between 1993 to 1999 and was extended with a final two-year phase to 2001. As a result, some of the younger weavers were encouraged to become skilful in the use of natural dyes.

Return to Top

Conclusions

It is clear that even in the mid-nineteenth century, the weavings of the Ende region were highly valued, being exported to neighbouring islands, especially Sumba. The main weaving regions were the landschaps of Ende, Ndona, Nggela, Wolojita and Mbuli, all located close to the southern coast.

At that time the costume of the so-called pagan mountain villages was markedly different from that worn by inhabitants of the Islamic kampongs of Ende, the latter heavily influence by Makassar. It seems that spinning cotton and weaving were major female activities at this time, not just for domestic consumption but also for export. Some of this activity was also performed by female slaves. Local women wore heavy cotton tubeskirts and short-sleeved blouses, while the men wore long hip wrappers pulled up to the arm pits. For formal attire, the high-status men dressed in colonial inspired jackets and trousers.

Thanks to Johannes Elbert, we have a pictorial record of the textiles worn by the western Endenese living in landschap Tanah Rea during the early 1900s. Here women also wore long, heavy sarongs decorated with bands of warp ikat, often rolled down to the waist. While some went bare-chested others wore baggy, dark-coloured blouses with a v-shaped neckline.

Among the southern coastal Lio everyday clothing seems to have been quite simple, consisting of lawo tubeskirts, luka sarongs and sémba shoulder cloths. These were mostly made from plain cotton and were often dyed a dark colour using either indigo or tannins mordanted with stagnant ferrous mud. Textiles decorated with ikat were rare and high-status, the preserve of the tribal aristocracy – the mosa laki and their wives. Commoners and slaves were most probably forbidden to wear such textiles.

Traditionally Lio women went bare-breasted, but following the establishment of the Catholic Mission in Ndona in 1916 they were encouraged to cover up, adopting the design of the Makassarese baju bodo blouse. It is probable that these lambu blouses were initially made from home-woven clot,h but not long afterwards from lighter imported cotton cloth.

Nineteenth century ikat designs seem to have been just as complex as those produced today, although their number was probably limited. Thanks to the introduction of commercial cotton yarns in the 1930s, and chemical dyes following independence, the number of ikat patterns began to increase from the 1950s onwards.

Men’s luka hip wrappers were either plain or checked, the latter being either the popular black and white luka bara mite or indigo-dyed luka decorated with large subtle checks. It was not until the 1960s and 70s that the warp striped designs seen today became fashionable.

The widespread adoption of rayon in the 1980s discouraged the use of morinda in favour of synthetic dyes. The preference for pre-dyed yellow or orange rayon combined with black chemical dye gave rise to a new harsh style of lawo tube skirt, with complex designs rendered with a monotonous yellow hue, rather than the subtle natural colouring of old.

A selection of modern yellow and black Lio lawo on offer at the weekly Moni bazaar

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 8 February 2024.