Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Eastern Flores

Kecamatan Demon Pagong

Origins and Early History

Early Colonial History

Demon Pagong in 1915-1919

Demon Pagong in 1929

Demon Pagong in 1950

Ethnography

Bibliography

Eastern Flores

The eastern end of 320-kilometer-long Flores Island curves northwards and back on itself like the tail of a scorpion, enclosing Hading Bay. Some have likened Flores Island to a snake with a western head and an eastern tail. The Catholic priest and anthropologist Pater Piet Petu SVD believed the original name of Flores was Nusa Nipa, meaning Snake Island (Sareng Orin Bao 1969).

Space shuttle image taken in 1994 of the curved eastern tip of Flores Island seen from the northeast with the eastern islands of Solor, Adonara and Lembata.

Image courtesy of NASA.

As a whole, Flores Island is mountainous and covered in lush forests although the ruggedness of the landscape reduces from the west to the east. Even so, the eastern end is the location of two major stratovolcanos – active Ilé Lewa Tobi (1,703m) and dormant Ilé Mandiri (1,484m). Most of its inhabitants gain their subsistence from agriculture (mainly swidden) and, to a lesser extent, fishing.

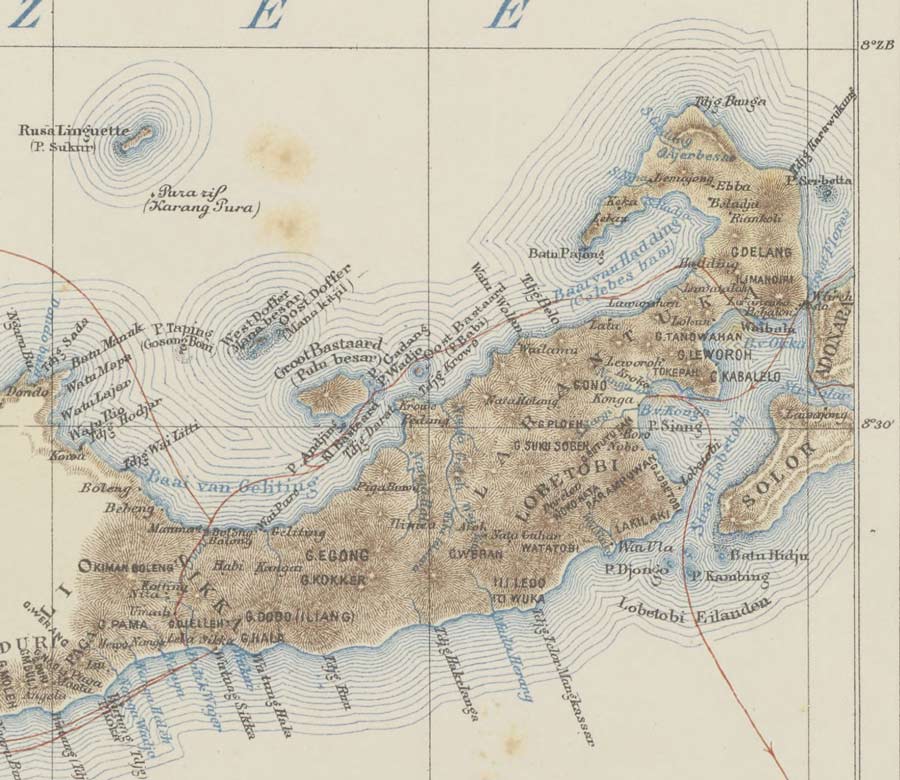

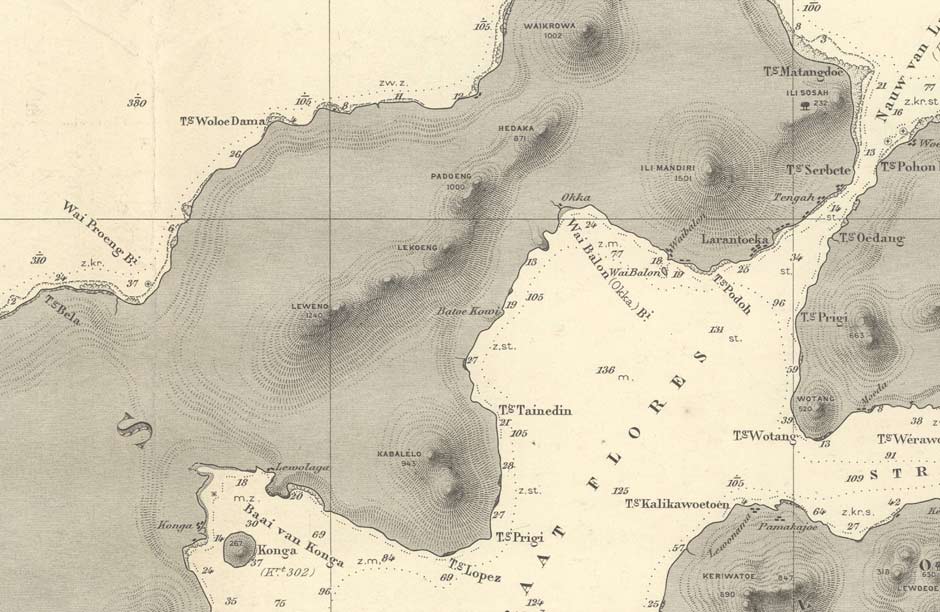

Detail of eastern Flores from a map of Flores Island.

Made by A. Wichmann in Utrecht in 1890.

Politically the eastern part of Flores as well as the eastern islands of Adonara and Solor are governed by Kabupaten Flores Timur (the Regency of East Flores), referred to locally as Flotim, headquartered in Larantuka. This is divided into nineteen kecamatan or districts, eight of which are situated on Flores Island.

Return to Top

Kecamatan Demon Pagong

Demon Pagong is one of the eight mainland kecamatan of Kabupaten Flores Timur. Located roughly 10km west of Larantuka, it stretches across Flores Island from Oka and Konga Bays in the south to Hading Bay and the Flores Sea in the north. It is bordered by kecamatan Titihena to the west and kecamatans Lewolima and Larantuka to the east.

Demon Pagong has two prominent volcanic mounts – Ilé Leroboleng (1,117m), also known as Ilé Lewero, in the centre and Ilé Kawalewo (941m) in the south. Its landscape is heavily forested with the exception of the lower slopes of Ilé Kawalewo. It has a land area of 57 square kilometres. The administrative and cultural centre is kampong Lewokluok.

Ilé Leroboleng had several explosive eruptions in the late 1800s and was seen to have another short eruption in 2003. Ilé Kawalewo has probably been dormant for millennia.

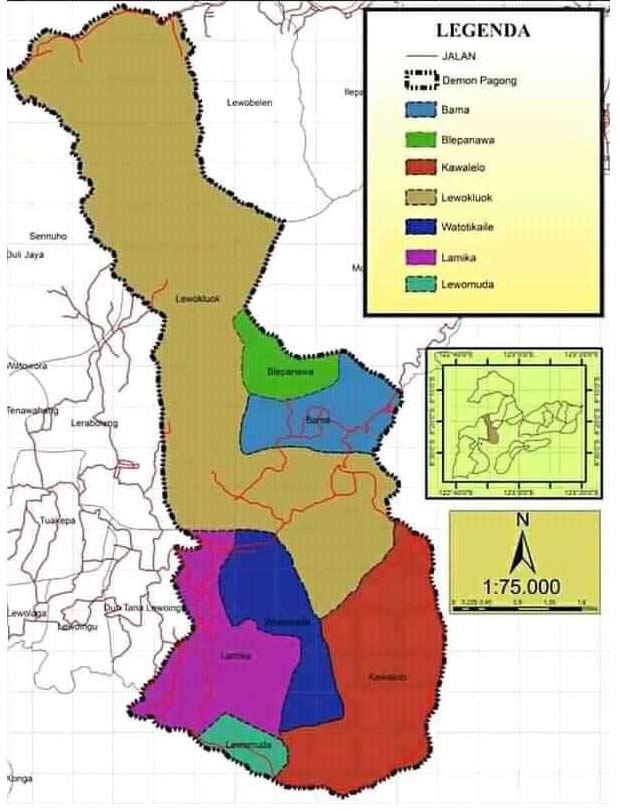

Kecamatan Demon Pagong and the coastal village of Bama

Demon Pagong is subdivided into seven desa or village regions:

| Desa | Administrative Kampong |

2019 Population |

| Lamika | Lamika | 714 |

| Kawalelo | Kawalelo | 617 |

| Watotika Ile | Watotika | 516 |

| Ile Lewokluok | Lewokluok | 1,229 |

| Blepanawa | Blepanawa | 432 |

| Bama | Bama | 655 |

| Lewomuda | Lewomuda | 284 |

| Total | 4,447 |

The seven desas of Demon Pagong. Lewokluok is mustard yellow, Blepanama is green and Bama is light blue.

The total population of Demon Pagong in 2019 was a mere 4,447, divided into 2,119 males and 2,328 females.

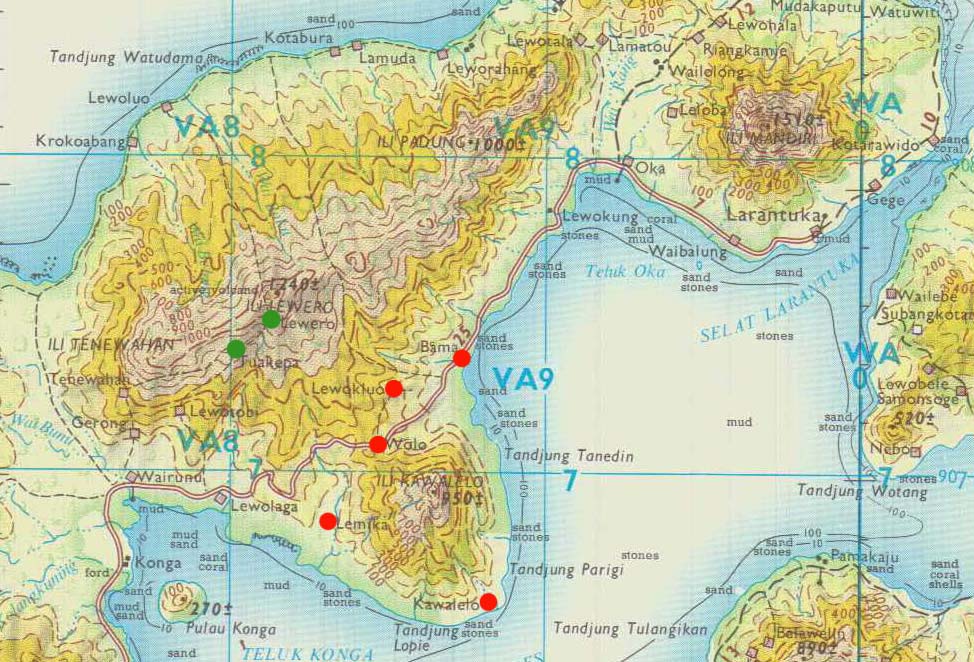

Some of the main kampongs (marked in red) in Demon Pagong

The trans-Flores highway (formerly the Flores Way) passes westwards from Larantuka in the wide low-lying valley that separates the two upland regions of Ilé Leroboleng to its north and Ilé Kawalewo to its south. Four of Demon Pagong’s kampongs lie close to the highway – Lewokluok, Blepanawa and especially Watotika (Wolo) and Bama. Kawalelo lies on the south coast facing Solor Island. Lamika and Lewomuda lie just west of Ilé Kawalelo in a valley opening out into Konga bay. The highland areas are unpopulated.

There is no road linking the south of Demon Pagong to the coastal hamlets on the north coast facing Hading Bay and Tanjung Bunga, such as Lewoluo and Koliwutun, which fall within the village territory of Desa Lewokluok.

The three main weaving villages of Demon Pagong and the volcanic mounts of Ilé Kawalewo (left) and Ilé Mandiri (right). Image courtesy of Google Earth.

The local economy is almost completely dependant on agriculture, the main cash crops being cashew nuts, cocoa, coconut and pecan nuts. In 2019 the region produced 898 tons of cashew, 424 tons of coconut, 59 tons of cocoa and 16 tons of pecan (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur 2021).

Local fishermen landed 226 tons of fish. Rice farming is limited to a tiny 10 hectares within Desa Bama. The main livestock are chickens, pigs and goats. A few cattle are raised in Kawalelo.

Located close to the major Catholic stronghold of Larantuka, the whole kecamatan is strongly Catholic. None of its residents are Muslim.

Above: The huge Catholic church of Saint Maria Immaculata on the Trans-Flores Highway at Bama. Below: The Catholic church at Blepanawa.

Return to Top

Origins and Early History

Anatomically modern humans (AMH) first reached island southeast Asia tens of thousands of years ago. Analysis of genetically human AMH teeth excavated from the Lida Ajer cave on Sumatra suggests that they date between 73,000 and 63,000 years before present (Westaway et al 2017).

We have yet to discover when they first crossed the 20-km wide Selat Strait to reach the islands of Komodo and Flores. However a long sequence of human presence has been discovered at Liang Bua cave close to Ruteng in western Flores. This was initially occupied by the small-bodied species known as Homo floresiensis but evidence of modern human occupation has been found in the upper layers of Liang Bua. While the date of boundary between modern humans and Homo floresiensis is yet to be established, the excavation team estimate this to be around 50,000 years before present (Sukikna et al 2016).

For much of the period since, this small population of Palaeolithic Melanesians occupied Flores alone. It is likely that the more sheltered bays of East Flores offered favourable sites for hunting, gathering and fishing communities. Large amounts of shellfish remains occur at most of the late Pleistocene coastal sites in the islands east of Bali (Wallacea), suggesting that this was the major marine resource for early modern humans.

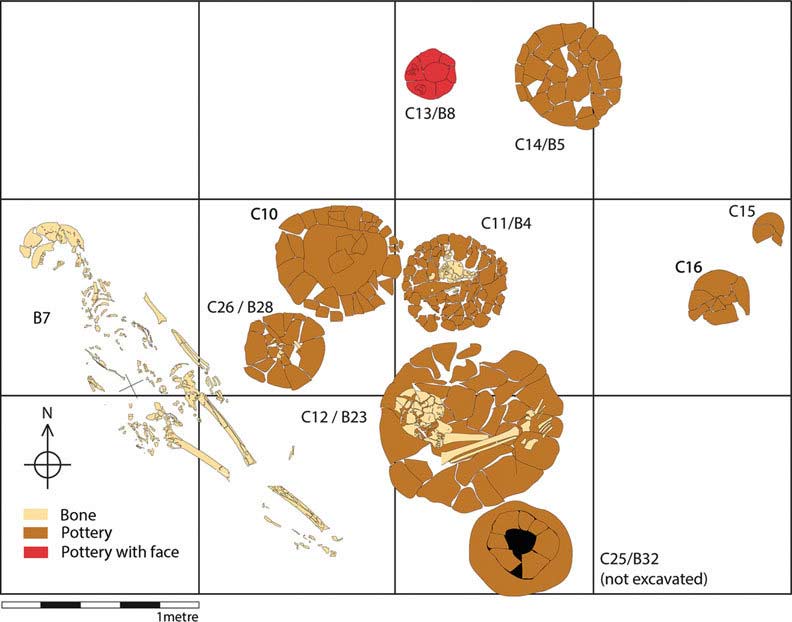

At some time prior to 1000 BCE small waves of Austronesian farmers began to arrive and settle in eastern Flores. Archaeological evidence suggests that Austronesians reached eastern Indonesia around 2000 to 1500 BCE (Bellwood 1997; Spriggs 2003). A combination of evidence suggests some migrated eastwards down the Malaysian/Indonesia Archipelago, while others migrated southwards down the archipelago of islands that run from the Philippines to north Sulawesi. Human bones recovered from the Neolithic ceramic urn burial site of Pain Haka, located on the north coast of Hading Bay close to the western tip of Tanjung Bunga, have been dated to the period 1200 to 600 BCE, showing that Austronesian groups were well established in East Flores by 1000 BCE and performing their ritual burials (Gallipaud et al 2016; Cochrane et al 2012).

Above: the location of Pain Haka Bay. Below: plan of a section of the excavations at Pain Haka showing broken funeral urns and human remains. Hudjashov et al 2017

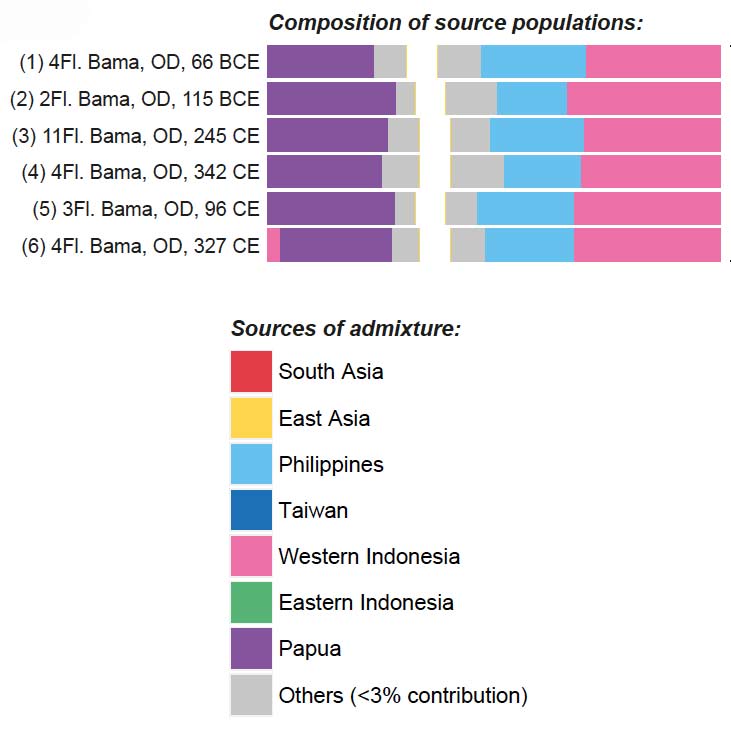

Linguistic analysis suggests that the local Austronesian language, Western Lamaholot, originated on Lembata Island and then migrated to Adonara and Solor and finally East Flores (Fricke and Klamer 2018, Fricke 2020). This suggests a migration of some Austronesian people westwards onto the Flores mainland. The Lamaholot language contains features that indicate strong Melanesian influence, suggesting a merger of languages as the early Melanesian and Austronesian populations mixed (Klamer 2012, 72). Genetic analysis of a sample of 28 villagers from Bama in Demon Pagong shows a clear mix of Melanesian (Papuan) and Austronesian DNA (Hudjashov et al 2017). The source of Austronesian DNA is Western Indonesia and, to a slightly less extent, the Philippines. It is possible therefore that the ancestors of the Austronesian population of Lembata arrived via the Philippines and Sulawesi.

The dates of genetic admixture (indicating interracial marriage) are much more recent than 1000 BCE, ranging from 115 BCE to 342 CE.

The genetic admixture of samples of DNA from Bama. Hudjashov et al 2017

However other Austronesian groups must have migrated eastwards into East Flores from the west, from a mythical location in the west described as Sina Jawa. When Ernst Vatter visited Bama in 1929 he was told that the founding clans who retell the oral narratives are all believed to have arrived from Sina Jawa (1932, 141). Interestingly a large genetic study that included over 20 individuals from Bama concluded that by 200 BCE the people of currently inhabiting Demon Pagong already had a component of Mainland Southeast Asia DNA in their genomes (Hudjashov et al 2017).

It is possible that one such later journey is echoed in one of the long Lamaholot narrative stories known as opak. Dana Rappoport has documented various examples that were sung both during and while walking to ceremonial rituals on Tanjung Bunga (2016, 164-192). They recall journeys associated with the introduction of rice or the origin of the founding ancestors of important clans. They often include the names of places on the journey, allowing it to be mapped. Opak moran laran Nogo Ema’ is set around the origin of rice and journey of Nogo Ema’, a rice maiden. It is a long complex mythical story that begins at tana léla, the location of her grandparents on the border between the Sikka and the Lio. When her family was threatened by famine, Nogo Ema’ ordered her seven brothers to kill her so that her body could transform into rice and other vegetables to feed them. She subsequently reappeared in various forms, travelling eastwards to Tanjung Bunga, passing through Lewokluok and Lewohala on the way.

Local Lamaholot narratives describe a later influx of Lamaholot-speakers from a place called Kroko Puken – the twin islands of Lepan and Batan located beyond the eastern tip of Lembata. It seems that Kroko Puken was struck by a catastrophic natural disaster, possibly a tsunami. Ataladjar concludes that the disaster that befell Lepan Batan must have occurred between 1522 and 1525 because people from those islets were already present in Larantuka when Sira Napang became king in 1525 (Ataladjar 2015, 37).

In 1929 Ernst Vatter was told by an informant in Bama that some of the local clans originated from Sina Jawa (including the leading clan of Kabelen and Lewolein) while others, such as Beribe, originated from Kroko Puken (Vatter 1932, 141). The founding ancestor of suku Kabelen had apparently arrived in the Demon Pagong region fourteen generations previously. Allowing 25 years per generation, this would date that event to around 1550, around the time when the first Portuguese Dominicans settled on Solor.

Local Demon Pagong villagers believe that their original kampong was Lewoklouk, a defensible highland location. The kampongs of Blepanawa and Bama were established later by family groups who, for reasons unknown, decided to leave and settle elsewhere. The date of this separation is unknown but as we will see below, must have occurred prior to 1617. Clearly the attraction of Bama must have been as its coastal position, access to Mulawato Bay and closeness to Larantuka.

Return to Top

Early Colonial History

Being on the main coastal route into Larantuka it is possible that Christianity was first introduced to the Demon Pagong region as early as the beginning of the seventeenth century. At that time, Catholicism had spread from the Portuguese Dominican Mission, first established on Solor Island in 1561 to a few kampongs on the opposite eastern coast of East Flores (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 81). During the the leadership of Friar da Costa from 1562 to his death in 1590, the Solor Mission opened eight mission stations on Flores Island, some around Larantuka (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 75).

A 1617 report by a later leader of the Solor Mission, Friar João das Chagas, supported by the writings of Antonio da Sá, suggest that Catholics were not only present in Larantuka at this time but also slightly further west in Waibalun and Mulawato, Mulawato Bay being adjacent to Bama. This suggests that kampong Bama may have already been established by this date.

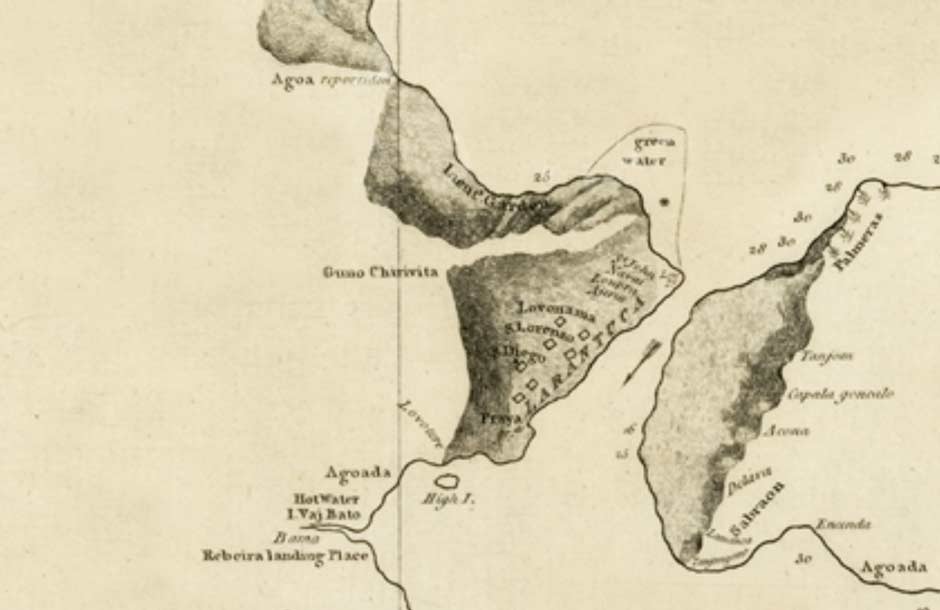

Kampong Bama was definitely in existence in 1781. In about 1792 Alexander Dalrymple, the cartographer of the English East India Company, copied a 1781 Portuguese navigation chart of East Flores and Solor Island, which marked the hamlet of Bama and an adjacent landing place along with the much larger town of Larantuka and its tiny southern offshore islet of Waibalun. To aid navigation the chart incorporated a profile of the coastal landscape projected onto the shoreline. Ilé Mandiri is clearly visible.

Kampong Bama marked on a map of East Flores and Larantuka from 1781.

Chart of the Strait of Solor, Alexander Dalrymple, London, ca. 1792.

National Maritime Museum, London.

Unfortunately nineteenth century colonial reports about the region are extremely scarce. Most colonial travellers reached Larantuka by sea although a few crossed overland from Hading Bay via Lewohala.

In 1875, E. F. Kleian, the civiel gezaghebber of Solor Island, and his posthouder Ehrich, embarked on an adventurous trek across East Flores and Sikka, one that he was advised against by both the Raja of Larantuka Don Gaspar and by the local Pastor Metz. Armed with hand pistols and flintlock guns they set off westwards from Larantuka with seven porters. From Oka Bay they walked north to Lewotalo and then Leworahang on the north coast facing Hading Bay, before turning southwest to cross the highland region of Ilé Leroboleng to reach the south coast. After a difficult ascent they arrived in the high villages of Lewero and Tuakepa located in present day Demon Pagong. Other nearby highland kampongs included Lewolaga, Leworingu and Lomika.

After entering Lewero they were immediately surrounded by curious villagers, who had never seen a European before. Kleian considered the kampong and its houses were quite clean, more so than those they had visited previously. It had three chiefs, one of whom prepared a meal of rice and roast chicken for his Dutch guests, while Kleian shared some of his brandy in return. By contrast Tuakepa, a little further on, was composed of 25 dilapidated houses.

In January 1889 the geologist Professor Carl Ernst Arthur Wichmann surveyed Flores Island from west to east, having been sent to the region by the Royal Dutch Geological Society to verify rumours of rich deposits of tin. He crossed East Flores with his porters just east of present day Demon Pagong, departing from a deserted beach in Hading Bay and ascending the valley between Gunung Delang and Ilé Padung before rapidly descending to kampong Lewotala and eventually Oka Bay. He reported that the houses in Lewotala had roofs sloping down to just one metre above the ground and had either no sidewalls at all or just bamboo sticks intertwined like a lattice (Wichmann 1891, 252).

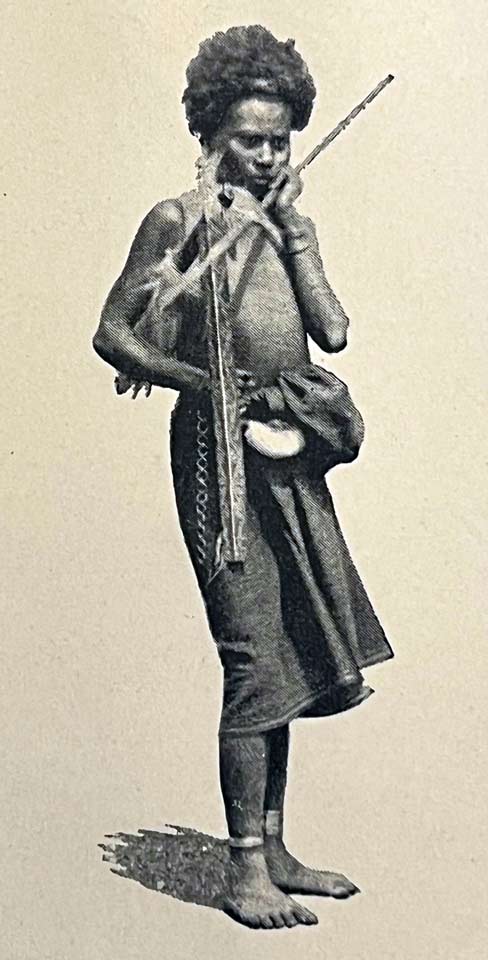

On 3 May 1881 Herman ten Kate left Maumere on a local prahu to explore Pulau Besar (then known as Great Bastard). From there he sailed eastwards along the north coast of East Flores, passing Cape Wato Wolan (Watomulan?) near kampong Wailamu in present day Titehena. He landed first at kampong Lato and then sailed further east along the north shore of present day Demon Pagong to reach kampong Hading in Hading Bay. From Hading his crew walked to Lewotala to obtain porters and the group set off overland to Larantuka. Like Wichmann, his group passed through Lewotala where he was greeted by the local raja and surrounded by local villagers and boys. He described the people as closely resembling those from Manggarai or Sikka Krowé, although many are noticeably brighter in complexion (Ten Kate 1894, 234). He added that there were ‘some alterations in dress and finery’ and provided an illustration of a local man. His appearance will have been almost identical to that of his neighbours in Lewokuok and Bama:

A ‘Solorese’ man from kampong Lewohala in 1891

From Herman ten Kate 1894

After 1881 Dutch Catholic priests had began arriving in Flores in their hundreds, some establishing bases in Larantuka, Konga and Wureh (Daus 1989, 57). By 1885 some of these priests from Larantuka had begun to visit the so-called mountain people in the kampongs of Baipito (Kennedy 1953, 191). It is likely that some attempted to convert the more accessible mountain people of Demon Pagong.

In 1887 the 27-year-old Don Lorenzo Diaz Vieira Godinho had been installed as the Raja of Larantuka. He was a committed Catholic and had an authoritarian uncompromising outlook. He soon began to irritate the Dutch officials, governing the local people in a harsh and irrational manner while becoming involved in territorial disputes with the Catholic Raja of Sikka and the Muslim Raja of Adonara (Steenbrink 2002a, 95).

Unfortunately for him, Dutch attitudes to local leaders were changing fast. When Frits Anton Heckler took over as the new Resident of Timor in Kupang in April 1902, he soon began to loose patience with Don Lorenzo. On 1 July 1904 Heckler arrived in the port of Larantuka on board the government steamship Pelikaan and ordered the troublesome Raja Lorenzo to join him, whereupon he was arrested and deposed. After being sent as a prisoner to Kupang he was exiled to Yogyakarta and temporarily replaced by the puppet, Raja Louis Blantra de Rosari.

In March 1905 Resident Heckler was superseded by J. F. A. de Rooy, who had been issued with clear instructions regarding this much more active policy. His main task was: To establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the implication of a new strategy towards the self-ruling districts, which are the majority of the whole area. The former policy of non-intervention, suggesting that the supreme authority was with the native rulers and not with the colonial authority, should be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70).

The newly installed Raja Louis de Rosari demanded that the mountain villages acknowledge his authority by bringing tribute to Larantuka. Displeased by the removal of Raja Don Lorenzo, the chiefs of Lewokluok refused and responded with insults (Kopong 1983, 70). The raja responded by imposing a fine on the kampong of 20 elephant tusks. When the raja’s assistant Ratu Openg visited Lewokluok to collect the fine the village chief, Kewisa Koten, refused to hand over any tusks, explaining that the fine was too high. When Ratu Openg returned to Larantuka with the news, Raja Louis summoned his Customary Council and decided to attack the village.

The Dutch response to the rebellion against the new Raja led to what became known as the 1905 Mulawato War (Koehuan 1982, 72-76). In support of the raja, the Dutch sent a gunship and troops from Kupang to Mulawato Bay close to Bama (Kopong 1983, 72). As they came ashore they were engaged on the beach by warriors from Lewokluok led by Igo Reang. However his fighters were no match for the well-armed Dutch troops who forced them to retreat back to their kampong. When the Dutch reached Lewokluok they burnt the villager’s houses along with their stores of rice and corn, forcing many to flee into the surrounding forest where they were eventually found by the Dutch. Many villagers were killed and injured during the attack including the clan leader Naya Leyin.

The Dutch troops then ordered the village traditional leaders to collect their elephant tusks. The total number collected was 17 tusks, which were then despatched to the Raja of Larantuka. The village head Kewisa Koten was arrested along with the clan leaders Kuda Beda and Subang Leyin and the war chief Igo Reang. After being brought to Timor Island, Igo Reang, Kuda Beda and Subang Leyin were imprisoned in Kupang for 5 years. Meanwhile, the Kewisa Koten as the customary chief was exiled for 17 years to the Dutch penal colony on Kambangan Island, located off the Cilacap coast in central Java (Kopong 1983, 79). As a final punishment the korke temple was relocated from Lewokluok to more accessible Bama (Kopong 1983, 72).

Beginning in 1908 the Hydrographic Department of the Dutch Naval Ministry began a detailed survey of the coastlines of the Lesser Sunda Islands, completing those of the Larantuka and Flores Straits in 1911. Bama is not marked, the only feature shown being Batu Kowi, a small rock promontory just to the north of the kampong.

The coastline and mountains of Demon Pagong marked on the hydrographical chart produced by the Hydrographic Department of the Naval Ministry, The Hague, June 1911. Image courtesy of the American Geographical Society Library.

In 1908 work began on the construction of the trans-Flores highway that would link Larantuka to Reo, a challenging and ambitious project that would take almost two decades to complete. The route would pass around the coast of Oka and Mulawato Bays in the southern part of present day Demon Pagong.

The Dutch looked to the Raja of Larantuka and his kapitans to impose taxes on the village kakangs and requisition corveé labour to construct roads. Not surprisingly villagers strongly opposed these measures, sometimes violently, and the Dutch responded with military force (Dietrich 1985). When the authorities imposed forced labour on the nearby village of Leworok in 1914, their leader, Kuda Duru, led a rebellion against the Dutch during which one Dutch officer was shot. It was only with great difficulty that the Dutch finally succeeded in quelling the resistance throughout East Flores (Kopong 1983, 62-107).

Return to Top

Demon Pagong in 1915-1919

At some stage during the period 1915 to 1919, Bama and some of its neighbouring kampongs was visited by the Dutch civil engineer Charles Constant François Marie Le Roux.

In 1915 the Burgerlijke Openbare Werken (Department of Civil Public Works) of the Netherlands East Indies had appointed the civil engineer Charles Le Roux to oversee the ambitious ‘Flores Way’ trans-Flores road project, a fortunate choice. Initial construction had begun in 1908. In addition to his demanding job, during his four years on the island Le Roux used the opportunity to photograph the locations and villages along the route and the local people’s daily life, increasingly becoming interested in ethnography rather than road construction.

Constructing the Flores Way through the rocky volcanic landscape near Bama.

Photographed by Charles Le Roux between 1915-1919.

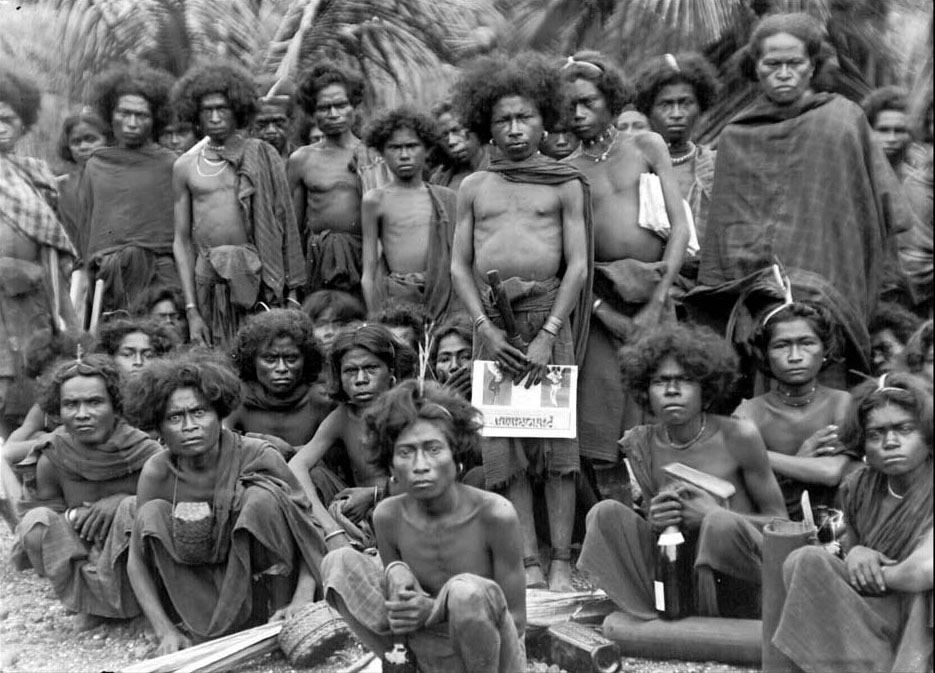

Although he did not specifically photograph kampong Bama he did photograph some local men, all of whom had strong Melanesian features. In the image below, many appear to be wearing very worn, locally woven hip wrappers, although two are wearing imported chequered cotton. Many have necklaces and their long hair tied back with strips of palm leaf. Amusingly, two men are clutching bottles of European wine while another has a copy of the Dutch popular illustrated magazine Panorama, which only appeared for the first time in 1913.

A group of men from Bama and Wolo. Photographed by Charles Le Roux between 1915-1919.

He also photographed several groups of women in some of the nearby villages, the first just to the west of Demon Pagong.

Above: Women and girls at kampong Wairunu on the Trans-Flores Highway just to the west of Wolo. Below: Young men at Wairunu. Photographed by Charles LeRoux between 1915-1919.

Women and children with hollowed out gourds for collecting water in an unknown village on the Flores Way in East Flores, photographed by Charles le Roux at some time after 1915

All the women appear to be poor, enduring tough living conditions and being forced to collect fresh water from local streams and springs. They were all wearing local hand-woven sarongs, decorated with narrow warp stripes, some ikatted. The sarongs were mostly tied above the breasts and worn with necklaces and sometimes ankle bracelets.

Return to Top

Demon Pagong in 1929

The German ethnographer and collector Ernst Vatter visited Bama during his tour of eastern Indonesia in search of items for the Museum Museum für Volkerkunde in Frankfurt. He and his wife Hanna had arrived at the port of Larantuka on 9 November 1928 on board an old Dutch steamship, the KPM De Clerq, which had departed from Surabaya nine days previously. He initially spent three weeks in kampong Lewoloba, one of a string of kampongs known as Baipito (see Ilé µandiri webpage) spread out along the northern foot of Ilé Mandiri, before exploring Tanjung Bunga.

At the beginning of January 1929 Ernst Vatter set off from Larantuka with the Catholic priest Father Strieter in a small motorboat. After travelling for several hours across Oka Bay, they landed on the beach close to Bama (Vatter 1932, 139-142). He had left his wife, Hanna Vatter, back in Larantuka because just before Christmas she had contracted malaria. Although Vatter’s journal includes only a few paragraphs on this region, it does give us a glimpse of what life was like at that time.

Vatter and his companion landed on the beach to be greeted by a crowd of children with a few local men. Vatter noted the residents of Bama were immediately recognizable by their hairstyle – their long, woolly hair laid flat back and tied down over the top of ther heads with a thin cord.

The settlement of Bama was not far from the beach. Vatter clearly misunderstood the local geography. He wrote that there were actually two kampongs – Lēkluo (Lewokluok) and Blepanama – but they completely merged to form one large, closed village. Apparently in Larantuka they were all labelled as Barma, a grouping that encompassed the entire coastal area of this part of Oka Bay.

Two men with strong Melanesian features and woven hats at Bama, one with a basket for sirih pinang, the other with a parang and chequered imported cotton hip wrapper. Ernst Vatter 1929.

The design of the houses and the layout of the village showed only minor differences to those previously seen in Lewoloba and the other Baipito kampongs behind Ilé Mandiri. Just like today, the streetscape revealed the proximity of the sea. Unlike today it illutrated the economic importance of fishing at that time, with long rows of fish, cuttlefish and other sea animals hung out to dry like laundry on long bamboo poles across the village streets, giving off a terrible smell. The village had several much smaller houses built on stilts known as basal. These were the houses for the bachelors of the individual clans, inhabited by young men who had reached maturity and were no longer allowed to sleep in the house of their parents.

Vatter met with some of the village chiefs in Bama. The eldest with snow-white hair was Nabu, who had once been a great war chief. He wore a plaited cap, as did the other village elders. Another slightly younger chief was Bolong who had his hair tied into a little topknot at the back of his head.

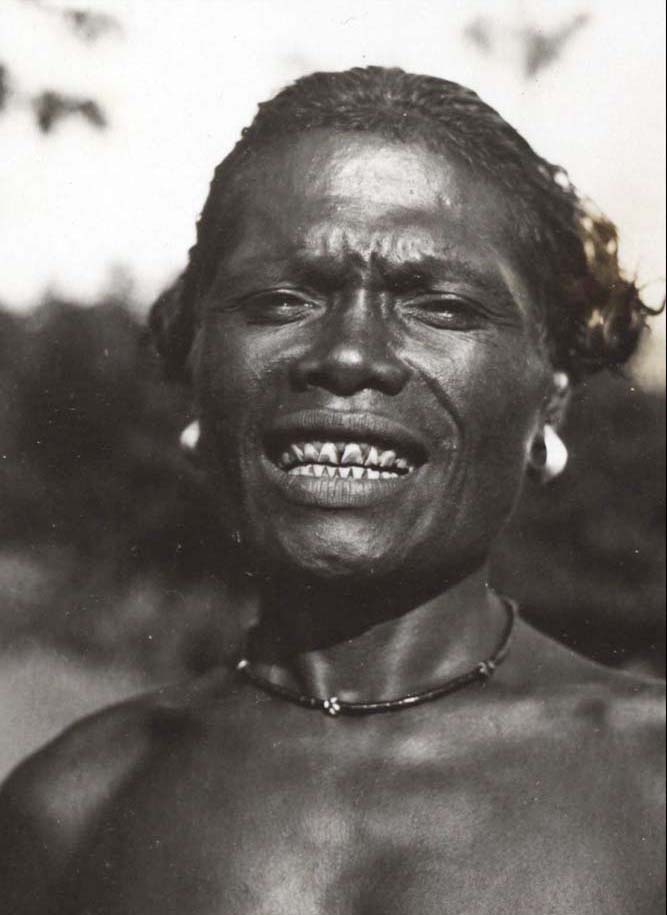

Nabu, the most elderly chief of Bama. His black and white dotted pearl necklace was a symbol of his status

Although much younger and not a chief, Homé Kebelen was a distinguished man who belonged to the Lamoiang clan of suku Kebelen, the highest status clan in Bama. He was the important head of the village youth, well respected by the elder chiefs, and both intelligent and forthright in his views. Vatter described him as the head of the jeunesse dorée (fashionable young people) of Bama. His photographic portrait shows him with his hair brushed back and tied to his head with a thin cord, his teeth ground smooth and notched and wearing earrings and a necklace.

Homé Kebelen, the youth leader of Bama

Vatter raised the subject of war and warfare. Homé explained that in the past, when warriors from one village conquered an enemy village, all of the men, including old men and boys, were killed. This even included babies in the arms of their mothers if they were male. However there was an unwritten rule that women of all ages were inviolable. Warriors who were killed during a war were not buried but laid out on a two-meter-high platform in the forest.

In the evening Vatter walked through the village cemetry to the shore. The cemetry was barely recognisable and uncared for. The villagers had told him that it was not very old and that their grandfathers were buried there. Every grave had been damaged, the stone mounds over the gravess broken and their contents ransacked by pigs. Human skulls and individual bones lay everywhere. Vatter must have seen this as a major collecting opportunity. Unbeknown to the villagers he surreptitiously and unethically collected the skulls of ten of their ancestors to take back home for analysis. He could not locate any lower jawbones.

After Vatter’s return to Germany the skulls were sent to the Institute for Physical Anthropology in Frankfurt for measurement by the physical anthropologist H. W. Müller. He found the skulls to be small and strongly brachycephalic (flat at the back) and classified them as negrito (a crude description referring to a small dark-skinned person), similar to the Semang people of Malaysia or the inhabitants of the Andaman Islands. It seems that he and his colleagues had not studied Melanesian anthropology so were unable to calssigfy them as such.

After staying overnight in Bama, horses that had been sent from Larantuka arrived in Bama the following morn and Vatter set off on horseback with Father Strieter southwards for Nobo on the south side of Konga Bay.

Return to Top

Demon Pagong in 1950

The Yale anthropologist Professor Raymond Kennedy travelled by jeep from Ende to Larantuka via Maumere on 20 December 1949. He stayed for a few days and then returned two further times during January 1950. Unfortunately he conducted all of his anthropological field studies within the kampongs of Baipito, especially in Lewohala and Wailolong. Despite the fact he must have driven past Bama on six occasions, he left us with no information about it.

An anonymous image of a group of men at Lewokluok, dated 1948

Return to Top

Ethnography

The people of East Flores are ethnically Lamaholot and speak one of the 35 Lamaholot dialects that were first identified by Gregorius Keraf in 1978. Prior to 1945 the local people were referred to as the Solorese, although they call themselves the ata kiwan, the people of the interior. The term Lamaholot is recent, having only been adopted by foreign anthropologists and linguists in recent times.

The dialect spoken in Demon Pagong differs from those spoken in Tanjung Bunga, Ilé Mandiri, Léwoléma, Titehena or Lewotobi (Keraf 1978). Keraf termed it the Bama dialect, and classified it as one of the ten spoken on mainland East Flores and one of the twenty-three classified as western Lamaholot (Akoli 2010, 18).

The Lamaholot have long been divided into two antagonistic groups, the Demon and the Paji – the Demon being the inland ata kiwan, swidden agriculturalists with pagan beliefs who were subject to the Raja of Larantuka while the Paji were later arrivals, coastal Muslims dependant on fishing who were subject to the Raja of Adonara. The entire population of Demon Pagong are Catholic and fall into the Demon category.

Each village in Demon Pagong is socially divided into patrilineal clans called suku, each one of which has a legend about its founding ancestor, along with a ritual leader and a ritual speaker. The three indigenous clans are Kabelen, Beribe and Nedabang, of which Kabelen is the most senior. Lower status clans include Lewolein or Lein, Lewogoran or Goran, Kumanireng, Lewohera, Lewati, Lubur and Uo Matan. One wonders if the Kabelen clan was named after the local mount of Ilé Kawalelo, which Vatter transliterated in 1929 as Kabalelo (1932, 140). He was told that it was on this mountain that the founding ancestor of that clan, Patji Tadon Doron Buan, established the region’s first korke temple.

One important element of Lamaholot culture is the traditional system of leadership, where each village was governed by four ritual leaders (Vatter 1932, 81):

- the kepala Koten was the most senior of the four leaders being in control of internal village affairs including land ownership (koten means head),

- the kepala Kelen was responsible for external affairs, dealing with neighbouring villages and in the past dealing with the Dutch authorities (kelen is the hind leg of an animal),

- the kepala Hurit and the kepala Marang were advisors and mediators if there was a disagreement between the heads of Koten and Kelen (hurit means to sacrifice an animal, marang means to speak or pray).

Other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders became too powerful. Since independence and the introduction of democratic regional and village government in the early 1960s, their roles have been superseded by an elected kepala desa.

Today the four ritual leaders still play an important role during the ritual sacrifice of goats and pigs. The kepala Koten holds the animal’s head, the kepala Kelen holds the back legs, the kepala Hurit wields the knife while the kepala Marang is responsible for chanting ritual prayers. The animal’s blood is then spread on the village’s sacred nuba nara stone.

Many writers mistakenly interpret the four positions of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang as representing village sukus, but the latter are completely different. Traditionally the leaders from four specific village sukus will have been assigned to the roles of head of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang. These will be different for every village. However in some villages the less important positions of Hurit and Marang are not represented.

In 1929 Ernst Vatter discovered that in Bama the Lamoiang lineage of suku Kabelen was divided into two parts, one of which fulfiled the role of suku Koten, the other that of suku Kelen. Suku Lewolein and suku Beribe performed the roles of suku Marang and suku Hurit respectively (Vatter 1932, 141).

In the past marriage between clans was governed by strict rules. Vatter considered those in nearby Lewohala at Ilé Mandiri to be very complicated and far from uniform (1932, 75). While they certainly were complicated for some villages, they did align with the system of asymmetric alliance. This is conceptually a circular process in which marriages are cycled in one direction through a chain of patrilineal groups. Ouwenhand (1950, 56-57) put forward a grossly simplified model of this process where young women were exchanged as follows:

Koten → Hurit → Kelen → Koten

Even today, marriage always demands a special gift exchange between the lineages forming the alliance: thus bridewealth composed of one or more elephant tusks (bala) is given to the woman’s lineage, while in return a counter-prestation composed of ceremonial cloths is given to the man’s lineage. In modern times, tusks are less easy to obtain and are often substituted by cash and livestock.

The ritual life of southern Demon Pagong revolves around the sacred village temple, known as the koke bale, located in Lewokluok. This is shared with the villages of Blepanama and Bama.

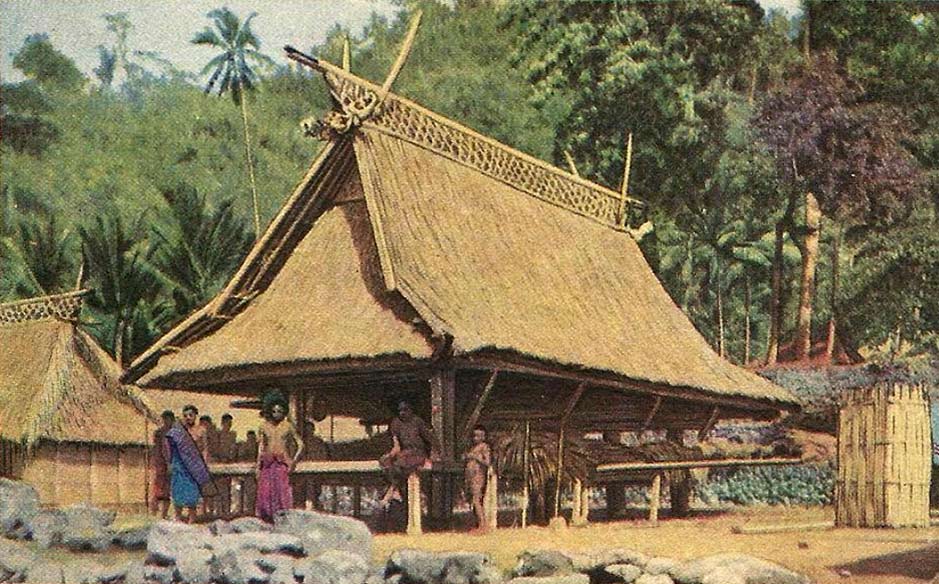

We have already mentioned that after the Dutch destroyed the temple at Lewokluok in 1905 it was relocated to Bama. At some unknown stage later it was rebuilt. There is no record of the appearance of the traditional temple, although we do have a couple of illustrations of structures in East Flores dating from the 1930s. Bernard Andreas Gregorius Vroklage SVD made the first during his ethnological and anthropological tour of Flores in 1936.

Above: sketch of a ‘spirit house’ in East Flores, B. A. G. Vroklage 1936. Below: another illustration of a village temple in East Flores from the 1930s.

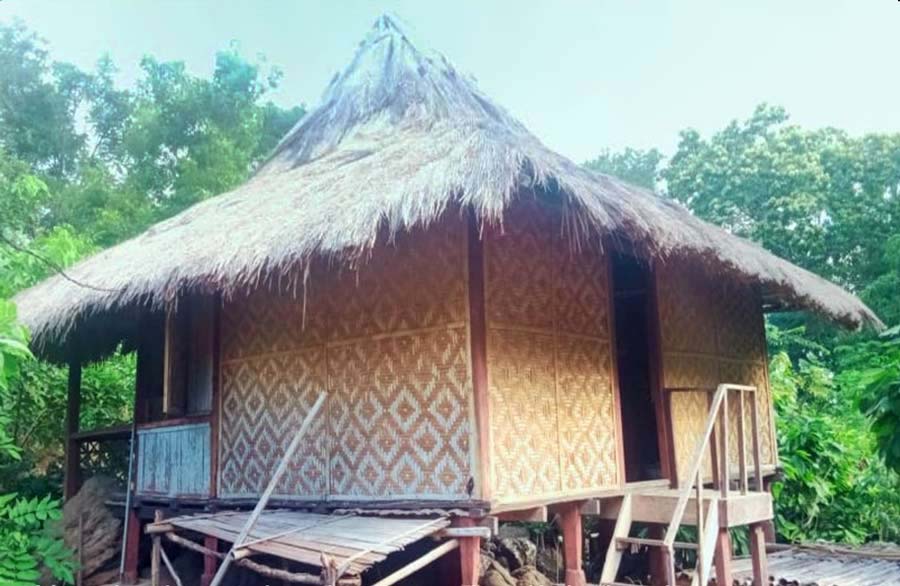

The current village temple at Lewokluok was rebuilt in 2014 on a shaded terrace in the centre of the kampong. Its thatched roof is supported by six main pillars representing the six main Demon Pagong clans. These are surrounded by eighteen painted supporting pillars that represent all of the Demon Pagong clans, decorated with rows of motifs associated with each of them (Indrayani 2017).

Above: the clan house at Lewokluok, built in 2014. Below: showing the interior and supporting pillars along with ceremonial gongs.

Several clan houses owned by the most important clans surround the koke bale. These are used by the clan leaders for meetings and for storing clan property such as elephant tusks, gongs and textiles.

The modern clan house of suku Beribe at Lewokluok

The korke bale has two adjacent flat arenas, the innermost, known as the naming, being the highest, largest and most sacred, the outermost, known as the nama, surrounded by a perimeter of flat stones and containing the sacred nuba nara stones that symbolise the founding ancestors. One is flat, serving as a seat for the clan elders during ceremonies, while the other is vertical.

It is in the namang arena that the clan leaders conduct most traditional ceremonies, the majority revolving around the annual agricultural cycle, starting with Tena Prat, the ritual held before clearing the land for cultivation and finishing with the Goleng Lewo harvest festival.

The final phase of rituals opens with the Belo Howok ceremony, involving the sacrifice of male goats and pigs. Led by the Kabelen clan, the animals are decapitated by parang and the bodies are hung on bamboo sticks overnight to be cooked and eaten the following day.

Decapitating a goat at the belo howok ritual in Lewokluok in 2016

Image courtesy of Cendana News

Belo Holok is immediately followed by the Toto Dulat ritual, in which all the participants gather around the koke bale to have their foreheads marked with chewed betel nut and candlenut paste. Finally in the Hudu Bakat ritual the leaders of the Kabelen, Lein and Beribe clans are presented with three cones of rice, each prepared by women from the same three clans. The leader of Kabelen then feeds the Lein clan, the Lein clan feed the Beribe clan and the Beribe clan feed the Kabelen and Goran clans.

The sacrificed animals are guarded overnight for the big Goleng Lewo feast the following day. While the meat is cooked the women of the village prepare accompanying tumpeng festival rice dishes. That evening the food is served to all the festival participants to the accompaniment of ritual chanting.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Aritonang, Jan S., and Steenbrink, Karel, 2008. A History of Christianity in Indonesia, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Arndt, Paul, 1940. Soziale Verhältnisse auf Ost-Flores, Adonare und Solor, Aschendorffschen Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2021. Kecamatan Demon Pagong Dalam Angka 2021, Larantuka.

Galipaud, Jean-Christophe; Kinaston, Rebecca; Halcrow, Siân; Foster, Aimee; Harris, Nathaniel; Simanjuntak, Truman; Javelle, Jonathan; and Buckley, Hallie, 2016. The Pain Haka burial ground on Flores: Indonesian evidence for a shared Neolithic belief system in Southeast Asia, Antiquity, vol. 90, pp. 1505-1521.

Heynen, F. C., 1876. Het rijk Larantoeka op het eiland Flores in Nederlandsch Indië: studiën op godsdienstig, wetenschappelijk en letterkundig gebied, W. van Gulick, ‘s Hertogenbosch.

Indrayani, Ida Ayu Agung, 2017. Studi Teknis Rumah Adat Lewokluwok, Larantuka, Flores Timur, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Balai Pelestarian cagar Budaya Bali, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia.

Kennedy, Raymond, 1955. Field Notes on Indonesia: Flores, 1949-1950, Human Relations Area Files, Behaviour Science Monographs, New Haven.

Kleian, E. F., 1891. Eene voetreis over het oostelijk deel van het Eiland Flores, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 34, pp. 485-532.

Koehuan, M., Kotten, B. K., and Bunga, H., 1982. Sejarah perlawanan terhadap imperialisme dan kolonialisme di daerah Nusa Tenggara Timur, Departamen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional, Jakarta.

Kopong, Elias, 1983. Sejarah Perlawanan terhadap Imperialisme dan Kolonialisme di Nusa Tenggara Timur, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional, Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Müller, H. W., 1935. Die Kleinschädelformen Südasiens. Ein Beitrag zum Kleinwuchsproblem, Zeitschrift für Rasssenkunde, vol. 1, p. 53, Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart.

Pleijte, C. M., 1894. Notes on the Ethnography of Flores, Glimpses of the Eastern Archipelago: Ethnographical, Geographical and Historical, pp. 30-39, The Singapore and Straits Printing Office, Singapore. Originally published in 1890 in Ethnographische Notizen über Flores und Celebes, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, vol. 3, Leiden.

Rappoport, Dana, 2021. The long journey of the rice maiden from Li’o to Tanjung Bunga: A Lamaholot sung narrative (Flores, eastern Indonesia), Austronesian Paths and Journeys, pp. 161-192, ANU Press, Canberra.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002b. Another Race Between Islam and Christianity: The case of Flores, Southeast Indonesia, 1900-1920, Studia Islamika, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 63-106, Jakarta.

Steenbrink, Karel A., 2003. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1900, KITLV Press, Amsterdam.

Sutikna, T.; Tocheri, M. W.; Morwood, M. J.; Wahyu Saptomo, E.; Jatmiko, et al. 2016. Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia, Nature, vol. 532, pp. 366-369.

Ten Kate, Herman F. C., 1894. Groot-Bastaard – Larantoeka – Adoenara - Solor, Verslag eener Reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesië, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlansch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. xi, pp. 231-246, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Utomo, Susilo Setyo; Djakariah,Djakariah; and Tukan, Joanetta M., 2020. Perjuangan Kewisa Koten di Lewokluok Flores Timur Melawan Belanda Tahun 1905, Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan Sejarah UHO, vol. 5 , issue 1, pp. 49-56.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Viola, Maria Alice Marques, 2013. Presença histórica “portuguesa” em Larantuka (séculos XVI e XVII) e suas implicações na contemporaneidade, PhD Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon.

Wichmann, 1892. Flores, Bericht über eine im jahre 1888-89 im auftrage der Niederländischen Geographischen Gesellschaft ausgefürte reise nach dem Indischen Archipel, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlansch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. viii, pp. 188-293, Leiden.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 12 March 2022.