Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Lawo with a Complete Covering of Motifs

Lawo Butu

Men's Textiles

Luka Sarongs

Luka Shoulder Cloths

Bibliography

Weaving in Ende Regency

Historical References to Endenese and Lio Textiles

Samuel Roos 1877

Herman ten Kate 1891

Max Weber 1899-1900

Johannes Elbert 1912

Charles Le Roux 1915-1919

Bertho van Suchtelen 1921

Elisabeth Wilhelmina Viruly Verbrugge 1922

Father Simon Buis SVD 1923

Raymond Kennedy 1949-1950

Roy Hamilton 1989

Willemijn de Jong 1987-2022

Conclusions

The Nggela Weaving Community

Nggela Ecology

Local Cotton and its Preparation

Commercial Cotton and Synthetic Yarns

Warping Up and Binding

Indigo Dyeing

Morinda Dyeing

Other Natural Dyes

Synthetic Dyes

Unbinding and Starching

Assembling and Focussing

Final Starching

Weaving in Nggela

Loom Terminology

Sewing Up the Sarong

The Complete Weaving Process

Women’s Sarongs

Lawo with Centre Panels

Lawo with Vertical Bands

Lawo with Horizontal Bands

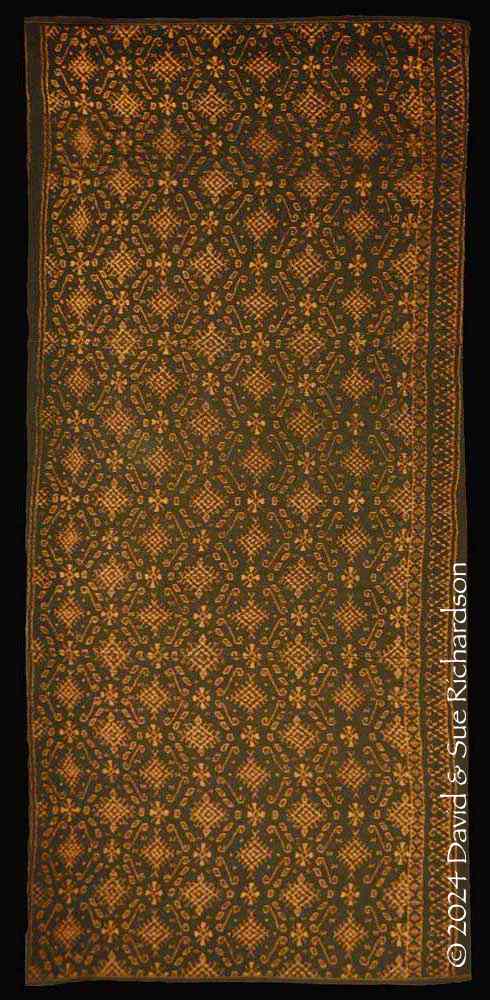

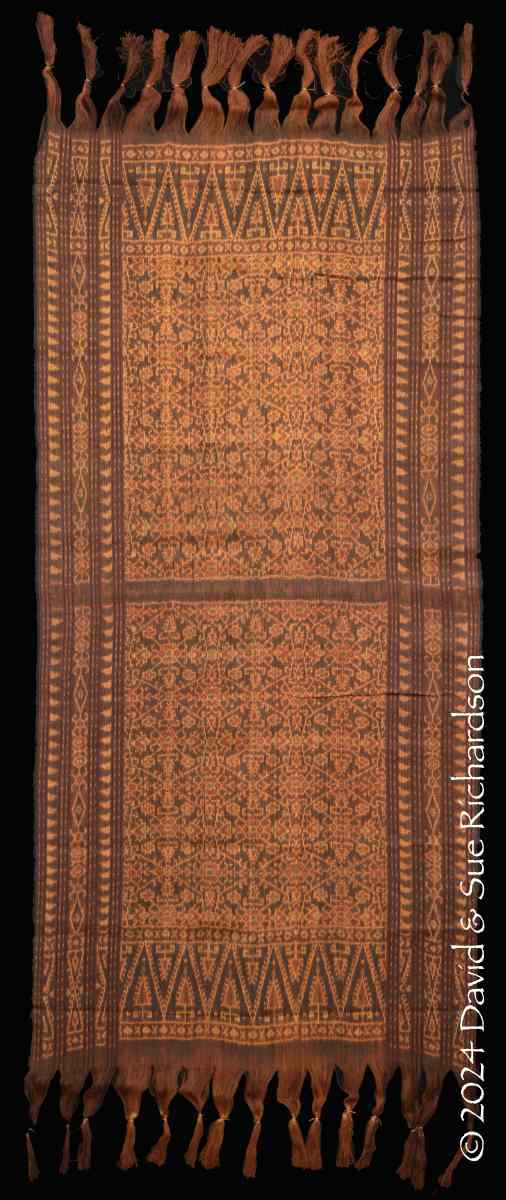

Lawo with a Complete Covering of Motifs

Lawo Gamba

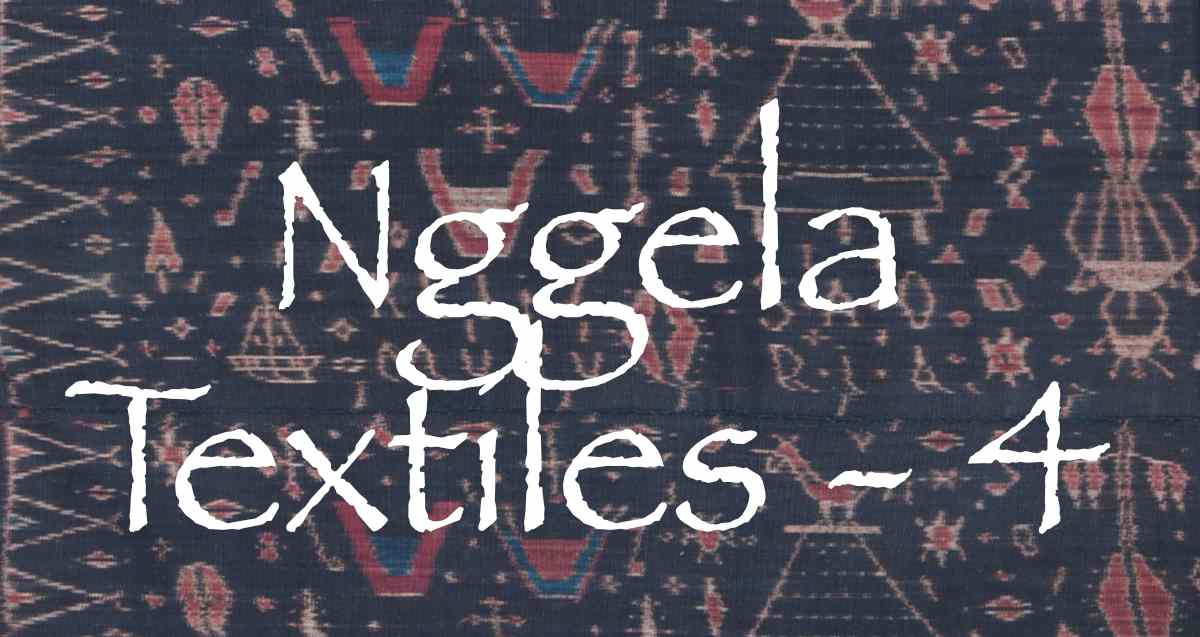

The lawo gamba has no structural layout, being completely covered in a variety of freely-arranged, naïve, pictorial motifs. The term gamba is a cognate (having the same derivation) of the Indonesian word gambar (picture), thus referring to the pictorial nature of these textiles.

Apparently during the 1930s some high-ranking weavers incorporated anthropomorphic figures and jewellery motifs into their ikat sarongs, but the first lawo gamba were not produced until the 1970s (de Jong 1994, 274, note 16). Their creation may have been motivated by their greater saleability and the need to generate cash for school fees and sustenance, especially with increasing Flores tourism (de Jong 1994, 225).

Lawo gamba can be classified into two types:

- those with motifs symbolising objects, animals or people from everyday life

- those with motifs derived from oral narratives or adat rituals, especially those depicting the rice maiden

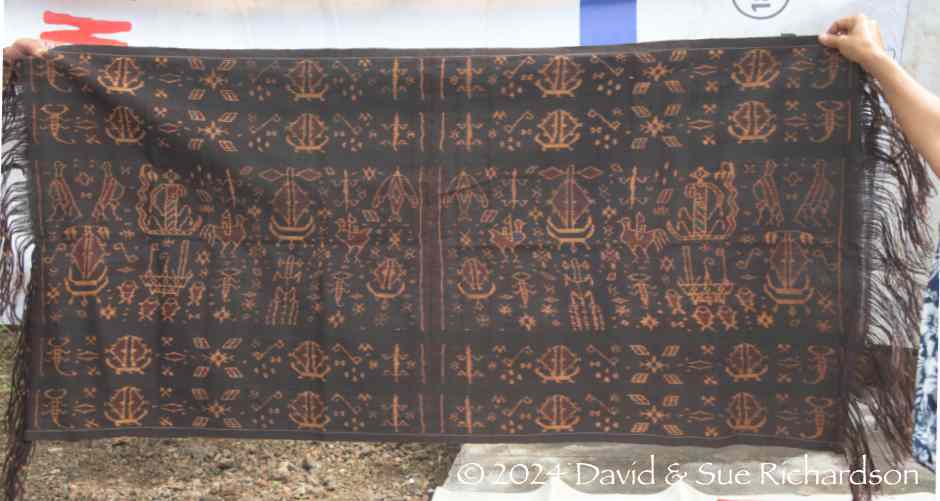

This example of the first type was made by the late Agatha Reda in about 1968. Mama Agatha belonged to the high-ranking house of Sa’o Labo, but sadly died in 2008 at the age of 70. She decorated her lawo gamba with images of the clan house Sa’o Labo topped with a duck (on the reverse side), the clan house Sa’o Ria topped with a rooster, the kangga ceremonial platform, the three-coloured crater lakes of Kéli Mutu, wea gold earrings and sailing ships.

A lawo gamba made by Agatha Reda in about 1968. Richardson Collection

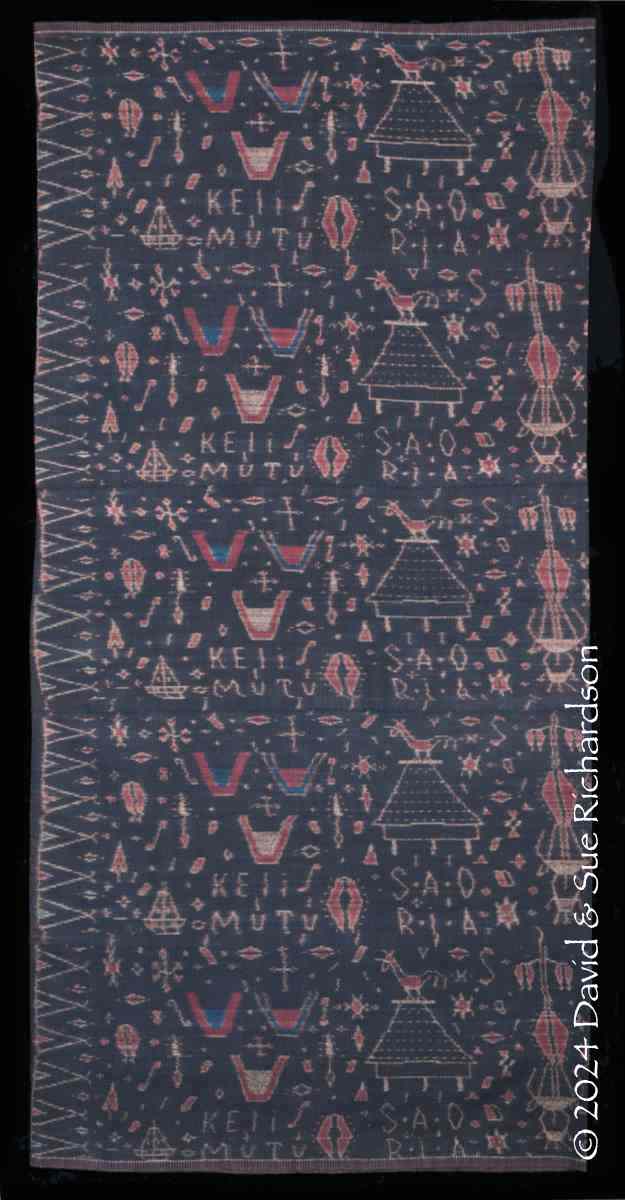

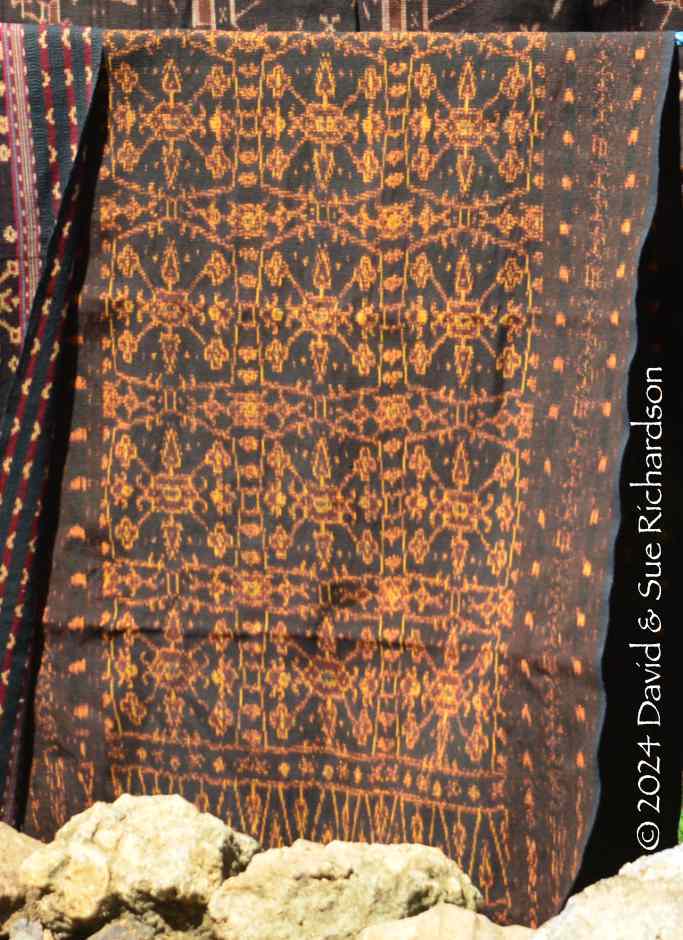

The second example was made in Nggela in 2015 by Teresia Rewo, and was naturally dyed with indigo and morinda. It is decorated with scorpions, butterflies, lizards, wea gold earrings, crescent-shaped pectoral decorations and the traditional clan house Sa’o Labo, topped with a duck.

One side of the lawo gamba made by Teresia Rewo in 2015. Richardson Collection

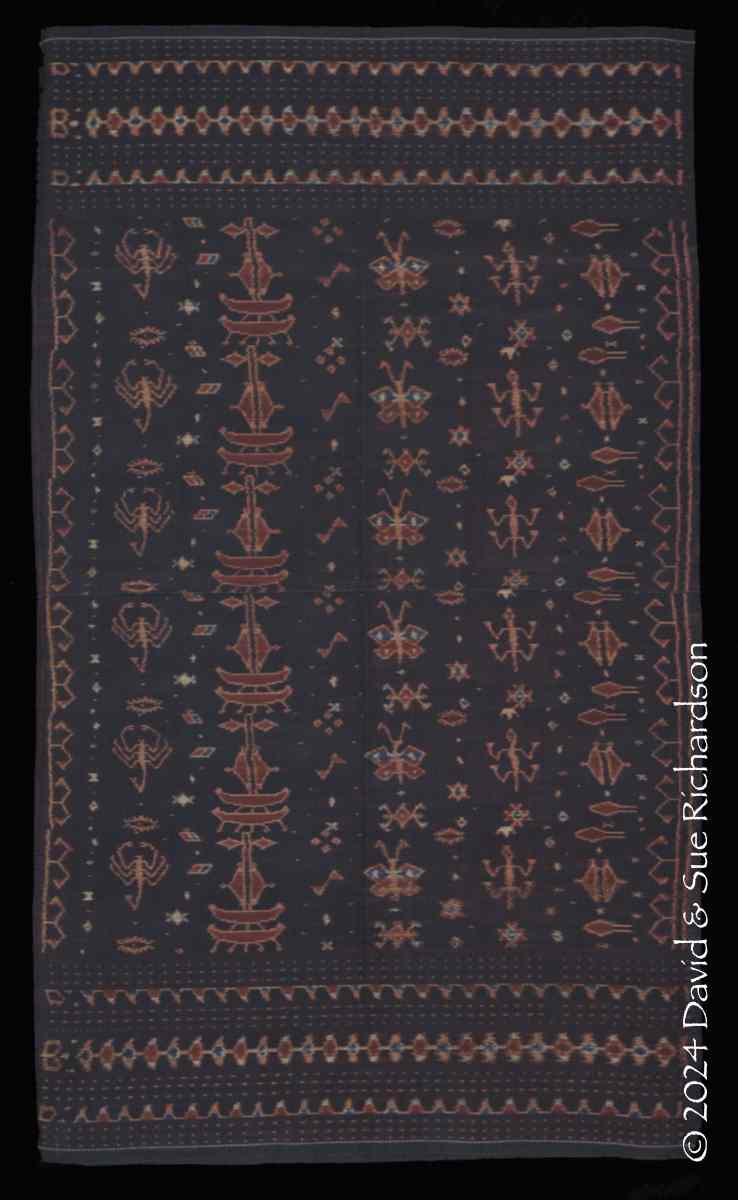

Lawo Gamba Garuda

The decoration of the lawo gamba Garuda includes a motif representing the Garuda Pancasila, the mythical Golden Eagle that is the national emblem of Indonesia and symbolises the Indonesian Day of Independence, 17 August 1945.

According to Elisabeth Pango (Mama Ango), the first weaver to bind a lawo gamba with an image of the Garuda was Yulita Gamba, known as Mama Gamba (de Jong 2020, 32). Today one of the best binders of this motif is said to be Mama Pape. Another accomplished binder who has produced several lawo gamba Garuda during the past decade is Mama Ango. In 2017 Mama Ango mentioned that the Garuda motif was difficult to bind and looked coarse if it was depicted too large. She also said that during the Suharto era, which came to an end in 1998, people were afraid to buy such sarongs (de Jong 2021).

In the example made by Mama Ango, shown below, the national eagle emblem of the Pancasila is flanked by the motif of the rice goddess along with jewellery, the tree of abundance and various animals:

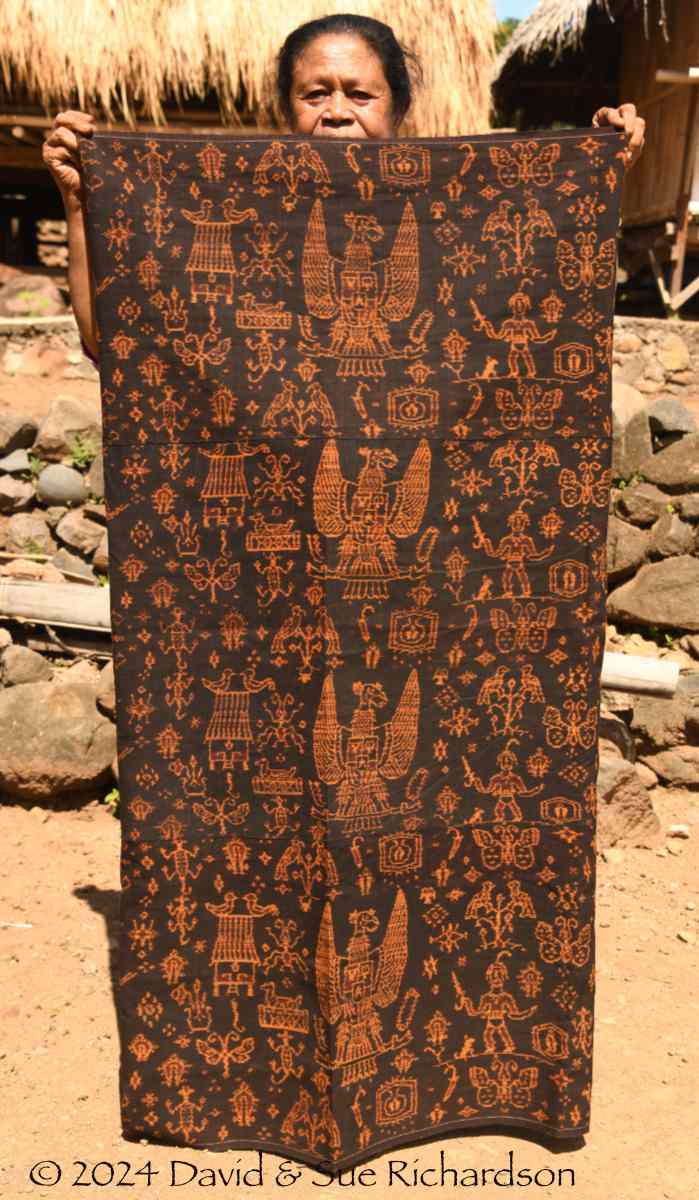

A lawo gamba Garuda made by Mama Ango

The second example below was bound by Berdina Siger and includes Sa’o Labo with ducks on the roof, birds, butterflies, gekos, jewellery and even chilli peppers:

A lawo gamba Garuda made by Berdina Siger

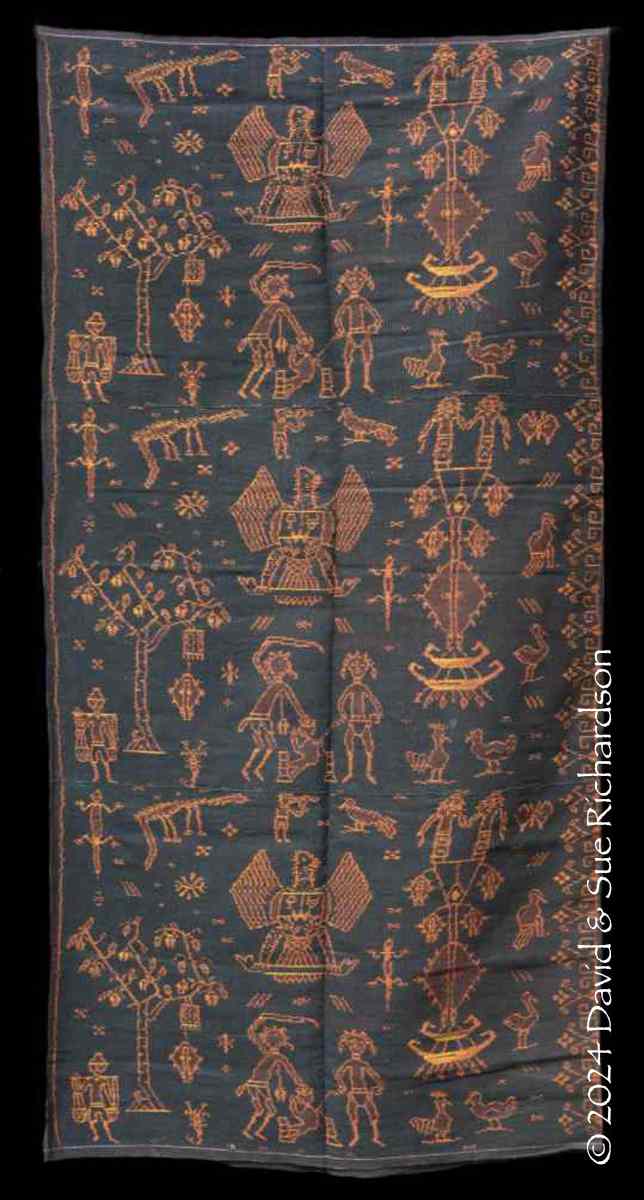

Lawo Gamba Ine Mbu Ine Pare

One dominant theme depicted in lawo gamba is the legend of the rice goddess Ine Mbu Ine Pare. Ine Mbu lived in the northern Lio region and was the daughter of Ame Ratu, the son of the ruler of Kéli Mutu, Konde Laki, and his wife Ine Kaja. She had two older brothers – Ndale and Sipi. One year the region was affected by a long dry season and the people were suffering with famine, the rice fields left empty. Ine Mbu decided to go into the jungle to pick wild fruit, but while there she accidentally cut her knee on a thorny tree. Blood dripped from her wound onto to the ground from which point paddy rice suddenly grew. She magnanimously offered to sacrifice herself so that the people could eat. The killing of Ine Mbu was done in a noble manner, with the permission of the gods and her parents. After she was beheaded by her two brothers, her body was dismembered and buried on mount Kéli Ndota. Her heart became rice, her bones became cassava, and her eyes became maize. Following the killing, Ine Mbu was reborn as Ine Pare, the Rice Mother.

It seems that in some Lio villages, this myth was played out in reality as an agricultural fertility ritual. Every year, villagers would pick a young girl to be sacrificed. One individual who was complicit in such evil acts was Pius Rasi Wangge, the Raja of Tanah Kunu Lima, the landschap that included Lisé, Mbuli, Nggela, Wolojita and Ndori. In 1940 he was put on trial in Kupang for corruption and sentenced to ten years exile in Kupang the following year (Steenbrink 2003, 109; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 243). The Japanese released him in 1942 and returned him to Flores. However, after the war the Dutch returned him to Kupang and tried him as a collaborator. He was executed in April 1947. According to Raymond Kennedy, one of Pius Rasi Wangge’s crimes was the killing of young girls for agricultural field rites (1952, 268).

Fortunately after the Second World War, this tradition was stamped out by the Catholic church and the Dutch authorities. Yet in some places it was re-enacted in a symbolic way. Dana Rappoport found that every year on Tanjung Bunga in East Flores, each landowning clan would select a fifteen-year-old girl as a ‘rice maiden’, who was then symbolically sacrificed in the rice field at the time of sowing and then again at the rice harvest in May (2011, 107). Rappoport has also reported a local narrative that describes the eastward journey of the rice maiden from the Lio-Sikka border to Tanjung Bunga, possibly echoing the early migration of some Austronesian groups into eastern Flores (2016, 164-192).

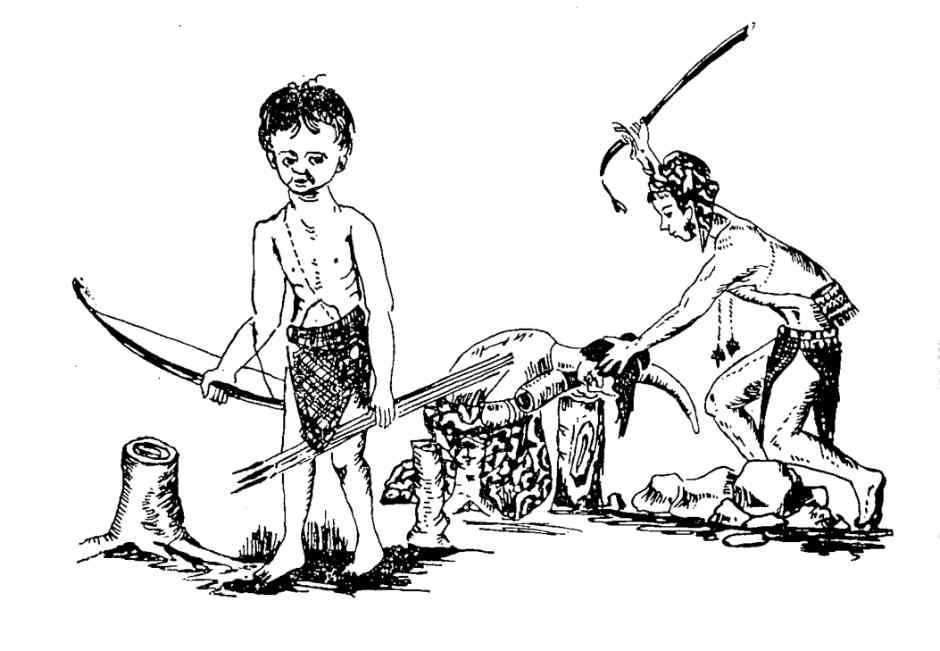

The murder of Ine Mbu by her elder brother Ndale. Before she was beheaded her neck was placed on an ivory tusk as a sign of respect. Illustrated by Sareng Orin Bao in Nusa Nipa, 1969

In 1969 the priest, anthropologist and museum director Piet Petu SVD from Sikka in Flores, also known as Sareng Orin Bao, published the book Nusa Nipa that discussed the mythical history of Flores. It included images of the killing of Ine Mbu and her resurrection as the rice goddess Ine Pare.

During the 1980s Piet Petu distributed his book to some of the weaving villages in the Lio area (de Jong 2011). In doing so he hoped that they might incorporate the ancient Flores myths in their ikat designs and improve the saleability of their lawo gamba. One weaver who was inspired by the images in the book was Mama Ango, who happened to come across some sheets of paper with images from Piet Petu's book. Another weaver who was one of the early producers of this type of lawo was Mama Rafi(de Jong 2020b, 4).

The rice goddess Ine Pare dressed in a Lio sarong decorated with a snake skin pattern, standing among the rice sprouting from her own flesh. A giant snake protects the rice plants from the walang sangit, an insect pest that attacks rice crops, while gold jewellery hangs from its jaws as a symbol of wealth.

Illustrated by Sareng Orin Bao in Nusa Nipa, 1969

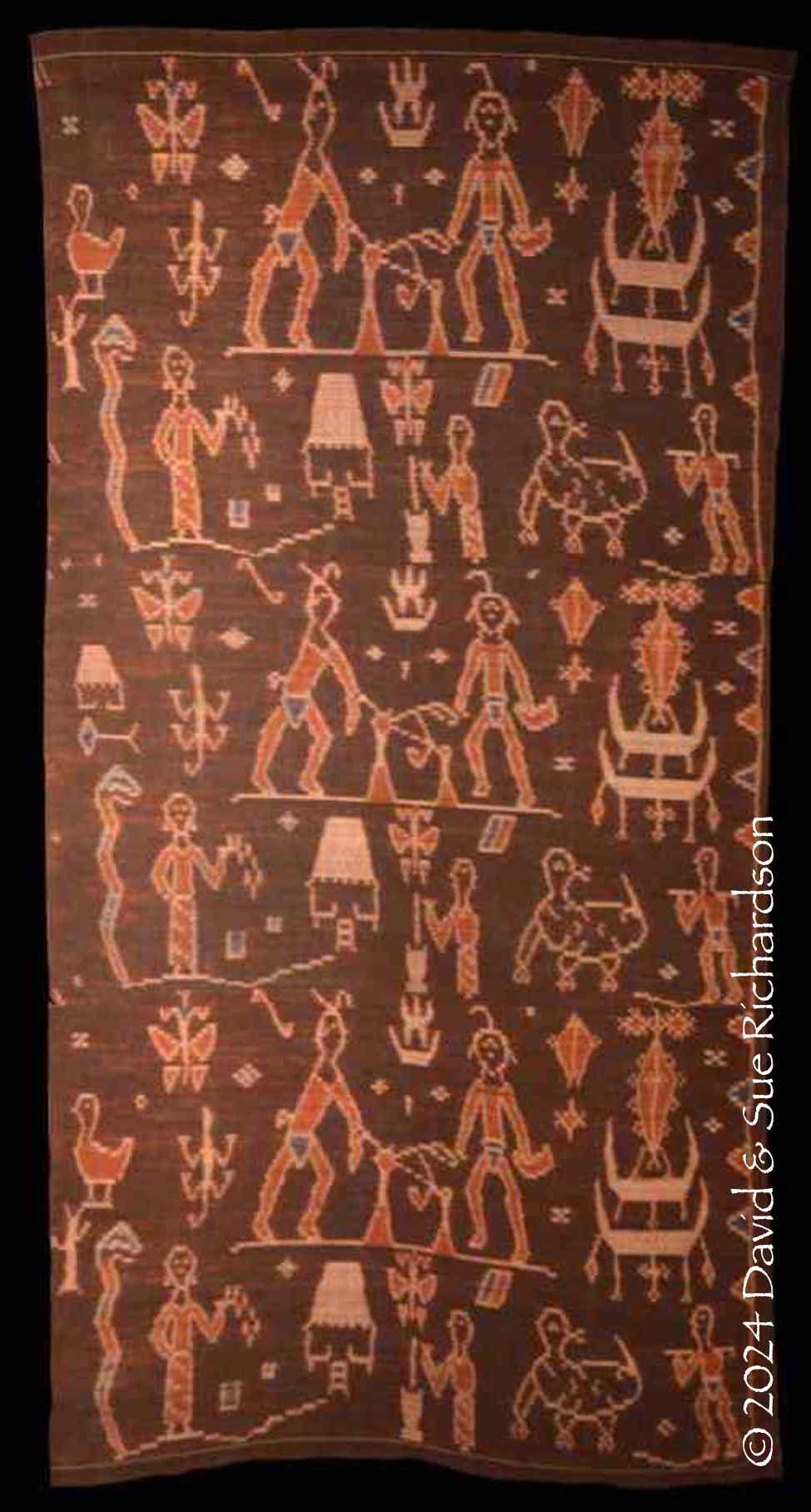

A simple, naturally dyed cotton lawo gamba, made by Anastasia Bhoa (Mama Anas) in 2014.

It depicts the Flores rice myth and the Nggela rice ritual, todo obo. De Jong Collection

Although the lawo gamba Ine Mbu Ine Pare became increasingly popular after 2000, only the most skilful Nggela ikat binders, perhaps one tenth of the total, were able to make them. One of the most able is Petronela Ji'e (Mama Pape), who made the following example with motifs based on drawings from Piet Petu's book and arranged as mirror images. One motif depicts Ine Pare standing in a rice field along with the mythical snake holding gold jewellery in its jaws:

A synthetically dyed rayon lawo gamba made by Petronela Ji'e (Mama Pape) between 1988 and 1999. De Jong Collection

Lawo gamba are not used in gift exchanges, but women do like to wear them at festivities.

Lawo Jaba Muku

The lawo jaba muku is a radically new design of lawo gamba created by Mama Ango in 2015. The whole cloth is covered with a diagonal lattice of geometrical motifs, each having a central hooked diamond framed by banana slices (jaba muku).

A synthetically dyed lawo jaba muku woven with a mixture of cotton and rayon by Elisabeth Pango in 2015. De Jong Collection.

The motif is very similar to the one created by Mama Ango for her lawo nggamba.

Return to Top

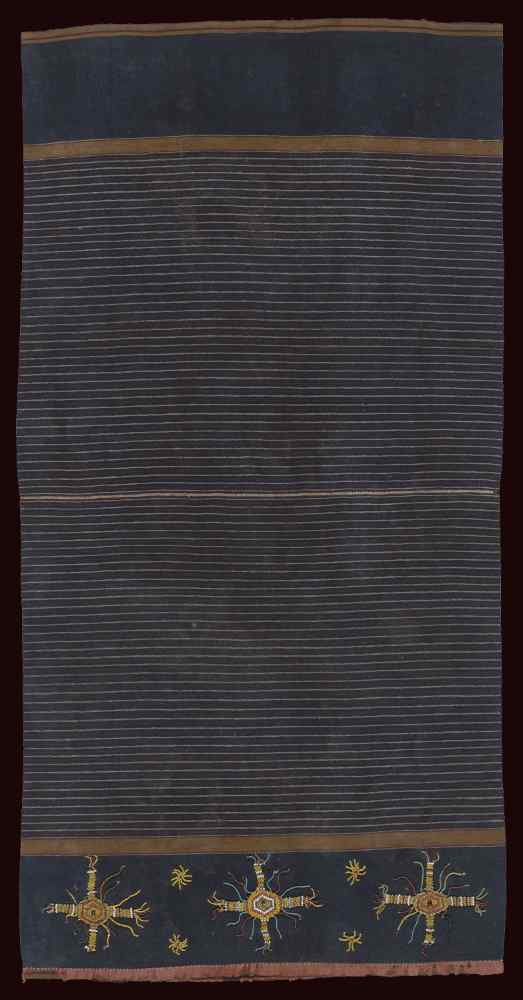

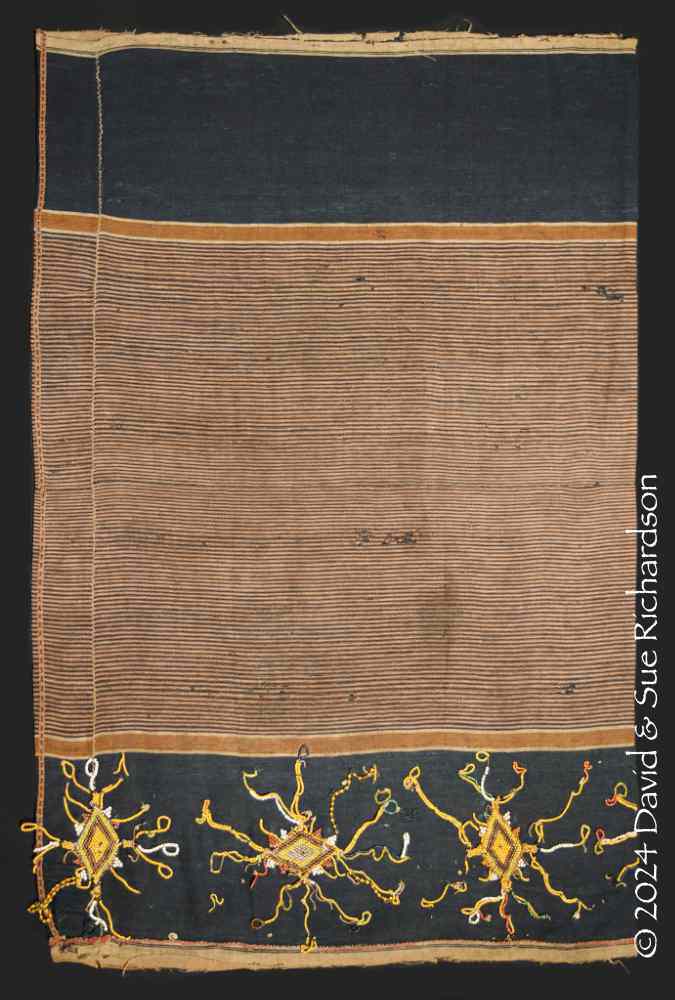

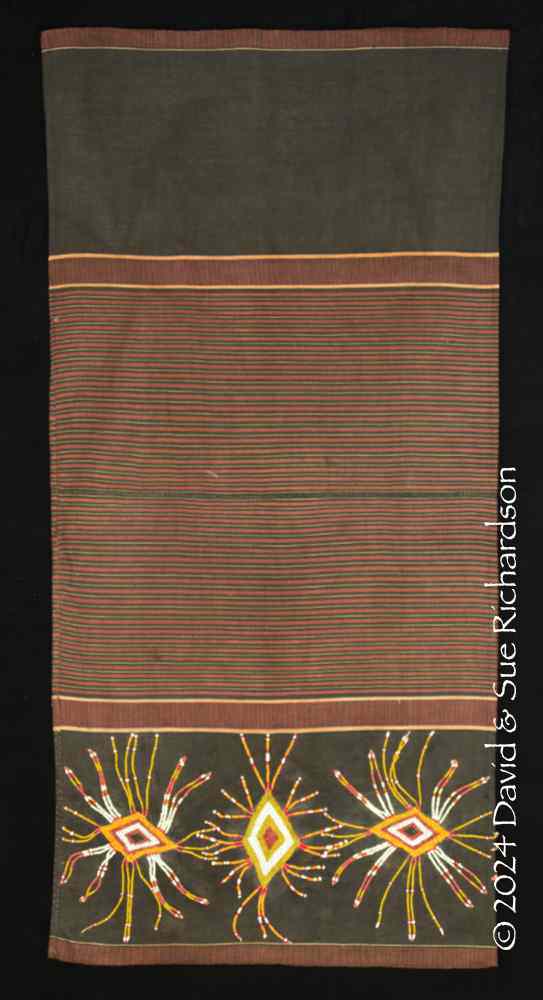

Lawo Butu

The lawo butu is a short two-panel sarong that is decorated with glass beads rather than ikat. Across the whole of the Lio region these are only found in kampong Nggela, although different styles of beaded sarongs are also found to the west, in the Ngada region, and to the east, in the Sikka region. Despite being simple, and devoid of ikat, the lawo butu is considered to be the village’s most sacred ceremonial sarong, treasured as a clan or family heirloom.

A lawo butu with no provenance

Collection of Yale University Art Gallery

Traditional lawo butu were plain woven from local hand-spun cotton. They had an indigo dyed central field decorated with narrow white and morinda warp stripes and wide plain indigo end sections flanked by narrow bands of morinda. The lower end sections were then embellished with small, roumd, coloured glass beads, the majority of which were yellow. The beaded motifs were always the same – a central diamond (or in rare cases a hexagon) termed a mata bili, (mata = eye, bili = round) sprouting many long wavy arms, the whole likened to an octopus, a maka kubi. However some liken the motif to the female vulva, suggesting it symbolises fertility. Some claim that the beads were imported by the Portuguese, who arrived on Flores during the sixteenth century.

Above and below: An old badly damaged lawo butu belonging to Sa’o Ria displayed inside the sa’o nggua

Another lawo butu owned by Sa’o Ria displayed by mosa laki Gabriel Manek

Because of its high status, the production of lawo butu was restricted to high-ranking women, particularly the wives of the mosa laki. Traditional versions seem to have been produced up to the 1930s, after which they ceased to be made since the ceremonies in which they were used were no longer performed (de Jong 1994, 223; de Jong 1996, 171). Consequently the lawo butu used for adat ceremonies during the latter part of the twentieth century were all old examples. De Jong estimated that just prior to independence over one hundred lawo butu must have been present in the village, but as some of them became unusable and others were sold their numbers declined. By 1996 there were probably a maximum of thirty pieces left in Nggela. A few of these remain up to the present day.

Despite being heirlooms, most of the surviving nineteenth and early twentieth century lawo butu are in very poor condition, with tears and holes in the fabric and missing or loose strings of beads.

Above: Mama Veronika, the late wife of senior mosa laki Lambert Muda standing in front of Sa’o Labo wearing an old badly damaged lawo butu. Below: A very badly damaged lawo butu displayed in Nggela in 2023.

An old photograph from Nggela showing three women wearing lawo butu beside local mosa laki. Undated.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the ceremonial lawo butu has mostly been worn over the lawo kéli mara, which was only came into existence at some time between the 1930s and the 1950s.

Above: Two women each wearing a lawo butu over a lawo kéli mara

Below: A woman wearing a long lawo butu photographed by Father Piet Petu

The lawo butu was traditionally worn by high-ranking women for two important ceremonial rituals:

- The ceremony of the rain dance or muré, a four-day ceremony authorised by the village council when, due to exceptional drought, starvation was imminent, or when after seven years of fallow, new swidden fields were cleared for the cultivation of mainly cassava and corn. According to local customary law, the period of cultivation of the fields is restricted to seven years on the village land in the west, and then seven subsequent years on the village land in the east. The muré dance was performed in the sacred village centre, the pusé nua, by the highest-ranking young unmarried women of the village who symbolised purity and fertility – the daughters of the mosa laki.

- The meditation or maru ceremony undertaken during the thatching of two of the most important ceremonial houses – the até sa'o nggua. The lawo butu was worn by married women from two of the highest-ranking matrilineal clans

These ceremonies were maintained up until the 1930s but then ceased due to the upheavals of the Japanese occupation during the Second World War. A shorter version of the rain dance was revitalised in the early 1960s at the behest of local government officials. However, one report claims that after the muré dance was performed at the court of President Soekarno in about 1963, Nggela was struck by a disastrous famine. The mosa laki responded by performing rituals and sacrificing a buffalo, sprinkling its blood into every corner of the village. After that, the community became reluctant to perform their sacred dances out of context.

By the 1980s these fears seem to have subsided. The muré dance was performed in 1987 for the visit of the district governor and again in 1988 for a visit of the provincial tourist authorities.

To see a performance of the muré dance, please click here.

A group of young women standing by the pusé nua in Nggela in the 1980s wearing lawo butu and lawo kéli mara

The following lawo butu was made in the early twentieth century by Mama Bhoa from Sa’o Labo who died in about 1965, aged around 75. It was worn in 1988 by her granddaughter, Paulina Hawo, for the special performance of the muré dance staged for civil servants from government tourist agencies.

A lawo butu made by Mama Bhoa from Sa’o Ria. Richardson Collection

Paulina Hawo (fourth from the left) performing the muré dance in 1988 wearing her grandmother’s lawo butu

There are two categories of traditional lawo butu:

- those that were, and still are, kept as an heirloom or inalienable possession of the house or sa’o. In the past each sa’o would have kept three or more lawo butu, along with ivory tusks and ancient gold jewellery. Trading such house possessions was taboo (piré) and would be punished by the ancestral spirits with illness.

- those that were owned as personal heirlooms by high-ranking women. These seem to have been made by high-ranking weavers up to the beginning of the twentieth century. They look the same as those that are collectively owned, but are less sacred because they are not linked to the ancestors or to a sa’o. Even so, selling them could be dangerous.

The following lawo butu falls into the second category. We suspect it was a later twentieth century example. According to Mama Getrudis Ero who was born in the early 1960s, it was made by her grandmother, Maria Nduru Muda. She was an aristocrat belonging to Sa'o Ria and the mother of Pak Thomas Nggomba, the mosa laki turu tena nata ae from Sa’o Ria. According to Willemijn de Jong, Maria Nduru Muda was a very talented and influential weaver who did high-quality ikat work from the 1940s to the 1960s. Gertrudis actually wore this lawo butu when she danced for President Megawati in Kupang in the early 2000s.

The lawo butu made by Maria Nduru Muda from Sa’o Ria. Richardson Collection

During the 1990s a few modern lawo butu were made in the neighbouring village of Pora, using commercial cotton and plastic beads. Then in 2009, Threads of Life encouraged Petronela Pape and her husband Kanisius Uba to make a lawo butu on commission, which they could later trade. The couple emphasised that they would need to perform the appropriate ceremonies before they could sell it. Since then, more have been made in Nggela, a few to be used in a local re-thatching ceremony and others to be sold. Unfortunately, the new lawo butu incorporate modern plastic beads with a rather harsh appearance

A modern lawo butu displayed in Nggela in 2014

Above and below: Two examples of modern crudely beaded lawo butu

One intriguing aspect of the lawo butu is that although it is worn by women it possesses a number of male characteristics (de Jong 1996, 171). Most obviously, it is clearly based on a male two-panel luka sarong decorated with simple warp stripes. Furthermore, the most sacred examples are collectively owned by the sa’o, which are patrilineal kin groups. Finally, it was down to the male mosa laki to authorise the performance of the muré fertility ceremony.

Return to Top

Men's Textiles

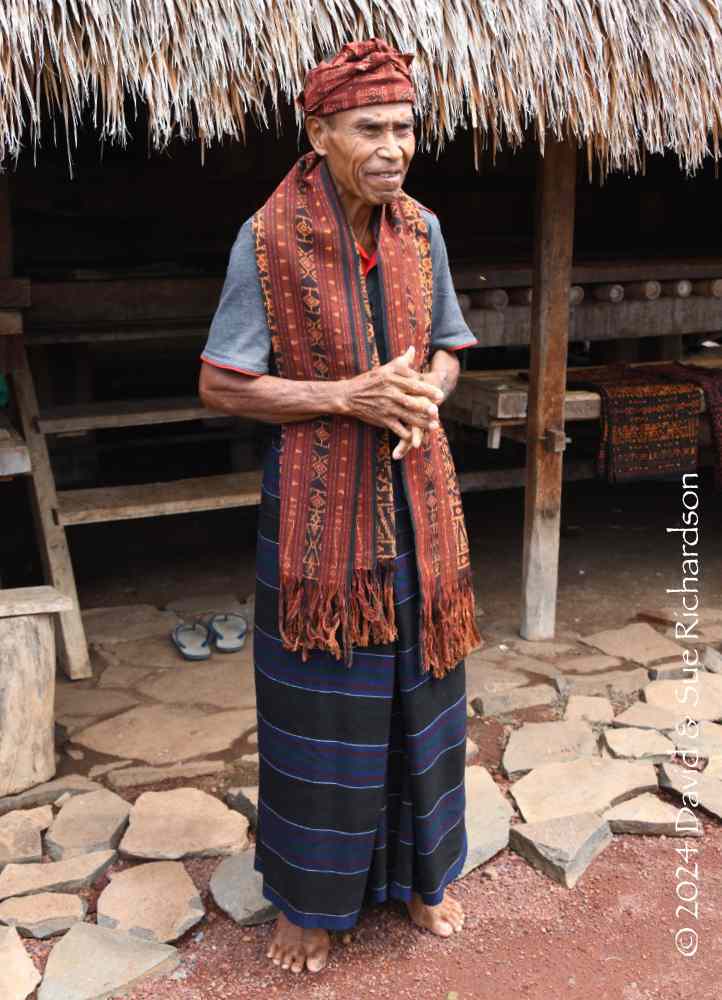

Today men wear western clothing for everyday wear. For ceremonial attire, however, men still wear a tubular hip wrapper and a shoulder cloth, both of which are called a luka, along with a small lésu head cloth. The latter can be a square of batik or of printed cotton.

The three mosa laki from Sa’o Ria dressed in ceremonial attire

Hip wrappers are never decorated with ikat, but ikat is found on four different kinds of shoulder cloth as well as on a wide variety of men’s scarves.

Return to Top

Luka Sarongs

Nggela luka sarongs are always two-panel and were traditionally decorated with squares or stripes. In the past there were several types (de Jong 1994, 216):

- luka mité or luka lo'o are black with stripes of various colours

- luka bara mité are white with black squares

- luka ria are large black cloths with fine red squares

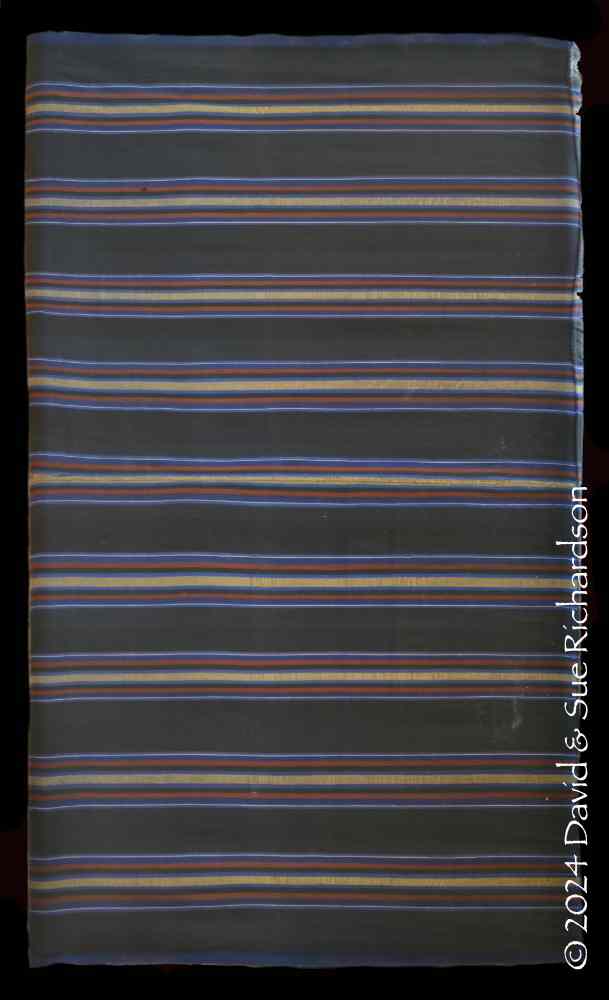

A modern luka mité

According to de Jong, production of the luka ria ceased in the last third of the twentieth century although existing examples were still in use in the 1990s (de Jong 1994, 225). However, in 2019 Mama Ango showed us a fine luka ria that she had recently woven. She told us that it could be worn by all men.

A big luka ria made by Mama Ango displayed sideways

Today the predominant men’s sarong is the luka mité, made from synthetically dyed commercial yarn that has been woven on the same back tension loom that is used for weaving women’s lawo.

A woman weaving a pair of luka mité in Nggela

The most senior mosa laki Lambert Muda wearing his luka mité and luka leté scarf

Above: A luka mité and a scarf hung up to dry in Nggela

Below: A laundered luka mité being stretched using water-filled plastic containers

Return to Top

Luka Shoulder Cloths

In the past there were several types of luka shoulder cloth made and worn in Nggela:

- luka sémba have a lattice of patola motifs covering the entire central panel.

- luka tégé or luka songgé sindé were prestigious shoulder cloths worn by middle aged men, but are no longer produced today. Songgé sindé means 'copy of a sindé (patola) cloth'.

- luka kapa are decorated with ship motifs.

- luka gamba bear motifs over the entire cloth. These tend to be of a non-stylised pictorial type, such as jewellery, animals or human figures.

- luka baro lombo have no ikat and are red and yellow with multi-coloured borders. They are worn by newly married men.

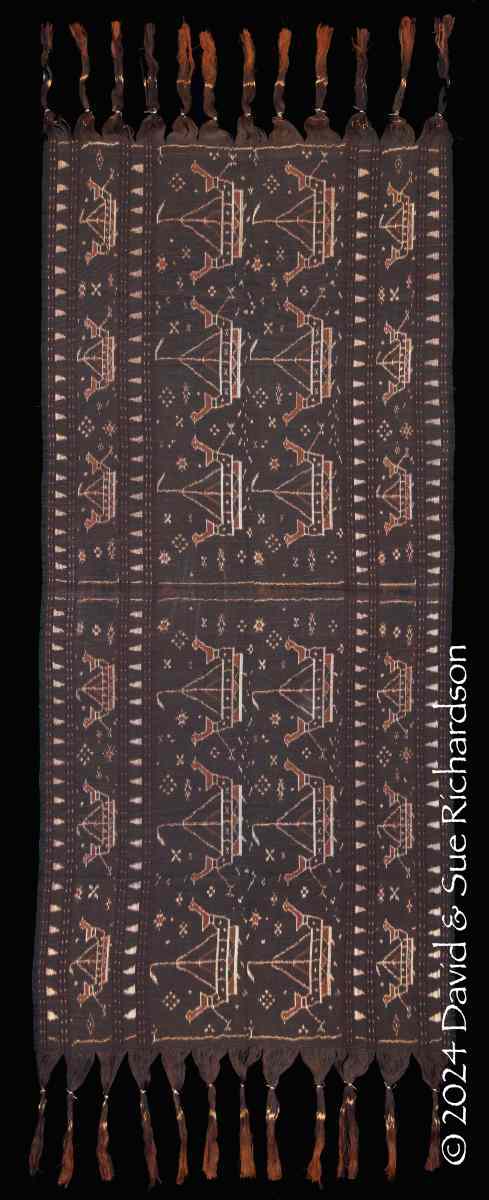

The Luka Sémba

The luka sémba is the highest status man’s cloth. In the past it could only be worn by a mosa laki at the most sacred adat rituals, such as the four-day loka lolo harvest festival. Over time these restrictions have eased, especially following independence. Today non-elite commoners can also wear the luka sémba, while some mosa laki wear a luka sémba every day. Consequently, most families in Nggela now have one or more of these shoulder cloths and every man is buried with at least one of them (Watters 1977, 89).

In addition, the luka sémba has become one of the most popular cloths sought after by visitors and traders. It has therefore become one of the most common textiles to be produced in the village.

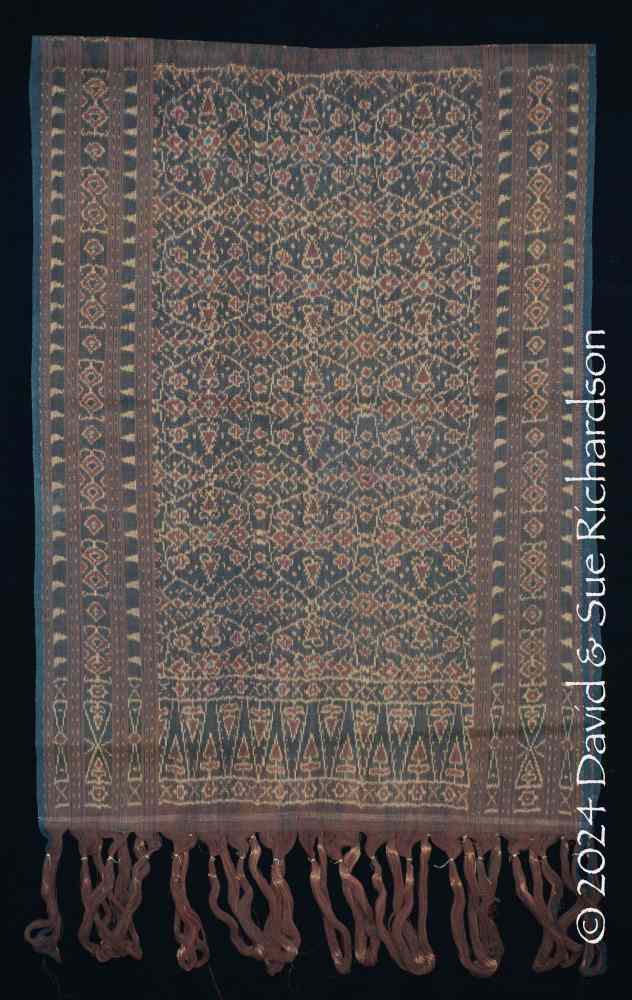

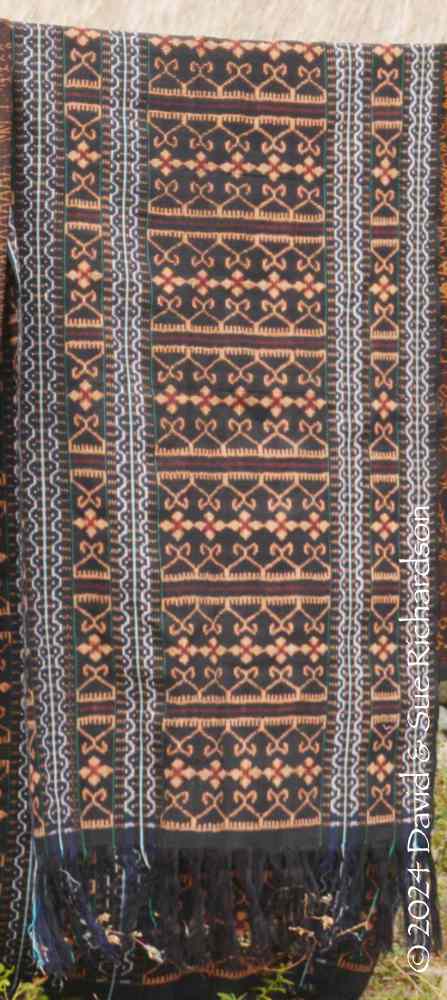

The naturally dyed example shown below with uncut fringes was probably woven in Nggela during the 1970s and has never been worn. It was part of a counter-prestation given in 1990 by the sa'o of a bride's father to the sa'o of her groom. It was subsequently retained as a family heirloom until we acquired it from the groom’s daughter-in-law.

A luka sémba used in a marriage gift exchange. Richardson Collection

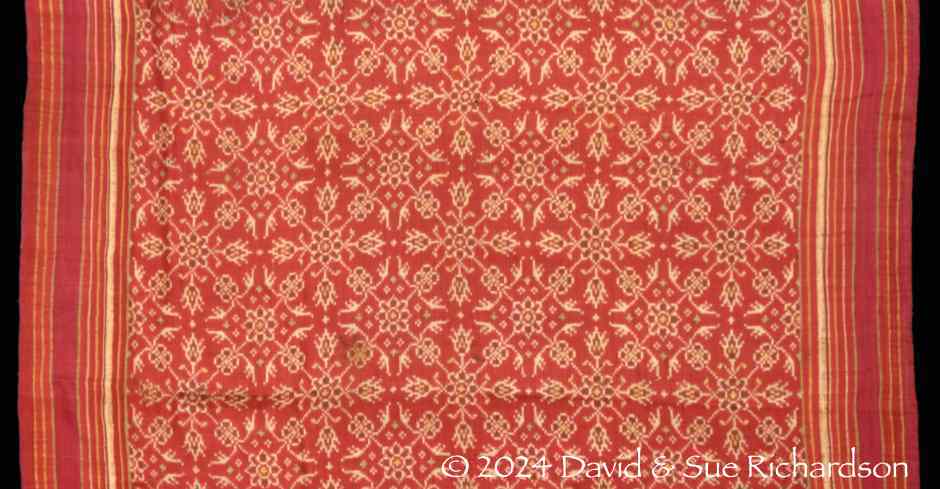

As can be seen from the above example, the luka sémba is woven on continuous warps as a single loom length of cloth. Clearly its design is heavily influenced by the Gujarati export patolu with the chhabdi bhat flower basket pattern (Alfred Bühler’s motif types 11 and 12). This was by far the most common design of patola exported to Indonesia, and the most common design to appear on Indian export cotton trade cloths.

Detail from an export chhabdi bhat patolu. Richardson Collection

The central field of the luka sémba contains a lattice of the octagonal sémba or patola motif and is framed by tumpal-like end borders of interlocking triangles enclosing arrow heads. The triple side borders have a central row of alternating single and paired diamonds sandwiched between rows of small cream triangles. The end warps have been simply gathered and lightly twisted.

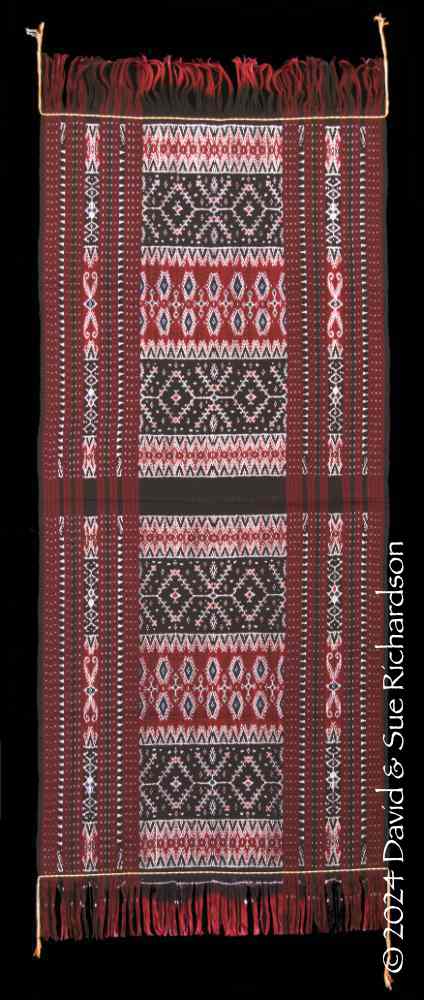

Above: A luka sémba woven by Mama Omakara, the late grandmother of Mama Fransiska. Richardson Collection. Below: A luka sémba woven by Mama Maria. Richardson Collection

Nggela weavers believe that they inherited the luka sémba and its hexagonal motif from their ancestors, its design having originally been created by an unknown local woman. They refer to the flower basket motif as the mata ke’a, mata meaning eye or motif. According to Mama Ango, the term ke’a refers to a small hexagonal basket with a cover that is used to hold rice and other crops during planting and harvesting ceremonies. The same term is applied to a coconut shell food container for holding meat that is used at ceremonies (de Jong 2016, 108).

Weavers interpret the mata ke’a as a symbol of the human body, elements of the motif representing the backbone, hips, liver and heart.

It is possible that the overall layout and design of the luka sémba has evolved over time. The late aristocratic weaver Nenek Maria Nduru Muda of Sa’o Ria, who was active between the 1940s and 1960s, is said to have been responsible for reinterpreting the pattern, having been initially taught it by her mother-in-law, who in turn inherited it from her mother (de Jong 2016, 108). However, weavers still believe that it is important that the mata ke’a motif remains unchanged, since modification could risk retribution from the ancestors.

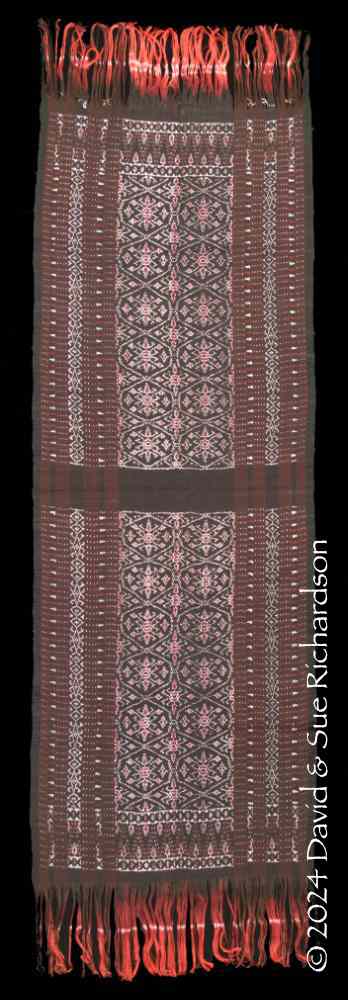

Above: A luka sémba made by Mama Veronika Riri in 1991. Richardson Collection

Below: A luka sémba made by Gertrudis Ero Nae in 2015. Richardson Collection

Although the luka sémba is not regarded as a sacred cloth like the lawo butu, it is still a high-status textile that is used in many important local ceremonies. Because of this it used to be considered a dangerous cloth to bind and weave. Indeed, up to the 1970s it was forbidden for any non-menopausal woman to bind a luka sémba, since to do so invited illness or tragedy. The weaver Petronela Ji’e recounted how in about 1975 Nenek Nduru had taught her how to bind the warps for the luka sémba. When Nenek Nduru fell ill shortly afterwards, Petronela feared that it was because she had shown her how to bind the ikat pattern (de Jong 2016, 109). These taboos seem to have loosened markedly during the 1980s, when many younger women started to bind this cloth to satisfy the lucrative demand from traders and tourists.

During the past two decades modern chemically-dyed versions of the luka sémba have been made using yellow or orange pre-coloured rayon, giving them a harsh and brutal appearance.

A luka sémba made in Nggela using yellow pre-dyed rayon

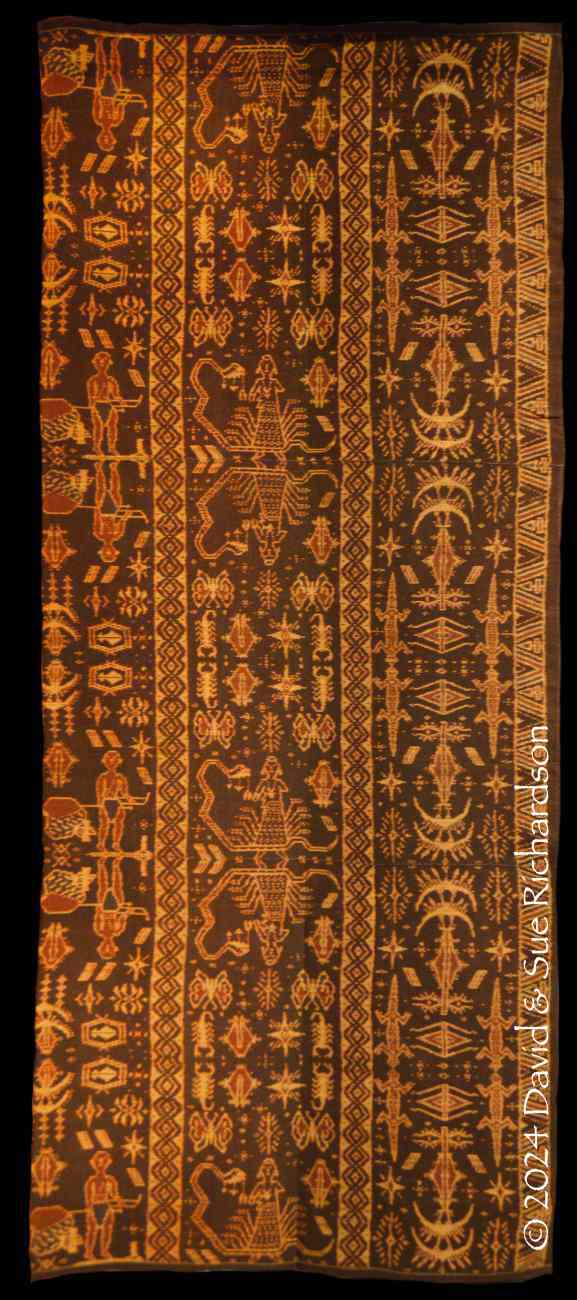

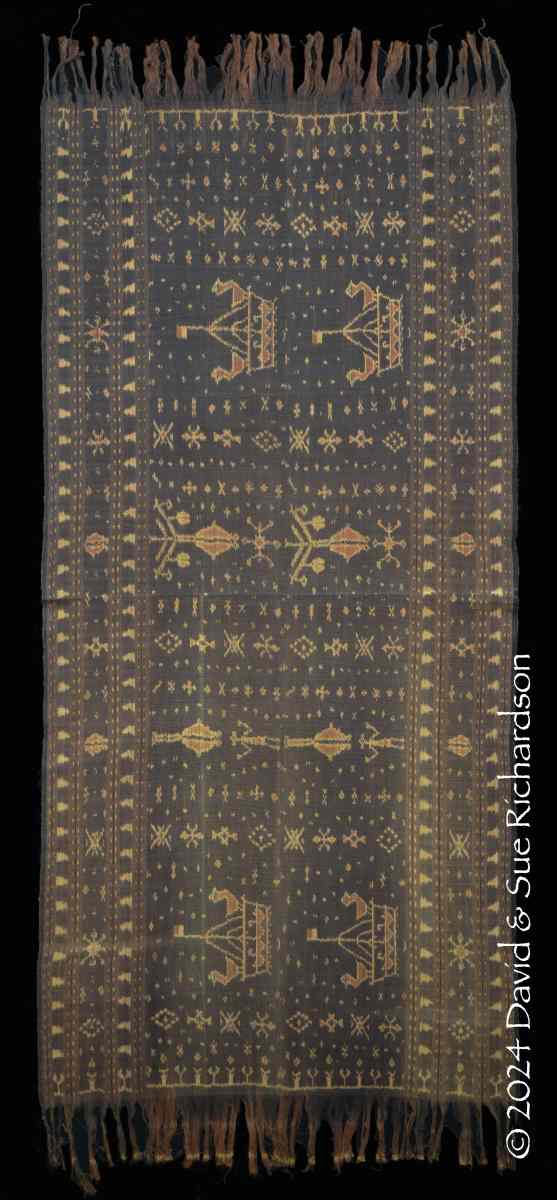

The Luka Kapa

Luka kapa are decorated with the kapa boat motif, which also appears on the lawo kapa in the form of a mirror-image pair of boats enclosed within a diamond. In the luka kapa it is depicted as a single vessel with a single mast and ducks seated on the bow and stern. Sometimes other motifs, such as gold jewellery are included alongside.

The kapa boat motif

Above: An old luka kapa from Nggela. Richardson Collection

Below: A luka kapa made by Marselina Wéndé, known as Mama Seli, from Sa’o Ria.

Other Types of Luka

Of the remaining types of luka, perhaps the luka gamba are the most likely to be encountered. However, luka gamba seem to be much less common than lawo gamba. Every example has its own arrangement of motifs.

A luka gamba displayed in Nggela

We have also seen a few other non-standard types of luka in Nggela, every one of which appears to be unique.

Above: A very unusual luka on display in Nggela

Below: Another unusual luka shoulder cloth with small lattices of hexagons

Several very different types of luka are made in Muslim villages located in the nearby Mbuli Valley. The longitudinal banded example below was made around 2005 by Reri Mese, who lives in Mbuli Wara Lau. It was acquired from her granddaughter. The four central ikat bands are decorated with elongated anthropomorphic and bird-like figures.

The luka Mbuli made by Reri Mese. Richardson Collection

The second synthetically dyed example was woven by Siti Fatima, who died in 1998 at the age of 65. She lived in one of the houses overlooking the beach at kampong Kopoone in Mbuli Wara Lau. The luka has a central band decorated with diamonds, a ‘flower basket’ patolu motif and stylised geckos.

A luka woven around 1980 by Siti Fatima in kampong Kopoone. Richardson Collection

The next two lukas were made in kampong Watu Rajo, located on the west side of the Mbuli River, 3½km south of Wolowaru. It is a mixed Christian/Muslim village that was founded eight generations ago. The first was made by Mama Tena in 2019. It is called a luka mata ria, the mata ria motif resembling pairs of eyes. The double diamond motif is called toko ika, meaning fish bone. Whilst mainly used by men, this luka can also be worn by women.

Above: The luka mata ria made by Mama Tena. Richardson Collection

Below: The luka mata ria made by Mama Sofia. Richardson Collection

The final example was made by Mama Sofia who was born in 1956. It has a double centre field filled with lattices of ‘flower basket’ type motifs, clearly based on the Gujarati chhabdi bhat patolu. However, the local villagers refer to it as a luka mata ria, even though it is not decorated with the mata ria motif.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon 1990. Kecamatan Wolojita Dalam Angka 1990, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kabupaten Ende, Ende.

Anon 2020. Kecamatan Wolojita Dalam Angka 2020, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kabupaten Ende, Ende.

Aoki, Eriko, 2006. The Case of the Purloined Statues: The Power of Words among the Lionese, To Speak in Pairs: Essays on the Ritual Languages of Eastern Indonesia, pp. 202-228 and 317-318, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Aritonang, Jan S., and Steenbrink, Karel, 2008. A History of Christianity in Indonesia, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Bello, Maria Florencia Yunita, 2021. Makna motif pada tenun ikat Ende-Lio, Thesis, Universitas Pasundan, Bandung.

Bühler, A., 1943. Materialien zur Kenntnis der Ikattechnik definition und bezeichnungen, geschichtliches, mechanische Verarbeitung des Garnes, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie 43, Supplement, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Bühler, A., 1959. Patola influences in Southeast Asia, Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. 4, pp. 4-46, Ahmedabad.

Bühler, Alfred and Fischer, Eberhard, 1979. The Patola of Gujarat. Double Ikat in India, Krebs, Basle.

Buis, Father Simon, and Beltjens, Father Piet, 1923. Ria Rago: Pahlawan Wanita dari Lembah Ndona, Societas Verbi Divini (Soverdi), Ende.

Cornellisen, P. F. J. J., 1929. Totemisme op Flores en Timor, Nederlandsch-Indië Oud & Nieuw, year 13, vol. 11, pp. 331-344, Den Haag.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1994a. Cloth Production and Change in a Lio Village, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, Hamilton, Roy (ed.), pp. 211–227, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1994b. Cloth as Marriage Gifts. Change in Exchange Among the Lio of Flores, Contact, Crossover, Continuity. Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America 1994,pp. 169–180, Textile Society of America, Los Angeles.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1997. Heirloom and Hierarchy. The Sacred Lawo Butu Cloth of the Lio of Central Flores, Sacred and Ceremonial Textiles. Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, Chicago 1996, pp. 168–177, TSA, Austin, Texas. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/853

de Jong, Willemijn, 1998a. Vom Brautpreis zur Mitgift? Heiratstransaktionen in Ostindonesien, Asiatische Studien, vol. 52, pp. 445–471.

de Jong, Willemijn. 1998b. Geschlechtersymmetrie in einer Brautpreisgesellschaft, Die Stoffproduzentinnen der Lio in Indonesien, Reimer Verlag, Berlin.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2000. Women’s Networks in Cloth Production and Exchange in Flores, Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, Koning, Juliette; Nolten, Marleen; Rodenburg, Janet; and Saptari, Ratna (eds),pp. 264–280, Curzon, Richmond, Surrey.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2007. Rice Rituals, Kinship Identities and Ethnicity in Central Flores, Kinship and Food in South East Asia, Janowski, Monica, and Kerlogue, Fiona, (eds), pp. 196–222, NIAS Press, Copenhagen.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2011. Kleidung als Kunst: Porträt einer Ikatdesignerin in Ostindonesien, Stoffe weben Geschichten: textile Kunstmaterialien im transkulturellen Vergleich, vol. 52, pp. 55–71, Jonas Verlag, Marburg.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2015. Luka, Lawo, Ngawu. Kekayaan Kain Tenunan dan Belis di Wilayah Lio, Flores Tengah. Maumere: Penerbit Ledalero. (Translation in Bahasa Indonesia of the ethnography of the book publication Geschlechtersymmetrie in einer Brautpreisgesellschaft. Die Stoffproduzentinnen der Lio in Indonesien. Berlin: Reimer Verlag, 1998, with a new introduction and conclusion).

de Jong, Willemijn, and Kunz, Richard, 2016a. Striking Patterns: Global Traces in Local Ikat Fashion, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Berlin.

de Jong, Willemijn. 2016b. Red Threads in Flores, The Common Thread, The Warp and Weft of Thinking, pp. 50-61, Kerber Verlag, Berlin.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2016c. The Shoulder Cloth luka semba: Being (Trans-)Local in Flores, Striking Patterns: Global Traces in Local Ikat Fashion, pp. 104-114, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Berlin.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2020a. Ikat Patterns in Flores, Indonesia, and the Global Fashion Trajectory, Fashionable Traditions: Asian Handmade Textiles in Motion, edited by Ayami Nakatani, pp. 19-40, Lexington Books, Lanham.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2020b. Dynamics of Ikat Weaving and Cloth Wealth in Nggela, Woven Cloth and Women Weavers in Nggela, Central Flores: Tradition, Development, and Cultural Policy, Jakarta.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2021. Dress as art: portrait of an ikat weaver in eastern Indonesia, Arts in the Margins of World Encounters, pp. 3- 26, Vernon Press, Wilmington.

Dietrich, S., 1983. Flores in the Nineteenth Century: Aspects of Dutch Colonialism on a Non-Profitable Island, Indonesian Circle, vol. 31, pp. 39-58, SOAS.

Elbert, Johannes, 1912. Die Sunda Expedition des Vereins für Geographie und Statistik zu Franfurt am Main, vol. 2, Druck und Verlag von Herman Minjon, Frankfurt am Main.

Elias, Alexander, 2018. Lio and the Central Flores languages, Master's Thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden.

Freijss, J. P., 1860. Reizen naar Mangarai en Lombok in 1854-1856, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. IX, pp. 443-530, Lange & Co, Batavia.

Hamilton, Roy W., 1990. Local Textile Trading Systems in Indonesia – An Example from Flores Island, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 604.

Hamilton, Roy W., 1994. Ende Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, Roy W. Hamilton (ed.), pp. 121–147, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Howell, Signe, 1989. Of Persons and Things: Exchange and Valuables among the Lio of Eastern Indonesia, Man, vol. 24, issue 3, pp. 419–438.

Howell, Signe, 1990. Husband/wife or brother/sister as the key relationship in Lio Kinship and Sociosymbolic relations, Ethnos, vol. 55, issue 3–4, pp. 248–259.

Howell, Signe, 1996. A Life for ‘Life’: Blood and Other Life-promoting Substances in Northern Lio Moral Discourse, For the Sake of Our Future: Sacrificing in Eastern Indonesia, pp. 92-109, Research School CNWS, Leiden.

Kennedy, Raymond, 1953. Field Notes on Indonesia: Flores 1949-1950, Human Relations Area Files, New Haven.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., 2015. Relasi struktur masyarakat dan tata zonasi permukiman adat di desa Nggela, Ende-Flores, ATRIUM, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 75-92.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., 2016. Struktur Organisasi dan Tata Zonasi Permukiman Adat di Desa Nggela, RUANG: Jurnal Lingkungan Binaan, vol, 3, no. 2, pp. 157-172, Denpasar.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., and Siso, Silvester M., 2019. Pengaruh perilaku masyarakat terhadap pola permukiman adat di desa Nggela, Kabupaten Ende, RUANG: Jurnal Lingkungan Binaan, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 201- 212, Denpasar.

Lalo, Yohanes, 2009. Kecamatan Wolojita Dalam Angka 2009, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kabupaten Ende, Ende.

Lee-Niinioja, Hee Sook, 2022. The Continuity of Pre-Islamic Motifs in Javanese Mosque Ornamentation, Indonesia, Archaeopress Publishing, Oxford.

Mbete, Aron Meko, 1985. Keragaman Pemakaian Bahasa Lio, Linguistik Indonesia, vol. 3, pp. 29-35.

Muda, Lambert, 2018, 2019, 2022 and 2023. Personal communications in Nggela.

Paru, Maria Alfionita; Sasongko, Ibnu, and Imaduddina, Annisaa Hammidah, 2018. Pola Organisasi Spasial Permukiman di Kampung Adat Nggela, Kecamatan Wolojita, Kabupaten Ende, Thesis, Institut Teknologi Nasional, Malang, East Java.

Pleìjyte, C. M., 1894. Notes on the Ethnography of Flores, Glimpses of the Eastern Archipelago, pp. 30-39, Singapore and Straits Printing Office, Singapore.

Prioharyono, J. Emmed M., 2012. Kekuasaan Politik dan Adat Para Mosalaki di Desa Nggela dan Tenda, Kabupaten Ende, Flores, Antropologi Indonesia, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 180-202.

Riedel, J. G. F., 1886. The island of Flores or Pulau Bunga: The tribes between Sika and Manggaraai, Revue colonial internationale, no. 1, pp. 66- 71.

Roos, Samuel, 1877. Iets over Endeh, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXIV, pp. 481-580, ‘s Hage

Rouffaer, G. P., and Juynboll, H. H., 1899. De batik-kunst in Nederlandsch-Indië en haar geschiedenis, H. Kleinmann & Co., Haarlem.

Sareng Orinbau, P., 1967. Nusa Nipa: Nama Pribumi Nusa Flores, Nusa Indah, Ende.

Sareng Orinbau, P., 1992. Seni Tenun Suatu Segi Kebudayaan Orang Flores, Seminari Tinggi St. Paulus, Ledalero, Nita, Flores.

Seran, Sixtus Tey, et al., 2005. Upacara Joka Ju (Tolak Bala) di Kelurahan Wolojita - Kecamatan Wolojita Kabupaten Ende, Dinas Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Unit Pelaksana Teknis Dinas (UPTD) Arkeologi, Kajian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional Propinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur, Kupang.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002a. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1900, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002b. Another Race Between Islam and Christianity: The case of Flores, Southeast Indonesia, 1900-1920, Studia Islamika, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 63-106, Jakarta.

Steenbrink, Karel A., 2003. Catholics in Indonesia 1808-1942: A Documented History, vol. 1: Modest Recovery 1808-1903, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Sugishima, Takashi, 1994. Double Descent, Alliance and Botanical Metaphors among the Lionese of Central Flores, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 150, issue 1, pp. 146–170.

Ten Kate, Herman, 1894. Verslag eener Reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesié, I. Flores, Tijdschrift van het Kon. Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Umar, Ibrahim Abdullahi; Najib Muh’d nor, Mohammed; and Wong, Y. C., 2013. Fastness Properties of Colorant Extracted from Tamarind Fruits Pods to Dye Cotton and Silk Fabrics, Journal of Natural Science Research, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 60-66.

Van Suchtelen, Bertho Charles Constant Margarethe Marie, 1921. Endeh, Papyrus, Weltevreden.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Veth, P. J., 1855. Het eiland Flores, Tijdscrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, vol. 3, pp. 153-184, Joh. Noman en Zoon, Zalt Bommel.

Viruly Verbrugge, Elisabeth Wilhelmina, 1923. Met de camera door Nederlandsch-Indië, J. H. de Bussy, Amsterdam.

von Wyss-Giacosa, Paola, 2016. Biography of a Collection – Reflections on the Flores Textiles of the Anthropologist Willemijn de Jong, Striking Patterns – Global Traces in Local Ikat Fashion, pp. 70-79, Museum de Kulturen, Basel.

Watters, Kent, 1977. Flores, Textile Traditions of Indonesia, Mary Hunt Kahlenberg (ed.), pp. 87-93, Los Angeles.

Weber, Max, 1890. Ethnographische Notizen über Flores und Celebes, Verlag von P. W. M. Trap, Leiden.

Weber, Max, 1902. Siboga Expedite I. Introduction et Description de l'Expedition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Wichmann, Arthur, 1891. Berich über eine im Jahre 1888-89 im auftrage der Niederländischen Geographischen Gesellschaft ausgeführte Reise nach dem Indischen Archipel, Tijdschrift van het Kon. Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. VIII, pp. 188-293, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Yamaguchi, Masao, 1989. Nai Kéu, a ritual of the Lio of Central Flores, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Rituals and Socio-Cosmic Order in Eastern Indonesian Societies, part 1, Nusa Tenggara Timur, vol. 145, no: 4, pp. 478-489, Leiden.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 21 February 2024.