Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kampong Nggela 2

Lio Linguistics

Ethnography of the Ata Lio

Ata Nggela Kinship

Marriage and Bridewealth

Changing Bridewealth Composition

The Mosa Laki of Nggela

The Ceremonial Cycle

The Joka Ju Festival

The Loka Lolo Ritual

The Muré Rain Dance

Scholarship

Bibliography

Go back to Kampong Nggela 1

Local Geography

Oral History

Recent History

The Old Ancestral Village - The Oné Nua

The Village Zones

The Sa’o House Societies

The Sa’o Lima Rua

The Other Seven Sa’o

The Supporting Houses

The Traditional Sa’o Building

Lio Linguistics

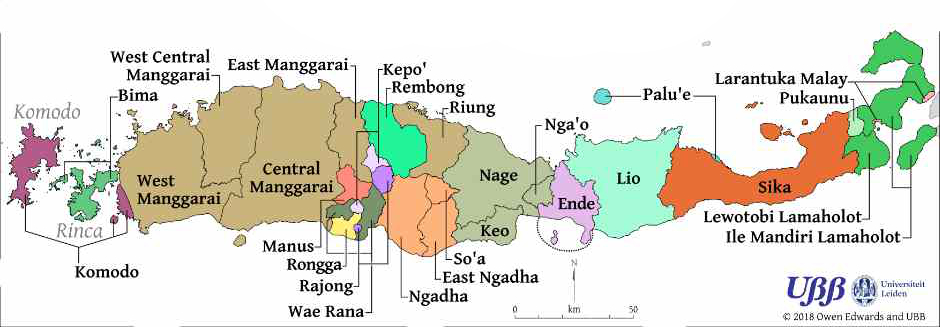

The Lio language is classified as belonging to the Central Flores group, which also includes the closely related languages of Ende, Nage, Keo, Ngada and Rongga (Elias 2020, 1). These languages all stand out from their Austronesian relatives because they are highly isolating – they have no obvious relationship to any other Austronesian languages such as those of neighbouring Manggarai, Sikka or East Flores.

The languages of Flores, reproduced with the permission of Owen Edwards

John McWhorter (2019) attempted to explain this by suggesting that the Central Flores languages were brought to Flores by immigrants from Sulawesi (possibly the south eastern Tukang Besi archipelago) in the relatively recent past, sometime after Austronesian speakers had already established themselves on Flores. These languages were then acquired by the pre-existing Austronesian speakers, but in an imperfect and simplified form compared to their parent language.

Alexander Elias (2020) has proposed an alternative theory, that Lio and the other Central Flores languages evolved from a now-extinct isolating language belonging to the huge Mainland and Island Southeast Asia linguistic area. This is because he has identified seventeen unique features that align them to the so-called Mekong-Mamberamo languages that had been earlier analysed by David Gil (2015).

Elias concludes that:

When the Austronesians began to settle Flores around 2500-1500 BCE, they encountered speakers of Mekong-Mamberamo type languages who were numerically dominant. The Austronesian settlers enjoyed a relatively high level of prestige over the pre-Austronesian inhabitants, who began to shift from their language to the Austronesian language of the settlers. These Mekong-Mamberamo speakers shifted to Austronesian in a relatively short period of time, leaving a heavy grammatical influence but very little lexical influence. The Austronesian settlers then integrated into the local population and adopted the restructured, Mekong-Mamberamo-like Austronesian language spoken by the majority of the population: Proto-Central Flores (or an immediate ancestor thereof). This ancestral community then differentiated in situ into the modern Central Flores languages with no further splits, forming an archetypal linkage (Elias 2020, 46).

Return to Top

Ethnography of the Ata Lio

The people of Nggela and the surrounding villages, including the Mbuli Valley, belong to the ethnic-linguistic group known as the Lio or the Lionese, locally called the Ata Lio. Traditionally the Lio lived in politically autonomous village clusters that were governed by customary law (adat) inherited from their ancestors.

The Ata Lio are nearly all officially Catholic, with the exception of a few isolated Islamic coastal communities. They are primarily an agricultural people, cultivating maize, cassava, millet and rice and raising livestock. Only the Islamic Lio depend upon fishing. For defensive purposes villages were traditionally built on a hilltop or steep slope around a circular flat open space called the kanga, in the middle of which was a female flat stone (the lodonta) topped with an upright male stone (the tubu). A village ancestral temple or keda was located at the end of the open space, although few of these remain today.

The Ata Lio have a system of double descent in which children are born into the patrilineal clan or suku of their father and the matrilineal clan or tebu of their mother (Sugishima 1994, 150). Male property, which consists of land, houses, bridewealth jewellery and animals, is passed down through the male line. Female property, which consists of personal jewellery and textiles, is passed down from mother to daughter through the female line. Patriclans mainly transfer rights on land. Matriclans also transfer rights on ritual and politico-jural offices as well as skills in craft and healing.

Prior to independence, the majority of Ata Lio society was stratified into:

- nobles, the ata ria (also ata ngga’e and mosa laki)

- commoners, the ana fai walu (or more fully the ana kalo fai walu)

- immigrants, the ata mai and

- slaves, the ata ko’o.

In several areas there were also a group of people regarded as coming from the lower class and they were referred to as the aji ana (the children of family members) (Mbete et al., 2006: 111-112).

Return to Top

Ata Nggela Kinship

The people of Nggela, the Ata Nggela, see themselves as a distinct and special sub-group of the Lio, with a culture and a language all of their own. They have a similar system of double descent, the differences being that the matrilineal clans are called kunu and in terms of inheritance, male property passes from the father to the son via the mother.

Children are born into the patrilineal clan or suku of their father and the matrilineal clan or kunu of their mother.

Suku

Patrilineal clans, suku, are village-based and are effectively lineages that each trace their genealogy back to a single founding ancestor, an embu. Because suku are exogamous, young men cannot marry women belonging to their own clan. In the past each suku had long established marriage alliances with two or more other village clans, and these alliances were asymmetric – males from clan A could marry females from clan B, but males from clan B could not marry females from clan A.

Women retain their suku membership for life and do not join their husband’s suku after marriage.

Kunu

Generally matrilineal Lio clans are non-localised and do not have ceremonial centres or corporate ceremonies. Consequently, women belonging to the same kunu can be widely dispersed geographically. This is far less the case in Nggela compared to other Lio villages because here marriage is matrilocal.

Individual kunu are regarded as originating not from ancestors but from specific plants or animals. Consequently, they are each connected to totems or tebu – specific food and behavioural taboos related to animals and plants (de Jong 2007, 222).

Just like suku, kunu are exogamous.

Kunu are traditionally stratified into three castes or social rankings:

- the noble kunu composed of the high-ranking people (the ata ria or big people), the descendants of the high-status founding clans of the adat community,

- kunu composed of middle-ranking people and commoners (ana fai walu), who descend from the junior clans that settled afterwards, and

- kunu composed of low-ranking people (ata ko'o), who are the descendants of former slaves.

Sa’o

Just like suku, the membership of a ’house’ or sa’o is transferred in the line of the father, as are the rights to land (de Jong 1996, 169). In most respects the membership of a sa’o is more important than the membership of a suku. However, sa’o are not equivalent to suku – the members of an individual sa’o may belong to several different suku.

Sa’o lineages are divided into smaller podo (pots), somewhat like an extended family, and consist of a group of brothers along with their families (de Jong 2013, 267). In the past they may have formed a single household, each providing agricultural produce as tribute to the head of the podo.

Because of the asymmetrical alliance system of marriage, exogamy rules have to be followed with respect to both sa’o and kunu as well as suku. This can create a real problem for young couples who may not know their distant relatives. In some situations, they have to ask their older relatives for advice (de Jong 2007).

At the time of marriage, a woman formally moves from the sa’o of her birth to the sa’o of her husband (de Jong 2007, 210). Following the exchange of bridewealth, the bride undertakes the ritual of distributing cooked rice to the groom’s family, after which she officially becomes a member of her new husband’s house.

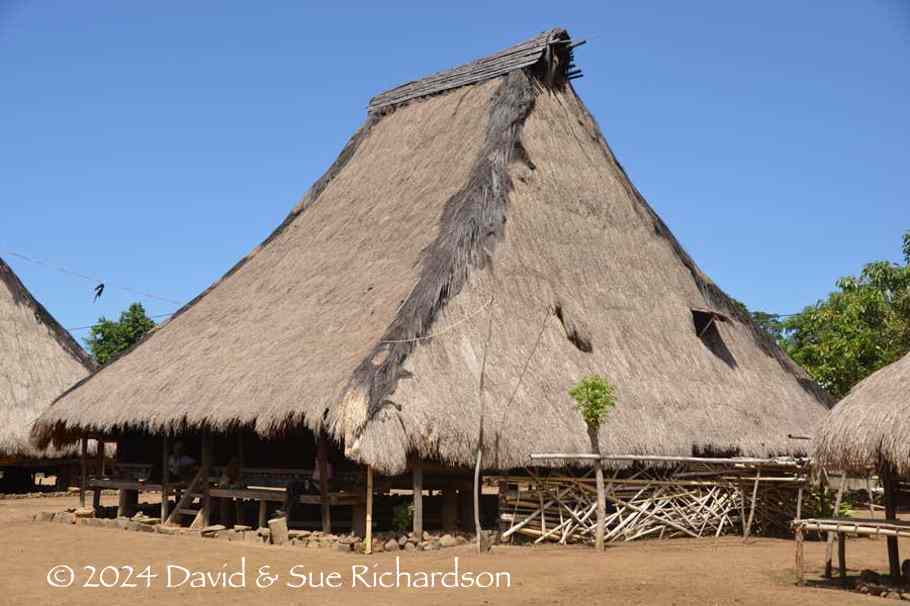

The nobility of Nggela is spread across twenty-eight named houses or sa’o, each of which has a physical clan house (rumah adat) known as a sa’o nggua, literally ‘houses of the agricultural rituals or festivals’ (de Jong 2007, 204). Each house has a founding ancestor – thus Sa'o Rore Api was founded by Nogo and Sa’o Ria was founded by Nggela. This is where the agricultural rituals used to be celebrated and where the ancestors of that sa’o are worshipped (see Howell 1995).

Sa’o Ria before it was destroyed by fire in 2018

Fourteen of the twenty-eight sa’o are headed by a titled noblemen called a mosa laki (essentially ‘distinguished man’) and a titled noblewoman called a fai ngga’é (‘distinguished woman’). While these fourteen are headed by just one mosa laki, Sa’o Ria is occupied by three mosa laki. So once again, Nggela is unique in having seventeen mosa laki while most Lio villages have only seven. The fourteen highest-ranking sa’o are located just inside the boundary of the ceremonial heart of the kampong, the oné nua, arranged in the form of an oval.

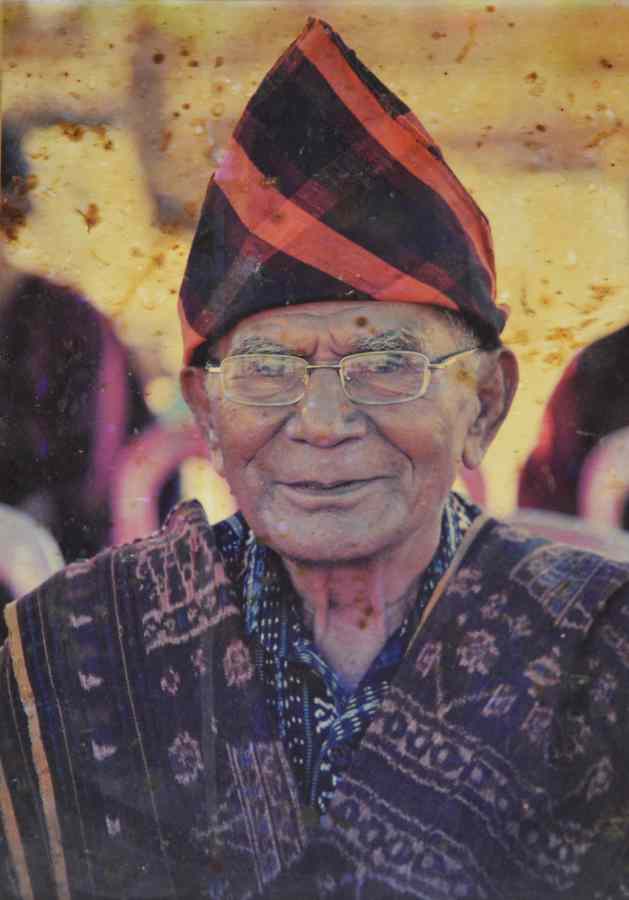

Above: mosa laki Gabriel Manek. Below: mosa laki Thomas Nggomba

Prior to independence the mosa laki held both political and spiritual power and together formed the village council, holding the power to allocate land. Following independence, political authority was transferred to an elected kepala desa whose role is overseen by the camat of Kecamatan Wolojita. The most recently elected kepala desa is Laurensius Kale, who was inaugurated by the Regent of Ende on 30 January 2020. The previous kepala desa was Vincensius Beo.

Today the responsibility of the mosa laki is limited to overseeing the spiritual life of the village and for organising the annual cycle of rituals, most of which are or were related to the planting and growing of mountain dry rice.

Not only are marriage practices still heavily influenced by the ranking system, but membership of the noble matrilineal clans is decisive for titles and positions and even confers special privileges regarding the ikatting of textiles.

Traditionally Nggela society has been more stratified than most other Lio villages. In 1990 Willemijn de Jong uncovered large differences in wealth between different Nggela households (de Jong 2013, 275). Wealthy households might own four plots of fertile land, some cultivated by sharecroppers, several pieces of valuable gold jewellery, cash savings and around 20 pieces of ikat cloth. Poor households owned no land or at most one plot, no jewellery, limited cash and just one of two pieces of cloth. Rivalry concerning status dominated village life and permeated social relations, especially regarding the staging of life-cycle and agricultural ceremonies (de Jong 1994a, 170).

Following independence, this ranking system has lost any formal authority – now all Indonesians are equal in law. However, it still exerts a strong influence informally on the political, economic and social life of the village. Even today, only noblemen and noblewomen belonging to the nine top kunu are eligible to hold the titled offices of mosa laki and fai ngga’é (de Jong 2007, 214-215).

Return to Top

Marriage and Bridewealth

As mentioned above, each sa'o is exogamous and has a fixed asymmetric relationship with every other sa'o as either a 'wife-giver' (ine amé or nara amé) or a 'wife-taker' (wata ané or weta ané). In many cases it is not the whole sa’o who act in this role or even the entire podo, but a group of closely related families within it. As an example, among the highest status houses, Sa’o Labo is a wife-giver, supplying wives to Sa’o Ria, one of the largest and most wealthy of all the houses.

According to adat, every Lio marriage must entail the exchange of bridewealth, known as ngawu. In Nggela the sa'o of the wife-takers provides bridewealth consisting of gold (in the form of vulva-shaped earrings, wea) if available, money, buffaloes, houses, dogs and pigs, while the sa’o of the wife-givers makes a counter-prestation of cloth, rice, palm wine and cooked food. Generally, only high and middle-ranking families can afford this level of bridewealth.

Whereas in most Lio villages post-marital residence is patrilocal, a married couple reside with the husband’s parents – in the case of Nggela, it is matrilocal.

In the past marriage was prescribed between cross-cousins – a boy should ideally marry his mother’s brother’s daughter. However, since the mid-1920s the Catholic Church has steadily undermined this tradition.

In Nggela, three kinds of marriage are performed:

- marriage by formal courtship (tana ale'), the most prestigious,

- marriage by informal courtship (po'u uta or wangga kaju) and

- marriage by elopement (paru nai).

Some couples arrange to marry by eloping, thus avoiding the huge bridewealth demanded by the bride’s parents. However, in Nggela such brides were never respected.

Willemijn de Jong has documented the process of marriage by formal courtship in some detail (de Jong 1994, 174-177; de Jong 2007, 209-213). This has evolved since the early 1900s, partly due to the influence of the Catholic church. In the early 1990s this type of marriage had three main stages: the betrothal, the exchange of the main bridewealth and the wedding ceremony. This whole ritual takes around two years to complete, and at each stage there is an exchange of bridewealth and a counter-prestation of textiles. In Nggela women generally do not marry before they are 25 and men not before they are 30.

To arrange the marriage the parents of the young man negotiate indirectly with the parents of the young woman using an intermediary. The most important topic is the quantification of the bridewealth and the counter-prestation. In Nggela marriage is associated with the highest amounts of gift exchange, including both the bridewealth and the counter-prestation, especially the number and quality of textiles.

Once the marriage is agreed, the betrothal – the nai one' – is officially announced to a small family circle in the house of the woman’s parents. This is formalised by an exchange of gifts. Three textiles – a man’s sarong and shoulder cloth and a woman’s sarong, are gifted to the future husband, while his family gift gold earrings, if they have any, and money via the intermediary. Later, livestock such as a horse and a pig, along with betelnut, are gifted to the young woman’s parents. If gold jewellery has been given, the parents of the bride reciprocate some days later with further large gifts of food. These gift exchanges establish a long-term affinal alliance between the two families.

The couple are now engaged, so the prospective bride is expected to keep her virginity while the prospective groom is no longer free to be sexually active.

The exchange of bridewealth is a public event that has to be witnessed by the village community. It begins with the assembly of both the bridewealth and the counter-prestation at the respective homes of the groom and bride. Members of each extended family (kinsmen) bring livestock and money, and cloths and rice respectively. Now the bride’s family can hold the feast for the delivery of bridewealth (the nggewa té'é) where the groom’s family, along with their relatives, host the bride’s family and their relatives. The latter donate livestock – for example two horses, five pigs and one goat, money (for example IDR 400,000), and perhaps another pair of gold earrings. A bride whose family receive bridewealth involving gold jewellery is seen as having higher social status than one for whom no gold jewellery is given.

In return, the parents of the bride and their kinsmen offer and bundles of textiles (as an example, fifty-three pieces) and betelnut to the groom's parents and kinsmen, a ritual known as tolo nata. After the completion of the gift exchange, the family of the bride serve a lavish meal of meat and rice, the bride and her friends serving the cooked rice to her in-laws. The bride is now officially incorporated into the patrilineage (sa’o) of the groom.

If the bridewealth included gold jewellery, some days later the parents of the bride donate a large gift of raw and cooked food to the parents of the groom.

De Jong has provided an example of the quantities of gifts that were exchanged in 1992 for the marriage of a bride belonging to one of the highest-ranking families in the village (de Jong 2007, 222). The bridewealth was composed of two pairs of gold earrings, ten horses and one million Rupiah, while the counter-prestation consisted of 87 textiles and 500kg of rice.

In certain cases, the exchange of goods can turn out to be contentious. If the bridewealth fails to meet the expectations of the bride's parents, they are entitled to demand more animals or money. Likewise, if the counter-prestation fails to meet the expectations of the groom's parents, they can request more textiles. This can create friction between the mother-in-law and the daughter-in-law and between the mother and her daughter. Occasionally it can disrupt the marriage.

On the eve of the wedding, the tau nika, the bride’s mother's brothers donate wedding clothing to the groom. The official wedding ceremony normally takes place in the local Catholic church of Santo Theresia. The final stage of bridewealth exchange takes place after the completion of the wedding mass. The groom’s family donates livestock, such as two pigs and one goat or one cow, money and in rare cases more gold jewellery, while the bride’s family reciprocate with rice.

After the wedding ceremony, the married couple first visit the house of the groom before going to the house of the bride for the wedding feast. This can involve several hundred invited guests, each of whom bring small gifts such as money, household goods or a textile. Just before the food is served, the kinsmen of the bride perform the final ritual of donating textiles. As an example, this might amount to twenty-five pieces of cloth.

Following the wedding, the newly-married couple will eat for four nights in a row with the close kinsmen of the bride. In the past the couple were not allowed to change their clothing during this period, only taking a ritual bath at the very end. The couple were now man and wife, responsible for their own household. Initially they will often live in the house of the bride’s parents until they can afford a house of their own.

Return to Top

Changing Bridewealth Composition

Willemijn de Jong (1994, 169) has found that the composition of the bridewealth and counter-prestation have changed markedly over the past century. For the highest-status families who exchange the largest bridewealth:

- in 1910, 20 pairs of gold earrings were given in return for 3 textiles

- in 1950, 5 pairs of gold earrings were given in return for 6 textiles

- in 1994, 3 pairs of gold earrings were given in return for 50 to 100 textiles

Over the century, much of the gold jewellery in Nggela has been sold off, primarily to pay for school fees. Gold has therefore had to be substituted by money.

Regarding textiles, wealthy families were the first to benefit from the increasing availability of machine-spun cotton from the 1930s onwards, thus increasing the number of cloths that a woman could produce, while decreasing their value. After independence, the aristocratic women lost their monopoly on certain ikat designs, so commoners could produce cloths that were previously taboo. Furthermore, wealthy weavers could employ poorer weavers to work for them and produce more cloth. Finally during the 1970s, the widespread availability of synthetical dyes raised productivity further. The quantity of textiles increased further, while their value declined.

Return to Top

The Mosa Laki of Nggela

The mosa laki were formerly the high-status elders who held political, legal and religious power across the village. Since independence they have retained their high standing, but only control the ceremonial aspects of village life and the application of customary law (adat). Their role is hereditary and passes from father to eldest son.

The term mosa laki is loosely translated as ‘distinguished male’. In relation to the nearby Nage people who live to the west of Ende Regency, Gregory Forth has explained that the term mosa generally refers to a male mammal but especially to a male water buffalo (Forth 2009, 503; Forth 2016,151). At the same time, while laki normally refers to a man or male, among the Nage it also means ‘true, genuine or legitimate’. The term therefore conveys the essence of a powerful and legitimate male ruler.

While there are twenty-eight traditional clan houses or sa’o in Nggela, only fourteen are headed by a single mosa laki, while one further clan house accommodates three mosa laki. The other thirteen have no tradition of a mosa laki. The seventeen noble village elders formerly constituted the village council with political power over the village. Today, this responsibility is held by an elected village head or kepala desa. The mosa laki are now confined to their religious role, which is to mediate between their followers (ongga) and the ancestors (du’a bapu).

The mosa laki are in charge of the annual cycle of ceremonies that begin with the start of the growing season and end with the harvest ceremony. Although they have embraced Catholicism, their belief in natural forces remains strong. If an event occurs that is beyond human control such as famine, crop failure or an outbreak of an unusual infectious disease, they are responsible for organising the appropriate adat ritual. They believe that such events arise because of deficiencies or errors in the people’s daily lives. The appropriate traditional ceremony will neutralise the causes and restore the natural harmony.

One example is the traditional ceremony that revolves around the muré dance, which was performed if the village was affected by a prolonged drought. The dance is performed by chaste teenage girls accompanied by chanting to encourage the onset of rain.

As of April 2024 the three most senior mosa laki in order of status are:

- the head or leader of the seventeen mosa laki is the mosa laki pu’u iné ame from Sa’o Labo, which is where the first ancestor settled. This Sa’o could be identified by its buffalo skull front step. Pu’u translates as source or trunk, and essentially means origin while iné ame means mother-father. He delegates authority to the lower-ranking mosa laki. This role is currently held by Lambertus Muda who inherited his position from his father. His wife Veronika sadly died of cancer on 11 April 2019, which left him with one daughter, Merlin Muda.

- the executive and second most senior mosa laki is the mosa laki pu'u from Sa’o Ria, which contained a religious altar and several large elephant tusks. This role is held by Pak Gabriel Manek, who must ask Lambertus for permission to initiate a ceremony.

- the judge and the third ranking mosa laki is the mosa laki ria béwa (the great priest, ria being great and béwa being long, high or deep) from Sa’o Leke Bewa. This role is held by Vinsensius, who is a non-resident and lives in Ende.

The interior of Sa’o Ria in 2017

The top seven mosa laki as of April 2024 are the three mosa laki listed above plus:

- the mosa laki tau koe uwi from Sa’o Meko, tau meaning guardian, koe meaning to dig and uwi meaning tuber (cassava). Laka Doane Marsianus is the head of agriculture and crops. He also guards and supervises the kanga ria court and graves.

- the mosa laki tau dai ulu nua from Sa’o Tua. Tau dai meaning guardian and ulu nua meaning north village. This is Pelipus Buga, known as Fred, responsible for the care of the village, including the buildings and graves.

- the mosa laki tau piara nggo lamba from Sa’o Pemo Roja, tau meaning guardian, piara meaning to raise, nggo meaning gong, lamba meaning drum. Raimondus Redu is in charge of music.

- the mosa laki tau tunu from Sa’o Ndoja, tau meaning to guard, and tunu to roast or cook. Aloysius Poto is the mosa laki tau tunu in charge of sacrifices.

In addition, there are ten further mosa laki:

- the mosa laki nata ae from Sa’o Ria, responsible for receiving guests, nata meaning to chew betel and ae meaning water. This is Pak Thomas Nggomba.

- the mosa laki mboto au from Sa’o Bewa, mboto meaning many and au meaning bamboo. This is Aloysius Sika.

- the mosa laki ru’u tu’u jaga tau rara from Sa’o Ria, responsible for resolving conflicts in the community. This is Ambrosius Gengu. Note that tu’u is to stop, and jaga is to guard or keep watch.

- the mosa laki ndeto au from from Sa’o Ame Ndoka is Aurelius Mbulu. He is an adat judge, responsible for safety and order in the village. An ndeto is an ancient firearm.

- the mosa laki ndeto au from Sa’o Embu Laka is Selvisius Nabi. He is also an adat judge.

- the mosa laki tau dai ulu ae from Sa’o Wewa Mesa is Damianus Jenasem. Because his sa’o is the only one facing south, he is responsible for guarding the coast against foreign ships.

- the mosa laki gao lo kaka taga from Sa’o Samba Jati is Paulinus Tali. He assists the other mosa lakis in performing village rituals.

- the mosa laki from Sa’o Mberi Dala is Daniel Danu.

- the mosa laki bei nggo from Sa’o Watu Gena is Eduardus Mberu. He is responsible for music and for helping the other mosa lakis.

- the mosa laki tau sani from Sa’o Tana Tombu is Melkiades Paru. He assists the other mosa lakis in performing village rituals.

Return to Top

The Ceremonial Cycle

Men are responsible for the production of food, today mainly for subsistence. This activity is associated with an elaborate system of agricultural rituals (nggua) of socio-political and religious significance.

The annual list of traditional nggua ceremonies in 1961/1962 in Nggela was as follows

| October | Ka Uwi (‘Eat Cassava’). The start of the planting season |

| November | Wela Sambi Loa Telo Teke Gha'i Manu Raga Gha'i |

| December | Paki Gha'i Ata Waga Loa Telo in Sa'o Ria |

| January | |

| February | Lao Mba'o) Ka Mera Kewe Todo Obo |

| March | Naka Lea Lo'o Naka Lea Ria Koe Uwi/Ka Kobho Wangga Jawa Ata Toba Wangga Jawa Ata Rewo |

| April | Pa'i Lolo Toa Koli |

| May | Loka Lolo |

| June | Loka Pare Joka Ju |

| July | |

| August | |

| September |

Source: From the records of Ya Lerux Sare, the former mosa laki pu'u

Aside from these, there were many other traditional ceremonies that were carried out at some time or another: Kema Keda, Kema Sa'o Nggua, Wake Mosa Laki, Tane Mosa Laki Pu'u Mata, Muré, Joka Nua, Joka Ule Mela, Nara Nio, Ra Nua, Nika Adat, Simo Ata Mai, Sewu Api Sa'o (Nua Nula) and Loka Ae.

Return to Top

The Joka Ju Festival

Joka Ju is a ritual that takes place every year according to the traditional calendar of Nggela, normally in June or July following the harvest in April/May. The purpose of the ceremony is to purify the village and protect its population at the completion of the agricultural cycle. Joka means to reject while Ju Angi refers to pests or disease.

The Joka Ju ritual is considered sacred, because for four consecutive days the Nggela people are not allowed to carry out any normal activities such as gardening, lighting a fire outside of the house, picking growing plants, fighting, or even burying the dead. They are only allowed to have fun. People who violate the prohibition can be punished or fined.

On the day before the festival, the villagers round up their livestock while the mosa laki go from house to house asking for donations of rice. In the evening the families ritually feed their ancestors to the accompaniment of gongs and drums.

The ceremony begins the following day, starting from Sa’o Ria in the late afternoon with a procession to the beach led by the mosa laki turu tena nata ae. As he walks, he scatters rice from the house’s granary in order to clear the path of any troublesome spirits. He is followed by the other six senior traditional leaders – the mosa laki pu’u iné ame from Sa’o Lobo, the mosa laki pu'u from Sa'o Ria, the mosa laki tau tunu from Sa’o Ndoja, the mosa laki tau kowe uwi from Sa'o Meko, the mosa laki dai ulu nua from Sa’o Tua and the mosa laki bei nggo from Sa’o Watu Gana.

On the beach the traditional leaders stop at three locations, one being the Penga Iu rock. There they prepare an offering by cooking rice, shrimp and egg in bamboo containers over a fire. After shouting several times to frighten off the negative spirits, they send the offerings out to sea in small boats made of bamboo, sending away any negative forces so that they cannot disturb the community over the following year.

The next day the mosa laki pu’u walks around the village with the other mosa laki, starting from the south and visiting the east, west and the northern parts of the village. He places an offering containing a small shrine that looks like a miniature traditional house. He touches his foot to the miniature stairs of this shrine as though he was entering the house. He repeats this ritual again as he walks back to the south of the village. Throughout the procession, all the villagers make loud noises, banging the walls and floors of their houses.

On the completion of this ritual, one of the mosa laki climbs onto a rock, the highest point in the traditional village, and announces to the community that from this point on it is forbidden for outsiders to enter the village, for anyone to work in the fields or cut down trees until the completion of the ritual in four days’ time.

The final days of the Joka Ju ceremony are reserved for celebrations. The villagers come together to enjoy traditional dances such as Gawi and Wanda Pa’u to the accompaniment of gongs and drums.

Return to Top

The Loka Lolo Ritual

The Loka Lolo is the traditional annual harvest festival for sorghum (jagung solor). It normally takes place between May and July, the exact timing being decided by the mosa laki pu'u. Its purpose is to allow the villagers and their leaders to express their gratitude to their ancestors for a successful harvest.

It begins when the mosa laki announce that it is time to harvest the sorghum crop from the fields. The sorghum is cut and brought into the village where the seeds are removed from the stems.

The head of each family brings their harvested sorghum to their sa’o nggua, where the women collect it in large baskets. Some of the young sorghum is fried and then pounded in a mortar to make sorghum flour. Some of this is then sprinkled around the centre of the Nua Oné.

Women with their baskets of sorghum inside Sa’o Ria

All of the baskets are then carried to the Kanga Ria where their contents are accumulated in one huge basket. Some are placed onto the offerings to the ancestors. Several of the mosa laki take some of the sorghum seeds in small baskets and scatter them around the traditional settlement starting from the Kanga Ria, walking south to Sa'o Tana Tombu, then back to Kanga Ria. Finally, the mosa laki sit on the Kanga Ria and eat and drink together.

The mosa laki standing around the large basket of sorghum

After the completion of the ritual, the male residents, especially the younger ones, are divided into two groups, usually those who reside in the north part of the village and those that reside in the south. They then engage in an energetic ritual play fight in which each side is threatened but nobody is injured.

Return to Top

The Muré Rain Dance

In the past the ceremony of the rain dance or muré was a four-day ritual authorised by the village council. Every once in a while, the villagers would be affected by a severe drought, damaging their crops. As food stocks dwindled the villagers faced the prospect of starvation. They appealed to the mosa laki to organise the muré ceremony, the primary purpose of which was to appeal to the ancestors to bring rain.

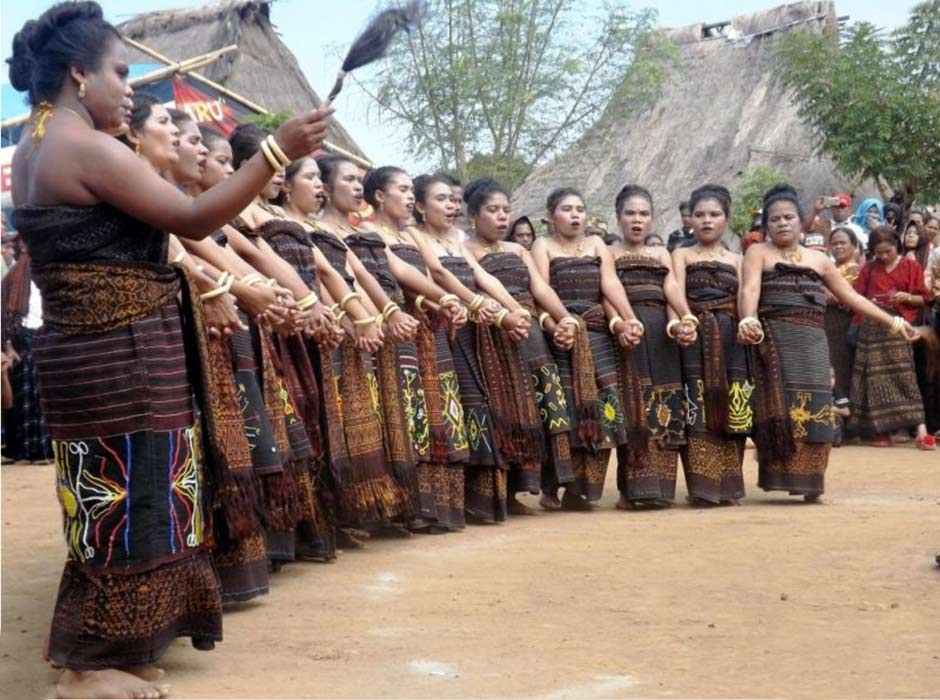

The muré dance was performed in the sacred village centre, the pusé nua, by the highest-ranking young unmarried women in the village, who symbolised purity and fertility.

There was one other situation in which the muré ceremony was performed. According to local customary law, the period of cultivation of the fields was restricted to seven years on the village land to the west, and then seven subsequent years on the village land to the east. The ceremony took place following seven years of fallow when the swidden fields were being cleared for cultivation, primarily for cassava and corn.

The muré ceremony was maintained up until the 1930s, but then ceased due to the upheavals of the Japanese occupation during the Second World War. A shorter version of the rain dance was revitalised in the early 1960s at the behest of local government officials. However, one report claims that after the muré dance was performed at the court of President Soekarno in about 1963, Nggela was struck by a disastrous famine. The mosa laki responded by performing rituals and sacrificing a buffalo, sprinkling its blood into every corner of the village. For the following two decades, the community was reluctant to perform their sacred dances out of context.

By the 1980s these fears seem to have subsided. The muré dance was performed in 1987 for the visit of the district governor, and again in 1988 for a visit of the provincial tourist authorities.

Above: Women performing the muré dance in Nggela in 1988 wearing modern lawo butu and lawo kéli mara. Image courtesy of Cendana News. Below: Another image of the dance courtesy of Agus Mana.

To perform the muré dance in modern times, the young women wear a lawo butu over the top of a longer lawo kéli mara, along with gold earrings and necklaces. They wear ivory bracelets on both hands, although these are sometimes substituted with wooden copies, and dress their hair in the form of a bun. The dancers hold each other's hands with their bodies tilted back and walk around a circle marked out with ashes on the ground around the pusé nua, the sacred village centre. As the women dance, they sing traditional songs, assisted by one or two mosa laki.

Two dancers on the outside hold a piece of wood decorated with buffalo tails and continue to wave it while hissing during the dance.

To see a video of the muré dance, please click here.

Return to Top

Scholarship

Fabiola Triandita Alentyastr Kerong is a young architect who is a permanent assistant lecturer in the Department of Architecture at Flores University in Ende on the island of Flores. She obtained her first degree in 2009 at Malang National Institute of Technology in Malang, East Java, and her master’s degree in 2014 at Udayana Univesity in Badung, Bali. Her master’s thesis covered the structure of kampong Nggela.

Fabiola T. A. Kerong

Willemijn de Jong was born in Holland and is a retired Associate Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Zurich. She lived with the coastal Lio intermittently between 1987 and 2003, studying their rituals, changing social structure and textile material culture. She still visits the region regularly and in 2017 curated an exhibition at the Museum der Kulturen, Basel, entitled Striking Patterns: Global Traces in Local Ikat Fashion, which included examples from her collection of about 200 Lio textiles.

Professor Willemijn de Jong

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon 1990. Kecamatan Wolojita Dalam Angka 1990, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kabupaten Ende, Ende.

Aoki, Eriko, 2006. The Case of the Purloined Statues: The Power of Words among the Lionese, To Speak in Pairs: Essays on the Ritual Languages of Eastern Indonesia, pp. 202-228 and 317-318, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Badriantoro, Furqon, 2020. Kema Sa’o Nggua Nua Nggela: Rekam Proses Pembangunan Rumah Adat Kampung Nggela, Ende, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Seminar Karya & Pameran Arsitektur Indonesia (Sakapari), Universitas Islam Indonesia, Yogyakarta.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1994a. Cloth Production and Change in a Lio Village, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, Hamilton, Roy (ed.), pp. 211–227, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1994b. Cloth as Marriage Gifts: Change in Exchange among the Lio of Flores, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1044.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1995. Cloth as Marriage Gifts. Change in Exchange Among the Lio of Flores, Contact, Crossover, Continuity. Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America 1994,pp. 169–180, Textile Society of America, Los Angeles.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1997. Heirloom and Hierarchy. The Sacred Lawo Butu Cloth of the Lio of Central Flores, Sacred and Ceremonial Textiles. Proceedings of the Fifth Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, Chicago 1996, pp. 168–177, TSA, Austin, TX.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1998. Vom Brautpreis zur Mitgift? Heiratstransaktionen in Ostindonesien, Asiatische Studien, vol. 52, pp. 445–471.

de Jong, Willemijn, 1998. Geschlechtersymmetrie in einer Brautpreisge sellschaft. Die Stoffproduzentinnen der Lio in Indonesien, Reimer Verlag, Berlin.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2000. Women’s Networks in Cloth Production and Exchange in Flores, Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, Koning, Juliette; Nolten, Marleen; Rodenburg, Janet; and Saptari, Ratna (eds),pp. 264–280, Curzon, Richmond, Surrey.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2007. Rice Rituals, Kinship Identities and Ethnicity in Central Flores, Kinship and Food in South East Asia, Janowski, Monica, and Kerlogue, Fiona, (eds), pp. 196–222, NIAS Press, Copenhagen.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2011. Kleidung als Kunst: Porträt einer lkatdesignerin in Ostindonesien, Stoffe weben Geschichten: textile Kunstmaterialien im transkulturellen Vergleich, vol. 52, pp. 55–71, Jonas Verlag, Marburg.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2013. Women’s Networks in Cloth Production and Exchange in Flores, Women and Households in Indonesia, pp. 264-298, Routledge, London and New York.

de Jong, Willemijn, 2015. Luka, Lawo, Ngawu. Kekayaan Kain Tenunan dan Belis di Wilayah Lio, Flores Tengah. Maumere: Penerbit Ledalero. (Translation in Bahasa Indonesia of the ethnography of the book publication Geschlechtersymmetrie in einer Brautpreisgesellschaft. Die Stoffproduzentinnen der Lio in Indonesien. Berlin: Reimer Verlag, 1998, with a new introduction and conclusion)

de Jong, Willemijn, 2020. Ikat Patterns in Flores, Indonesia, and the Global Fashion Trajectory, Fashionable Traditions: Asian Handmade Textiles in Motion, edited by Ayami Nakatani, pp. 19-40, Lexington Books, Lanham.

Dietrich, Stefan. 1989. Kolonialismus und Mission auf Flores (ca. 1900-1942), Klaus Renner Verlag, Hohenschäftlarn.

Elias, Alexander, 2018. Lio and the Central Flores languages, Master’s Thesis, Leiden University.

Elias, Alexander, 2020. Are the Central Flores languages really typologically unusual?, Austronesian Undressed: How and why languages become isolating, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

Halim, Rahmatia A., 2016. Analysis homonimi dalam Bahasa Ende-Lio di daerah Flores NTT: Sebuah kajian semantik dan hubungannya dengan pembelajaran Bahasa Indonesia di SMP, Undergraduate Thesis, Mataram University.

Hamilton, Roy W., 1994. Ende Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, Roy W. Hamilton (ed.), pp. 121–147, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Howell, Signe, 1989. Of Persons and Things: Exchange and Valuables among the Lio of Eastern Indonesia, Man, vol. 24, issue 3, pp. 419–438.

Howell, Signe, 1990. Husband/wife or brother/sister as the key relationship in Lio Kinship and Sociosymbolic relations, Ethnos, vol. 55, issue 3–4, pp. 248–259.

Howell, Signe, 1996. A Life for ‘Life’: Blood and Other Life-promoting Substances in Northern Lio Moral Discourse, For the Sake of Our Future: Sacrificing in Eastern Indonesia, pp. 92-109, Research School CNWS, Leiden.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., 2015. Relasi struktur masyarakat dan tata zonasi permukiman adat di desa Nggela, Ende-Flores, ATRIUM, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 75-92.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., 2016. Struktur Organisasi dan Tata Zonasi Permukiman Adat di Desa Nggela, RUANG: Jurnal Lingkungan Binaan, vol, 3, no. 2, pp. 157-172, Denpasar.

Kerong, Fabiola T. A., and Siso, Silvester M., 2019. Pengaruh perilaku masyarakat terhadap pola permukiman adat di desa Nggela, Kabupaten Ende, RUANG: Jurnal Lingkungan Binaan, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 201- 212, Denpasar.

Lalo, Yohanes, 2009. Kecamatan Wolojita Dalam Angka 2009, Badan Pusat Statistik, Kabupaten Ende, Ende.

Mbete, Aron Meko, 1985. Keragaman Pemakaian Bahasa Lio, Linguistik Indonesia, vol. 3, pp. 29-35.

McWhorter, John. 2019. The Radically Isolating Languages of Flores: A Challenge to Diachronic Theory, Journal of Historical Linguistics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 177-207.

Mochdar, Dian Fitriawati, 2015. Identifikasi Pola Permukiman Tradisional Suku Lio, Dusun Nuaone Kecamatan Kelimutu Kabupaten Ende, Teknosiar, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 20-28.

Muda, Lambert, 2018 and 2019. Personal communications in Nggela.

Pak Martinus, 2024. Personal communication, Nggela.

Paru, Maria Alfionita; Sasongko, Ibnu, and Imaduddina, Annisaa Hammidah, 2018. Pola Organisasi Spasial Permukiman di Kampung Adat Nggela, Kecamatan Wolojita, Kabupaten Ende, Thesis, Institut Teknologi Nasional, Malang, East Java.

Prioharyono, J. Emmed M., 2012. Kekuasaan Politik dan Adat Para Mosalaki di Desa Nggela dan Tenda, Kabupaten Ende, Flores, Antropologi Indonesia, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 180-202.

Sado, Patrisius; Wulandari, Yunita; and Wahjutami, Erlina Laksmiani, 2021. Kajian Sa’o Tua sebagai Rumah Tinggal Suku Ende-Lio di Flores yang Tanggap Iklim, Seminar Nasional Teknologi Fakultas Teknik, University of Merdeka, Malang.

Saudale, Christofel Daniel, 2021. Arsitektur Ende Lio Kampung Adat Nggela – Ende – Nusa Tenggara Timur

Seran, Sixtus Tey, et al., 2005. Upacara Joka Ju (Tolak Bala) di Kelurahan Wolojita - Kecamatan Wolojita Kabupaten Ende, Dinas Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Unit Pelaksana Teknis Dinas (UPTD) Arkeologi, Kajian Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional Propinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur, Kupang.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2007. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1942: A Documented History, vol. 2, Brill, Leiden.

Sugishima, Takashi, 1994. Double Descent, Alliance and Botanical Metaphors among the Lionese of Central Flores, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 150, issue 1, pp. 146–170.

Sunimbar, Natalia Adel H. N. Mari, 2020. Integrasi Nilai-Nilai Kearifan Lokal Joka’ju Masyarakat Nggela dalam Membangun Karakter Sadar Bencana Siswa di Sekolah Menengah Atas, Jurnal Geoedusains, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 62-71.

Van Suchtelen, Bertho Charles Constant Margarethe Marie, 1921. Endeh, Mededeelingen van het Bureau voor de Bestuurszaken der Buiten-bezetting, Bewerkt door het Encyclopaedisch Bureau (Afleverin XXVI), N.V. Uitgev. -Mij. "Papyrus", Weltevreden.

Vries, J. J. de, 1910. Residentie Timor en Onderhoorigheden, Onderafdeeling Endeh, Nota van Bestuursovergave.

Weber, Max, 1890. Ethnographische Notizen über Flores und Celebes, Verlag von P. W. M. Trap, Leiden.

Yamaguchi, Masao, 1989. Nai Kéu, a ritual of the Lio of Central Flores, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Rituals and Socio-Cosmic Order in Eastern Indonesian Societies, part 1, Nusa Tenggara Timur, vol. 145, no: 4, pp. 478-489, Leiden.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 8 February 2024.