Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Geography

The Indigenous Population of Mingar

The Immigrant Population of Mingar

Ethnography

The Findings of Robert and Ruth Barnes

The Indigenous Textiles of Mingar

Textiles Imported to Mingar

Weaving Among the Immigrant Communities

Bibliography

Geography

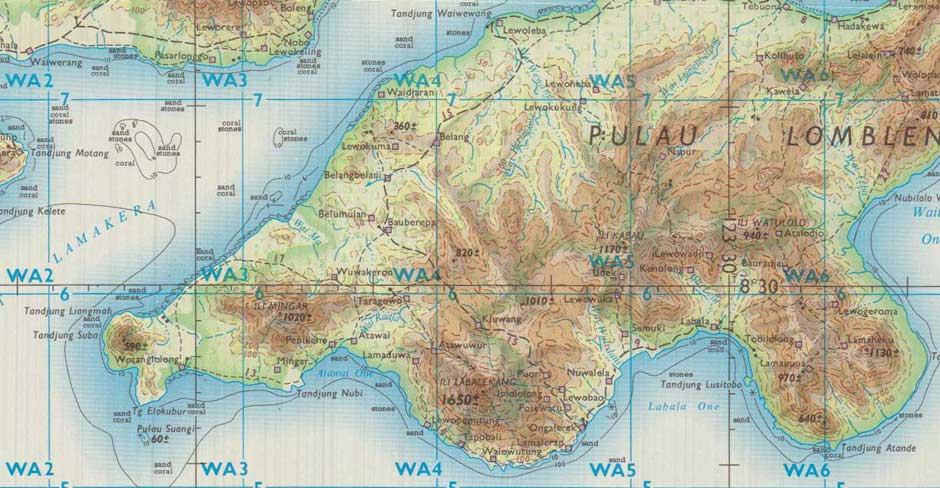

The Mingar Peninsula lies at the extreme western tip of Lembata Island and terminates at Cape Naga. Local people call it the Naga Peninsula. To the north, the foot of the active volcano of Ilé Boleng and the southeast coast of Adonara Island are a mere 4.5km distant, while the western tip of Timor Island is directly due south. To the west the Lamakera Strait separates the Mingar Peninsula from Solor Island.

Mingar as depicted on a UK map of 1970

Director of Military Survey, Ministry of Defence, UK

The region is wild, rugged, heavily forested and overlooked by the mount of Ilé Mingar, the remnant of an ancient volcano with its altitude reported as either 969m or 1020m. Ilé Mingar is located just 12km west of the dormant volcanic crater of much larger Ilé Labalekang (1643m), which has the whaling village of Lamalera located at its southern foot.

Looking eastwards down the Mingar Peninsula

The heavily forested slopes of Ilé Mingar

The sheltered north coast of the Mingar Peninsula is relatively calm, with long stretches of sandy beach mostly protected by coral reefs. Lekang, Cypress and Green turtles nest on the beach at Rian Bao, just south of Loang, while freshwater crocodiles lurk in the river estuaries.

By contrast the mainly rock-strewn southern coast around Atawai Bay is more dangerous, being fully exposed to the Savu Sea. To the west of Atawai is the spectacular 5km-long white sandy beach, known as Pasir Putih (White Sand). It stretches from Desa Mingar, positioned directly south of Ilé Mingar, to beyond Wotanglolong. As the beach is the main tourist attraction on the Mingar Peninsula, the village of Mingar has been recently renamed Desa Pasir Putih.

The rocky coastline of Atawai Bay, looking west towards Tewaowutung

Pasir Putih or White Beach, Mingar, looking west towards Wotanglolong.

Tiny Pulau Suangi lies just offshore

The rugged coastline around the foot of Ilé Labalekang, stretching from Lewopunutung to Topobali with Lamalera beyond

Following the reorganisation of local government in 1962, most of the Mingar Peninsula now falls into the new administrative district of Kecamatan Nagawutung (Dragon Point, wutung meaning edge or end), with its administrative centre based in the new settlement of Loang. Nagawutung encompasses the western tip of Lembata and the western half of Ilé Labalekang. It has eighteen desa and had a total population of 9,138 in 2015 (Kabupaten Lembata Dalam Angka 2016). Many of the villages are quite small, the population of Mingar being 1,074, Penikenek (sometimes Penikene) 705 and Lusiduawutun 539 (2010 census).

Catholic Parish Church of Santa Maria, Mingar

A Dutch map of 1931 shows that at that time there was an unpaved roadway leading from Lewoleba two-thirds of the way to Lamalera, the remaining third being a horse trail. A second horse trail from this roadway linked to a horse trail that circumnavigated the foot of Ilé Mingar, passing by both Mingar and Penikenek. A separate horse trail continued southwards to Lewopenutung.

Mingar as shown on the Topographic Reconnaissance Map of Onderafdeeling East Flores

and the Solor Islands, Batavia, 1931

Today Mingar is most easily accessed by the coastal road that runs from Lewoleba to Lamalera. Following almost twenty years of neglect, by 2016 the state of this road had become terrible. Now sections of the road between Lewoleba and Mingar are being slowly upgraded, although the stretch from Mingar to Lewopenutung, Topobali and Lamalera remains in very poor condition. Loang and Idalolong can also be accessed via poor quality link roads from the main Lewoleba to Lamalera highway.

Return to Top

The Indigenous Population of Mingar

The Mingar Peninsula is home to a range of different communities, some indigenous, some who are immigrants from other parts of Lembata and a few who are Lamaholot immigrants from East Flores.

The main indigenous community live in the three south-coast villages of Mingar (Pasir Putih), Penikenek and Lewopenutung. According to the residents of these villages, their ancestors originated from the village of Lewopenuto, which was located at an elevated position on the western flank of Ilé Labalekang. They eventually moved down from the mountain to establish settlements on or near the coast. Some moved down to found a new village with a similar name, Lewopenutung, in Atawai Bay. Others continued further west to establish the village of Wuakerong, close to Loang on the north coast of Nagawutung. While there is no folk memory of when this happened, it must have been prior to 1910 because Lewopenutung and neighbouring Watuwatung were already established when Dutch troops arrived under the command of Captain Beckering. Mingar, Penikenek and Lewopenutung all appear on the 1931 Dutch map of Onderafdeeling East Flores and the Solor Islands.

Lewopenutung today

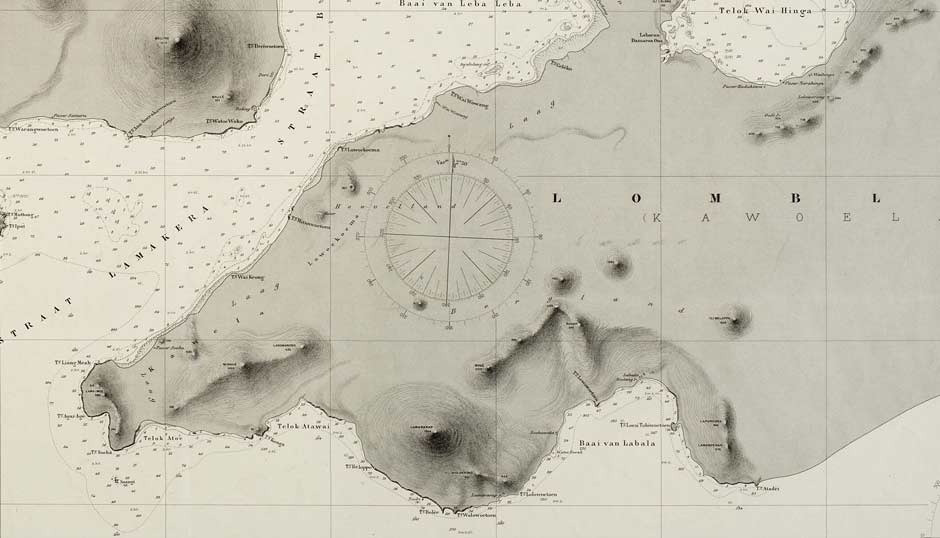

In 1910 Captain J. D. H. Beckering arrived on the island from Kupang with a company of troops tasked with imposing direct Dutch control, registering the population and confiscating their weapons. He most likely had access to the hydrographic survey conducted by the survey vessel Hr.Ms. Opnemingsvaartuig van Doorn between 1908 and 1909 – see below. A few islanders attempted to confront the Dutch invaders, but without success. Ike Buang, a local resistance fighter who was killed opposing the Dutch, is buried at Wologolok to the east of Lewopenutung (Aster Wathun 2001, 50).

Beckering was surprised to find that most of the island’s population lived in easily defendable sites on the slopes of the four highest mountains: Ilé Uyelewun (Kédang), Ilé Lewotolo (Ilé Api), Ilé Labalekang and Ilé Mingar, as well as on the Ata Déi plateau and the mountains of Lewoleba (Beckering 1911, 189). There were only a few villages situated around the coast, such as Lamalera, Labala and Kalikur.

Beckering commented that the villages of Warawatung and Lewopenutung 'located in an enclave on the southwestern slope of Labalekan' could only be reached after crossing some deep ravines (1911, 193). These villages and their paths and gardens were littered with stones.

Mingar from a Nautical Chart of Lomblen, dated 1911

(Hydrographic Department of the Naval Ministry, The Hague, June 1911)

The Dutch initially administered the island from Hadakewa in the haven of Waienga Bay, far removed from Mingar. In 1920 they began constructing an unpaved road along the north coast of Lembata, which was not completed until 1935 (Barnes 1996, 49). However it was unusable by cars or trucks because flash floods repeatedly destroyed the bridges. The south on the other hand remained completely untamed, only partly accessible on horseback. Many of the trails were almost impassable to horses, requiring constant jumping from boulder to boulder (van den Windt 1936, 77, cited by Barnes 1996, 49). During this period the Dutch began to encourage tribal chiefs to relocate their villages from the mountainsides down to the coast. One of the first was Lewokewe, which was forcibly moved down to the coast by Beckering who renamed it Lewoleba (Barnes 1996, 21). It subsequently became the capital of the island.

The Dutch presence on Lembata was short-lived – the island had little to offer the colonial authorities. Prior to the establishment of direct Dutch control, most districts of Lembata were subject to either the Catholic Raja of Larantuka or the Muslim Raja of Adonara, based at Sagu on the north coast of the island (Barnes 1986, 300). The former ruled over the Demon mountain people in the hinterland of Lembata as well as Lewolein and Lamalera, while the latter ruled over the Paji coastal peoples in Lewotolo (Ilé Api), Kédang, Labala and Mingar. In 1929 and 1931 the Dutch withdrew, consolidated all of their Lamaholot territories back under the authority of the Rajas of Larantuka and Adonara. Thus both Mingar and Lewopenutung became nominally subject to the rule of the Raja of Adonara (Barnes 1993, 29 and 30). The Raja's deputy or kakang for southern Lembata was based at nearby Lamalera, a position that was held until the Indonesian reorganisation of local government in 1962 (Ruth Barnes 1989, 5).

The Societas Verbi Divini (SVD) initially established a presence on Lembata in 1920, with the arrival of the German Catholic missionary Bernadus Bode in Lamalera. Sometime later the SVD created a small mission station at Lewopenutung (Yayasan Hidup Katolik 1992, 47).

A quiet side street in Penikenek

According to village residents, in the past Penikenek was only a small settlement and even in 1984 it had only a handful of houses. By contrast, neighbouring Lewopenutung had expanded to such an extent that there was less and less land available to provide space for the private gardens of expanding families. Consequently in 1987 a number of households relocated from Lewopenutung to Penikenek. Other families from Lewopenutung and Wuakerong soon followed, creating the current two dusuns.

Return to Top

The Immigrant Population of Mingar

The Mingar Peninsula is home to many immigrant communities that have relocated there from other parts of Lembata such as Ilé Api, Ata Déi and Bakan. It also has a few communities that originate from further afield.

The first main settlement south of Lewoleba on the north coast is Waijaran. It has a fishing community of Bajau Laut who migrated from Meko/Mökko on the northeast coast of Adonara after the Dutch attacked and disrupted it, possibly during the 1930s (Barnes 1974, 19).

Loang is a relatively new village established by the Lembata Regency in the 1970s. In 1978 the local government made attempts to settle the populations of several villages on Ata Déi that had been affected by the 1976 earthquake and landslide (Barnes 1996, 8). However the project was never completed. In the meantime the collapse of Ilé Belopor on Ata Déi in 1979 and the resulting tsunami that destroyed Waiteba created an urgent need to relocate even more people. In 1980 the national government in Jakarta decided to transfer the capital of Nagawutung from Boto to Loang and to relocate more people from Ata Déi. As the village has grown it has been divided into Desa Duawutun, Desa Ria Bao and Desa Wuakerong. The surrounding area is agriculturally important, the main crops being corn and cashews. Other crops include rice, peanuts, soybeans, green beans and cassava as well as teak, mahogany, coconut, and sandalwood.

The much older village of Babokerong (Baupukang) at the western end of the north coast was founded by people from Ilé Api in the nineteenth century, who relocated because of a local dispute or conflict. Baobolak was established more recently as a satellite village.

Lolong (also known as Lewobelolong) was only established in 2000 as a result of the expansion of Mingar (Pasir Putih). Although it only has 300 inhabitants it has its own clan house containing the skull of the ancestor of the Atapune clan.

The government built Tewaowutung as a transmigration camp for displaced villagers following the 1979 Ata Déi tsunami. It too has a population of around 300, mostly belonging to the Atawua clan.

Finally Lewopenutung is home to a number of immigrant families belonging to suku Lamak Rajan and suku Piring Besar who relocated from Bakan on the slopes of Ilé Kerbau in central Lembata.

Return to Top

Ethnography

The indigenous community of Mingar consider themselves as ethnically different from the people living on the east side of Ilé Labalekang, including the villages of Lamalera, and have a quite different clan structure. They speak dialects that are classified as Central Lamaholot, including bahasa Mingar and bahasa Lewopenutung (Melalatoa 1995, 442).

In terms of religion, for Nagawutung as a whole 86.3% of the population is Catholic and 13.6% is Muslim (Kabupaten Lembata Dalam Angka 2014). There are currently 11 Catholic churches and 3 mosques.

Sue talking to the ladies of Lewopenutung

If we take the village of Penikenek as an example, it contains two communities – one from Lewopenutung and the other from Wuakerong. Apart from two Muslim families the people are predominantly Catholic. The clan system is typically Lamaholot, with children born into the clan or suku of their father. These clans were traditionally strictly exogamous, but are less so today. The two original ‘lord of the land’ clans who hold land rights are Lewo Pao Ata Ura and Lewo Kapi Wato Bolak. The clans that arrived later are Lebao, Lemanuk, Lebuan, Ata Wuwur, Blitin, Meluwitin and Imulolong. The village does not only own the land around the village, but also has distant land holdings further east. Villagers practise slash and burn agriculture, planting corn, hill rice, coffee and beans.

New slash and burn plots in the shadow of Ilé Mingar

In Mingar the two ‘lord of the land’ clans are Kabelen and Ketupapa or Ketepapa. In addition there are eleven supporting clans.

Marriage alliances are asymmetric and circular. For example in Penikenek, boys from Lewo Pao Ata Ura marry girls from Ata Wuwur; boys from Ata Wuwur marry girls from Lebuan and boys from Lebuan marry girls from Lewo Pao Ata Ura.

Bridewealth in Penikenek consists of an elephant tusk or its monetary equivalent. The counter-prestation consists of either a two-panel or a three-panel sarong and five ivory bracelets. To accompany a two-panel sarong, the bracelets must have a smooth outer side, but to accompany a three-panel sarong, the bracelets must be carved with an outer ridge. Obviously a counter-prestation of a three-panel sarong has a higher value than that of a two-panel sarong. Sarongs used for bridewealth are owned by the clan and must have a circular warp with an uncut section of unwoven warps, known as the revot (pronounced ‘refot’).

In Lewopenutung bridewealth consists of an elephant tusk or the equivalent in money. The counter-prestation consists of three three-panel sarongs and fifteen bracelets. However they do not weave a 3-panel sarong here. It does not matter if the sarongs come from Ata Dei or elsewhere. The value of a 2-panel sarong is lower.

The villages along this coast participate in the annual Guti Nale festival held every February at the height of the rainy season on the beach at Mingar during full moon. The ritual revolves around an annual natural event when edible sea worms belonging to the species Eunicid or Lycidice, known locally as nale, begin their reproductive cycle. During the night the worms detach themselves from the underwater rocks and release their brightly coloured sexual parts from the front of their bodies, which rise to the surface to shed their eggs and sperm, turning the surface of the sea into a writhing mass of spaghetti. The timing of the swarming is closely linked to the lunar cycle. The quantity of worms supposedly indicates the size of the following rice harvest as well as the future wellbeing of the local people.

Villagers in traditional attire for the Guti Nale festival, Mingar

(Image courtesy of Nansianus Taris, KOMPAS.com 2019)

The fertility ritual is organised by the two ‘lord of the land’ clans, Kabelen and Ketupapa and begins with the clan leaders making offerings and ritually feeding the ancestors. Once observers on the beach see that the nale are spawning, they light palm leaf torches and people flock to the beach, scooping up the nale in specially made baskets. The sea worms are considered a gastronomic delicacy.

Return to Top

The Findings of Robert and Ruth Barnes

The Oxford anthropology research student Robert Barnes and his wife Ruth initially spent eighteen months on Lembata, from October 1969 until June 1971 (Barnes 1988). They stayed at Leuwayang in the then remote region of Kédang while he conducted fieldwork for his 1972 D. Phil. thesis. Having made a brief one-week visit to Lamalera in 1970, he returned with his wife Ruth in July 1979 to spend three months studying its subsistence economy. In July 1982 Robert and Ruth Barnes returned to Lamalera for a longer six-month assignment, Dr Robert Barnes completing his research into the village’s anthropology and fishing economy and Ruth Barnes studying the local weaving for her 1984 Oxford University D. Phil., which was later published in 1989 as The Ikat Textiles of Lamalera. Dr Robert Barnes returned to Lamalera in June 1987 for a three-week project assisting Granada Television to shoot a documentary.

In her thesis, Ruth Barnes provides various insights into the Mingar region and its textiles. In short she stated that weaving in Mingar was traditionally prohibited and all textiles, both for everyday wear and for adat ceremonies or for bridewealth, were obtained from the weavers of Lamalera through a defined system of barter.

Rather than précis her various comments, we think the clearest picture can be gained by quoting them verbatim:

On Lembata, there are two regions where weaving is traditionally prohibited. These are the Mingar and Kedang districts (Ruth Barnes 1984, 120).Lamalera has traditionally supplied all the local cloth needed in Mingar (Ruth Barnes 1984, 9).

Judging by conversations I have had with the women of Lamalera, the situation in Mingar is similar [to that in Kédang]. No cotton is grown there, and until quite recently, i.e., well within living memory, no weaving was done in this area at all. The people of Mingar depend entirely on the cloth production of Lamalera, both for clothing and for their bridewealth cloth. Now some weaving is done in Mingar, as well, but there is still a very good market for cloth coming from elsewhere (Ruth Barnes 1984, 120 to 121).

The women of Lamalera are entirely responsible for bringing the staple foods, maize, rice, and tubers, into the village. They take the dried fish or their cloths into the mountains and barter for the necessary goods. Fish takes first place in their transactions, because there is a wider and more consistent market for it, and because it is available to all households which maintain a connection with the fishery. The cloth trade, however, holds a very important second place which can become of life-saving significance when the catch is very low (Ruth Barnes 1984, 121).

Then the women will take their woven goods and go for long excursions which may take them away from the village for several days at a time. Over generations the women have established their trading connections, and they will visit villages where they are well known and can expect willing trade partners. In the Mingar region possible goals are Waupukan, Hatablan, Wauhija, Tewau Wutu, and Peni Keni (Ruth Barnes 1984, 122).

The cloths made in the village are not woven on commission, but are taken along on a bartering excursion in a hope that a buyer will be found. The two areas suitable for the trade, Mingar and the villages around the Labalekang volcano, have different preferences. In Mingar, people like sarongs which are made from local cotton and dyed with natural dyes. They praise the durability of the indigenous Lamalera cloth, which stand up to daily wear far better, they claim, than machine-produced fabrics. Of course Mingar, because of its prohibition on weaving, gets all locally made cloth from Lamalera, both for every-day work and for festive wear (Ruth Barnes 1984, 125).

All bridewealth cloth used in Mingar, and often that used in the Labalekang mountain villages, as well, comes originally from Lamalera (Ruth Barnes 1984, 127-128).

The value of locally woven cloth, in exchange for goods, is as follows. I have also included the cash value of each cloth, as of 1979 and 1982 (Ruth Barnes 1984, 57):

Type of Cloth

Value in kind

Value in Rp.

1979

1982

1

Men’s sarong

1,000 ears of maize

7,500

10,000

2

Woman’s ordinary sarong

5 blek of (un-husked rice)

7,500

10,000

3

Woman’s festive sarong

up to 10 blek of rice

15,000

20,000

4

Two-panel adat cloth

20 blek of rice

20,000

40,000

5

Three-panel adat cloth

30 blek of rice

30,000

60,000

6

Shoulder cloth

5,000

7,000

Note: a blek is a large 20 litre storage container

Robert Barnes later echoed the views of his wife:

The women in most of the mountain villages [of Lembata] knew how to weave except in Kédang, where it was prohibited. In fact, Mingar, in south-west Lembata, also did not weave (Robert Barnes 1996, 135).

Return to Top

The Indigenous Textiles of Mingar

From our discussions with local villagers it is clear that the Barnes’s conclusions are partly correct. Many textiles were, and still are, imported into the Mingar region from the villages on the southern promontory of Ilé Labalekang - Tapobali, Wolowatung, Lamalera and the villages above Lamalera – and also from further afield locations on Ata Déi, and even from Kalikasa.

However it is also obvious that there has been a long-established indigenous weaving culture centred on Lewopenutung, Penikenek and, to a lesser extent, Mingar that has so far been overlooked.

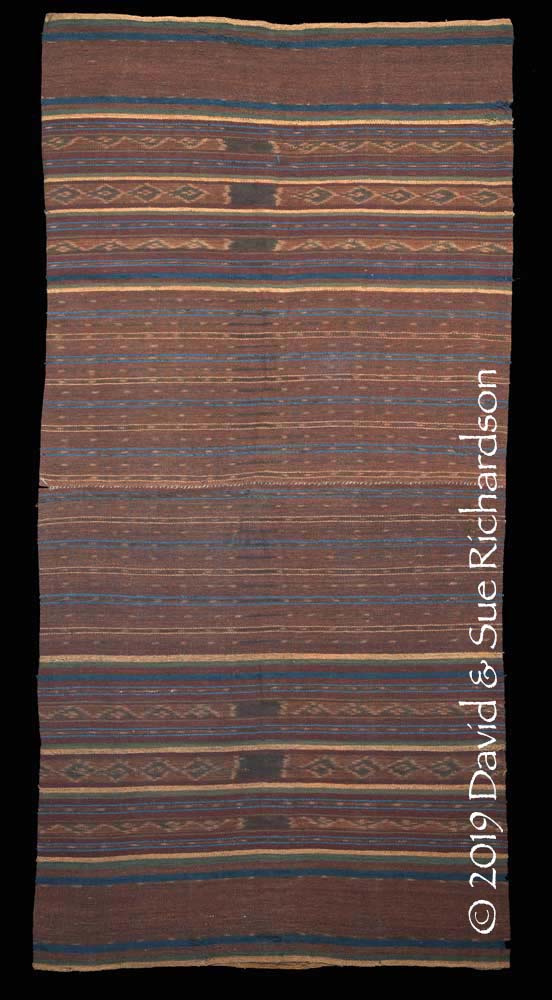

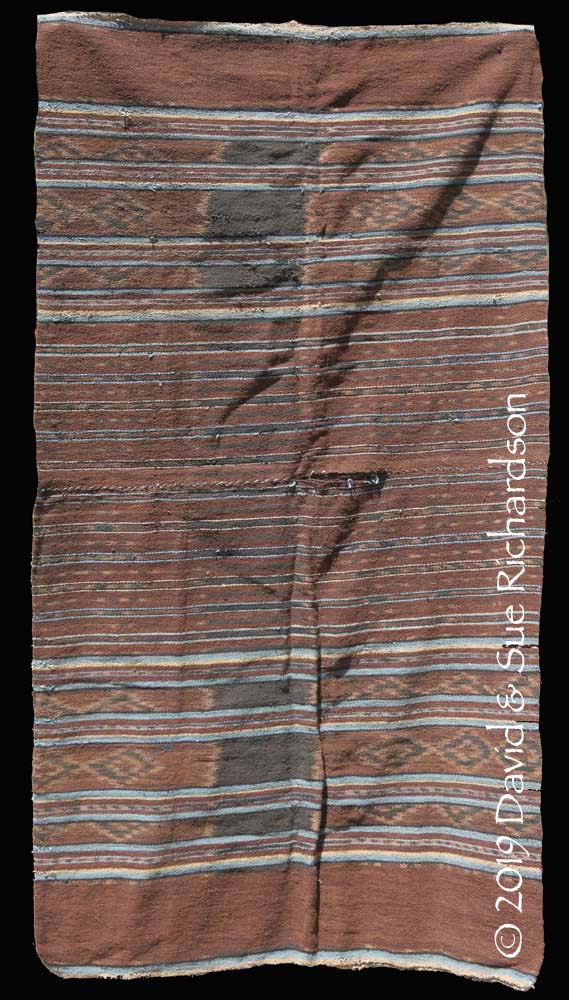

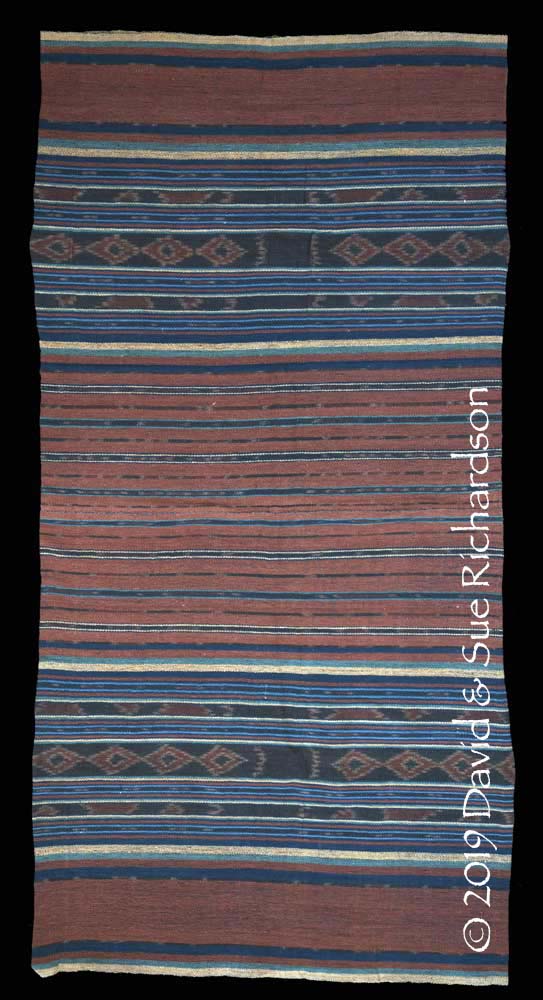

These local Mingar textiles have a simple yet distinct regional style, which has no resemblance to any other textiles produced on Lembata Island. They have an overall earthy brown tone with bands of ikat decorated with rows of diamond motifs, known as ruit, the Dutch word for diamond, and zigzags, referred to as kera belapit or coconut leaf. Those that are used for bridewealth must belong to the clan of the wife-givers, and must have a continuous circular uncut warp. The short section of unwoven warps is called the revot (pronounced ‘refot’) or alternatively the serewot.

The residents of the indigenous weaving villages refer to a woman’s sarong as a kewatek, pronounced ‘kwa’tek’, although some use the alternative terms kreot or kreot kiwan, the Lamaholot term kiwan meaning interior or mountain but used in this case to indicate local or indigenous. In the local dialects a two-panel sarong is a kewatek nai juah and a three-panel sarong is a kewatek nai telon. The former has less value than the latter. From what we have seen, these local villages only produce two-panel kewatek nai juah. All of their kewatek nai telon appear to be imported.

Contrary to what has been published, cotton does grow in this area, although there is less available today than there was in the past because villagers are no longer planting their cottonseeds. It is interesting that all of the older locally woven textiles are made from hand-spun yarn. Indigo and morinda also thrive along this southern rocky coastline. Local dyers use morinda without the addition of lime powder or ash water and produce warm tones of brown - unlike the rusty browns found in Lamalera. A medium brown colour is achieved through three separate immersions in the morinda dye bath, while lighter browns are dyed twice. To get a redder brown they first dye with morinda, then indigo, and then morinda again.

Direct evidence of indigenous local weaving comes from two sources – directly from the experience of local women who are still weaving today, and from the provenance of some of the older cloths.

For example the local weaver Fransiska Kewa Lebao, who lives in Penikenek, was born in 1951 and belongs to a family where all of the women are weavers. They were each taught to weave by their mothers and grandmothers. Fransiska’s grandmother was most probably born between 1900 and 1910, so would have been weaving before or well before 1930. The family are unaware of any past restrictions on weaving in their village.

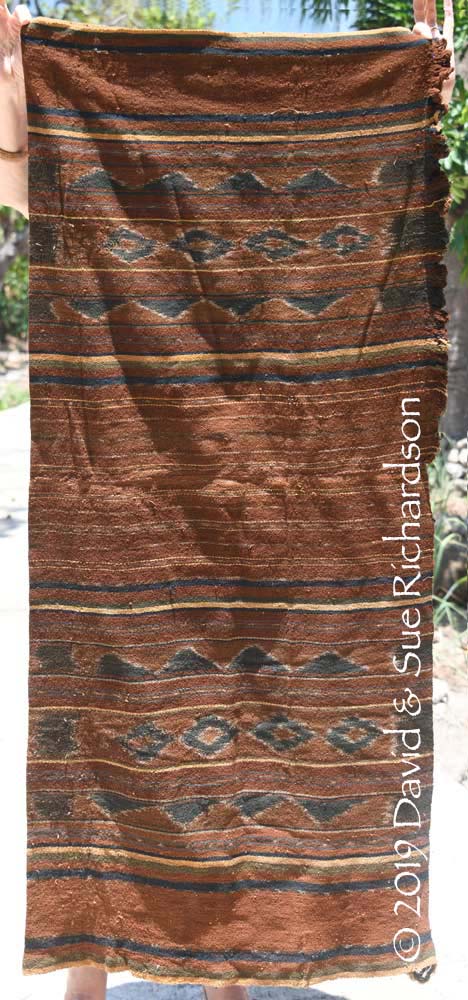

Regarding the older textiles, a two-panel kewatek sarong in our collection from Lewopenutung is around 100 years old. It was bound and woven from hand-spun cotton by Tuto Tobin, from suku Ofong, who was born in that village and married a local man from suku Labao. She died about 60 years ago when she was very old and could only walk on her arms and legs. Her relatives think that at the time she may have been almost 100 years old. We acquired the kewatek directly from one of her grandsons, aged 68, who formerly lived in Lewopenutung but now lives in Penikenek.

The kewatek nai juah woven by Tuto Tobin in Lewopenutung roughly a century ago

Richardson Collection

Another kewatek nai juah woven by Tuto Tobin in Lewopenutung at roughly the same time

A second hand-spun two-panel kewatek in our collection was woven by Yusfina Osé Lebuan from suku Lebuan in dusun Mauraja, Lewopenutung. She is now aged around 80 and her eyesight is failing. She wove the kewatek about 40 to 50 years ago. We acquired it from her granddaughter.

A kewatek nai juah woven by Yusfina Osé Lebuan from suku Lebuan, Lewopenutung

Richardson Collection

There is a remarkable uniformity to this family of textiles, with the same central banding and the same simple ikat pattern repeated time and time again.

Above and below: two kewatek nai juah woven in Lewopenutung. Family heirlooms

A kewatek nai juah woven over 60 years ago by Beva in Lewopenutung. She died around 1965. The cloth is now owned by her 52-year-old granddaughter

Above and below: two different kewatek nai juah belonging to separate families living in Penikenek

Textiles with an identical layout are still being woven in Lewopenutung and Penikenek today, but using commercial yarn and synthetic dyes.

A back-tension loom set up on the veranda of a house in dusun Mauraja, Lewopenutung

A modern kewatek nai juah recently woven in Lewopenutung

There is also a strong weaving culture in tiny isolated Lusiduawutun, located inland 5km north of Lewopenutung. The village currently has three weaving groups producing textiles for sale using commercial yarns and dyes. Here the diamond and zigzag motifs are known as bfajak and kera blepit (Pukan 2016).

The weaving tradition in Mingar village does not appear to be anywhere as strong. According to a local legend, two of their distant ancestors, Ratu Gawi Oa and Peni Tapobali, arrived on Lembata from the island of Lepan Batan with a loom. These ancestors eventually abandoned their skills of weaving ikat in favour of adopting the skills of basket-weaving from Lamalera (Blikololong 2010, 121). As a result they began obtaining their textiles from Lamalera through a customary system of barter using a counting method based on monga, a monga referring to a small, defined number of items (Blikololong 2010, 145). In Mingar, Ilé Api and Hadekewa, one monga refers to ten items. Thus for example, ten corn cobs, ten bananas or ten sweet potatoes. In other places a monga is only five items.

According to Pius Demon Sura, the kepala desa in Mingar, there used to be a weaving cooperative in the village with ten women but it folded up in 2005.

Return to Top

Textiles Imported to Mingar

The most valued textile that can be included in a counter-prestation for a marriage alliance is a three-panel kewatek nai telon. However because local weavers only produce two-panel kewatek nai juah, all of their kewatek nai telon must be obtained from other regions of Lembata. The closest source of such sarongs is in the neighbouring villages at the southern tip of the Ilé Labalekang promontory – Topobali, Wolowatung, Lamalera, and the villages above Lamalera.

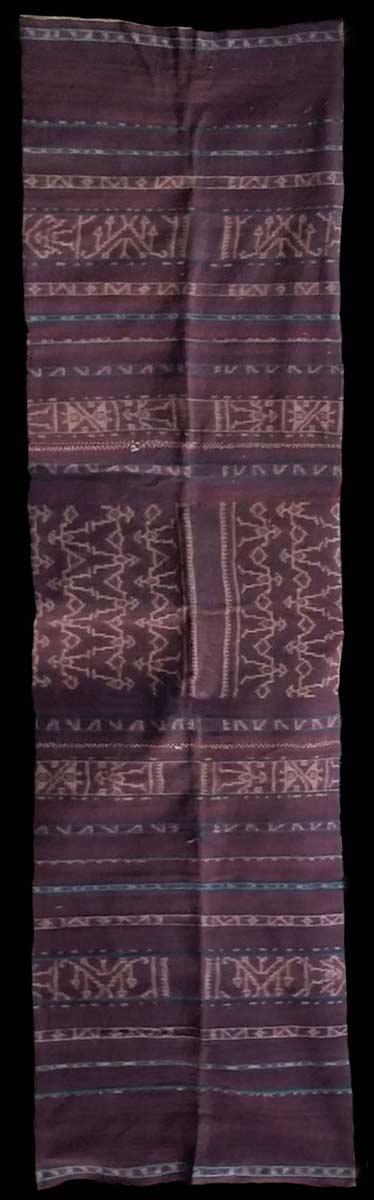

The first example of an imported textile is from Wolowatung on the southern tip of Lembata between Topobalai and Lamalera. It was described as a kreot by its owners, not a kewatek.

A kreot nai telon with an intact revot belonging to a family in Penikenek. Decorated with the taru mata (putting on the eyes) pattern, it was woven in Wolowatung

An unusual kewatek nai telon woven in one of the villages outside of Lamalera, owned by a family in Lewopenutung

Despite this abundant nearby source, several three-panel sarongs we have seen in Lewopenutung and Penikenek were imported from Ata Déi.

An unusual petak haren from Ata Déi owned by a family in Lewopenutung

Return to Top

Weaving Among the Immigrant Communities

Although the villages of Babokerong (Baupukang) and Baobolak were founded by families who originally came from Ilé Api, they no longer weave today.

Some of the women in Tewoawutung who were relocated from Ata Déi after the 1979 tsunami continue to weave in the Ata Déi style, although the quality of their binding is inferior to that found in their home region.

A petak harén with the dolo-dolo pattern woven in Tewoawutung around 2010

(Photographed in 2016 by John Ang)

We have not explored Loang.

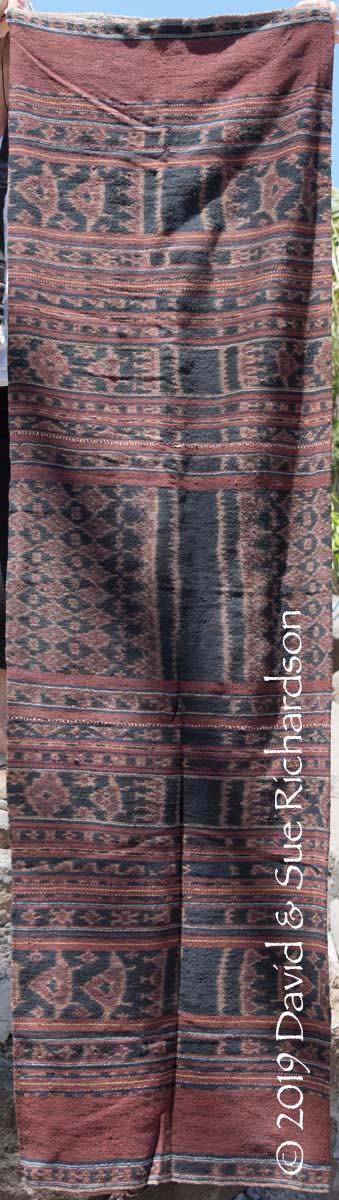

One of the most extraordinary textiles found in Mingar was produced by a family whose forefathers came from East Flores. Now in the Richardson Collection, it was described as a kreot nai telon kiwan and was woven by Maria Kewa Lebuan who belonged to suku Labuan and lived in Penikenek. She was born in around 1911, married Sira Labao, a farmer from suku Labao, and died in 2006. Maria had two children, one boy and one daughter named Fransiska. For Fransiska’s wedding, her husband’s suku provided bridewealth in the form of an elephant tusk. In response, Fransiska’s suku, Labao, made a counter-prestation, which included the sarong woven by Maria with its uncut revot.

The kreot nai telon kiwan woven in the hamlet of Penikenek about 85 years ago

Richardson Collection

Fransiska chose not to cut the revot so the kewatek remained clan property. Had she done so, the sarong would have become her property because it could no longer have been used for bridewealth exchange. However she had no need because she did not have a sister who might have required this sarong as a counter-prestation for her own marriage.

Fransiska and her daughter Arnolda with the kreot nai telon kiwan

Fransiska had four children – three sons and one daughter, Arnolda Tuto. When Arnolda was married in 2005, the very same sarong was given as part of the counter-prestation to her husband Tobius’ suku. After the marriage Arnolda was keen to keep the sarong as her property. She therefore cut the revot and sewed up the side seam. As such it was no longer clan property and could never be used for bridewealth again.

The kreot nai telon kiwan is remarkable for three reasons - it is three-panel, has a totally different layout from the indigenous Mingar kewatek and contains motifs from a number of different regions of Lembata:

- - tena chevron-shaped motifs, said to represent a boat but similar to the naga figures found on the tenépa of Lamagute (Atawatung), Ilé Api

- - mokun manta ray motifs similar to the moko motifs found in Lamalera and Ata Déi

- - tona eight-pointed stars, found occasionally in Ata Déi and other parts of the Lamaholot region

- - bajawa diamonds enclosing a cross, occasionally found in Ilé Api

Fransiska was clear that, unlike her neighbours, she belonged to a family that was not indigenous to Mingar. Her ancestors came from Ilé Mandiri on East Flores and after arriving on Lembata they settled on low-lying Awulolong Island, also known as Pulau Sipit (Snail Island), just offshore from Lewoleba. When the island was flooded they left and moved to Penikenek. Although we can find no historical record of a local flood, tsunamis are not uncommon in this region.

An Ilé Mandiri origin explains why the weaver’s patrilineal line was suku Lebuan, a clan from East Flores not Lembata. Perhaps Maria Kewa Lebuan gained her localised weaving skills because one of her male ancestors married a woman from Ilé Api or another important weaving centre on Lembata.

Interstingly there is a Lembata legend that says several tribal groups once lived on Awulolong Island. After it was destroyed by a tsunami some moved onto coastal locations on the mainland, while others migrated to Ilé Api and the Ilé Bolang region of Adonara (Ndoen 2017, 45; Lianurat 2019).

Return to Top

Bibliography

Aster Wathun, Nico Ch., 2001. Pariwisata Lembata, Department of Transportation and Tourism of Lembata, Lewoleba.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata 2015. Kabupatan Lembata dalam Angka 2014, Lewoleba.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata 2017. Kabupatan Lembata dalam Angka 2016, Lewoleba.

Barnes, Robert, 1988. Ethnography as a Career: Second Thoughts on Second Fieldwork in Indonesia, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, vol. 19, pp. 241-250.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1984. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera, Lembata, within the Context of Eastern Indonesian Fabric Traditions, D. Phil. Thesis, Lady Margaret Hall and Trinity College, Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989. 'The Bridewealth Cloth of Lamalera, Lembata', in To Speak With Cloth: Studies in Indonesian Textiles, Gittinger, Mattiebelle, (ed.), University of California, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 1991a. "Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 2, pp.95–112.

Barnes, Ruth, 1992. Textile Design in Southern Lembata: Tradition and Change, Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics, ed. Jeremy Coote, pp. 160–178, Clarendon Press Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1993. Change and Tradition in Lamaholot Textiles: The Ernst-Vatter-Collection in Historical Perspective, Weaving Patterns of Life: Indonesian Textiles Symposium 1991, Nabholz-Kartaschoff, Marie-Louise; Barnes, Ruth; and Stuart-Fox, David (eds.), Museum of Ethnography, Basel.

Barnes, Ruth, 2004a. Ostindonesien im 20. Jahrhundert: Auf den Spuren der Sammlung Ernst Vatter, Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt.

Barnes, Ruth, 2007. Recording Cultures: Collecting in Eastern Indonesia, Colonial Collections Revisited, Peter J. ter Keurs (ed.), pp. 203–219, CNWS Publications, Leiden.

Beckering, J. D. H., 1911. Beschrijving der eilanden Adonara en Lomblem, behoorende tot de Solor-Groep, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2e Série, vol. 28, pp. 167-202.

Blikololong, Jacobus Belida, 2010. Du-Hope di tengah penetrasi ekonomi uang sebuah kajian sosiologis terhadap sistem barter di Lamalere, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Doctoral Thesis, Universitas Indonesia, Depok.

Lianurat, Antonius Buga, (Antoni Lebuan), 2018 and 2019. Head of Culture, Lembata Culture and Tourism Office, Personal communication and translation.

Melalatoa, M. Junus, 1995. Ensiklopedi Suku Bangsa di Indonesia Jilid L-Z, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Ndoen, Jeremias, 2017. Pemanfaatan Lahan Berkelanjutan Berbasis Tata Nilai Lokal, (Utilization of Sustainable Land Based On Local Values), Thesis, Institut Pertanian Bogor, Bogor.

Kuya, Polykarpus, 2019. Chairman of the Lembata Guides' Association, Personal communication and translation.

Pukan, Bonne, 2016. Wanita Lusiduawutun Lembata Lebih Suka Menenun, nttsatu.com

Yayasan Hidup Katolik, 1992. Mingguan hidup, vol. 46, issues 34-43, Jakarta.

Publication

This webpage was first published on 8 December 2019.