Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Simple Krama

Ways of Wearing the Krama

A Limited History of the Krama

Cambodian Cotton Cultivation

The Cotton Krama

Don Na Prim

The Silk Krama

Bibliography

The Simple Krama

The ubiquitous unisex chequered krama scarf is an essential component of Khmer Cambodian costume. It distinguishes the Khmer from their neighbours: the Thai, the Vietnamese and the Lao.

The traditional krama was a length of cotton decorated with a red, indigo or black chequered pattern on a white background. The cloth was generally from 40cm to 60cm wide. Today many are woven from cotton mixed with artificial fibres like nylon or polyester.

A Khmer woman dressed in a krama headdress, depicted on a Cambodian 500 riel banknote

Krama are primarily used as a headdress for protection against the sun, but can also be used for multiple, alternate reasons: as a kerchief, a scarf, a shoulder sash, a belt, a hip wrapper, a carrying cloth or even a baby carrier. They make excellent shopping bags and are often used by women carrying produce to market. In the past they were also used as a cover when washing in a lake or river so that clothes could be removed with modesty. The wealthy often distinguished themselves from the rural peasants by wearing a silk krama neck scarf.

A woman wearing a cotton krama headdress at a rural market

Krama have other unusual uses. In the throwing game chol choung, one or more krama are rolled into a ball ensuring that one loose end is left free so that it can be gripped by hand. One team tosses the ball over the heads of the other team, who attempt to catch it and throw it back so that it hits a member of their opposing team.

In the ancient Khmer martial art called bokator opponents armed with bamboo staffs fight each other using their heads, shoulders, elbows, fingers, knees and feet. The combatants wrap kramas around their waist, head and sometimes fists. The skill level of each martial artist is indicated by the colour of their kramas, white being the lowest and black the most advanced.

According to Gillian Green the precise Khmer nomenclature for these cloths is not krama but pha kromah, literally ‘cloth-kromah’, the term kromah presumably derived from the Middle Persian word kamar, meaning a belt or girdle – as in kamar-band (Green 1997, 90). Another term used in Cambodia is kansaen, defined as a light shawl formerly worn by women, or a scarf, headcloth or towel (Jenner 1982, 378).

Return to Top

Ways of Wearing the Krama

Chea Narin et al have described how the versatile krama was not only used as a head cover but was adapted in various different ways as an alternative item of clothing (2003, 98-103):

As a Sampot

Larger krama that were at least one and a half meters in length and 70cm wide could be worn as a sampot – a man’s or woman’s hip wrapper. The cloth was wrapped tightly around the waist from the back, with one end overlapping the other at the front. The overlapping cloth was then tucked inside the inner layer of cloth at the waist to hold it in place. Alternatively the overlapping ends around the waist could be rolled down with the palms of the hands to form a waist belt.

This offered a light form of clothing that could be worm around the home, working in the fields or for bathing in the local river.

A cyclist in Prey Veng Province wearing a light cotton krama as a hip wrapper

As an Eam

A large krama can also be wrapped around the upper torso as an eam, from the back to the front under the armpits, covering the body from the chest to the upper thighs. Both ends are brought to the front and are then crossed, brought over the shoulders and are tied behind the neck. Adults can wear the krama as an eam in combination with a sampot or with shorts or trousers. Women wear an eam over a shirt when doing physical work.

As a Shirt

Boys and men sometimes wore a krama in place of a shirt. There were two alternative ways of folding a krama to make such a garment.

To make a shirt for a boy, the krama was folded in half and the corners were tied together to form a bag. One open side of the bag was then tied in thirds to form three openings – the central one for the head and the outer two for the arms.

To make a shirt for a small girl, each end of the krama was tied together to form sleeves. One third of the krama was folded over and the ends on the shorter upper piece were tied to the sides of the larger lower piece to form sleeves.

As a Chang Pong

To make a chang pong breast cover for a woman, the krama was wrapped around the chest from the back and overlapped at the front. The top was then rolled down and knotted to tightly cover the bosom leaving the lower stomach uncovered.

Return to Top

A Limited History of the Krama

The origins of the chequered krama remain unclear. Some have suggested that it may have migrated to Cambodia from South India via Malaysia and Thailand. Another theory is that the krama may have been introduced as a form of turban from the ancient state of Amaravati in southern India following a royal marriage.

According to the Director of the National Museum of Cambodia, Hab Touch, the krama dates back to at least the pre-Angkor Norkor Phnom era, dating from the first to the fifth century CE. Many statues of Siva and the other Hindu gods dating from that period have been recovered from the Angkor Borey site wearing the kben, a large krama worn as a simple hip wrapper rolled at the waist. One statue even depicted a man wearing a head wrapper in the style of a krama.

When the Chinese envoy Zhou Daguan spent eleven months at Angkor Thom in 1296-1297 he left us a detailed account of everyday life at that time (1902). He made no mention of headwear but recorded that people of all ranks, from the prince down to the common people, went bare foot, wore their hair in a bun, had bare shoulders and simply wrapped their loins with a piece of cloth. Women went bare breasted. When people went out they draped a larger cloth over the smaller one. There were many qualities of fabrics, some produced locally, others imported from Champa and Siam but the most esteemed from the western seas.

The Cambodians did not raise silkworms at that time and their wives did not know how to sew. They only knew how to weave cotton cloth from kapok. However they could not use the spinning wheel and spun their hanks by hand. They also had no weaving looms. They simply tied one end of the web to their belt while working on the other end using a bamboo shuttle.

The implication is that their simple sampot hip wrappers would have been woven from cotton and would be roughly the same size as a large krama.

In far more recent times, krama appear in some of the earliest images of Cambodian costume taken at the end of the nineteenth century. The young French photographer and explorer André Salles was one of the first to archive scenes of daily Cambodian life in photographic form in 1896.

Above: a woman with a krama head cloth at Kampong Chnang market in 1896

Below: a rural farmer wearing a krama neck cloth in 1896

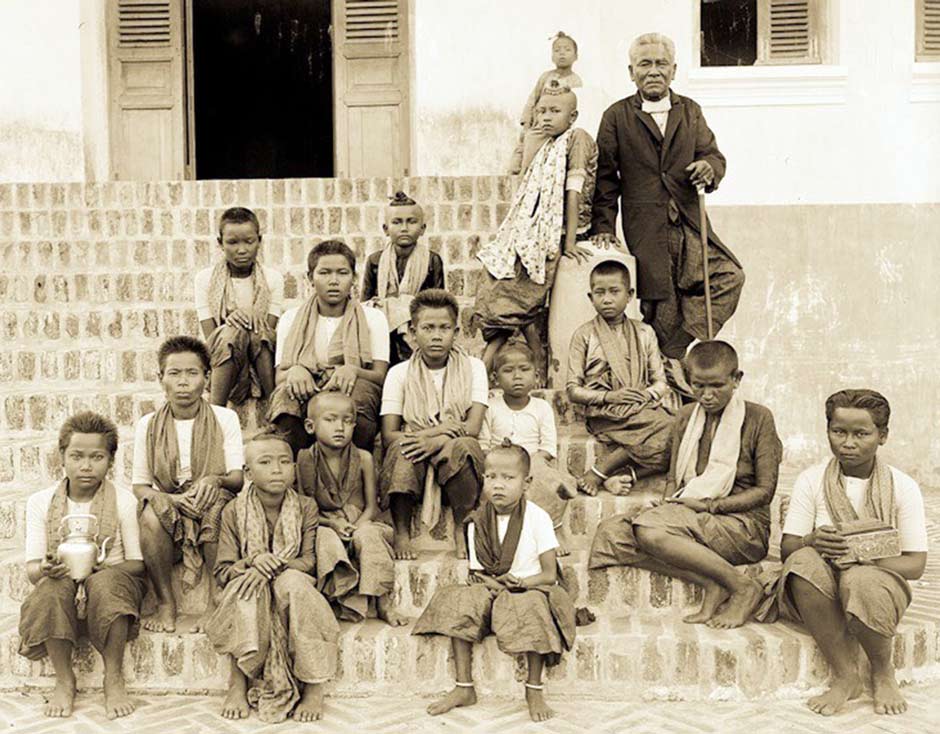

It is interesting that in another photograph taken by André Salles, a regional governor stands with his daughters and servants outside his residence at Pursat, located half way between Phnom Penh and Battambang. All but the governor are wearing neck scarves, only two of which look like chequered krama. The other nine scarves appear to be more sophisticated and in some cases might be silk. The image supports the view that more prosperous Cambodians distinguished themselves from the common people by using more expensive textiles.

Governor Suos with his daughters and attendants at his Pursat residence in 1896

Good early twentieth century photographs of ordinary people are sparse but the following image of daily life at the covered market in Siem Reap shows many traders and customers with chequered krama. The market had only just been erected two years previously and was located close to the riverside landing place near the town centre.

The new covered market at Siem Reap around 1927

Biblioteque National de France

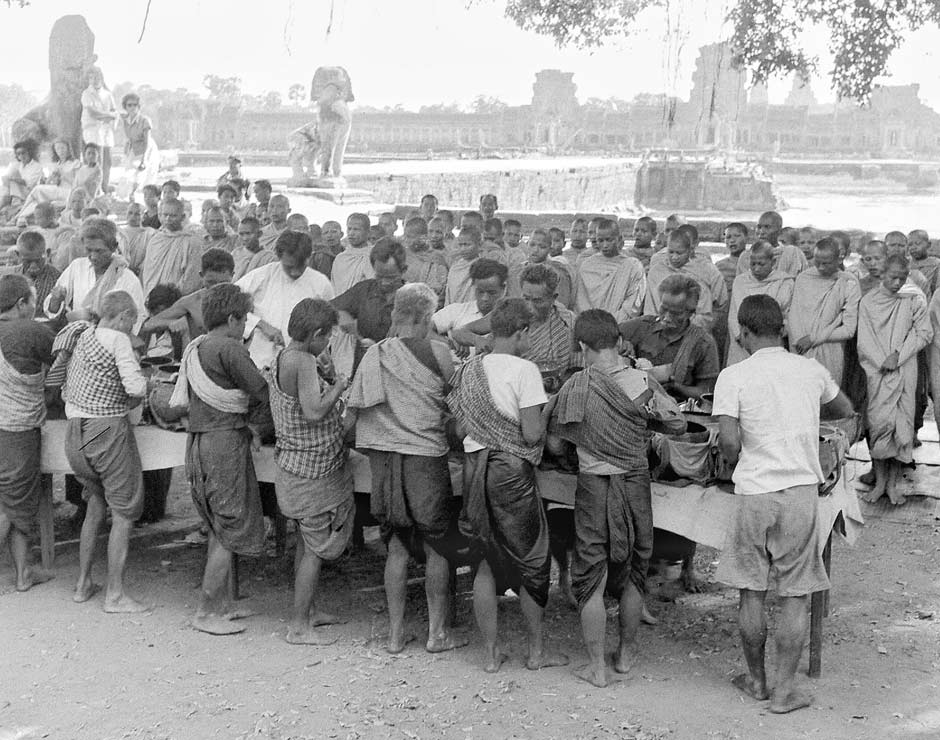

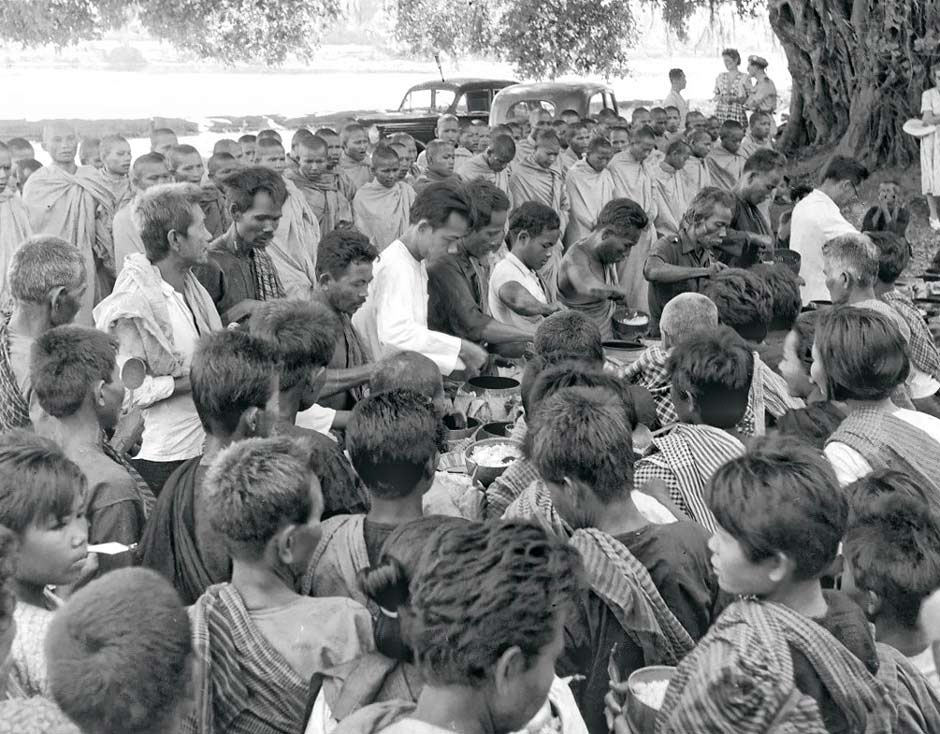

Two later images of a religious ceremony being performed at Angkor Wat in 1949 illustrate the widespread the use of krama by ordinary men at that time.

Above and below: Men preparing monk’s food bowls at Angkor Wat in 1949

In 1946 the Protectorat Français du Cambodge had been granted self-rule and allowed to hold elections. Three years later its protectorate status was abolished and Cambodians were given control of most administrative functions. Full independence from France was finally granted in 1953 and Cambodge became the Kingdom of Cambodia ruled by King Sihanouk. It only survived for two decades before falling under the control of the Marxist mass-murderer, Pol Pot.

Despite coming from a middle class family and receiving his further education in Paris, the young Pol Pot quickly turned into a fanatical Stalinist. After returning to Cambodia in 1953 he quickly advanced in the labour movement and by 1963 had gained the leadership of the Communist Party of Kampuchea. In 1968 he and his supporters launched an insurrection against King Sihanouk’s government, although parliamentarians led by Marshal Lon Nol, not communists, deposed Sihanouk two years later leaving him to seek exile in Beijing and Pyongyang. Encourage by the Chinese, King Sihanouk soon sided with the Khmer Rouge. In April 1973 he even travelled from Beijing to the Khmer Rouge liberated zone of Cambodia to pose for propaganda photographs dressed in Khmer Rouge uniform, red krama included.

King Sihanouk (second from right) and Queen Monineath posing with kramas with the top Khmer Rouge leader Khieu Samphan (third from left), next to a milestone marking the distance to Phnom Penh. 10 April 1973.

After a bitter struggle against Lon Nol, the Khmer Rouge victoriously entered Phnom Penh in 1974 and Lon Nol fled to the USA. The Khmer Rouge quickly abandoned the united front with King Sihanouk who was effectively left as a prisoner in his own royal palace.

During their cruel and chaotic reign, Khmer Rouge loyalists and cadres adopted the simple cotton krama as a symbol of their Khmer heritage. The red and white checked krama was worn with austere black shirts and trouser, Ho Chih Minh sandals made from tyre rubber and sometimes a Mao cap. The State Warehouse Department in Phnom Penh even stocked cotton krama cloths that it delivered to Communist Party of Kampuchea organisations throughout Cambodia.

The Khmer Rouge mass-murderer Pol Pot with a cotton krama

Under Pol Pot’s reign of terror, villages were collectivised and urban dwellers were forced out of the towns into the countryside to work as agricultural labourers. Women were raped and forcibly married.

The Khmer Rouge was paranoid that Vietnamese spies had infiltrated its ranks. Special suspicion fell on cadres located in the Eastern Zone contiguous with Vietnam. These unfortunates were considered to be impure Khmers with Khmer bodies but Vietnamese minds. In late 1977 they were forcibly evacuated to the northwest province of Pursat and issued with special blue krama that marked them out as traitors. The wearing of one of the special blue krama marked the possessor for eventual execution. The blue kramas concerned were cheap, low-quality factory-produced cloths made in Phnom Penh.

Leaders of the Khmer Rouge with kramas meeting a foreign delegation in Phnom Penh in 1975. Pol Pot is on the far left. Photographed by Heng Sinith.

While the weaving of the working class cotton krama was encouraged, the silk weaving industry was seen as bourgeois and was outlawed, the mulberry trees being deliberately destroyed. The making of cotton krama was the only weaving activity permitted (Green 2003; Muan and Daravuth 2003).

Three female Khmer Rouge cadres working in a textile workshop, presumably weaving krama

Documentation Centre of Cambodia Archives

Under Pol Pot’s monstrous period of rule, an estimated 1.5 to 2 million Cambodians died of starvation, execution, disease or overwork. The Khmer Rouge regime was finally brought to an end in early 1979 following the invasion of the Vietnamese army. Terrified survivors of the genocide, many either starving or sick, fled to the border and into Thailand, creating a massive humanitarian crisis.

A refugee mother in 1979 wearing a krama headdress

Long lines of Cambodians dressed in krama wait in for food inside a refugee camp on the Thailand/Cambodia border in 1979. Photographed by Jay Mather.

The Khmer Rouge had left the country bankrupt and in ruins. The once beautiful capital of Phnom Penh had become an urban wasteland of blackened and bombed buildings unfit for habitation.

Cambodia has never fully recovered from the cultural devastation brought about by Pol Pot’s decade of Stalinist insanity. Most farmers had stopped raising silkworms in 1970, so even in the mid-1990s there were hardly any farmers still engaged in sericulture (Morimoto 2002). The skills involved in producing silk yarns and in binding and naturally dyeing them to make traditional silk ikat had been almost lost, save for a few elderly women who still remembered the processes involved. When Morimoto Kikuo conducted a survey of weaving in Cambodia for UNESCO in 1995 he discovered that once important sampot hol producing area of Koh Sutin in Kampong Cham was only produced cotton krama (Green 2003, 47).

Nevertheless the krama retained its popularity in the post-Khmer Rouge era. Even Prime Minister Hun Sen sported a krama when he was electioneering, displaying his humble origins as the son of a farmer (Ly 2019, 84). However although the tradition of weaving and wearing the krama survived the Pol Pot era, the cultivation of cotton did not, as we shall see in the following section.

Return to Top

Cambodian Cotton Cultivation

According to the late Cambodian linguist, Judith Jacob, the modern Anglicised Khmer terms for cotton are either krapās or kappās, after the Sanskrit karpasa (1993, 291). Stoeckel used the word krebas while others have sometimes used krebah. Raw cotton in the form of picked cotton bolls is called samley.

It is clear that cotton has been utilised in Cambodia for millennia - the word krapās has even been identified in a Khmer 700 CE pre-Angkor inscription (Jacob 1993, 311). The word krapās has also been found inscribed on the ninth century Sar Sar 100-Column Pagoda in Sam Bor District and on the tenth century Tvea Kdei Temple.

In more recent times there are several historical reports indicating that in the mid-nineteenth century cotton was being grown along the banks of the Mekong. This was a troubled time, with the country racked by famine, fighting, refugees and epidemics and the local Chinese-controlled economy in ruins after decades of Vietnamese subjugation and recent attacks by the Siamese. When the French missionary M. C-E. Bouillevaux travelled north along the Mekong to the region of Stieng in 1851, he observed that before reaching Peam Chileang, about 90km north of Phnom Penh:The banks of the river are houses of Chinese people devoted to the cotton. This plant grows very well in the sandy land that borders the Mekong.

In 1859 the French naturalist Henri Mouhot noted that cotton was an important article of commerce in Cambodia and thrived there admirably. In Phnom Penh he found that a crowd of small merchants had flocked to the great bazaar to buy cotton, which had been gathered in before the rains (Slocomb 2010, 35).

In 1876 the archaeologist Étienne Aymonier reported that the major products of Tboung Khmum Province, on the east bank of the Mekong River opposite west bank Kampong Siem in Kampong Cham Province, were cotton, tobacco and mulberry trees, all of which were cultivated on the riverbanks.

The production of cotton in Cambodia at the beginning of the twentieth century was briefly described in 1923 by Jean Stoeckel, the Assistant Director of the Cambodian School of Arts (Stoeckel 1923, 395). The Old World cotton species Gossypium herbaceum grew easily on all of the riverbanks that were exposed to, and fertilised by, the annual flooding, especially on the banks of the Mekong River from Phnom Penh as far north as Kratie. Stoeckel specifically mentions the districts of Khsach Kandal, Kos Sutin, Kampong Cham and Krouch Chhmar.

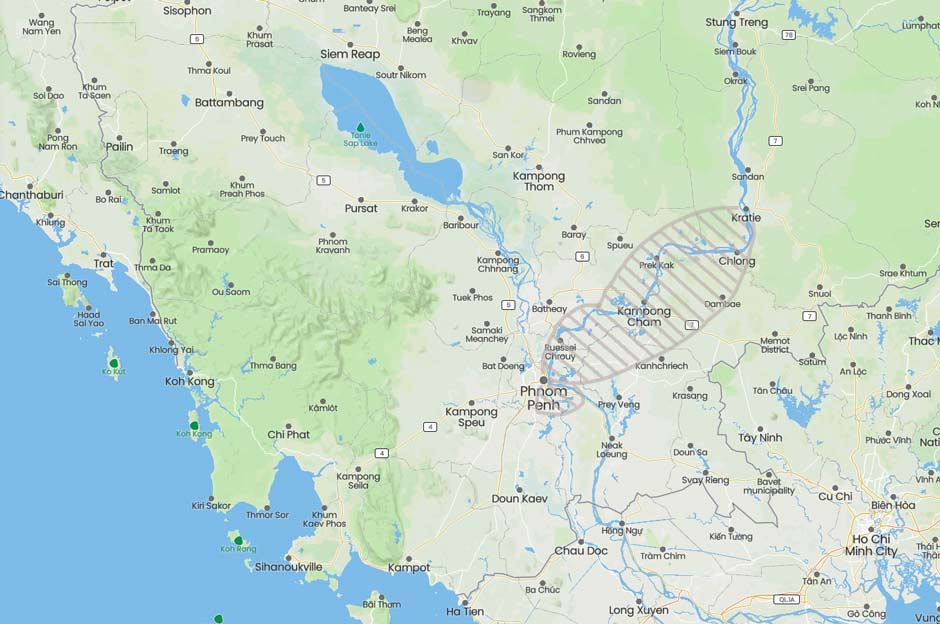

The main Mekong cotton-growing region in 1923, after Stoeckel

Cottonseeds were planted towards the end of the rainy season and he cotton bolls were harvested in March and April. Surprisingly the Cambodians never spun their own cotton. The entire cotton crop was sold to European and Chinese spinning firms and later repurchased as spun yarn. The only spinning mill that existed within Cambodia at that time was a French operation based in Phnom Penh manned by Vietnamese and Chinese workers.

It seems that over the following two decades cotton growing continued to thrive in Cambodia. Surprisingly during World War II a large cotton gin and spinning factory was set up in Phnom Penh by Société Cottonière de Nam Dinh and a second mill established to use the spun yarn for the production of cloth and clothing (Steinberg 1959, 215).

However after the war, cotton cultivation declined significantly as farmers switched to more profitable soybean cultivation or to tree crops like rubber and banana.

Following independence in 1953, the first five-year plan placed a high priority on a revival in cotton farming. Commercial cotton cultivation increased from a miniscule 1,000 acres in 1956 to 15,000 acres in 1966, with the crop completely destined for domestic consumption (Munson 1968, 222). The main crops were located along the Mekong and Bassac Rivers and in the provinces of Kampong Cham and Battambang (Munson 1968, 230). To extend the labour force refugees were forced to work in the Kampong Cham and Battambang cotton fields. Several French-owned cotton mills were also set up during this period.

It seems that the small cotton industry thrived until the early 1970s when the outbreak of fighting resulted in another complete collapse in cotton cultivation. It was estimated that the 1971/72 harvest dropped by 90% from the level of 1969/70 (Whitaker 1973, 270). Under the Khmer Rouge virtually the entire agricultural sector was re-focused on the production of rice and cotton cultivation remained minimal.

Although a limited amount of cotton continued to be grown after the expulsion of the Khmer Rouge, lack of demand coupled with an insect infestation resulted in farmers almost completely abandoning the crop by 1985, switching instead to in-demand crops like cassava, beans and cashew nuts. Not long afterwards the remaining cotton mill in Kampong Cham was closed.

Since 1979 Cambodia has developed a huge garment production sector, now Cambodia’s largest industry employing about 750,000 workers. Yet shockingly, despite having ideal conditions for growing cotton, all of the country’s cotton fibre and cloth is imported from elsewhere (Naron 2012, 237).

Trucking Cambodian garment workers back to their village in Kampong Chhnang Province

Today the around 90% of imported machine-spun cotton yarn arrives from Vietnam, which operates some 102 spinning factories, with the rest sourced from China. The tragedy is that local cotton could be produced at just 20% of the cost of imported cotton.

Return to Top

The Cotton Krama

The basic cotton krama was once the universal multipurpose cloth for the ordinary people of Cambodia. Today krama are less likely to be seen as Cambodians have increasingly adopted western dress. Today most men and women wear western-style clothes such as shirts, blouses, shorts, jeans and skirts, sometimes along with bush hats, pork-pie hats or baseball caps. However krama are still frequently encountered as headwear or body wrappers, especially in rural areas.

A woman weaver wearing a cotton krama in a remote region of Rattanakiri Province

A pair of well-worn krama drying on a fence at Sai Va, Prey Pdao Commune, Prey Kabas District, Takeo Province

The extent of their continued popularity can be gauged by the large quantities of krama that can be seen on sale in most major markets. However today most of these are mass produced and woven from artificial fibres such as polyester or a 50:50 mixture of nylon and cotton.

Piles of krama on sale in a Cambodian covered market

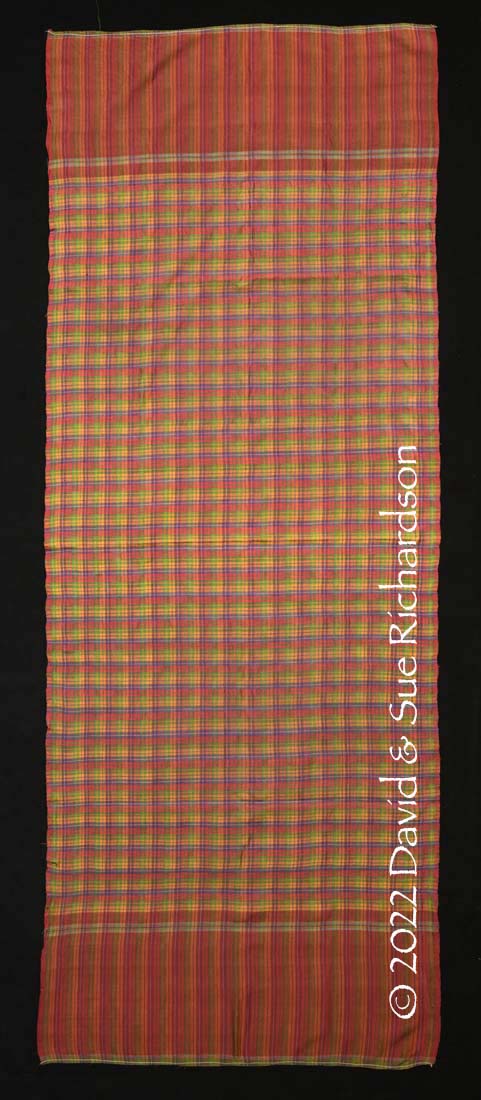

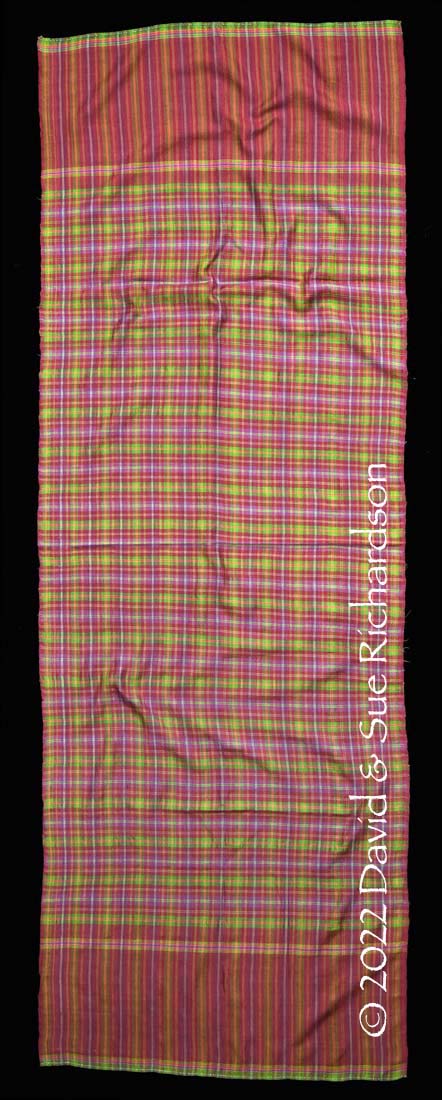

Higher quality cotton kramas tend to be made in specialist kampongs rather than big commercial workshops. The following three cotton krama were all produced in 2010 at kampong Don Na Prim in Prey Veng Province, a weaving centre that is reviewed in the following section below.

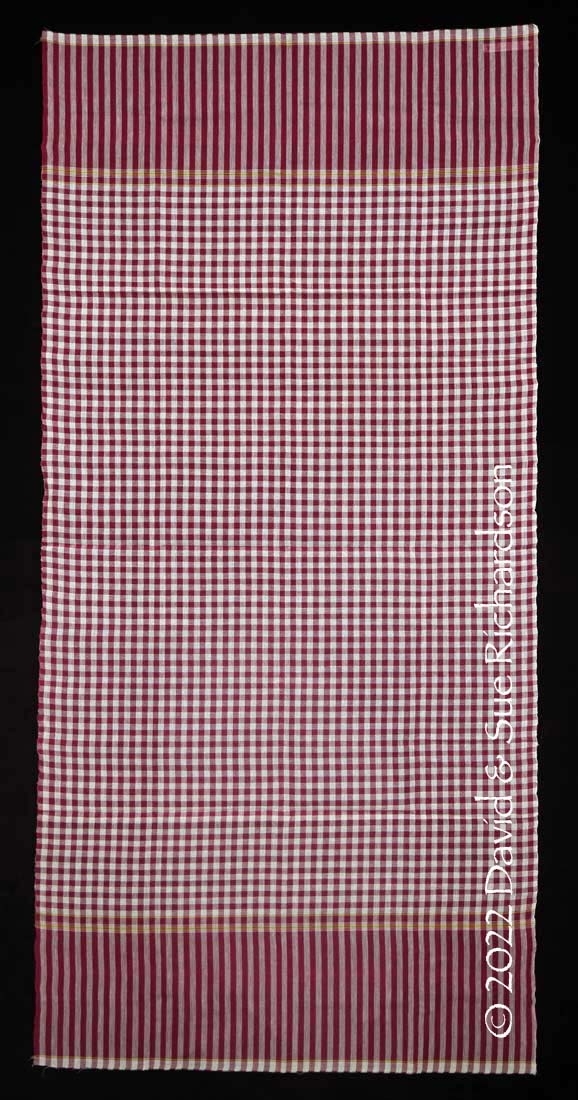

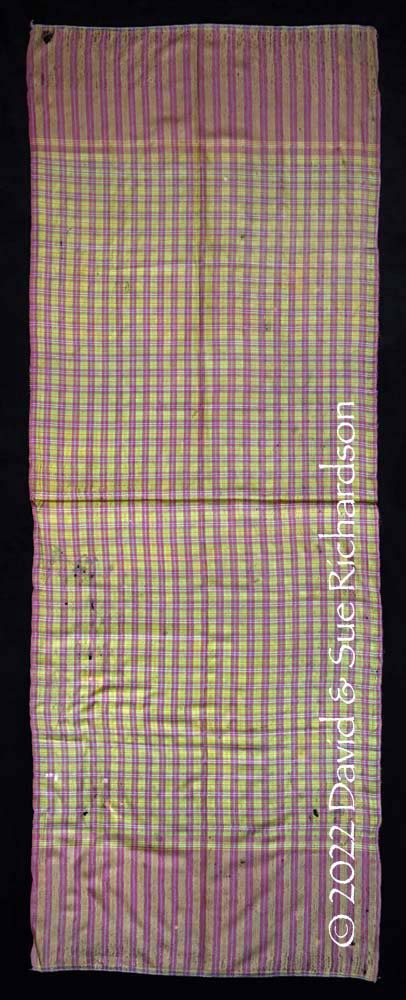

Cotton krama from Don Na Prim, 79cm by 162cm. Richardson Collection.

Cotton krama from Don Na Prim, 79cm by 164cm. Richardson Collection.

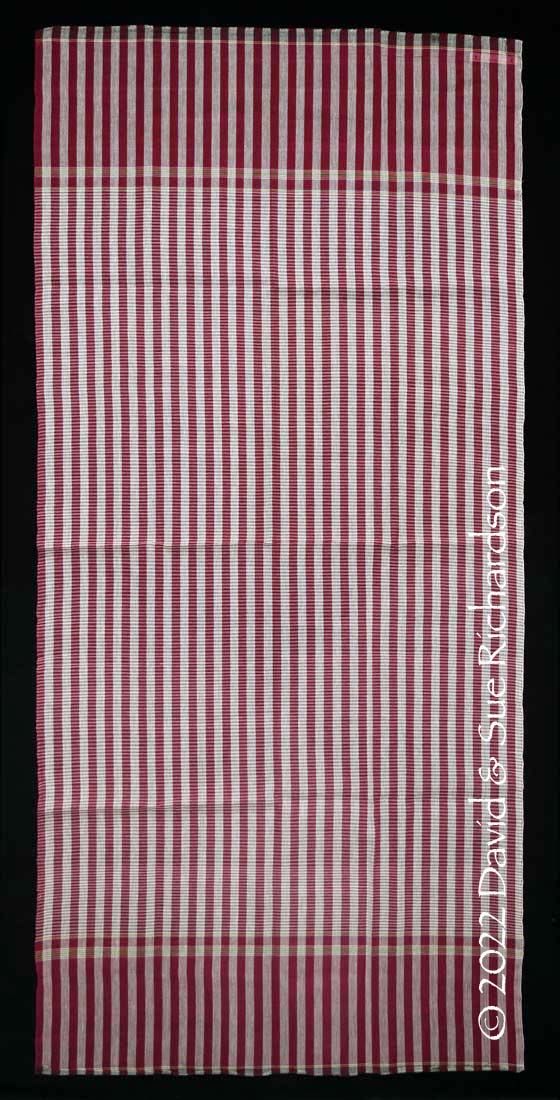

Cotton krama from Don Na Prim, 80cm by 170cm. Richardson Collection.

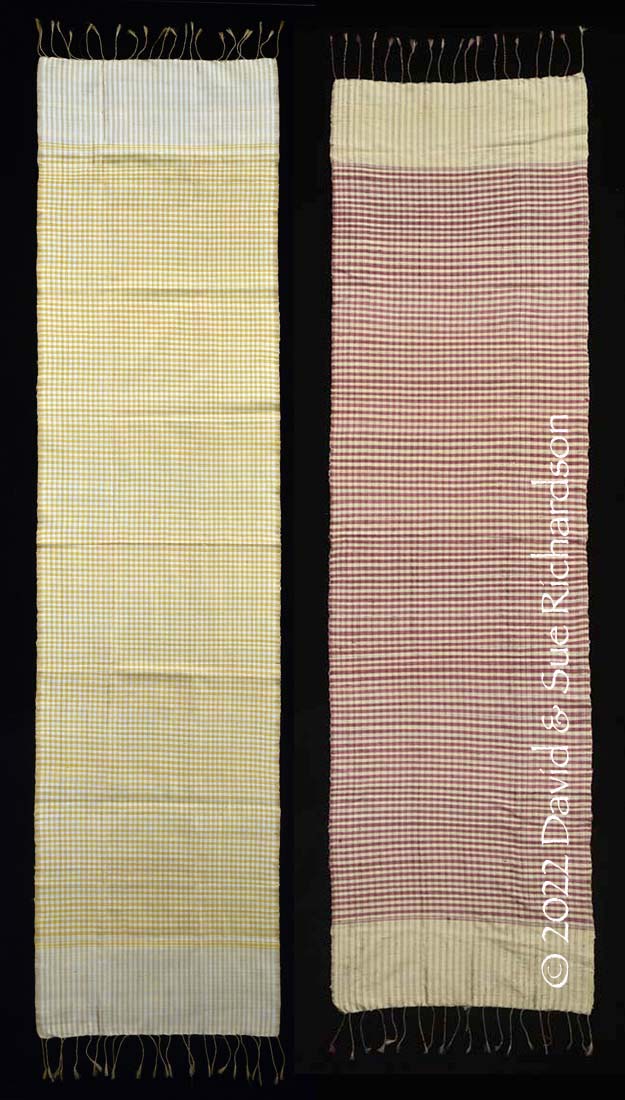

Today more contemporary high quality cotton krama are being made in Takeo Province, more as a fashion accessories rather than a traditional cloth for the common man or woman.

The following two krama have been woven with alternating coloured warps and alternating coloured wefts. For example, the first has alternating mushroom grey and white warps and alternating green and white wefts. The chequered effect in the centre field is achieved by repeatedly reversing both the warp sequence and the weft sequence after a defined number of yarns.

A pair of textured cotton krama woven in Takeo Province, left 35cm by 146cm, right 35cm by 145cm. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Don Na Prim

In the past many Khmer women wove krama in their home, just for themselves and their families, some using locally grown cotton. Today they are mainly produced in urban workshops or in small rural cottage industries scattered across Cambodia, with several families within the same kampong cooperating in a single endeavour.

A fine example of one important rural production centre is at the kampong of Don Na Prim in Prek Chang Kran Commune, Sithor Kandal District, Prey Veng Province. This was at one time a centre of top quality silk weaving. In 1938 the French archaeologist and art scholar Eveline Poree-Maspero observed that silk sampot from Prek Chang Kran were reputed for their superior qualities by the Cambodian Royal family and other local elites (Green 2003, 192). Following the outlawing of silk production, the weavers in this kampong survived the Pol Pot genocide by refocussing their weaving on cotton krama.

Prek Chang Kran (sometimes Prek Changkran) is located on the banks of the small Tonle Touch River, which flows parallel to and south of the much larger Mekong River. It is located 17km northwest of Prey Veng town and about 18km southwest of Kampong Cham. In 2003 it had 1,313 houses and a population of around 6,900. Despite being occupied by talented dyers and weavers, the commune suffered from widespread poverty with average incomes calculated at that time as $0.54 per person per day ($200 per annum).

Today the people of Don Na Prim have refined their krama production process to maximise productivity. Hanks of machine-spun Vietnamese cotton are grouped together to make super-hanks that are then coloured by hand with synthetic dyes in large metal troughs. After massaging the dye into the yarns, the hanks are attached to large metal hooks and tightly wrung dry by pulling hard on the arms of a rotary winch.

Above: dyeing yarns either red or yellow in metal vats

Below: drying out the dyed yarns using a mechanical wringer

Before weaving, the yarns - both dyed and undyed - are first starched by soaking them in rice water made by dissolving milled rice flour in water. They are then hung out to dry.

Hanks of starched yarn hung up to dry at Dom Na Prim

The yarns are woven on a Cambodian wooden frame loom, known as a kei thbanh, which has a rectangular box structure supporting two or more heddle shafts (thnhkar bae) for raising and lowering string heddles (tangkar phka) (Green 1997, 86). The traditional loom is around 4 to 5 metres in length but modern looms are much shorter. Krama are woven on a two-shaft frame loom operating a double heddle. However some workshops elsewhere operate with more productive flying shuttle looms (kei con tra).

Krama are woven in multiple quantities in a continuous length, not individually. This requires a tricky warping up process to produce a warp set of alternating coloured warps that can be up to 100 metres long.

Above and below: weaving a continuous length of red and white chequered cloth on a two-heddle loom. This will later be cut into simple individual krama

Weaving a long continuous length of individual krama with a bold check and end sections

Two examples of finished krama at Don Na Prim

The finished krama are not marketed directly but are sold in batches of ten to local Prek Chang Kran wholesalers.

A local wholesaler with bolts of krama packaged in tens

There is another nearby important cotton krama weaving centre just north of Prek Chang Kran on the islands of Koh Sutin in the Bassac River just south of Kampong Cham. This community specialise in red and white or blue and white chequered cotton krama, many destined for the markets of Phnom Penh. Recently the workshop at Moha Leap Commune has been upgraded with high-speed mechanical looms powered by electric motors. Further south some cotton krama are also woven on Koh Dach Island, although most of the weaving at that location is based on silk. It is located in the Mekong River just a few miles north of Phnom Penh. Their krama are also sold to wholesale merchants from Phnom Penh.

Although the Japanese-led NGO Caring for Young Khmer (CYK) specialises in weaving silk ikat (hol and pidan), some of the weavers working at its weaving centre in Trapaing Krasaing Commune, Bati District, Takeo Province, produce naturally dyed cotton kramas. These are sold through its outlet in Phnom Penh.

Another NGO called Krama YuYu, founded by the Japanese woman Tomoko Takagi, operates a workshop at Ta Pouk in Bakong Commune some 20km from Siem Reap. Here some 35 weavers specialised in producing contemporary coloured, naturally dyed cotton kramas as fashion accessories for export. However in recent years they have diversified into weaving silk hol using both Vietnamese and Cambodian silk.

Return to Top

The Silk Krama

In Cambodia a silk krama is known a krama saut, saut being the Khmer word for silk.

As already mentioned, in the past some wealthier Khmers distinguish themselves from the peasants by wearing krama woven from silk, a less practical fabric in such a tropical climate, especially given that cotton is by comparison cooler, lighter, and more easily washable. It has even been reported that during the Pol Pot era some high-ranking cadres wore silk kramas despite the ban on bourgeois silk textiles (Gardere 2010, 407).

Traditional silk krama appear to have been larger than their cotton equivalent – around 55 to 60cm wide and 150 to 170cm long.

Many women kept a silk krama as a family heirloom, which they brought out for important events such as weddings. Today the main ceremonial attire for women consists of a silk pleated sampot hip wrapper, a cotton or lace aor blouse and frequently a krama saut worn asymmetrically on the shoulder (Berthon 2021, 60).

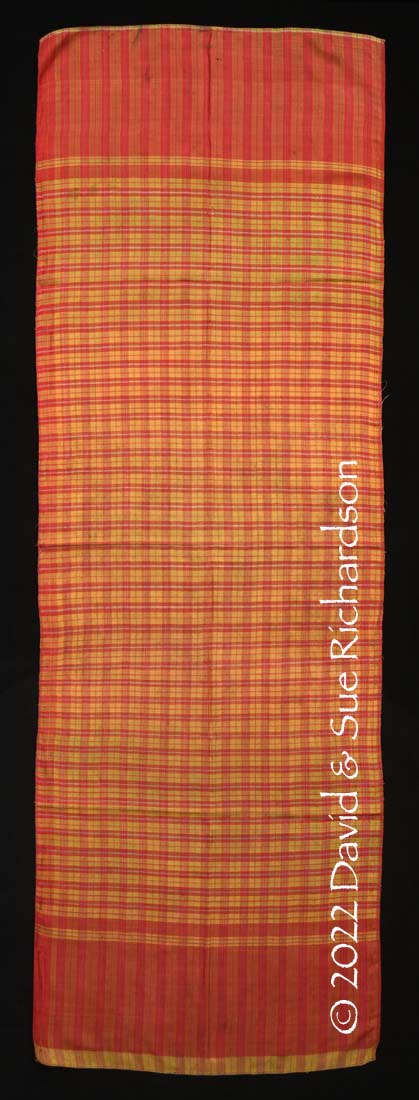

The Richardson Collection contains more than half-a-dozen krama saut that were woven prior to the arrival of the Khmer Rouge in 1970. The oldest two are relatively light and simple having been woven from very fine silk. They were both acquired in Phnom Penh with no provenance:

Two simple fine silk krama, above 54.5cm by 152cm, below 56cm by 162cm.

Richardson Collection.

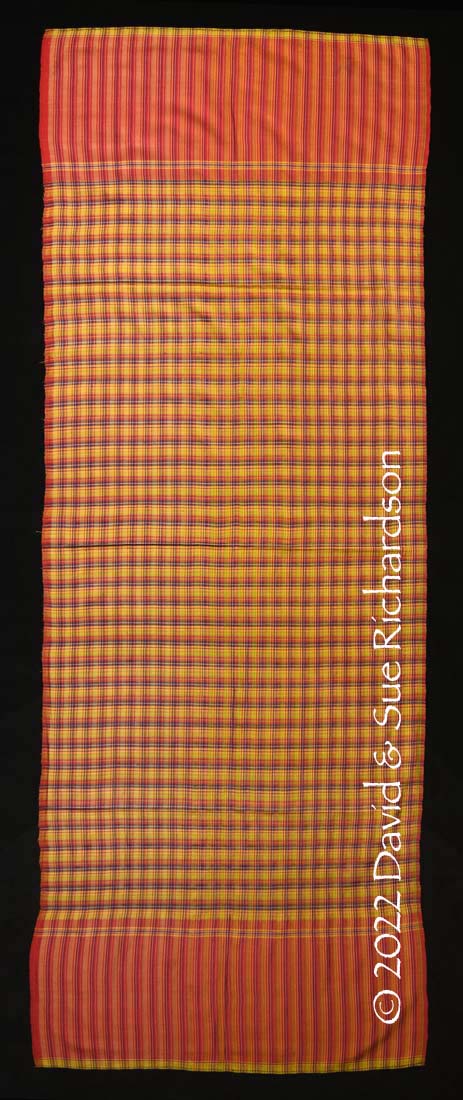

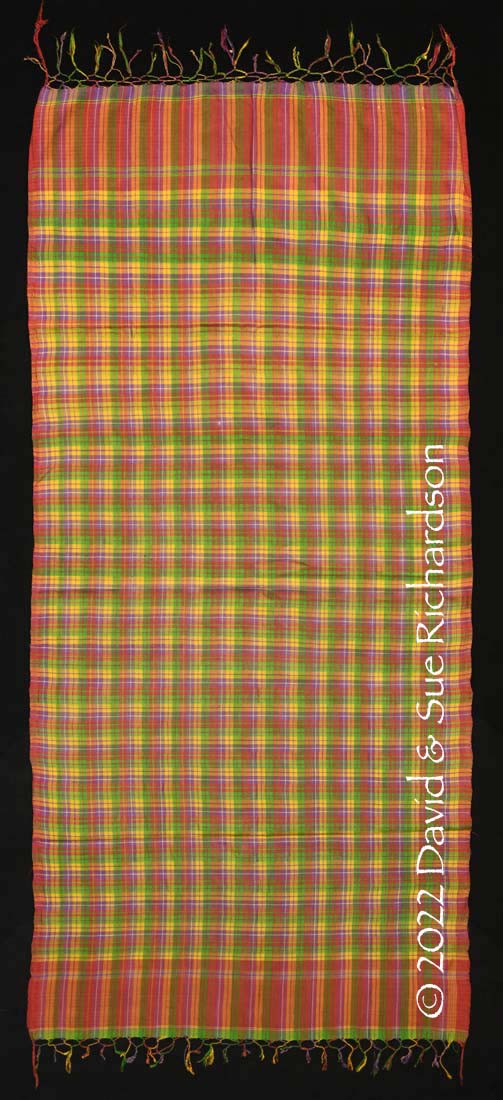

The remaining five were woven at various locations in Takeo Province and are slightly later and more varied in design:

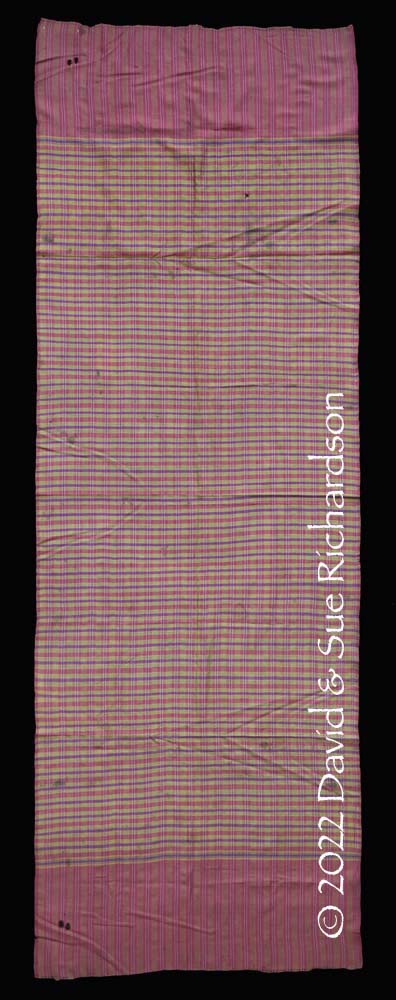

A pre-1970 krama saut, 55cm by 166cm. Richardson Collection.

A pre-1970 krama saut, 62cm by 162cm. Richardson Collection.

A pre-1970 krama saut, 60cm by 134cm. Richardson Collection.

A pre-1970 krama saut, 57.5cm by 152cm. Richardson Collection.

A pre-1970 krama saut, 57cm by 162cm. Richardson Collection.

In recent decades silk krama have been transformed into a fashion accessory sold in boutiques of Phnom Penh and Siem Reap and exported abroad. Most are woven from mulberry silk imported from Vietnam, which has been a major silk producer for at least a thousand years.

Hanks of Vietnamese silk manufactured at Tan Chau on the Mekong, just across the Cambodian border directly south of Phnom Penh

However the number of weavers involved in this activity is relatively small. In 2005, Dongelmans, Seng and Ter Horst could only identify 1,113 silk krama weavers in the whole of Cambodia. Even today, in the important silk weaving centre of Koh Dach, just upstream from Phnom Penh, only 401 of the 5973 weavers (7%) are producing silk krama for the tourist market.

Other silk krama producing centres are at Kein Svay located just east of Phnom Penh on the bank of the Bassac River in Kandal Province and the islands of Koh Sutin in the Bassac River north east of Phnom Penh.

Fortunately in recent decades some artisans have begun weaving silk krama using domestically produced Cambodian golden silk. One of the pioneers in this field was the late Kyoto-born Kikuo Morimoto, who in 1996 established the Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles (IKTT) in a suburb of Phnom Penh, later moving it in 2000 to Siem Reap. The following two silk krama were woven in 2008 by different weavers working at the IKTT workshop:

Two silk krama woven at IKTT, Siem Reap. Left: woven by Phos, 42cm by 173cm. Right: woven by Channy, 43cm by 175cm. Richardson Collection.

Another two were woven in the silk producing village of Paoy Char Commune in Phnom Srok, in the east of Banteay Meanchey Province, bordering Thailand. to the north of the Siem Reap to Sisophon Road:

Two silk krama woven at Paoy Char Commune, left 38cm by 152cm, right 40cm by 146cm. Richardson Collection.

This is another relatively poor community where silk production makes an important contribution to family livelihoods. Most villagers are rice farmers but also raise some livestock. Depending on the extent of their farming activities a 2009 survey found that silk weaving contributed from 15% to 55% of household incomes (Kramer et al 2009).

Return to Top

Bibliography

Berthon, Magali An, 2021. Silk and Post-Conflict Cambodia: Embodied Practices and Global and Local Dynamics of Heritage and Knowledge Transference, PhD thesis, Royal College of Art, London.

Daguan, Zhou (Tcheou Ta-kouan) 1902. Mémoire sur les coutumes du Cambodge, translated by Paul Pelliot, Bulletin de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient, vol. 2, pp. 123-177.

Dupaigne, Bernard, 1980. Répartition des Tissages Traditionnels au Cambodge, Cheminements: Écrits offerts à Georges Condominas, Asie du Sud-Est et Monde Indonésien, vol. 11, pp. 327-337.

Fraser-Lu, Sylvia, 1988. Handwoven Textiles of South-East Asia, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Green, Gillian, 1997. The Cambodian Weaving Tradition: Little Known Weaving and Loom Artefacts, Arts of Asia, vol. 27, issue 5, pp. 78-90.

Green, Gillian, 2003. Traditional Textiles of Cambodia: Cultural Threads and Material Heritage, River Books, Bangkok.

Green, Gillian, 2005. Spirit Ships: Ancient Images on Cambodian Narrative Textiles, Arts of Asia, vol. 35, issue 3, pp. 38-47.

Jacob, Judith, 1993. Cambodian Linguistics, Literature and History, Routledge, London and New York.

Jenner, P., and Pou, S., 1982. Mon-Khmer Studies IX-X: A Lexicon of Khmer Morphology, The University Press of Hawaii.

Kramer, Anna Katharina; Lauritzen, Heidi Kristine Bo; Rashid, Harun Ar; and Hansen, Nina Tofte, 2009. Silk for Development - a study on the potentials of silk production as a sustainable livelihood activity in the Paoy Char Commune of Cambodia, MSc dissertation, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen.

Ly, Boreth, 2019. Traces of Trauma: Cambodian Visual Culture and National Identity in the Aftermath of Genocide, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2002. The Revival of Silk Weaving in Cambodia, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 404.

Munson, Frederick P., et al, 1968. Area Handbook for Cambodia, US Government Printing Office, Washington D. C.

Narin, Chea; Sopheary, Chea; Sonine, Kem and Chanmara, Preap, 2003. Seams of Change, Clothing and the Care of the Self in Late 19th and 20th Century Cambodia, Daravuth, Ly, and Muan, Ingrid (eds), Reyum Publishing, Cambodia.

Naron, Hang Choun, 2012. Cambodian Economy, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Slocomb, Margaret 2010. An Economic History of Cambodia in the Twentieth Century, NUS Press, Singapore.

Stoeckel, Jean, 1923. Étude sur le Tissage au Cambodge, Arts et Archéologie Khmère, vol. 1, issue 4, pp. 387-402.

Whitaker, Donald P., et al, 1973. Area Handbook for Cambodia, US Government Printing Office, Washington D. C.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 21 February 2022.