Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kecamatan Ilé Bura

The Ilé Lewotobi Twin Volcanoes

The Kampongs of Ilé Bura

Ethnography

The 1929 Visit of Ernst and Hanna Vatter

Dyeing and Weaving in Ilé Bura

Vatter’s 1929 Textile Collection

Ilé Bura Textiles Today

Kampong Lewo Tobi Textiles

Kampong Lewouran Textiles

Kampong Riang Baring Textiles

Bibliography

Kecamatan Ilé Bura

The district of Ilé Bura (coloured yellow on the map below) is commonly known as either Lewotobi or Loba Tobi. Its nomenclature ‘tobi’ is the local Lamaholot term for the tamarind tree. It is one of the eight kecamatan (districts) of East Flores Regency that are located on the mainland of Flores Island, all of which are governed from Larantuka. It is also one of the six mainland ikat weaving regions of East Flores with a very distinctive style of its own quite unlike that found in the other five regions.

Map of the kecamatan of eastern Flores, with the six weaving areas highlighted

(Map courtesy of Kabupaten Flores Timur)

Kecamatan Ilé Bura is divided into seven desa or village zones:

- Desa Birawan

- Desa Dulipali

- Desa Lewoawan

- Desa Nobokonga

- Desa Nurri

- Desa Riangbura

- Desa Riang Rita

The total population in 2021 was 7,716.

Lewotobi is relatively isolated, located in the very south of East Flores Regency some 50km from Larantuka – a one and a half to two hours journey by car. On the other hand it is only separated from Solor Island by the narrow 3km-wide Strait of Lewotobi. Consequently, there has been a long-standing link between the people of Lewotobi and those of southwestern Solor Island. Today villagers still visit Solor by boat and we have even visited one family where the husband actually works on Solor.

A 1970 map of East Flores, highlighting Ilé Bura. Courtesy of the UK Ministry of Defence

Return to Top

The Ilé Lewotobi Twin Volcanoes

Ilé Bura is dominated by the Lewotobi ‘husband and wife’ twin volcano, which consists of the stratovolcanoes Ilé Lewotobi Laki-Laki (1584m) and Ilé Lewotobi Perempuan (1703m). Both have crescent-shaped summit craters that are open to the north and are less than 2km apart along a NW-SE line.

Above: The twin volcanoes of Lewotobi as seen from Oka, just south of Larantuka.

Below: The cloud-covered twin volcanoes of Ilé Lewotobi as seen from the northwest of Solor Island

While the taller and broader Ilé Lewotobi Perempuan has erupted only twice in historical time, the conical Ilé Lewotobi Laki-Laki to the northwest has been frequently active during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most recently erupting in late December 2023. As a precaution, well over 5,000 residents were evacuated from the region, mostly from neighbouring kecamatan Wulanggitang to the west of Ilé Bura. Then on 9 January some 544 residents of kampong Nurabelen in Ilé Bura fled to Riang Rita. It erupted again in early November 2024, killing nine people and injuring dozens more. Over 11,000 people were evacuated from the region. On 12 November Lewotobi Laki-Laki spewed ash into the sky at least 17 times. According to the Centre for Volcanology and Geological Disaster Mitigation, the largest column of ash was 5.6 miles tall. Dozens of flights into and out of Bali's Ngurah Ria airport were cancelled. Ilé Lewotobi Laki-Laki previously erupted explosively in May 2003.

Above: Volcanic ash rising 1½ km above Ilé Lewotobi Laki Laki on 2 January 2024

Below: Ash clouds viewed from Nobo on the Trans-Flores Highway on 10 January 2024

The eruption of Ilé Lewotobi Laki Laki on 12 November 2024

Return to Top

The Kampongs of Ilé Bura

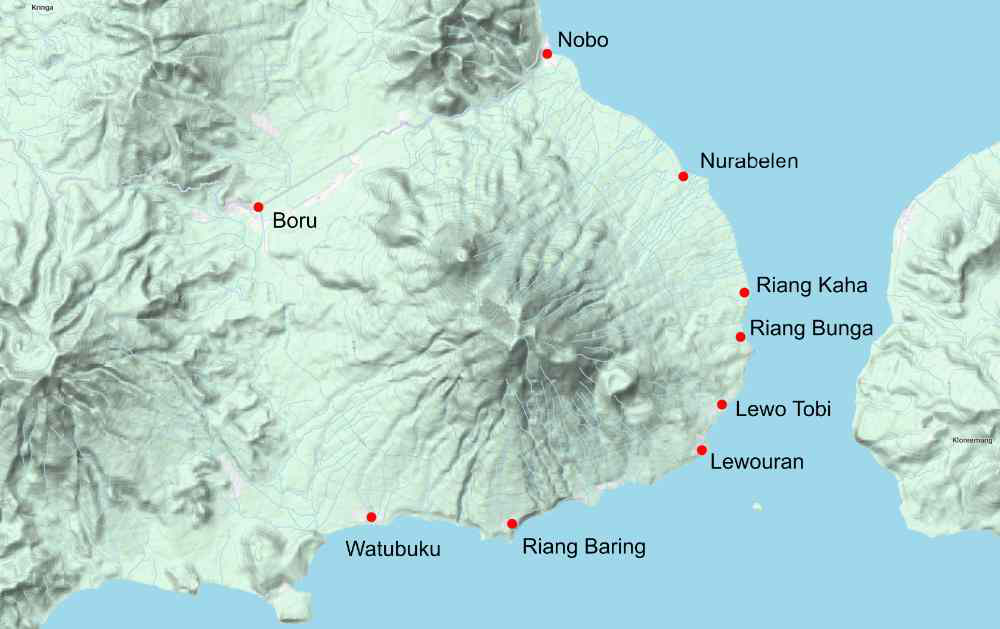

The residents of Ilé Bura all live in villages located on a road that circumnavigates the twin volcanoes. The largest of these villages are found on the coastal road that starts from its northern junction with the Trans-Flores Highway at Nobo. Initially heading southeast, the road passes through the coastal villages of Nurabelen, Riang Kaha, Riang Bunga, Lewo Tobi, Lewouran, Lewobawang, Buranliang, Riang Baring and Watubuku. It then runs north to the west of the volcanos through the smaller hamlets of Tabana, Duang, Bawalatang, Kumaebang and Watupodor before re-joining the Trans-Flores Highway at Boru.

The coastal kampongs of Lewotobi

A side street in kampong Lewo Tobi

A woman fetching water from the well in Lewo Tobi

Roughly 90% of local villagers are dry land farmers who cultivate corn, tubers and cashew nuts, as well as non-irrigated rice, chocolate and copra. When farm work is not possible, particularly during the rainy season from December to March, many farmers turn to fishing.

In the past the whole region was a major centre of weaving, which made an important contribution to family income. Sadly today, weaving is confined to just three villages – Lewo Tobi, Lewouran and Riang Baring, the latter being the most active.

Return to Top

Ethnography

The people of Ilé Bura are linguistically (and ethnically) Lamaholot, spealing their own Lewotobi dialect. Children are born into the clan of their father, known locally as a wun. Individual villages tend to have a mixture of around six to eight clans. For example:

- Lewo Tobi has eight clans: Kedang, Kwure, Kwuta, Muda, Mukin, Temu, Uran and Witi.

- Lewouran has six clans: Kedang, Kwure, Kwuta, Leba, Muda and Uran, while

- Riang Baring with a population of 859 has seven clans: Darang, Hodo, Kwuta, Leba, Mare, Muda and Tobi. An eighth clan, Aran, has recently merged with suku Hodo.

All the clans are exogamous, so young men and women must marry outside of their own clan. Because of this, each individual clan has a long-term marriage alliance with one or two neighbouring clans. As an example, in the kampong of Riang Baring:

| Men from suku: | Can marry women from sukus: |

| Darang | Mare and Tobi |

| Hodo | Darang and Tobi |

| Kwuta | Darang |

| Leba | Darang and Tobi |

| Muda | Leba and Darang |

| Tobi | Kwuta and Mare |

These alliances are asymmetric, so as an example, men from suku Tobi cannot marry women from sukus Darang, Hodo or Leba.

In the past, bridewealth of ivory elephant tusks was donated by the groom’s clan to the bride’s clan. However, as these are very difficult to find today they are substituted with money. The counter prestation is composed of woven textiles, typically five synthetically dyed sarongs.

As in the rest of East Flores, the local people are predominately Catholic.

The Catholic church in Riang Baring

In the early 1950s, Justus van der Kroeff found that in kampong Lewo Tobi the exchange of bridewealth had been heavily influenced by the Catholic missionaries who opposed the payment of bride-price, regarding it as the unholy purchase of the bride by the clan of the groom. As a result, the amount of bridewealth exchange had been reduced. One consequence was the growth of service marriages (geleka) in which some of the bridewealth was substituted by a period of service to the bride’s family. Despite this, the traditional system of bridewealth exchange was still considered to be the ideal.

Return to Top

The 1929 Visit of Ernst and Hanna Vatter

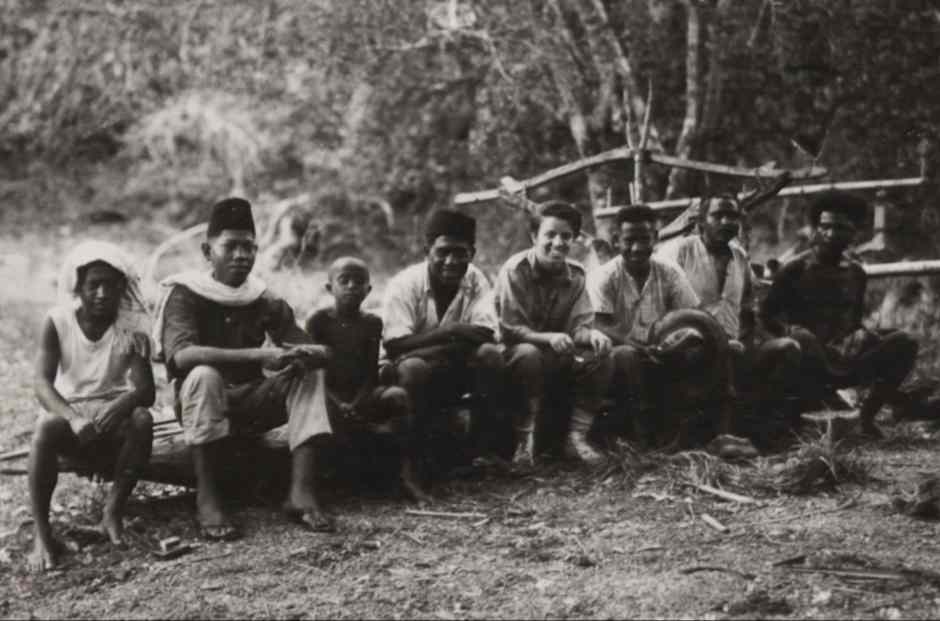

In 1928 Ernst Vatter, a curator at the Ethnographic Museum in Frankfurt, was sent on a professionally planned ethnographic expedition to Eastern Indonesia. Accompanied by his newly wed wife, Hanna, he arrived in Larantuka on 9 November 1928. After initially spending three weeks in kampong Leloba behind Ilé Mandiri they returned to Larantuka in December where during Christmas Hanna Vatter contracted malaria. Consequently in January 1929, Ernst Vatter set out alone with a local priest to explore Bama and Lewotobi (which he described as Lobe Tobi).

The following is a translation of the published record of his visit (Vatter 1932, 142-145):

Our horses had arrived, and so we rode out early in the morning to reach Nobo, the first village on Lobe Tobi, before the rain was due to arrive at midday. Slowly the big "Floresway", which we can follow until Nobo, ascends to the saddle between the Ili Lekluo and Kabalelo. A short time after we reached the top of the pass, we rode down again. The road turned sharply and before us lay a landscape of fairy tale beauty: the bay of Konga, framed by the mountain ranges of Ili Muda and Lobe Tobi, and at the centre of the semi-circular bay in deep blue water lay a small, circular island with a gently rising volcanic cone covered with light green, the island of Konga. Untouched by human hands, like a haunted fairy-tale place, it lies down in the depths, with no village and no field upon it, though only a narrow inlet separates it from the mainland. Slowly we go downhill and our eyes sweep across the bay to the mountain ranges on Solor, which seem to plunge in the south like a huge wall perpendicular to the lovely Tobi Strait. Through the densely forested coastal plain we come to the large village of Löwolaga, where we just take a small snack with the local teacher, and then continue riding, very close to the sea, following the curve of the bay. Dense mangrove forest blocks the view of the sea; Father Strieter tells stories of women and children who have fallen victim to the crocodiles in recent years while bathing or fetching water. We come to Konga, an ancient Christian settlement, in a grove of wonderful coconut palms. Whereas elsewhere a palm tree delivers an average of 100 to 150 nuts per year, the yield here rises to 250-300 pieces. The soil is extremely fertile, but very swampy; the whole area is severely malaria-infested and mortality, especially among children, is incredibly high. Elephantiasis is also very common. As in Larantuka, there is a Portuguese Brotherhood, and some families still have beautiful old saints and Madonnas carved from ivory and wood. Behind Konga, between the sea and the slopes of Ili Muda, we pass through sparse palm forest and wide alang-alang fields to the south; mount Tobi rises before us, great and mighty. Soon after noon, just as the sky begins to cover itself with black rain clouds, we arrive in Nobo. The village is located directly at the foot of the volcano, grey-black as the sky, gloomy and threatening, it hangs over the houses that look like tiny toys. The slopes are ragged and broken, and showered with massive cinder and ash avalanches that reach way down to where people live. When the first raindrops fall, we jump off our horses in front of the stately pastor, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a black goatee, Father Koch, the uncrowned king of the Lobe Tobi region, as he is rightly called, warmly welcomes us into his kingdom, and as powerful as the voice of the Last Judgment, his call booms through the house into the back kitchen: “bawa koppil”, “bring the coffee!”

The next morning Father Strieter returned to Bama while I rode south with Father Koch. The large "Floresway" turns inland in Nobo and bypasses Lobe Tobi to the north. A riding path leads along the coast to the villages at the eastern foot of the volcano. Our destination is Lewotobi ("tobi" is the tamarind tree) located at Lobe Tobi Strait opposite Solor. We cross numerous stream beds filled with rock scree, which luckily still carry little water. The volcanos' loose foothills bear light forests of white-barked kajuh putih (= Whitewood) trees from whose leaves the well-known drug, kajuh putih oil, is distilled. In some places the mountain approaches directly to the sea, then the path leads up and down between mighty boulders, sometimes descending so steeply into a ravine, that even our climbing-trained horses find it hard to make the descent. In places, the narrow beach is littered with black lava blocks. We pass through several villages: Nura Balen, Riang Ka'a, Riang Bunga. Still the picture hardly changes: to the right always mount Tobi with kajuh putih forest, alang-alang steppe and in places corn fields on the slopes, on the left the sea and not far beyond the mountains of Solor. At the height of the steep drop down to the sea, we can clearly see a large village: Läwolöin, the capital of South Solor, which is almost entirely Christian, according to Father Koch, whose office area also includes South Solor.

Today, however, we will not miss the rain: dark clouds were rising, and even before the sun had reached its highest level, it poured down in streams from the sky, so that the waterproof windbreaker no longer held and we arrived in Lewotobi soaked to the skin. The local teacher, a black Portuguese from Larantuka with the full-sounding name Francisco de Rosari and a head like a Moorish knight, met us under a rain hood sewn together from pandanus leaves, and led me to the little rest house, which was embedded near the roar of the surf at the end of the village while Father Koch took up residence in the teacher’s house.

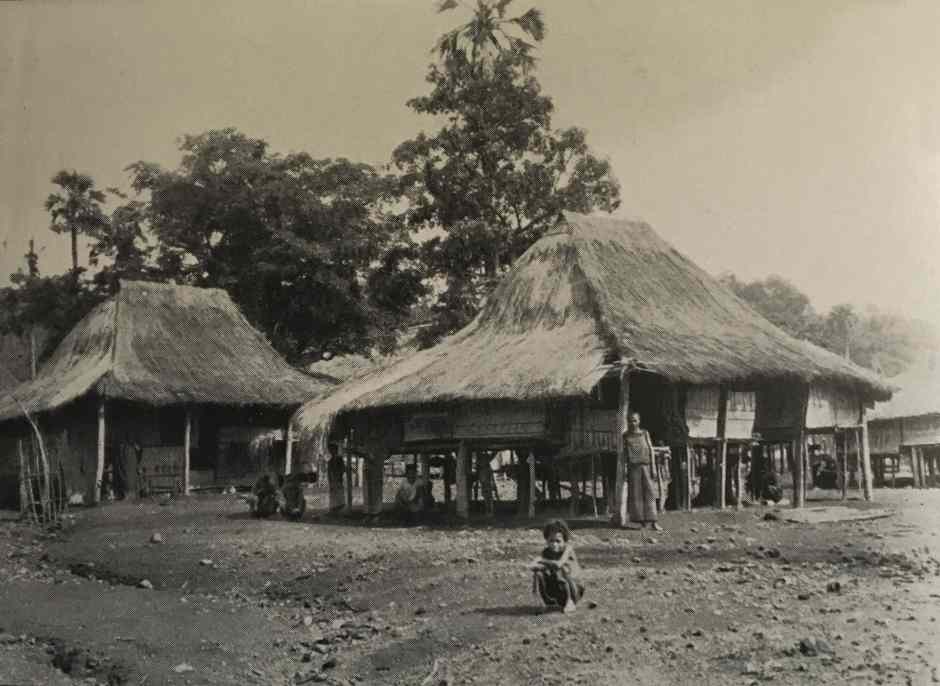

Houses in Lewo Tobi, photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

It is here that the strait between Lobe Tobi and Solor has its narrowest point. Three small black rocky outcrops jut out of the water beyond the exit: Nuan Witi, the Goat Island, Nuan Balen, the Big Island, and Nuan Kowen, the Cloud Island. Nuan Bälen is the Island of the Dead, the land of the ‘kewoko’. According to the prevailing view, the dead souls retain the shape of a human being, only the back is hollowed out. As with Ili Mandiri, they will be tested here before they are admitted to the realm of the departed. First, they go to Nuan Witi; a great sacrificial sword, on whose edge the souls have to cross, which forms the bridge from there to Nuan Bälen, the land of the dead. Only the "good" souls succeed; Anyone who violates the laws of the clan and the village in life, or is guilty of theft or adultery or the violation of food prohibition or marriages, inevitably falls into the sea and is turned into a fish, an ordinary mortal into a small one, a distinguished person into a large one. Even from the Island of the Dead, the "käwoko" stay in touch with the living: They collect the offerings of food and sirih-pinang that are placed on the graves, they are invoked as protection and helpers in the event of illness and other adversity and appear as guests at the great festivals. If you neglect them, for example if you fail to put food on their graves, they take revenge and bring misfortune to the living. However, no effort is put into caring for the gravesites themselves, since the soul of the departed no longer lives in them.

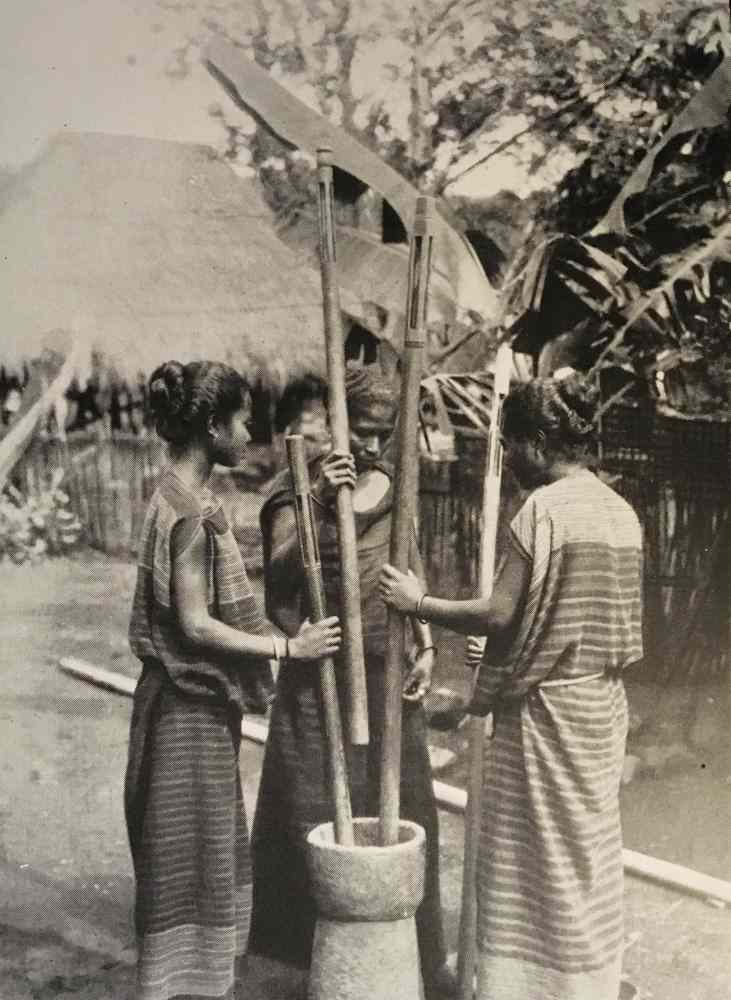

Women from Lewo Tobi rhythmically pounding rice. Vatter 1935.

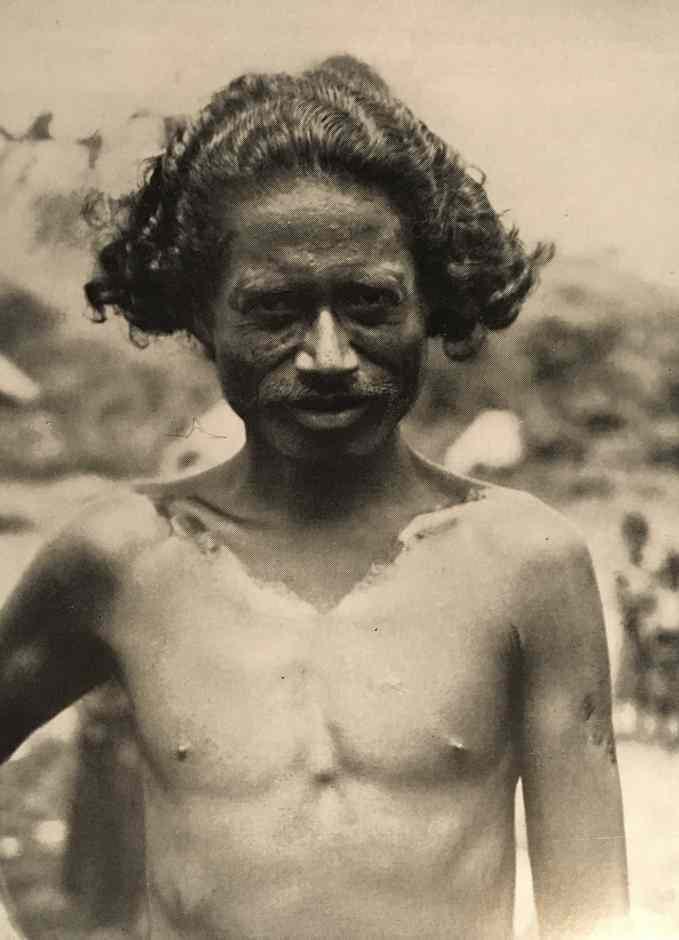

The people of Lobe Tobi seem more civilized, more impersonal and more humdrum than the rest of East-Flores. There is nothing to be felt here of the wildness and temperament of the Ili Mandiri residents or Bamanese. It is difficult to say whether this is a racial peculiarity, whether in them, as well as in the psychologically similar inhabitants of the western Maumere region, other elements of mixing further to the northeast are represented, or whether the influence of the mission, which has been here for much longer, has had a stronger effect. The Lobe Tobi area is almost completely Christian, only a few old people who can be counted on the fingers, have stayed away from the new teachings. There are only a few men with long hair and bare torsos, almost all of them already own a linen jacket or at least wrap themselves in a blanket, the selendang, which usually consists of European or Indian calico.

One of the few men in the heavily Christianized area of Lewo Tobi who is bare chested and has long hair. Vatter 1935.

Very little jewellery is worn, even the silver "bēIaung" ear pendants are very rare; tattooing is completely absent and reappears only on the west side of Lobe Tobi in the form of a small zigzag line between the eyebrows; the only common practice is teeth filing. By contrast, weaving and ikat technology have reached a remarkable peak here; only in South Solor and in some parts of Lomblem [Lembata] have we seen similarly rich, tastefully patterned and technically perfect cloths. Unfortunately, however, this ancient art is now in decline, the works of the younger generation cannot be compared with the creations of the past, of which numerous pieces are still found. The beautiful sarongs are almost all from grandmother's time, the young already consider ikatting "terlalu kerdja", "too much work"; The concept of "time" has come over people, they are starting to run out of time, and that is the end of the old craft culture. The most beautiful old sarongs are said to have required five, six, seven years of work! The new fabrics are simpler and artless and often already interlaced with garish European yarn.

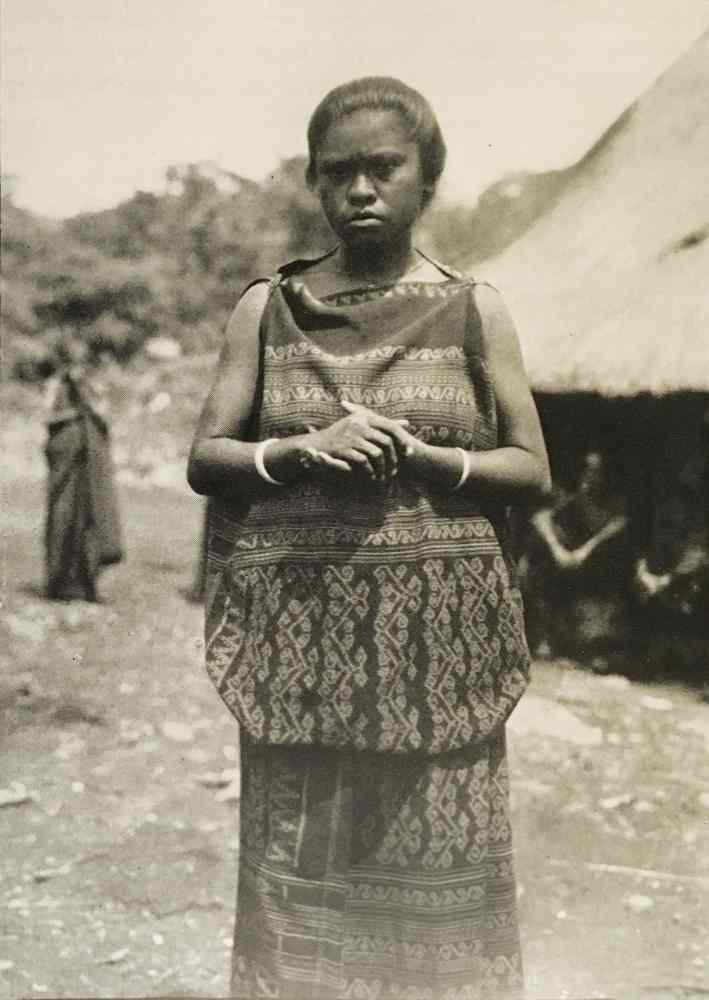

The textile technology is the same as in the rest of East Flores, only the hand spindle is almost completely displaced by the spinning wheel. The female sarong is very long and reaches down from the shoulders to the feet. Here you wear it differently from usual: pulled up to the armpit, pulled forward from the back over both shoulders and held together with a thorn, although now also with a safety pin. Wide and puffy it falls down over a narrow palm leaf belt. It is no longer a skirt; the way it is worn is reminiscent of a classical dress.

A woman in Lewo Tobi wearing a beautiful old ikatted sarong. The sarong is always pulled up at the front and back to cover the chest and is fastened over the shoulder with pins. Vatter 1932.

The emergence of private ownership of land, which fundamentally influences economic and social organization, can probably only be addressed as a consequence of mission and civilization. Only a small portion of the land is now firmly owned by the clan and is not for sale; much of the land is already divided among individual families as “näwanura” and can be bought and sold, even to members of other kampongs. Larger areas of land are already united in one hand and the contrasts between rich and poor are greater than usual in East Flores.

The office of Tuan tanah still exists, and the agricultural cult is still practiced, but with a very simplified ritual: it is an old custom, but behind it there is no longer the spiritual connection of earlier times. As with Ili Mandiri, there is a representational field, the "liwung", which in this region always seems to be the land belonging to the Tuan tanah, and where the individual works are performed together with prayer and sacrifice for Lera-Wulan and the earth:

"Lera-Wulan titi lodo, Tana-khan lali graha!"

"Sun-moon come down from above, earth come up from below!"

The rice maiden is called "luka erra", i.e. "Take the seeds out of the basket"; she is portrayed by a young girl or a married woman sitting in front of the sacrificial pole, as at Ili Mandiri, handing out the seeds to the women and girls. After sowing, a gourd plate with rice and fish and a coconut shell with palm wine are placed on a baleh in the house and the following prayer is addressed to the ancestral souls:

"Käwoko gon mään pä, tali tulun lau dai",

"You ancestors, eat and drink this, increase (the seed), help, come over the sea (from the island of the dead)!"

Hanna Vatter sitting on a dugout canoe, thought to be in Lewotobi

Return to Top

Dyeing and Weaving in Ilé Bura

As early as 1929, Ernst Vatter observed that the traditional craft of ikat binding and weaving in Lewotobi was already in serious decline. Women were no longer making the high-quality textiles that had been produced by their grandmothers.

Despite this, the craft of weaving has survived up to the present day, although now it is only practised by a small section of the female population. Yet it can still provide an important contribution to the family income. One elderly weaver in Lewo Tobi told us that she had been able to send all of her eight children to school thanks to the sale of her textiles. Today her daughter-in-law was selling her sarongs at Pasar Baru, located between Larantuka and Maumere.

We have already mentioned that weaving is confined to three coastal villages: Lewo Tobi, Lewouran and Riang Baring. Yet even here, many women no longer weave. In Lewo Tobi we were told that there are now only about ten weavers, out of which only around four were fully active. The group was headed by Mama Ella who suffers from bad rheumatism. Nevertheless there is now a village programme to re-educate women to weave. In neighbouring Lewouran there used to be an organised weaving group (kelompok) but it has since ceased to be active.

The one remaining weaving stronghold is Riang Baring, where there are still many women producing textiles, some working together in groups. There are three organised kelompok, one of which is kelompok Kaba Mare.

Although the overwhelming majority of textiles produced today are woven from synthetically dyed commercial cotton, some of the older weavers are still growing cotton in their gardens and are hand-spinning their own yarn, using both drop-spindles and spinning wheels. Some of this is used in combination with commercial yarn in the same textile.

Ginning raw cotton using a nalo

Above and below: Women in Riang Baring hand-spinning their own cotton yarn

We were informed that hand spinning with a wheel was quite common up to the 1980s and 1990s.

Local weavers refer to a gin as a nalo, while fluffing up the cotton fibres with a bow is called bulelu. A cotton puni is a lelu, while a spinning wheel is a mute. A niddy-noddy is a bla-ing.

After warping up, the warps are arranged in bundles or kenuma and stretched out on a wooden kageng binding frame. The pattern, which is recalled from memory, is then bound using strips of dried gebang palm leaf, harvested from the Cabbage Palm (Corypha utan).

Commercial cotton yarns bound with gebang palm leaf strips in Lewo Tobi

Natural dyes were used widely up to the 1980s but today are used only sparingly. Here indigo is called tau and morinda is called koré. Morinda grows around each of the villages and it is the job of the men to dig up the roots. Weavers say that they mix the koré with kroman, which is the leaf from a forest tree that grows higher up the mountains and is also sold by traders who come from Maumere. Kroman must therefore be the local name for loba (Symplocos).

Sometimes weavers also use the bark of the root of buka, which is clearly a different species of morinda. The roots are a yellow colour and produce a different shade of red.

A sample of the leaves and fruits of buka along with a piece of its root

Women make a natural grey dye and a chestnut brown dye using turmeric, kajo kuman (known elsewhere as kayu kuning) and lime, dyeing their yarns three times. They also make a green dye from crushed tomato leaves and lime. For a khaki green colour, they dye just one time using kajo kuman, turmeric, tomato leaves and lime.

After dyeing, the bindings are cut and the warp bundles are stretched on a kageng frame so that they can be adjusted to focus the pattern. The bundles are then locked in alignment by binding them to a narrow stick.

One interesting feature of this region is that many weavers use a long continuous warp that enables them to make two identical sarongs at the same time.

Above: A kageng frame inside a house in Lewo Tobi

Below: Synthetically dyed yarns stretched out of a frame in a house at Riang Baring

Many Lamaholot looms are short so that each panel of a sarong must be woven separately. In Lewotobi, weavers must extend the length of the loom so that they can weave four identical panels from a single long continuous warp.

Weaving a pair of synthetically dyed sarongs in Riang Baring

Return to Top

Vatter’s 1929 Textile Collection

In January 1929 Ernst Vatter collected nine textiles from Lewotobi – eight two-panel sarongs, which he labelled tenepa, and one selendang. These are now held in the collection of the Museum der Weltkulturen in Frankfurt. They provide a clear insight into what Lewotobi textiles were like over a century ago.

Interestingly the term tenepa is usually applied to three-panel Lamaholot sarongs and does not seem to be in use in the Lewotobi region today. Was this the indigenous nomenclature used at the time or simply a label applied by Vatter?

Vatter rated Lewotobi textiles highly, placing them on the same level as those from Ilé Apé and Lamalera on Lembata Island and those from neighbouring South Solor (1932, 214).

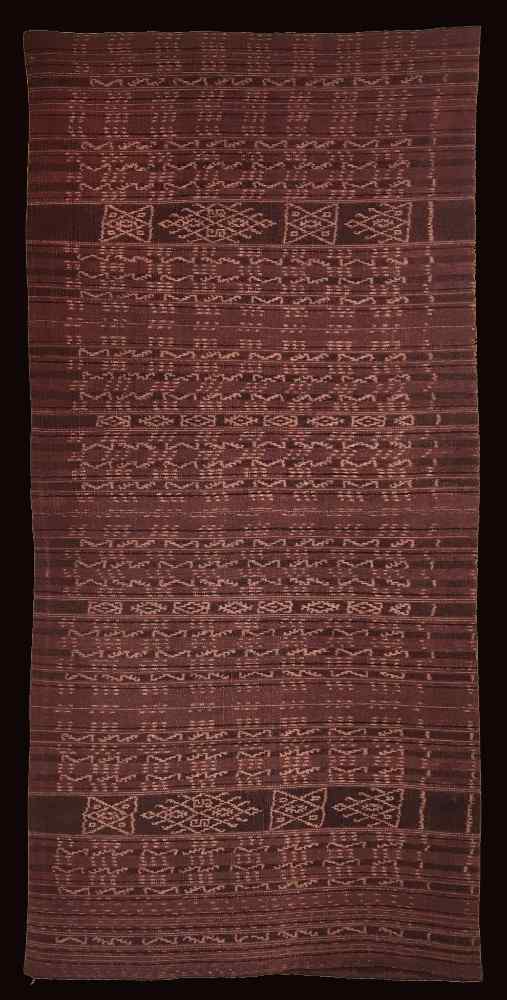

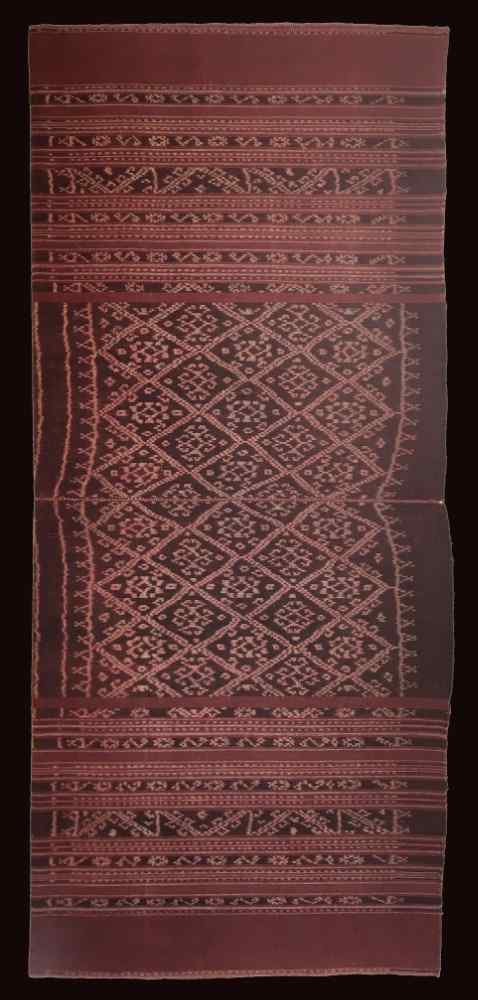

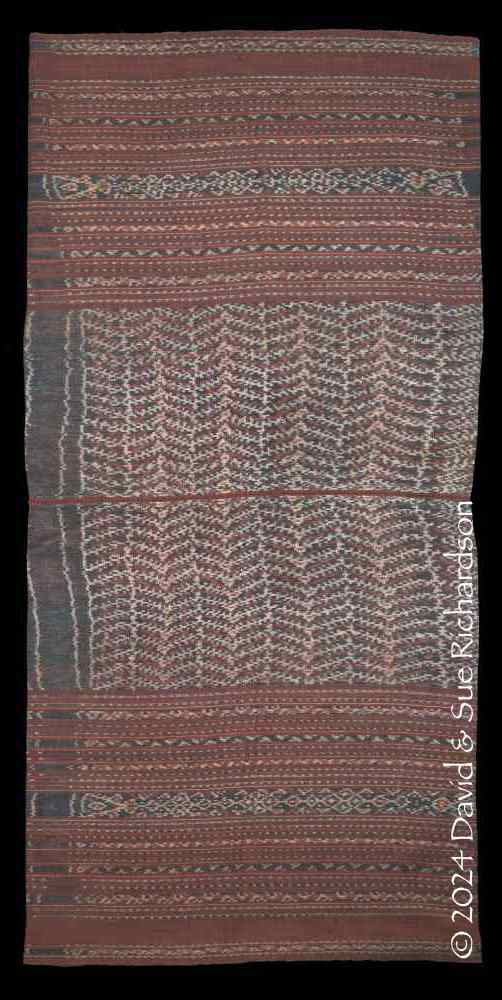

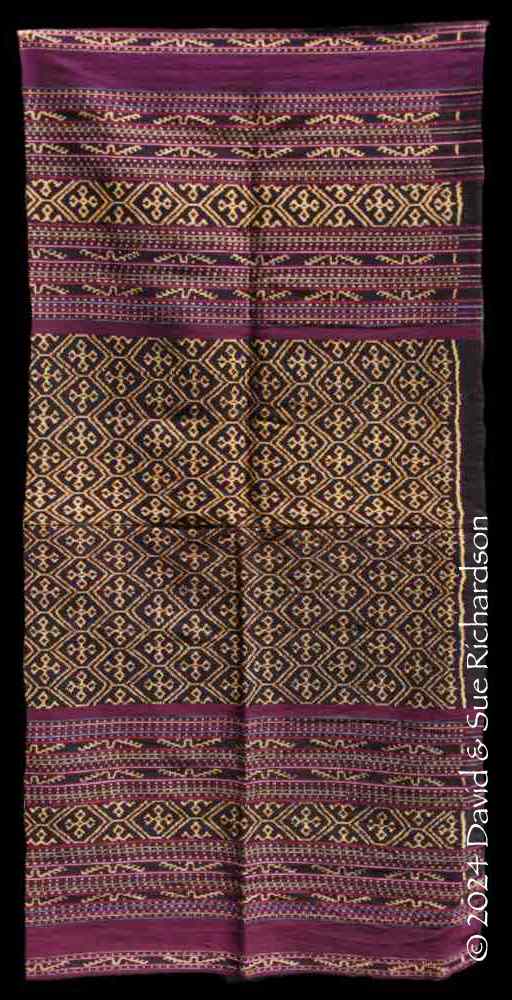

Vatter described the fine example he collected in Nurabelen, shown below, as a precious bridewealth sarong, noting that it had been dyed using the belapit process, with indigo overdyed with morinda. Although the sarong was two-panel, to his eye it had a three-panel appearance.

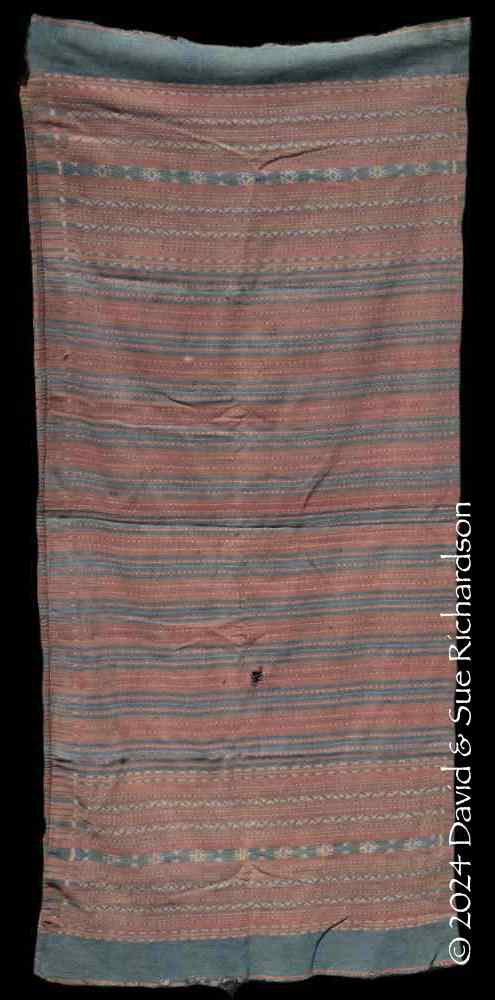

A bridewealth tenepa collected in Nurabelen

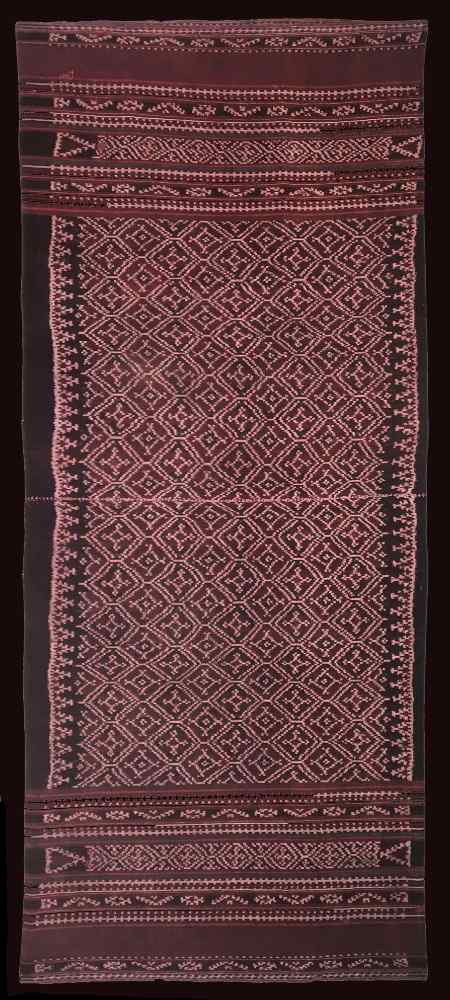

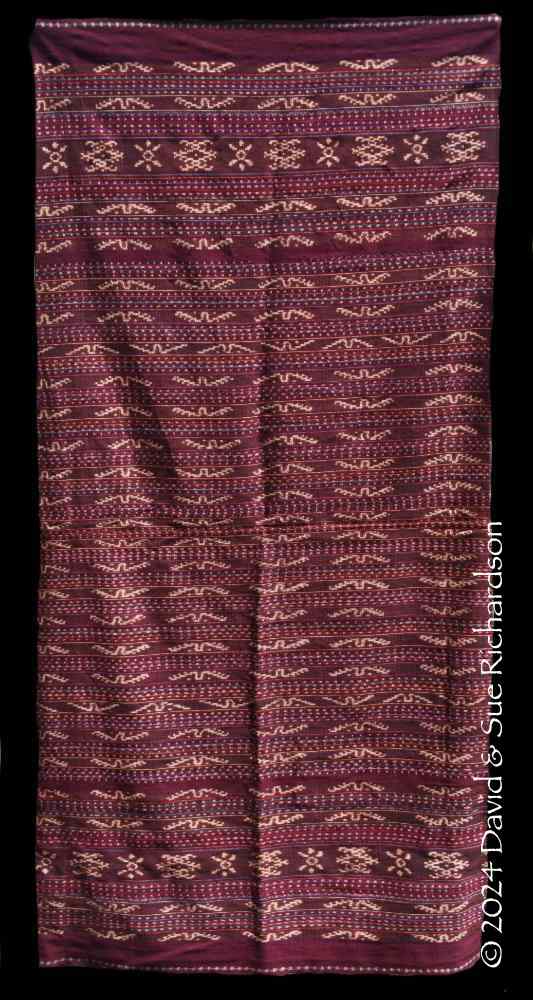

The second tenepa that Vatter collected in Nurabelen was rated as the most valuable type of bridewealth sarong to be found in that village. Both cloths from Nurabelen had been decorated with blue, green and yellow warp stripes.

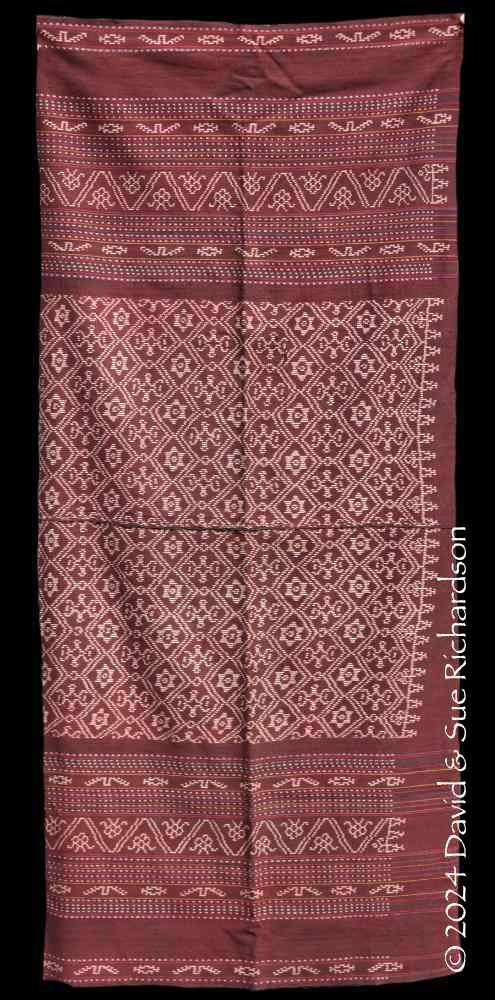

The second tenepa collected in Nurabelen

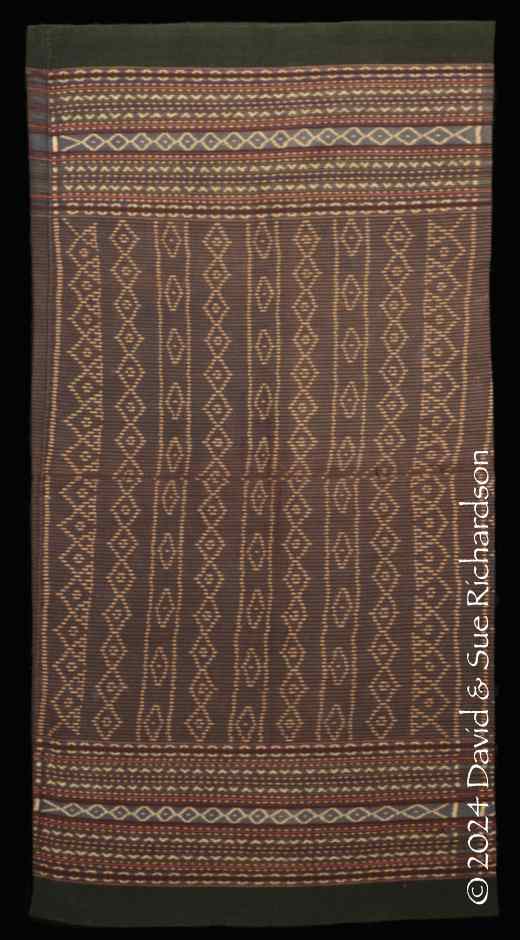

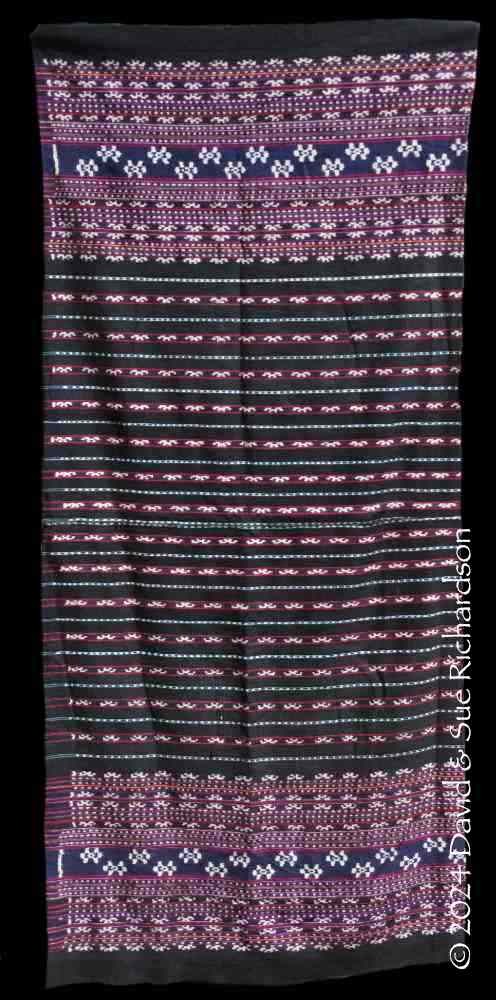

The tenepa that Vatter collected in Lewoawan (now Lewouran) was also considered as the finest and most expensive to be found in that village. Vatter noted that at the time of his visit, similar cloths of this quality could no longer be found.

The tenepa collected from Lewouran

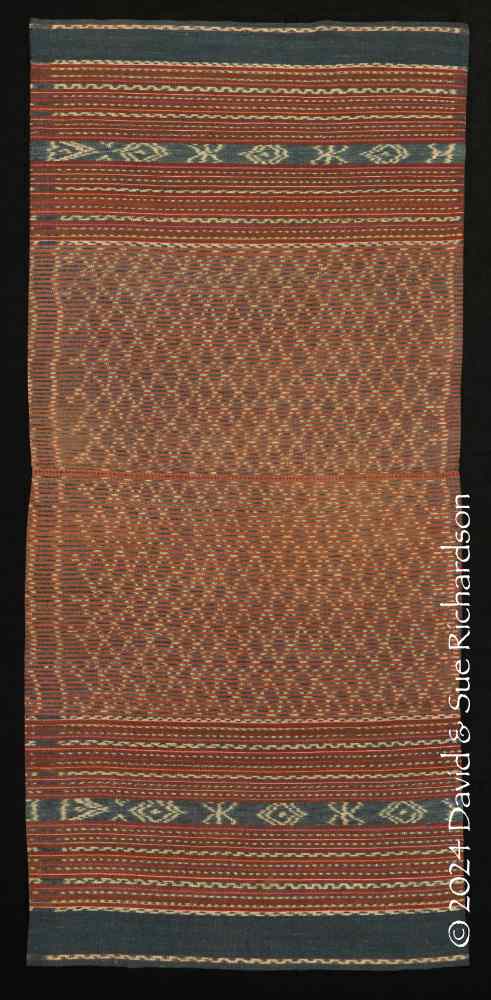

Vatter noted that in the following tenepa, collected in Riang Bunga, the pattern created the illusion of a wide, continuous centre field. It was decorated with red and green-blue warp stripes and had small green-blue highlights. The design is identical to the kwatek or fatek neppa woven in the Lewotobi region today.

The two-panel tenepa Vatter collected in Riang Bunga

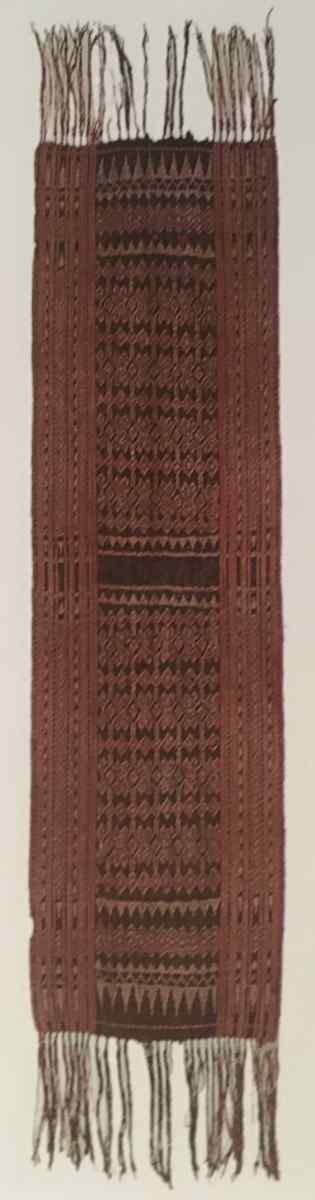

Vatter noted that a selendang he found in Lewoawan, today known as Lewouran, was already an old piece in 1929. He considered its pattern heavily influenced by Indian patolas and suggested that it possibly came from the Sikka region. However, it is identical to the antique nowi sashes found across the strait in Southwest Solor. They too have longitudinal mirror symmetry and long fringes. This suggests two possibilities. Firstly, the selendang could simply be an import from Solor Island. Alternatively, it may have been that the weavers of Lewotobi produced the same type of textile as was being made on Solor. Sadly, such fine textiles cannot be found in Lewotobi today.

An old selendang collected in Lewoawan (now Lewouran)

The nine textiles that Vatter collected from Lewotobi are unlikely to be fully representative of the full range of what was being made in Lewotobi in or before 1929. Nevertheless, these nine are remarkably varied and suggest there was considerable diversity in the sarongs that were being made in the region at that time.

Return to Top

Ilé Bura Textiles Today

More recent Ilé Bura textiles are still amazingly varied. Not only do the designs vary from kampong to kampong but in some instances so does their nomenclature.

Just like those collected by Vatter, all of the sarongs made in this region today are two panel. Some of them have close similarities to the tenepa found in 1929. However, today the women’s two-panel skirt is locally known as either a kwatek or a fatek, both terms pronounced with a silent k.

Many are woven with a layout in which narrow strips of ikat alternate with plain warp stripes. This fragments the pattern, creating a softer effect than if the motifs appeared complete on a plain ground.

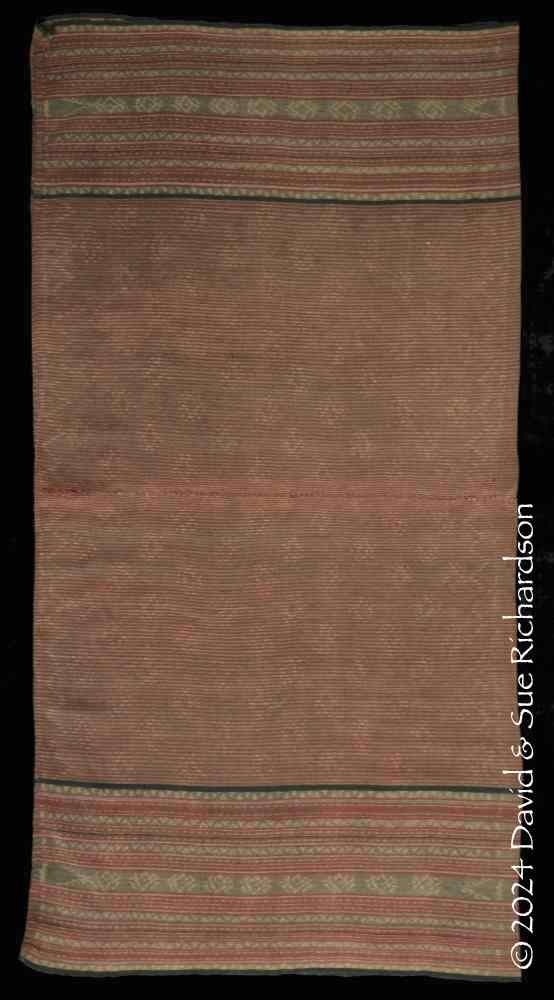

Some of the textiles woven in the Ilé Bura region of East Flores were traded to the adjacent region of Tana ‘Ai in Sikka Regency where there was no tradition of ikat binding. There the local people, the Ata Tana ‘Ai, believe that in the past, customary law forbade their women from weaving. It was said that those who dyed or wove would be cursed by si Nitu (gods) and their actions would lead to famines or plagues.

The following example, made in the Ilé Bura region, had been owned by the same family in Tana ‘Ai for 55 years so is probably 65 to 85 years old.

A kwatek plika from Tana ‘Ai. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Kampong Lewo Tobi Textiles

The simplest types of sarong made in Lewo Tobi have simple striped centre fields and are called kwatek pruang, pruang meaning sandwiching. The central field is sandwiched between the upper and lower clusters of narrow bands, which are known as the kenuma heba. The heba are the end sections and the kenuma are the ikatted bundles that make up the narrow ikat bands.

A kwatek pruang owned by Maria Ina Kedang from suku Kedang

Kwatek with ikatted centre fields are locally known as a kwatek plika. The term plika refers to the traditional motif used on these sarongs, which symbolises a traditional cooking hearth with the pot placed on the fire supported by three stones. This has become the generic term for an adat sarong, even if it is not decorated with the plika motif. However, when such a sarong is worn for a traditional adat ceremony it is referred to as a sugi.

There are five types of kwatek plika:

- kwatek plika praka (diamond)

- kwatek plika klegu (snake’s way)

- kwatek plika wuno geré (morning star)

- kwatek plika nuhu (pounded rice)

- kwatek plika layang-layang (kites)

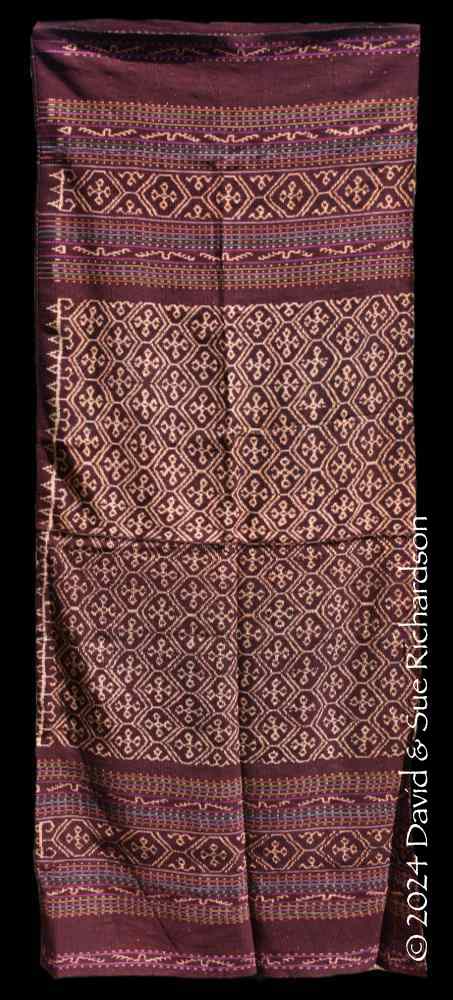

A kwatek plika praka woven in 2007 by Maria Ina Kedang in Lewo Tobi

Richardson Collection

We were told that each of the eight clans in Lewo Tobi has its own pattern(s) and other clans cannot copy them.

The first kwatek plika illustrated below is owned by the weaver Weka Kedang who belongs to suku Kedang. The centre field is decorated with rows of diamond-shaped praka motifs mixed with rows of star-shaped motifs.

A kwatek plika praka owned by Weka Kedang from suku Kedang

The next two kwatek plika were made by weavers belonging to suku Witi. The first has large diamond-shaped praka motifs while the second has zigzag columns representing the path of a snake. The crumpled appearance of these sarongs illustrates how badly they have been stored by their owners.

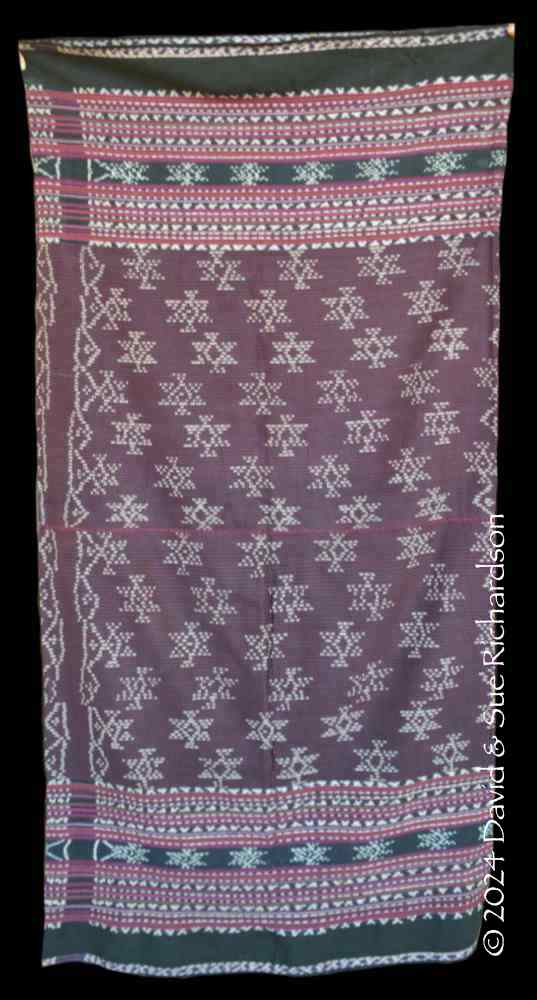

Two kwatek plika made by Lewo Tobi weavers from suku Witi

Above: a kwatek plika praka; Below: a kwatek plika klegu

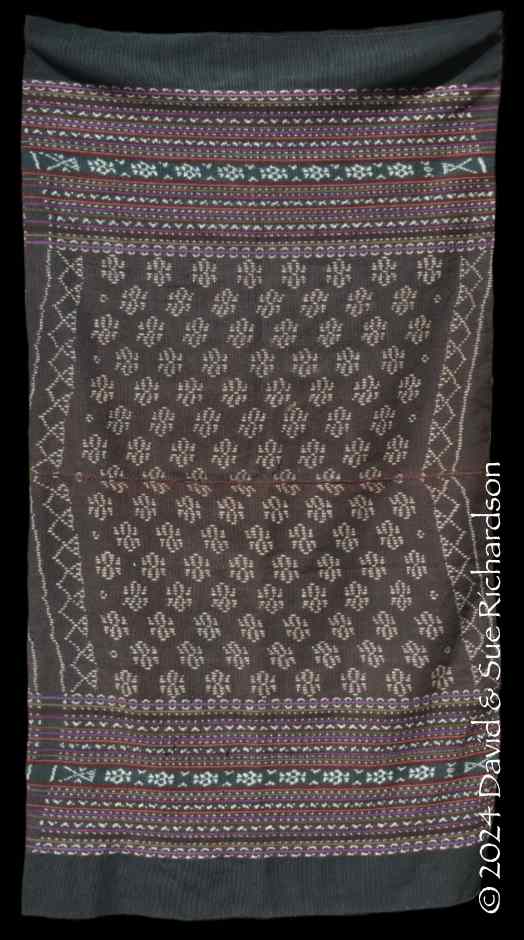

The fifth example has a central diagonal lattice of star-shaped motifs while the final example has a central diagonal lattice of hexagon-shaped floral motifs.

Above: A kwatek plika wuno geré

Below: A kwatek plika praka with the bunga lolon motif owned by Maria Ina Kedang

Return to Top

Kampong Lewouran Textiles

Weavers in Lewouran produce a very wide range of different textiles, including a number of simple everyday sarongs.

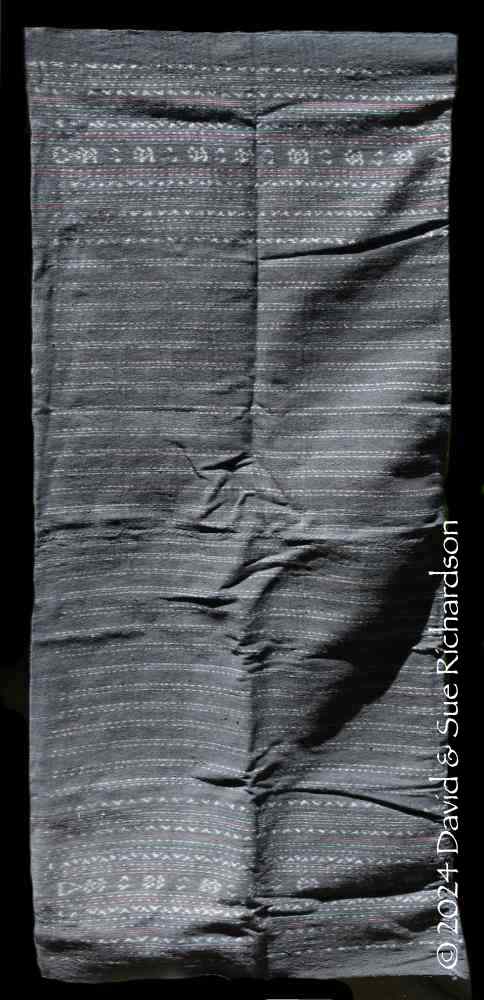

The most basic is the kwatek kenuma mowak eha, which has a plain striped centre field and end sections (hebe) with the simplest narrow ikat stripes composed of just one (eha) mowak - a cluster of ikatted bundles or kenuma. The kwatek Kedang is similar but has narrow ikat bands in the end sections. In the past these were dyed with indigo but more recently with synthetic black. It is very similar to the kwatek pruang of Lewo Tobi.

Above: A kwatek kenuma mowak eha made by Yuliana Jeda from suku Leba

Below: A kwatek Kedang made by Teresia Pao Uran from suku Uran

The kwatek Lamakera is a slightly more complex everyday sarong with many narrow ikatted stripes in the centre field. It was dyed with both indigo and morinda. It is named after a village located at the eastern tip of Solor Island.

A kwatek Lamakera also made by Teresia Pao Uran

The kwatek kenuma has a wider band of ikat in the end sections and slightly bolder ikat stripes in the centre field. The latter are decorated with the eko keppei bird-wing motif (eko = bird and keppei = wing).

A kwatek kenuma woven by Mama Yuliana Jeda

Weavers in Lewouran also make the kwatek plika, just like the ones found in Lewo Tobi.

The first naturally dyed example was made from a mixture of hand-spun cotton and two-ply rayon by Nenek Maria Kung Kwure from suku Kwure. She told us that wove it before she was married at the age of 20. As she was over 80 years in 2023, it must therefore have been made around 1960.

Above: The kwatek plika woven by Maria Kung Kwure. Richardson Collection

Below: Maria Kung Kwure with her kwatek plika

The following modern examples were woven in 2019 by Mama Yuliana Jeda. The first is decorated with the wuno geré star motif.

Above and below: Two different kwatek plika woven by Mama Yuliana Jeda in 2019

It seems that local weavers also still make a kwatek neppa similar to the ones found in Riang Baring (see below), but we have yet to see one in this kampong.

One of the more unusual designs in Lewouran is the kwatek lusi lerang, decorated with the lusi lerang or flying eagle pattern, based on the locally found Spotted Eagle. The design is claimed to be specific to this village. It is worn for performing the Eagle Bird Dance in which an eagle waving its wings collects the newly returning warriors from the battlefield.

The following hand-spun example was woven by Monika Jawa Muda from suku Muda, who died in 1988 aged over 70. Her daughter informed us that it was woven when her mother was aged 50 and she was still in elementary school, which must have been some time prior to 1968.

The kwatek lusi lerang made by Monika Jawa Muda sometime prior to 1968

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Kampong Riang Baring Textiles

All of the sarongs made in Riang Baring are two-panel. Local weavers refer to them as fatek (pronounced with a silent k) rather than kwatek. There are four main types that are classified by status: two being for everyday use and two being ceremonial adat sarongs. Weavers informed us that in Riang Baring all of the patterns belong to the village not to the individual clans.

The fatek oiken is the simplest everyday sarong, mainly decorated with plain warp stripes and warp stripes ikatted with dashes.

Nenek Agnes Timu Mare wearing a simple naturally dyed fatek oiken

The fatek togen (pronounced ‘togun’) is a somewhat similar everyday sarong with an indigo centre field crisscrossed by plain and simple ikatted warp stripes and end sections composed of a closely spaced cluster of similar warp stripes. Fatek togen seem to be quite widely worn today. Smaller versions are made to be worn by young girls.

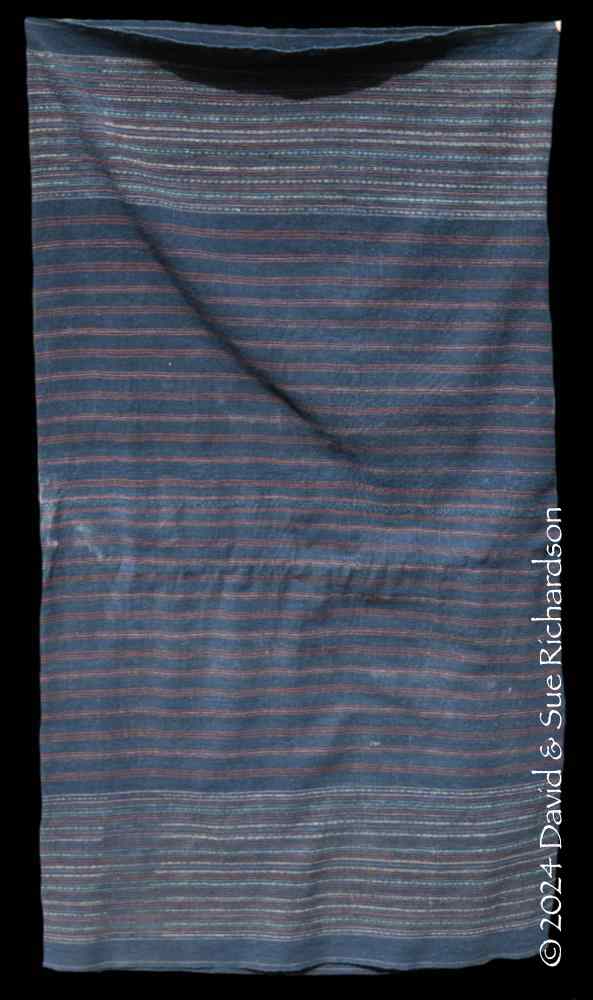

The hand-spun example below was woven in 1995 by Mama Getrudis, who is a spinster living in Riang Baring with her married sister. However, the threads were bound and dyed by 97-year-old Nenek Agnes Timu Mare from suku Mare (shown above), the mother-in-law of Gertrudis’ sister.

Above: The fatek togen woven by Mama Getrudis. Richardson Collection

Below: A threadbare chemically dyed fatek togen made in 1980

The fatek mowak has dominant ikat bands in the end sections and a centre field filled with narrow ikatted warp bands decorated with the eko keppei bird-wing motif. Such sarongs were worn by dancers who perform with outstretched arms holding a sash which they flap like the wings of a hovering eagle. Today however most dancers prefer to wear the fatek neppa instead.

Above: A fatek mowak woven by Madelena Wunga Darang

Below: A recently woven fatek mowak

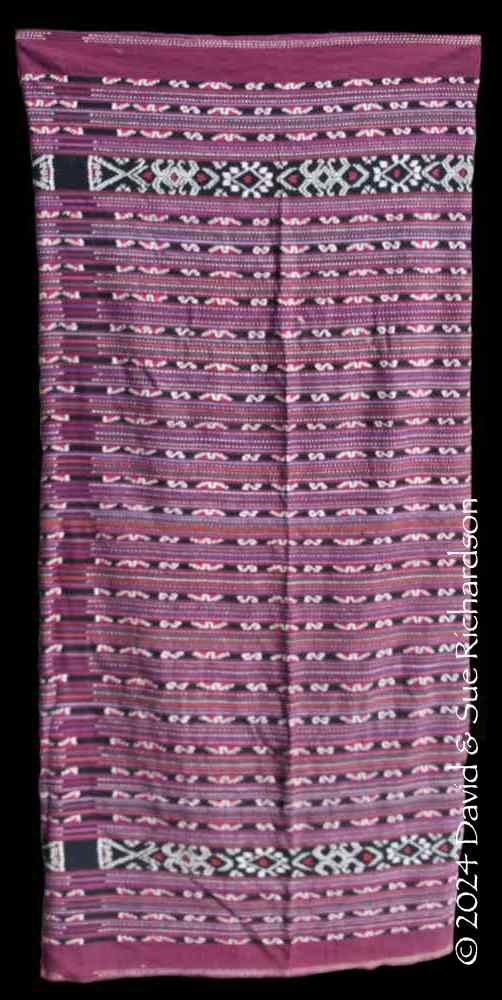

The distinctive fatek neppa has a central lattice of hexagons enclosingwaibulun various small motifs, such as crosses, hooked diamonds or stars. Traditionally they were only dyed with morinda. They are typically worn for adat ceremonies. In the past only the nobility was permitted to wear them.

There are two main types:

- The fatek neppa heranawa has a cross shaped motif with small diamonds at the end of each arm. The motif is called kroko, and symbolises the flower of a wild grass that has a white leaf and grows up to five feet tall.

- The fatek neppa waibalun (named after the village of Waibalun adjacent to Larantuka which has a terminal for the ferry to Kupang) has a hooked diamond motif called the crab or kujo motif.

More recently, new designs of fatek neppa have appeared decorated with star-shaped or floral motifs.

Above and below: Two modern versions of the fatek neppa heranawa with the kroko motif

Today fatek neppa are almost universally the preferred costume of local dancers, as illustrated below.

Dancers from Riang Baring wearing fatek neppa sarongs and manuk aing chicken feather headdresses

Above: Cecilia Dominica, known as Lilis, dancing at the Festival Tenun Ikat in Larantuka in 2019. Below: An image of Cecilia Dominica’s complete fatek neppa waibalun

However, fatek neppa are also worn for non-ceremonial occasions, such as informal social events

Women wearing fatek neppa at a morning gathering of weavers and spinners

The men of Riang Baring dress almost exclusively in western clothing for everyday wear. However, they do wear a male sarong for adat ceremonies, which is known as a sae. These are simple textiles decorated with lighter coloured warp stripes. There are two types: the black everyday sae mité and the red ceremonial sae méan. These were naturally dyed in the past but are synthetically dyed today.

Male dancers wearing modern sae méan

The most important ceremony in Riang Baring is the annual Gemu Ramu ritual, which has two objectives: to cleanse the village and to seek the support of the ancestors for a good harvest. The ritual is led by local shamen known as molan, who begin by entering the forest to gather the leaves and roots of medicinal wild plants. On returning they perform the wede war dance symbolically fighting with the chiefs of the evil spirits. After the dance, the molan conduct a ritual blessing at the village temple and this is followed by prayers and a ritual feast. At the end of the ceremony, the processed medicinal plants are distributed to all the villagers to drink, thus ensuring their health and wellbeing.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2022. Flores Timur Dalam Angka 2022, Larantuka.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. East Flores Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden: textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, Hamilton, Roy W., (ed.), pp. 171–191, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 2004 Ostindonesien im 20. Jahrhundert: Auf den Spuren der Sammlung Ernst Vatter, Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt.

Justus M. van der Kroeff 1954. Disorganisation and Social Change in Rural Indonesia, Rural Sociology, vol. 19, pp. 161-173.

Martina, K., Nur Iswantara and Simamora, R. M., 2022. Nilia-nilia pendidikan karakter tari lusi lerang di desa Riangbaring Kecamatan Ile Bura Kabupaten Flores Timur, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Institut Seni Indonesia, Yogyakarta.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 1 February 2024.