Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Nggela Weaving Community

Nggela Ecology

Local Cotton and its Preparation

Commercial Cotton and Synthetic Yarns

Warping Up and Binding

Indigo Dyeing

Morinda Dyeing

Other Natural Dyes

Synthetic Dyes

Unbinding and Starching

Assembling and Focussing

Final Starching

Weaving in Nggela

Loom Terminology

Sewing Up the Sarong

The Complete Weaving Process

Women’s Sarongs

Lawo with Centre Panels

Lawo with Vertical Bands

Lawo with Horizontal Bands

Lawo with a Complete Covering of Motifs

Lawo Butu

Men's Textiles

Luka Sarongs

Luka Shoulder Cloths

Bibliography

Weaving in Ende Regency

Historical References to Endenese and Lio Textiles

Samuel Roos 1877

Herman ten Kate 1891

Max Weber 1899-1900

Johannes Elbert 1912

Charles Le Roux 1915-1919

Bertho van Suchtelen 1921

Elisabeth Wilhelmina Viruly Verbrugge 1922

Father Simon Buis SVD 1923

Raymond Kennedy 1949-1950

Roy Hamilton 1989

Willemijn de Jong 1987-2022

Conclusions

The Nggela Weaving Community

Local villagers have informed us that there are approximately 300 weavers in the entire kampong, including the surrounding houses.

Some of the weavers in Nggela, photographed in 2017

Some years ago, in a move to support the important weaving centre of Nggela, the local government established a cooperative for the whole village called Kelompok Mamo Nggela, mamo referring to the grandmothers and ancestors. Over time this has fragmented into around 23 to 25 smaller kelompok (groups), the majority of which are about the same size. Some are more active than others.

Some of the more notable are:

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kaipere Lesu Usu (Open the Door).

- Kelompok Kema Sama (Cooperation)

- Kelompok Sadar Diri (Self Aware)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Mawar (Rose)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Tunas Baru (New Shoots)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Nara Suru II (Want to know something)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Ola Muri (Your Life)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Gemar (Like)

- Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kéli Mara

One important group has been Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kaipere Lesu Usu. In 2013, the head of the cooperative was Teresia Sarah, the secretary was Rosa Dalima Sina and the accountant was Regina Galle. Some of its members include Ibu Seli, Ibu Flor, Mama Teresia, Fransiska Ngaku, Elisabeth Pango, Gertrudus Nae, Anastasia Teke and Veronika Riri.

n

From left to right: the head of Kelompok Tenun Ikat Kaipere Lesu Usu, Mama Teresia Sarah, Mama Rosa Dalima Sina, and the accountant, Regina Galle

Another very active group was Kelompok Kema Sama in dusun Wawo Lambo. However by 2023 this had shrunk to just two members, one of whom is the master dyer and binder Mama Fransiska Yasinta Mbaru.

Above and below: Kelompok Kema Sama

Kelompok Sadar Diri, located close to the church, was previously divided into two parts, Sadar Diri I and Sadar Diri II. These have since merged and now have about 8 to 10 members.

Some of the members of Kelompok Sadar Diri

Kelompok Tenun Ikat Mawar closed some time ago and merged with Kelompok Sadar Diri.

Kelompok Gema is headed by Terasia Landa and currently has 14 members.

Kelompok Kéli Mara is headed by Mama Yustina, known as Mama Yus, and has 10 members.

The signboard of Kelompok Tenun Ikat Nara Suru II

Return to Top

Nggela Ecology

Regarding the southern coastal region of Central Flores, including Ende, J. G. F. Riedel noted in 1886 that:

The land, which is of very varying aspect, is exceedingly fertile. On the higher parts the Coffee-tree will thrive luxuriously, while, in the lowlands, Kalapa [coconut], Tobacco and Kapas [cotton] can be constantly cultivated with success (1886, 66).

Nggela is located on a small plateau situated some 180m above sea level, and about 1km inland from the coast. The land to its north rises steadily up to the foothills of the dormant volcano Kéli Bara (1731m).

Lowland evergreen rain forest thrives along these southern coastal hill slopes. They are kept moist during the dry season by the southeast trade winds, which shed their limited moisture on the first hills that they encounter after crossing the ocean from Australia (Monk et al 1997, 234). Many patches of forest surrounding Nggela have been cleared for shifting cultivation and then left to fallow, allowing the secondary growth of thickets of herbs and climbers.

Above: The coastal landscape just east of Nggela

Below: The rocky coast at Ngalu Polo looking west towards Ende

The local tropical climate has two seasons - the dry season (June to October) and the rainy season (November to March). The area's relative humidity ranges between 70% and 90%. Winds are moderate and generally predictable, with monsoons blowing in:

- from the south and east in June through September (the dry east monsoon), when dry winds blow in from the Australian continent, and

- from the northwest in December through March (the wet west monsoon), when moist winds arrive from the South China Sea, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean.

During the dry season indigenous tree cotton, Gossypium arboretum, grows well in open areas of these hot, dry hills slopes. Some even grows in front of some of the village houses. Because of its inherent ability to withstand drought, and its poor tolerance to waterlogging, the cotton plant prefers this drought-prone environment. Cotton requires some rain during the planting period, but drought is essential during the latter growth phase – especially during the harvest when rain can wash away fibres and encourage rot.

Weed-like indigo also thrives in this environment in open areas and on the margins of woodland. Even within kampong Nggela, indigo grows wild around the houses and graves and in crevices along the walls.

Above and below: wild indigo growing in the centre of kampong Nggela

The location and climate are also ideal for the growth of morinda, Morinda citrifolia, which grows wild from sea level up to an altitude of 500m. It is also drought-resistant, and can easily withstand a drought of six months or more. Wild morinda can still be found widely in the surrounding area. The preferred variety is Morinda citrifolia var. bracteata.

Return to Top

Local Cotton and its Preparation

In the distant past, locally grown cotton was widely used in Nggela and most of the women there could process and spin it.

The availability of wild cotton (kapas) was always insufficient for the village’s weaving needs, so in the past cottonseed was recovered from the raw cotton and planted in local gardens during the rainy season between December and February, and harvested in the dry months of August and September. However during the 1930s, the increasing availability of commercial machine-spun cotton meant that many women no longer needed to plant cotton. This soon changed after the onset of war when imported commercial cotton became scarce. After the Japanese invaded in 1942, the occupiers made the cultivation of cotton compulsory. Cotton cultivation and hand-spinning continued across Flores into the 1960s due to the economic uncertainties of the Sukarno era. Under Suharto’s New Order regime, yarn imports finally revived, leading to the erosion of cotton-growing and hand-spinning (Hamilton 1994, 54). By 1979 the transition to commercial yarn in the Ende and Lio weaving districts was almost complete (Maxwell 1980, 143).

Today only a small amount of cotton is cultivated in Nggela. Now every weaver is using commercial cotton, although there are several elderly women who can still drop spin cotton, and several others who can process cotton fibre and spin it using a wheel.

The first stage is to clean and separate the cotton, a process called pili wara. The cotton bolls are first dried in the sun for a day and are then de-seeded using a wooden ngeu gin, which has counter-rotating rollers that pull the fibre away from the cottonseed, allowing the cotton fibre to be collected in a palm leaf basket. The cotton fibre is then cleaned by hand.

Paulina Hawo from Sa’o Labo operating her ngeu gin on a grave outside her house

However, handling the cotton tends to compress the fibres so they need to be fluffed and aerated. This is done by plucking the bowstring of a bamboo wo'o bow just above the fibres with a pick or finger nail so that the vibrations separate the individual fibres and shake off the dust and dirt. An alternative is to winnow the fibres by beating them with one or two thin wooden sticks.

Bowing raw cotton fibre in Nggela

Although the cotton fibre can now be spun using a drop spindle, known as a gai’e, in Nggela it is always spun using a locally made hand-operated jata spinning wheel. This consists of a heavy plank of wood fitted with an upright post with a horizontal axle at the top that supports the wheel. The latter is made from two parallel discs with outer rims of bamboo held in place by wooden spokes. A string is then criss-crossed betwen the outer edges of each disc to support the drive cord.

Such wheels are generally found in locations close to important colonial trading centres such as Sikka Natal, Ende and Larantuka, where they had been imported by traders during the seventeenth century. In preparation for spinning, the cotton fibres were rolled by hand on a flat surface into a cigar-shaped puni onto a thin, short length of sorghum stalk. A puni, known in the Lio language as an el'o, is the cotton equivalent of the woollen rolag.

Rolling cotton puni

The spinner sits beside her spinning wheel, holding the puni in her left hand. The fibres are gradually fed out between the thumb and forefinger to be twisted by the rotating end of a short wooden spindle known as the gai. This is driven by a tight cord wound around the spoked wheel operated by the right hand. The end of the spindle is supported between the big toe and the toe next to it. Once the spun yarn is sufficiently twisted, the length of spun yarn is allowed to wind onto the wooden spindle and the process is repeated.

Above: Mama Sia demonstrating how to spin using the jata spinning wheel

Below: Mama Vefa with her spinning wheel. Note the four unspun puni lined up on the base of the jata

Mama Ino spinning without the use of her foot

A spinner from Nggela showing how the spindle is held between the toes

Once the spindle is fully loaded with spun yarn (lelu), the latter is unwound and then wrapped around an H-shaped wooden niddy-noddy called a lai, which tensions the yarn and sets the twist.

Return to Top

Commercial Cotton and Synthetic Yarns

Today the weavers of Nggela universally use commercial machine-spun yarn, rather than hand-spun yarn, and it is generally purchased from the market in Wolowaru. However today the majority of this is in in the form of rayon rather than cotton.

On Flores commercial cotton yarn was imported to the main colonial ports of Rio, Ende, Maumere and Larantuka. Initially it was seen as an expensive luxury product, restricted to the nobility, but by the 1930s it was more widely available (Hamilton 1994, 54). In Nggela weavers were routinely using factory-produced cotton thread for the warp during the 1930s, while continuing to hand-spin yarn for the weft (de Jong 1994, 223).

Since the second half of the 1960s, Nggela weavers have exclusively used machine-spun thread, which has been increasingly acquired in the form of rayon (de Jong 1994, 213).

Commercial 2-ply cotton tends to be purchased in the form of finer yarns with a high yarn count, such as 40/2. It is purchased in plastic bags of skeins that must first be placed on a swift, known locally as a woe or wo’ae, and rolled into balls (nbodhe) in preparation for warping up.

Mama Gasi winding a ball of black commercial yarn from a swift at Kelompok Kema Sama

Balls of commercial yarn belonging to Mama Ango kept in a commercial cotton plastic bag

Viscose rayon yarn is generally purchased in two colourways, white and yellow/orange, the choice depending on what type of effect the weaver wants to achieve with the undyed motifs. The Nggela weavers call this rayon yarn bordir. The two colours produce very different-looking textiles, the white rayon appearing more traditional while the yellow/orange rayon gives rise to textiles with an unattractive artificial yellow caste. Although viscose rayon has a silk-like feel, it is made from wood pulp, so it has similar properties to cellulose fibres. The main brand sold at Wolowaru is Fanny Collection Tri-Warna.

A bag of Tri Warna 2-ply viscose rayon

Return to Top

Warping Up and Binding

The process of warping-up is called go’a, while the warps themselves are called lebue. Warping-up is done on a rectangular frame made from wood and bamboo known as an ugo or igo. Balls of yarn are placed in a container, such as a bowl or half coconut shell, and passed back and forth, wrapping the warps around the upright ends. The latter are sometimes lined with palm leaf to protect the yarn from catching on the rough wooden beams. The palm leaf also makes it easier to move the warps up and down.

There are two types of ugo – a wide one and a narrower one. The width of the wide ugo is sufficient to hold enough warps to weave two identical panels of a tube skirt. These are normally the outer panels of the three-panel sarong. Because the warps are wound in a circular movement, those facing the weaver will produce one panel, while those on the back will produce a second. Because all Nggela sarongs have three panels, the warps for the centre panel must be wound separately on the narrower ugo.

A wide ugo frame on a veranda in Nggela, wound with yellow rayon warps

Normally one bundle of yarns, known as a gami, is wound at the same time and can be composed of 4,5 or 6 yarns, although 6 tends to be the most common. The number of loops depends on the type of textile to be woven, and the width of its ikat bands. Thus one half of a band to be decorated with the pundi motif would require 90 gami.

A pair of coloured cords are laced around the individual yarn bundles so they can be easily separated for binding.

Nggela weavers sometimes make two identical sarongs at the same time. This is done by layering one set of warps over another, so that they can both be bound at the same time.

Mama Ango warping up using three balls of cotton.

Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

Warping up at Kelompok Kema Sama, using six balls of orange viscose at a time

Once the warps have been fully wound, they are ready for binding, still using the igo frame. First the bundles are grouped into individual ikat bands and the warps are locked in alignment. This process is called tu’é. This is best done by placing a thin short stick, a kayu tu’é, across each band close to one of the end beams of the igo and tying the bundles tightly to it with cotton yarn. In some cases, however, the stick is omitted and the bundles are just locked with loops of yarn – see below.

Two warp bands in which the bundles have been locked with cotton yarn and separated using a blue plastic tape

Now the bundles are ready for binding, a process known as tege. The bundles are bound in pairs, with the front bundle paired with is corresponding bundle to its rear. In this way the ikat bands on two panels can be completed with just one binding.

As with most Lio ikat producers, Nggela artisans bind their warps using fine strips of dried coconut palm leaf, which is known as lavinio. Endenese producers generally use strips of dried cabbage palm leaf, known as gewang. The strips are cut from each single leaf using a very sharp knife and then hung up to dry. Today some weavers prefer to use plastic string.

Pairs of young fresh coconut leaves, right, and pairs of coconut leaves that have been cut into narrow strips and dried, left

Before tying they wet the dried strip of coconut leaf with water to make it supple. The patterns are bound from memory, the bundles being tied with knots that have a long tail.

Above: Binding the pattern using coconut palm fibre

Below: A set of warps bound with the octagonal patola-inspired sémba motif

Binding yellow rayon gami arranged into separate bands

After binding, the warps are released from the igo binding frame and are ready for the first dyeing stage. For naturally dyed textiles, indigo is dyed first and morinda is dyed second.

Return to Top

Indigo Dyeing

Many women in Nggela know how to dye indigo, and almost every weaver has a dye pot under her house. There are also a few specialists, one of the most experienced being Teresia Korse who is married to Raymondus Ada.

While indigo is called tarum, the process of indigo dyeing is called nggili, or as Teresia Korse describes it, podo nggili, the podo being the small pottery container that holds the dye bath. These pots are made locally.

Teresia uses about eight separate dye pots, located on the ground below her house where they are sheltered from the sun. Each one is filled with fermented indigo leaf mixed with lime powder that has been added in small cups. No other ingredients are used. Teresia takes each skein of yarn and dips it in one pot after the other, wringing it out in between.

Mama Teresia dyeing skeins of cotton in her indigo pots

Above and below: The ceramic indigo dye pots

Squeezing the hanks of cotton in the thick indigo dye paste

As a general rule, indigo is dyed about four successive times, the yarns being left to thoroughly dry in between. When not in use, the filled pots are covered with the dried sheaths of palm tree fruits to prevent excessive aeration and oxidation of the leuco-indigo.

For more information about indigo dyeing in eastern Indonesia, view our indigo webpage.

Return to Top

Morinda Dyeing

The Lio of Ende Regency refer to morinda as kembo. In the past it was used extensively, but now only a limited number of women can process it and dye with it.

The harvesting of morinda root is a labour-intensive activity, with the weavers receiving help from their husbands or other male relatives.

Mama Ango and her husband harvesting morinda root and stripping off the bark.

Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

The first stage in morinda dyeing is known as oiling, locally called mina. This involves pre-treating the yarns with an alkaline lye made from wood ash, crushed candlenut and the powdered leaves and bark of the Symplocos tree (Hamilton 1994, 65). Candlenut is known as kemiri, ash water as awu waja, awu being ash, and Symplocos as loba.

Mama Ango oiling her indigo-dyed yarns. Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

After the indigo-dyed yarns have been left to steep in the crushed candlenut mix for some time they are then left to dry in the sun and kept for up to three or more months.

For the next stage, dyeing with morinda, the dried morinda root must first be crushed into a powder by pummelling it in a wooden mortar - a strenuous task.

Above: Mama Ango crushing her dried morinda root in a wooden mortar. Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

Below: Some crushed morinda root in a palm sheath container.

To prepare a morinda dye bath handfuls of the crushed root are added to water, along with some powdered loba but without the addition of ash water. The loba is bought in powder form from Detu Keli, which is 40km from Moni on the right side on the way to Ende and 30km from Wolagai. In 2018 it cost Rp. 40,000 for a small cupful.

A plastic container filled with powdered loba purchased for Rp. 100,000

The morinda pulp is repeatedly squeezed to ensure that all the morindin dyestuff is extracted from the root and dissolved in the water. Now the yarns can be immersed in the dye mixture and pressed with the fingers to ensure that the dye penetrates all of the individual yarns.

Mama Ango preparing a morinda dye bath.

Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

Above: Mama Fransiska squeezing the morinda paste into her dye bath in 2018

Below: Demonstrating how the bound yarns are pounded in the morinda dye bath. Note the black plastic bag filled with crushed morinda root

A mixture of unbound yarns dyed only with morinda and bound yarns dyed with morinda and previously dyed with indigo. Note the small pieces of loba on the wet yarns

The yarns are left to steep in the dye bath for a few days and are then removed and allowed to dry in the house. They are normally left for two months before they are dyed in a second morinda dye bath. The process is usually repeated six times, the whole cycle taking two years to complete. When finished, these yarns will have been dyed four times in indigo and six times in morinda. Although very few naturally dyed lawo are produced in Nggela today, the majority of those that still are take at least two years to produce because of the length of the morinda dyeing process (de Jong 2013, 269).

To obtain a deeper colour, the yarns can be left to dry for six months, and the process repeated seven more times over a period of four years. Master morinda dyer Mama Fransiska showed us two batches of morinda-dyed bundles at different stages of the dyeing process. The large plastic tub contained yarns that had been processed for one year while the small plastic tub contained yarns that had been processed for three years. She explained that these ikatted warp threads were sufficient to make four lawo redu, four lawo bray, four lawo pundi and four selendangs.

Above: Two plastic tubs filled with morinda-dyed yarns

Below: Mama Fransiska displaying the one-year-old morinda dyed yarns

In the past some weavers went even further, immersing their threads in morinda up to ten times. A few finished them in a hot solution of sappan wood to deepen the red into a distinctive earthy brown. Because morinda dye takes time to bond with the fibres, dyers in Nggela would re-dye their yarns year after year to build up the colour. These yarns were then stored away and were eventually woven many years later.

The finished unbound indigo and morinda dyed yarns

For more information about morinda dyeing in eastern Indonesia, view our morinda webpage.

Return to Top

Other Natural Dyes

The women of Nggela use very few natural dyes other than indigo and morinda.

Mama Ango makes a dark blue by first dyeing her yarns with indigo every day for two weeks. She then washes the yarns in water before dyeing them twice in a bath of mango leaf, kunyit (turmeric) and ash water. The name of the colour and the process is called mbopo.

Mama Ango also makes a green chlorophyll dye using mango leaf, kunyit and kemiri (candlenut).

In the past some dyers have used a hot solution of sappan wood to overdye their morinda to deepen the red into a distinctive earthy brown.

Although tamarind is used to starch the cotton yarns, a process known as reda, it is not used as a dye. As a dye, tamarind colours cotton in a range of shades ranging from soft light brown to reddish-brown and brown, depending on the mordant used (Tepparin, Sae-be, Suesat, Chumrum and Hongmeng 2012; Umar, Najib bn Muh’d nor and Wong 2013). For example on cotton, tamarind alone produces a bright reddish-brown (Tepparin et a 2012).

Nggela weavers also informed us that they never use mangrove as a source of brown dye.

Return to Top

Synthetic Dyes

By the early 1950s villages located close to Ende had already switched to using synthetic dyes (Kennedy 1953, 23). Today dyers in the Lio coastal weaving villages of Wolotopo and Ngalu Polo, and the villages just north of Nggela – Jopu, Wolojita, and Pora – rely exclusively on chemical dyes.

Even in the prestigious village of Nggela, the majority of dyes used today are synthetic. Furthermore, it seems that many Nggela dyers have learnt how to cleverly combine natural and synthetic dyes to mimic the appearance of wholly naturally dyed cloths (de Jong 1994, 214).

Nggela artisans use two types of synthetic dye. The simplest is sumba or kesumbat, which is used by all of the weavers. It is mainly used for dyeing warps red or yellow and for dyeing wefts red or black. It is also often used in combination with morinda as a final colouring following three initial immersions in natural morinda, thus speeding up the process.

In Indonesia various local brands are available, such as Kresno, Nilon, Wantex and Warna Textile, all offering a range of basic colours including green and, in the case of Kresno, light green. Wantex seems to have the widest range with 36 different colour shades. The dyes that these brands offer are not as advanced as those available in the West, and are probably of Chinese origin. Although China produces 33% of the world’s dyestuffs, and contributes 35% of world dyestuff exports, its technology significantly lags behind that of Europe (Japan Chemical Week Nov 2000).

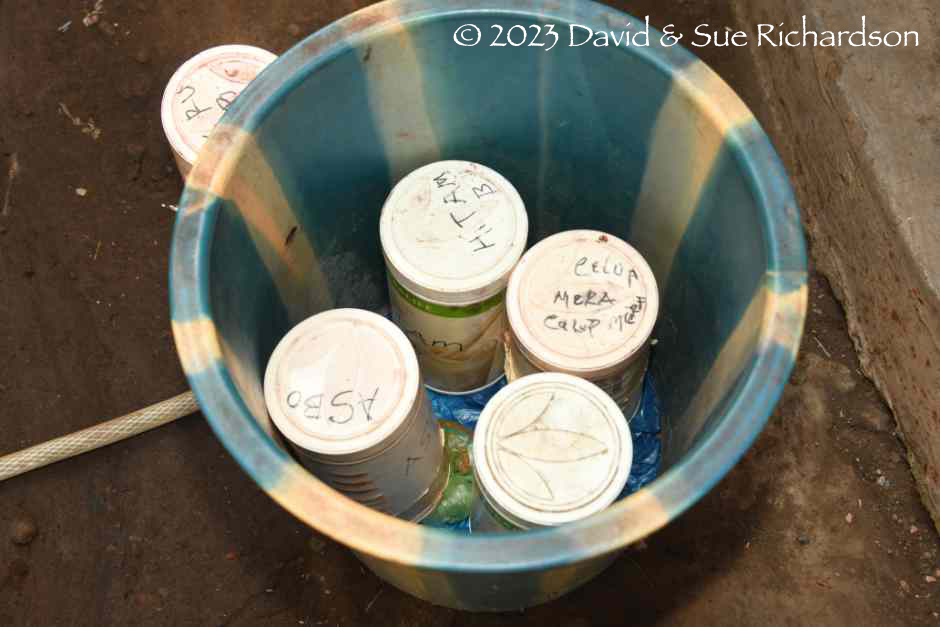

Synthetically dyed yarns drying in Nggela

The second is a better quality but more expensive dye called celup (literally ‘dye’ in Bahasa Indonesia), which consists of two components, soluble naphthol and a diazonium salt. Naphthol dyes are more complicated to use, so only a minority of Nggela dyers know how to use them. They are also hazardous, containing suspected carcinogens. Their application requires two dye baths. The first contains the coupling compound, a naphthol solution prepared with naphthol ASBO, a cream-coloured powder that is soluble in an alkaline solution made by adding caustic soda and salt to water. The second contains the coloured diazonium salt, which can be red, black, blue, green or yellow. The yarns are first steeped in the naphthol bath and after being fully impregnated are then transferred to the diazo bath, where the dye instantaneously forms and binds with the cellulose. The yarns must then be quickly rinsed in cold water.

The women of Nggela purchase their synthetic dyes from a Chinese shop called Toko Jopu in Ende town. They are sold by the kilogramme, with celup merah or celup hitam costing Rp. 350,000 per kg in 2022. They are stored in plastic bags inside white plastic containers.

Celup dyes at Kelompok Kema Sama stored in plastic containers

Some dyers add crushed sirih pinang (betel nut from the Areca palm) to some of their chemical dyes. This is an effective source of tannins.

Return to Top

Unbinding and Starching

Once the dyeing is completed, all of the coconut leaf knots can be cut or untied, a process known as legha.

The dyed skeins of unbound warps can now be immersed in a starch solution and then hung up to dry for two to three days. This process is called reda.

The essential ingredients for the starch solution are tamarind (magé) and candlenut (kemiri), the latter added to strengthen the yarns. Tamarind seeds are first dry fried with no oil, then cooled and de-skinned and then pounded between stones into a powder. This is then added to water and boiled with rice and candlenut.

In the case of the dyed threads for the weft, these too are wound into skeins and dipped into the starch solution before being hung up to dry. Once dry they are placed on a swift and wound into a ball. When required they can be wound onto the stick-like shuttle, known as a lelu poké.

An Nggela lelu poké wound with indigo-dyed yarn

Interestingly in neighbouring Jopu they make their starch solution using tapioca flour, boiled rice, tamarind seed and candlenut. It is called kanji. The starch is pushed into the yarns by hand, because if the yarns are immersed the impurities will stick. This first starching is called aré teba no magé, meaning pushing into the yarns.

Return to Top

Assembling and Focussing

The next stage involves assembling the dyed and starched warps in the correct order so that the ikat pattern can be focussed. To do this the warps are stretched out on an upright bamboo dao frame, which has a fixed end beam attached to an inner moveable beam by loops of rope. The warps wrapped around the moveable beam can be tensioned by twisting the rope loops with a short stick.

Mama Ango with her dyed yarns stretched on a dao frame.

Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

First the ikatted warps must be arranged in bands in the correct sequence with any plain warp stripes inserted between them. It is important to focus the ikat pattern by sliding individual ikatted warps backwards and forwards so that they are in register. The latter is done in three or more sections, starting at one end of the dao frame. Once in position, the warps are locked in alignment by wrapping each warp to a straight stick using a strong thread.

Above and below: Locking the warps in alignment

A fully focused luka sémba on a dao stretching frame

Return to Top

Final Starching

Once the warps have been assembled and focussed, they are starched for a second time, a process called woe. The dao frame is turned upright and the starch applied using a large nggae brush made from the black fibres of the palm tree.

Mama Gina starching the ikatted yarns prior to weaving

Above and below: the nggae palm fibre brush

Starching the locked ikatted yarns next to the house

Some women refer to this second starching process as aré ae magé, meaning smoothing the tamarind onto the yarns.

Return to Top

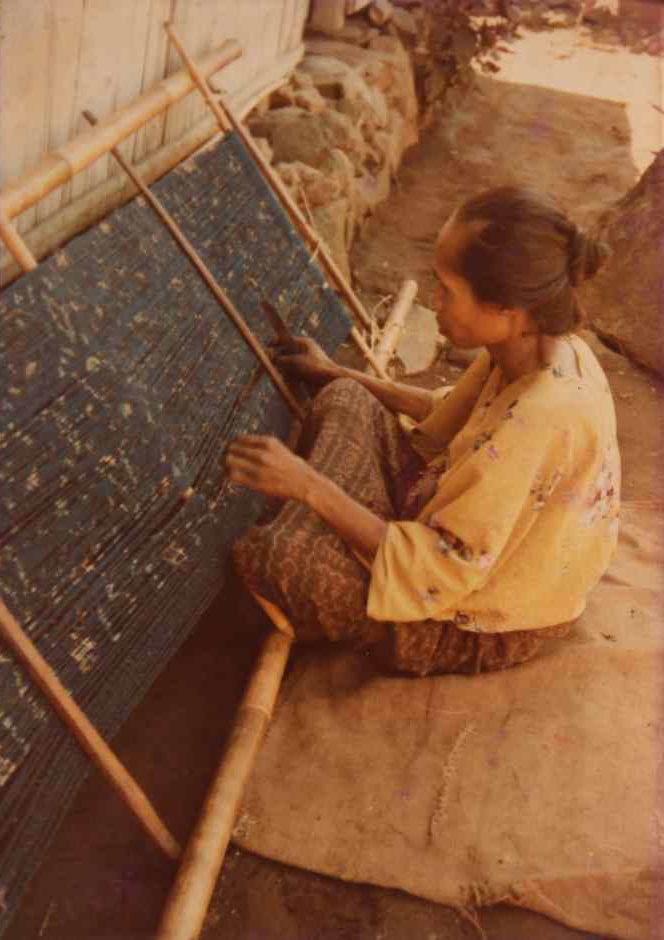

Weaving in Nggela

Once the starched warps have dried, the dao frame is laid on the ground so that the weaver can form the cross by separating the upper warps from the lower warps, and at the same time wind the heddle. This process is called kawé, and the heddle assembly is called the kuku guru.

First the warps are separated into the upper shed and the lower shed by inserting a bamboo pole and progressively arranging alternate warps so they are above and below the pole. Now the heddle stick, known as the wulu, is placed on top of the pole and the heddle, known as the guru, is created by looping a long yarn around the heddle stick and under each lower warp - a laborious task.

Above and below: manually winding the heddle

Mama Ango winding her heddle.

Photographed by Willemijn de Jong in 1988 and reproduced with her kind permission.

The Nggela back-tension loom is similar to those found elsewhere in the Lesser Sunda Islands. Weavers use different ways of supporting the warp beam, such as raising it on stones and placing it behind ground stakes or tying it to the side of the house.

Mama Ri weaving a synthetically dyed lawo pundi below the floor of the house

Weaving a luka sémba

Weaving activity in Nggela is intense. De Jong estimated that the average annual output of cloths per household was around fifteen pieces in 1990 (2013, 276). This suggests that total village output was around 4,500 cloths per annum, some produced for wearing but many made for gift-giving and selling.

Mama Ango’s loom at her former home in Nggela before it was destroyed by fire in 2018.

Mama Ango likes to weave sitting on a small stool. Note the carved wooden yoke

Teresia Korse weaving in the shade below the house

Loom Terminology

| To weave. weaving | seda |

| Loom | ala |

| Upright breast beam posts | kuku toka |

| Breast beam with a clamp | kogo |

| Warp beam | lani kolo |

| Yoke | kabhé |

| Yoke rope | ajé kabhé |

| Sword | ngewi |

| Temple/stretcher | tubo |

| Heddle yarns | guru |

| Heddle stick | kuku téki or wulu |

| Whole heddle | kuku guru |

| Bamboo shed roll | bella |

| Lease sticks | pepa tué |

| Foot rest | setu ghai |

| Shuttle | lelu poké |

Return to Top

Sewing Up the Sarong

The sewing-up process is called rei. Each panel is removed from the loom and the unwoven section of warps is removed. The three panels of the lawo are neatly joined together and are then folded in half to form the tube skirt. The sides of the panels are then joined using a rolled seam.

Return to Top

The Complete Weaving Process

The whole process for making a woman’s sarong with chemical dyes takes up to 30 working days, working 8 hours a day. However, with natural dyes it takes at least two years (de Jong 2015: 164-193). Mama Fransiska told us that it takes her at least three years to produce a masterpiece. In 2023 she showed us one of a pair of lawo redu that she had taken fourteen years to complete, because of the time required to achieve the intense morinda colours. The other matching lawo had been worn by President Jokowi’s wife, Iriana Joko Widodo, when she visited Ende with her husband on 1 June 2022.

In the 1960s, before the arrival of chemical dyes and at a time when yarn was still partly hand-spun, weavers made only a few pieces of cloth per year. As already mentioned, in the 1990s, a weaver could produce about 15 synthetically dyed pieces with commercial cotton a year – 6 women’s sarongs, 2 men’s sarongs, about 5 shoulder cloths and some small scarfs.

Synthetically dyed sarongs are preferred by the weavers not only because they are easier and faster to make, but also because the ikat patterns are clearer, the texture is smoother and they are more comfortable to wear (de Jong 2020, 2). However, naturally dyed sarongs are still made because tourists and special dealers prefer them and they are more profitable.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 21 February 2024.