Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

West and East Bengal

Traditional Kantha Making

Kantha Embroidery Stitches

Types of Kantha

Par Tola and Nakshi Kantha

The Demise and Rebirth of Kantha

The Gurusaday Dutt Museum Collection

The Calico Museum Collection

The Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

The Philadelphia Museum of Art Collection

The Mingel International Museum Collection

The Richardson Collection

Bibliography

Introduction

The ancient Bengali domestic craft of kantha emerged as a way of recycling items of old cotton clothing such as saris, lungis and dhotis into embroidered quilts, commonly known as kanthas. It was the folk art of the poor. Indeed, the name kantha comes from the Sanskrit term kontha, meaning rags. However in East Bengal dialects kantha is also referred to as kheta or kentha, while in Bihar and parts of West Bengal, the kantha is also known as a sujni.

A nineteenth century kantha quilt in the collection of the The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (199 by 142cm)

It is likely that the art of kantha dates back to antiquity. However the earliest mention of the craft was around 1557. In his book Sri Chaitanya Charitamrita, the Bengali poet Krishnadasa Kaviraj mentions how the guru Chaitanya, while teaching in the holy city of Puri, received a home-made kantha from his mother, brought to him by some visiting pilgrims.

The most important forms of kantha were made by women for use in their own homes such as bed quilts or coverings, coverlets, seating mats, pillow covers and all-purpose wrappers. A traditional full-sized kantha was roughly six feet long (183cm) and five feet wide (152cm) and was used by the poor as a protective layer for sleeping in the winter (Zaman, 2012).

Geographically, kantha was predominantly practiced amongst rural women in the previously undivided Indian state of Bengal as well as in parts of Bihar and Orissa.Return to Top

West and East Bengal

The independent Sultanate of Bengal was the dominant power in the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta throughout most of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. After being overwhelmed by the Mughals, Bengali Subah or Mughal Bengal became the largest polity within the Mughal Empire, finally emerging in the eighteenth century as independent Mughal Bengal ruled by the Nawabs of Bengal. It was composed of present day West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and Bangladesh.

After Robert Clive’s victory over the Nawab of Bengal in 1757 and the defeat of the combined forces of the Nawab of Bengal, the Nawab of Awadh and the Mughal Emperor in 1764, the British East India Company took control of the Bengal Presidency (Province) in 1765.

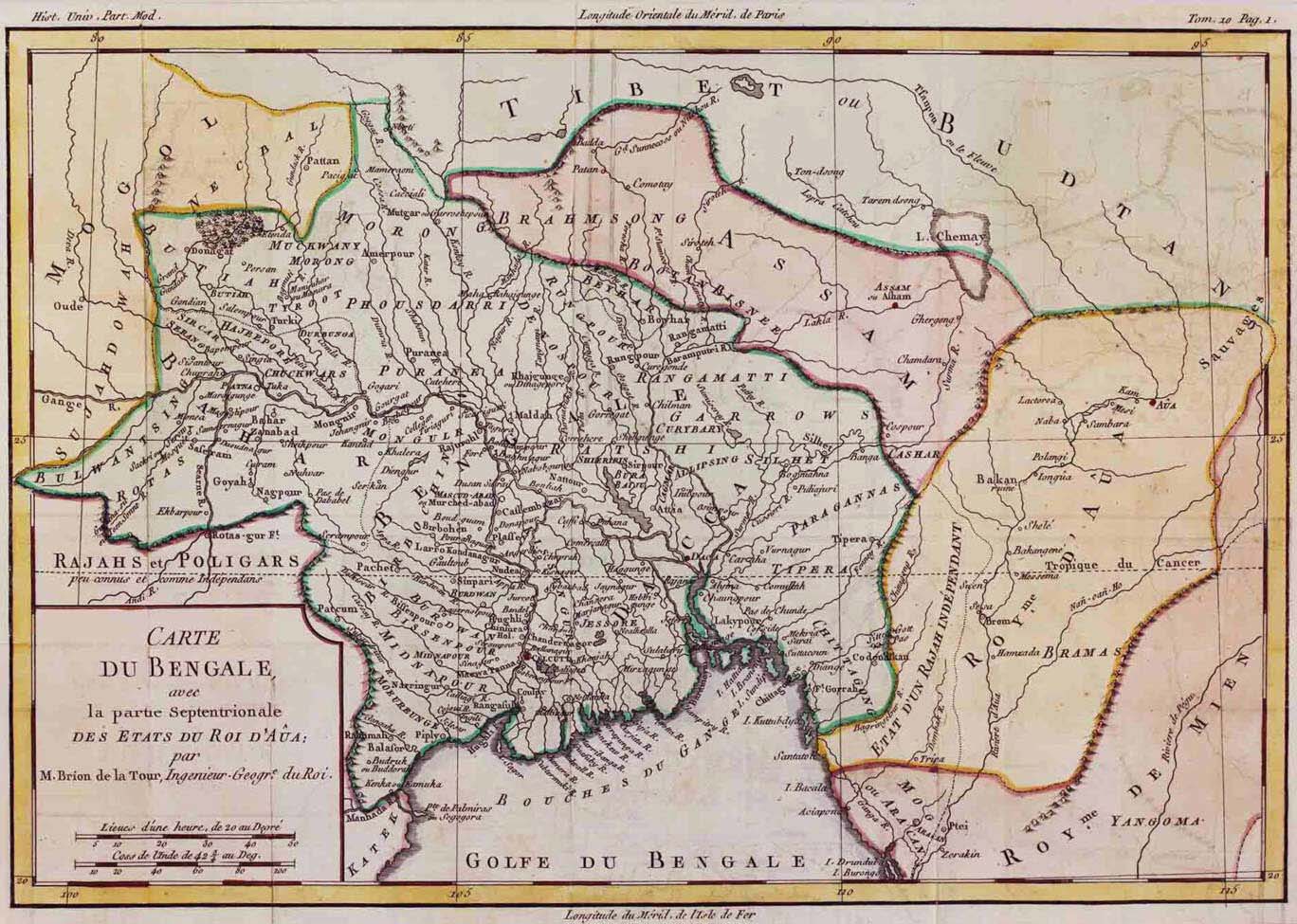

Carte Du Bengale, dated 1785. Although attributed to Arkstée and Merkus it is actually based on a map by French geographer Loui Brion de la Tour

In the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858 stripped the East India Company of all its administrative powers. Its Indian possessions and armed forces were taken over by the British Crown, the rule of India passing from the directors of the Company to a Secretary of State for India advised by a council whose members were appointed by the Crown. The Crown also directly appointed the Governor-General or Viceroy of India and the provincial governors. It was the start of the British Raj, the direct imperial rule of India by Great Britain.

With its capital of Calcutta strategically located on the Hooghly River, the eastern outlet of the mighty Ganges River, Bengal soon became the political and economic cente of the British Raj. At that time the Presidency of Bengal still included Bihar and Orissa.

In 1905 in an attempt to accommodate long standing Muslim grievances, the British Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, partitioned Bengal along religious lines – dividing it into the provinces of Assam, West Bengal and East Bengal, the latter with its capital at Dhaka. This move caused consternation among Bengali Hindus and led to huge demonstrations, with the terrorist Swadeshi movement targeting British colonial officers and prominent Muslims. Leading Muslims responded in 1906 by forming the All-India Muslim League, committed to the creation of a homeland for the Muslims of India.

The partition of Bengal was short-lived. During the royal visit to Delhi in December 1911, King George announced both the annulment of the division of Bengal and the relocation of the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi. The following year Bihar and Orissa were separated from Bengal to become a single separate state.

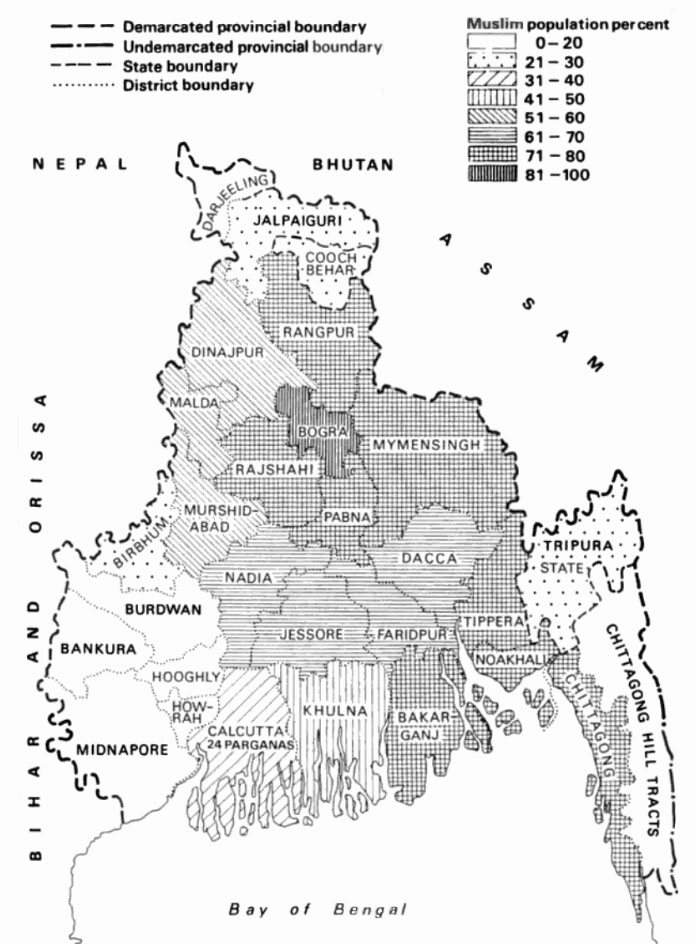

The demographic situation in Bengal was particularly complex. In 1931 the province had a population of 49 million, 56% of who were Muslims, mostly concentrated in the eastern regions, while 44% were Hindu (Hill 12).

Distribution of the Muslim population of Bengal from the 1931 census

Muslims per 100 of the total population

Map of Undivided Bengal with Sikkim from the Imperial Gazetteer of India, The Edinburgh Geographical Institute, 1931. Published by John Bartholomew and Son Ltd.

Nationalist pressure increased during the 1930s under the leadership of Gandhi who demanded full independence from British rule. The British partially responded in 1935 by granting autonomy to the separate Indian provinces, virtually isolating them from imperial authority. Although Indian support proved to be essential to the British cause during the Second World War, the independence movement was strengthened enormously whilst the world standing and economy of Britain was greatly weakened. The mainly Hindu Indian National Congress fiercely opposed the war although the Muslim League supported it. The Bengal famine of 1943, in which many rural Bengalis died of malnutrition despite no significant domestic food shortage, further antagonised local opinion.

Following the defeat of Winston Churchill in the July 1945 general election, the new Labour government led by Clement Attlee came into power determined to grant India independence. Yet despite repeated talks, the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League could not agree on the form of the new state. In March 1946 Attlee announced that the British were committed to the transfer of power but did not set a date for it to happen.

After another failed conference in 1946, the Muslim League asserted its demands for a separate Muslim state and called for general strike on 16 August, terming it the Direct Action Day. This resulted in the worst communal riots that British India had ever experienced. In Calcutta rioting between Hindus and Muslims resulted in thousands of deaths and six British battalions had to be deployed to restore order. The violence quickly spread to Bombay, Delhi and the Punjab.

Police using tear gas to disperse rioters in the streets of Calcutta on 24 August 1946

On the 10 February 1947 Atlee promised that independence would be granted by June the following year. One month later the naval commander Viscount Louis Mountbatten was appointed Viceroy of India and given a mandate to oversee the British withdrawal. Yet despite having established good relations with leading Hindu politicians he was unable to persuade the leader of the Muslim League to support an independent united India. Frustrated with the complexity of Indian politics, Mountbatten realised that this goal was unattainable and hastened the British withdrawal. On 3 June 1947 he announced the partitioning of British India into India and Pakistan. The Indian Independence Act was passed in the House of Commons on 18 July, the creation of the separate Dominions of India and Pakistan scheduled for midnight on 14 August. Violent clashes between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims soon followed.

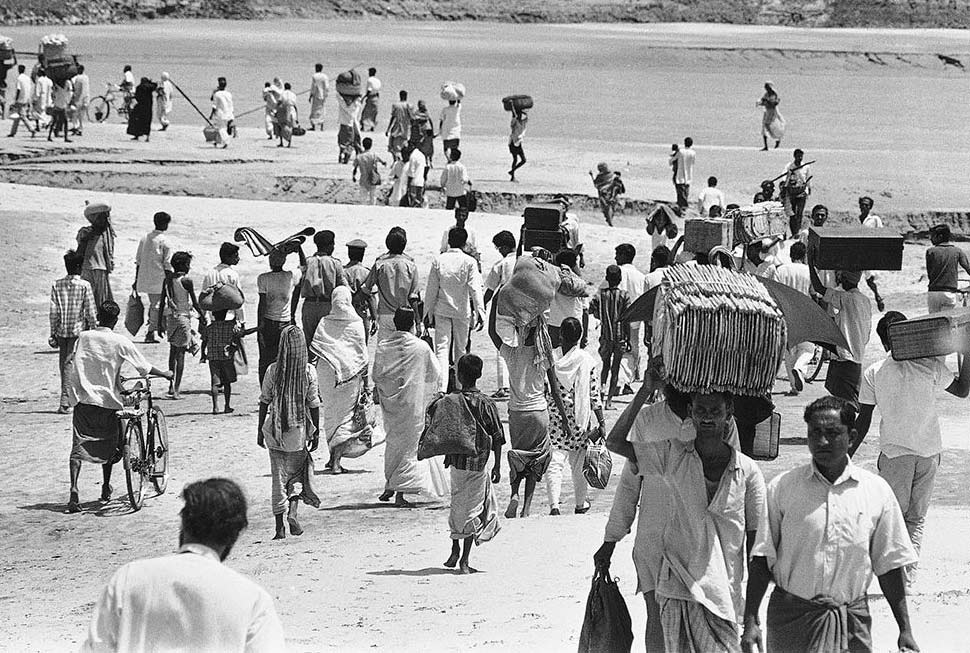

This second partitioning of Bengal resulted in East Bengal becoming a province of Pakistan while West Bengal remained within India. Masses of Hindus, most of them in business and teaching, left East Bengal, crowding Calcutta and places as far away as Delhi. Muslims living in West Bengal, lured by promises of a golden future as citizens of a Muslim Pakistan, migrated to East Bengal. The whole sub-continent experienced one of the largest mass migrations ever recorded in modern history, with a total of 12 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims moving between the newly created nations of India and Pakistan.

In East Bengal, many of the newly arrived migrants soon realised that they had traded domination by the British for domination by West Pakistan. In 1948 the West Pakistan government ordained that Urdu should become the sole national language, sparking extensive protests throughout East Bengal. To supress opposition, public meetings and rallies were banned. When police killed student demonstrators in 1952 there was widespread unrest.

In 1955 the four western provinces of Pakistan were merged into a single unit called West Pakistan while East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan. The following year Pakistan ended its dominion status and proclaimed itself an Islamic republic. The Bengali language was finally granted official status that year.

The tense relations between East and West Pakistan finally reached a climax in 1970 when the Awami League, the largest political party in East Pakistan, won a landslide victory in the national Pakistan elections, taking the majority of seats. Their six-point programme envisaged an autonomous East Pakistan within a federal parliamentary republic. The Pakistani military junta procrastinated, delaying the inaugural session of the National Assembly, and the Awami League responded with a programme of non-cooperation.

Unwilling to transfer federal powers, the Pakistani junta began planning a military crackdown. On the night of 25 March 1971, they launched Operation Searchlight in Dacca with the aim of systematically eliminating nationalist Bengali civilians, students, intellectuals, religious minorities and military opponents. The Awami League responded by declaring independence the following day.

By mid-May Pakistani forces had gained control of the towns, but large-scale civil disobedience continued as did the systematic killing. The exact figures are unknown, but hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of Bengalis were killed and hundreds of thousands of Bengali women were raped, leading to widespread international outrage. Some 10 million Bengali refugees flooded into India from the east.

Refugees crossing the River Ganges at Kushtia in 1971, fleeing the violence in East Pakistan

The Indian government responded by organising, training and arming the East Bengali separatists, resulting in the Pakistan Air Force launching a pre-emptive strike on Indian Air Force bases across north-western India on 3 December 1971. After formal declarations of war, the Indian army responded with a ferocious land and air assault against the Pakistani occupation forces. The outcome was swift and decisive, with the Pakistani army surrendering on 16 December 1971.

Lieutenant-General Abdullah Niazi (right), chief of Pakistan’s Eastern Command, signs the surrender document besides Lieutenant-General Jagjit Aurora (left), chief of India’s Eastern Command in Dacca, Bangladesh, on 16 December 1971

After gaining its independence in 1971, East Pakistan became the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, the name Bangladesh literally meaning the ‘Land of the Bangla or Bengalis’, the term Bangla being seen as endemic whereas Bengali was associated with British India.

Today Bengali is the world’s fifth largest language, spoken by over 260 million people.Return to Top

Traditional Kantha Making

To produce a kantha quilt, a base fabric was made from layers of old cloth, traditionally between five and seven, and this was embroidered using the yarns recovered from the borders of old saris, lungis and dhotis. More recently, modern kanthas are often made with new materials and those made with much coarser cotton can suffice with only two layers. Once the main embroidery decoration is completed, the layers making up the kantha are quilted.

The process began by preparing the separate layers so that they all had the same dimensions. If some cloths were too small they were stitched together, sometimes almost invisibly, to obtain the required width. Several women would work together to spread the layers of cloth on the ground, making sure there were no folds or creases. Traditional kanthas tend to be somewhat uneven in shape because they were not stretched in a frame. The layers were held flat on the ground, either weighted on each corner or fastened together with needles or thorns, while the edges were folded in and stitched. Then two or three rows of large stitches were made down the length of the layered cloths to hold them together and to provide a frame for the later placement of motifs. At this stage the layers could be folded and put away so that they could be worked on at a later date.

A nineteenth century kantha coverlet in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (198 by 144cm)

In the past kantha makers did not draw motifs onto the cloth but outlined them with stiches. The main focal points, such as the central motifs, were embroidered first, followed by the corner motifs and then the filling motifs.

Whilst quilting is found across many different cultures, kanthas are made by embroidering the layers of cloth together, not stitching, patching or appliqueing them. Once the embroidery decoration is outlined, and in some cases even completed, the kantha-maker fills the empty spaces with kantha running stitch, known locally as kantha phor.

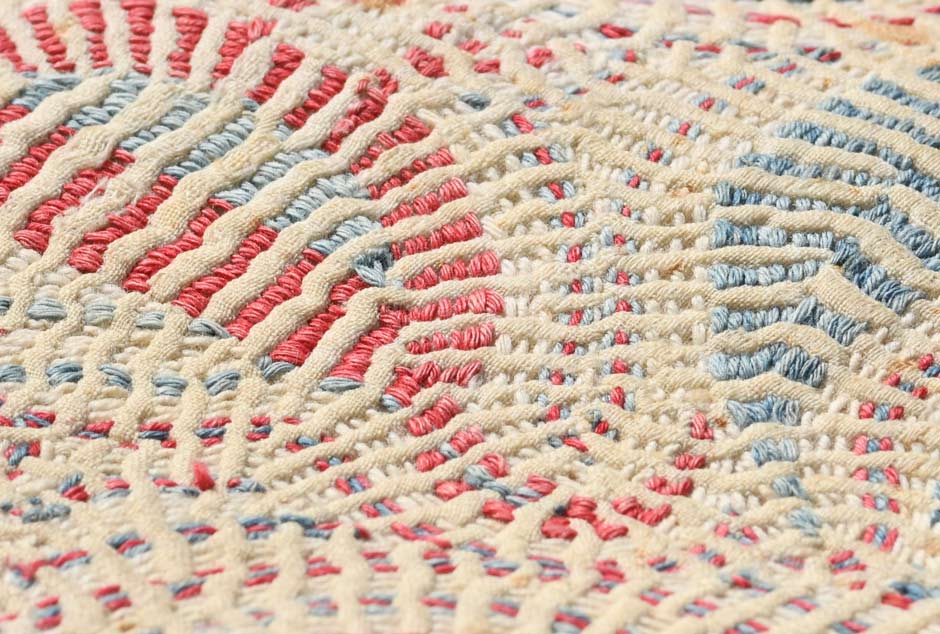

In traditional kanthas, the running background stitch is positioned around the motifs, moving out in parallel lines and eventually merging with the running stitches surrounding the other motifs. This is sometimes called echo quilting. The parallel lines of stitching are sewn through all of the layers of cloth, the spaces between the stitches being larger than the stitches themselves. When the next row is sewn parallel to the previous row, the stitches are positioned slightly behind or slightly forward those in the preceding or succeeding rows. This produces a rippled effect, forming wavy ridges between the stitches. However if the kantha maker does not pierce through all the layers of material, the rippling effect is lost. These ripples have the effect of making the motifs stand out in relief from the background.

Above and below: Ripples formed by rows of kantha running stitch

Kantha Embroidery Stitches

In the past, kanthas were made almost exclusively using simple running stitch, sometimes applied in ingenious ways. According to the collector Stella Kramrisch, the finest old kanthas were decorated using a variety of effects obtained through the dexterous manipulation of simple running stitch. Some of the variants of this stitch have been given their own identity.

Today there are many different types of embroidery stitch or phor employed in kantha making. In Bengali the term phor not only means a sewing stitch but also describes a weeding hook.

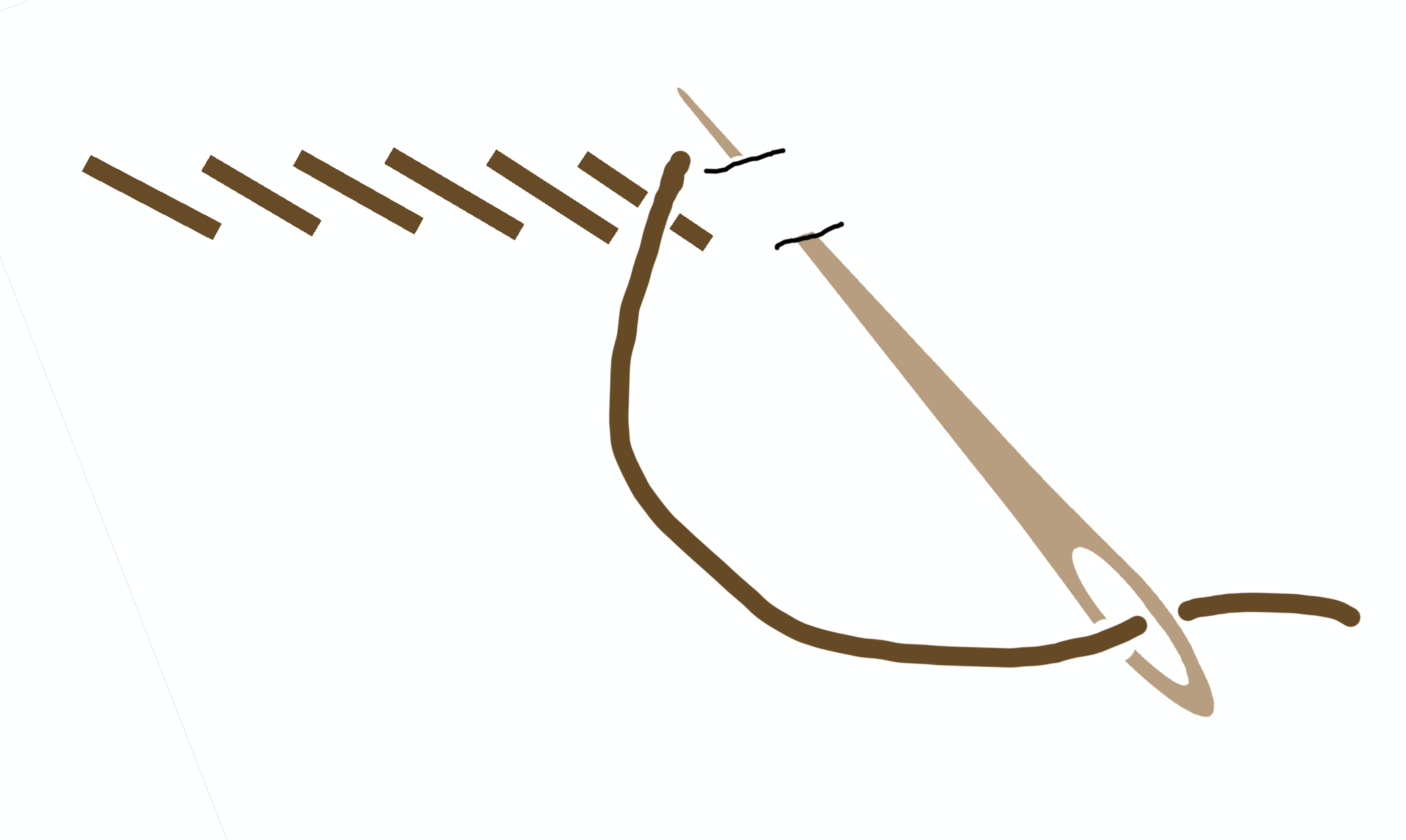

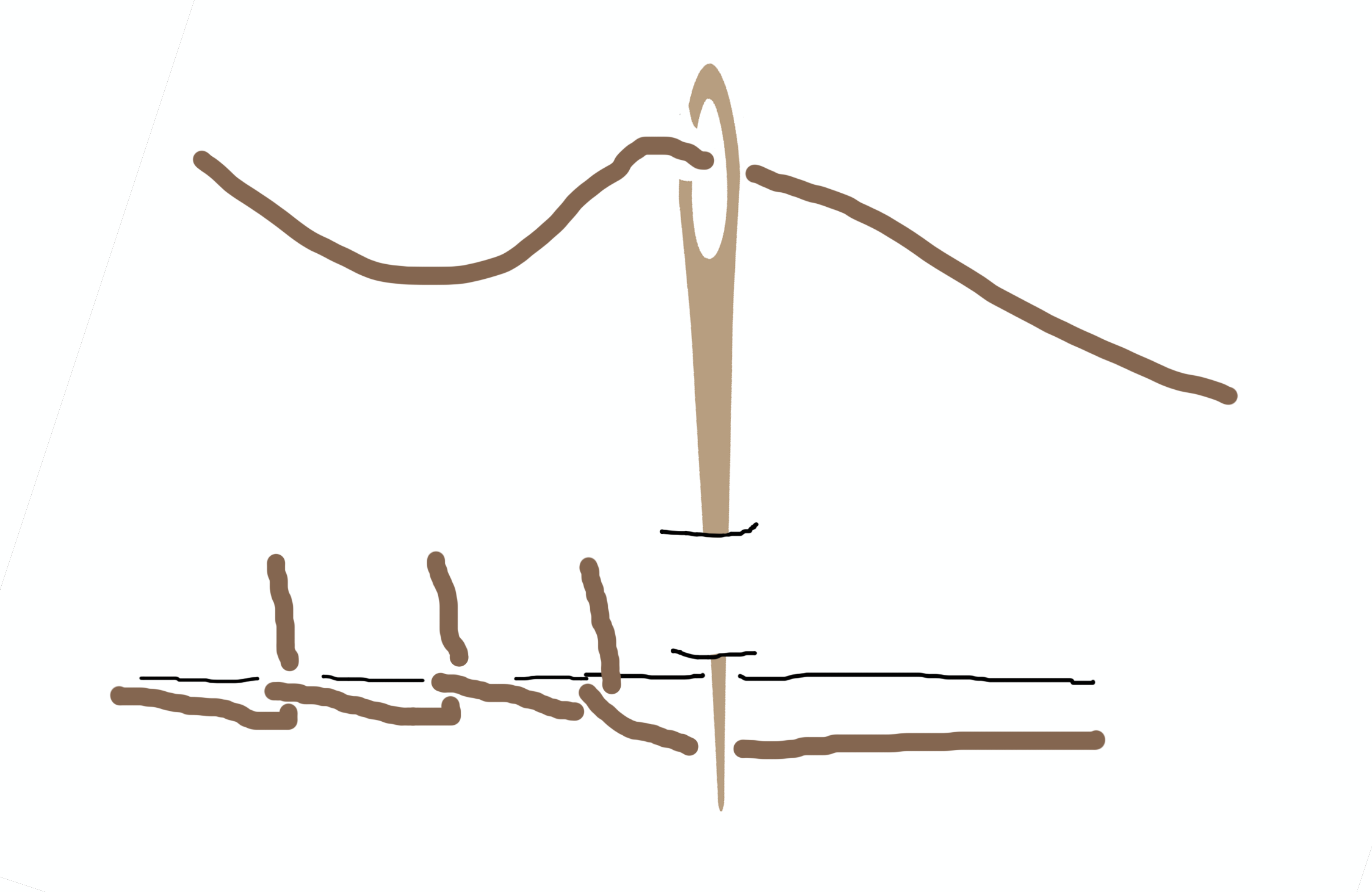

Kantha or Kucki Phor – Running Stitch

Kantha phor is a linear quilting stitch sewn in a horizontal direction relative to the surface of the kantha. Several stitches are sewn before the thread is pulled through the layers of materials making up the kantha. The rows of stitches are slightly staggered to create the characteristic rippling effect.

Kantha phor running stitch

Chatai or Pati Phor – Mat Stitch

The terms chatai and pati relate to types of woven grass mat, since this type of kantha stitch has a similar resemblance. It is sometimes mistakenly confused with satin stitch.

In chatai phor, parallel running stitches are placed closely together to give the appearance of satin stitch. However the areas covered by stitching are bare on the reverse, whereas in satin stitch they are not. To embroider a flower in chatai phor, the stitching proceeds in a circular manner with each part of every petal stitched in rotation, whereas in satin stitch the petals are embroidered one at a time.

Roundel embroidered in chatai phor

Kaitya Phor – Bending Stitch

In kaitya phor or kushtia phor, parallel running stitches are once again placed closely together to give the appearance of satin stitch. However each line of stitches is positioned slightly ahead or behind the previous row to create a staggered or swirling effect.

A swirled roundel embroidered in kaitya phor

Lik or Anarasi Phor – Holbein Stitch

Lik phor is a spaced running stitch applied in parallel rows, the spaces between the stitches being equal and the spaces between the rows being equal. It is sometimes called ghar hashia or double running stitch. In some work the rows alternate so each stitch is flanked by a space and vice versa.

After completing a row of evenly spaced running stitch, the spaces left can be filled with running stitches sewn in the opposite direction. A contrasting coloured thread can be used for the second row of stitches.

Lik phor

Lohori or Beki Phor

Lohori phor is another running stitch applied to create angular designs. It is sewn with thick yarns to create swirling patterns or wavelike designs.

Lohori phor filling stitch

Bhorat Phor – Kashmiri Stitch

Bhorat phor consists of a long stitch held down in the middle by a short one, somewhat similar to couching. It is used to embroider large areas with a solid block of colour. It is similar to the stitching used in Kashmiri shawls.

Bakhiya Phor – Back Stitch

Bakhiya phor or back stitch is used for outlining figures or shapes. It follows complicated designs well and has a continuous appearance because there are no spaces between each of the stitches.

Each stitch is sewn one stitch length backward on the front side and two stitch lengths forward on the reverse side to form a solid line of stitching on both sides of the fabric.

Dal Phor – Stem Stitch

Dal phor or stem is also sometimes used for outlining motifs. It is quick and easy to work, appearing as a row of oblique evenly sized stitches. The needle is pushed up through the cloth and moved forward the length of one stitch and then moved back down to sew the adjacent parallel stitch.

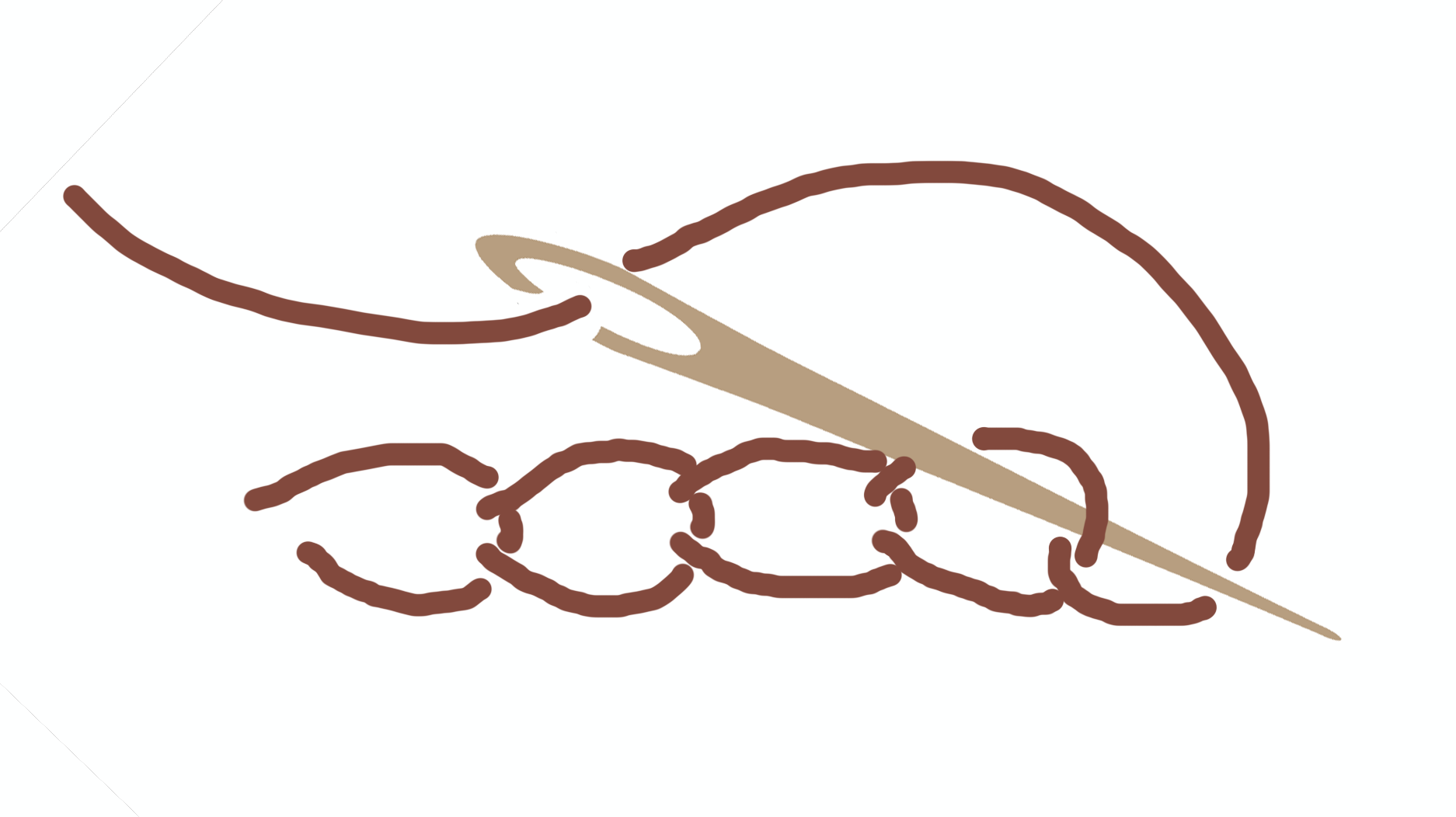

Chain-Stitch

Chain stitch is a loop stitch in which the yarn is passed over the point of the needle as it emerges from the bottom of the cloth. This forms a loop, which is secured by the following stitch.

In the example below, the blocks of lohori phor filling stitch have been outlined in chain stitch using a thin doubled thread.

Blanket Stitch

Blanket stitch is sometimes used to neatly finish edges.

Cross-Stitch

Although one of the oldest known embroidery stitches, cross-stitch was not traditionally used for kantha work and seems to be the most recent addition to the kantha stitch repertoire. A variation of cross-stitch, called Gujrati stitch, is being increasingly used to decorate modern kantha saris.

Herringbone-Stitch

Herringbone stitch is not common but is occasionally used to decorate borders.

Return to Top

Types of Kantha

Traditionally, kanthas were practical household items, made over a long period of time for use by the entire family. Consequently every family in Bengal had a number of kanthas for their personal use. As a result there were many different forms.

The majority of kantha was used as light coverlets during the mild Bengali winters and breezy monsoon nights. However another important use was for swaddling babies. Expectant mothers would spend the last months of their pregnancy stitching the cloth, in the belief that it would bring good fortune to their families and protect the baby from diseases. Other kanthas were specifically created in different sizes for use as floor covers for special guests, as prayer mats or pillow covers, satchels or purses, to store personal items or to cover the Quran.

The most common types of kantha are listed below:

- Lep kantha are large rectangular wraps, about 6 feet by 4½ feet, heavily padded to provide a warm coverlet for the winter.

- Sujni or sujani kanthas are rectangular cloths used as blankets or ceremonial spreads for seating honoured guest at an event such as a wedding, engagement or birthday, or for welcoming a member of the older generation. Unlike other kanthas, the designs on sujni kanthas were often stamped using wooden pattern blocks.

- Bayton or baiton kanthas are square and about 36 inches wide, used to wrap books, clothes and other valuable items. They have elaborately decorated borders and when used as book covers are often embroidered with swans. They are also donated as gifts. They are sometimes referred to as bostani or bastani kanthas.

- Ashon kanthas are a sitting mat for a bride at her wedding.

- Ooar kantha are rectangular pillow covers. They have simple designs with a decorative border sewn around the edges.

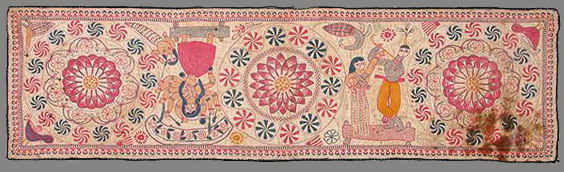

- Arshilata kanthas are narrow rectangular covers used to roll away and store small household objects such as combs, mirrors, kajal eye liner, cosmetic vermillion sindoor, sandal paste and other toiletry items.

- Durjani or durfani kanthas are small squares with an elaborated border made to protect a wallet. The three corners of the square are folded together and sewn to form an envelop-shaped small bag, while the fourth is folded over to form a covering flap. A string is fastened to the point of the flap, which can be wound around the closed bag to make it secure.

- Batua or gilaf kanthas were made in the same way as durjani kanthas but are used as a case to hold a Quran.

- Rumal kantha are small handkerchief sized squares about 12 inches wide used as plate coverings or absorbent wipes.

A selection of arshilata kanthas on display in the Gurusaday Museum, Kolkata

Note that sujni is a term of Persian origin derived from suzan (needle). On a strict technical basis is applied to a type of embroidery that is similar to but differs from a normal kantha as a result of a different stitching technique. In a sujni kantha the running stitch is added in straight lines not in the form of spirals, circles or conical forms, and the motifs are outlined in a dark coloured chain stitch not running stitch. In Bengal, sujni kantha are mainly found in the Rajshahi area of Bangladesh. The same technique is also practiced in Bihar.

However in everyday use, the term sujni kantha is applied in Bengal to all large richly decorated covers or seating mats that are either ceremonial or are not intended for daily use.

Return to Top

Par Tola and Nakshi Kantha

Many textile scholars divide running stitch kanthas into two types:

- par tola kanthas with geometric patterns that can be simple or complex. Here no pattern is drawn and the stitching count is done from memory.

- nakshi kantha with figurative patterns, such as animals, birds or humans, or scenes of daily life. Here the pattern was traditionally outlined with needle and thread. In some, such as sujni, wooden blocks were used to print the outline. Today, patterns are first drawn by pencil on tracing paper and then copied onto the fabric.

The Bengali term par means pattern while nakshi derives from naksha, meaning design from the Persian naqsa.

The earliest surviving kanthas have restrained colour palettes resulting from the use of indigo- and madder-dyed yarns. Central lotus medallions were surrounded by floral motifs and conical forms arranged in concentric spirals. Many echoed local alponas, the auspicious motifs drawn in white rice paste by Bengali women on the sides of their houses during important festivals such as Durga Puja. Over time more elaborate patterns developed, which became known as nakshi kantha, illustrating the lives of the women that made them, their natural surroundings and their religion and culture.

The addition of the descriptor nakshi to the word kantha may date back to the seventeenth century. However the term nakshi kantha gained considerable traction following the publication in 1929 of the narrative poem Nakshi Kanthar Maath (Field of the Embroidered Quilt) by Jasimuddin Mollah, a Bengali folk poet from Faridpur in East Bengal. This tragic love story about a young kantha maker was translated into English ten years later by E. Mary Milford.

From our perspective, the distinction between these two kantha types is of little value. The simple term kantha is sufficient to define them all.

Return to Top

The Demise and Rebirth of Kantha

Kantha making declined in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century due to a combination of factors. By the 1930s it was hard to find examples of kantha in Bengal other than in museum and private collections.

One important cause was the ready availability of cheap machine-made textiles from Europe. In the past Bengal had been a major producer of hand-woven cotton textiles, many of which were imported into Britain in the second half of the seventeenth century by the East India Company. This severely reduced demand for British woollen and linen textiles, causing consternation among weavers, spinners, dyers, shepherds and farmers. The British parliament responded by passing the Calico Acts of 1700 and 1721, which banned the import of most cotton textiles, the 1721 act even prohibited the sale of most cotton fabrics, whether imported or domestic. These acts were repealed in 1774 and replaced with 70 to 80% tariffs on Indian exports to Britain.

After beginning to ship machine-made yarn and cotton cloth to India in the 1780s, British exports grew rapidly and by 1832, Bengal-based R. M. Marin wrote:

By increase of export of cotton goods to India from Britain many millions of Indo-British subjects have been totally ruined (Riello and Parthasarathi 2009, 400).

By the late nineteenth century the decline in Indian cotton manufacturing had become a central aspect of the criticism of British rule by Indian nationalists (Riello and Parthasarathi 2009, 401). As cheap imported textiles became widespread, even the tradition of kantha making was undermined.

A second reason for the decline in kantha embroidery was increasing poverty. This forced many women to seek paid employment, limiting the time previously available for stitching kanthas (Chen 1984, 50).

Although several initial attempts were made to promote kantha they were not long lasting. In the 1910s Sarojnalini Devi, the wife of the civil service officer Gurusaday Dutt, became immersed in rural village life and culture, bringing many of its aspects to the attention of her husband. Following her death in the early 1920s, Gurusaday Dutt continued popularising Bengali folk culture, including kantha, later establishing his Bratachari movement aimed at strengthening cultural awareness across India irrespective of sex, religion or caste (see The Gurusaday Museum Collection below).

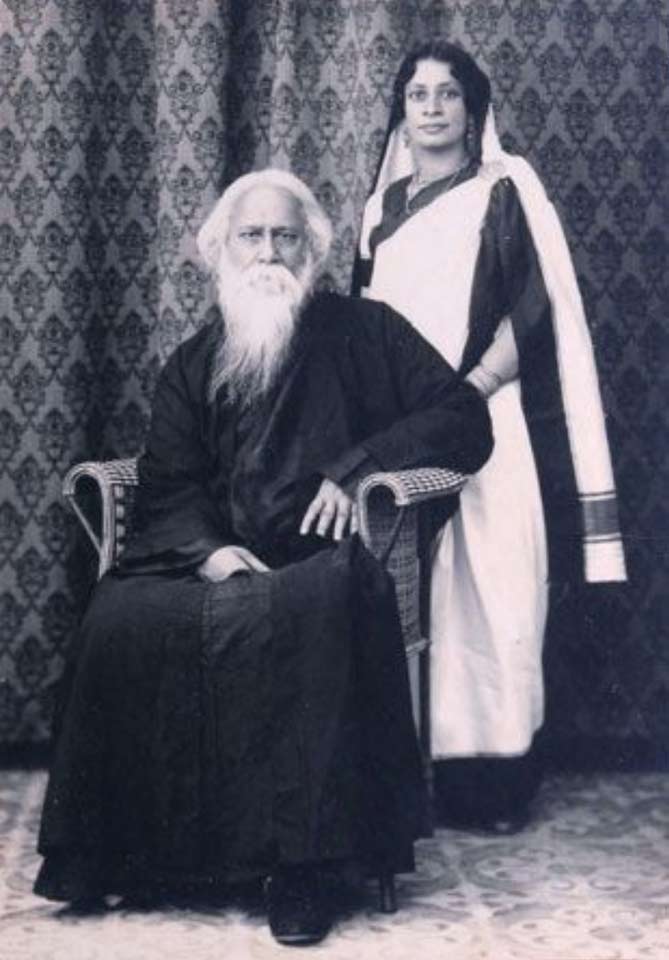

During the 1940s Pratima Devi led an asserted attempt to revive kantha. She had been born in Calcutta and was married to the son of Rabindranath Tagore, the famous Bengali Nobel laureate poet who was a champion of Bengali art and culture. Assisted by Srilata Sarkar, a talented art student, she spearheaded a rural reconstruction project at the Kala Bhavan (Institute of Fine Arts), the fine arts faculty at Vishwa Bharati University in Shantiniketan, which had been founded by her father-in-law.

Pratima Devi with her father-in-law Rabindranath Tagore

Sadly her efforts were disrupted by the declaration of Indian independence on 15 August 1947 and the subsequent traumatic partition of the country, which tore Bengal apart. This resulted in many Hindu families fleeing from East Bengal, taking their kantha making skills with them. By 1954 the Calcutta-based folk art researcher Tofail Ahmed was referring to kantha as a lost art.

It was only after the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence that kantha was fully revived, although not in its original form. Many women in Bangladesh were widowed or impoverished by the war, while others migrated with their families into West Bengal. After independence there were attempts to provide work for such women by drawing upon their traditional needlework skills. Districts with a strong kantha tradition such as Jessore, Kushtia, Faridpur and Rajshahi established cottage industries and attempted to market kanthas as commercial products although many were not initially successful.

In early 1972 a new NGO, the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), was established with the objective of providing a degree of relief and rehabilitation, focusing on schemes to increase the income of rural women. Even so, it was not until 1979 that BRAC recognized the opportunity to promote kantha as a means of helping families, thanks to a chance discussion with a group of women in a village in Jamalpur district. BRAC field workers asked the villagers if they still possessed the quilts that their mothers had made and if so, whether they could reproduce them (Chen 1984, 51). After confirming that they could sew simple kanthas, BRAC placed a formal order for 24 pieces. The trial was a success and an increasing number of women became involved.

As production increased, BRAC employed designers to create patterns that could be pre-printed onto cotton cloth for the kantha makers and embroiderers were encouraged to use a hoop to sew their motifs. The number of kantha products became increasingly diversified and included cushion covers, bedspreads, wall hangings and children’s clothing. Although the art of kantha making had been revived, it had been transformed into a commercial enterprise with little resemblance to its earlier naïve domestic roots.

Meanwhile on the Indian side of the border, the Department of Micro Small & Medium Enterprises and Textiles of the Government of West Bengal established two bodies to support and promote local handicraft producers, including kantha artisans. These were the West Bengal State Handicrafts Cooperative, known as Bangasree, founded in 1957 and the West Bengal Handicrafts Corporation, more popularly known as Manjusha, set up in 1976 (Bajpai 2021, 41).

Later in the mid-1980s Shamlu Dudeja, a teacher and social worker, became inspired by an exhibition of kantha in Calcutta and set up the SHE Foundation (Self Help Enterprise), encouraging Bengali embroiderers to diversify into silk kantha saris. With the help of her daughter Malika Varma, she began to promote the silk kantha saris to the urban elite of Calcutta, later establishing the trading company Malika’s Kantha Collection in Alipore in 1993. Kantha had finally been transformed from the folk art of the rural poor to the haute couture of the urban elite.

Return to Top

The Gurusaday Dutt Museum Collection

The Gurusaday Museum on Diamond Harbour Road at Joka, some nine miles south of Kolkata, houses the amazing kantha collection of Gurusaday Dutt, a former Indian civil servant. His kantha collection is very special because the contents were collected directly by Dutt in the field and not simply purchased through dealers or auctions.

Gurusaday Dutt

Dutt was born in 1882 into a family of modest means in the village of Birasree near Sylhet in East Bengal. Despite being orphaned at a young age – his father died when he was 9 and his mother when he was 14 – he went on to study at Calcutta University and later, thanks to a scholarship, at Emanuel College, Cambridge. He joined the Indian Civil Service in 1905 and over the next 25 years travelled to many remote parts of rural Bengal, becoming seriously interested in its folk culture. He gained further inspiration in 1929 during a visit to London where he attended a folkdance recital at the Royal Albert Hall. After returning home he began collecting and cataloguing examples of Bengal folk art, including kanthas and other items of everyday use.

Dutt was a committed nationalist and in 1932 he established the Bratachari movement (meaning vow Bengali) aimed at achieving spiritual and social improvement across India. Its objective was to raise the self-esteem and national awareness of the people of undivided India regardless of their religion, caste, sex or age. Two years later he formed the local Bengal Bratachari Samity (Society).

In 1940, the year before he died of cancer, Dutt acquired a 33 acre plot of land near Joka on the outskirts of Kolkata, naming it Bratachari village. His huge collection of over 2,500 objects collected across West and East Bengal was entrusted to his Bengal Bratachari Samity. In 1961 they finally constructed a museum of folk art on the site to house his collection, naming it the Gurusaday Museum. It opened to the pubic in 1963.

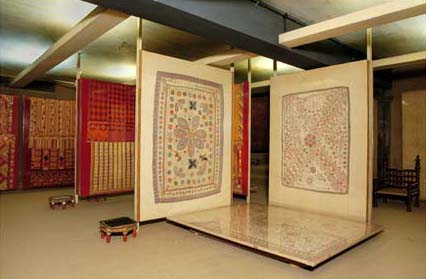

The Gurusaday Museum at Joka and its display of some 210 kanthas

We visited the Gurusaday Museum in January 1999 and were inspired, not only by the large number of kanthas on show but also by their intricacy, naivety and inspired designs. Sadly photography within the museum was forbidden. This ban on photography combined with the minimal effort that has previously been invested in promoting the museum more widely means that there is little material available to illustrate Dutt’s amazing collection. Even the few fine examples shown below do not do it justice.

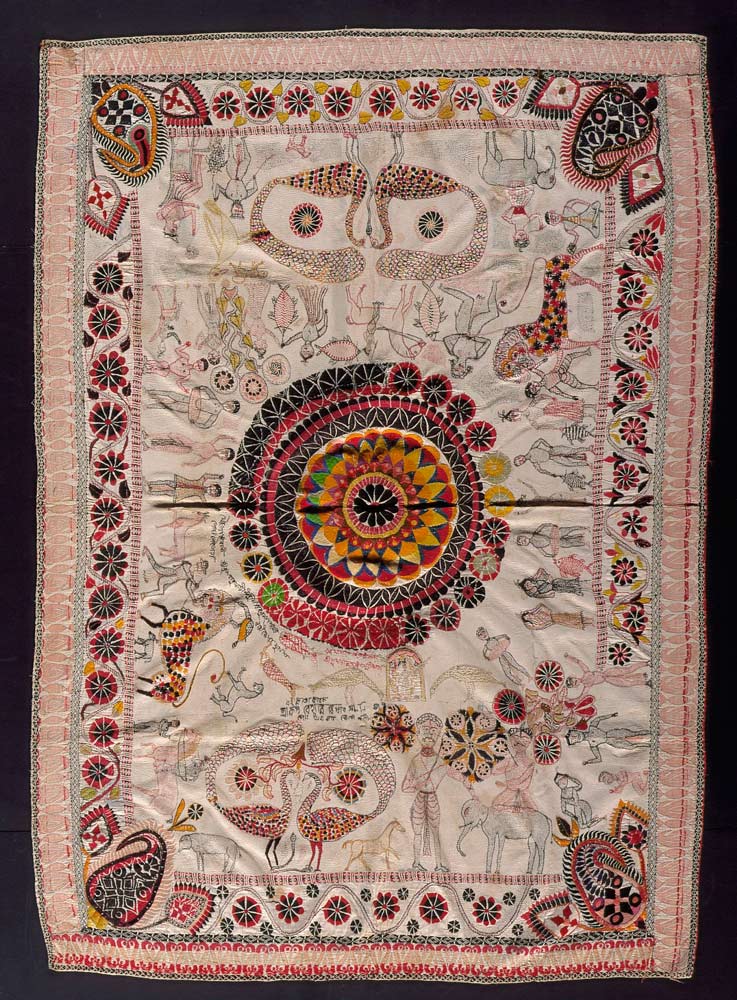

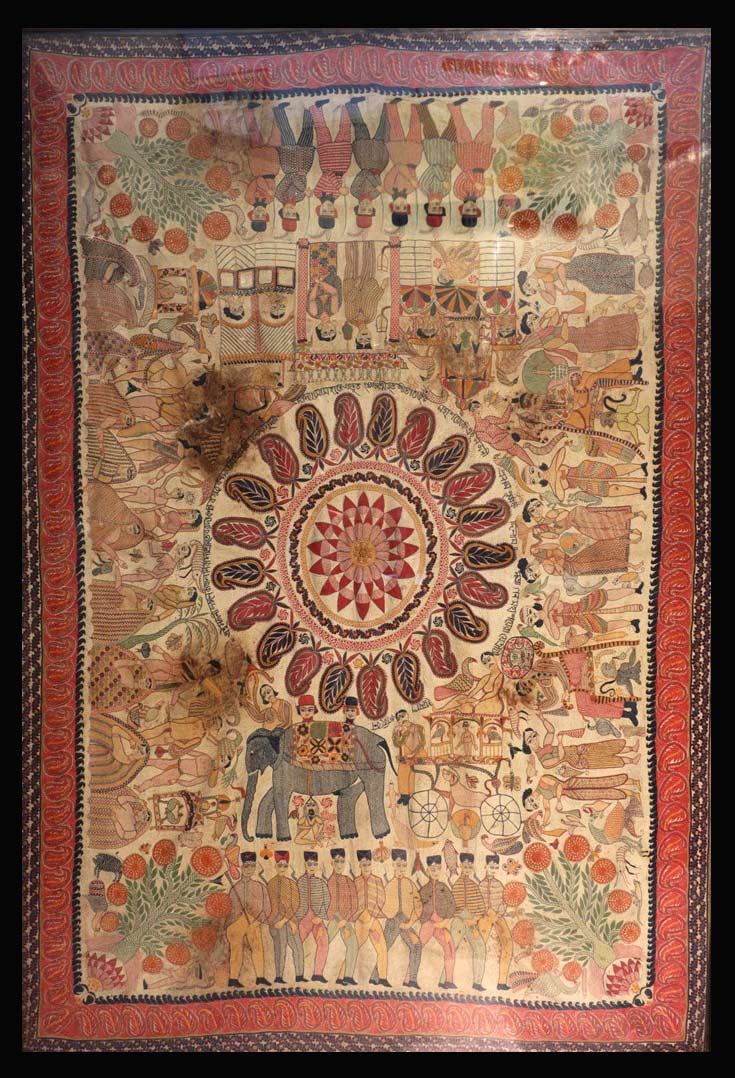

The first is a masterpiece of Bengali folk art – a sujni kantha coverlet that welcomes visitors as they enter the Gurusady Museum. It was made by Manadasundari Dasi as a gift to her father. We know this because of the text that circumscribes the central lotus roundel:

This sujni was made for Barada Kanta Basu of Jangalbadhal by his daughter, me, Srimari Manadasundari Dasi, with my own hands to honour him. Gentlemen, please forgive any mistakes that have been made.

Pika Ghosh suggests that the kantha was made around the middle of the nineteenth century, especially as it illustrates a coin bearing the shield of the East India Company – positioned just outside of the inscription on the lower right. The kantha is richly decorated with the Georgian façade of a colonial mansion, female dancers and their male attendants, female figures wearing mantles over their hair, European soldiers with sabres wearing plumed headwear, and an elephant and chariot. For a full discussion about this kantha see Ghosh 2020, 85-124.

A stunning sujni kantha made by Manadasundari Dasi in Khulna in the eastern part of undivided Bengal, nineteenth century

Many other examples in the collection were acquired in the eastern part of Bengal, especially from the regions of Faridpur, Kulna, Jessore and Dhaka.

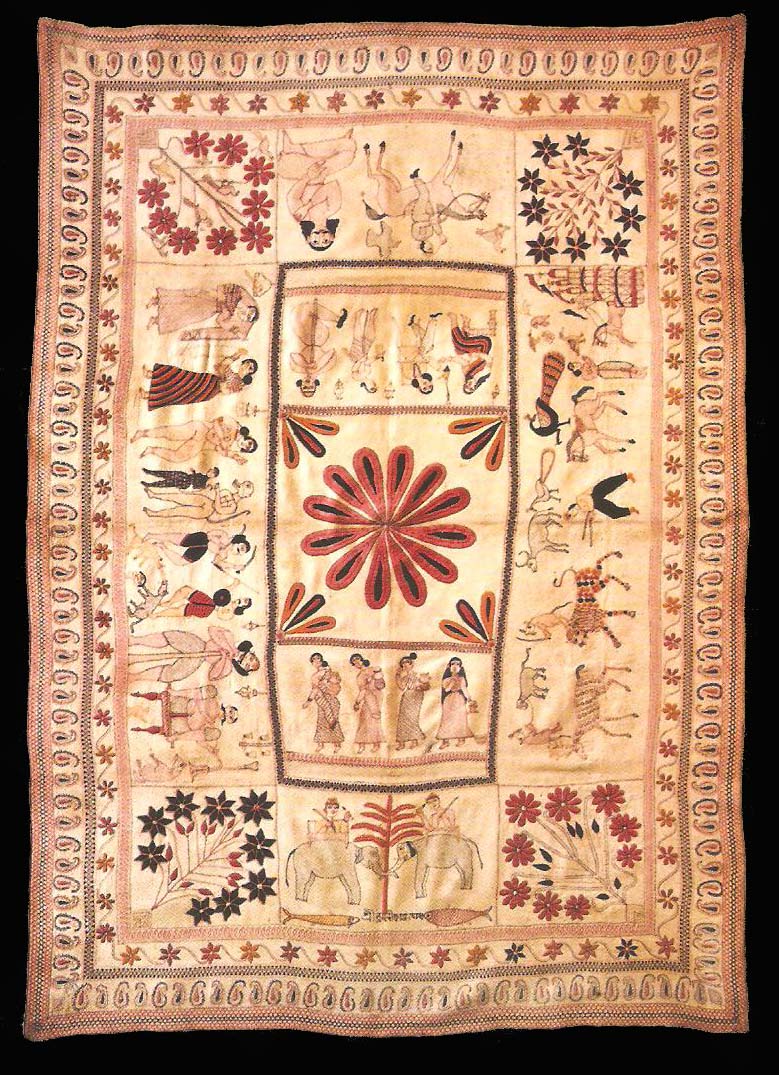

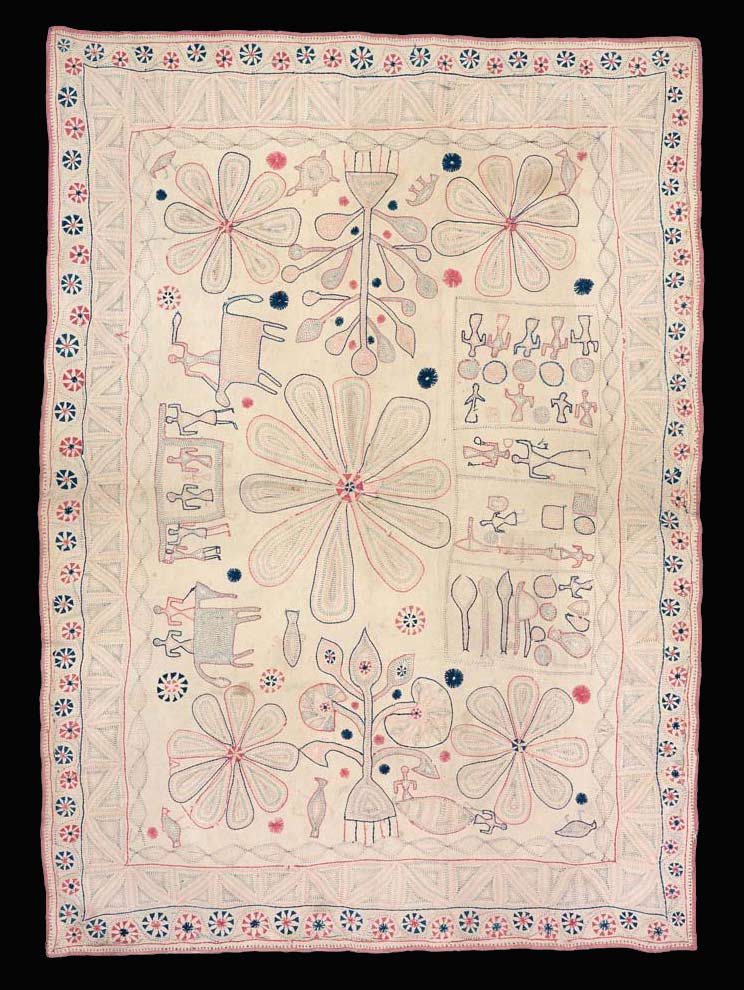

A kantha with a twelve-petalled lotus, figures and animals, nineteenth century

A bayton kantha used to cover food plates made in Khulna in the eastern part of undivided Bengal, nineteenth century

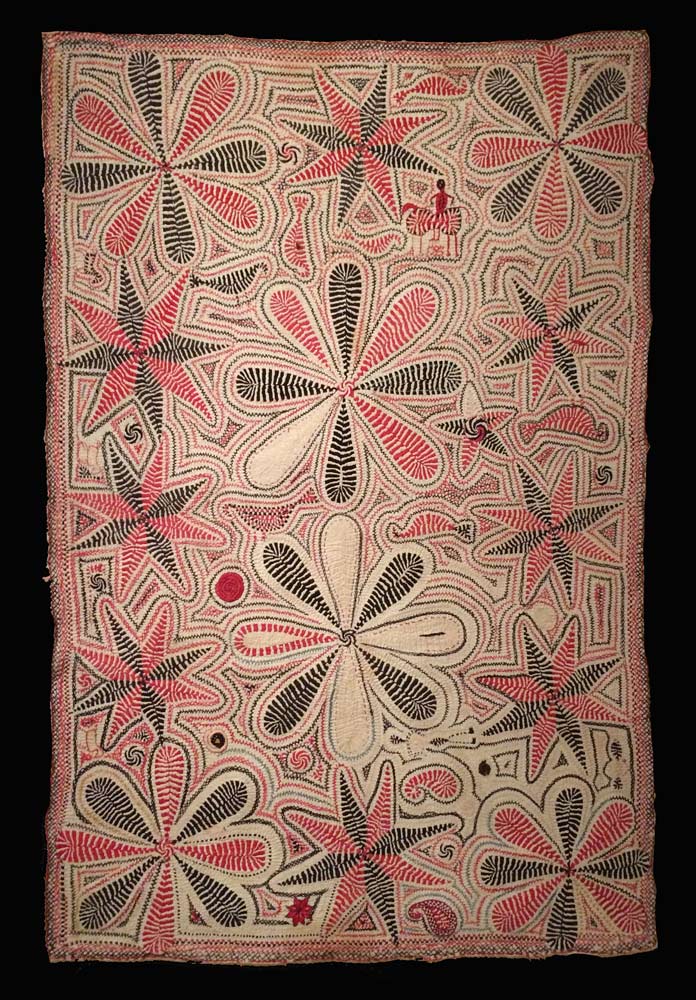

A complex kantha coverlet embroidered with a lotus design and motifs of humans, animals, flowers and a temple, nineteenth century

An arsilata kantha used to wrap a mirror, also from Khulna

Nineteenth century (70 by 20cm)

It is astonishing that during its 58 years of existence there has been no attempt to gain wider recognition for the important Gurusaday kantha collection by professionally cataloguing, photographing and publishing it.

In 2017 the Ministry of Textiles withdrew its grant to Gurusaday Museum that had been provided since 1984, forcing the Museum Curator, Bijan K. Mondal, to launch an online crowd funding exercise in an attempt to maintain the museum’s autonomy and future. From November 2017 the museum’s 13 employees began working without a salary.

With the pandemic and lockdown the museum faced a serious financial crisis as it was unable to raise funds from its workshops or online sales, forcing the staff to work without salaries.

In 2020 the branch of the Ministry of Culture responsible for museum development announced a proposal to take over the museum’s 3,300 artefacts and shift them to the more accessible Indian Museum in Kolkata. At present the museum’s future sadly remains uncertain.

Return to Top

The Calico Museum Collection

The Calico Museum of Textiles was founded in 1949 by the resourceful industrialist Gautam Sarabhai and his sister Gira Sarabhai whose family owned Calico Textile Mills, at that time a hugely successful calico manufacturing and printing works based in Ahmedabad. The museum was inaugurated by India’s first Prime Minister, Shri Jawaharlal Nehru. The Sarabhais had been inspired by the influential Sri Lankan art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy, who in 1933 had become the curator of Indian, Persian and Islamic art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

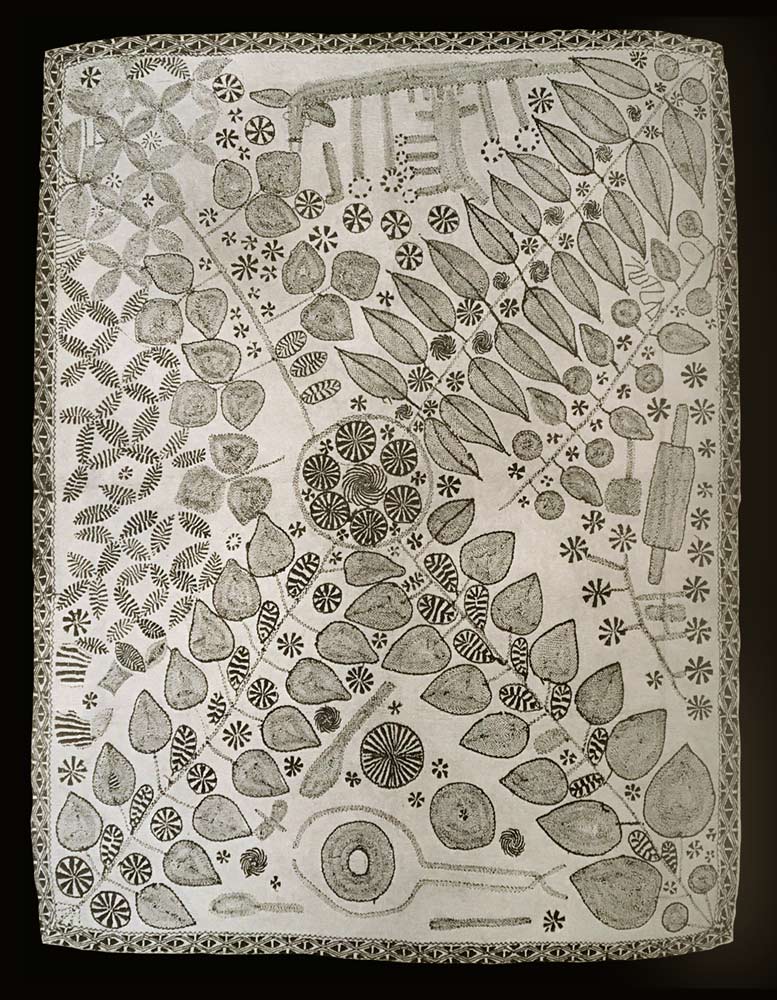

Gira Sarabhai had the financial resources to acquire fine historical textiles from across India and soon focussed the museum’s mission on the acquisition of handicraft textiles rather than industrial fabrics. In the late 1960s the Calico Museum embarked on an ambitious programme to catalogue and publish its collection, starting with its painted and printed fabrics. Its collection of embroideries was documented in 1972 by John Irwin, Keeper of the Oriental Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum with the assistance of Margaret Hall. They included just fifteen kanthas, mostly dated to the nineteenth century but lacking any provenance. Sadly the quality of textile publishing at that time was still limited and the few illustrations of complete kanthas were in black and white.

A simple lep kantha in the Calico Museum Collection, embroidered with indigo-dyed yarn depicting leaf stems, ladles, a rolling pin and a churn (135 by 102cm)

Over the past fifty years there has been little attempt to promote and publicise the Calico Museum textile collection, so most of its contents remain hidden from the wider world of textile enthusiasts.

Above and below: a few of the kanthas on public display in the Calico Museum

Return to Top

The Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

The Victoria and Albert Museum, known as the V&A, holds the world’s largest collection of decorative and applied arts with around 4½ million artefacts. This includes some 53,000 textiles most of which are European. Even so, the V&A does hold a highly important collection of Indian textiles, many of which were acquired by or on behalf of the earlier India Museum.

The V&A was founded by the British government as the Museum of Manufactures in 1852 at Marlborough House, inspired by the 1851 Great Exhibition and with the objective of promoting British manufactures. In 1854 plans were laid to move the museum to its current site and it was renamed the South Kensington Museum. It was finally renamed after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1899.

The India Museum had been founded much earlier in 1791 by the East India Company, which mainly traded in textiles. The museum’s collection had been accumulated in India by company officials and associates. In 1875 the museum was relocated from central London to a site in South Kensington. Four years later most of its contents, including its textiles, were transferred to become the Indian section of the South Kensington Museum.

In 1881 the organiser of the new Indian section, Caspar Purdon Clarke, was sent to India to expand the collections with instructions to collect objects in everyday production, not only to encourage the local manufactures of India but also to inspire British manufacturers (including textile printers) and students of art and design. Clarke's purchases included the museum's largest single acquisition of Indian textiles, with over a thousand examples of textiles and costume, a few of which were kanthas.

The Indian Section at South Kensington was eventually physically moved into the new V&A buildings in 1911 and renamed the 'India Museum'.

The V&A collection contains a few elegant traditional kanthas (par tola kanthas) with simple geometric designs on undyed cotton grounds. The first has a grid of stylised red and black rosettes on a finely rippled surface of tiny, closely spaced running stitches.

Kantha coverlet with no provenance, early twentieth century, Bengal

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Two others were only recently gifted to the museum by Karun Thakar in 2011. One small coverlet from the early twentieth century is elegantly laid out with a geometric grid of squares filled with flowers, spirals and paisley motifs.

A kantha coverlet, Bengal, early twentieth century (80 by 69cm)

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The second finely embroidered coverlet has a central floral lotus enclosed by a rectangle framed by a double border of leaves. Three tiny birds have been hidden around the edges of the inner rectangle.

A kantha coverlet with a leaf and floral design, East Bengal

First half of the twentieth century (98 x 79cm). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

These subdued kanthas contrast starkly with the two following brightly coloured sitting mats.

The first pictorial kantha is elaborately embroidered with a central lotus surrounded by four dioramas. In the top scene, Krishna the god of love is playing his flute with his lover Radha and two attendants, one holding a parasol and the other a flywhisk. The bottom scene shows a goddess, probably Lakshmi the goddess of fortune, sitting on a dias with three attendants along with the armed warrior deity Kartikeya with his peacock and her far right her means of transport, a white owl. The right hand scene has the invincible goddess Devi Chandi standing on a lion fighting the demons Chanda and Munda. The latter are in the service of the demon Shumbha and have just decapitated one of their enemies. Finally the left hand scene shows Rama and Sita enthroned together with the monkey god Hanuman lying prostrate before them. They are flanked by two attendants, one holding a parasol and the other a flywhisk.

A dramatic pictorial kantha sitting mat of unknown origin, early twentieth century, East Bengal. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The second pictorial example is less busy and has been embroidered with a large central lotus pattern, corner botehs and floral meanders.

Kantha seating mat with no provenance, early twentieth century, East Bengal (71 by 69cm). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Return to Top

The Philadelphia Museum of Art Collection

The Kramrisch Collection in Philadelphia was assembled during the 1920s and 1930s by Stella Kramrisch, an historian of Indian art and the Museum’s Curator of Indian Art from 1954 until her death in 1993. It contains examples from the districts of Khulna, Jessore and Faridpur, where the finest kanthas were produced. Though now in Bangladesh, prior to the Partition of British India in 1947 these districts had strong links and means of transportation to Calcutta.

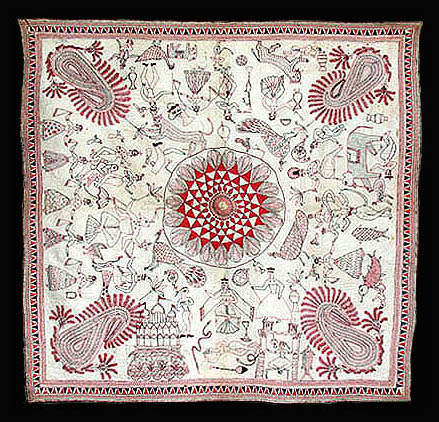

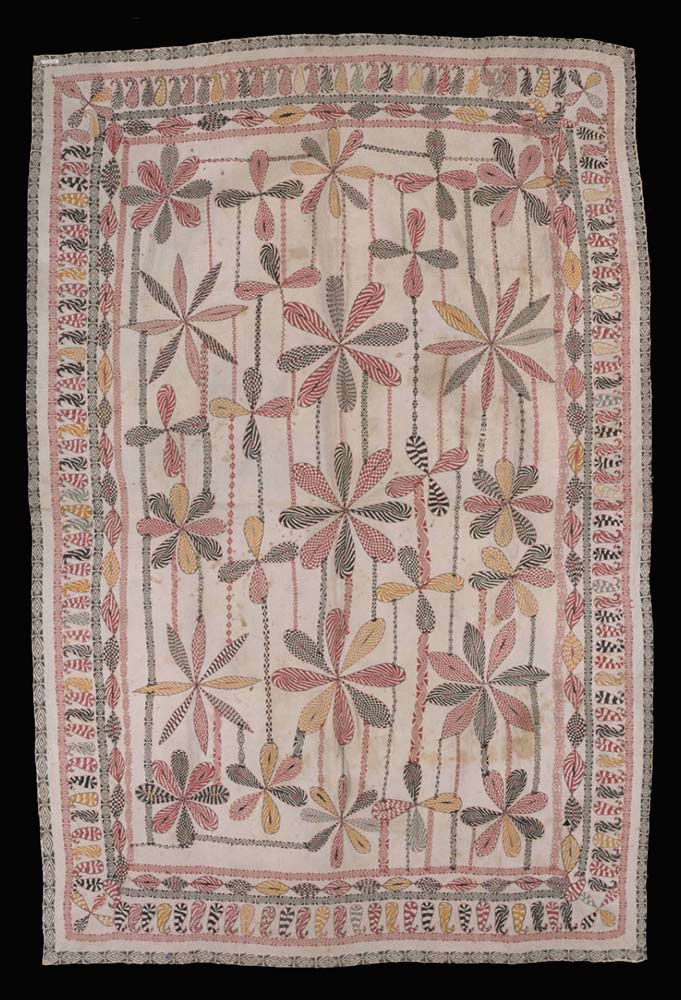

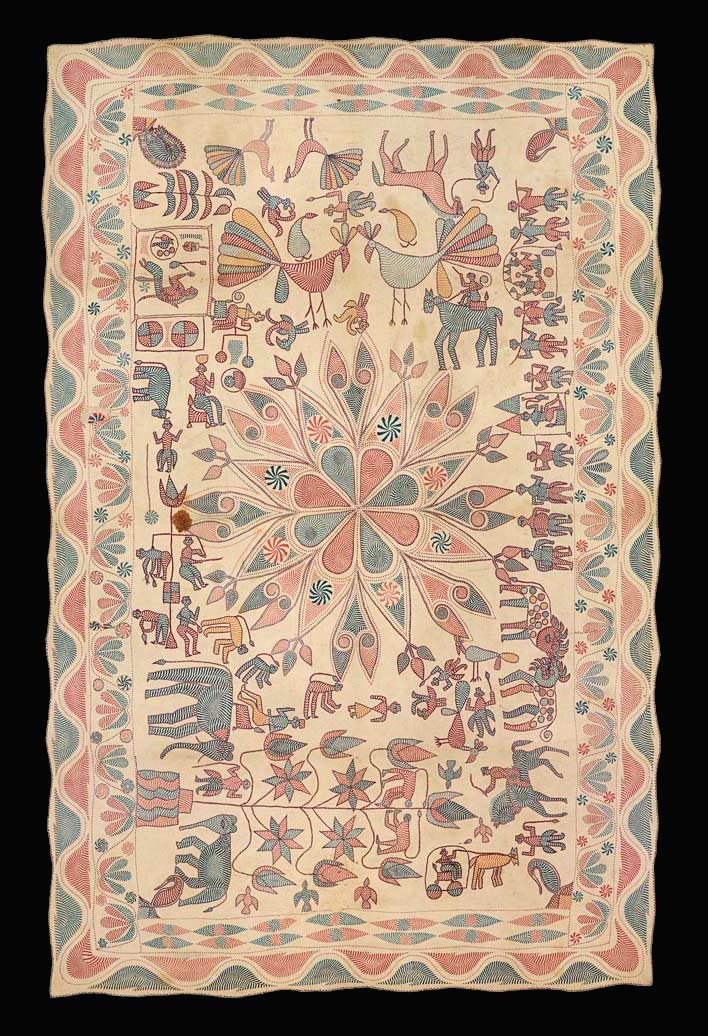

Kantha made in Faridpur District, Undivided Bengal, now Bangladesh. Dated to the second half of the nineteenth entury

In 2009 the museum held an exhibition of 40 kanthas entitled Kantha: The embroidered quilts of Bengal from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection and the Stella Kramrisch Collection of the Philadelphia Musem of Art. It contained examples from the Kramrisch Collection and a more recent collection assembled by Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz.

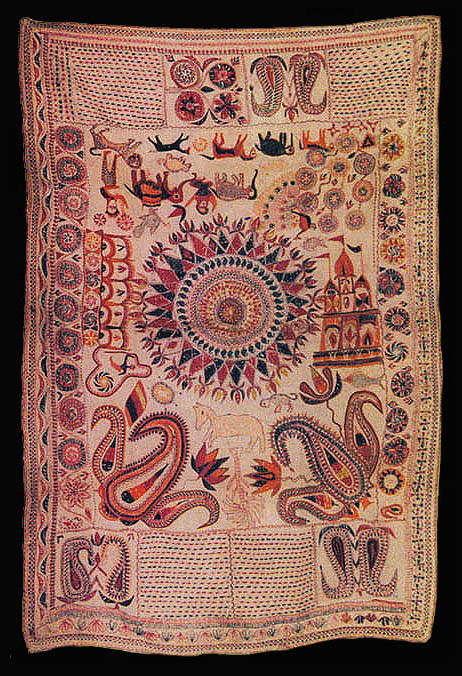

Kantha with a lotus design from Jessore, Undivided Bengal. Dated late nineteenth century. Kramrisch Collection

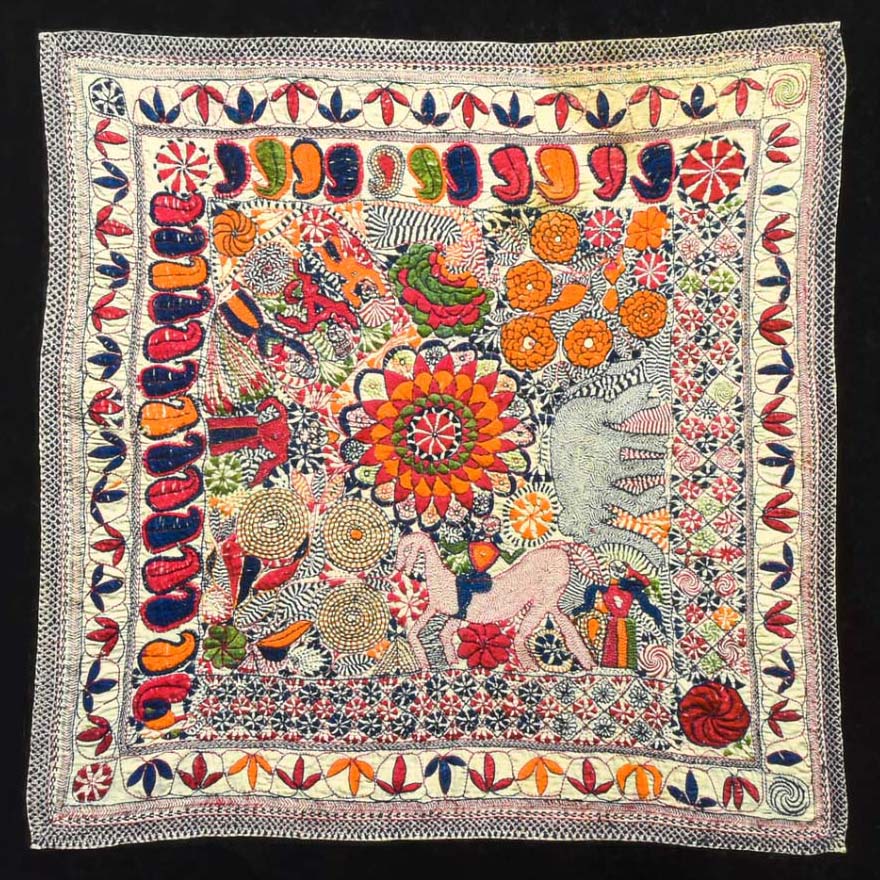

An extraordinarily colourful kantha from the Faridpur District, Undivided Bengal. Dated late nineteenth century. Kramrisch Collection

Return to Top

The Mingel International Museum Collection

The Mingel Museum in San Diego has a collection of 48 kanthas, of which 42 were donated by Courtenay McGowen, a resident of Coranado in San Diego County. McGowen bought her first kantha in India in 2005 and was so enthralled that she spent the next decade collecting them.

In 2017 the museum held Kantha: Recycled and Embroidered Textiles of Bengal, exhibited 40 kanthas from the collection. Sadly none of the exhibits have any detailed provenance.

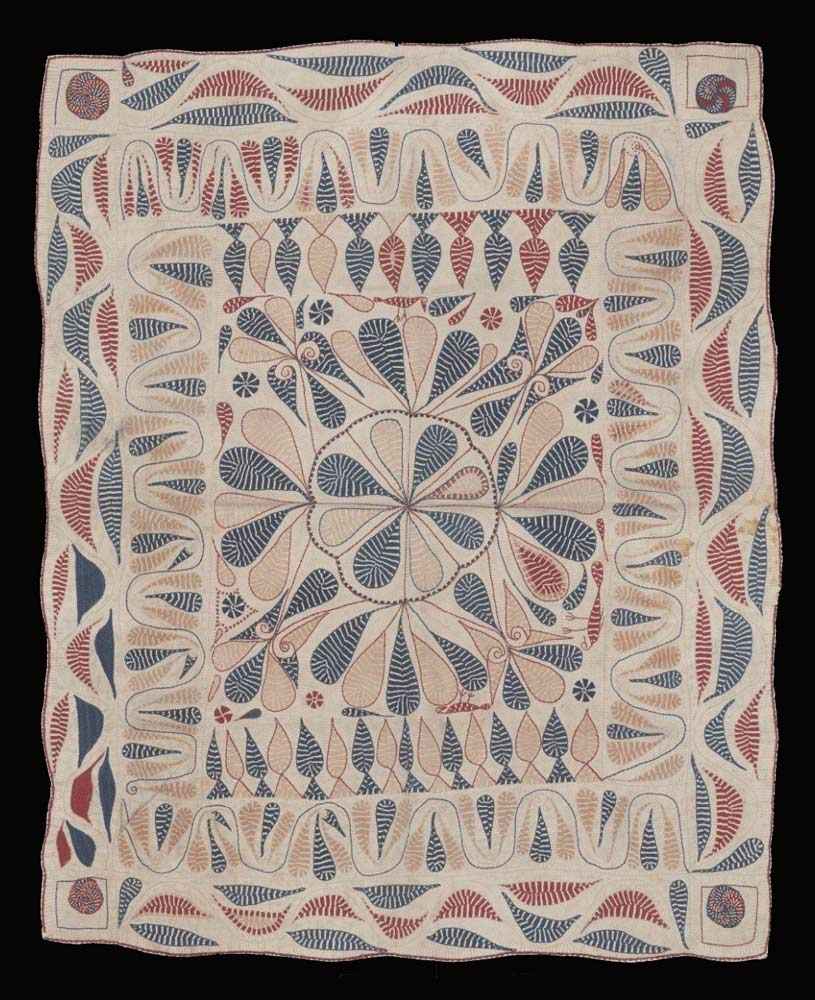

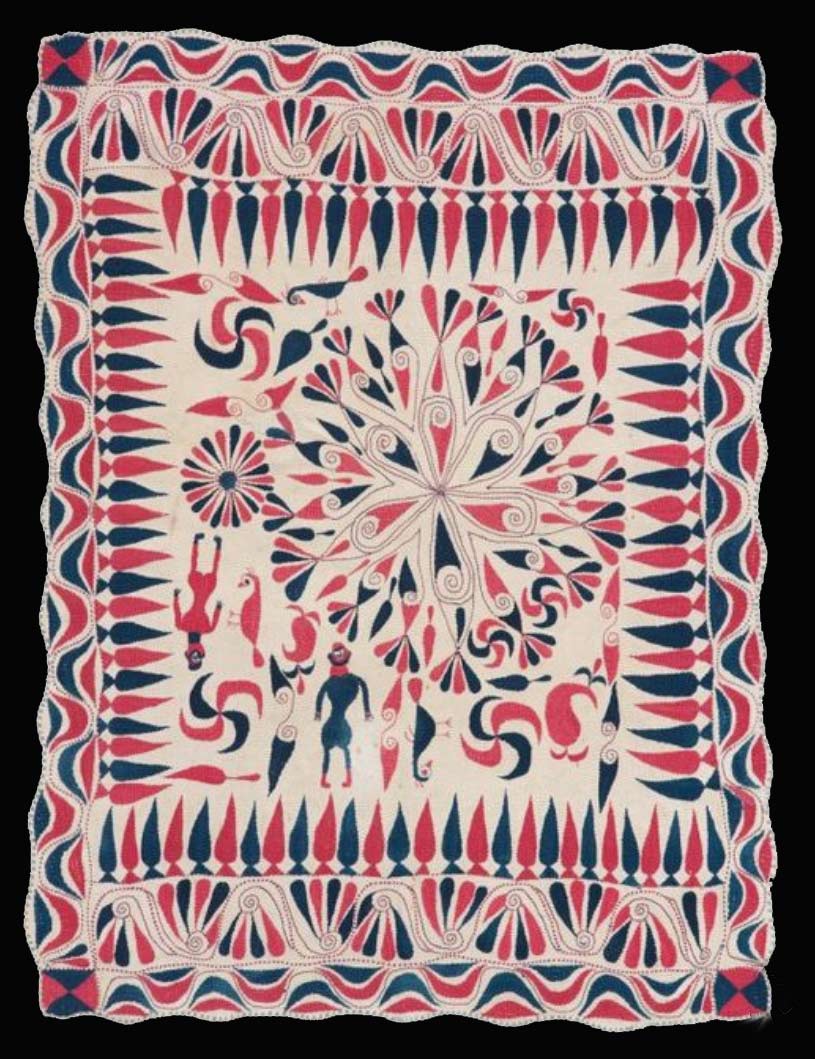

Sujni kantha bed cover or floor spread, East Bengal, estimated late nineteenth or early twentieth century (184 x 128cm)

Sujni kantha bed cover or floor spread, East Bengal, estimated late nineteenth or early twentieth century (217 x 138cm)

Baytan kantha wrapping cloth from East Bengal, early twentieth century (50 x 51cm)

Baytan kantha wrapping cloth from East Bengal, with eight-petalled flowers and eight-pointed stars, estimated late nineteenth century or early twentieth century (107 x 71cm)

Kantha with no provenance, estimated late nineteenth or early twentieth century (97 x 74cm)

Return to Top

The Richardson Collection

The Richardson Collection contains a small but varied selection of kanthas.

The first is a small embroidery gem made on a small rectangle of double-thickness hand-woven cotton cloth. It has been embroidered with naturally-dyed indigo and red (probably madder) cotton threads, the pattern consisting of a central square containing a fan-like roundel, surrounded by a sequence of concentric rectangular borders, the wider ones containing triangles and curved three-sided figures.

A rumal kantha from East Bengal, late nineteenth century (31cm x 30cm)

Richardson Collection

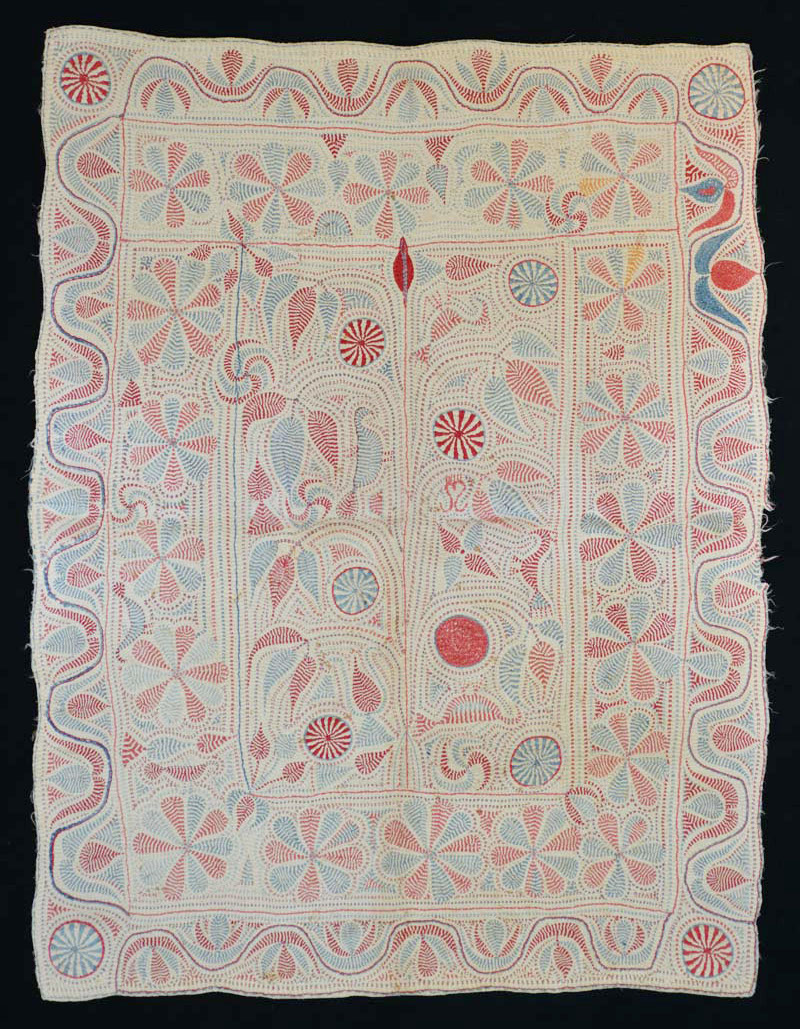

The second example is also made from a double layer of fine home-woven cotton cloth, embroidered with naturally dyed indigo and red (madder?) cotton threads.

The pattern consists of an inner rectangular field decorated with an erect flowering stem bearing drooping side shoots and leaves, the spaces in between filled with fan-like roundels. The inner field is surrounded by two borders – the first containing a row of round-petalled flower heads, the second a bold meander and alternating red and blue leaf-shaped clusters. Blue or red fan-like roundels have been placed in each corner. The pattern contains numerous irregularities and eccentricities, adding a degree of amusement and charm.

A rectangular kantha from East Bengal, late nineteenth century (66cm x 87cm)

Richardson Collection

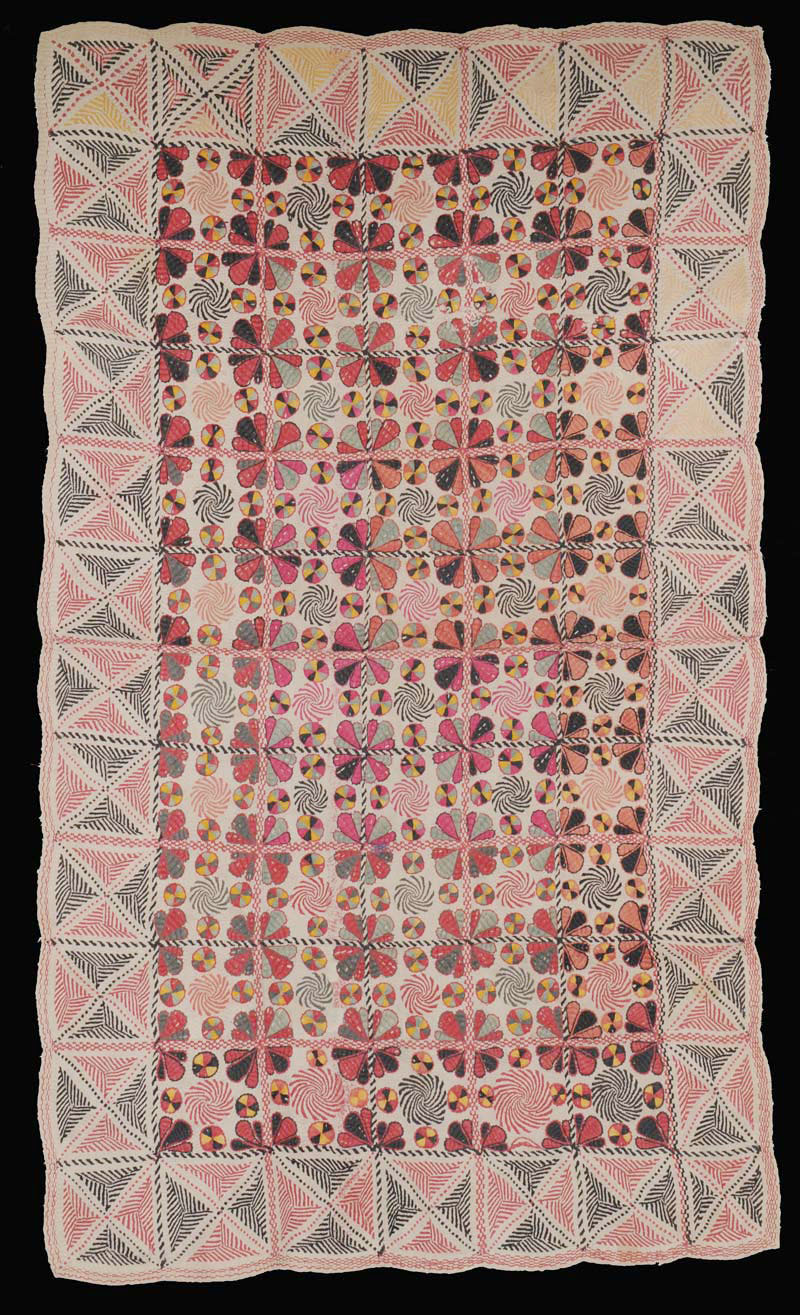

The next kantha has been mainly embroidered in satin stitch on a quilted cotton ground. The yarns appear to have been coloured with a mixture of natural and synthetic dyes.

The design is composed of a central rectangular lattice of petalled flower heads and roundels bordered by a row of diagonally segmented red and black, and sometimes yellow, squares. Note how the maker has changed the colour palette of the design partway through the embroidery.

A bayton kantha from Undivided Bengal, early twentieth century (76cm x 132cm)

Richardson Collection

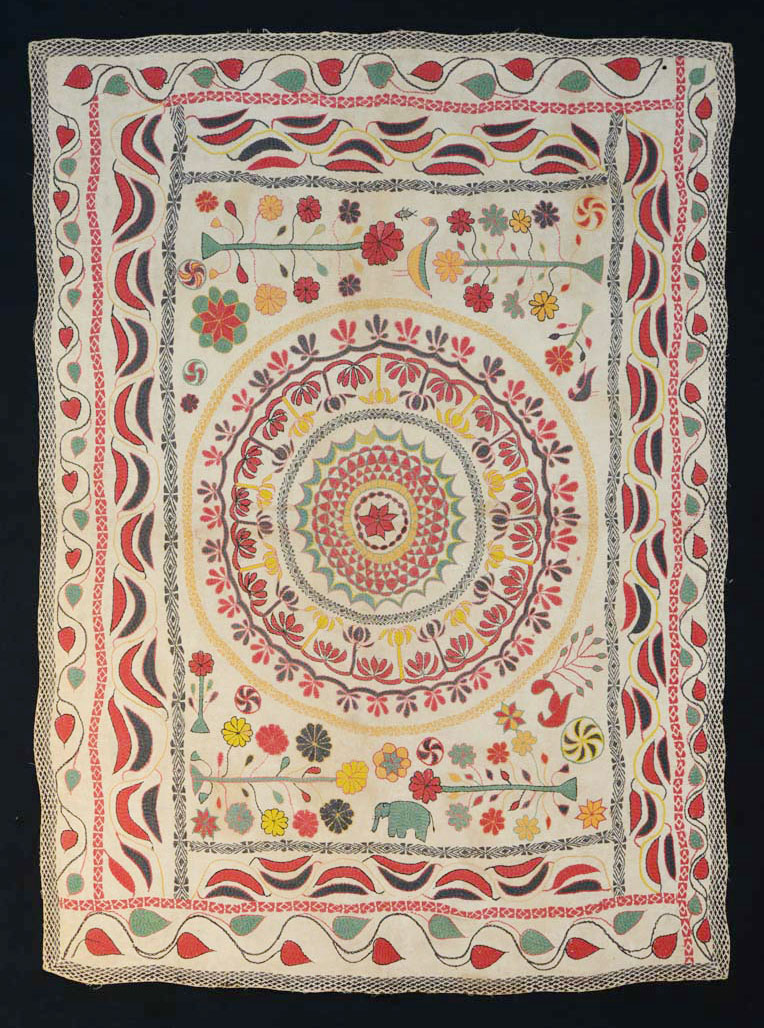

The fourth kantha example has been quilted and embroidered on two rectangles of finely home-woven cotton cloth using synthetically dyed cotton yarns.

The design consists of a central rectangular field dominated by a complex roundel containing a central lotus surrounded by round floral borders, one decorated with yellow and black palm trees. The roundel is flanked by four separate stems bearing coloured flowers and buds. The two rectangular borders are delineated by repetitive rows of small red or black motifs. The inner border contains an arrangement of red and blue peapod-shaped figures, while the outer border contains a meandering creeper with red and green spade-shaped leaves. The kantha contains several additional oddities, such as a green elephant, a peacock for prosperity, a blue bird and various other roundels and spirals.

A bayton kantha from Undivided Bengal, early twentieth century (82cm x 111cm)

Richardson Collection

The final kantha example is far more recent. It was made in 1998 at the Kantha Workshop in the southern Baghajatin suburb of Calcutta, a project supported by the Bengal Craft Association, aimed at training young women in this local craft. It was a small group of just 12 local women and was led by Ruby Paljoderi and her daughter-in-law Nandita Shipra.

A rumal kantha from West Bengal made in 1998 (50cm x 50cm)

Richardson Collection

This modern kantha has a fairly typical design with a red lotus flower in the centre, kalga motifs in each corner and four separate motifs along each side: a cat, an elephant, a peacock and a makara fish, the fish associated with the statues of religious deities. The square narrow border contains three styles of geometric embroidery.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Ahmad, Perveen, 1997. The Aesthetics and Vocabulary of Nakshi Kantha, Bangladesh National Museum, Dhaka.

Chen, Martha Alter, 1984. Kantha and Jamdani: Revival in Bangladesh, India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 11, Design, Tradition and Change, no. 4, pp. 45-62, India International Centre.

Dutt, G. S., 1939. The Art of Kantha, Modern Review, Calcutta.

Dutt, Gurusaday, 1990. Folk Arts and Crafts of Bengal: The Collected Papers, Seagull, Calcutta.

Ghosh, Pika, 2020. Making Kantha, Making Home: Women at Work in Colonial Bengal, Washington University Press, Seattle, WA.

Ghuznavi, Ruby, 2004. The Tradition of Kantha and Contemporary Trends, Asian Embroidery, Crafts Council of India.

Irwin, John and Hall, Margaret, 1973. Indian Embroideries, The Calico Museum, Ahmedabad.

Kramrisch, Stella, 1939. Kantha Textiles, Journal of the Indian Society or Oriental Art, vol. 7, pp. 141-167, Calcutta.

Kramrisch, Stella, 1949-50. Kantha of Bengal, Marg Magazine, vol. 3, no. 2, Bombay.

Mason, Daniel; Ghosh, Pika; Hacker, Katherine and Zaman, Niaz, 2009. Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Mason, Darielle, et al., 2010. Kantha. The embroidered quilts of Bengal from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection and the Stella Kramrisch Collection of the Philadelphia Musem of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven.

McGowen, Courtenay; Pal, Pratapaditya, Sidner, Rob; and Gillow, John, 2017. Kantha: Recycled and Embroidered Textiles of Bengal, Radius Books,

Parpia, Banoo and Jeevak, 2022. Kantha: Riches from Rags, Textiles Asia Journal, vol. 13, issue 3, pp. 3-15.

Riello, Giorgio, and Parthasarathi, Prasannan, 2009. The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Roy, Soumyadeep, 2020. Gurusaday Dutt: Champion of Bengal’s Folk Art, Live History India. https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/living-history/gurusaday-dutt/

Zaman, Niaz, 1993. The Art of Kantha Embroidery. University Press, Dhaka.

Zaman, Niaz, and Stevulak, Cathy, 2014. The Refining of a Domestic Art: Surayia Rahman, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 14th Biennial Symposium, Los Angeles.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 5 February 2022.