Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Sumba Part 3

Sumba from 1942 to 1945 - The Japanese Occupation

Sumba from 1945 to 1946 - The Dutch Return

The Dutch Negotiate with the Republicans – 1946

Sumba within Negara Indonesia Timur – 1947 to 1949

The Visit of Cees Taille – 1949

Sumba Prior to Independence – 1949

Sumba under Sukarno – 1949 to 1965

Sumba under Suharto’s New Order – 1965 to 1996

Sumba Post-Suharto – 1996 to 2023

Bibliography

Return to Sumba Part 1

Return to Sumba Part 2

Sumba from 1942 to 1945 - The Japanese Occupation

It took less than six months for the Japanese to occupy British Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies. The defence units of the British Indian Army and Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) were no match for their carefully coordinated combination of air power, naval forces and marine landing forces.

The Japanese attack on mainland Malaya began on 7 December 1941, just one hour before the attack on Pearl Harbour. On 16 December Japanese forces landed on British Borneo, quickly taking control of the oil refineries at Balikpapan. On 24 January Japanese forces invaded Kendari on Sulawesi, capturing the airfield. Later that February the Japanese Carrier Task Force would sail south of Sumba on its way from Sulawesi to the south coasts of Sumbawa and Java.

During January an Australian fighter squadron had used the primitive grass airfield at Waingapu as a staging post on their redeployment from Darwin to Surabaya (Bartsch 2010, 78). On 1 February fifteen Japanese fighter planes carried out an attack on Waingapu from Kendari, bombing and setting fire to a warehouse. They discovered no sign that the Allies were using the airfield at Waingapu.

Singapore was taken on the 15 February 1942, and Bali on the 19 February. Java surrendered on the 8 March, and Sumatra fell on the 28 March.

Japanese troops landing on Java, March 1942. Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

For most of 1941 the Lesser Sunda Islands had been defended by fourteen Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger (Royal Netherlands Indies Army or KNIL) brigades: eight on Flores split evenly between Ende and Larantuka, three at Waingapu on Sumba and three at Kalabahi on Alor. However in December 1941 the eight brigades on Flores were redeployed elsewhere, leaving the island undefended. Five went to Kupang, two to Atambua and one to Waingapu.

At that time Sumba had 16 autonomous regions or onderafdeeling namely: Kanatang, Waijewa, Lewa-Kambera, Tabundung, Melolo, Rindi Mangili, Waijelu, Masu-Karera, Laura, Kodi, Lauli, Mamboro, Umbu Ratu Nggay, Anakalang, Wanokaka and Lamboya. The controleur of East Sumba was Captain F. F. H. Plas and the KNIL Military Commandant was Lieutenant Schuddesbeurs (Kapita 1976b, 67).

On the 8th May 1942 Rear-Admiral Kenzaburo Hara, Commander of the Japanese 16th Cruiser Division, left Surabaya tasked with ‘Operation S’, the seizure of the Lesser Sunda Islands. The IJN minelayer Shinko Maru and the army transport Shingu Maru were escorted by two submarine chasers and carried onboard elements of the 3rd Battalion of the 47th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Major Ikumi Miyaji. On the 9 May a naval landing force quickly took control of Lombok, before moving on to Surabaya and then Flores.

On the afternoon of the 14 May an army landing force went ashore in Waingapu harbour and after securing the area were followed two days later by a special naval landing force (Bertke, Kindell and Smith 2014). The island’s KNIL defenders were soon overwhelmed. All Dutch civilians and private employees were captured and imprisoned and some of the military and civil servants were tortured (Kapita 1976a, 66). An occupation force composed of a company of troops, a communications unit, a unit of engineers, a transport unit, a medical unit and a paymaster unit was left on the island.

Over the following months the occupying force grew to about 8,000, supported by a further 8,000 Javanese and other non=Sumbanese. It was Japanese policy to recruit young local Indonesian men as auxiliary soldiers, known as heiho, to augment their military resources. Meanwhile in mid-July all the remaining Dutch citizens were rounded up and shipped to internment camps in Makassar.

The occupiers placed a heavy demand on the island's relatively poor population of about 200,000. Some insights into their effect on the Sumbanese can be gauged from the memories of the people of Kodi, which were documented by Janet Hoskins (1998, 95). They described the local Japanese commander as a tyrant. During a period of great scarcity, he demanded the local civil servants provide his troops with rice and meat. Forty head of cattle were slaughtered every month, decimating the local herd. Local people were enslaved as romusha (unpaid conscripted labourers) to construct an airstrip and defensive bunkers at Tambulaka. Skilled woodworkers and stonemasons were allowed to sleep in military barracks, but unskilled labourers were accommodated in poor quality makeshift barracks (The Encyclopaedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War 2009, 207-208). On Sumba the romusha were fed on rice and yams, but some also received sago. Many of those who received sago died, as many as 25 on one day according to one romusha's account. Villagers who did not turn up for forced labour service were fiercely beaten. Many died from overwork. Local villages were also asked to supply the Japanese troops with sexual services.

All imports of food, cloth and other materials were halted and many people were eventually reduced to wearing rags. Before the Japanese occupation, vessels of the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (Royal Netherlands Steam Packet Company) called at Sumba on average four times a month, bringing in supplies (Netherlands News 1945, vol. 12, 19). The food situation became so bad that in 1944 it became necessary to import 1,000 tonnes of rice (Sato 2000, 21).

It soon became known that conscription into the Japanese workforce was tantamount to a death sentence (Kuipers 1998, 81). In the inland region of Waiholo in western West Sumba many people escaped the Japanese by fleeing to their ancestral villages on the coast (Fowler 2002, 162).

In November 1943 the 123rd infantry Regiment of the 46th Division of the Japanese army landed on Sumba and remained for almost 18 months. They were eventually sent on to Singapore in April 1945.

As the war turned, the Japanese forces on Sumba became a target themselves. During April 1943 the 380th Bombardment Group (Heavy) of the USAAF was deployed from Arizona to the Northern Territory of Australia and placed under the command of the RAAF. It was composed of four squadrons of B-24 Liberator bombers, and soon began to conduct bombing missions across the former Dutch East Indies. One of the earliest targets was the Japanese warships moored in Waingapu harbour.

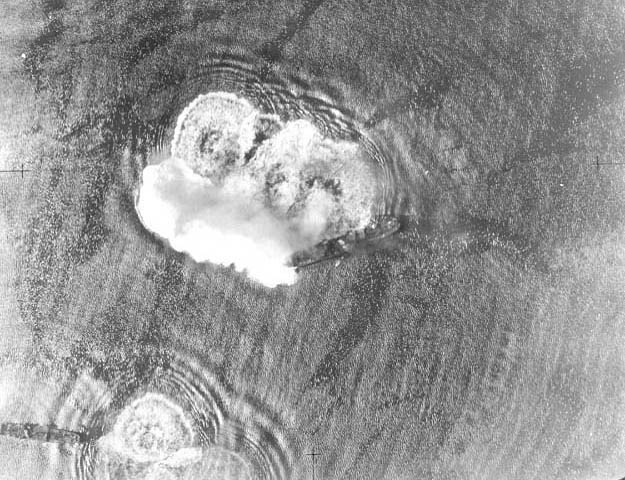

Bombing Japanese ships in Waingapu harbour on 8 June 1943

(Image courtesy of Bill Schek, 380th Bombardment Group, USAAF)

The biggest raid took place on 2-3 December 1943, when the port and town of Waingapu was bombed by over 20 B-24s. More Liberators attacked Sumba in January 1944.

The bombing of Waingapu town on 3 December 1943

(Image courtesy of Bill Schek, 380th Bombardment Group, USAAF)

On 6 November 1944 16 RAAF bombers, including four Mitchells, conducted a raid on an anti-submarine ship leaving Waingapu harbour, sinking it. They also attacked Waingapu town and its anti-aircraft units (Bennett 1995, 222). In late 1944 Captain Sato Tasuku of the Imperial Navy was transferred from Flores to Sumba.

An RAAF Catalina flying boat in flames near Sumba Island after it was forced to land because of engine trouble. The crew were rescued by another Catalina the following morning, 14 January 1945, and their plane was deliberately destroyed by machinegun fire.

A January 1945 intelligence report noted that Waingapu was then home to 941 men belonging to the 6th Guard unit of the Keibitai, the Imperial Japanese Army, and the 50th Anti-Aircraft Defence Unit (Know Your Enemy! CinCPac-CinCPOA Bulletin 11-45 1945). By then conditions on the island must have been poor. A Japanese news agency message intercepted by the Netherlands Indies monitoring service in Australia claimed that the conditions on Sumba were appalling – there was no medical service and no communication links to the ‘more civilised parts of the globe’ (The Knickerbocker 1945, 26).

An RAAF Liberator from No. 24 Squadron shot down while attacking the Japanese cruiser Isuzu near Sumba Island on 6 April 1945

Aware of their rapidly declining military position, the Japanese arranged for the republican leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta to fly to Naval Headquarters in Makassar. They were accompanied by the Java-based Naval liaison officer Sigetada Nishijima. In November 1943 during a visit to Tokyo, Emperor Hirohito had promised Sukarno and Hatta future independence in return for the provision of romusha forced labourers and food supplies. Now they had been invited to a secret five-day conference aimed at preparing the ground for an independent Indonesian state. On 29 April 1945, the Emperor’s birthday and the day on which the Americans liberated the Philippines, Lieutenant General Yoichiro Nagano, Supreme Commander of the 16th army, authorised the formation of an Investigating Committee for the Preparation of Independence (Badan Penjeldik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan, BPUPK). It would be composed of 67 representatives from across Indonesia.

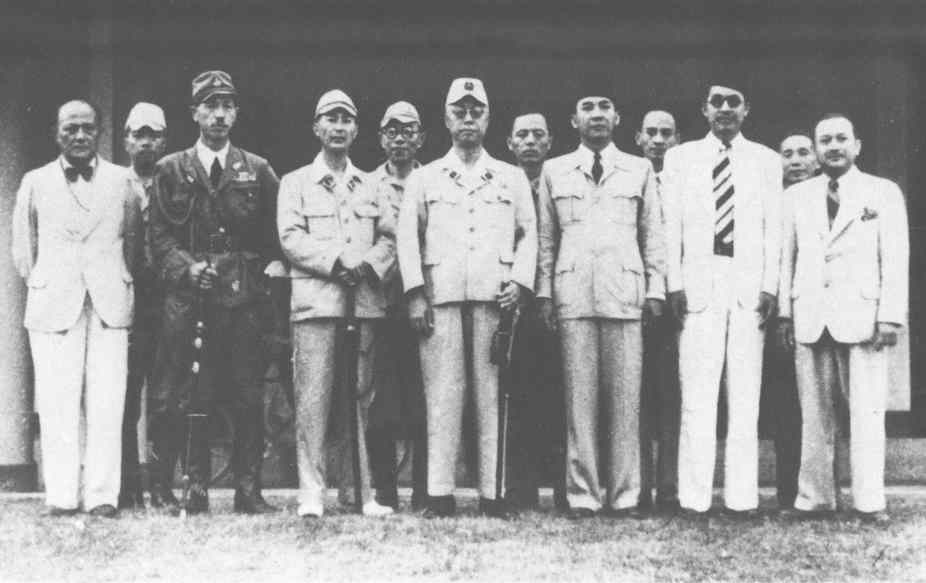

Sukarno in Makassar on 30 April 1945. From left to right: Dr G.S. Ratulangie (from Menado); Kenichi Hayashi (espionage coordinator in the pre-war Indies); Rear Admiral Tadashi Maeda; Ichiki (Naval Civil Administration), Captain Masuzo Yanagihara (Chief of the Political Bureau), Mitsuhashi (Naval Area Governor), Shigetada Nishijima, Sukarno, Sumanaig (Japanese Military Administration), Tadjuddin Noor, Tomegoro Yoshizumi and A. Subardjo.

However the Allies terminated the war sooner than the Japanese expected. On 6 and 9 August 1945 the USAF dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite this devastating attack, Allied raids on the Japanese forces based in the Lesser Sunda Islands continued.

Just hours before the USA had dropped its second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, and Soviet forces had invaded Manchuria, the leaders of the independence movement, Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta and Dr Radjiman Wediodiningrat, were flown to Saigon in a Japanese military plane. They were then driven to Dalat to meet Field Marshal Terauchi Hisaichi, Commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army. He informed them that at long last, Japan would recognise Indonesian independence. The leaders returned to Jakarta on 14 August and on the following day Emperor Hirohito finally surrendered to the Allies.

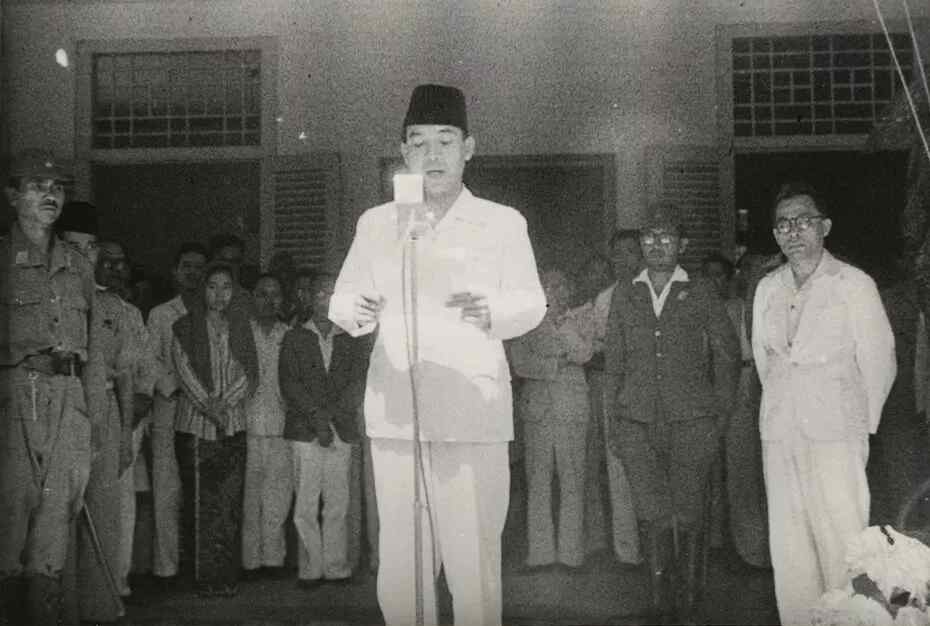

In Jakarta on 17 August Sukarno was reluctantly encouraged to announce the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence or Proklamasi Kerdekaan Indonesia and the 'five principles' that he had formulated while in exile in Ende.

Sukarno announcing his Proklamasi with Mohannad Hatta and Japanese officers, 17 August 1945. Photographed by Frans Sumarta Mendur. Dutch National Archives

Return to Top

Sumba from 1945 to 1949 - The Dutch Return

Unlike on Java and Sumatra, there had been no community participation in the armed struggle for independence in Nusa Tenggara Timur. On Sumba news of Emperor Hirohito’s surrender first became known in Waingapu on 22 August 1945. The Japanese administration on Sumba responded on 28 August 1945 by forming two civil ‘Councils for People's Security and Peace’(Dewan Urusan Keamanan dan Kesentosaan Rakyat) – one in Waingapu for the people of East Sumba and a second in Waikabubak for the people of West Sumba (Sejarah revolusi kemerdekaan 1945-49 daerah Nusa Tenggara Timur 1979, 44; Kapita 1976b, 67). In East Sumba the chairman of the council was D. A. Latuperisa and the members were C. Piry, A. Saroinsang, M. Selun, Umbu Nggaba Hungu (the Raja of Lewa-Kambera), Umbu Hapu Hambadina (the Raja of Rindi), Umbu Hina Kapita (the Raja of Mangili) and two businessmen, Lie Tiaw Pauw and Alwi Aldjuffri.

Earlier, in July 1945, General McArthur, Commander-in-Chief U.S. Army Forces Pacific, had delegated responsibility for all operations in the southwest Pacific south of the sixteenth parallel to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander Southeast Asia. Because of wartime Anglo-Dutch agreements, the British had been left with an obligation to restore the status quo in the East Indies by helping the Dutch reoccupy their former territories. British Indian forces would take responsibility for initially gaining control of Java and Sumatra, while Australian forces would take responsibility for occupying eastern Indonesia.

During September 1945 British troops began arriving on Java and Sumatra. Meanwhile the Australian army, supported by a contingent of Dutch East Indies administrators – including the returning controleur, A. H. Ruibing – took control of Ambon (Chauvel 2014, 182 and 201).

In the southeast Indies the first Australian troops arrived in Kupang on 2 September 1945 under the command of General Sir Thomas Blarney (Ardhana 2005, 328). Colonel C. C. de Rooy, the leader of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA), left Darwin on 7 September 1945 with 37 Dutch NICA officers and supporting troops, and arrived in Kupang on 11 September 1945 (Ardhana 2005, 349). He was accompanied by the Resident of Timor, Cornelis Woutherus Schüller, who had previously been interned on Sulawesi, and Lieutenant R. Westerbeek, who had previously escaped to Australia. That very same day on board HMAS Moresby, moored just offshore from the ruins of Kupang, Colonel Kaida Taitsuchi signed the formal surrender of the Japanese forces on Timor, surrendering his sword to Brigadier Lewis H. Dyke, Commander of the Australian 33rd infantry brigade.

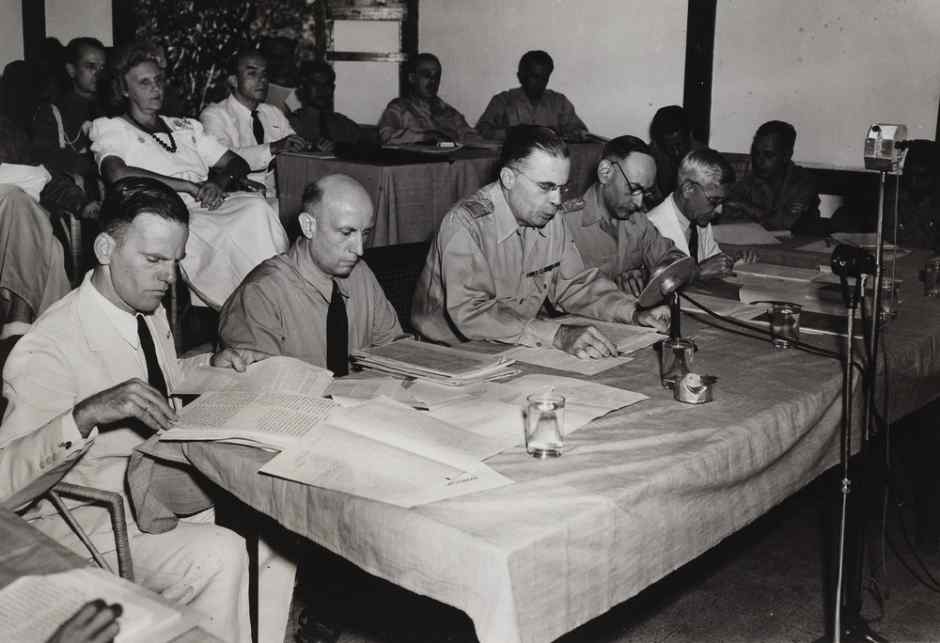

Later, on 26 September, Lieutenant General K. Yamada, commander of the Japanese 48th Division, and eight of his senior staff flew from Sumbawa to Kupang and on 3 October formally signed the unconditional surrender of the Lesser Sunda Islands in front of Brigadier Lewis G. H. Dyke on a newly made parade ground in Kupang (Farram 2004, 217).

Major J. M. Baillieu with Brigadier Dyke about to read the surrender document to Lieutenant General Yamada in Kupang on 3 October 1945 (ATE/ende-106)

NICA troops under the leadership of Colonel C. C. de Rooy quickly took over the civil administration of West Timor and the neighbouring islands, reassigning employees from the pre-Japanese era.

Between 13 and 30 October 1945 C. A. Schüller and Lieutenant R. Westerbeek conducted an inspection trip of Flores, Sumbawa and Sumba (Ardhana 2005, 349). Sumba was inspected by members of the Australian Sunforce, a detachment of the Timor Force in Kupang. Their priority was the disposal of Japanese arms and equipment and the identification of any remaining Japanese stores. One report suggests that they discovered a prison camp on the island full of women and children abandoned by their guards. The Japanese had departed in a small merchantman which was eventually stopped in the Banda Sea by an American cruiser before being escorted into Darwin.

The port and harbour of Waingapu as seen from a former Japanese observation post by members of the Australian Sunforce on 25 October 1945

Japanese anti-aircraft guns in Waingapu, 25 October 1945

Archive of the Australian War Memorial

Japanese stores and amunition being moved to the barge loading point by rail trolleys, Waingapu, 25 October 1945. Archive of the Australian War Memorial

Allied troops finally arrived at Waingapu on 8 November 1945, accompanied by Captain F. H. H. Plas, the former controleur at Waingapu at the time of the Japanese invasion. They were welcomed by Lieutenant Westerbeek. Afterwards Lieutenant Westerbeek and Lieutenant Zeeman accepted the transfer of the island’s administration from the local Japanese Commander.

Lieutenant Zeeman of the NICA interrogates ex-heiho at Waingapu

Archive of the Australian War Memorial

In December 1945 all of the Japanese throughout the Lesser Sunda Islands were despatched to a concentration camp located at Robok on Sumbawa Island (Tasuku Sat-o 1957, 120).

It seems that very few people on Sumba were aware of Sukarno’s earlier proclamation of independence. According to Allied intelligence, there was no evidence of any independence movement on the island. The Dutch played down Sukarno’s declaration, informing ex-romusha that Indonesia was not yet independent, simply stating that there had just been a rebellion in Java by a group of extremists (The Encyclopaedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War 2009, 211).

Plas soon took back his role as the Assistant Resident of East Sumba, basing himself in Waingapu, while Westerbeek became Assistant Resident of West Sumba in Waikabubak. However after Westerbeek’s wife was paralysed in childbirth, he requested a transfer to Sumbawa and was replaced by Hartstein (Kapita 19786b, 68). Sometime later Plas was also transferred to Sumbawa and was replaced by Dr. Koerts.

Return to Top

The Dutch Negotiate with the Republicans – 1946

While the Dutch faced no major obstacles in reasserting their control over most of the eastern area previously occupied by the Japanese Navy, Sumba and Flores included, this was far from the case in the west. Although a small British intelligence unit had been parachuted into Jakarta (the new republican name for Batavia) on 2 September 1945, it was not until 15 September that two cruisers, one British and one Dutch, arrived with troops and a group of NICA officials. The British were surprised that the island was firmly under Republican pemuda (youth) control and that anti-Dutch feelings were widespread.

At his headquarters in Ceylon, an alarmed Lord Mountbatten realised that any military campaign to restore Dutch control of Java or Sumatra would be disastrous. Much to the surprise of the Dutch, he refused to allow Dutch troops to reoccupy Java and Sumatra and confined British activity to just Jakarta and Surabaya. Dutch forces would only return following the departure of the British in November 1946.

In Jakarta the Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, Lieutenant Hubertus van Mook, responded to this situation on 6 November 1945 with a radical proposal. The Netherlands would recognise Indonesian national aspirations and would create a colonially-controlled central government composed of:

- a democratically elected body with a substantial Indonesian majority and

- a council of ministers headed by the Governor General representing the Netherlands, which would govern internal affairs.

At the Malino Conference held on Sulawesi in July 1946 representatives from Borneo and eastern Indonesia backed Dutch proposals to create a federal United States of Indonesia. This would be composed of the Republic of Indonesia on the one hand and the states of Borneo and the Greater Eastern State (Negara Timur Raya) on the other, the latter closely linked to the Netherlands. The Dutch argued that the autonomous eastern areas had been self-created by their indigenous inhabitants and enjoyed a high degree of self-government. Van Mook’s federal strategy was aimed at maintaining the colonial relationship by ensuring eastern Indonesia was isolated from the Republic, thereby providing a counterweight to it and its demand for total independence from Holland.

Lieutenant Hubertus van Mook at the Malino Conference, July 1946

On 2 September 1946 the Dutch established a four-member Commission-General, headed by a former Dutch Prime Minister, to set up a new political structure for the Dutch East Indies. On 7 October 1946 the commission travelled to Jakarta to begin negotiations with a delegation from the Republican movement. This first led to the agreement on 14 October for a ceasefire in Java and Sumatra. In November the negotiations moved to the village of Linggadjati south of Cirebon, resulting in the Linggardjati Agreement, which accepted the existence, although not the legality, of the Republic of Indonesia in Java, Madura and Sumatra.

Professor Willem Schermerhorn, former Prime Minister of the Netherlands, UK facilitator Lord Killearn and independence leader Sutan Sjahrir signing the truce agreement in Batavia, 14 October 1946

On 24 November 1946 all of the Rajas from the 16 onderafdeeling of Sumba were called to a meeting in Waingapu with the Resident of Timor, C. W. Schüller, Assistant Resident Dr. Koerts, Assistant Resident Hartstein and controleur Woundstra (Kapita 1976b, 54). A presentation was made explaining the draft Linggardjati Agreement and its consequences. On the 26 November 1946 they agreed to form a joint government of the Rajas, known as the Sumba Island Federation. It was to be governed by a Council of Rajas, the first Chairman of which was the Raja of Mamboro, Timotheus Tunggu Bili.

The Dutch state of Negara Indonesia Timur, formed in 1946 and dissolved in 1950 (Wikimedia Commons)

Following a further conference on 7 December in Denpasar, organised by Governor-General Lieutenant Hubertus van Mook, the Dutch imposed the new federal structure unilaterally, without consulting the leaders of the Republic of Indonesia. On Christmas Eve 1946 the Greater Eastern State, Negara Timur Raya, was renamed the State of Eastern Indonesia, Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT). Governed by the Dutch from Makassar, it would encompass 13 autonomous regions or daerah including Sumba, Flores and the other Lesser Sunda Islands, as well as Sulawesi and Maluku (Ricklefs 2008, 276). It would be ruled by a parliament in Makassar with seventy delegates headed by a President, the first being Tjokorde Gde Rake Sukawati, a Balinese nobleman and government official from Ubud (Gde Agung 1996, 131). However, only fifty-five delegates were elected, half of whom were civil servants employed by the Dutch, and the Dutch East Indies authorities still retained important powers. Sumba was represented by the Chairman of the Council of Rajas, Timotheus Tunggu Bili, Raja of Mamboro, and the civil servant Leonardus Lede Kalumbang as a people's representative.

Some of the delegates at the Denpasar Conference: second on the left, Ide Anak Agung Gde Agung from Ubud, Bali, centre Governor-General Hubertus van Mook, fourth from right Tjokorde Gde Rake Sukawati from Bali, and third from right Dr Onvlee from the Protestant Christian Group, Sumba

The plan was that once the regional governments were established the existing five regencies, one of which was Timor and its Islands (Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba, etc.), would automatically cease to be functional.

Return to Top

Sumba within Negara Indonesia Timur – 1947 to 1949

Some of the independence leaders fought bitterly against the Linggadjati Agreement and delayed its ratification by four months (Steiner 1947, 629). It was finally signed in Jakarta on 25 March 1947 and accepted that the Republic of Indonesia had authority over Java, Madura and Sumatra. It proposed that both sides would swiftly work towards establishing a federal United States of Indonesia. However the Dutch and the republicans were interpreting the agreement from radically different perspectives and on 21 July 1947 the Dutch government revoked the accord and launched Operation Product, a short military campaign against the Republic of Indonesia to seize the most important economical areas on Java and Sumatra, including access to their supplies of oil, sugar and rubber. This action was heavily criticised internationally, especially by counties otherwise sympathetic to the Netherlands, such as the UK and the USA.

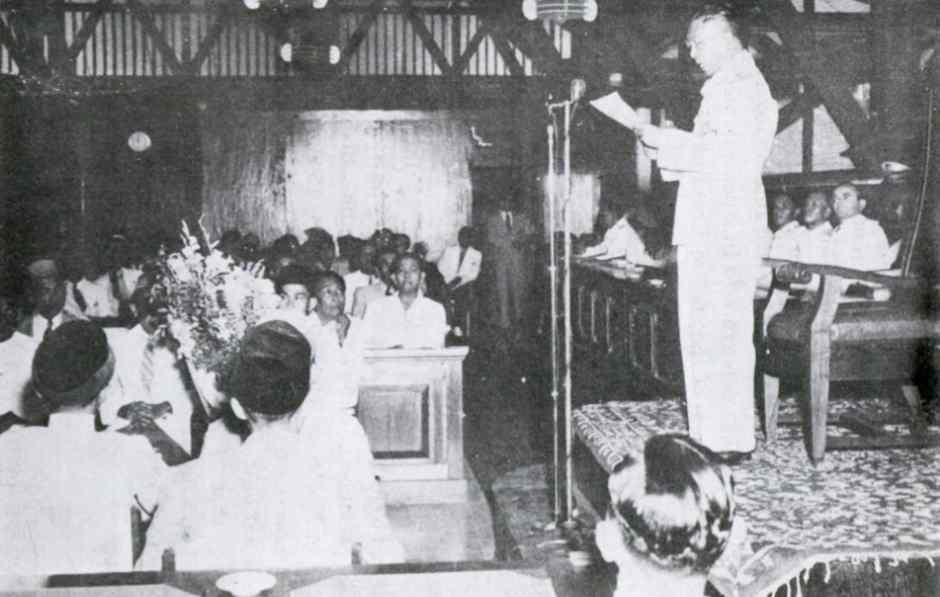

With the Dutch focussed elsewhere, Negara Indonesia Timur and Sumba were essentially left to govern themselves. The first session of the NTT legislature was held in Makassar on 22 April 1947.

President Sukawati, officially opening a session of the parliament of the State of Eastern Indonesia

Consequently, the years 1947 and 1948 were relatively uneventful on Sumba.

In 1946 Christian converts on Sumba left the Reformed Calvinist mission and in mid-January 1947 established their own independent Sumba Christian Church (Gereja Kristen Sumba or GKS) in Payeti. At that time local school management still remained under the control of Dutch and German missionaries. The GKS set about developing its own schools by establishing YAPMAS, Yayasan Persekolahan Masehi Sumba, the Sumba Christian School Foundation (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 331). They also set up vocational training courses in the field of agriculture, opening an agricultural school in Lewa. In 1948 GKS arranged for the engineer B. Abels to come to Sumba to head the development of agricultural training.

By now the pro-Republican movement was gaining support among the Negara Indonesia Timur political establishment. On 30 December 1947 the leading republican, Arnoldus Mononutu, set up the Indonesian Independence Movement Association (Gaboengan Perdjoeangan Kemerdekaan Indonesia or GAPKI) in Makassar. In a letter addressed to van Mook dated 10 January 1948, President Sukawati suggested that it was necessary to provide a place for pro-Republicans within the NIT parliament.

In 1948 Umbu Hermanus Rangga Horo, the Raja of Kodi, was appointed Chairman of the Sumba Island Federation. In the same year Umbu Leonardus Lede Kalumbang, the Raja of Laura, was elected Chair of the Sumba Island People's Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Pulau Sumba) and also a Member of Parliament for the State of East Indonesia (Kapita 1976b, 329). Umbu Hermanus Rangga Horo became a Member of Parliament for the State of East Indonesia the following year.

Umbu Hermanus Rangga Horo, Raja of Kodi and Chairman of the Sumba Island Federation, 1947-1950. Archive Department of Nusa Tenggara Timur

In July 1948 the Resident of Timor, C. A. Schüller, was replaced by A. Verhoef. On 9 December 1948 the entire cabinet of Negara Indonesia Timur resigned in protest about a Dutch atrocity in which hundreds of men were summarily executed by the Dutch military in the village of Rawagede in West Java.

Then on 18 December 1948 the Dutch launched another surprise attack on the Republic called Operation Kraai, occupying the major towns on Java and Sumatra and capturing the senior republican leaders including Sukarno. Internationally this action was seen as a major political blunder. On 22 December the USA announced the suspension of Marshall Plan aid to the Netherlands and on 24 December 1948 the UN Security Council called for a ceasefire and the release of Sukarno and the other political prisoners.

One month later, on 23 January 1949, the Indian Prime Minister Nehru summoned a conference of Asian countries in New Delhi and forwarded its concluding resolution to the Security Council. It demanded the formation of an interim government on 15 March 1949, composed of the representatives of the Republic and of non-Republican territories; that elections for a Constituent Assembly be completed by 1 October 1949, and that power over the whole of Indonesia be completely transferred by 1 January 1950. On 28 January 1949 the Security Council passed a further resolution urging the Dutch to cease fire immediately and generally comply with the terms of the New Delhi resolution.

Return to Top

The Visit of Cees Taillie – 1949

We have been left with a small photographic record of Sumba in early 1949 thanks to the 28-year-old Dutch soldier Cees J. Taillie. He had been sent to Indonesia as a member of the occupational force in 1946, but in September 1947 was recruited into the Army Contacts Service as a photographic reporter covering Negara Indonesia Timur. Because this region was completely quiet from a military point of view, he was able to travel widely, visiting both East and West Sumba during the month of February 1949.

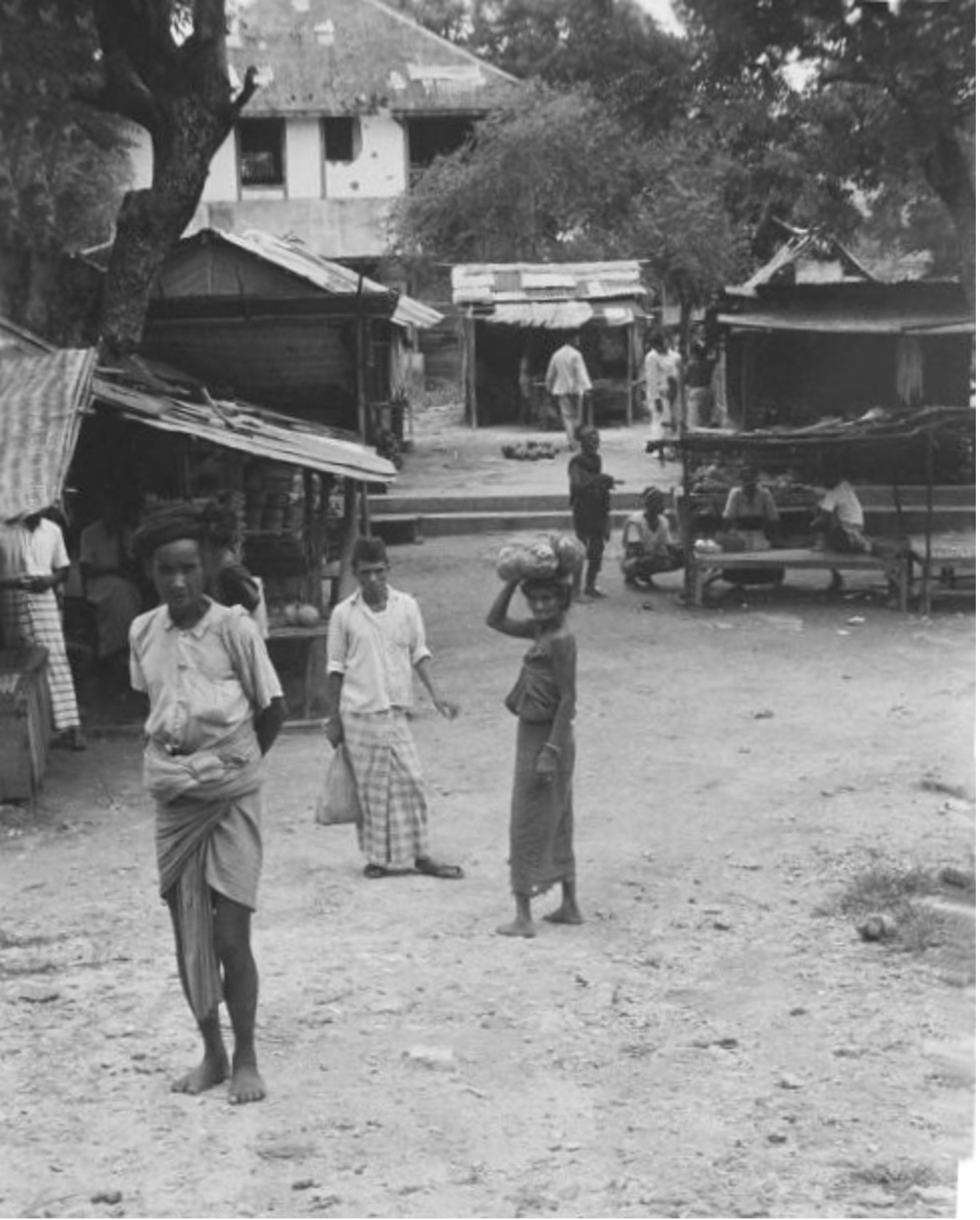

Above: Waingapu market, photographed by Cees Taillie on 25 February 1949

Below: View of the harbour and pier at Waingapu, 25 February 1949

The KLM office in Waingapu, 25 February 1949

Abandoned Japanese anti-aircraft guns at Waingapu, 1949

A group of Sumbanese, mainly men, gathering somewhere between Waingapu and Waikabubak, February 1949

Young girls dancing during the construction of a new house, February 1949

A Dutch soldier passes a group of market vendors by a Chinese school in Waikabubak, Cees Taillie, February 1949

Houses and stone graves at an unknown village on Sumba, Cees Taillie, February 1949

Taillie's photographs illustrate a rural island with a minimal level of infrastructure, whose people are still following a very simple and traditional lifestyle.

Return to Top

Sumba Prior to Independence – 1949

On 12 January 1949 the government of the State of Eastern Indonesia (NIT) was reinstated, its second cabinet led by Prime Minister Ide Anak Agung Gde Agung with Izaak Huru Doko as its Minister of Information. Following the disastrous Dutch military action in December, the attitude of his cabinet had swung firmly in favour of the Republic of Indonesia. Twelve days later his cabinet proposed the speedy introduction of a free and sovereign Federal Republic of Indonesia. Over the following months Anak Agung Gde Agung turned out to be a highly effective diplomat, negotiating with all sides in an attempt to create an independent federal state. His most important contribution was the formation on 15 July 1948 of the Bijeenkomst voor Federale Overleg or BFO (Federal Consultation Meeting), a forum for deliberations between the government of the Republic of Indonesia, the autonomous states and regions, and the Dutch government.

The BFO quickly organised the Inter-Indonesian Conference which, during July and August 1949, brought together representatives from the Republic of Indonesia and the other states and autonomous regions of Indonesia to prepare for a Round Table Conference.

Up to this time Sumba had been governed as one of the 13 daerahs (regional administrations) within Negara Indonesia Timur. Sumba consisted of 16 swaprajas (swa meaning autonomous and praja meaning governing), each lead by an aristocratic Raja:

| Swapraja | Raja |

| Lewa-Kambera | Umbu Nggaba Hunga |

| Kanatang | Umbu Djangga Tera |

| Tabundung | Umbu Hunga Wohangara |

| Melolo | Umbu Nggaba Humarta |

| Rindi Mangili | Umbu Hapu Hamba Dima |

| Waijelu | Umbu Kambaru Windi |

| Masu-Karera | Umbu Maramba |

| Umbu Ratu Nggay | Umbu H. Hudang/Umbu Tipuk Marisi |

| Anakalang | Umbu Remu Samapali |

| Lauli | Umbu Sabaora |

| Lamboya | Umbu Songalero |

| Wanokaka | Umbu Goling Manjoba |

| Mamboro | Umbu Tunggu Billi |

| Waidjewa | Umbu Bulu Engge |

| Laura | Umbu Leonardus Kalumbang |

| Kodi | Umbu Hermanus Rangga Horo |

(Source: Propinsi Sunda Ketjil 1959)

During 1949 the chairmanship of the Council of Rajas passed from Umbu Rangga Horo to Umbu Tipuk Marisi, the Raja of Umbu Ratu Nggay (Kapita 1976b, 68).

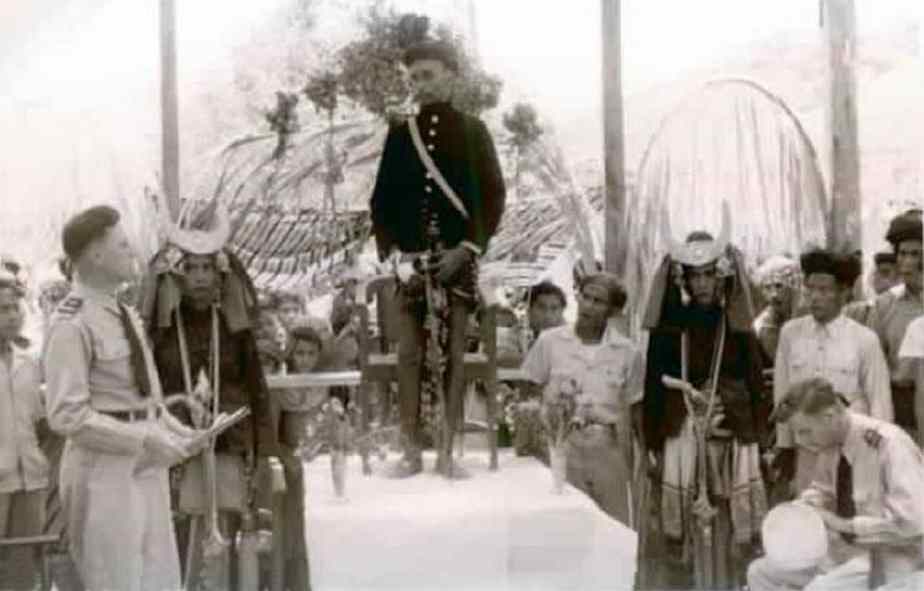

The Raja of Rindi, Umbu Hapu Hambandina, with Dutch officers in Parai Yawang, Rindi in 1949

In the same year moves were undertaken to decentralise governance by transforming Sumba, Flores and the other 11 daerahs into autonomous regions (Farram 2004, 251). On 1 October 1949 Izaak Huru Doko was deputised to oversee the transfer of civil authority from the Dutch to the local officials across Eastern Indonesia. The daerah were then grouped into three State Commissariats (Bagus Wirawan 2008, 56):

- the Southern State Commissariat encompassing Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Sumba, Flores and Timor;

- the Middle State Commissariat covering South Sulawesi and South Maluku; and

- the Northern State Commissariat covering the Minahasa area, North Sulawesi, Sulawesi Central, Sangihe & Talaud, and North Maluku.

Return to Top

Sumba under Sukarno – 1949 to 1965

The Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference was finally held in The Hague and lasted from 23 August 1949 to 2 November 1949. It included representatives from the Republic, the Netherlands, and the Dutch-created federal states. The Netherlands agreed to recognise Indonesian sovereignty over a new federal United States of Indonesia. It would include all of the territory of the former Dutch East Indies, with the exception of Netherlands New Guinea. Queen Juliana finally signed the document transferring sovereignty from the former Netherlands East Indies to the new Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia Serikat) on 27 December 1949 in Amsterdam.

The final session of the Round Table Conference on 2 November 1949

On Sumba in early 1950 Umbu Tipuk Marisi, the Raja of Lawonda, became the next Regional Head and Chairman of the Council of Rajas, the most powerful politician on the island. Later, on 22 August 1950, the Council of Rajas was disbanded and replaced by a People’s Regional Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah), the membership of which remained in the hands of the aristocracy. It was around this time that the first public secondary school was opened on Sumba, located in Waingapu.

The Republic of the United States of Indonesia was short-lived since many local politicians objected to the federal system that linked the Republican west to the Dutch-created states in the east. Between 27 December 1949 and August 1950, the majority of federal states agreed to dissolve and incorporate themselves into the Republic of Indonesia. On 17 August 1950, five years after his initial declaration of independence, President Sukarno could announce that the federal state no longer existed. The Republic of Indonesia had emerged as a unitary state with all of its territories governed by a centralised government. Its component parts were separated into ten provinces, one of which was Sunda Kecil or the Lesser Sunda Province, which included Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Sumba and Timor. Later in 1954 Sunda Kecil Province was renamed Nusa Tenggara Province.

During the Sukarno era little attention was paid to Sumba. Most of the political changes that occurred were the result of the implementation of national policies aimed at extending government control down to the regional level. However, at a local level, the Rajas retained their powers until the early 1960s.

During 1958 the Indonesian government reorganised the whole structure of regional government. On 14 August the Province of Nusa Tenggara was split into three smaller Level I autonomous provinces, namely Bali, Nusa Tenggara Barat and Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT), the latter including Sumba, Flores and Timor.

On 13 December 1958 Sumba was split into two Level II regions or kabupaten (regencies), East Sumba (Kabupaten Sumba Timur) and West Sumba (Kabupaten Sumba Barat), exactly as before. L. D. Dapawole was appointed the regional head of East Sumba Regency, while Leonardus Kalumbang was appointed the regional head of West Sumba Regency.

East Sumba was subdivided into seven autonomous swaprajas: Kanatang, Lewa-Kambera, Tabundung, Melolo, Rindi-Mangili, Waijelu and Masu-Karera.

West Sumba was subdivided into nine swaprajas: Laura, Wewewa, Kodi, Lauli, Mamboro, Umbu Ratu Nggay, Lamboya, Anakalang, and Wanokaka

On 5 June 1962 the Governor of East Nusa Tenggara issued decree number 66/1/35 transforming the self-governing swaprajas of NTT Province into 64 kecamatan or subdistricts, each headed by a camat. This stripped away the political power of the Rajas and transferred it to educated, government-appointed officials. Sumba remained split into two kabupaten, East Sumba with five kecamatan and West Sumba with eight kecamatan. The kecamatan were further divided into desas (village regions) based on geography rather than genealogy or clan traditions. Sumba as a whole was split into 234 desa with a total population of 449,990 people. Although the objective of this reorganisation was to extend government control down to the local level, the newly appointed government officials faced the difficulty of challenging the power and authority of the traditional regional Rajas.

In East Sumba the five new kecamatan were Lewa-Kambera, Kanatang-Kapunduk, Tabundung, Pahunga Lodu and Masu-Karera. The swaprajas of Umalulu, Rindi-Mangili and Waijelu had been grouped into the new kecamatan of Pahunga Lodu (literally ‘east day’, meaning where the day begins), with Kabaru as its capital (Kapita 1976b, 155). This turned out to be too large, and in 1965 it was split into Kecamatan Rindi-Umalulu, composed of the former swaprajas of Rindi and Umalulu, and the smaller Kecamatan Pahunga Lodu, composed of the former swaprajas of Mangili and Waijelu, with Ngalu as its capital (Kapita 1976b, 155).

On 20 July 1963 West Sumba was reorganised into seven kecamatan: Kodi, Laratama, Wewewa Barat, Wewewa Timur, Lauli, Wanokaka and Katikutana (formed from Anakalang and Umbu Ratu Nggay).

Following the promulgation of law number 18 in 1965, the Regency of East Sumba was divided into six kecamatan, namely Kanatang-Kapunduk; Lewa-Kambera; Tabundung; Rindi-Umalulu; Pahunga Lodu and Masu-Karera.

Return to Top

Sumba under Suharto’s New Order – 1965 to 1996

By the mid-1960s Indonesia was ranked as the poorest country in Asia with around 60% of its population living in poverty. It was also suffering from an economic crisis with hyper-inflation and falling demand. To make matters worse, Sukarno faced a communist uprising on Java and earlier in 1963 had committed his forces to invade British Borneo, which the UK had decided to incorporate into the Federation of Malaysia. It was now immersed in a guerrilla war with the UK, Australia and New Zealand.

On 30 September 1965 an abortive left-wing military coup in Jakarta ignited a violent anti-communist reaction. General Suharto, the head of Indonesia’s strategic command, quickly responded and crushed the coup within a few days. During October the army launched a purge of Indonesian communists and leftists, which eventually resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths. Despite widespread poverty, support for the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) on Sumba was minimal. Elsewhere PKI supporters were often found among the Christian clergy, but on Sumba the GKS recorded none of its pastors as being PKI members. They were more involved in local development projects such as providng clean drinking water or the training of farmers. Nevertheless some PKI members were arrested in Waingapu and Waikabubak and under the orders of the local military some, perhaps around 100, were killed (Webb 1986, 107). Most were assumed to be guilty on the basis of little evidence. Webb describes an incident where a local Sumbanese judge rounded up suspects and sent them through neighbouring villages in a truck, encouraging local villagers to physically assault them. The event was criticised by two local Dutch priests.

Within six months Suharto had toppled the Sukarno government, and on 12 March 1966 took effective control of the country. One year later he was appointed acting president. The top priorities of Suharto’s authoritarian military-led coalition were the elimination of the communist party, the restoration of stability and the revival of the economy - an approach that it promoted as the New Order. Politically Suharto aligned himself with the anti-communist, pro-military Golkar party, which had only just been formed in 1964. As authority became increasingly centralised, Golkar soon began to dominate party politics throughout the archipelago, including Sumba.

To promote its anti-communist drive, the Suharto regime exploited religion, emphasising the Pancasila principle of ‘Belief in One Almighty God’. Henceforth all Indonesian citizens were obliged to belong to one of the six officially recognised religions, the identity of which had to be recorded in their Kartu Tanda Penduduk (resident identity card). Those who had no religion were forced to claim one, or risk prosecution as a communist sympathiser. On Sumba this law was exploited by the GKS, who falsely linked the indigenous marapu religion to communism. Many Sumbanese listed themselves as Christians, primarily Protestants – Christianity officially quadrupled between 1955 and 1978 and by 1986 had increased tenfold (Lundry 2020). Yet many still retained their underlying marapu beliefs.

Umbu Haramburu Kapita, the bupati of East Sumba from 1967 to 1978

Archive Department of Nusa Tenggara Timur

In 1971 the first elections were held under the New Order. While Golkar won 63% of the vote nationally, on Sumba, Parkindo (the Indonesian Christian Party) defeated Golkar in both East and West Sumba, leaving Golkar as the runner up (Evans 2003, 48). In East Sumba Parkindo received 49.3% of the vote and in West Sumba 39.3% (Hering and Willis 1973, 39). Thereafter, support for Golkar increased as local politicians realised that it was the only party that offered a route up the political ladder along with access to Kupang and Jakarta. Over the following years Golkar successfully obtained subsidies for Sumba from central government and money for development.

In 1967 the GKS had established a Christian Agricultural Training Centre in Lewa, which included an agricultural machinery repair shop. It was supported by two Dutch engineers sent there by the Reformed Church mission. A national school building programme began in 1973, increasing the number of elementary schools (especially in rural areas), and establishing more secondary schools. Investments followed in regional clinics, power plants and electricity lines, in agricultural and irrigation projects as well as dams. In 1980 the decision was made to build two hospitals, one in Waingapu and the other in Waikabubak. In 1988 Suharto commissioned a major project to construct 904km of roads on the island (News on Indonesia, May-June 1988). By now there were several flights each week between Waingapu and Kupang.

On 19 August 1977 Sumba was rocked by a major earthquake measuring 8.3 on the Richter scale. It originated under the seabed on the south side of Sumba Island and triggered a tsunami, which was propagated toward the south coasts of Sumba, Sumbawa, Lombok and Bali. Sumbawa was the worst affected, with 68 deaths recorded.

Under Suharto, Indonesian poverty fell from 45% in 1970 to 11% in 1996, life expectancy rose from 47 years in 1966 to 67 in 1997, and infant mortality was cut by 60% (Lindsey 2021). By 1983 primary school enrolment nationally had risen to 90% and the education gap between boys and girls almost closed. On Sumba there was a significant rise in prosperity and many people quickly realised that voting for Golkar led to development. On the other hand, government employees were intimidated to vote for Golkar, risking dismissal if they refused to comply.

In 1993 Suharto came under fire from Megawati, a daughter of Sukarno and the recently chosen leader of the PDI Party. She demanded reformasi – political and economic reform. When Suharto attempted to have her deposed, students in Medan began a protest that quickly spread to Jakarta. Megawati remained a fierce critic but in 1996, Suharto finally engineered her removal from the PDI and banned her for running for president, leading to further rioting in Jakarta. Nevertheless, widespread demands for reformasi continued.

In 1994 Lukas Mbili Kaborang, a Sumbanese civil servant from Karera who had been working in Kupang for around 30 years, was elected bupati of East Sumba, just defeating his opponent, Umbu Mehang Kunda. In 1995 East Sumba was affected by a severe drought that resulted in major food shortages in 33 out of the 101 desa in the regency, especially those located in Pahunga Lodu (News and Views Indonesia 1996, 11). The government in Kupang responded by sending supplies of rice and other foods.

Return to Top

Sumba Post-Suharto – 1996 to 2023

Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and in 1998 its GDP declined by 15%. As capital flooded out of the country, the rupiah lost over 80% of its value and inflation soared with fuel prices rising by 70%. In May mass riots broke out in the main cities of Java and Sumatra, inflamed by police killings. To make matters worse, on Sumba the rains failed during the winter of 1997-98 devastating two maize harvests (Vel 151). It then rained in the middle of the dry season, harming the vegetable crops.

On 21 May 1998 back in Jakarta, Suharto was finally persuaded to resign and Vice President B. J. Habibie took over the presidency.

On Sumba and throughout the rest of eastern Indonesia there had been no mass movement for reformasi, although people were well aware of the situation on Java. The Sumbanese and their leaders had prospered significantly under the Suharto regime. However the reformasi banner was exploited in West Sumba to unseat its Golkar-sponsored bupati, a man from Wewewa who had been accused of corruption and nepotism. On 29 October 1998 several hundred demonstrators gathered in front of the regency office in Waikabubak demanding the resignation of bupati Rudolf Malo (Kuipers 2015). Over the following week the protests grew in size and intensity.

A grainy photo of protests in West Sumba against the bupati and KKN (corruption, collusion and nepotism), November 1998. Copyright Pos Kupang.

On 5 November 1998 men from Wewewa who were supporters of the bupati travelled to Waikabubak and clashed with Loli residents. Fighting began, during which 19 people were killed and hundreds of houses were incinerated. The incident went down as Kamis Berdarah, Bloody Thursday.

In Jakarta the new Habibie government moved swiftly to introduce reforms, the first being the Regional Autonomy Law number 22, passed in May 1999, which aimed to transform the country from a centralised autocracy to a decentralised democracy. It provided regencies (kabupaten) and municipalities (kota) with the power to regulate their affairs with the consent of their provincial governor. Many responded by changing their borders or splitting into more rational communities. Thus in West Sumba the six kecamatan were divided into fifteen smaller kecamatan, while in East Sumba in 2000 six new kecamatan were created: Kahaungu Eti, Karera, Matawai La Pawu, Nggaha Ori Angu, Pinu Pahar and Wulla Waijelu. By 2002 East Sumba had 15 kecamatan, 123 desa and 16 kelurahans.

The first free democratic elections were held in June 1999 although provincial governors, mayors and bupatis were still selected by their respective representative councils. Nationally Megawati’s PDI-P party (Indonesian Party in Struggle) trounced Golkar, with Abdurrahman Wahid elected President and Megawati Vice President. Yet in NTT Golkar maintained its popularity, despite the downfall of Suharto. In East Sumba the Golkar candidate, Umbu Mehang Kunda, a nobleman from Rindi, succeeded Lukas Mbili Kaborang as the bupati by a one vote margin. However in West Sumba, the popular Waingapu-born academic Manasse Malo, the founder of the PDKB party (Partai Demokrasi Kasih Bangsa), trounced Golkar.

Following the elections, pressure was applied to bupati Umbu Mehang Kunda and his government in East Sumba to divide their kabupaten into two. Umbu Mehang Kunda strongly resisted and maintained the unity of the regency.

Umbu Mehang Kunda, bupati of East Sumba from 2000 to 2008

Archive Department of Nusa Tenggara Timur

In 2004 the regional government electoral law was amended so that provincial governors, district bupati and the mayors of towns and cities would henceforth be democratically elected by the people. In the June 2005 elections the citizens of Sumba were able to elect their own leaders for the first time in their history. In East Sumba the incumbent Golkar candidate, Umbu Mehang Kunda, won just ahead of his main adversary, Lukas Mbadi Kaborang (Vel 2001, 105). In West Sumba the Golkar candidate Julianus Pote Leba, a medical doctor, was elected bupati.

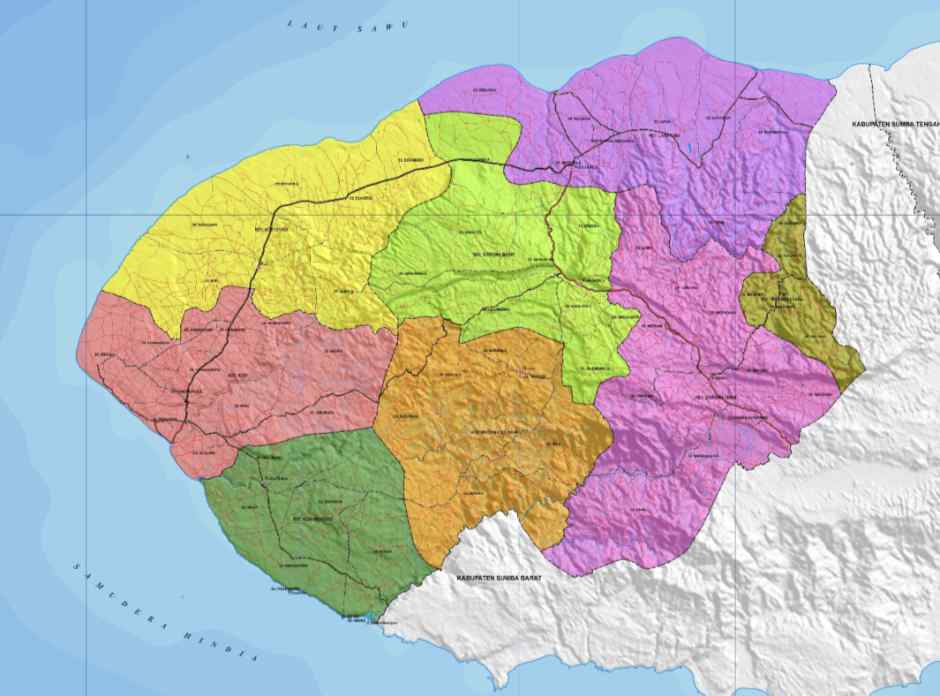

However on 2 January 2007 the West Sumba Regency was split into three along ethnic lines to create Sumba Barat Daya (Southwest Sumba) and Sumba Tengah (Central Sumba), leaving Sumba Barat much reduced in size. Sumba Barat Daya had 8 kecamatan: Kodi, Kodi Bangedo, Kodi Utara, Laura, Wewewa Barat, Wewewa Selatan, Wewewa Timur and Wewewa Utara. Sumba Tengah had 4 kecamatan: Katikutana, Mamboro, Umbu Ratu Nggay and Umbu Ratu Nggay Bartat. The smaller Sumba Barat was left with 6 kecamatan: Lamboya, Lamboya Barat, Loli, Kota Waikabubak, Tana Righu and Wanukaka.

Prior to 2007 East Sumba had 17 kecamatan: Haharu, Kahaungu Eti, Kambata Mapambuhang, Kambera, Karera, Kota Waingapu, Lewa, Matawai La Pawu, Nggaha Ori Angu, Paberiwai, Pahunga Lodu, Pandawai, Pinu Pahar, Rindi, Tabundung, Umalulu and Wula Waijelu. However in 2007 five new kecamatan were created: Kanatang, Katala Hamu Lingu, Lewa Tidahu, Mahu and Ngadu Ngala.

The increasing number of regencies and bupatis also increased the likelihood of corruption. In May 2014 we were eating in a restaurant in Waingapu when we were suddenly joined by a large police SWAT team wearing helmets and body armour, machineguns tightly strapped to their chests. They had just arrived from Waikabubak where they had been sent from Kupang to ensure there were no outbreaks of violence following the arrest of the bupati of Sumba Barat, Jubilate Pieter Pandango. The Chief Prosecutor of Nusa Tenggara Timur had issued a warrant for his alleged embezzlement of Rp 186 million ($14,120) from the district budget regarding the procurement of 158 motorbikes in 2011 worth Rp 3.2 billion. He was incarcerated in Kupang prison but suspiciously released in 2015 because of ill-health.

In 2013 the runway at Waingapu airport was extended.

In recent years Sumba has suffered from a combination of climate change and natural disasters, with major droughts occurring in 2016 and 2019. In 2019 East Sumba experienced 249 days in a row without rain, resulting in major crop failures and the deaths of livestock and horses (Jakarta Post). In the same year there was an outbreak of African swine fever that devastated the pig population. In April 2021 the island was struck by Cyclone Seroja that washed away crops and flooded riverside villages. The high water broke the dam at Kambaniru close to Waingapu, destroying 1,440 hectares of rice paddies. Most recently in early 2023 the crops of East Sumba farmers were devastated by a plague of locusts.

Since 2007 the process of decentralisation has continued and several more kecamatan have been created. Today Sumba is divided into 44 kecamatan, 22 in West Sumba and 22 in East Sumba:

- Sumba Barat Daya (Southwest Sumba) has 11 kecamatan and 173 desa:

- Sumba Tengah (Central Sumba) has 5 kecamatan and 65 desa:

- Sumba Barat (West Sumba) has 6 kecamatan and 74 desa:

- Sumba Timur (East Sumba) has 22 kecamatan and 140 desa:

The Kabupaten of Sumba and their Kecamatan

| Sumba Barat Daya | Sumba Tengah | Sumba Barat | Sumba Timur |

| Kodi Bangedo | Katiku Tana | Kota Waikabubak | Haharu |

| Kodi Balaghar | Katiku Tana Selatan | Lamboya | Kahaungu Eti |

| Kodi | Mamboro | Lamboya Barat | Kambata Mapambuhang |

| Kodi Utara | Umbu Ratu Nggay | Laratama | Kambera |

| Kota Tambolaka | Umbu Ratu Nggay Barat | Loli | Kanatang |

| Laura | Wanukaka | Karera | |

| Wewewa Barat | Katala Hamu Lingu | ||

| Wewewa Selatan | Kota Waingapu | ||

| Wewewa Tengah | Lewa | ||

| Wewewa Timur | Lewa Tidahu | ||

| Wewewa Utara | Mahu | ||

| Matawai La Pawu | |||

| Ngadu Ngala | |||

| Nggaha Ori Angu | |||

| Paberiwai | |||

| Pahunga Lodu | |||

| Pandawai | |||

| Pinu Pahar | |||

| Rindi | |||

| Tabundung | |||

| Umalulu | |||

| Wula Waijelu |

Above: the 8 kecamatan of Sumba Barat Daya

Below: the 5 kecamatan of Sumba Tengah

Above: The 6 kecamatan of West Sumba

Below: The 22 kecamatan of East Sumba

Return to Top

Bibliography

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1969. System and Meaning in East Sumba Textile Design: A Study in Traditional Indonesian Art, Cultural Report Series 16, Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Adams, Ron, 2004. The Megalithic Tradition of West Sumba, Unpublished.

Adams, Ronald Lynn, 2007. The Megalithic Tradition of West Sumba, Indonesia: An Ethnoanthropological Investigation of Megalith Construction, Doctoral Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, 2007.

Adams, Ron L., 2007. Transforming Stone: Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives on Megalith Form in Eastern Indonesia, Megalithic Quarrying: Sourcing, Extracting and Manipulating the Stones, Proceedings of the XV UISPP World Congress (Lisbon, 4-9 September 2006), Archaeopress, Oxford.

Adams, Ron L., 2010. Megalithic Tombs, Power, and Social relations in West Sumba, Indonesia, Monumental Questions: Prehistoric Megaliths, Mounds, and Enclosures, Proceedings of the XV UISPP World Congress (Lisbon, 4-9 September 2006), pp. 279-284, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Adams, Ron L., 2016. Big Animals and Big Stones: An Ethnoarchaeological Exploration of the Social Dynamics of Livestock Use in Megalithic Societies of Eastern Indonesia, Mégalithismes vivants et passés: approches croisées, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Anon., 1978. Sejarah Kebangkitan Nasional Daerah Nusa Tenggara Timur, Proyek Penelitian dan Pencatatan Kebudayaan Daerah, Jakarta.

Bagus Wirawan, A. A., 2008. Respons Lokal Terhadap Revolusi Indonesia di Sunda Kecil, 1945 – 1950, Humaniora, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 51-62.

Bulbeck, David, 2017. Traditions of Jars as Mortuary Containers in the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago, New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory, pp. 141-164, ANU Press.

Callaway, Ewen, 2016. Human remains found in hobbit cave, Nature News, 21 September 2016, https://www.nature.com/news/human-remains-found-in-hobbit-cave-1.20656

Chauvel, Richard, 2008. Nationalists, Soldiers and Separatists: The Ambonese Islands from Colonialism to Revolt, 1880-1950, Brill, Leiden.

Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; et al 2017. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago, Nature, vo. 547, pp. 306-310.

Couvreur, A., 1917. Aard en wezen der inlandsche zelfbesturen op het eiland Soemba, Tijdschrift voor het binnenlandsch bestuur, vol. 53, issue 4, pp. 206-219.

Cox, Murray P., Hudjashov, Georgi, Sim, Andre, et al, 2016. Small Traditional Human Communities Sustain Genomic Diversity over Microgeographic Scales despite Linguistic Isolation, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 33, issue 9, pp. 2273–2284.

Erasmus, Hans, and Leupe, Pieter Arend, 1879. Het eiland Soemba in 1759, Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde, vol. 27, issue 1, pp. 224-231.

Farram, Steven, 2004. From ‘Timor Koepang’ to ‘Timor NTT’: a Political History of West Timor, 1901-1967, doctoral thesis, Charles Darwin University, Darwin.

Farram, Steven, 2007. Jacobus Arnoldus Hazaart and the British interregnum in Netherlands Timor, 1812-1816, Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde, vol. 163, issue 4, pp. 455-475.

Feddersen, Carl Fredrik, 2017. Principled Pragmatism VOC Interaction with Makassar 1637-68, and the Nature of Company Diplomacy, Cappelen Damm Akademisk

Forth, Gregory L., 1981. Rindi: an Ethnographic Study of a Traditional Domain in Eastern Sumba, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Galipaud, Jean-Christophe, Kinaston, Rebecca; Halcrow, Sian; et al, 2016. The Pain Haka burial ground on Flores: Indonesian evidence for a shared Neolithic belief system in Southeast Asia, Antiquity, vol. 90, issue 354, pp. 1505-1521.

Gde Agung, Ide Anak Agung, 1996. From the Formation of the State of East Indonesia Towards the Establishment of the United States of Indonesia, Yayasan Obor Indonesia, Jakarta.

Gronovius, D. J. van den Dungen, 1855. Beschrijving van het eiland Soemba of Sandelhout, Tijdschrift voor Neerlands Indië, 17th year, vol. 1, pp. 277-312.

Gunn, Geoffrey C., 2016. The Timor-Macao Sandalwood Trade and the Asian Discovery of the Great South Land?, Review of Culture, vol. 53, pp. 125-148.

Hangelbroek, Hendrik, 1910. Soemba: land en volk, G. F. Hummelen, Assen.

Hägerdal, Hans, 2018. Held's History of Sumbawa: an Annotated Translation, Amsterdam University Press.

Heereken, H. R. van, 1956. The Urn Cemetery at Melolo, East Sumba (Indonesia), Berita Dinas Purbakala (Bulletin of the Archaeological Service of the Republic of Indonesia), No. 3, Jakarta.

Heereken, H. R. van, 1958. The Bronze-Iron Age of Indonesia, Martinus Nijhoff, The Haague.

Heynen, F. C., 1876. Schetsen uit de Nederlandsch-Indische missie: de kerkelijke statien op Flores, Bogaerts, ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

Hoskins, Janet, 1996. The Heritage of Headhunting: History, Ideology and Violence on Sumba 1890-1990, Headhunting and the Social Imagination in Southeast Asia, pp. 216-248, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Hoskins, Janet, 1997. The Play of Time: Kodi Perspectives on Calendars, History, and Exchange, University of California Press.

Hoskins, Janet, 1998. Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People's Lives, Routledge, New York.

Hoskins, Janet, 2004. Slaves, brides and other ‘gifts’: resistance, marriage and rank in Eastern Indonesia, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, vol. 25, issue 2, pp. 1-18.

Jatmiko, 2006. Discovery of Palaeolithic Tools in Flores, Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective: R.P. Soejono's Festschrift, pp. 162-173, Yayasan Obor Indonesia

Jatmiko, 2017. Jejak Budaya Awangbangkal Terkuak di Pulau Sirang, Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional,

Kahin, George McT., 1949. Indirect Rule in East Indonesia, Pacific Affairs, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 227-238.

Kapita, Umbu Hina, 1976a. Masyarakat Sumba dan adat istiadatnya, Panitia Penerbit Naskah-Naskah Kebudayaan Daerah Sumba, Dewan Penata Layanan Gereja Kristen Sumba, Waingapu.

Kapita, Umbu Hina, 1976b. Sumba di dalam jangkauan jaman, Panitia Penerbit Naskah-Naskah Kebudayaan Daerah Sumba, Dewan Penata Layanan Gereja Kristen Sumba, Waingapu.

Keane, E.W. 1990. The social life of representations: ritual speech and exchange in Anakalang (Sumba, Eastern Indonesia), Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago.

Kleiweg de Zwaan, J. P., 1941. Oude urn-schedels van Melolo (Oost Soemba), T.A.G.' 58, pp. 342-362.

Kruseman, J. D, 1835. Beschrijving van het Sandelhout Eiland, De Oosterling, Tijdschrift bij uitsluiting toegewigd an de verbreiding der kennis van Oost-Indië, vol. 2, pp. 63-86, K. van Hulst.

Kruyt, Albertus Christiaan, 1922. De Soembaneezen, Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden.

Lancing, J. Stephen, Cox, Murray P., Downey, Sean S., et al, 2007. Coevolution of languages and genes on the island of Sumba, eastern Indonesia, PNAS, vo. 104, no. 41.

Needham, Rodney, 1980. Principles and Variations in the Structure of Sumbanese Society, in The Flow of Life: Essays on Eastern Indonesia, James J. Fox (ed.), pp. 21–47, Cambridge.

Needham, Rodney, 1983. Sumba and the Slave Trade, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, Melbourne.

Needham, Rodney, 1987. Mamboru: history and structure in a domain in northwestern Sumba, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Newitt, Malyan, 2004. A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400-1668, Routledge.

Pos, W. 1901. Sumbaneesche woordenlijst, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volken- kunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, 58, pp.184–284.

Ptak, Roderich, 1999. China's Seaborne Trade with South and Southeast Asia, 1200-1750, Ashgate.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. de, 1890. Eenige Mededeelingen over Soemba, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIII, pp. 565-595.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. de, 1891. Soembaneesch-Hollandsche woordenlijst met een schets eener grammatika, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIV, pp. 234-282.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. de, 1906. Historische aanteekeningen over Soemba, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 48, pp.185-316.

Roos, S., 1872. Bijdrage tot de kennis van taal, land en volk op het eiland Sumba, Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, vol. 36, pp. 1-125.

Rouffaer, Gerrit Pieter, 1910. Photographic archive.

Snell, Christiaan Alfred Raoul Diederik, 1948. Human Skulls from the Urn-field of Melolo, East-Sumba, Acta Neerlandica Morphologiae Normalis Et Pathologicae, vol. 6, A. Oosthoek, Utrecht.

Steiner, H. Arthur, 1947. Post-War Government of the Netherlands East Indies, The Journal of Politics, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 624-652.

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay, 2012. The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History, John Wiley & Sons.

Thomaz, Luis Filipe F. R., 1995. The image of the Archipelago in Portuguese cartography of the 16th and early 17th centuries, Archipel, vol. 49, pp. 79-124.

Van Alphen, J. J., 2009. Ethnographic Notes on Sumba, The Indonesia Reader, pp. 211–213, Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Vermast, Alfons M., 1895. Remonte-Aankoop op het eiland Sopemba (Sandelhout Eiland) in 1888, H. M. van Dorp, Batavia.

Vorderman, A. G., 1888. Het Journaal van Albert Colfs, eene Bijdrage tot de Kennis Kleine Soenda-Eilanden, Batavia.

Webb, R.A.F. Paul, 1986. The Sickle and the Cross: Christian and Communist in Bali, Flores, Sumba and Timor, 1965–1967, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 17, pp. 94-112.

Wellem, Frederiek Djara, 2004. Injil dan marapu: suatu studi historis-teologis tentang perjumpaan Injil dengan masyarakat Sumba pada periode 1876-1990, BPK Gunung Mulia, Jakarta.

Widianto, Harry, 2006. Austronesian Prehistory from the Perspective of Skeletal Anthropology, Austronesian Diaspora and the Ethnogeneses of People in Indonesian Archipelago, Proceedings of the International Symposium, pp. 172-185, Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Wielenga, D.K., 1908. Soemba: Op reis (van Pajeti naar Memboro), De Macedonièr, vol. 12, pp. 167-74, 257-69.

Wielenga, D.K., 1911. Reizen op Soemba, De Macedonièr, vol. 15, pp. 303-308, 328-334 (166-172?)

Wielenga, D.K., 1912. Reizen op West-Soemba (IV), De Macedonièr, vol. 16, pp. 169-174.

Wielenga, D.K., 1928. Oemboe Dongga, het kampong-hoofd op Soemba: verhaal uit het leven van een heiden. 180p. Ill. Kampen: Kok, 1928.

Wielenga, D.K., 1933. Merkwaardig denken: schetsen uit de Soembaneesche gedachtenwereld. 253p. Ill. Kampen: Kok, 1933.

Wielenga, J. D., 1935. Weerzien op Soemba: fragmenten uit een dagboek, Bosch & Keuning, Baarn.

Willams, Wilhelmus Johan Antonius, 1940. De necropool van Melolo (Oost-Soemba), Notulen Bataviaasch Genootschap, vol. 68.

Wijngaarden, J. K., 1893. Naar Soemba, Mededeelingen van wege het Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap, vol. 37, pp. 352–76.

Witkamp, H., 1912. Een verkenningstocht over het eiland Soemba, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, tweede serie, vol. 29, pp. 744-75, Brill, Leiden.

Witkamp, H., 1913. Een verkenningstocht over het eiland Soemba, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, tweede serie, vol. 30, pp. 8-27, 484-505, and 619-37, Brill, Leiden.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 7 March 2023.