Asian Textile Studies

Contents

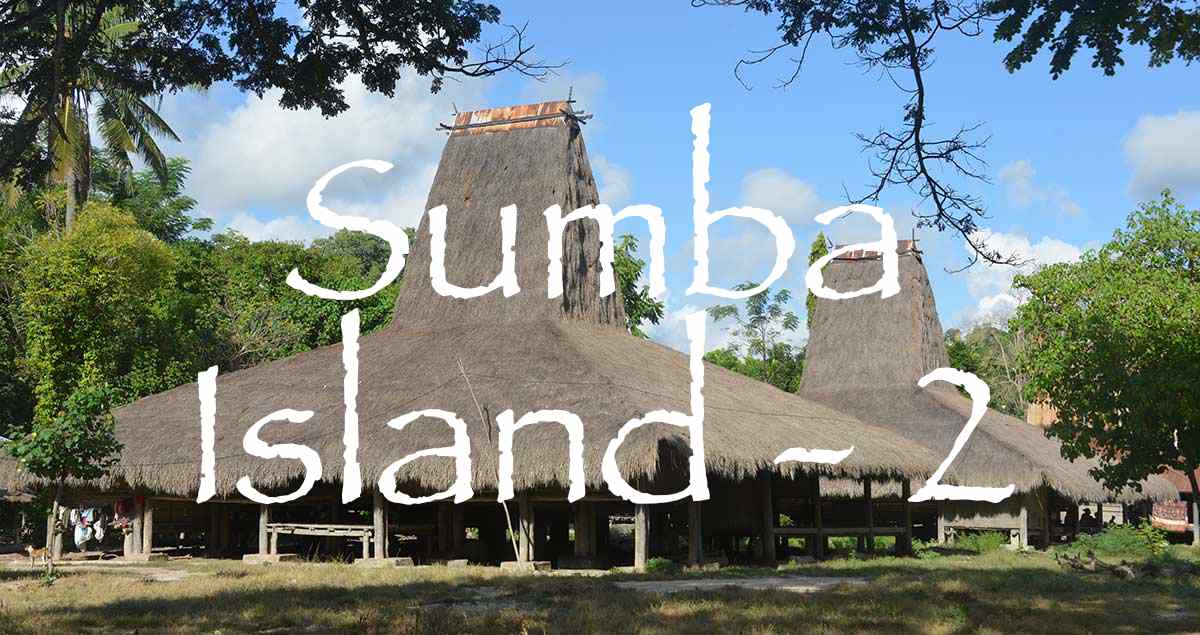

Sumba Part 2

Sumba from 1866 to 1890 – The Dutch Establish a Presence

The Visit of Herman ten Kate, 1891

The Visit of J. K. Wijngaarden, 1892

Dutch Attitudes Harden, 1891-1905

The Dutch Reformed Mission

Sumba from 1906 to 1942 – Under Dutch Colonial Rule

The Looming Threat of War

Return to Sumba Part 1

Go to Sumba Part 3

Sumba from 1866 to 1890 – The Dutch Establish a Presence

In August 1866 the Resident of Timur, Jan George Coorengel, finally installed the first Dutch controleur on Sumba. He was Samuel Roos, who had previously been the gezaghebber of Larantuka (Steenbrink 2002, 155). He was located at Kambaniru to the east of the new port of Waingapu and was assisted by H. van Heuckelum and a translator called Baliede who had not only lived on Sumba for some years and was well acquainted with some of the Rajas, but was also married to a daughter of the Raja of Mangili (Kapita 1976b, 155; Haripranata 1984, 66-67). He was protected by twelve armed policemen whose number was later reduced to two (Roos 1872, 3).

Despite being an agent of the Dutch government, Roos’s main role was not to rule,-but to advise and liaise with the regional Rajas while leaving them to govern their own domains. Yet he was not without authority – the colonial government could forcefully intervene whenever necessary.

His one additional role was to supress slave-trading. In 1860 the Dutch officially abolished slavery throughout the East Indies and in the very same year sank ten Endenese slave ships at Kapunduk on the northeast coast of East Sumba. Yet the slave trade continued, with Sumbanese leaders profitably supplying slaves to local Endenese merchants, many of whom resided on the north coast of Sumba. The Dutch were particularly concerned about the activities of the Arabic horse merchant Syarif Abdur Rahman al-Gadri, who had found that the slave trade was more profitable than the horse trade and was even encouraging internal warfare to generate captives (Kapita 1976b, 28).

Roos remained on Sumba for 3½ years, departing in 1873. While there, he travelled extensively and documented many aspects of Sumbanese life. The island was divided into many relatively small domains or negori, some significant such as Kambera with 254 houses and others with only 30 or 40 houses. They were each headed by a noble male hereditary chief, a supreme ruler holding power over the lives and property of all of his subjects (Roos 1872, 5). Against this background Roos and his officials proceeded cautiously and diplomatically, trying to build relationships with the local rulers and steering them in a more positive and cooperative direction. While Roos lacked the military support of a local garrison he could, in an emergency, request the dispatch from Kupang of 150 Savunese and Rotinese warriors armed with rifles (Roos 1972, 16).

Roos discovered that human life had very little value on Sumba. There was no other right on Sumba other than that of the strongest. Murder, robbery and the slave trade were commonplace. Slave ownership was widespread, especially by the nobility, and also by the wealthier commoners, the kabihu.

Keeping slaves is common on Sumba; the rich who own horses and other livestock also have slaves; without slaves they would not be called rich (Roos 1872, 10).

If a noble chief set off on a journey, he might be accompanied by 120 or more slaves, all on horseback. Domestic slaves were generally treated well and lived together with the rest of the family. They worked in the gardens of the nobility and tended their livestock, even participating in robbery and warfare.

At the same time, slaves were still being traded, especially by the Endenese, Mamboru being the main port from which they were exported (Roos 1872, 11). The price of an adult slave was 50 to 75 guilders or a horse, although that of an attractive young woman could be 125 guilders or two horses. Children were often sold to the Endenese for 5 to 6 Endenese textiles and sometimes, because of a lack of food, for 3 bags of rice. Some slaves were traded elsewhere on Sumba while others were transported to Ende Island off Flores, Bima on Sumbawa or Pidju on Lombok. Although the Dutch had outlawed slavery, on Sumba it was so deeply woven into the local culture that at that time its forcible abolition was unthinkable.

Human sacrifice was also still being practised. Roos had discovered that following the burial of the Raja of Kambera, seven households had been massacred including ten men from Mauliru (Roos 1872, 59). Thirty people had also been slaughtered on the occasion of the burial of the Raja of Melolo. The Rajas knew that the Dutch were opposed to such practices, so attempted to hide them from the officials.

Roos noted that a large part of Sumba was still sparsely populated. In the coastal areas, kampongs were located close to rivers, but in the interior they were mostly located in high, stony and difficult to reach places where women had to climb down several times a day to get water. Most kampongs were enclosed by wood and cactus fences and had only one or two entrances. There were no roads or bridges, only footpaths.

According to Kapita (1976a, 28):

During this period, all of Sumba was unsafe; villages that were formerly dispersed had to be brought together into a paraingu located on top of a hill, fortified by stones and sharp and thick [cactus] thorns. If a person went out of the village, he had to go with a group equipped with weapons, to the point that even to go and fetch water one had to be accompanied by an armed group.

By now the horse export business channelled through the new settlement of Waingapu and overseen by Syarif Abdur Rahman was proving highly profitable. For example, one Arab merchant bought 151 horses for Fl. 12,809 in May 1868 and exported them to Java for Fl. 34,000. In 1869 a total of 1,110 horses were exported through Waingapu.

Roos left Sumba on 24 April 1873 to take up an appointment as the assistant resident in Ternate. He was replaced by B. J. E. Roskott, the former controleur of Buru, who later that year reported on the island’s agricultural problems. Fertile land was scarce because most of the rivers flowed through narrow ravines making it impossible to use the water for irrigation. Furthermore, crops did not thrive on its infertile and dry soils, so there were shortages of cotton, tobacco and foodstuffs. To make matters worse, the regular theft of livestock coupled with constant disputes and local wars made agricultural development impossible. Only the strongest reigned.

In 1875 the office of the controleur was moved from Kambaniru to the small trading post of Waingapu with its important harbour. In 1877 the Dutch authorities finally arrested Syarif Abdur Rahman because of his involvement in the local slave trade. He was sent back to Kupang to account for his activities and died a few months later (Kapita 1976b, 38). That same year Protestant ministers were installed in Kambaniru and Melolo, the latter settlement benefiting from one of the first schools (Kapita 1976b, 62).

The lack of agricultural development was reinforced by a later report in 1878, which noted that the soils were composed of lime and sand and were difficult to fertilise, given that buffalo were almost non-existent. The people were backward and uneducated so the construction of irrigation systems was not a solution. Murder was a daily habit and there was no respect for property (Wellem 2004, 25). Roos had already noted that famine sometimes occurred on the island (Roos 1877, 494). Much cassava was grown on Ende Island and some of this was exported to Sumba (Roos 1877, 509).

Meanwhile the slave trade continued unabated. It has been estimated that at least 500 slaves were exported annually from Sumba to Ende Island, for onward trans-shipment to other parts of the archipelago (Needham 1983, 30). In September 1876, in an attempt to stem the flow, the Dutch stationed an armed vessel in Ende waters. Yet the following month a prauw sailed from Waingapu to Lombok carrying 27 male and female slaves (Wielenga 1918, 274).

The 1878 report confirmed that large-scale kidnapping and slave-trading continued to thrive on Sumba, as well as on Flores, Solor and Alor. To increase its presence on Sumba, during 1879 the Dutch East Indies government divided the island into two parts or onderafdeeling. They placed J. F. Th. Sickas a posthouder in Melolo, the capital of East Sumba and N. M. Ehrich was given the same position in Mamboro, then the capital of West Sumba. On 2 March 1880, J. H. H. Dornseiff was installed in Waingapu as controleur of Sumba, but he soon discovered the difficulties of dealing with such an unruly island.

In November 1880 following a dispute between Umbu Taralandu, the Raja of Lewa, and a Buginese trader in Waingapu, the Raja’s nephew Umbu Bidi Tau arrived in Waingapu with many armed escorts. They encircled and attacked the house of the controleur, who then fled to safety in Kupang (Kapita 1976b, 36; Steenbrink 2002, 155). The incident highlighted the vulnerability of isolated government representatives who lacked any local military support.

Elsewhere on the island the Raja of Napu, supported by the Endenese, was now at war with the district of Rakawatu to his south; the Raja of Kapunduk was fighting the Rajas of Bolobokat and Rawambau; the Raja of Lea was fighting with the Rajas of Taimanu, Kapunduk, Melolo and Tabundung; while the Raja of Rindi was fighting the Rajas of Mangili and Karera (Wellum 2004, 25).

In June 1881 controleur Dornseiff was succeeded by A. Mellink, who arrived along with the first Protestant missionary, J. J. van Alphen, a representative of the Nederlandsche Gereformeerde Zendings Vereenniging (NGZV). Van Alphen based himself in Melolo and, although his initial stay was short-lived (he left for Java in 1883 but returned later) he painted a rather black picture of the situation in Sumba the following year. He described the situation on the island as total anarchy. The nobles with the largest number of slaves were the most powerful, travelling to distant villages to steal from the inhabitants and even carry away girls and small children. There was no education and no law – the mighty could steal and plunder as they pleased, but the poor were punished for the same crimes with the loss of property or death.

In May 1882 the Resident of Kupang naively announced a reward of five hundred ringgits to anyone who could arrest and hand over the troublesome Raja of Lewa-Kambera and his nephew Umbu Bidi Tau. There was no response. The Dutch stationed a detachment of soldiers in Waingapu in 1884 but it was a short-term measure and they were withdrawn from the island in 1886 (Kapita 1976b, 37). In the meantime, the Raja of Lewa-Kambera maintained his hostile stance towards the Dutch authorities, supported by his nephew Umbu Bidi Tau and the latter’s son (Kapita 1976b, 37).

In an attempt to reduce costs, in 1884 Kupang replaced the position of controleur with a lower-rank civiele gezaghebber (administrator) called J. de Roo van Alderwerelt. He was still based in Waingapu, which at that time was still mainly inhabited by Islamic Endenese along with some Arabs, Buginese and Chinese. The following year the missionary Leemker briefly visited Waingapu, Kambaniru and Melolo, and discovered that the Protestant ministers had so far failed to make any converts among the Sumbanese who remained deeply devoted pagans. Surprisingly the sons of the Raja of Melolo requested the presence of a clergyman, for the sole reason that they could attend a school.

In 1886, Umbu Taralandu sacked Lakoka with the help of Endenese slave merchants. Many men were killed, horses were stolen and women and children were shipped back to Ende Island as slaves (Doherty 1891, 151).

In 1887 the Cincinnati-born butterfly collector William Doherty arrived at Waingapu and travelled extensively inland across East Sumba, reaching the mountain forests of Tabundung. He reported that the most powerful rulers were those of Lewa (who also held Kambera by right of conquest) and Melolo, the son of the latter ruling Patawang. West of Lewa came Taimanu, Kapunduk, Palmedo, Mamboro and finally Laura (1891, 155). Accompanied by Roo van Alderwerelt, Doherty rode to Kawangu to visited Umbu Taralandu, the Raja of Lewa-Kambera. The Raja was described as an ugly old man, well over six feet tall and wearing nothing but a dirty waist-cloth, his skinny limbs uncovered. His elder brother, Umbu Diki Kama Pira Ndawa I, the former Raja of Lewa who had given up the throne many years earlier, was also living in Kawangu but was dying of cancer. Umbu Taralandu eventually died of old age in 1892 and was succeeded by his nephew, Umbu Bidi Tau.

Doherty commented on the dry landscape and on the distribution of the population:

The grass is burnt every May or June, and for some months later, the country is as black as a coal, but travelling is easier and is usually done at this season. In some places the soil is exceedingly rich, and the population dense, especially in Melolo and Laura; but the country is everywhere dreary, and is far from green even just after the rains. Nevertheless [in] this region, the north-east coast from Laura to Rindi, is the civilized part of the island, and the seat of all the larger states. The coast itself is generally uninhabited for several miles inland, owing to the depredations of the Endenese pirates (1891, 146).

He also experienced the delicate security situation, where villagers were highly suspicious of strangers:

On the coast, one can now ride from Waingapu to Melolo without receiving anything from the men he meets but polite salutations. In the interior, even in the middle of the Lewa dominions, I never met a native not belonging to the village where I was staying, but we both prepared for battle, and spear and revolver were held in readiness till we had exchanged betel. Twice I was within an ace of being speared, because I came on men suddenly in the forest. When two parties meet, they halt when yet a long way apart, dismount, and drive their spears deep into the earth as a sign of peace, then exchange a ‘cooey’ (the well-known Australian cry, much used in Sumba), and yell out a question or two. Then two men advance, one from each party, and exchange betel, after which the others come forward warily, keeping a good grip on spear and shield. In spite of the tyranny of the kings over their subjects, and their occasional ferocity to conquered enemies, centralized government of any kind is better than this constant distrust of one's neighbours (1891, 155).

On 28 February 1888 a military commission arrived at Waingapu from Surabaya with orders to procure 280 horses for the Department for War and to ship them to Java via Makassar (Vermast 1895). They set up their base camp in the recently deserted prison and began constructing bamboo stables to accommodate 90 horses. The local climate was poor due to foul air blowing in from the coral sea shore and some of the soldiers came down with fever.

In April 1888, not long after the commission’s arrival, gezaghebber de Roo van Alderwerelt was replaced by the cavalry officer Marinus Theodorus de Korte.

Return to Top

The Visit of Herman ten Kate, 1891

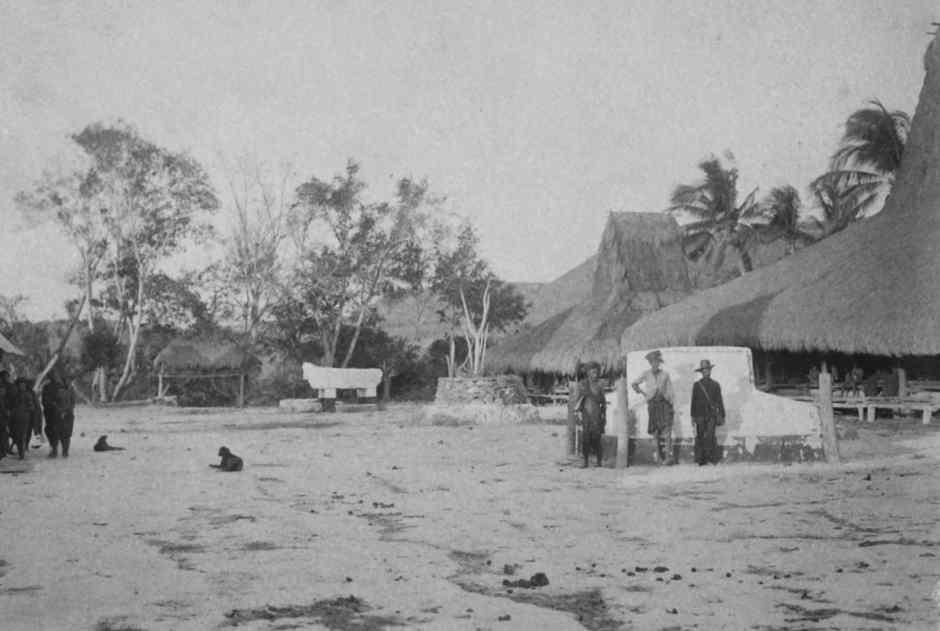

On 6 June 1891 the anthropologist Herman ten Kate arrived at Waingapu harbour aboard the Van Goens and was welcomed by gezaghebber M. Th. de Korte. He described Waingapu as the ugliest harbour town he had seen in the Timor Group – the ‘rubbish bin of Sumba’, a ramshackle mix of houses occupied by Endenese, Chinese and Arabs. The gezaghebber’s home was a primitive wood and bamboo dwelling situated at the far end of Waingapu – ‘entirely in proportion to the authority exercised by the Netherlands over Sumba’ (ten Kate 1894, 544).

He had arrived with the intention of spending 2½ months on the island but first visited Kambaniru, a Savunese village and the former base for the controleurs of Sumba, located about 4km east of the harbour on the Kambera River. It was now the home of the Protestant missionary J. J. van Alphen, who ten Kate was amazed could neither speak Sumbanese nor Savunese.

Ten Kate toured a significant part of the island on horseback and was primarily interested in its geology and natural history, although he did provide brief descriptions of some of the kampongs, most of which were composed of 10 houses or fewer. By contrast, the hill-top kampong of Waimbidi with its 20 houses was described as a fairly large kampong. Stakes on one side of the kampong held a few human skulls - evidence of ongoing headhunting. After attempting to buy a chicken, ten Kate concluded that almost everything on Sumba was expensive apart from human lives. Cold-blooded murders were ‘the order of the day on Sumba’ (ten Kate 1894, 561). Many days later, when ten Kate visited the Raja of Rindi, he observed fifteen human skulls standing on long stakes in the middle of the kampong, which consisted of twelve houses with buffalo-hide walls.

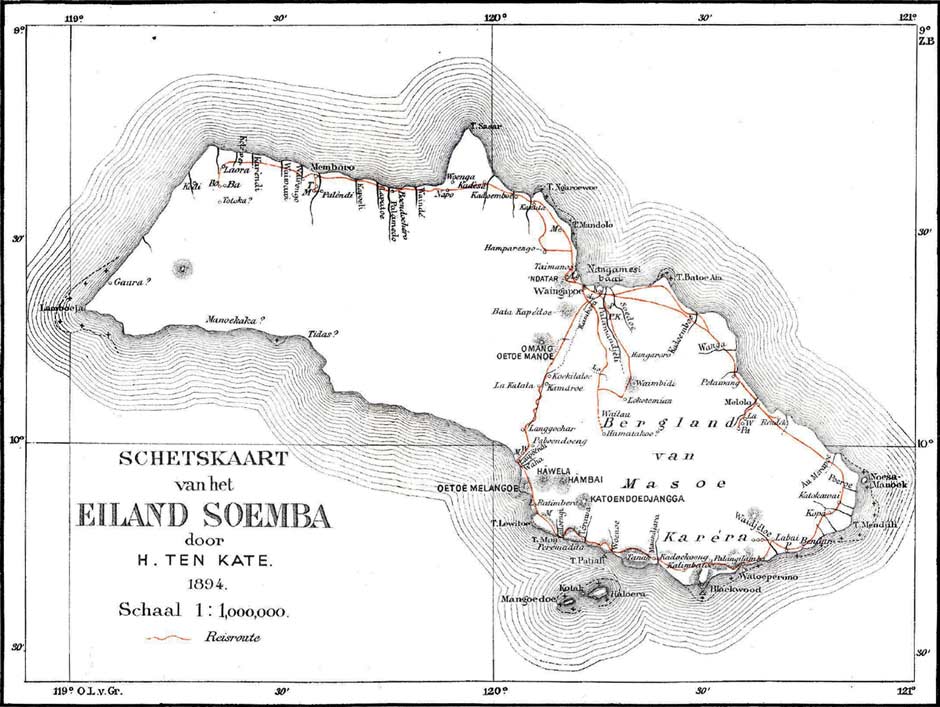

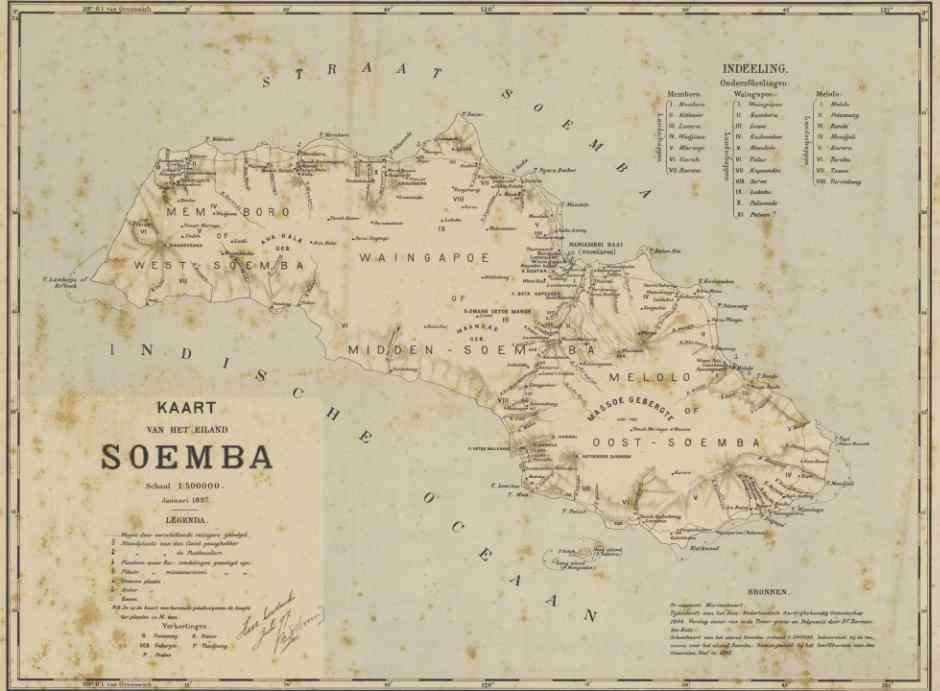

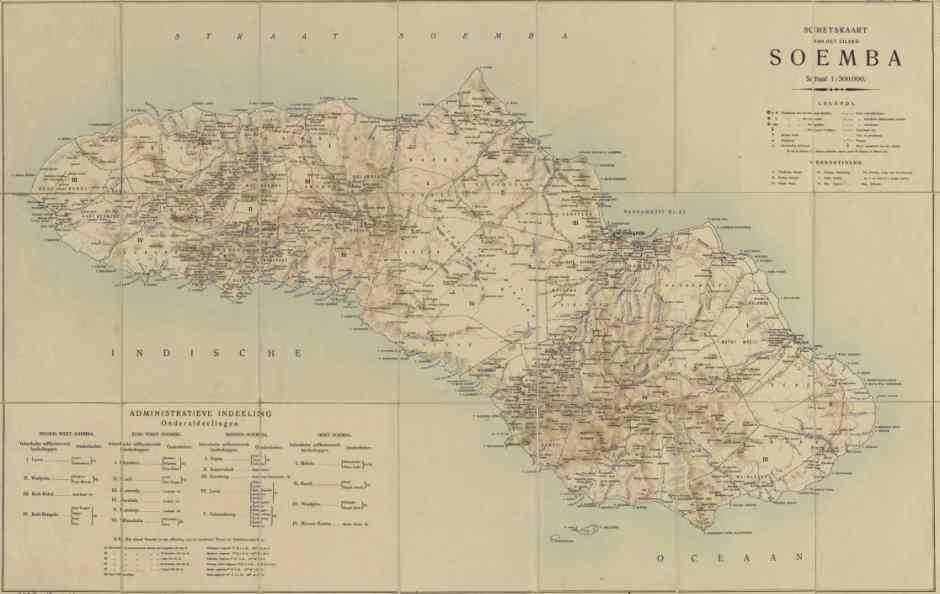

A sketch map of ten Kate's journey around Sumba Island in 1891

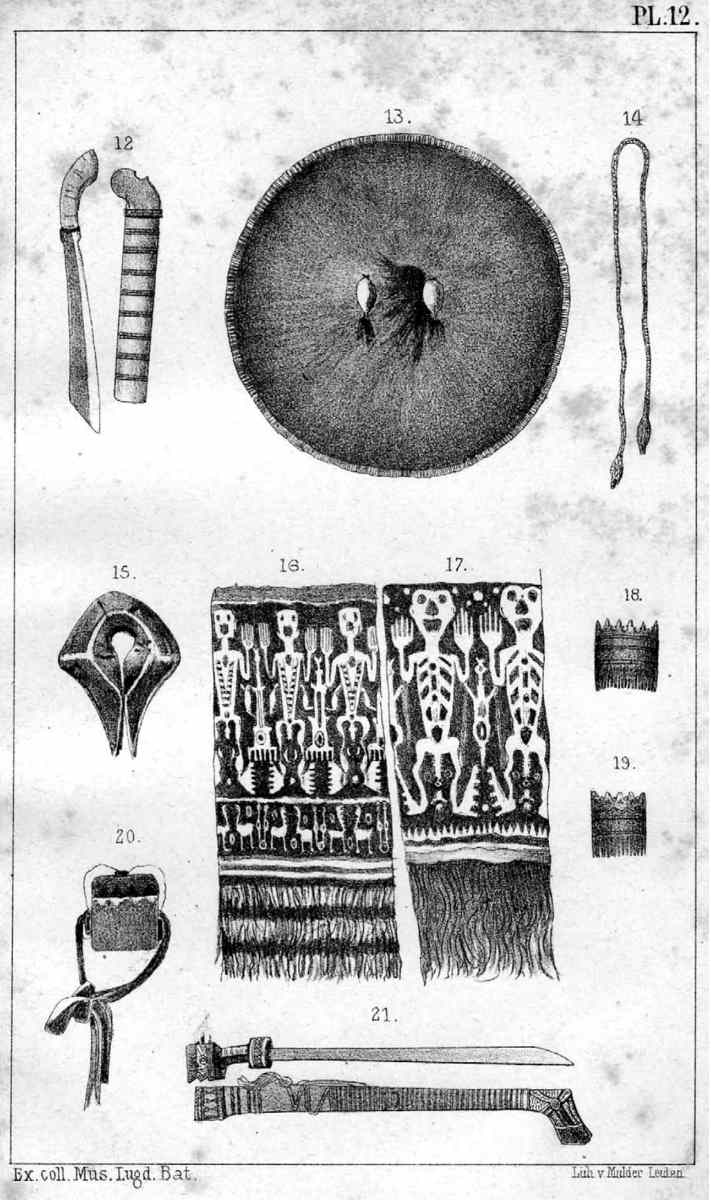

Some of the ethnographic material collected by ten Kate on Sumba

Return to Top

The Visit of J. K. Wijngaarden, 1892

In July 1892 the clergyman J. K. Wijngaarden sailed from Savu to Mangili, choosing the hazardous 30-hour crossing in a fully loaded local prauw rather than the far safer KPM steamship to Waingapu by way of Ende. As his prauw approached the shore it was prevented from sailing into the Puru River (Luka Burukulu) by the long offshore reef and for a while became temporarily stranded upon it before making landfall on the beach. He was immediately welcomed by the local missionary Willem Pos, who had been sent to Melolo by the Zending der Gereformeerde Kerke (Dutch Reformed Missionary Association).

The local region was thickly forested, which explained why some Savunese had previously come to Mangili to obtain wooden beams for constructing the church at Seba on Savu as well as the house for the Raja of Seba. Other Savunese even sailed their boats to Sumba to have them repaired. It was said that the two islands belonged together.

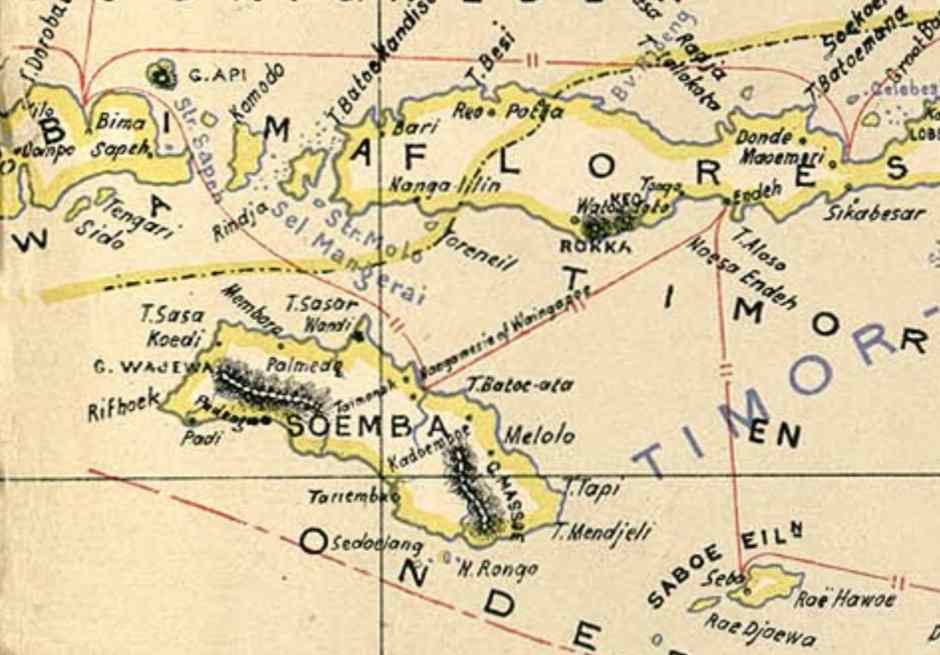

Sumba on the 1893 map of Nederlandsch-Indïe by H. Ph. Th. Witkamp, showing the steamship connections to Ende and Bima, J.H. de Bussy, Amsterdam

Because there was already such a significant Savunese population on Sumba, many Savunese came to Sumba temporarily every year for one to three months during the eastern monsoon, arriving in prauws fully loaded with 40 passengers (Wijngaarden 1893, 353-362). Many stayed on because of the ready supply of water and food and the cooler climate. Those who were sick often came to Sumba to recuperate. As Wijngaarden emphasised (1893, 368):

The Government would gladly see that there were more Sumba settlers, as a counterweight to the Endenese. The Savunese have a certain civilizing influence. Where they settle, the slave trade disappears. The Board promotes emigration as much as possible. Nevertheless, the move has not yet taken place on a large scale.

The Endenese were ‘a real disaster for Sumba’, taking over the island. They married Sumbanese women, adopted Sumbanese dress, followed local customs and spoke the local language. By such means ‘they conquer the land’.

Wijngaarden travelled on to Melolo, which was at that time a purely Savunese settlement with a population of 270. He was welcomed again by Willem Pos, who ran the local church and school, both attended by the local Savunese community. The school had 40 students and church attendance was good. Wijngaarden also noted that the first school had just opened in Waingapu (Wijngaarden 1893, 23).

Later Wijngaarden and Pos rode to Rindi to visit the Raja, a tall, stoutly built man who was bare-chested on their arrival, but later donned a dirty white jacket. The kampong of the Raja of Rindi consisted of a dozen houses arranged in the form of a street. Wijngaarden described the Raja as a cruel man who in the previous year had had 40 people killed:

.... one human life has no value for the Sumbanese. I heard tell that it takes more effort to slaughter a chicken than to kill a man.

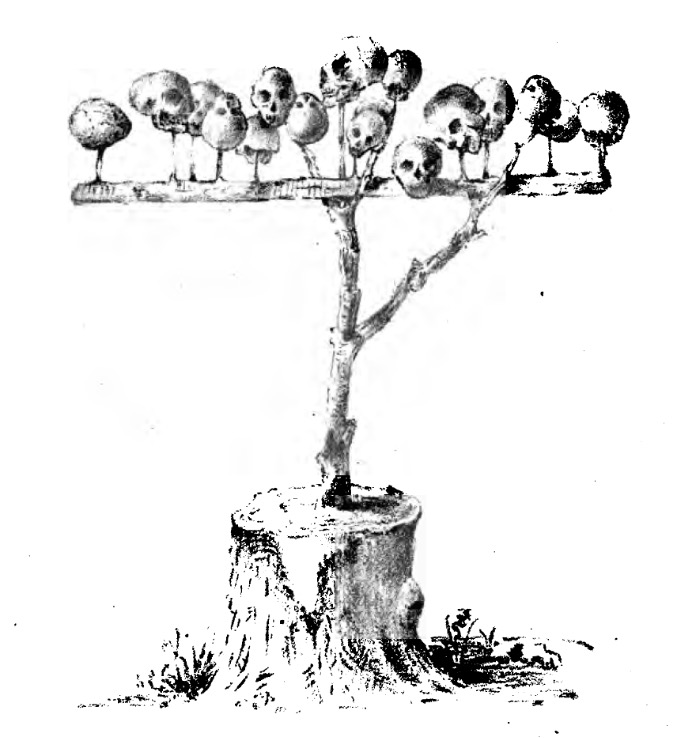

Evidence that head-hunting was still rife in Rindi can be gauged by his illustration of the skull tree located close to the Raja’s residence in Parai Yawang. The kampong was protected by a defensive stone wall and a hedge of cactus, making it difficult for an enemy to enter.

Human skulls on the skull tree by the house of the Raja of Rindi. From Wijngaarden 1893.

Return to Top

Dutch Attitudes Harden, 1891-1905

In the final decades of the nineteenth century the government of the Netherlands East Indies in Batavia began to seriously question the policy of ‘non-interference’ in the Outer Islands. This had been based on purely economic grounds, recognising that the administrative costs of direct control would far outweigh any profit that could have been gained from these unproductive islands. However local wars and insurrections were becoming widespread throughout the archipelago, and local government officials on the ground were becoming frustrated and humiliated at their inability to intervene. On Sumba for example, the controleur of Melolo had been embarrassingly forced to abandon his post after being driven away by local people (Farram 2004, 68).

Sketch map of Sumba Island published in 1895

Compiled by the office of the General Staff in 1892

Slowly but surely the Dutch were being sucked into direct intervention. Events were brought to a head in 1899. The Raja of Tabundung, Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu (aka Umbu Pindingara), had instructed two slaves to steal some livestock from Umbu Bidi Tau, the Raja of Lewa-Kambera, including his beloved horse. They were spotted and followed back to the village of Tanundangu, the home of the Raja of Tabundung. Umbu Bidi Tau and his sons responded by attacking Tanundangu, burning all the houses, looting its treasure and capturing a number of residents. Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu managed to escape from the royal enclosure but his wife was captured and later killed and his property was seized (Kapita 1976b, 40). On 15 August 1899, Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu’s warriors retaliated by burning down the village of Lambanapu to the south of Waingapu in the territory of Umbu Bidi Tau. Umbu Bidi Tau immediately gathered his warriors from Kambera and Kadumbulu, fearing that Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu would attack again. On the following day the two leaders fought on the battlefield but Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu suffered a major defeat (Kapita 1976b, 41).

In 1900 Gert C. A. van Dijk, a former lieutenant class I, was appointed civil gezaghebber of Sumba. He approached his role with a more forceful military outlook.

In August 1901 rumours spread that Umbu Bidi Tau would attack the city of Waingapu on the full moon of 18 August (Kapita1976b, 41). The new civiele gezaghebber sent telegrams to Resident Heekert in Kupang and the Governor of Makassar calling for assistance (Kapita 1976b, 41). Reinforcements were immediately despatched to Sumba on the warships Java and Pelikaan from the port of Ampenan on Lombok (Kapita 1976b, 41). The Java arrived in Waingapu harbour on 25 August and the Pelikaan arrived later carrying the Resident of Kupang.

On 26 and 27 August 1901 Captain Dijk, with troops from Savu and Ende along with some Bugis as auxiliaries, attacked the seat of the Raja of Lewa-Kambera in Lambanapu. Faced with better-armed Dutch forces Umbu Bidi Tau was forced to flee, eventually finding refuge in the mountainous interior of Mahu - from where he would wage a long guerrilla war (Lee 1995, xix). Meanwhile the Dutch pillaged and burnt the homes of the Raja and his relatives. Having failed to destroy Umbu Bidi Tau's army, Resident Heekert ordered the ship Java to sail along the south coast and land its troops at Tidas. But Umbu Bidi Tau's warriors managed to avoid the Dutch forces, who were forced to return to the ship without success. Resident Heekert redirected the operations against Rindi, which had recently staged an attack against Mangili. Despite suffering huge losses the Raja of Rindi, Umbu Hina Marumata, was reluctant to surrender but finally did so to save the lives of his people. This whole conflict became known as the Lambanapu War. It was the start of the process that the Dutch euphemistically called ‘pacification’.

In 1902 Captain van Dijk controversially decided to place the landschap of Lewa-Kambera under the authority of the Raja of Tabundung, Umbu Tunggu Namu Paraingu, a move that had little support from its inhabitants because of the earlier conflict between the two domains (Kapita 1976b, 253; Wielenga 1927, 39).

Meanwhile on 12 April 1902 on Timor, Frits Anton Heckler had been appointed the new Resident of Kupang. He soon began to take a harder line, deposing the troublesome Raja of Larantuka in 1904, dispatching a gunboat to quell an uprising in Ende and intervening militarily to quash an insurrection in the Sikka area (Lewis 2014, 371-375).

Return to Top

The Dutch Reformed Mission

In about 1890 the Zending der Gereformeerde Kerke (Dutch Reformed Missionary Association) sent the missionary minister Rev. W. Pos to establish a post in Melolo. Just like van Alphen before him, he faced resistance from the local Sumbanese and only gained support from the resident Savunese. As a result of bad health he was forced to return to Holland in 1904.

That year the mission sent out Rev. D. K Wielenga, who chose Kambaniru as his initial base, as a second missionary pastor. However in 1905 a runaway Savunese slave burnt down the mission house and attacked Wielenga with a parang.

Later that year the Rev. De Bruijn arrived and based himself at the rebuilt mission station at Kambaniru, where he worked mainly among the local Savunese until 1927.

Wielenga realised that he needed to work with the Sumbanese community, so in 1906 he settled in Payeti, which was located on the coastal road between Waingapu and Kambaniru. There he persuaded Umbu Tunggu to donate land for the construction of a new mission and hospital. Its location was close to the Dutch military barracks, which should have offered enhanced security. Instead, it perversely led to another arson attack by dissident Sumbanese who were unhappy about the stationing of Dutch soldiers in the area. The mission was rebuilt and opened in 1907. Wielenga remained there until 1921 after which he returned permanently to the Netherlands.

Return to Top

Sumba from 1906 to 1942 – Under Dutch Colonial Rule

The successful military commander Joannes Benedictus van Heutsz had been appointed Governor-General of the Netherland East Indies in 1904, having previously gained control of the Sultanate of Aceh by means of a highly successful counter-insurgency campaign. This depended on the use of light and flexible detachments of military police (marechaussee), recruited from Ambon and Java. Faced with numerous ongoing local insurrections across the Outer Islands, van Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule. He would soon initiate a campaign throughout the East Indies which, despite being euphemistically called pacificatie or ‘pacification’, was in certain places brutally violent.

In March 1905 J. F. A. de Rooy took over the post of Resident of Timor from Heckler, charged with implementing this much more proactive Dutch policy. His main task was to establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the imposition of a new strategy towards all of the self-ruling districts. The former policy of non-intervention, in which the supreme authority was with the native rulers rather than the colonial authority, was to be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70). With regard to Sumba, de Rooy did not have to wait long to find a suitable reason to intervene. The Raja of Mamboro, Umbu Karai, soon led a raid against Kodi, passing without permission through Laura. There he threatened to settle some old scores with Umbu Lara Lunggi, the Raja of Laura, on his return journey. The latter appealed to the civiele gezaghebber in Waingapu for assistance, who in turn sent a letter to Kupang (Wielenga 1949, 30). To make matters worse there were more raids and the plundering of villages in the vicinity of Mamboro.

In March 1906 27-year-old Lieutenant Cornelis Adrianus Rijnders, the military commander at Kupang was despatched to Sumba, landing at Mamboro with 26 soldiers and 36 armed police (Kapita 1976, 48-50). Umbu Karai retreated into a rocky stronghold, but was pursued and within a few months captured and forced to pay a huge fine (Needham 1987, 28). The Dutch established two garrisons, one at Mamboro and one at Waikabubak, each staffed by a Dutch officer and about forty Indonesian soldiers. Sergeant Abbink was in charge of the Mamboro garrison and Lieutenant de Neeve was in charge of the fortified garrison in Waikabubak. Rijnders encountered no opposition in the other coastal domains, with even the powerful Raja of Rindi submitting without a fight (Wielenga 1949, 30). The real resistance took place in the interior, especially from the Raja of Lewa (Wielenga 1949, 32; Lamster 1945, 165).

Lieutenant Rijnders in 1912

Rijnders was appointed the civiele gezaghebber of Sumba in 1907, tasked with establishing peace throughout the island. In 1909 Rijnders turned his attention to the rebellious mountain region of Masu-Karera, which he only subjugated after establishing a military base at Kananggar in Masu (Wielenga 1949, 32). The entire population was eventually disarmed and registered.

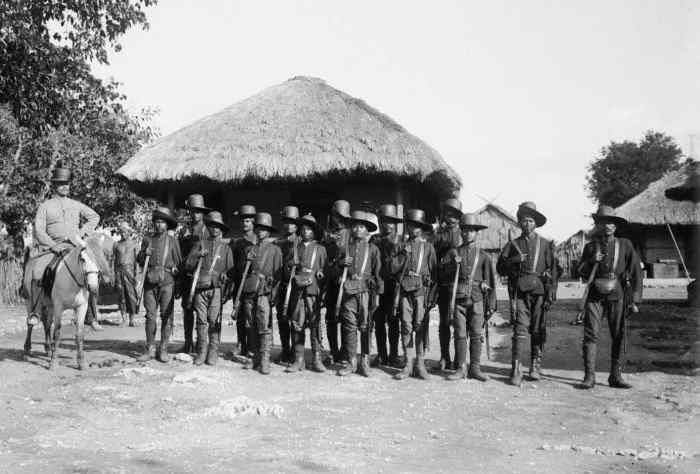

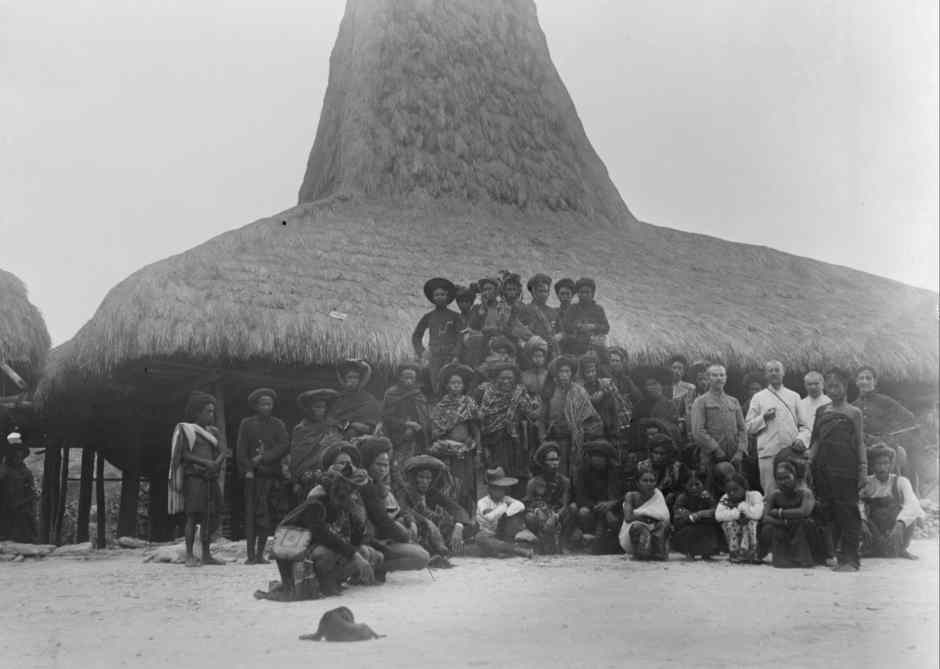

Posthouder Abbink and his squadron of military police at Mamboro around 1910

(Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

One resident around this time was the Dutch Protestant missionary Hendrik Hangelbroek. As he toured the island’s treeless interior, he discovered that in the interior nearly all of the villages were located on stony, high and difficult to reach hilltops. Even though the island had ample unused lowland farmland, the fear of a surprise attack forced the inland Sumbanese to locate their villages in difficult and inaccessible places, even though their women and girls had to daily descend and climb for at least half an hour to fetch water from the streams and rivers. He also encountered many burned down villages surrounded by overgrown gardens where the inhabitants had been robbed and murdered or captured, either by the marauding Endenese or by a vengeful Raja (1910, 92). Given the territorial fragmentation of the island into so many domains – Roo van Alderwerelt had identified 38 different tribes on Sumba, each headed by their own Raja, although there were undoubtedly more – he thought that it would be years before an orderly society was established on the island (1910, 94).

Yet as a degree of peace was gradually imposed, roads were constructed from domain to domain and from the coast to the interior. By 1910 the road from Waingapu to Mamboro was nearing completion (Heyden 1915, 104).

During that same year of 1910 the island was visited by two Dutch academics. The first was the scholar, ethnographic collector and adventurer Gerrit Pieter Rouffaer, who was attached to the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences on Java. He was undertaking his second trip to the East Indies during which he travelled across Sumba, creating an important photographic archive. In May 1910 he visited East Sumba including Parai Yawang, the royal kampong of Rindi.

The centre of Parai Yawang, Rindi, with the skull tree devoid of skulls

G. P. Rouffaer, 16 May 1910

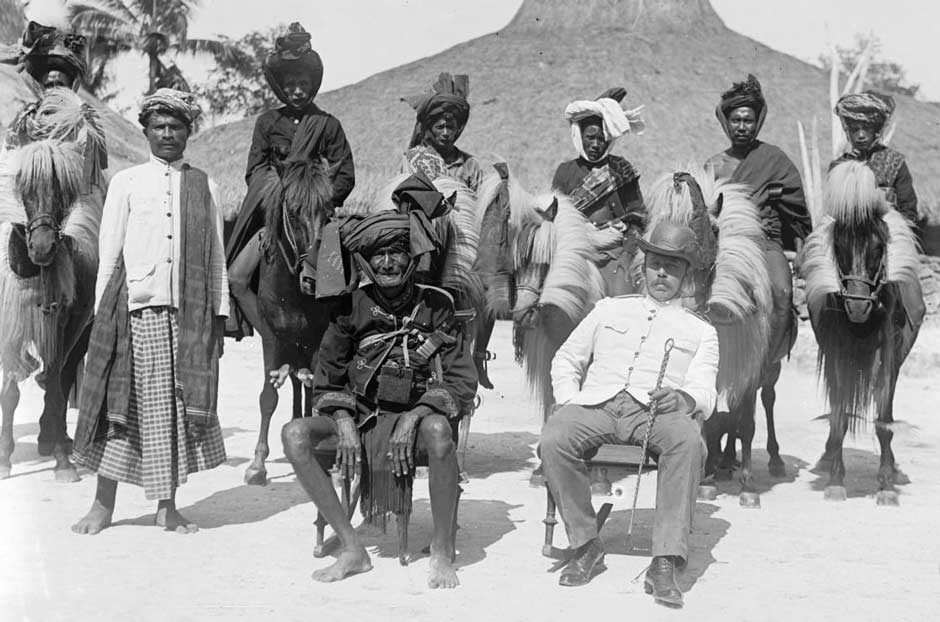

Raja Umbu Hina Marumata, aged about 65, with Major P. J. Spruit and a Savunese interpreter at Parai Yawang, Rindi. To their rear are six warriors on horseback, the horses decorated with goat hair tungga. G. P. Rouffaer, 16 May 1910

A group of Sumbanese in Parai Yawang seen from the house of the Radja of Rindi

G. P. Rouffaer, 16 May 1910

The chiefs of Masu and Karera in 1910

G. P. Rouffaer

In November 1910 Rouffaer visited West Sumba with the missionary Wielenga.

Above: A group of Sumba chiefs at Karuni in Laura, West Sumba, together with Lieutenant Rijnders, Lieutenant Streiff, Sergeant Abbink, Dr Wielenga and one of the wives of the Radja. Below: Kampong Sodan in Lamboya, West Sumba

At the same time Herman Witkamp, a geologist and mining engineer working for the Bataafsche Petroleum-Maatschappy, travelled extensively across the island for three months, from May to August 1910. He was told by Wielenga that it was still not possible to visit the central part of East Sumba because of the unstable situation there (1913, 495). Despite Rijnders attempts to pacify the island, there was still widespread unrest, much of it directed at the Dutch occupiers.

The centre of Parai Yawang photographed by Herman Witkamp in 1910

In 1908 Umbu Nai Laki, the Raja of Masu, had succeeded in wiping out a Dutch patrol, killing its commander, Sergeant Siegers. Despite a shortage of soldiers, limited Dutch reinforcements were sent to Masu but yhey were ineffective in controlling the situation. In 1909 the village of Wewewa in West Sumba refused to provide corvee labour or pay the new taxes imposed by the Dutch, and destroyed a Dutch military post. Also in 1909, villagers in the Lamboya area led by Umbu Tadu Meli took up arms and succeeded in killing the Dutch military commander, Lieutenant de Neeve. The Dutch retaliated by brutally suppressing the uprising and Umbu Tadu Meli was captured.

In 1911 work was underway constructing roads in various parts of the island using highly unpopular conscripted labour, which inflamed resistance against the military supervisors. That year a rebellion broke out in Kodi Bokul led by its chief, Ratu Loghe Kandua. Having been tasked with supplying heavy labour to build the main road in Kawango Wula, including a bridge across the Kodi River, local villagers reacted to the harsh treatment handed out by the army officers who were supervising the project (Kapita 1976, 49). After Dutch forces retaliated, Ratu Loghe Kandua asked the chief Wona Kaka to assemble a war party. Captain Dijkman led Dutch forces against the insurgents and, although many Dutch troops were killed, his forces succeeded in killing the Raja, which only inflamed the situation.

During 1911 Rijnders retired as civiele gezaghebber and was replaced by A. G. L. F. van Krieken, who only held the role until 1912, by which time a modicum of order had finally been achieved as the rebellious Rajas had progressively been arrested and sent into exile. A. J. L. Couvreur, the former controleur of Ende, took over as the controleur of Sumba from May 1912 until March 1914, during which time the Dutch imposed its first system of more direct colonial rule. The whole of Sumba was established as one afdeeling within the Residency of Timor, divided into four sub-departments or onderafdeeling, each composed of a number of self-governing sub-districts or zelfbesturende landschap, later known as swaprajas or 'autonomous regions' (Wellum 2004, 26). The onderafdeeling and their nineteen landschaps were as follows (Kapita 1976b, 51-53):

Onderafdeeling |

|

Administrative |

Landschaps |

Sumba Timur |

East Sumba |

Melolo |

Umalulu, Rindi-Mangili, Waijelu and Masu-Karera |

Sumba Tengah |

Central Sumba |

Waingapu |

Lewa-Kambera, Tabundung, Kanatang, Napu and Kapunduk |

Sumba Barat Utara |

Northwest Sumba |

Karuni |

Laura, Mamboro, Kodi, Mbangedo and Waijewa |

Sumba Barat Selatan |

Southwest Sumba |

Waikabubak |

Lauli, Wanukakka, Lamboya, Anakalang and Lawonda |

Each onderafdeeling was led by a civiele gezaghebber, reporting to an Assistant Resident domiciled in Waingapu. Sergeant Abbink retained his post at Mamboro and Lieutenant J.J. Berendsen was stationed in Waikabubak.

The four onderafdeeling of Sumba. Copyright Vel 2008.

Couvreur also introduced the first tax system in 1912, in which villagers were obliged to pay a ‘head tax’ either in cash or in the form of free labour. Its introduction was highly unpopular and faced difficulties because of the lack of currency in circulation and people’s lack of familiarity with coinage in an economy based on barter. However by 1914 Couvreur was able to report that payment in kind was no longer found in West Sumba. Couvreur found many of the regional leaders difficult to deal with, describing them as ‘robber barons and destroyers of their own land’, only concerned with increasing their status and power (Couvreur 1917, 218).

When work resumed on building a road across the island in 1912, villagers near Waikabubak staged a night-time raid on the military barracks. Lieutenant Berendsen was nearly slain and his entire troop of native soldiers were killed (Kapita 1976b, 49). Almost three years of guerrilla warfare, known as the Wonakaka War, was eventually brought to an end by forcing the insurgents to return to their ancestral villages and by burning their crops.

The subjugation of Wonakaka by the Dutch, mistakenly dated 1903

During 1913, and later in 1916, a selection of the most trusted leaders of local noble clans (marimba) were selected as hereditary 'independent administrators' (zelfbestuurder) or Rajas of each onderafdeeling, most of which were comprised of two or more traditional, formerly independent domains (Forth 1981, 12-13). Thus, for example, in East Sumba the northern part of Mangili was joined to Rindi to form the sub-department of Rindi-Mangili, headed by the Rindi noble ruler, Hina Marumata. In return for Dutch support the Rajas were burdened with the responsibility for tax collection.

The Main Heads of the Zelfbesturende Landschappen

Landschap |

Bestuurder |

Date of Appointment |

Melolo |

Umbu Hina Hamatake |

23 Dec 1913 |

Rendi |

Umbu Hina Marumata |

23 Aug 1916 |

Waijelu |

Umbu Tangga Teul Atakawawo |

23 Dec 1913 |

Tabungung |

Umbu Tunggoe Namoe Paraing |

12 May 1916 |

Kanatang |

Umbu Nai Haru |

12 May 1916 |

Napu |

Umbu Landu Kura |

12 May 1916 |

Mambro |

Umbu Kraing (retired) |

22 Sep 1916 |

Laura |

Ama Biri Kalumbang |

23 Dec 1913 |

Kodi Belagar and Kodi Bengedo |

Riedja Konda |

n/a |

Kodi Bokol |

Dera Woela |

3 May 1913 |

Kapunduk |

Umbu Nai Taku |

12 May 1916 |

Wadjewa |

Umbu Pati |

23 Dec 1913 |

Masu-Karera |

Umbu Nai Laki aka Umbu Domu Landu Wulang Djongga Meamang |

23 Dec 1913 |

Lauli |

Dange Lade |

23 Dec 1913 |

Lamboya |

Kedu Moto |

23 Dec 1913 |

Lewa |

Bidi Tau Umbu Djama Karai Mandjawa |

12 May 1916 |

Anakalang |

Umbu Ngailu Diddu |

23 Dec 1913 |

Lawonda |

Umbu Sewa |

28 Sep 1916 |

Wanokaka |

Badju Padeda |

12 May 1916 |

(Source: Voornaamste Hoofden van Inlandsche Zelfbestuurende Landschappen, Regeerings-Almanak voor Nederlandsch-Indïe, 1917)

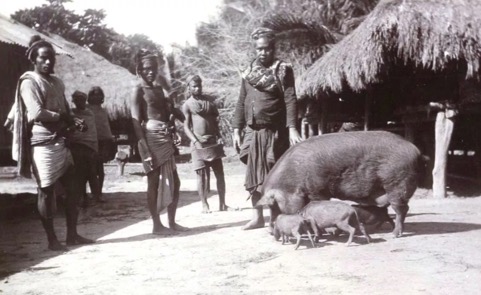

Umbu Laramessa in Kambera in about 1912 with his treasures: slaves and pigs. Collection of G. S. Vriburg

Crossing a river with horses on Sumba, about 1912

The increasingly stable political situation encouraged Dutch missionaries to come to the island and to open up churches and schools. As a result of the Flores-Timor Agreement of 1913, the whole field of education on Sumba was entrusted to the Protestant Mission, with the costs heavily subsidised by the colonial government in Kupang (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 323). Later that year the education expert Tjalling van Dijk came to Payeti to oversee the development of the nascent education system, setting up a teachers' training course the following year.

During 1913 the Protestant missionary F. J. Colenbrander arrived in Melolo, while L. P. Krijger arrived in Karuni. Earlier in 1912 the first Catholic SVD missionary had arrived on the island. Schools were opened in Baing (Waijelu) in 1912, and in Matawai (Mangili), Parai Yawang (Rindi) and Kananggar (Masu) in 1913. Primary schools opened in Payeti (Kambera) in 1914 and in Karuni in 1920. However, unlike the local Savunese, the Sumbanese were reluctant to send their children to school. Indeed, a school that had opened in Lai Handung in 1910 was burnt down soon after it opened. In Waijelu the new school failed to attract sufficient pupils.

Dutch surveyors conducted a detailed mapping of the island in 1914, the results of which were published in Batavia in 1915. By now a main east coast road ran from Waingapu all the way south to Baing in Waijelu. A secondary road ran westwards from Melolo to Kanaggar, where it divided into one route heading north through Masu half the way back to Waingapu, and another heading south through Karera almost reaching the south coast. A second main north coast road ran westwards from Waingapu to Karoni via Palamedo and Mamboro. From its western end, three secondary roads ran south to connect with Waikabubak.

A sketch map of Sumba published in 1915

Despite the enhanced Dutch presence, there was still limited resistance in West Sumba against colonial rule. During 1916 there were rebellions in Tanah Maringi, Wewewa, and Anakalang. In the latter case, the Dutch finally captured the rebel leader Gauka and many of his supporters.

Above: Uma Bara in Umalulu in 1917, showing the Raja’s house and the skull tree

Below: The house of Umbu Nai Tanga in Tai Manuk, sketched by Otto Nieuwenkamp in 1918

By now Waingapu had grown into a sizeable settlement, the main economic centre of the island. The busy harbour could accommodate KPM steamers, which were able to moor directly at the end of a long stone pier.

Above: Waingapu harbour in 1920, Museum für Volkenkunde

Below: The harbour and pier, Waingapu, undated

In 1922 the two onderafdeeling of West Sumba were recombined to form the single onderafdeeling of Sumba Barat with its capital in Waikabubak, while the onderafdeelings of Central Sumba was merged with East Sumba to form the single onderafdeeling of Sumba Timur with its capital in Waingapu.

Although the conflicts between the various landschappen had been significantly reduced, slave ownership by the maramba remained unchanged and the tradition of human sacrifice continued. The missionary A. C. Kruyt reported in 1922 that war captives or outsiders taken prisoners were sometimes sacrificed at the funeral of important nobles in East Sumba.

In 1925-26 there was a rebellion in Napu, the northernmost landschap of Sumba, against the payment of taxes and forced labour. It was led by Reku Landurang and supported by Umbu Ndilu Danguramba, the chief of Napu, and Umbu Nai Tahu, the chief of Kapunduk. The resistance was suppressed by the Dutch, the two chiefs were removed and the Napu and Kapunduk landschaps were abolished and merged with Kanatang (Kapita 1976, 56).

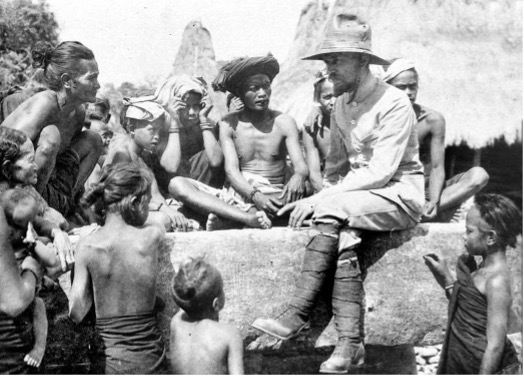

The Protestant missionary, Wiebe van Dijk, preaching to villagers around a Sumbanese tomb

ca 1925–1929

The Resident of Timor, C. Schultz (centre), in Waingapu in 1927 during his farewell tour of duty. On the left W. K. M. Stibbe, on the right Schultz's predecessor, A. J. L. Couvreur

Missionaries and administrators were not the only visitors to arrive in Waingapu at this time. The newly-built Dutch hydrographic survey ship HNMS Willebrord Snell arrived in Surabaya in May 1929, setting off from there on the first leg of its expedition focussing on the oceanography of the deep basins, geology and biology of the coral reefs and the creatures living on them. The ship arrived in Waingapu harbour in November 1929. The expedition leader, P. M. van Riel, and the ship’s captain, Lieutenant F. Pinke, were welcomed by Assistant Resident Young and taken for a drive into the hilly interior.

Rindi with the skull tree and a new tomb

Photographed by J. Sibinga Mulder in 1930

The Raja of Anakalang and two nobles surrounded by bodyguards, 1930

Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

In 1930 Assistant Resident Young was replaced by L. C. Heyting, who had previously been the controleur of Central Lombok. That same year a hospital was opened in Waikabubak. There was already a hospital in Payeti (run by the mission), as well as polyclinics in Mangili (led by H. Radamuri) and Melolo (run by a nurse from Java), and surprisingly in rural Kananggar (led by M. Mbaku).

A line of logs for pulling a sledge supporting the capstone of a tomb in East Sumba

Photographed by L.C. Heyting in 1931

The Dutch office staff in Waingapu bidding farewell to the Assistant Resident of Sumba, L. C. Heyting (seated in the middle), on his return to the Netherlands, 1933

The individuals in the above photograph are as follows: Seated third from the right: Lieutenant Governor K. Helder. Second row from left to right: Acting Raja Taku Geli of Laura, Raja Umbu Pati of Waijewa, Raja Dera Wula of Kodi, ex-regent Raja David Bulan of Kodi Belagar and Kodi Bengedo, Raja Koki Daha of Lauli, an unknown administrative official, Acting Raja Umbu Mohamad of Mamboro , Raja Umbu Mbili Ngemunasa of Umbu Ratu Nggai, Raja Umbu Sapi Pateuku of Anakalang, Raja Guling Manjoba of Wanokaka, and the Chairman of the Regency Council, Eda Bora of Lamboya.

In the early 1930s the horse export trade from Sumba to Java suffered an economic downturn caused by the Great Depression. By now the trade was controlled by a single company, Mohamat Aldjuffrie & Co., which had its headquarters in Waingapu and representatives in East Java. It was run by Shafi’i Muslims whose families originated from Hadhramaut in southern Arabia.

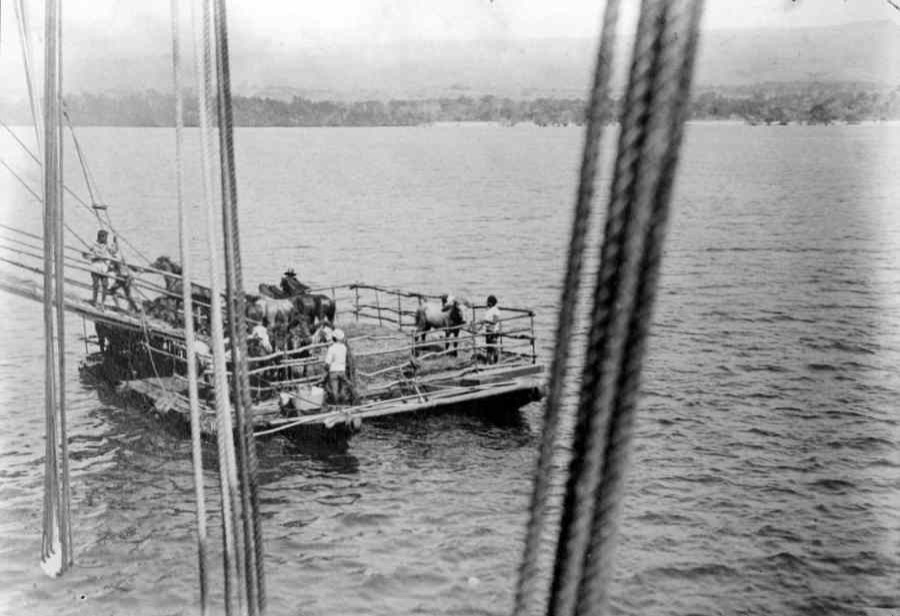

Loading horses onto a steamer from a raft at Waingapu, undated

Since the start of pacification in 1906 the island had remained under the control of the military and it was only in 1933 that the security situation had sufficiently improved that the last Dutch military detachment could be replaced by the civil police (Needham 1987, 27 and 29).

Janet Hoskins (2004, 95) emphasised the different political systems prevailing in East Sumba and West Sumba at this time, quoting J. I. N. Versluys, a Dutch tax collector who was stationed on Sumba during the 1930s:

In the east ..... life is centred on the big houses of the aristocrats, who live with their servants or slaves in relatively autonomous fashion ..... Stock breeding is of great importance, and the population is sparse ..... On the contrary in the west, we see huge plains of wet rice fields and a great many swidden gardens ..... and a much denser population. There is greater economic equality, since livestock are distributed over a larger number of owners, and this accords with the total social structure, where the figure of the aristocrat who can live as a separate entity with his family and servants is much rarer.

In East Sumba people lived in a few strictly hierarchical domains, headed by an aristocratic chief, while in the more numerous and competitive domains of West Sumba wealth was less concentrated and political life was dominated by lower-status leaders who fought for authority through feasting and warfare.

In the mid 1930s the Dutch civil servant/ethnologist Christiaan Nooteboom was stationed in East Sumba for over 1½ years. He noted that at that time there were two main government highways. The first ran from Waingapu through the south of Kanatang onto the Lewa plain and from there via Lakoka to Waikabubak. The second ran from Waingapu through to the coastal plain to Melolo and from there via Rindi and Mangili to Waijelu (Nooteboom 1940, 11). It was even possible to reach Kanaggar by car.

In Nooteboom’s opinion, after decades of work the Dutch Reformed Church mission had accomplished very little among the Sumbanese community, most of their converts being Savunese. Their main achievement had been the establishment of numerous schools, maintained through government subsidies, which provided a small section of the younger generation with an elementary education in reading, writing and arithmetic.

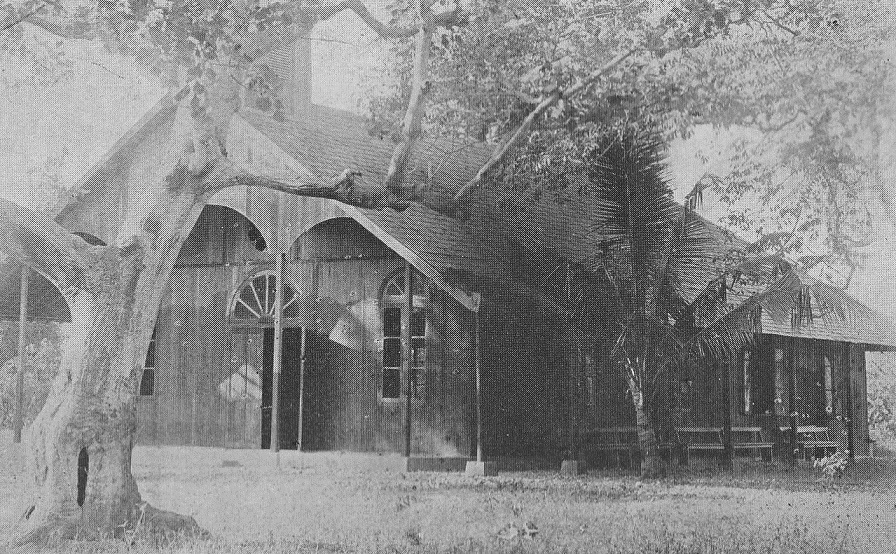

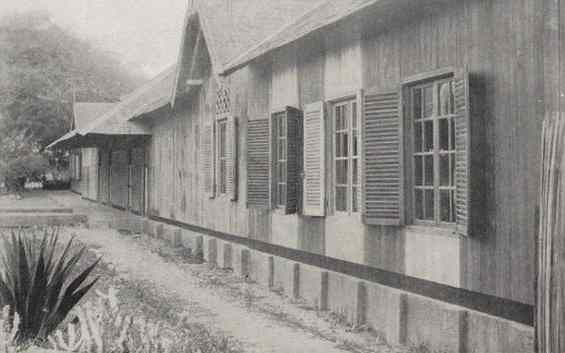

Above: The wooden church at Payeti in 1921. Below: The school at Payeti, around the same time.

The Catholic church in Waingapu, 1938-1940

In December 1938 school inspector Tjalling van Dijk handed over his duties to his successor, J. L. Erkelens. By now there were 70 ordinary schools, 2 standard schools and 2 high schools across the whole of Sumba (Kapita 1976b, 64). Yet by 1942 Sumba still only had two hospitals and eight polyclinics.

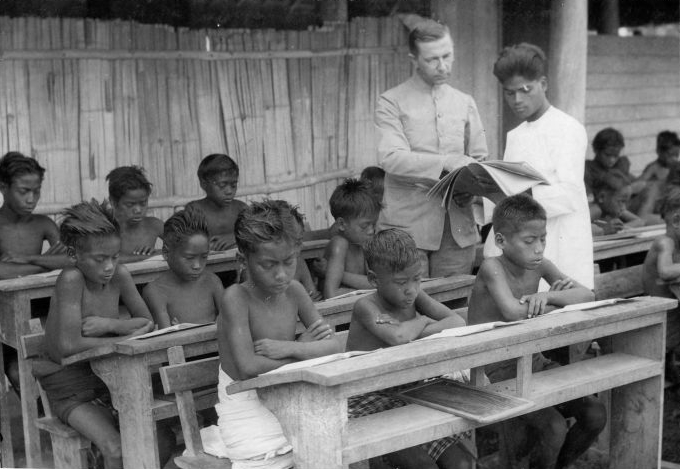

The school superintendent Tjalling van Dijk inspects a family-run village school on Sumba. Undated but clearly pre-1938

During the late 1930s horse exports to Java recovered, stimulated by Dutch military purchases following the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. By now Mohamat Aldjuffrie & Co. controlled most commercial activities on Sumba apart from maritime transport. The company was run by Sayyid Muhammad bin Abd al-Qadir al-Jufii and his brother Umar (Clarence Smith 2009, 147).

In 1940 Umbu Rara Meha, the Raja of Lewa-Kambera, died and was succeeded by his only son, Umbu Nggaba Hungu Rihieti, located in Prailiu. Umbu Wunu Hewalu Karaminiawa alias Umbu Nai Ndima based in Lewa was appointed assistant Raja (Kapita 1976b, 56).

The statue of Tamu Umbu Rara Meha in Waingapu

Return to Top

The Looming Threat of War

Dutch officials throughout the Netherland East Indies must have been fully aware of the deteriorating international situation from the mid-1930s onwards. Germany had occupied the Rhineland in 1936, followed by the Sudentenland in 1938. Then in the spring of 1939 Germany invaded Bohemia and Moravia, while Italy invaded Albania. After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Britain and France responded by declaring war on Germany on 3 September.

On 10 May 1940 after the pause known as the Phoney War, Germany began its blitzkrieg assault on the neutral Low Countries of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, rapidly moving into France. Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government immediately fled to London.

Meanwhile Japan had invaded China in 1937 and occupied Hainan Island in 1939. In 1940 it invaded French Indochina, bringing the British possessions of Malaya and Singapore along with the Dutch East Indies in reach. For some time the Japanese had seen the East Indies as a crucial source of strategic raw materials – oil, rubber, tin and bauxite – and in 1940 began negotiating to acquire these supplies by peaceful means. However progress stalled following Japan’s signing of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in September 1940.

The Dutch government in exile had mixed views on how to deal with Germany and Japan and seemed paralysed with inaction. Surprisingly it was not until November 1941 that they began preparing for war with Japan, sending Dutch naval ships based in the Indies to sea and mobilising the KNIL army and air force. Following the Japanese attacks on British Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong and the bombing of the US fleet at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands declared war on the Empire of Japan the following day.

Return to Top

Bibliography

For the bibliography please click here.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 11 March 2023.