Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Textiles of Kisar Island

Kisar Textiles in the Nineteenth Century

Kisar Textiles in the Twentieth Century

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 2

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 3

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 4

The Textiles of Kisar Island

Tiny Kisar developed into the most important and influential weaving centre in South West Maluku. Brigitte Khan Majlis described the distinctive style of Kisar textiles as one of the most impressive in Eastern Indonesia (Khan Majlis 1984, 121).

Kisar Islanders dressed in modern festival costumes in Wonreli

(Image courtesy of Hilary Hopkins)

By the early nineteenth century tiny Kisar had become the wealthiest island in the South Western Archipelago, thanks to its industrious people, fertile agriculture, and tradition of inter-island trading. The best textiles in the South West Islands were produced on Kisar, Leti and Luang (Jacobsen 1896, 132), but those from Kisar were the finest and were apparently only rivalled by those from tinier Luang in the Sermata Archipelago, 165km east of Kisar. The minority Oirata-speaking community of Kisar, who live in the two villages of Oirata Barat and Oirata Timur, produced the best textiles of all.

Kisar textiles were greatly valued and were exported to many of the neighbouring islands. According to Kolff, in 1825 they were being exported to Leti, Moa, Wetar, Romang and Damar and even further afield to Tanimbar (Kolff 1840, 257). Almost a century later Jasper and Pirngadie identified the main export territories as Alor, Wetar, Timor, Moa, Babar, Tanimbar and Aru (Jasper & Pirngadie 1912, 276). Riedel, on the other hand, found that the islanders traded with Bugis and Makassarese merchants, bartering their sarongs, loincloths, waist belts, sheep and goats in return for Makassar sarongs, coloured linen, and even patolas (Riedel 1886, 426).

Weavings from Kisar are primarily a product of the Austronesian world – foreign influences have been slight. Early ikat designs may have been brought to Kisar, East Timor and possibly other parts of the Lesser Sunda Islands by a late wave of Austronesian immigrants from south Sulawesi. They appear to have only arrived roughly a thousand years ago, before which the inhabitants of this region spoke only dialects of Papuan (Hull 1998,149-53). They introduced a new style of two-panel tubeskirt, with a narrow warp-striped centre enclosed by a pair of broad warp ikat bands composed of square-shaped motifs, finished at each end with wide, plain black end bands.

Over the subsequent centuries there has been regular two-way intercourse between Kisar, East Timor, Luang and the other neighbouring islands, further influencing local textile designs. The arrival of some 500 Fataluku-speaking immigrants from East Timor in 1721 probably injected new motifs into an already well-established local repertoire. Many of the motifs found on Kisar textiles made during the past one and a half centuries have close similarities with those found in the far eastern part of Timor Leste. Some motifs classified as rou are restricted designs that in the past were confined to specific aristocratic families and even today can only be made and worn by a specific clan or domain (Engelenhoven 1998).

Non-Austronesian contributions to Kisar textiles seem to be minimal, limited to a couple of motifs – one originating from India and the other from Habsburg Spain.

Return to Top

Kisar Costume in the Nineteenth Century

Our understanding of the evolution of Kisarese textiles and costume during the colonial period is very much conditioned by the limited and piecemeal descriptions provided by Dutch and other European visitors. Their reports are often unbalanced, firstly because their authors were liaising with the island’s chieftains and nobles rather than its ordinary people, and secondly because the minority mestizos community (descended from former Dutch and other European soldiers stationed on the island) received far more attention than the native population.

The earliest interesting snippet was penned by the Leiden botanist, Professor Willem Hendrik de Vriese, who published the details of a voyage to eastern Indonesia by his predecessor Professor Casper Georg Carl Reinwardt, undertaken in 1821. When Reinwardt arrived on Kisar, Raja Utanmeru Zacharias Bakker was absent so he was welcomed by the Raja's wife, whose costume he did not describe. He did report that the descendants of the Europeans were quite wealthy men who had many slaves, up to three hundred in the case of the Raja, all of who went naked apart from a loincloth, which they wore as a belt as well as a kind of apron (De Vriese 1858, 371).

Some four years later Lieutenant Dirk Kolff, the captain of the Dourga, gave a much more detailed description. This time Raja Utanmeru Zacharias Bakker was present on the island and Kolff and his officers met with the island’s chief, along with all of the district orang kayas and the residents of the main village – in other words, the island’s ruling nobility. The village was Wonreli but he mistakenly called it Marna, after the island's noble caste. The majority of its inhabitants seem to have turned out in Dutch national costume, although some were dressed in native sarongs and kabayas:The costume of the natives was rather singular. They had naturally clothed themselves in their best on this important occasion, some wearing old fashioned-coats with wide sleeves, and broad skirts; others garments of the same description, but of a more modern cut, while the remainder were clad in long black kabyas, or loose coats, the usual dress of the native Christians. The costume of those who were clad in the old fashioned coats was completed by short breeches, shoes with enormous buckles, and three-cornered or round felt hats of an ancient description. Many of the women wore old, Dutch chintz gowns or jackets, the costume of the remainder being the native sarong and kabya. The heads of the women were adorned with ornaments of gold and precious stones, but the men wore their long hair simply confined by a tortoise-shell comb, after the mode adopted by the native Christians of Amboyna (Kolff 1840, 53).

Sadly Kolff failed to provide a similar detailed description of the ordinary ‘native’ costumes. However he did note that the Kisarese routinely visited Wetar to barter cloth, iron and gold in return for sandalwood, rice and Indian corn (Kolff 1840, 42). Interestingly on Damar, where the natives also wore barkcloth loincloths, Kolff discovered that imported European or Indian cotton cloth was scarce and expensive due to the limited amount of trade (Earl 1837, 369-370).

In 1838 the Englishman George Windsor Earl visted Kisar, hoping that it might become a supply source for the new British colony of Port Essington on the north coast of Australia. He discovered a small trading emporium, with goods including cottons imported by island traders in exchange for agricultural produce and native textiles:

The women manufacture considerable quantities of cloth from the cotton produced on the island, the greater portion of which is disposed of to the people of the neighbouring islands. The yarn is dyed before the cloth is manufactured. The red is produced from the Morinda citrifolia; the blue from a small plant, which is common also at Sydney, and called 'native indigo'; the yellow dye is obtained from a wood of that colour;

The Dutch Protestant minister Dr Wolter Robert Baron van Hoëvell visited Kisar in the 1840s and was of the opinion that its inhabitants spent very little on their clothes (Van Hoëvell 1855, 227). People dressed up for attendance in church, some of the descendants of the Dutch (mestizos) making the most effort, while the other Christians (presumably the males) wore a black kabaya and trousers. For the rest of the week the men wore only a loincloth, described as a tjidaki (equivalent to a tjawat or cawat). He did not record what these were made from, although did note that the men on neighbouring Leti went naked apart from a crude barkcloth loincloth. A barkcloth jacket and a barkcloth loincloth from Kisar, held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, are listed respectively as a rain rorau and a 'kornele, he' (Juynboll 1932, 106). The women and children wore sarongs that were very strong and were woven from local cotton, which grew widely across the island. The sarongs were mainly produced for personal use, but some were traded to Wetar and Romang. Textiles were also supplied to Bandanese and Makassarese merchants who arrived annually between October and January.

When H. C. Van Eijbergen arrived on Kisar in 1862 he found that the islanders produced excellent straw hats (stroohoden), toedoengs and dresses (Eijbergen 1864a, 197). He visited some of the mestizo families in their 'shabby' homes and found that they were very poor. He was saddened to see mestizo men and youths working in the gardens wearing only a loincloth or tjidako (Eijbergen 1862b, 137).

Incidentally a Kisar sarong in the collection of the Museum of the Batavian Society was described in 1868 as a kain oeti-oeti (Norman 1880, 149). Among the Oirata a kain uta-uta would be a woven cloth.

Our most comprehensive picture of late nineteenth century Kisar textiles is provided by three visitors who arrived in the 1880s – the Resident of Ambon, Johann Gerard Friedrich Riedel, who visited Kisar in 1882, the following Resident of Ambon, G. W. W. C. Baron van Höevell (the nephew of the minister Dr W. R. Baron van Hoëvell), who came in 1887 and the Norwegian ethnologist and collector Johan Adrian Jacobsen, who visited in 1888.

Riedel observed that the women had small, pear-shaped breasts with black halos, suggesting that they mostly went bare-breasted. This observation, coupled with earlier reports that the native female aristocracy wore kabayas over their sarongs for attendance in church, points towards the influence of the Dutch Protestant Mission - at least on the population of Wonreli - during the earlier part of the nineteenth century.

Riedel was of the opinion that the women of Kisar spent very little on their dress because clothing was regarded as a burden. Even the Christians and the descendants of the Europeans only clothed themselves properly for ceremonial occasions or in the presence of strangers. The favourite colours were red, memeere, and yellow, mamarre (Riedel 1886, 405). Riedel found that the mestizos had not only adopted Kisarese manners and customs but also Kisarese clothing. For formal occasions the men donned European clothes, while the women wore a sarong and kabaya blouse (Riedel 1886, 401). Perhaps this is not surprising, given that the soldiers from the Dutch garrison had married local Meher-speaking women who presumably maintained their traditional style of weaving. The mestizo women wove snikirs or shawls that were greatly valued on Timor Island. Riedel provided illustrations of two examples:

Patterns woven on snikirs or shawls by the mestizo women of Kisar

(Riedel 1886, plate XXXIX)

Women's costume(nainair mawehke) consisted of the following (Riedel 1886, 424):

- a short sarong (homonon jotowawa) that hung from the loins to below the knees

- a presumably longer sarong (homonon kapaije) that draped over the shoulder. Note that in Dutch a kapje is a cap or little hood (Holtrop 1801, 369).

- hairpins (kurkupni)

- a buffalo horn comb (naham arapau duhudle)

- gold earrings (mahe klinni)

- neck corals (loi kelenne) and

- bracelets of buffalo horn or ivory (leli)

- a black raine memehkem blouse.

On ceremonial occasions, women adorned themselves with various items of gold jewellery:

- a golden comb (nahamahe),

- golden hairpins (aukaukau mahe),

- gold neck chains (mahe rante) and

- gold bracelets and rings (leli and delië mahe).

The women, just like the men, had pierced earlobes for inserting pendants and rings as well as flowers and feathers.

Men’s costume (nainair mooni) was composed of the following (Riedel 1886, 423-424):

- a loincloth (waare) made of Kisar cloth,

- a decorative headdress (rapanulu) made from the leaves of the koli palm (Borassus flabelliformis),

- a headscarf (lense wuhuku uluwahkun),

- neck corals (paame),

- bracelets of buffalo horn (leli arapau duhudle),

- a bracelet of lontar palm leaf for young men (sepelau),

- a belly-band (kornelhe),

- a shawl (hoire) and

- a bamboo comb (nahamoure).

Riedel is imprecise in his descriptions, subsequently noting that waare were manufactured from the bark of trees of the Ficus species, only to later inform us that one waare was traded for one patola, suggesting that it could also be a valuable weaving.

Men wore gold rings (doli mahe) for ceremonial occasions.

With the exception of the Christians, all of the men wore their hair long. The chiefs and elders grew moustaches and beards (Riedel 1886, 404-405).

The men were well-armed and stored their weapons above the living part of the house. These included lances (keere), lances with iron barbs (keere ai aike), bows (raame), arrows (raame ihië), swords (raae), Dutch swords (rawaladi), flintlock rifles (ilke), guns (poutudeule), bamboo lances (kermulu) and baskets of stones - the Kisarese were apparently very formidable stone-throwers.

When a person died their body was bathed and wrapped in a variety of textiles – two Kisar sarongs, a length of white linen, a snikir or shawl and a patola sarong – before being placed in a coffin or wrapped in mats (Riedel 1886, 420).

The terms senikir and snikir were also used to describe textiles on a couple of the other nearby islands, such as Moa (Riedel 1886, 382). On Babar the term snikir was applied to a loincloth (schaamgordel) but, surprisingly, the same male textile was also used as a head cover by female attendants mourning at a funeral (Riedel 1886, 338, 344 and 360). The term senikir was also used by the Tobu Tihu of the Tihu Lake area of Wetar Island to describe a large selendang (Elbert 1912, 246).

Not long after Riedel’s visit, the Koloniaal Museum in Amsterdam (the predecessor of the Tropenmuseum) received a snikir from Kisar, describing it as a selendang or shawl. It had been woven by the female descendants of the former European garrison (Maatschappij-Belangen 1897, 337).

Riedel reported that Makassarese, Bugis and other foreign merchants visited Kisar every year between October to January to trade in textiles and other commodities (1886, 426). The Kisarese would barter one sheep for a Makassar sarong, one goat or one Kisar homonon awahe for two Makassar sarongs, a waare loincloth made from Makassar cloth for a patola sarong, a kornelhe bellyband for headscarves and 10-18 mats for a piece of white, red or black linen.

We have no idea how many patolu eventually reached the island, but those that did were highly valued – almost on a par with gold. For example, if an arranged marriage between the children of brothers and sisters (agreed when they were just 5 to 7-years-old) was subsequently broken, the adat fine amounted to two gold discs, two buffalo, one Makassar sarong and one patola (Riedel 1896, 416). Patolu were also used on Kisar as funeral shrouds (Riedel 1886, 420).

Interestingly on Romang, where the people claim to have originated from Kisar, Riedel discovered that women were also weaving graceful homonon awahe, senikirs, sarongs and shawls, which were being sold to foreign traders at good prices (Riedel 1886, 460).

When Baron van Höevell arrived on Kisar in 1887 he showed more interest in the mestizo minority of Kota Lama than the native population. He seemed surprised that the mestizos worked in the hot tropical sun to plant cotton, just like the Kisarese natives (1890, 217). The mestizo women dressed in a sarong and kabaya, while their more important men wore European costume, the others dressing like the residents of Ambon. The mestizos braided straw hats and the women wove 'excellent' cloths and selendangs.

Van Hoëvell was of the opinion that the trade of Kisar Island was entirely independent of the Makassarese and other foreign merchants and very much in the hands of the mestizos who sailed to Dili in East Timor every year using prahus that they obtained from Luang. They traded the sarongs and snikirs (selendangs) woven by their wives, along with some pigs, chickens and oranges, for European textiles, chintzes and gold coins, the latter to be processed into jewellery. The number of textiles exported in 1887 amounted to 300 sarongs valued at 12 Florins each and 350 snikirs valued at 8 Florins each (1890, 231). Sadly van Hoëvell did not report the imports to Kisar but did show that Leti Island imported packs of yarn (30 in 1886 and 70 in 1887) as well as chintzes and soft madapolam cotton fabrics (80 and 250 respectively). Clearly commercial machine-spun yarns were already making their way into the South Western Islands.

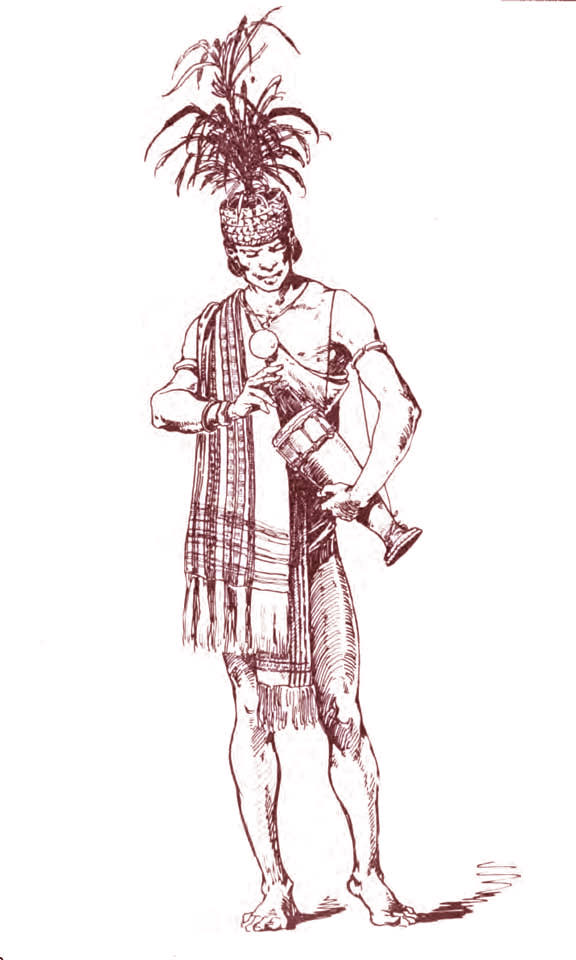

The Norwegian ethnologist and collector Johan Adrian Jacobsen led an expedition to the Banda Islands in 1887-88, tasked with collecting ethnographical artefacts for the Museum fur Völkerkunde in Berlin. He sailed from Hamburg aboard the Frigga, reaching Kisar on 18 February 1888 after having visited Maumere, Larantuka, Alor and Wetar (Jacobsen 1896, 1). After initially landing at Purpura beach, he spent five days exploring the island during which he made limited notes on the costume of the local people.

After leaving Purpura on a hike to Wonreli, Jacobsen saw many natives tilling the black soil with pointed sticks, standing in long rows and singing, sometimes to the sound of a bamboo drum. Supervised by a guard, they were probably slaves working for the orang kaya of Purpura. They wore flat hats and loincloths, the latter termed a kornele (he), or weraü or werneau (Jacobsen 1896, 117-118). Jacobsen was told that these loincloths were tied tightly to diminish the feeling of hunger, 'a sensible measure to ensure that breakfast breaks did not shorten the time for work'.

Agricultural labourer on Kisar (Jacobsen 1896, 117)

At the celebrations for the birthday of the King of Holland, the mestizos (Walada) ‘tormented themselves' in white shirts, black skirts, European hats and even canvas shoes, while the natives went naked apart from ‘a simple loincloth’ (Jacobsen 1896, 119).

The women’s sarongs were held in place by a narrow belt of palm strip (Meher: ehe; Oirata: bato), decorated with carved patterns that had been treated with lime to make them stand out against the yellow or dark palm wood. They wore bracelets decorated with coral and brass pins and hairpins decorated with feathers.

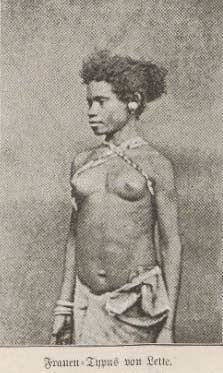

Woman on Kisar (Jacobsen 1896, 133)

The men wore a cotton loincloth and also had a patterned shawl called a sniker with ‘lively colours’, which was used after bathing. They also wore rings on their fingers and upper arms. At village feasts both sexes wore combs decorated with chicken feathers or goat hair.

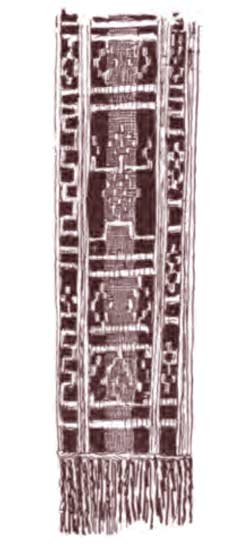

A man’s loincloth (Jacobsen 1896, 132)

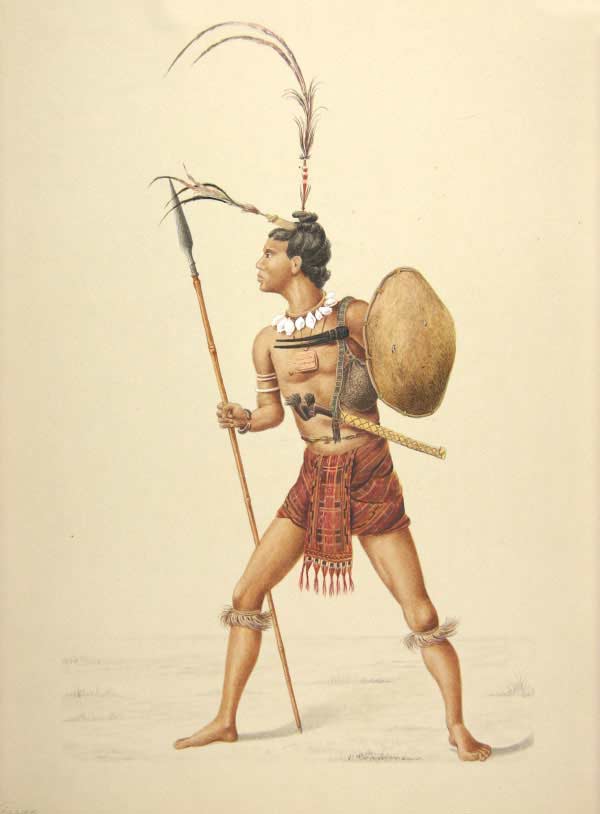

Jacobsen was also fortunate to encounter a warrior from Wonreli dressed in the customary loincloth, described as a product of the island’s ‘full blooming’ weaving culture. A corset-like cuirass of cowhide (ote or utte) protected his chest and he held a round leather shield. He was ‘armed to the teeth’ with a sword, war club, bow and arrow, iron-tipped lance and a short bamboo blowpipe for puffing lime powder into the eyes of his adversaries.

A Kisar warrior (Jacobsen 1896, 131)

A watercolour rendition of the same Kisar warrior by Ernst Krammerman

(Ethnologisches Museen der Staatlichen zu Berlin)

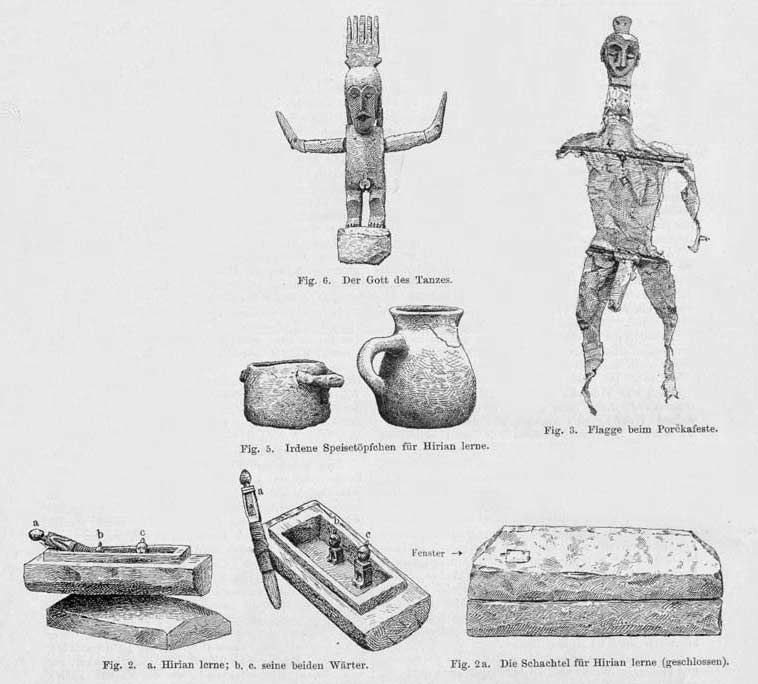

At the important purka feast, celebrated for several weeks in the autumn under the nuna or morinda tree, there was a mass sacrifice of pigs followed by singing and dancing throughout the day and night. Men and women danced separately and together, sometimes engaging in ‘sexual excesses’ on the dance arena. Throughout the festival two large flag-like fertility dolls – one male and one female - were hung from the tree. They had been sewn from cloth and stuffed with hay, and symbolised the union of the supreme deity, the old sun, opulere, and the earth, opunuse (Jacobsen 1896, 123). Jacobsen failed in his attempt to acquire them. Similar rituals were held on neighbouring Leti and Luang, termed porka and po’ora festivals respectively (Van Dijk and De Jong 1990). On Marsela in the Babar Archipelago, the ritual was known as the lulya festival.

A shaman with a drum and shoulder cloth at the purka feast on Kisar

(Jacobsen 1896, 126)

A cotton banner in the shape of a woman, attributed to Kisar

(Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

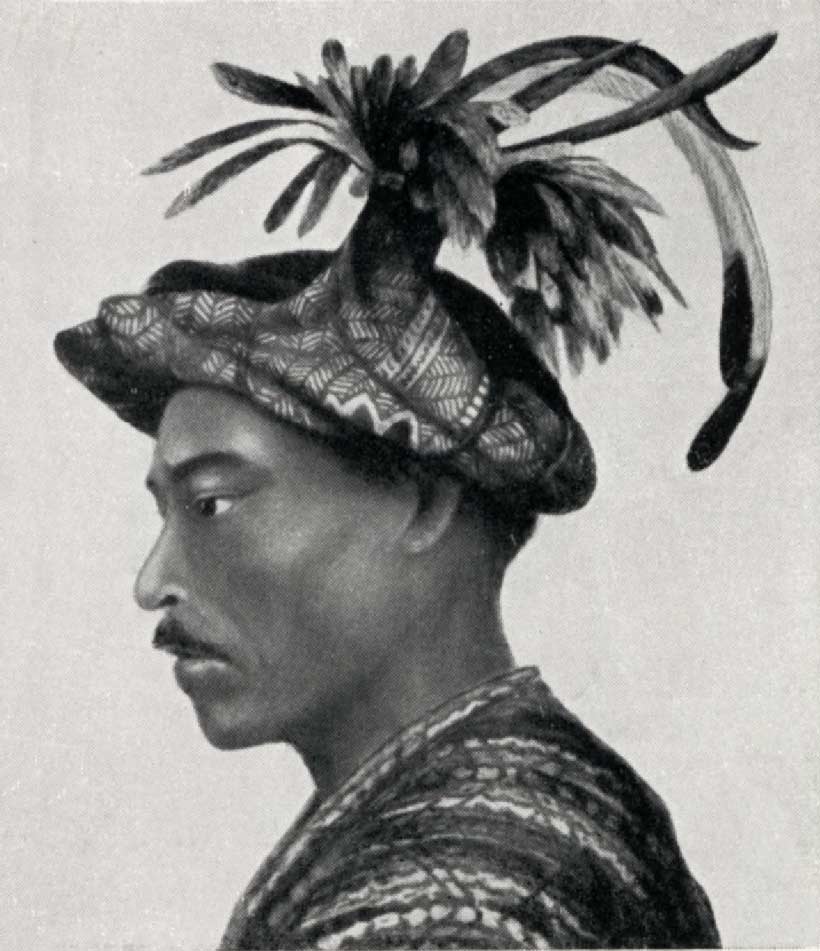

Jacobsen did succeed in acquiring a variety of different headdresses, which were only worn for the purka feast or during times of war (1896, 124-125). It seems that the more dramatic the headdress, the higher the status of the wearer. The most elaborate example was a semi-circular tower of wood with lontar palm leaves sewn to the front, which was then painted with dyes. A flag protruded from one side and a wooden doll depicting a warrior armed with a lance from the other. Many headdresses were based on a head-ring made from a crescent-shaped strip of wood tied at the back of the head with a cord. These were then decorated with feathers supported on stalks of horsehair or with perforated leaves. The Meher name for such a headdress was a manwu-lo-or. The Oirata had similar headdresses which went under a variety of names such as a dagku, reli-nulu, seb(e)raku or rapa-nulu.

A headdress collected by Jacobsen on Kisar in 1888 described as a manuwulu woor as opposed to a manwu-lo-or (Ethnologisches Museen der Staatlichen zu Berlin)

One year after his visit to the Netherlands Indies, Jacobsen published two photographs of women from the South Western Islands dressed in ceremonial costume. Unfortunately they were from Leti and Luang rather than from Kisar.

Photographs of women on the islands of Leti and Luang. (Jacobsen and Kuhne 1889)

A group of Kisar mestizos on Leti Island, photographed by E. van Lier around 1890

In 1891 Pastor Dr. J. G. de Vries travelled from Ambon to Kisar during a short tour of the South Western Islands on the governor's steamboat, the Havik (Pleyte 1896, 347-349). He found that the inhabitants of Kisar were occupied with tending their gardens and fields, weaving, and making gold and silver ornaments. During his visit he acquired several cultural artefacts for the ethnographic museum in Amsterdam, one of which was an anthropomorphic cloth flag that was raised at the entrance to the village during the purka festival.

Idols and a flag from the ceremonial village staging the 'idol festival', collected by de Vries in 1891 (Pleyte 1896)

Return to Top

Kisar Costume in the Early Twentieth Century

In 1897 the Raja of Kisar married a noble woman from Portuguese East Timor. After her arrival on Kisar she introduced a range of ‘intricate’ East Timorese motifs to other weavers among the nobility (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 232; Van Vuuren 2002, 113). These apparently included lozenge and hook motifs as well as images of men and animals. Of course this was simply an extension to an already wide range of motifs that must have been already present on the island, as evidenced by the illustrations of Riedel and Jacobsen. Many of these may have been introduced from East Timor as a result of long-term exchange between the two communities and the arrival of Fataluku-speaking immigrants from Loiquero in 1721.

The missionary Tammo Bezemer, who would later become an ethnographer, briefly visited Kisar at the turn of the century and found that the population was engaged in weaving (Bezemer 1906, 52). He briefly noted that among the mestizos (known locally as Waladas) the men wore a bodice and trousers, while the women wore a white kabaya, a sarong and slippers. The natives wore only a loincloth. Gerret Pieter Rouffaer also made a fleeting landing on Kisar during his voyage around eastern Indonesia in 1910 but left us no record of his visit.

Jasper and Pirngadie (1912, 274) identified three types of ikat fabric from Kisar, but left us with somewhat inadequate descriptions:

- a senikir, a man’s blanket made from two tubular cloths, decorated with broad pattern bands at each end. Its dimensions were about 1 el by 4 els (69cm by 276cm)

- a slèndang, a man's waist belt or strap for carrying a heavy load, which differed from a senikir by not having patterned end bands, and

- a tjawat or cawat, a man’s loincloth that was ‘worn in a special way’.

This latter item was a special high-status ikat loincloth, referred to as a warpitare, which required much more effort to make than an everyday loincloth. It was a luxury garment that could only be worn by prominent village or clan chiefs and on special festive occasions. It had a fringe and was worn loose over the right shoulder and wrapped around the middle of the body before hanging over the loins.

Jasper and Pirngadie did not describe the women’s two-panel tubeskirt apart from noting that it was short and narrow.

The German ethnographer and collector Wilhelm Müller-Wismar visited the South Western Islands during the Berlin-Indonesian expedition to the South Moluccas, which lasted from late 1912 until 1914. He was an obsessive collector, sometimes employing violence to obtian the objects he wanted (de Jong and van Dijk 2002, 250). During this expedition he acquired around 9,000 items, including twenty cotton textiles from Kisar, forty-five from Luang, but only four from Leti. Müller-Wismar visited Kisar in July and August 1914 and may have been more preoccupied with collecting than conducting serious ethnological research. Although Müller never returned to Germany (he caught typhoid and died on Java in 1916) his textiles did. They were donated to the city of Cologne and became part of the collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in 1924.

The twenty textiles collected from Kisar were markedly varied and included four belts, five waist belts, three loincloths, two shoulder cloths and five sarongs. They were mainly woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton. These were not new when collected in 1914, so have been assigned to either the late nineteenth century or to around 1900:

- the four belts were all woven in warp-faced complementary weave and ranged in length from 1 to 1½ metres,

- the five waist belts, three from Oirata and presumably two from the Meher community, were termed hita or hitilirrati. They were all decorated with warp ikat and had braided supplementary weft end bands and long fringes. Four were patterned with rows of hooked diamonds terminating with tumpal motifs,

- the three loincloths, one from Oirata and two from elsewhere, were termed niala, irä or warpitare. They were all decorated with narrow alternating bands of warp ikat and plain warp, two terminating with a broad band of brocade, the third terminating with a narrow strip of brocade and long fringes,

- the two shoulder cloths, or possibly loincloths, were woven from naturally white cotton and decorated with narrow warp stripes. They were finished with narrow transverse bands of supplementary weft and twisted fringes,

- the five two-panel tubeskirts, one from Oirata and four from elsewhere, were termed homnons.

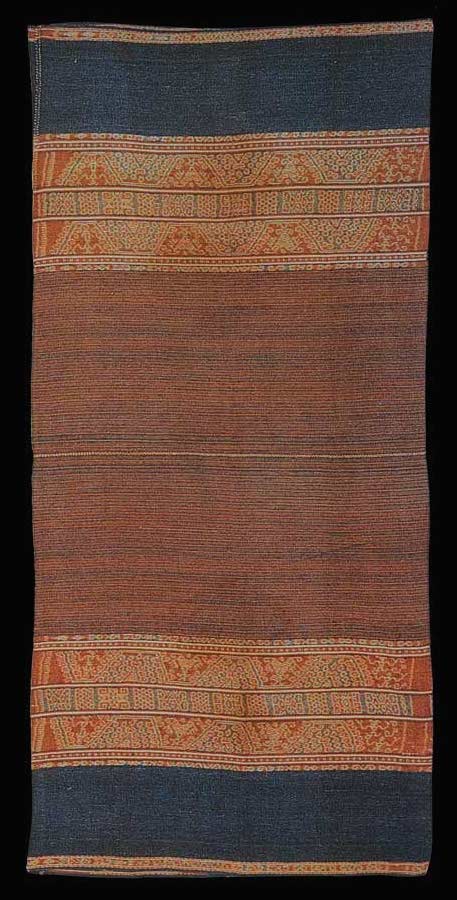

The ‘homnon‘ [sic] collected from Oirata has a centre of narrow rust, brown and blue warp stripes sandwiched between two broad, triple bands of warp ikat bordered by broad bands of plain indigo finished with narrow terminal bands of ikat. The triple band of ikat has a central band decorated with rectangular motifs, a few including the eight-pointed star reserved for the nobility, while the two outer bands were decorated with an angular wave pattern incorporating birds and human figures (Khan Majlis 1984, 160-161).

The nineteenth century lau from Oirata

Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne

Two of the remaining ‘homnons‘ have centre fields composed of narrow alternating bands of plain warp and warp ikat sandwiched between single wider ikat bands decorated with hooked diamonds and tumpal endings. The outer ends are finished with a wide band of plain indigo and a narrow terminal band of ikat. The final two ‘homnons‘ are more simple and decorated with nothing other than alternating narrow bands of plain warp and warp ikat.

Wijnand Nieuwenkamp visited Kisar briefly in 1918, arriving on 30 May and departing at dawn on 1 June. His only observation was that the natives did not have the uncivilised appearance of the Alorese and often wore a headdress made from a strip of palm leaf. He purchased several weavings and a hat but claimed that there was little else to collect. For reasons unexplained he concluded that prolonged contact with Europeans had harmed the artistic abilities of the islanders (Nieuwenkamp 1923).

Photographs from the 1920s show warrior dancers dressed in loincloths, with woven belts tied around their waists and feathered headdresses known as manuwalu woor (Siwalima 15.10.2016). The accompanying female dancers wear long-sleeved kebayas, long ikat sarongs with the tops folded down, multiple bracelets, beaded necklaces and tiaras, and imported shoulder cloths. The decoration of the sarongs appears to be very proscribed. They all have narrow bands of ikat terminating with a wider band of single geometric motifs (diamonds, stars, etc.) and a broad undecorated outer band. One has a beaded (siri?) bag decorated with diamond motifs hanging from her neck.

A warrior dance staged beside the old church at Lekloor in about 1920

(Collection of the Dutch ethnographer, Bertram Johannes Otto Schrieke)

Above and below: sarong-clad dancers at the same event, about 1920

(Collection of the Dutch ethnographer, Bertram Johannes Otto Schrieke)

The German tropical physician Ernst Rodenwaldt must have visted Kisar in about 1925 or 1926, spending a considerable time studying the mestizo minority. He noted that weaving was the island’s only notable industry, being founded on the cultivation of cotton and indigo, the former planted by slaves from Timor (1927, 5). However things were changing – he predicted that the local cotton and indigo would soon be replaced by imported Chinese and European yarns and synthetic aniline dyes. Indeed Chinese yarns, some pre-dyed, had been imported for over 50 years and more recently aniline dyes were starting to replace indigo. Young girls were all going to school and were no longer being taught natural dyeing. Even at that time, it was difficult to find a textile on Kisar which had not been spoilt by the inclusion of colourful European threads.

Rodenwaldt uncovered the fact that indigo cultivation had been introduced to the South Western Islands by the VOC in 1703 (See Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen 1912, 414). In that year two assistants, Zacharias Michielsz van Rijp and Hans Roelofs, were sent to Kisar to teach the local people how to make indigo dye in the Coromandel manner. In 1696 they had been working on cotton and indigo cultivation in Central Java, moving on to Sulawesi in 1702. Although indigo production never developed into a commercial enterprise, Rodenwaldt believed it led to the development of ‘the beautiful blue cloths of Kisar’.

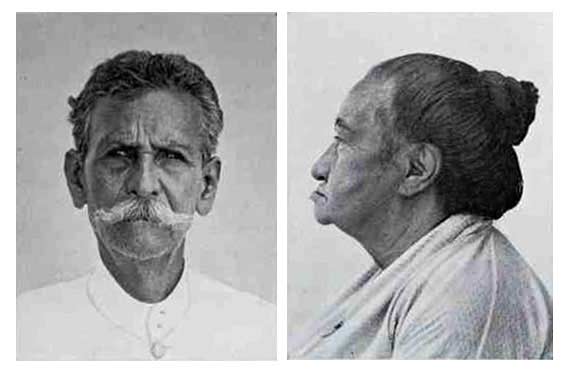

The mestizos had adopted the manners of the Kisarese in their clothing, food and customs, the women weaving sarongs and selendangs. Their snikirs or shawls were much sought after on mainland Timor. Rodenwaldt noted how the stylised motifs were formed by binding the warps with bast fibres, the weaving only taking place once the entire pattern had been completed. Yet the extent of ikat weaving was by no means as great as it had been in the past, it having already been abandoned by many of the mestizo families. At the time of his visit, 74-year-old Adriana Bakker was producing the very finest work. Rodenwaldt was pessimistic about the future of Kisar textiles, writing that it would not be long before they would only be found in museums (1927, 434).

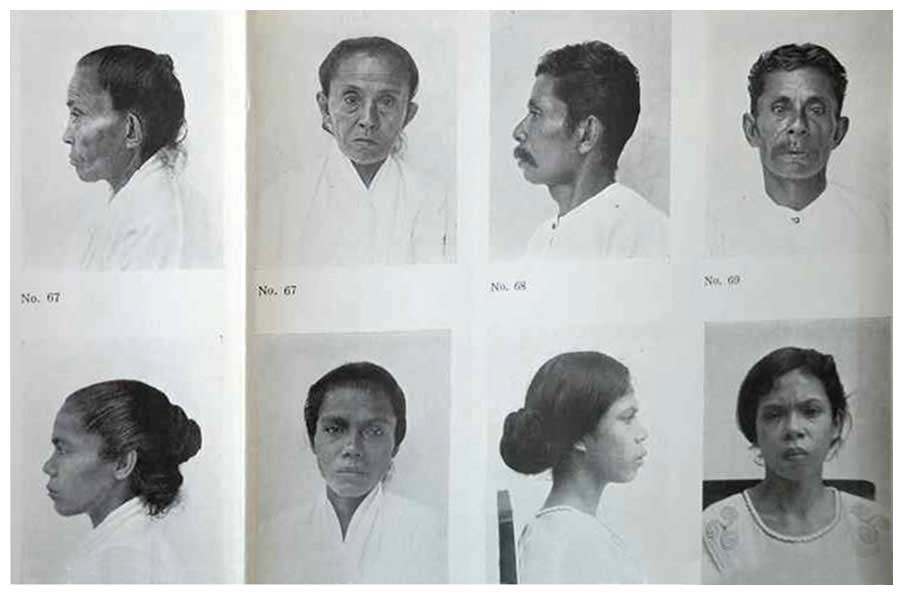

Regarding dress, the clothing of the mestizo women was neat, tidy and clean, unlike that of the native population. He put this down to their Dutch ancestry. Nevertheless it was only on solemn occasions that the men dressed in the European manner and the women in a sarong and kabaya (Rodenwaldt 1927, 401). Their finest shirts and blouses were partially illustrated in his head and shoulders portraits:

Above: Cornelius Caffin, the mestizo district head, and Adriana Bakker

Below: Some of the mestizo population of Kisar

(Rodenwaldt 1927)

Unfortunately Rodenwaldt left no record about the dress of the islands marna aristocracy or of the Raja of Kisar himself. The latter had inherited significant wealth in the form of gold crowns, masks, discs, moons, plates and daggers.

A selection from the gold pusaka or treasure of the Raja of Kisar, photographed by Ernst Rodenwaldt

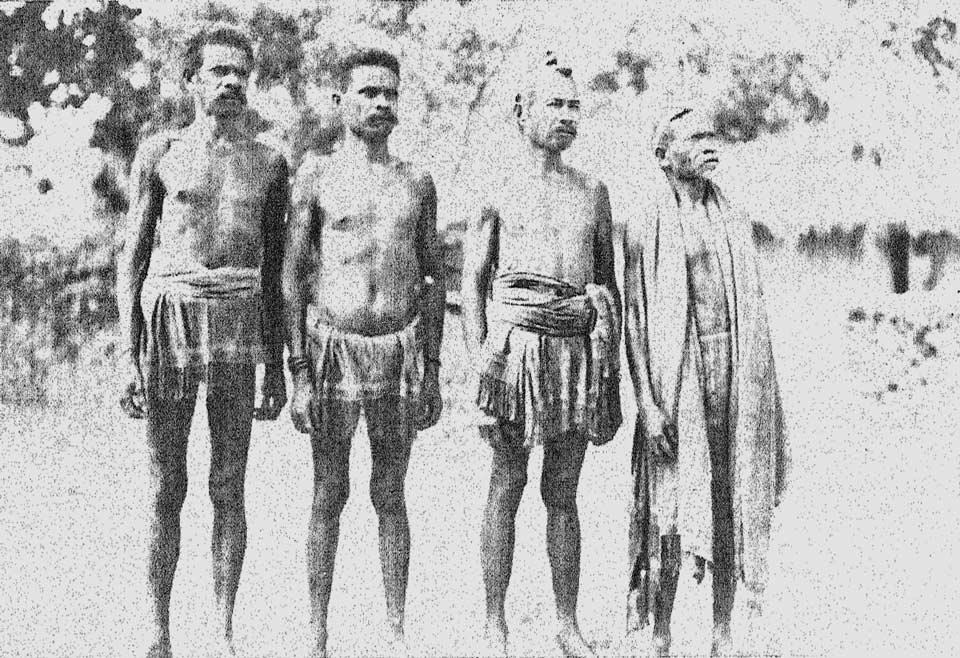

A staged 1926 photograph of four men standing in front of a picket fence on Kisar suggests they are nobles or clan leaders from the Meher community – three are wearing pectoral discs and the fourth a large crescent and two have smaller crescent-shaped forehead decorations. One of the men has a Gujarati patola hanging around his neck, another wears a light-coloured shoulder cloth. Three are wearing head cloths. They are all wearing an assortment of wide loincloths with long fringes, held in place by waist wrappers and a belt. The two broadest loincloths are around 40cm wide. The decoration of three of the loincloths is dramatic – the ends appear to have been embellished with wide transverse decorative bands edged by rows of nassa shells. The mystery is that they are worn in a very simple manner, not in the style of the warpitare ceremonial loincloth, which was flung over the right shoulder before being wrapped around the middle of the body with the other end hanging loosely over the loins (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 275-276).

Four men from Kisar, probably high-ranking nobles - the third man on the right wears a patola. From the Indisch Wetenschappelijk Instituut, dated 1926.

(Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence)

In 1929 the director of the Department of Ethnology of the Colonial Institute, Professor J.C. Eerde, visited Java to attend the Fourth Pacific Science Congress. During the conference dance performances were staged by various island groups in the great hall of the Batavian Zoo. During this event Eerde photographed two men from Kisar dressed in warrior's costumes.

Two Kisar warriors photographed at the Museum of the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences in Batavia by J. C. Eerde in May 1929

Three additional native Kisar clothing terms are listed in the 1932 Maluku catalogue of the Reichsmuseums von Ethnographie, Leiden (Juynboll 1932, 105-107). They consist of:

- a todone conical hat made from lontar palm leaf and bamboo,

- a rain rorau sleeveless rectangular barkcloth jacket, and

- a kornele, he loincloth made from barkcloth

No local terms were included for the locally woven sarongs or selendangs in the collection.

Male dancers photographed on Kisar at some time prior to 1936

(Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

Textile acquisitions from Kisar in 1933 listed in the 1934 yearbook of the Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (139-141) consisted of the following items, some of which were interpreted as tablecloths:

| Number | Local Name | Item | Description |

| 20544 | Sarong | Very long, thin two-panel sarong made from local yarns. Light red centre field with narrow stripes of warp ikat and wider bands of warp ikat at the top and bottom. | |

| 20545/73 | Sarong | Similar sarong to 20544. | |

| 20574 | Sarong | Similar sarong to 20544 but without the broader bands of warp ikat. | |

| 20583 | Textile | Textile like 20544 but not yet sewn into a sarong | |

| 20584 | Senikir | Two-panel blanket (slimoet) woven with native cotton and decorated with parallel stripes of warp ikat. | |

| 20585 | Senikir | Blanket | Blanket like 20584 but with slight differences. |

| 20586 | Warpitare | Loincloth | Belt woven from local cotton, beautifully decorated with very large white ‘putjuk rebung’ or bamboo shoot motifs on a blue ground. |

| 20587 | Tablecloth | Two-panel dark brown cotton cloth with black warp stripes. | |

| 20588 | Table runner | Cloth partly woven from native threads, decorated with multi-coloured ikat stripes with tumpal endings on a dark blue ground and with fringes at each end. | |

| 20588 | Table runner | Ikatted cotton cloth, possibly half a tablecloth. |

(Jaarboek, 1934, vol. 2, pp. 139-141)

At the beginning of 1934 Jan Petrus Benjamin de Josselin de Jong conducted five weeks of intensive fieldwork among the people of Oirata on Kisar, mainly focussing on their language and ethnography. However he did leave us some photographs of the leaders of the main Hano'o clan and a dictionary including some of the Oirata words for items of clothing. Unlike the Meher nobles shown above, the costume of the Hano'o nobles appears to be remarkably uniform.

Members of the Hanoo clan of the Oirata wearing ikatted waist and shoulder cloths

(Josselin de Jong 1937)

| English | Oirata |

| dress, clothing | hewete, also ulawara weltaru |

| dresses, clothing | hewe hewete |

| clothes, dresses | nainairi |

| clothes, clothing | paki |

| dress (clothes) | narasa |

| cloth | la’u |

| woven fabric | utunana or utnutan |

| woven fabric | ulawara weltaru |

| sarong | la’u |

| sarong (old-fashioned homemade) | laran la’u |

| woman’s sarong | tuhur la’u |

| woman’s jacket | rain |

| loincloth | mal or mala |

| loincloth | ulawara weltaru (lit. waist cover) |

| cape | loron |

| trousers | saholo |

| shroud | wetur kawas, also kawas or wetur |

| covering | kawar |

| towel | hantuku, sarapete |

Oirata clothing and textile terms listed by Josselin de Jong

More recently Engelenhoven (2010) published 73 Oirata terms, including mala for a loincloth, saholo for trousers, raini for a woman’s jacket and tutrulu for a hat.

Illustration of a man from Kisar with a chicken feather headdress, dated 1955-75. KITLV

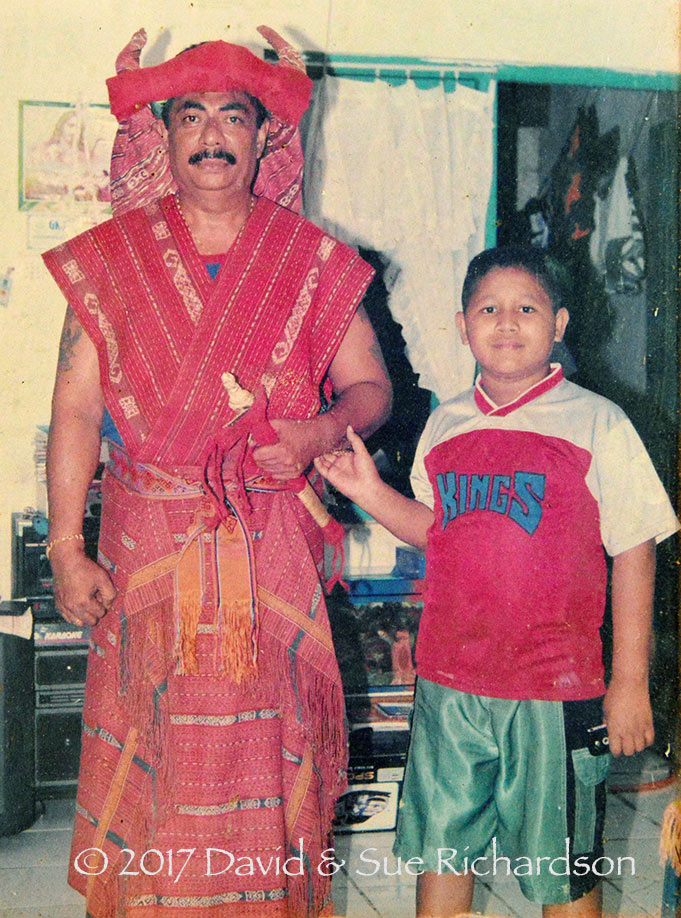

Despite the widespread adoption of synthetic dyes, traditional ceremonial costumes are still made and are still widely worn on Kisar Island for formal events.

The Twelfth Raja of Kisar, Wanamau Jhon Jesajas Bakker, with his young nephew Haimere Edwin Bakker, at Wonreli. He died in 2007

When Southwest Maluku (MBD) government officials and indigenous elders welcomed the Governor of Maluku, Said Assagaff, during a visit to Wonreli in 2016, he was honoured with gifts of a senikir blanket, a manuwulu woor headdress made of chicken feathers, a belt and a dagger – symbolizing greatness and protective power (tribun-maluku.com 15.10.16).

Said Assagaff is granted the official title Yalu Resi Lain Tulu, supreme leader of Kisar Island, in 2016 (Image courtsey of Tribun-Maluku.com)

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was first published on 5th October 2017.