Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Geography

The Pre- and Early History of the Kui Region

Majapahit Influence

The Founding of Kerajaan Kui

Narratives Describing the Introduction of Islam

A Limited History of Kerajaan Kui

The Ruling Dynasty of Kerajaan Kui

The Kui Language

Ethnography

The Dar or Lego-Lego Dance

Bibliography

Geography

The Kerajaan or Kingdom of Kui was a small domain founded around 500 years ago, that extended its influence over the south-western corner of Alor Island in eastern Indonesia. Under the Dutch it became a Rajadom (Radjaschap), with its traditional ruler allowed to retain his local powers and given the honorary title of Raja in return for accepting Dutch sovereignty and direction. In 1962, twelve years after Independence, Kerajaan Kui was officially dissolved as the Republic of Indonesia introduced a new system of democratic local government. Although the Raja of Kui lost his political authority, he still retained enormous respect and continues until this day to exert a strong influence over his former domain.

Kerajaan Kui was traditionally centred on the village of Lerabaing (sometimes written Lera Baing or Lerebain) located on the south-western coast of Alor, marked as Koei or Kui on many maps and sometimes historically referred to as Koewi. The name Lerabaing means the village of the king (Katubi 2013, 4). More accurately translated it means the place where the king resides, ler meaning king (Windschuttel and Shiohara 2017, 144) and baing meaning to wait or to stay. The influence of Lerabaing seems to have once extended across much of the south-western region of Alor Island.

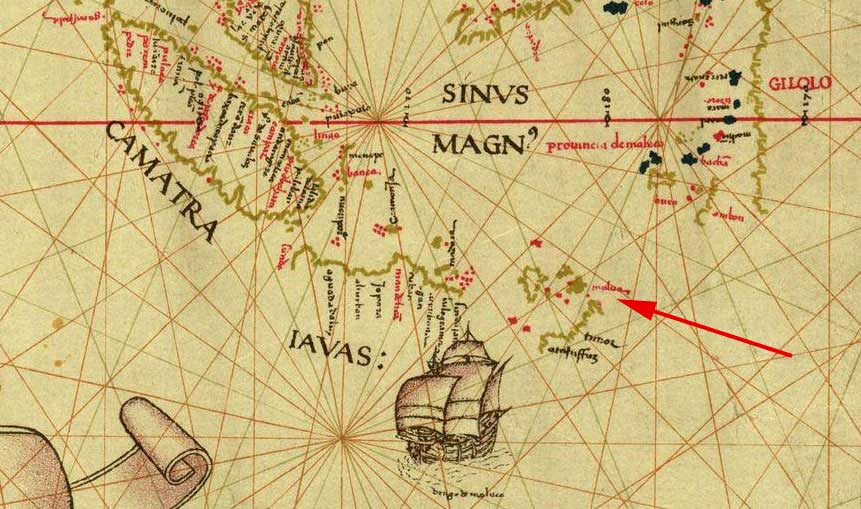

In the past Kui seems to have been referred to as Malua, a term used by the Portuguese, and listed as one of the five coastal domains linked by the Alor Strait joined in a loose confederation called the Galiyao Watan Lema. Malua was mentioned in a letter sent to the Sultan of Buton in 1682 (Dietrich 1984, 319). The term Malua was also applied to the whole island of Alor during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but was eventually superseded by the term Ombai (Hägerdal 2010, 221). According to van Lynden, Malua was a mountain community in the domain of Kui (1851, 329).

In a word list from Kerajaan Kui compiled in 1910, the term 'kui' is translated as dog (Anonymous 1914, 94). Local people still hold a belief that one of their ancestors was a dog which transformed itself into a kakak or older brother (Rodemeier 1993, 22).

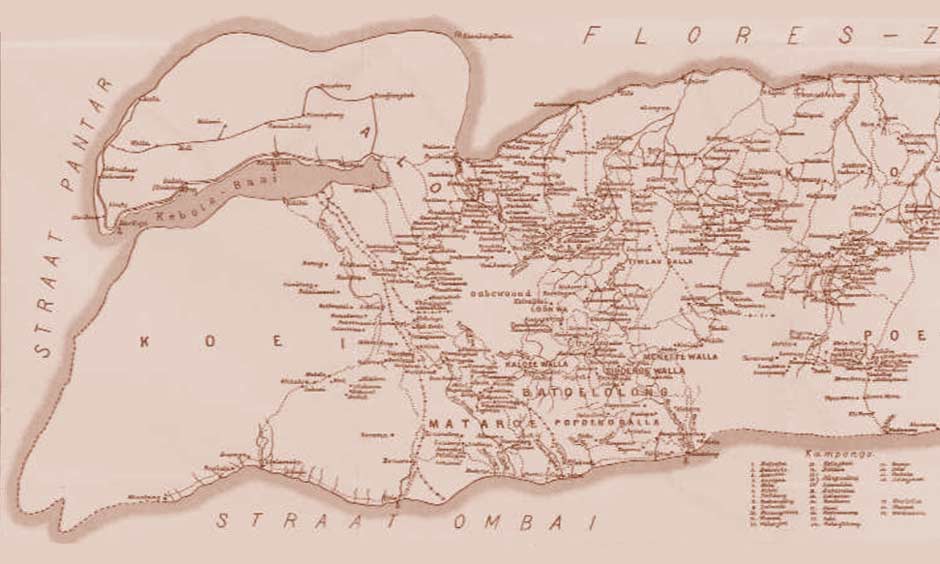

Map of south-western Alor Island and the Pantar Strait

(Image courtesy of the US Army, Washington, D. C., 1963)

According to the Dutch controleur of Alor, G. A. M. van Galen, the landschap (colonial region) of Kui in 1946 consisted of three kapitanships:

- Kui or Lerabaing, led by Kapitan Makunima Makunima from the kapitan family of Kui.

- Probur, led by Kapitan Thomas Loban, a son of the noble kepala besar of Mataraban kampong in Probur.

- Mataru, led by Kapitan Balsasar Sukurkoli from the kapitan family of Mataru.

The kapitans were local resident-administrators who reported to the Raja. Kapitan is a word of Portuguese origin derived from capitão (Ellen 1986, 52; Hägerdal 2010, 21).

Strangely van Galen omitted to include the northern centre of Moru, which had been settled by people from Kui since 1915, and had become the seat of the Raja of Kui in 1933.

The Rajadom of Kui encompassed four ethnic groups – the Abui (the largest ethnic group on Alor), the Klon, the Hamap and the Masin - which each had their own distinct language. As the Masin were the traditional rulers they were often referred to by the term Kui, which actually should only be used to describe the former Kerajaan or Kingdom and not one of its ethnic groups.

Today the Abui and the Klon make up the majority of the Christian community, accounting for 85-90% of the Kui population. The ruling Masin, who are mainly Muslim, make up only 10-15% of the population (Kinanggi 2018). Despite this there is complete religious harmony.

A 2011 survey of speakers of the Masin Lak language, the ethnic Kui, located only 833 individuals spread across three main regions ( 2011a, 124):

- Lerabaing-Wakapsir villages (20 houses or around 119 people),

- Bombaru and Buraga villages (80 families or around 315 people) and

- Kelurahan Moru and neighbouring Kikilai (78 houses or around 399 inhabitants)

This is far less than previous estimates. SIL International reported 4,242 Kui speakers in 2009 while Shiohara (2010, 179) reported a similar figure of around 4,000. It is likely that these numbers include significant numbers of Abui, Klon and Hamap.

Since independence and the reorganisation of local government in 1961, the Rajadom of Kui became absorbed within Kecamatan Alor Barat Daya, one of the seventeen kecamatan (sub-districts) of Alor Regency. Alor Barat Daya has one kelurahan (urban village) – Moru, the administrative centre of the kecamatan – and nineteen desa (rural villages), many composed of two or more dusun (hamlets). In 2017 the population of Alor Barat Daya was 23,000, 11.3% of the Alor Regency total.

Kerajaan Kui ruled over the southern desa of Alor Barat Daya and, since the 1930s, Moru. However the Masin themselves are confined to Moru and the two desas of Wakapsir and Tribur, where they live alongside Hamap, Klon and Abui people:

| Desa - 2017 | Administrative Centre | Dusun | Households | Population |

| Wakapsir | Sifala | 2 | 140 | 734 |

| Wakapsir Timur | Bomara | 2 | 189 | 613 |

| Tribur | Buraga | 3 | 442 | 2,142 |

| Moru | Moru | - | 561 | 2,463 |

| Total | 7 | 1,332 | 5,952 |

(Badan Pusat Statisik, Kabupaten Alor, 2018)

Topographically, Alor Barat Daya has a mountainous interior with deep steep-sided ravines, dominated by two upland areas that reach heights of 900m in the west and 1400m in the east. These two uninhabited highland areas are separated by the Buraga River Valley, which runs southwards through the plain of Buraga into Buraga Bay. The western coast is fringed with glorious sandy beaches.

The Topography of Kerajaan Kui and Alor Barat Daya

(Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Halmin Beach in Kerajaan Kui facing Treweng Island and southern Pantar

The rugged terrain and poor road system means that most of the southern villages are difficult to access. For example, the road from Moru to Buraga, which follows the Buraga Valley, crosses nine small stony riverbeds making overland access impossible during the rainy season. Even in the dry season it can only be traversed by a 4WD. There is also a southern coastal road running from Tanjung Margeta to Lerabaing, although the 9km-long stretch from Buraga to Lerabaing is in particularly bad condition, surfaced with broken coral rock.

The road to Buraga. Image courtesy of Mursanto

The main coastal plain in Alor Barat Daya lies on the south side of Kalabahi Bay opposite Kalabahi and is easily accessed by road from Kalabahi. It is the location of the municipality of Kelurahan Moru, a large semi-urban conurbation that includes the hamlet of Kikilae to its south, both being bordered by the Kikilae River in the east and the Moru River in the west. Kelurahan Moru is headed by a lurah, a civil servant directly responsible to the camat of Kecamatan Alor Barat Daya. Moru is also the current base of the Raja Muda of Kerajaan Kui, Nasarudin Kinanggi, and the location of his official keraton residence and reception room. The Raja Muda is married to a noblewoman from Jogyakarta.

The Kraton of the Raja Muda of Kerajaan Kui

Apparently Moru means 'the place reached by walking a long way' (Katubi 2005, 63). It derives from Morbelalan, Mor meaning 'place' and belalan meaning 'long journey', Moru being a long walk from the homeland of Lerabaing.

Moru offers a safe anchorage and a modern dock. It has two Protestant churches, Imanuel Habuka and Enkurio Ianabuk, and the large Catholic church of Saint Maria Fatima Kalonbuku. There are also three mosques – Nurul Huda, the largest on Jalan Banla Kinanggi, Nurul Yaqin, and Haqqul Yaqin, the smallest – and the Madrasah Ibtidaiyah (MI) Babul Jihad, equivalent to a primary school. The local office of PT. Cendana Indopearls manages the nearby pearl farm. Moru City was identified as an important local development centre in the 2013 Alor Regency regional plan.

The extended village of Buraga in Desa Tribur was initially settled by people who migrated from Lerabaing. It lies west of the mouth and flood plain of the Buraga River. It has a small fishing community and the al-Muhajirin mosque. A new solar power station built behind the village provides local electricity. Buraga has recently been designated by the local government as a fast-growing economic region.

The tiny isolated coastal hamlet of Lerabaing in Desa Wakapsir is built on a small plateau sandwiched between steep hills and the rocky coastline. The small Erbah River flows down along its eastern side. The hamlet is reached from the west by a poor rocky road from Sifala that skirts the coast, a 3 to 5 hour walk. Alternatively it takes 1½ hours from Buraga in a small boat. Further travel eastwards from Lerabaing is blocked by steep hills and cliffs plunging down from heights of more than 400m to the Savu Sea.

The topography of Lerabaing in Desa Wakapsir

(Image courtesy of Google Earth)

The small open-sided At-Taqwa Mosque, built on wooden stilts, is located on a rock outcrop beside a small beach overlooking the Savu Sea with the former Raja’s house located next door. The twenty residential houses are built on several terraces located north of the mosque. The hamlet is in a dilapidated condition, and there is no cell phone connection or any electricity so people use oil lamps for lighting. However they do have a diesel generator for special events.

The Al-Taqwa mosque at Lerabaing and the grave of Sultan Kimales Gogo

Desa Wakapsir and Desa Wakapsir Timur have been identified as having important deposits of gold, silver and lead as well as oil. They also have the potential for exploiting geothermal energy.

Work beginning on the Zanana Mine Project in Wakapsir Timur

In 2014 Kalabahi-based PT. Kuringgi Jaya Mining obtained exploration rights on a 206 hectare site at Zanana, some 9km northeast of Lerabaing in Desa Wakapsir Timur. This had led to protests by local mountain villagers. One of the positive features of such a development would be the construction of a good road from Buraga to Lerabaing.

Return to Top

The Pre- and Early History of the Kui Region

The first modern humans must have migrated through the Lesser Sunda Islands over 60,000 years ago. By then some had already established themselves in mainland Australia (Westaway et al 2017; Clarkson et al 2017). A few later 42,000-year-old remains of modern humans have been excavated from caves in East Timor (O’Connor 2007; O’Connor, Barham, Spriggs et al 2010; Malaspinas et al 2016).

Evidence of later human occupation in the Lerabaing coastal region of Alor comes from the discovery of human, shellfish and other remains at the two Tron Bon Lei rock shelters, located about 160 metres inland from the coastline at Lerabaing. Dated to the late Pleistocene and early Holocene (20,000 to 7,500 BP), they appear to contain the remains of mobile hunter-gatherers who subsisted by catching reef fish (Samper Carro, O’Connor et al 2016; O’Connor et al 2017; Samper Carro et al 2019). They produced circular fishhooks from seashells, which were undoubtedly highly valued. At one spot six shell fishhooks had been placed beside a human skull, apparently an early funeral ritual (Bellwood 2017). It may indicate that women on Alor were responsible for hook-and-line fishing and is the earliest example of a culture where fishing was seen as an important activity for both the living and the dead.

Circular shell fishhooks beside an adult female skull at Tron Bon Lei, Lerabaing

(Photographed by Sofia Samper Carro 2017, Creative Commons)

The widespread use of obsidian stone tools shows that these communities were already actively trading with other parts of the archipelago at this early time (Reepmeyer, O’Connor et al. 2016). Cranial measurements suggest they were the descendants of Melanesians who had crossed from the Sunda mainland into the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Later residents, possibly Austronesian, may have been responsible for the rock paintings of boats, anthropomorphic and other figures and geometric motifs in the Tron Bon Lei and Ba Lei caves at Lerabaing and the rock carvings in caves at Mainang and Mademang (Laporan Linus Kia 2018). An analysis of the paintings showed that Tron Bon Lei had six different types of rock art, while Ba Lei had ten (Pratiwi Budi Amani 2016). Another residential cave has been located at Makpan between Halmin and Ling ’Al in Desa Halerman on the western tip of Alor Barat Daya.

Archaeologists from Balai Arkeologi, Bali, working at a cave site in Alor Barat Daya

Return to Top

Majapahit Influence

In 1357 Gajah Mada, the grand-vizir of the Hindu Majapahit state of Eastern Java, led a powerful naval expedition eastwards, subjugating much of Nusantara (Barnes 1982, 410). This most likely included some of the settlements in and close to the Alor Strait. The Nāgara-Kěrtāgama chronicle written on Bali in 1365, lists Galiyao, a term that referred to Pantar and possibly included the domains on the opposite coast of Alor, as one of the Majapahit tributaries (Pigeaud 1960, III, 17; Pigeaud 1962, IV, 34).

Carving of a Javanese sail boat with outriggers and a tripod mast, Borobodur, ninth century CE

An oral narrative from Pantar describes how Javanese attackers later destroyed the kingdom of Munaseli on Tanjung Muna, Pantar’s northernmost cape (Rodemeier 2006, 268-272). The refugees from Munaseli fled to various locations on Alor and even to Lembata. Apparently some settled in the villages of Probur, Sendak and Mataru in the domain of Kui.

There does seem to have been a conflict at Munaseli, but not involving the Majapahit Javanese. During or before the 14th century, Lamaholot speakers arrived on the coast of Pantar from the west – possibly from the Kédang region of Lembata Island (Klamer 2012, 102). It seems probable that the above legend reflects a war between these newly settled immigrants or with the endemic natives. In the early 15th century at least one group fled from Pantar to settle at Alor Besar on the opposite side of the Pantar Strait in western Alor. Some may have continued as far as eastern Kolana (Rodemeier 2006, 69). Others may have settled at Kedang and Hadekewa in Waienga Bay on Lembata (Barnes 2001, 279). It is therefore quite possible that some landed on the coast of Kui.

Another oral narrative proposes that Kui was one of five domains (known as the Galiyao Watan Lema – the five shores or coastal domains of Galiyao) founded by the five sons of the Majapahit prince, Mau Wolang or Mau Jawa (Gomang 1993, 28). Lau Mau Wolang is named as the founder and ruler of Kui. His brother Tulimau Wolang founded Alor on Alor Island, while the other three founded Pandai, Baranusa and Blagar on Pantar Island. A similar tale claims the father of the five sons was a Raja Majapahit, who had travelled from Java to the ‘island of Barnusa’ or Pantar (Dietrich 1984).

This is clearly only a story. The Galiyao Watan Lema alliance was actually formed from pre-existing Islamic coastal states, as we shall see later.Return to Top

The Founding of Kerajaan Kui

The Masin believe that the ruling dynasty of Kerajaan Kui was founded at Lerabaing by the chief of immigrants from Soe and Ende on Flores Island. A convoluted oral narrative describes their perilous voyage along the southern coasts of Flores, Solor, Lembata and Pantar, then north through the Alor Strait, into and out of Kalabahi Bay and then along much of the north coast of Alor. This was followed by a walk across the rugged interior of the island to reach the southern coast, followed by another short voyage westwards. On their arrival they became embroiled in an ongoing tribal dispute, which they were able to resolve.

Various aspects of the story have been published – initially by Haan in 1995 and later by Yordan Libang, a government official who lives in Moru, in 1999. A later version was given by Thung Ju Lan Katubi (2005, 59-65), while Emilie Wellfelt has published two more, one written by Banla Kinanggi, the last true Raja of Kui, and another collected from Lerabaing village (2016, 256-267).

Summarising the combined versions, it seems that along with others a certain Maleikili (or Malai Kil)and his elder brother Karkili (or Kar Kil) left Ende in a kora-kora or perahu called Marikawal. They may have stopped on the south coast of Lembata before entering the Alor Strait, making landfall in the west coast of Alor, at Wolan and Matap, before entering Kalabahi Bay to stop close to Moru. At each stop they encountered various landowners. At Moru, Karkili left the boat, befriended a dog, and crossed the mountains on foot to Buraga on the south coast. Maleikili crossed to Cape Sembilan on the northern coast of the bay just west of modern day Kalabahi, seeking to take control of some land. There he was confronted by an old man called Silu, who he killed and decapitated, placing his head in the boat. One infers that this was hostile territory.

The route of Maleikili

(Based on Wellfelt 2016, ill. 29)

Maleikili returned to the Alor Strait, passing Alor Besar, Kokar and Tanjung Sika, and continuing eastwards as far as Cape Babi, where the Marikawal was damaged or shipwrecked. Maleikili and his followers then walked inland crossing the central mountain range and eventually reaching the south coast near the village of Kiraman in Batulolong. Here Maleikili built another smaller kora-kora, which he also named Marikawal. Now sailing west they finally landed at Alat Akan (Black Sands) beach, where Karkili was waiting. Katubi interprets this as the long sandy beach at Cape Sibelah, just west of Lerabaing (Katubi 2011b).

After they arrived they found that the local tribes had been at war with each other. There were three main groups: the Abelwas living in Peraman, the Kuiwas or Kuyas living in Kuiman and the Murwas and Mayang living in caves along the shore at the place that would later be named Lerabaing. Although the Muwas and Mayang were the landowners, they faced attacks by the tribes from Peraman and Kuiman. A plan was hatched for the Murwas, Abelwas and the immigrants from Ende to fight against the Kuiwas and together they attacked the fortified village of the Kuiwas at night and defeated them. The warring tribes agreed to a treaty and joined together to form a tribal confederation. The Murwas and Mayang decided to offer Maleikili and his supporters from Ende the role of Tana Misa or Tena Mesa, those who reside (misa means to sit) in the village and rule (Katubi 2005, 62, 65 and 118). Maleikili, renamed Maleisoma, became their tribal chief (Haan 1995).

The reason for selecting Maleikili was that as an outsider he was seen as being independent and therefore the only person who could unite the previously warring tribes. It was vital that as their newly appointed leader he maintained his neutrality by avoiding any involvement in ongoing local conflicts. Maleikili and his followers from Ende therefore founded the village of Lerabaing and formed suku Ler Araman, the clan of the king. The Murwas and the Mayang agreed to become the tribal confederation's warriors and the king's bodyguards, forming the clan or suku Kaletowas. The Kuiwas and Lonwas became the king’s spokespersons and formed suku Kui Lelang (also known as the clan of the kapitans), while the Abelwas and Magalwas became responsible for religious affairs and formed suku Malangkabat.

Maleikili is the first chief to be listed as the head of the dynasty of Kui reported by van Galen (1946, 33). He is clearly an example of a ‘Stranger King’, the founder of a ruling dynasty who despite being a foreign immigrant is nevertheless freely chosen by the indigenous population. This is a surprisingly common phenomenon in the eastern Lesser Sunda Islands, particularly those regions that came under Portuguese influence (Lewis 2010, 197). On the assumption that ‘Malei’ refers to a person who is a Malay-speaker, Wellfelt suggests that a leader who was fluent in the regional lingua franca, was a good military strategist, and also a boatbuilder may have been seen as important attributes by the Murwas (2016, 267).

Maleikili probably arrived at some time during or before the mid 1500s, since his descendant, the fourth chief Kinanggi Atamalei, was ruling in either the late 1500s or early 1600s – see below. Maleikili’s arrival would have probably been around the time Portuguese Dominicans founded their missionary station on Ende Island in 1561.

Interestingly when Ernst Vatter asked some of the Klon-speaking residents of Kui about their origins in 1929, they too believed that some of their population had migrated there from Ende on Flores (1932, 242).

A recent limited archaeological study of the hamlet of Lerabaing has identified several phases of construction dating from before the introduction of Islam in the seventeenth century (Kartika Bunga 2016). These consist of stone circles, a stone embankment and a tomb, said to be that of Tar Soma Kinanggi, supposedly the fifth king of the Kerajaan of Kui. Unfortunately no person of that name appears on the list of rulers published by van Galen. However the current Raja of Kui has informed us that chief Tar Soma was the third not the fifth king of Kui (Kinanggi 2018). Possibly he was therefore the same person as chief Gaw Amalei listed by van Galen, the last animist leader of Kui. Fragments of a boat at Lerabaing are said to be from the vessel used by the two ancestors who founded the village. Fragments of ceramics also found in the village appear to be of European origin (Nandiwardhana 2017).

Apparently chief Tar Soma was involved in a fight between the Kerajaans Kui and Alor Besar and sought help from warriors from Timor. The Timorese reinforcements landed at Serani beach near Hirang on the west coast of southwest Alor (Kinanggi 2018).

Return to Top

Narratives Describing the Introduction of Islam

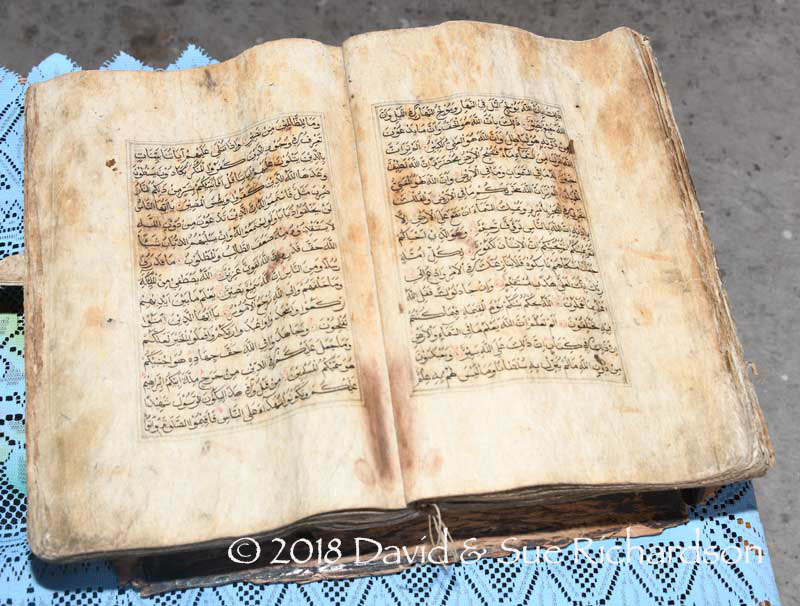

Oral narratives collected in Lerabaing as well as the Muslim villages of Alor Besar in Alor Barat Laut and Bakalang, Pandai and Baranusa on Pantar explain how Islam was first introduced into these centres by a small group of religious scholars, all brothers, who arrived by sea aboard the sailboat Tuma Ninah from Ternate Island in Maluku some 14 to 17 generations ago (Gomang 1993, 44; Rodemeier 2010, 28). Assuming 25 years for one generation, this would place their date of arrival between the late sixteenth and the late seventeenth century, after the arrival of the Portuguese. Evidence supporting this story is provided by an old Arabic Qur’an, which is hand-written on bark paper, and a circumcision knife, both kept in a house at Alor Besar.

The wood bark Qur'an, said to have been brought to Alor Besar by Iang Gogo from Ternate, Maluku

The promulgation of Islam by the Sultanate of Ternate seems to have been motivated by the assassination of Sultan Khairun in 1570 on the orders of a local Portuguese captain (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 19; Subrahmanyam 2012, 144). His son, Sultan Babullah, responded by driving the Portuguese from the island, enhancing his status in the process. This then led to an increased effort to spread Islam more widely throughout Maluku and beyond, extending as far as some of the coastal kingdoms of Sulawesi.

Some time after the enclaves of Kui and Alor Besar on Alor Island and Pandai, Baranusa and Blagar on Pantar Island converted to Islam, they appear to have formed a loose alliance of brotherhood named the Galiyao Watan Lema – the five shores of Galiyao, with Pandai at its head. An oral history indicates this occurred during the reign of Pui or Pa Soma (Gomang 1993, 85). Coincidentally, at some time prior to 1590, a similar political alliance had been formed in the nearby Solor Archipelago between five further coastal Muslim domains, which was known as the Solor Watan Lema. The two separate alliances eventually joined in a coalition known as the Sepulu Pandai or Ten Shores (Gomang 1993, 88-89; Hägerdal 2012, 38). This appears to have taken place while the tyrannical António d’Andria was commander of the Portuguese fort on Solor in the very late 1500s (Gomang 1993, 89). Gomang suggests the motivation was to form an axis of coastal Muslims (known locally as the Paji) to wage war against the Demon, local inland or ‘mountain’ people (Gomang 2006, 485).

Because the Galiyao Watan Lema was allied to Ternate, its troops assisted Ternate in its support of the Dutch fleet commanded by Apollonius Schotte that successfully laid siege to the Portuguese fort on Solor for three months in early 1613 (Gomang 1993, 98). After capturing the fort, Schotte reported that both Ende and Galiyao had risen up against the Portuguese and declared themselves subject to the king of Ternate, implying alliance to the Dutch (Tiele 1886, I, 109). Regarding timing, this implies that the initial Islamisation of Kui took place sometime after 1570 and before 1613. This is consistent with Gomang, who states that according to local oral history the Muslim clerics arrived in the late sixteenth century (1993, 98). However some residents of Lerabaing claim that they arrived a little later in 1625, after the siege of Solor, and that the local At-Taqwa mosque was built in 1633. Frustratingly, the oral narratives do not always align with the historical record.

The number of Muslim clerics who arrived from Ternate varies in the respective narratives. Two reports mention four:

- Iyang Gogo, Kima Lasi (or Kimales) Gogo, Selema (Boi) Gogo and Si Gogo (Gomang 1993, 98)

- Si Gógo, Sulema Gógo, Kima Lásang and Makáni (Rodemeier 2006, 218 and 227)

Rodemeier later lists seven: Si Gogo, Sulema Gogo, Kimales Gogo (aka Boi Gogo or Kimalasang), Makani, I’ang Gogo, Ilyius Gogo and Djao Gogo, the additional names being given in 1984 by Saleh Panggo Gogo, the custodian of the old Qur’an at Alor Besar (2010, 28).

It seems that one cleric settled in each enclave – Si Gogo at Pandai and Blagar, Selema Gogo at Baranusa, Iyang Gogo at Alor Besar and Kimales Gogo at Lerabaing. Each village head was given a Qur’an and a circumcision knife, with one of the scholars remaining in each village while the others journeyed on to the next. Each Muslim scholar married a local woman thereby founding a local dynasty of religious leaders (Rodemeier 2010, 28).

At Lerabaing, Kimales Gogo converted the animist chief Kinanggi Atamalai to Islam, after which he began to spread the new faith throughout his Kingdom of Kui, founding the Al-Taqwa mosque beside his home. Following the arrival of Islam, local people began to be buried in a north-south orientation. Local villagers claim that Kinanggi Atamalai reigned from 1619 to 1638 but the source for these dates is unclear. The tombs of King Kinanggi Atamalai and Sultan Kimales Gogo are claimed to be at the rear and in the front yard of the mosque. The additional tombs of the warrior leaders Gestar Soma and Samala are located on the seafront, while that of Takal Makain is in the northwest corner of the mosque.

Return to Top

A Limited History of Kerajaan Kui

The early Portuguese were well aware of Alor. In 1511 the first Portuguese seafarers sailed along the north coast of Pantar and Alor before navigating north eastwards towards the Bandas – the chronicler António Galvão, who died in 1557, recorded that from Java (Jaoa) they sailed to Bali (Balle), Lombok (Anjano), Sumbawa (Simbaba), Solor, Pantar (o Galoa), Alor (Mauluoa), Wetar (Vitara), Hatta or Rozengain in the Bandas (Rosolanguim) and Aru (Arus) (Galvão 1731, 6, 44).

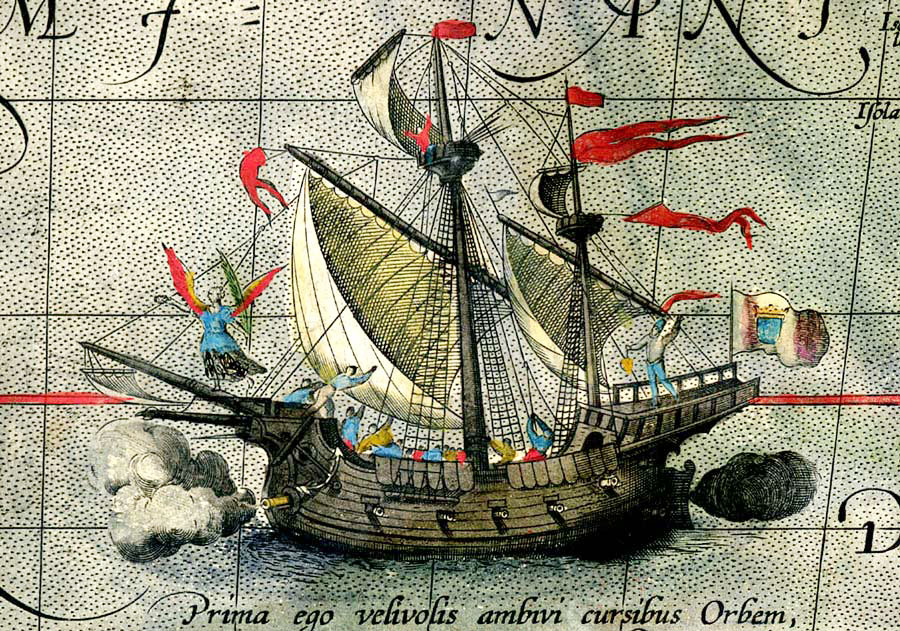

Magellan’s Victoria as depicted on the 1589 map Maris Pacifici by Abraham Ortelius

A decade later on either 8 or 10 January 1522, Magellan’s ship the Victoria, captained by Juan Sebastián de Elcano, sought refuge on ‘lofty’ Alor following a storm (Pigafetta 1906, 153 and note 569). Le Roux proposes that the Victoria’s two Ternate pilots sailed eastwards along the south coast of Alor, passing Kui, before anchoring on the east coast of Alor and re-caulking the hull (Le Roux 1929, 56). On 25 January they sailed south to Timor (Pigafetta 1906, 161).

Malua (Alor) is marked on the worldwide Padrón Real map of Portuguese cartographer Diego Ribiero, dated 1529

It was around that time that Islam may have been brought to Solor and Adonara by clerics from Java (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 77). Half a century later, in 1562, Catholic Portuguese missionaries from the Dominican Order erected a fort on Solor Island and converted some of the local community (Barnes 1987, 209-210). However the local coastal Muslims on Solor, known as the Paji, viewed them with suspicion. Because Solor was so infertile, the Portuguese were forced to obtain their provisions by importing them from nearby Ende, Sikka and Pagua on the south coast of Flores and from Galiyao (Tiele 1886, 89). This seems to have created a weak alliance between Galiyao and the Portuguese. As suggested above, the coastal states of Pantar (Galiyao) and Alor (Malua) were not Muslim at that time, only adopting Islam around the late 1500s or early 1600s.

When the Dutch commander Apollonius Schotte laid siege to the Portuguese fort on Solor in 1613, assisted by troops from Ternate, the Galiyao Watan Lema was still nominally allied to Portugal. After capturing the fort, Schotte reported that both Ende and Galiyao had risen up against the Portuguese and declared themselves subject to the king of Ternate, implying alliance to the Dutch (Tiele 1886, 109). That Galiyao had switched its loyalties from the Portuguese to the powerful Sultanate of Ternate in Maluku may have been political expediency. Despite this, the coastal Rajas of Alor and Pantar appear to have maintained a loose loyalty to the Portuguese for the following two centuries. A Portuguese manuscript dated 1624-1625 mentions that Galiyao (Pantar and west Alor), along with Levotolo (Ilé Api) and Queidao (Kédang) on Lembata, were inhabited by both pagans and Muslims (Barnes 1982, 408).

Like the Portuguese, the Dutch VOC on Solor may have obtained some provisions from Pantar and Alor, using local Islamic seafarers as intermediaries. In 1657 the VOC relocated their base of operations from Fort Henricus on Solor to Fort Concordia in the Bay of Kupang on Timor. Although the Solorese showed much displeasure, the Dutch maintained good relations with the local ruler of Lamakera who assisted them in their trade with Pantar and Alor (Hägerdal 2012, 237).

If the Solor Watan Lema and the Galiyao Watan Lema, including Kui, had broken with the Portuguese and loosely allied themselves to the VOC, this may explain their appeal to the Sultan of Buton in 1682 (Dietrich 1984, 319). They appealed for help against the Portuguese because they had received no help from the Dutch (Rodemeier 253). Their message was then referred onward to the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. It seems that neither the Butonese or the Dutch responded to this appeal.

In the following year the Sultan of Ternate concluded a treaty with the VOC whereby he renounced all claims on the Solor and Alor islands (Le Roux 1929, 14). Around this time, traders from the western archipelago and Makassar were appearing regularly in the main eastern Indonesian markets, located in the ports of Solor, Alor, and Aru (Rouffaer 1923/24, 206; Noorduyn 1983, 103–4).

The lack of Dutch interest in Alor seems to have encouraged the Portuguese mestizo leader on Timor, Domingus da Costa the chief of the Topasses, to exploit the situation. In 1717 he sent a small expeditionary force to Pandai on Pantar, the head of the Galiyao Watan Lema, to establish a small fortress (Hägerdal 2010b, 232). A little later they moved across to Kokar, just north of Alor Besar. The Dutch VOC responded in 1719 by sending one of its officials to Alor, reminding the Topass captain that Alor was within the Company’s orbit. It seems the Portuguese returned to Lifao.

The Dutch appear to have taken no further interest in western Alor but may have traded indirectly. During the 1730s, 1740s and 1750s small local prahus, often crewed by Solorese sailors, plied the route between Alor and Kupang (Hägerdal 2010b, 233). This seems to have dwindled in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was conflict between Kui and the neighbouring Klon (Kelong) and Mataru, with Kui eventually subordinating them both (Gomang 1993, 3).

During the second half of the 18th century the Dutch VOC was in severe difficulties and ceased to have any significant influence beyond Kupang. In 1785 the governor of the Banda Islands complained to Batavia that marauders from Pantar were harassing Wetar Island (Hägerdal 2010b, 235; Hägerdal 2012, 245). The complaint was forwarded to Kupang, where the VOC said that Alor was beyond its jurisdiction and that it did not have the capability to intervene. Following the dissolution of the VOC in 1799, Alor and Pantar became a diplomatic no-man’s-land – although the two colonial powers still laid theoretical claim to the region, neither had the incentive or means to take effective control.

The Dutch hold over the East Indies loosened further during the French Revolutionary and Napoleon Wars. The British occupied Kupang in 1812 and maintained control until 1816, providing a window for the Portuguese Governor, Victorino Freire da Cuñha Gusmao, based in Dili, East Timor, to regain influence in the region, possibly invoking the threat of military action (Hägerdal 2010b, note 61). In 1814 Raja Manhola of Pandai and Raja Kawiha Naha of Alor Besar responded by requesting to be placed back under Portuguese authority (Rodemeier 2006, 78). It is quite possible that the Raja of Kui followed suit. The Portuguese Governor endorsed this request and sent flags to confirm the new suzerainty.

The Dutch returned in 1816 and placed a posthouder on Pantar in 1820 (Hägerdal 2010a, 18). In that same year the Sepulu Pandai or Ten Shores composed of the ten domains of Galiyao Watan Lema and Solor Watan Lema finally disintegrated as a result of internal differences (Hägerdal 2012, 38 and 245 note 95). One reason may have been a division in loyalties between Holland and Portugal.

According to a Dutch letter of 1851, the Kerajaan of Kui had been flying the Portuguese flag since 1844, implying loyalty to Portuguese Timor (Van Lynden 1851, 334). However it is possible that this loyalty extended back earlier, possibly to 1814.

When the Dutch commissioner, Emanuel Francis, visited Kupang in 1831/32 he recorded a list of the local domains recognised at that time. The list for Alor included Kui, Kelong (Klon) and Hamapu (Hamap) (Hägerdal 2010b, 236-237).

In 1846 the three coastal Rajas of Kui, Blagar, and Beno reacted to continued aggression from the surrounding mountain dwellers and sought help from the princedom of Oecussi on Timor, which was allied to the black Portuguese or Topasses (Hägerdal 2010b, 240). At the same time two other Rajas, of Alor Besar and Baranusa, called for assistance from the Timorese princedom of Amfoan for the same reasons. However Amfoan was allied to the Dutch. After arriving on Alor the detachments from Oecussi and Amfoan encountered and confronted each other, with the former taking fright and sailing back to Timor, while the warriors of Amfoan proceeding to wage war on the mountain people.

One consequence of this activity was that Oecussi informed the Portuguese governor of Dili that Kui fell within the Portuguese enclave of Liquiçá in East Timor. The Dutch reminded Dili in 1847 that Kui fell under the authority of Dutch Lamakera on Solor Island. This, along with other territorial disputes, led to discussions between the Dutch and Portuguese that in 1851 resulted in a clearer differentiation between their respective colonial territories. The new governor of Dili, José Lopes de Lima, ceded the islands north of Timor to the Dutch, in return for the enclave of Oecussi and Maubara and Atauru Island in East Timor. Because the islands ceded to Holland were larger than the territories ceded to Portugal, the Dutch would make a payment of 200,000 florins (de Sousa Saidanha 1994, 38-39).

In 1851 van Lynden reported that the term Maloewa (Malua) not only applied to the whole of Alor Island but also to the natives of Kui, specifically those that lived in the mountains (1851, 329). These were presumably the Kuyas referred to in the local oral narratives. More than one hundred prahus a year were visiting Alor, the Butonese buying rice and corn and the Bugis and Makassarese beeswax (1851, 333). Some of the latter probably came from Kui. Kerajaan Kui was one of the locations on Alor that exported bird’s nests. It was also a producer of pottery (1851, 332). It seems that the Raja of Kui also owned boats that traded with Kupang on Timor and with the Solor Archipelago (Wellfelt cited by Schapper and Klamer 2017, 308).

On 6 August 1851 Alor came entirely under Dutch rule (Van Galen 1946, 21). However the formal treaty of demarcation between the colonial territories of Holland and Portugal was not finalised until 1854 and was only ratified in the 1859 Treaty of Lisbon. Despite this the Dutch responded quickly to establish a presence on Alor, installing the posthouder Johan Hendrik van Nimwegen at Alor Kecil at the mouth of Kalabahi Bay in 1852 (Almanak van Nederlandsch-Indië 1852). The transfer of Alor from Portugal to Holland was met with bitterness among some of the island’s local coastal elite.

As with several other local native leaders, the Muslim chief of Kui, Gesi (presumably Banla Kinanggi), refused to switch loyalties and hoist the Dutch tricolour. In January 1855 the Dutch steam warship Vesuvius appeared in the roadstead of Kui and reduced the village to rubble with its guns, although it seems that the mosque survived (Hägerdal 2010, 18-19). However this date is suspect since the Vesuvius was only launched in 1858. The Dutch deposed Raja Gesi and replaced him with his more malleable son, Pui Soma or Pasoma Gaw Amalei. Following the bombardment, many residents moved away from Lerabaing, some settling in Buraga and some establishing new villages.

The Royal Netherlands Navy steam sloop Vesuvius, launched in 1858 and armed with 30-pounder and 12-pounder guns

During the 1850s the Dutch split Alor Island into four self-governing regions or zelfbesturende landschappen. Later on this was changed to six – Alor, Kui, Mataru, Pureman, Batulolong and Kolana (Hägerdal 2010a, 20). In return for loyalty to Holland the chief of each landschap became a Raja and was given powers over his domain, including its non-Islamic mountain villages - powers that they lacked the ability to impose. Pui Soma or Pasoma was appointed the first Raja of Kui, supported by a single Kapitan, both based at Lerabaing.

In 1860, one year after the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Dutch established a small military post on Alor headed by a Lieutenant Pelt aimed at controlling the slave trade (Dalen 1928a, 159 and 219). Yet the Portuguese flags owned by some of the coastal Rajas – a symbol of their loyalty to Portugal – were never collected by the Dutch or replaced with the tricolour (Hägerdal 2010a, 19).

The Dutch found it impossible to impose their Pax Neerlandica on the islands. A Dutch report of 1879 mentioned that many decades after the official abolition of the slave trade in the Dutch possessions, captured mountain people were being sent from Kui and Kolana to Liquiçá on Timor as slaves (Schapper and Wellfelt 2018, 101). It seems that the Raja of Kui was acting as a slave merchant, acquiring slaves from villages in central Alor and then shipping them to Portuguese Timor. At around the same time the Raja of Kui sent tributes consisting of beeswax to Oecussi in Portuguese Timor in the hope of obtaining assistance to fight the mountain villagers.

Following a local war between the district of Molelang adjacent to Manatang on the south coast of Kui and Lalelang, the location of which we cannot identify, Raja Pasoma of Kui and the Raja of Alor were summoned in front of the Resident of Kupang in 1886 and forced to agree a settlement (Seran 2004, 44-45). They were each given a ceremonial walking cane or rottingknoppen embossed with the Dutch coat-of-arms and a Dutch flag.

Raja Pasoma died in 1890 or 1891 and was succeeded by his nephew’s eldest son, Taru Soma I (in some sources Tarsoma), who led until 1897 when his younger brother Gaw Amalei replaced him. Under Raja Taru Soma, the Kalong (Klon) region of Probur was officially incorporated into the landschap of Kui, having previously been contested by the Rajas of Alor (Van Galen 1946, 35). It became a new kapitanship of Kui.

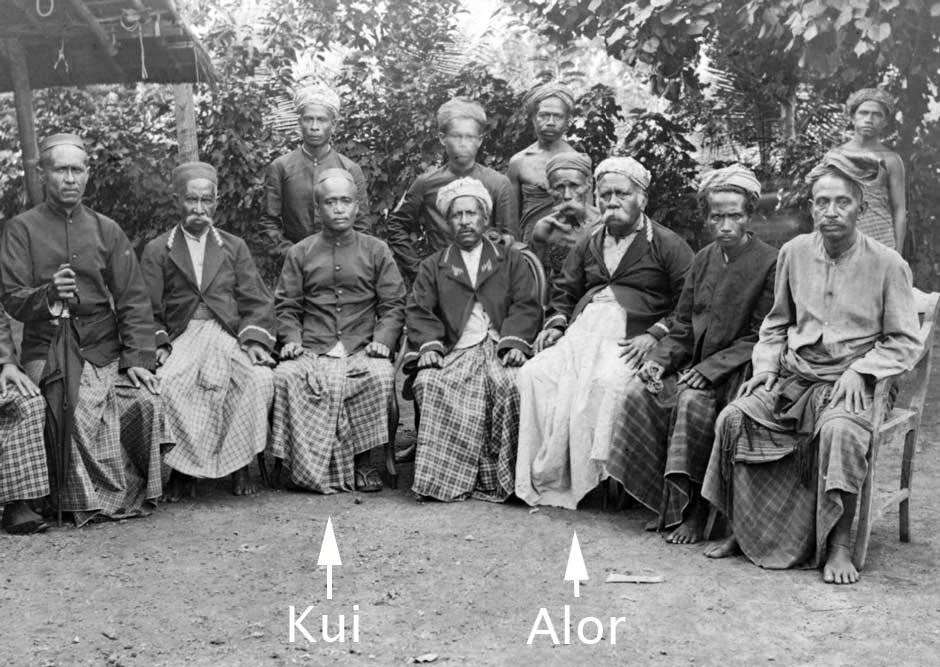

An 1898 group photo of some of the rajas, kapitans and fettors of Alor. We have highlighted Raja Gaw Amalei of Kui, left, and Kapitan Nampira Bukan of Dulolong, right

In 1898 Raja Gaw Amalei was pressurised into signing the so-called Timor Declaration, an acknowledgement of Dutch supremacy and obedience to Dutch commands and the more detailed Korte Verklaring (Short Declaration) in return for a measure of native self-government. Despite this Dutch interference remained minimal. Raja Gaw Amalei signed another agreement related to the imposition of taxes in 1901.

Three contrasting cultures in Kalabahi in 1898: the wife of the Dutch posthouder A. C. Meulemans with the wife of Fokko Fokkens, the acting Resident of Timor, local Abui tribesmen, and two Alorese officials flanking Kapitan Nampira Bukan of Dulolong, who became the temporary Raja of Alor from 1908 until 1915 (KITLV Creative Commons)

It seems that a dispute between the Rajas of Kui and Batulolong in the years before 1900 was resolved thanks to the intervention of Nampira Bukan of Dulolong (Van Galen 1946, 27). The Dutch rewarded the Raja with a golden kopiah kerajaan brimless cap. In order to improve relations between Kerajaan Kui and Kerajaan Alor, Raja Gaw Amelie took a wife from the family of Kapitan Nampira of Dulolong (Seran 2004, 45).

After half a century of Dutch rule the policy applied to the more isolated islands like Alor was about to change drastically. Having just successfully crushed a long-running insurgency in the Sultanate of Aceh, the military leader Joannes van Heutsz was appointed Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies in 1904. Faced with numerous ongoing local insurrections across the Outer Islands, van Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule. The following year he appointed J. F. A. de Rooy as the new Resident of Timor, with instructions to exert direct control over the native rulers in his residency.

In 1906 de Rooy promoted A. C. Meulemans to become the first Controleur of Alor at Alor Kecil and installed A. F. Morgenstern as the new posthouder (Regeeringsalmanak voor Nederlandsch-Indie 1907). It did not take the new incumbent long to realise that although the Dutch-appointed coastal Rajas took it upon themselves to exert their authority over their respective hinterlands, the animist mountain people did not accept them as their leaders (Morgenstern 1909 cited by van Galen 1946, 2). The Rajas spoke a different language, had a different religion, did not understand their adat and in some cases had not even visited the regions concerned.

The Dutch at Kupang did not focus their attention onto Alor Island until 1910. In July, Lieutenant Adelberg was sent from Kupang to Kalabahi with three detachments of marechaussee. It seems the mountain dwellers on Alor respected the well-armed troops and were generally cooperative (van Galen 2010, 22).

The map produced by Adelberg’s surveyor shows that there was only a limited military incursion into the western part of Kerajaan Kui.

Part of the survey of Alor Island included in Anonymous 1914

Lieutenant Adelberg’s campaign resulted in a report about the state of affairs on Alor Island at that time, although many of the comments within are in a generalised form (Anon 1914). Kui was still one of the same six rajadoms established in the 1850s. Kui and Mataru, but especially Kolana, still maintained a relationship with Portuguese Timor. Few chiefs exercised much authority over their subjects, but there were a few exceptions such as the Fettor (Lèr or Raja?) of Kui and Kapitan Nampira of Dulolong.

While the centre of the island appeared very fertile, Kui and Mataru seemed to be less so (1914,81). The landscape of Kui was ideal for breeding goats, although in practise this was almost impossible because of the frequent occurrence of pythons in that region! The coastal villages mainly engaged in fishing. Kui had 23 perahus, less than the 55 of Alor Kecil but more than Dulolong (22) and Alor Besar (20). Of the 23, two were large with a capacity of 50-60 people, one was of medium size capable of carrying around 25 people and the remaining 20 were small, carrying 3 to 6 people. Mataru had only 4 small perahu. There was little industry on the island, the main activity being the weaving of coarse sarongs by the coastal inhabitants.

Most settlements across the island were built on flat ground or on terraces and were surrounded by heavy bamboo fences, often reinforced with cactus. However Kui was unusual, being surrounded by a defensive stonewall (1914, 74). According to posthouder Meulemans, the population of Kui was divided between two tribes: the Barawahieng (a term applied to the Abui) and the Kelong (Klon). It is clear that he was only referring to the mountain villages of Kui. Meulemans thought that the mountain populations of Mataru and Batulolong probably also belonged to the Barawahieng or Abui tribe because they spoke roughly the same language. Generally the people of Alor were strong, well-built and tough but there were some ‘unhealthy centres’, presumably with sickly people, one being Sulamaka on the south coast of Kui. We cannot identify its location.

The coastal population of Kui was partly from Timor (Anonymous 1914, 77). From Kui the Timorese immigrants gradually spread eastward and settled successively in Pureman and Kolana. This might explain why the Masin language is similar to the Kiraman spoken in Batulolong and Sibera. By contrast the beach population of Mataru seems to have originated from mountain dwellers who had migrated southwards down to the coast. While coastal Kui was Islamic ‘at least in name’, the populations of Mataru, Batulolong, Pureman and Kolana were ‘animist heathens’.

The population of Alor Island was registered, their muskets and other weapons were destroyed and the Rajas were pressurised to sign the Korte Verklaring or ‘Short Declaration’ – a one-sided agreement designed by van Heutsz in which each Raja recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies. The census enabled the Dutch to levy taxes in the form of heerendiensten or unpaid labour (Dietrich 1985, 279). Men were brought in from the mountain villages to construct roads in and around the capital of Kalabahi and elsewhere. Inevitably, Dutch taxation and forced labour soon led to local hostilities.

The 1911 census covered five land- or radjaschappen: Alor, Kui, Batulolong, Pureman and Kolana. These were generically known as swaprajas, self-governing domains (swa meaning autonomous and praja meaning governing). The population of Radjaschaap Kui totalled 8,468, some 22.3% of the whole of Alor Island (van Dalen 1928a, 219). Apparently Lerabaing had the reputation of being a pirate’s nest. By 1914 the number of radjaschappen had risen to six, with the addition of Mataru, just to the east of Kui (Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap 1914, 70).

Under their new hands-on policy, the Dutch placed increased demands on the local Rajas – they needed to maintain the new system of registration, construct new roads and build schools. On Alor Island only two leaders – Raja Gaw Amalei of Kerajaan Kui and the newly installed Raja Nampira Bukang of Kerajaan Alor – were considered up to the job (du Croo 1964, 462). The first school was opened in Lerabaing in 1912, run by a teacher called Ngefak (van Dalen 1928a, 161). Two years later there was an uprising against the Dutch and their client Rajas in the districts of Probur, Alor Besar and Atimelang. The Dutch organised military patrols in the Kalong (Klon) region in the kapitanship of Probur (Van Galen 1946, 22).

In 1914 Raja Gaw Amalei was succeeded by Raja Taru Soma II. Under his rule another dispute took place between the Kerajaans of Kui and Alor, Raja Taru Soma II being concerned over the claims of Kerajaan Alor over the southwest part of the island (Seran 2004, 46). He gained support from the Dutch who arranged a meeting between the two Rajas at which it was agreed that Kerajaan Kui’s borders would be extended and that the border between the two domains would be the river running between the villages of Fanating and Moru (Haan 1995). In return for their support, the Raja of Kui committed to increase his loyalty towards the Dutch, and ensure the full payment of taxes and provide more corveé labout for road construction.

On the nights of 4 and 5 August 1915, Lerabaing was plundered and almost completely burnt down by 150 warlike mountain dwellers from the village of Kamelelang, rebelling against the Raja of Kui for the imposition of corvée labour and taxes. Nine villagers were killed and the Raja’s residence and a Chinese shop were incinerated. Reinforcements were sent from Kupang and the rebellion was finally supressed with military support from the Raja of Kui. Apparently dozens of rebels were killed (Doko 1981, 57). Subsequently some of the mountain dwellers were moved down from their villages to more accessible locations where they could be better controlled. Following the attack, some residents decided to move from Lerabaing to Moru and a representative of the Raja was located there (Seran 2004, 47).

In February 1916 the Dutch combined the adjacent landschappen of Kui and Mataru, Raja La Kussie, the last chief of Mataru, having died in 1913 (Stokhof 1984, 132). Mataru was added as a new kapitanship, overseen by a Kapitan from Lerabaing.

In 1917 Raja Taru Soma II was succeeded by Raja Dain Soma (or Daeng Taru Kinanggi according to Seran). That very same year the Dutch authorities placed Kerajaan Kui under the brief rule of the Kapitan of Limbur at Atimelang, one of the five kapitanships of landschap Alor (Gomang 1993, 4). This only lasted until the outbreak of hostilities later the following year – see below. Because Raja Dain Soma strictly enforced Dutch demands for taxes and labour he faced an uprising by angry villagers in Mataru (Seran 2004, 47).

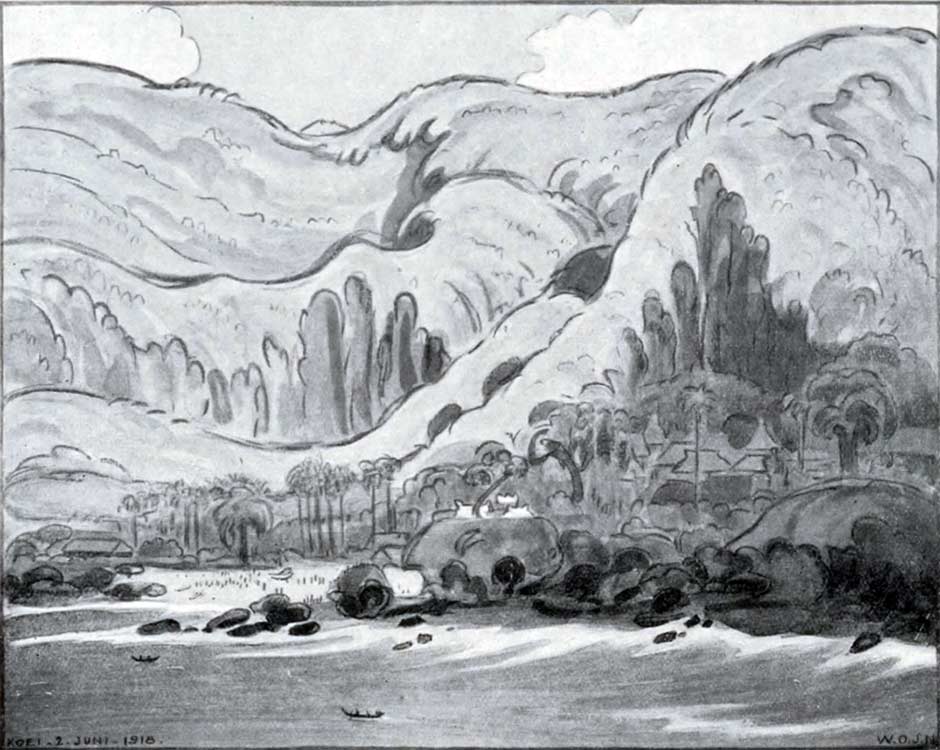

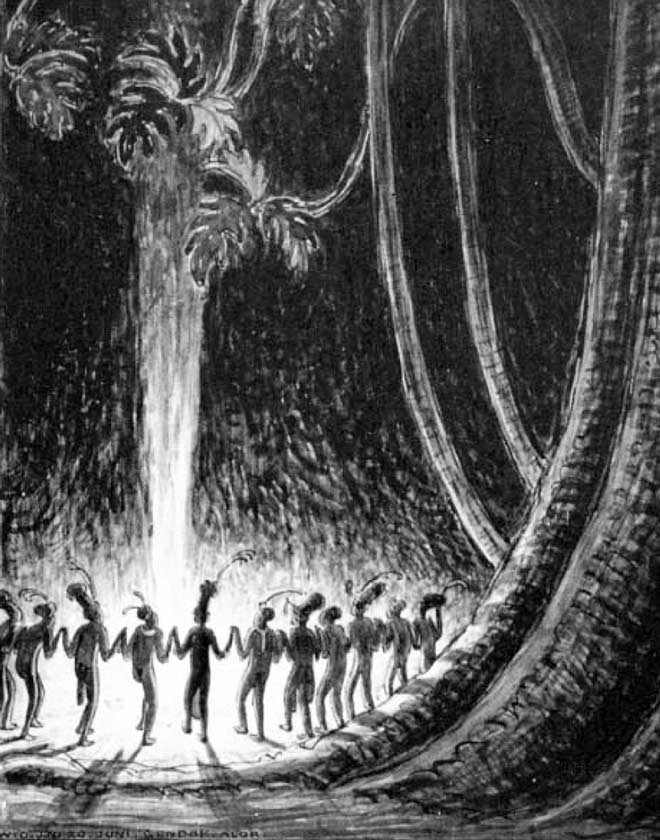

Thanks to the Dutch artist Otto Nieuwenkamp we have been left a good description of Lerabaing in 1918. On the afternoon of 2 June he was aboard the small government steamship Canopus on its way back from Kisar, Wetar and Liran to Kalabahi when it briefly moored in front of the village. He did not have time to go ashore at that time but was impressed by its picturesque location, the village perched on a rocky plateau set against ‘high, capricious mountains and deep, dark valleys’ (Nieuwenkamp 1922, 68-69). The inhabitants gathered on the beach and rocks as they were pounded by a huge surf. Fortunately the artist had time to make a good sketch of the view.

The front of Lerabaing village on 2 June 1918

Nieuwenkamp was so impressed that on the 16 June he set off from Kalabahi on a five-day round trip to Kui, travelling on horseback with First Lieutenant W. Muller, the gezaghebber of Alor. Once they reached Buraga two days later they were met by the Raja of Kui and two of his relatives. After crossing the shallow Buraga River they stopped at a few houses where a man had just lost half of his face after being attacked by a crocodile. He was the fourth local to have been attacked by a crocodile that year, the previous three having been eaten.

The last leg of the journey to Lerabaing was difficult, entailing crossing large boulders, banks of loose stones and a long dyke flanked by steep cliffs from which great lumps had collapsed on one side and the sea on the other. After galloping through a vast cotton plantation they finally reached the village. Nieuwenkamp first explored some impressive nearby caves to the east of the village that he had seen from the boat. The interior was like a cathedral with a huge round vault. There were three large openings facing the ferocious surf, one of which offered a view of the village, which Nieuwenkamp recorded in another sketch.

The huge coastal cave looking towards Lerabaing

While they camped overnight at Lerabaing the villagers, along with visitors from the surrounding hills, performed a lego-lego dance in the dance square on the other side of the village with singing and the beating of drums and gongs, lasting from the evening until the following morning. The circular dance began slowly and quietly but then became faster and louder.

Lerabaing was located in a well-protected position, surrounded by a wall of coral blocks and a small river on the eastern side. On the seaward side, the perpendicular rocky coast offered further security. The entrances on the west and east sides were protected by a wall and heavy wooden gates that were closed at night – probably installed after the devastating attack in 1915.

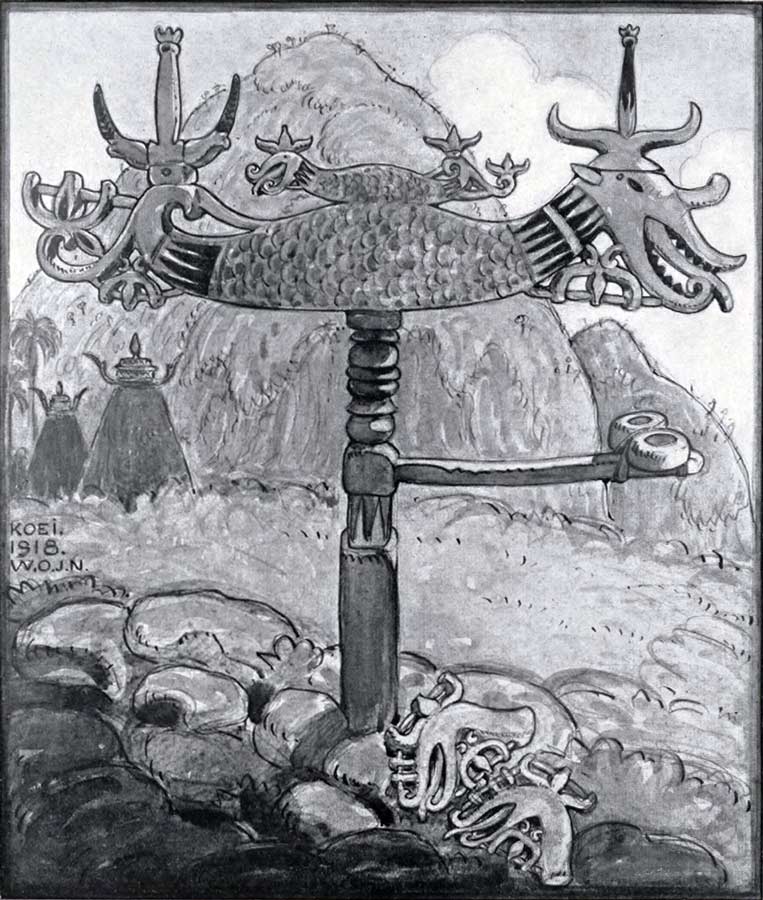

Nieuwenkamp described the simple mosque as not very beautiful, apart from its strange roof and ridge decorated with ‘pagan motifs, derived from nagas’. Close by were two bronze cannons half buried in the ground, one bearing a Portuguese inscription and the date of 1699, indicating past links with the Portuguese. On a rocky outcrop overlooking the sea stood three large, whitewashed stone tombs of former rajas, two built of brick masonry and decorated with ‘pagan motifs’. The other had two wooden posts, indicating it was the grave of a Muslim.

Next to one of the roads into the village there was a pile of stones and the remains of an old, large wooden idol, brightly painted with a big naga carrying a smaller naga on its back. The Raja explained that such gods were no longer worshipped in the village. Nieuwenkamp located the elderly owner who was unwilling to sell the parts and see them shipped back to Holland, especially as he made a sacrifice to the idol every year. They therefore reassembled the idol, tying the parts together with string. It had two wooden cups for making offerings. The old man was so delighted that he gifted Nieuwenkamp four other pieces of carved wood that were also laying on the stone cairn, the heads and tails of two further nagas. Back in Holland one head and tail was donated to the Colonial Institute in Amsterdam.

Drawing showing the reconstructed naga idol but without the string. Two other carved naga heads lay on the stones. Note the decorated roofs behind. Nieuwenkamp 1918.

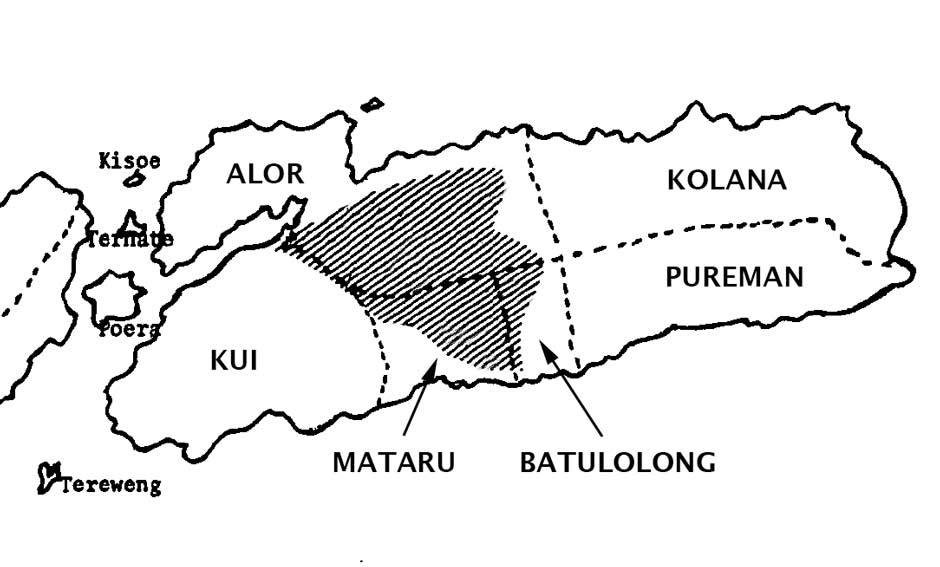

In the following September of 1918 there was a serious uprising of Berawahing clan members located in the mountain districts of Lembur-Welai in the north and Mataru in the south, the latter being under the authority of the Raja of Kui. The underlying cause was resentment against Dutch demands for corvée labour, the capture of unregistered villagers and the imposition of fines and taxes (Van Galen 1946, 24). In their opposition to the Dutch, one village had even appointed a spiritual leader, a woman called Maleili, giving her the title ‘Sultane’. The rebellion may have been sparked by the arrival of Raja Bala Nampira of Dulolong on a tax-collecting visit. While staying at a temporary bivouac he was murdered by local villagers, who incinerated his camp with flaming arrows.

The location of the 1918 uprisings (hatched) in the landschappen of Alor Island

(Based on Stokhof 1984)

The gezaghebber of Alor, First Lieutenant W. Muller, set out to punish the three villages responsible, with the assistance of Raja Dain Soma of Kui (Nieuwenkamp 1922, 78-79). It was a challenging task as the villages were fortified with stonewalls built with embrasures as well as bamboo stockades blocking the paths. After taking Fungwati and Afenbeka in the north and rounding up the rebels, Dutch forces moved south to Mataru where they were assisted by warriors from Kui. The ‘Sultane’ was found among the dead and wounded and was arrested, after which the Raja of Kui plundered the village, taking bronze moko drums, gongs and other goods. Later the people of Mataru repeatedly requested the return of these goods, but without success. As a punishment the rebels were forced to move down to lower locations (Anon 1930).

Raja Dain Soma committed suicide in 1920 or 1921 and was succeeded by Raja Katang Koli Kinanggi, the younger the brother of Taru Soma I and Gaw Amalei (Regeerings-Almanak voor Nederlandsch-Indie 1937, 443).

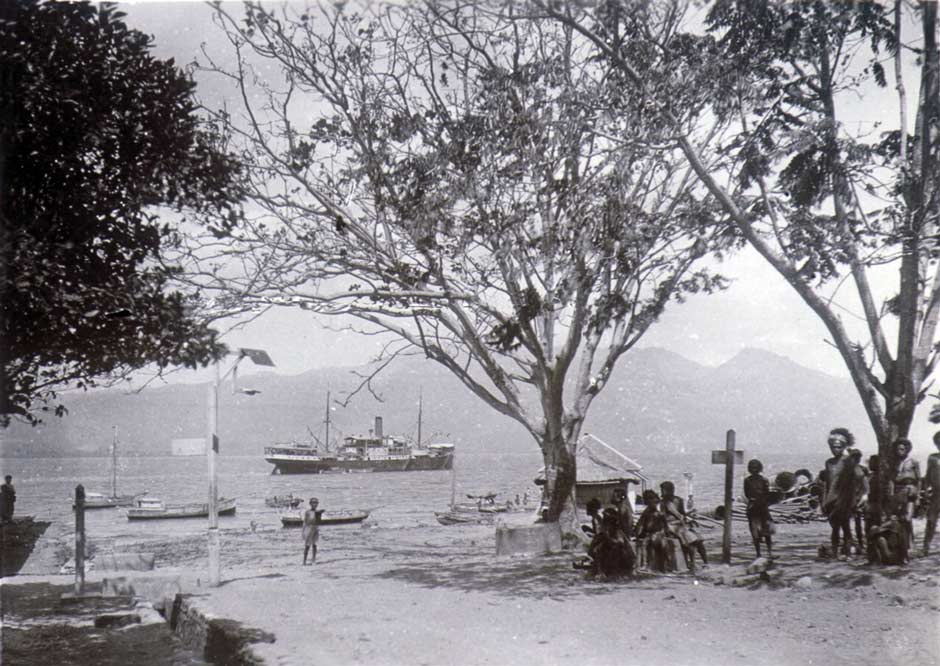

The wharf in Kalabahi in about 1925, photographed by Frits Ijspeert

The population of Kui-Klon in 1926

(Album given to C. Shultz, Resident of Timor, on his retirement, KITLV Creative Commons)

The territorial expansion of Kerajaan Kui continued during the reign of Raja Katang Koli Kinanggi, with the incorporation of the Hamap-speaking region (Seran 2004, 47). The Hamap resisted but were supressed by the Dutch, their leader, Teng Adang, being imprisoned in Kalabahi until 1928.

In 1930 local mountain tribes again attacked Lerabaing and destroyed some houses and the Raja’s residence. More residents relocated from Lerabaing to Moru, on the south coast of Kalabahi Bay (Katubi 2005, 66). Later that year the roof of the mosque was replaced with one made of tin.

The 1930 census identified the population of landschap Kui as 18,646, some 20.6% of the Alor Island total (Paulus 1935, 5). Although the number of residents (including children) recorded in the later taxation records of 1937 was 13,931, this clearly did not represent the total population.

Clearly the location of Lerabaing was unsuitable for farming or development, while Moru lay on an extensive plain that was close to the Dutch administration in Kalabahi. Consequently, in 1933, Raja Katang Koli decided to relocate his administration to Moru and encouraged some of his people to join him there (Katubi 2005, 64). However at that time there were not yet any Klon, Hamap or Abui in Moru. Two years later in 1935 a small Islamic school was opened in Moru along with a branch of the anti-Dutch Partai Syarikat Islam, thereby introducing a reformist version of Islam into the local culture (Gomang 1993, 117).

In 1939 there were just four rajaships on Alor: Alor, Kui, Batulolong and Kolana (Du Bois 1944, 16). Pureman had merged with Kolana in 1927.

In 1939 Raja Katang Koli Kinanggi abdicated and the Resident of Timor entrusted the Raja’s son, Banla Kinanggi, to take on a caretaker role as Regent. It seems that by now there was a telephone line from Kalabahi to Moru and to Lerabaing. In March 1942 there was an uprising of mountain villagers against taxation that spread from one kapitanship to another. Some rural villagers attempted to march on Kalabahi and burn the town.

In June 1942 the first Japanese warship arrived at Kalabahi and unloaded firearms and munitions. Facing no serious resistance, by July the Japanese had established their garrison in the town (Du Bois 1961, xiv). Their base immediately came under an attack from Allied long-range bombers stationed in Australia, which started fires (US Office of War Information, 18 July 1942). Later that year they attacked Japanese troops based in Lerabaing destroying the Raja’s residence and other buildings (Kinanggi 2018 and 2020). Another mission in late 1942 started fires among wharf installations at the Japanese Kalabahi naval base (A Week of the War 1942, 3). Further bombing raids took place in August and November 1944.

The arrival of the Japanese quickly reignited the earlier tribal rebellion, which had by then spread as far as Mataru, still incensed by their loss of mokos and gongs to the Raja of Kui in 1918 (Van Galen 1946, 83). Because of an untrue rumour that the Raja of Kui had killed the Kapitan of Mataru, the insurgents threatened to retaliate by killing the Kapitan of Lerabaing. The Raja sent them a message that their Kapitan was fine but the insurgents murdered the hapless young courier and incinerated several Mataru villages. To quell the uprising the Raja of Kui sent the Kapitan of Mataru to plead with them but he was then threatened and chased away.

As the rebels approached Lerabaing, a perahu arrived with eight Japanese who delivered just three rifles and ammunition, which proved sufficient to disburse the insurgents.

The Japanese in Kalabahi moved decisively against the rebellious kampongs, sending out missives demanding that the rebel leaders appear before them in Kalabahi. The Mataru rebels said they would only obey if their mokos and gongs were returned. In response a troop of 60 marines led by an officer called Nakamura violently attacked some of the kampongs. Some village leaders were shot or bayoneted, others were decapitated and some imprisoned (Weaver 1973, 32). Several kampongs were incinerated. Fearing for their lives, the Mataru rebels reported to Kalabahi and begged forgiveness. Two of their chiefs were jailed. Although van Galen estimated the total number of dead would not have exceeded fifty, one administrator suggested some 150 to 200 had been killed in Mataru alone. Only one Japanese soldier died.

On 20 February 1943 the Raja of Kui went from Moru to Lerabaing in order to hand out tax notifications, but only a few local chiefs appeared. He was informed by the Kapitan that the insurgents in Mataru would not pay any taxes. To resolve the dispute, the Japanese ordered the Raja of Kui to send 30 moko to Mataru. The Raja acquired 31 small moko and gongs and summoned the chiefs of Mataru to meet him in Moru. However the offer was rejected because the chiefs wanted their original property to be restored. The impatient Japanese dispatched soldiers and forced the rebels to report to Kalabahi where they were warned that if they rebelled again they would be shot. Order was only finally restored in October 1943. During these troubles, Banla Kinanggi persuaded yet more people to move from Lerabaing to Moru (Nasarudin Kinanggi 2017).

Under the Japanese infamous system of conscript romushas or labourers, many people from Alor were forced to toil on roads and military installations, both locally and on Timor, working under harsh conditions. Many died from disease and exhaustion. A comparison of the Dutch tax records for 1937 and 1946 showed a decline of 15% in adult males in landschap Kui despite a 26% increase in the rest of the population, which van Galen attributes to labourers having been forcibly shipped to Timor by the heartless Japanese (1946, 39). Marion Klamer found that most elderly people tell stories about the cruel and barbarous treatment of local people by members of the Japanese army, as well as a lack of food and clothes during their occupation (Klamer 2010, 14). To maintain local order and prevent further uprisings, small detachments of Japanese troops were sent out at irregular intervals to crisscross the island.

After the Japanese Emperor capitulated to the Allies on 15 August 1945, Japanese forces departed from Alor in late September. On 3 November an Australian corvette arrived at Kalabahi carrying the former Dutch controleur G. A. M. van Galen and a detachment of Netherlands East Indies troops. Onderafdeeling Alor was back under Dutch East Indies rule. On 9 November the rulers and senior chiefs of the four landschappen – Alor, Kui, Batulolong and Kolana – were summoned to Kalabahi to witness the raising of the Dutch flag. The Dutch appointed Banla Kinanggi as the official Raja of Kui.

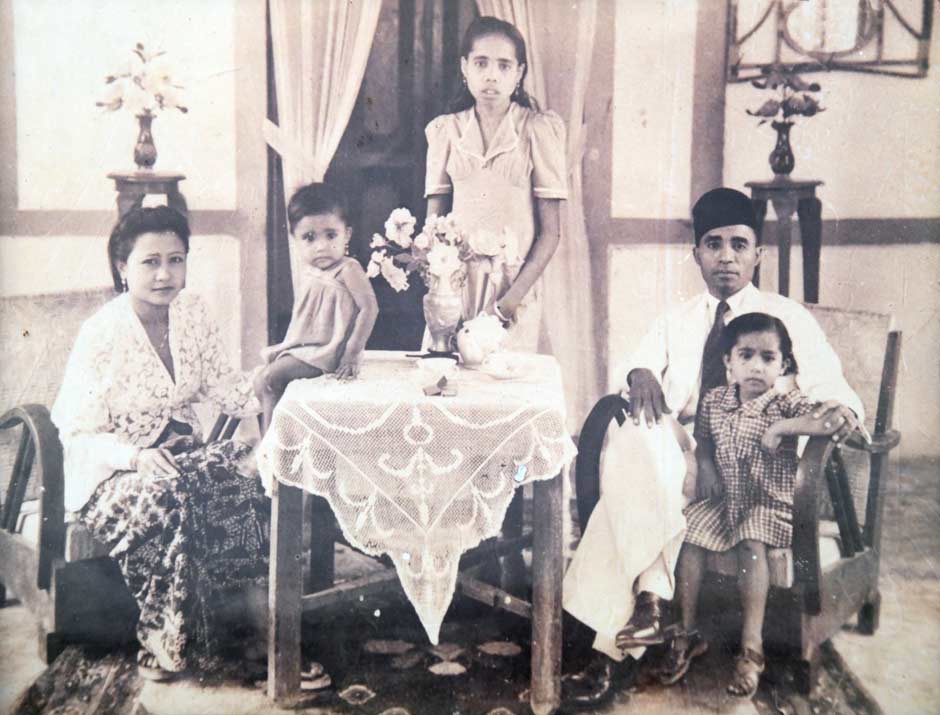

The young Raja Banla Kinanggi with his family at Moru

In landschap Kui the villagers had been forced to collect a significant portion of their harvest for the Japanese and that year’s crop was still present in their local storehouses. As they had not received any payment for this produce the Dutch decided that it should be returned to the respective farmers. Raja Kinanggi was instructed to supervise its redistribution (Van Galen 1946, 88).

The number of Kui residents (including children) recorded in the taxation records for 1946 was 15,304, probably well below the total population at that time (Van Galen 1946, 39). Van Galen reported that the conversion of many mountain villagers to Christianity had heightened longstanding tensions with the coastal Islamic populations such as Lerabaing, which was completely Islamic. The outbreak of revolts after the war had been prevented by the religious neutrality of the Dutch, and in the case of Kui due to the ‘very moderate’ position of its Raja (Van Galen 1946, 43).

In van Galen’s opinion, the populations in much of Alor, especially in the landschap of Kui as well as the communities of Welai on the neck of the Kabola Peninsula and Limbur to its east, were still ‘utterly primitive’. At that time the roads on Alor were just horse tracks, although there was a wider track from Alor Kecil to Kalabahi and on to Moru, although the bridges of this track were unsuitable for cars (Van Galen 1946, 75). In 1947 some more of the Hamap community relocated from Foang to Moru (Katabi 2005, 66).

The Dutch had created the United States of Indonesia (Republic Indonesia Serikat, RIS) on Christmas Eve 1946, transforming the former Timor Residency (Residentie Timor en Onderhoorigheden) into the State of East Indonesia (Negara Indonesia Timur or NIT). Indonesia finally gained independence on 17 August 1949 and on 15 August 1950 the RIS was transformed into the Republic of Indonesia and NIT was dissolved. However its leadership had no choice other than to maintain the previous Dutch system of regional governance. The Regional Government Envoy (Utusan Pemerintah Daerah) Ludgerus Poluan was put in charge of Onderafdeeling Alor, which remained part of Nusa Tenggara Timur within the Lesser Sunda Province (Provinsi Sunda Kecil) composed of Bali, NTB and NTT. Kui remained as one of eight landschappen or swaprajas within Onderafdeeling Alor, headed by Raja Banla Kinanggi.

Amongst the Republic’s many problems, one was to replace the authority of the many traditional, and sometimes powerful, local ruling aristocracies with a modern system of regional and local government.

In 1958 the Indonesian government approved Law No. 69 (Statute Book of 1958 No.122) creating two tiers of autonomous regions. The Lesser Sunda Province was dissolved into three Autonomous Level I Regions – Daerah Swatantra Tingkat I: Bali, West Nusa Tenggara (NTB) and East Nusa Tenggara (NTT). These were then divided into 12 Autonomous Level II Regions – Daerah Swatantra Tingkat II. One of these was Alor Autonomous Level II Region, which came into existence on 20 December 1958. The Governor of NTT appointed Syarif Abdullah, the older brother of Sarinah Abdullah (the wife of King Banla Kinanggi), as its first Acting Head or Bupati. He also appointed Bapak Pelupesi as acting Camat of Kecamatan Alor Barat, based in its administrative centre of Moru (Nasarudin Kinanggi 2020).

This law transferred political power from the traditional regional Rajas of Alor to a centralised government administration in Kalabahi. Henceforth the responsibilities of the Rajas of Kui, Alor Batulolong and Kolana would be restricted to matters of customary law (adat).

Raja Banla Kinanggi, the last traditional leader of Kui, and his wife Sarinah Abdullah

Raja Banla Kinanggi experienced these changes for only a short time – he died 20 December 1959, becoming the last official ruling Raja of Kui. He was poisoned at the young age of just 43 for reasons that still remain a mystery. It is rumoured that the motive for his murder was a matter of competition, possibly rivalry. Remarkably his apparent murder was not reported to the police authorities.

Banla Kinanggi had nine children, five sons and four daughters, born as follows:

Rosinah Kinanggi

Maryam Kinanggi

Muhammad Kinanggi

Nasrudin Kinanggi

Mochtar Kinanggi

Ramlan Kinanggi

Syamsudin Kinanggi

Annisa Kinanggi

Rahmi Kinanggi

The eldest son, Muhammad Kinanggi, had been born in Moru on 2 February 1949, so at the time of his father’s death was only 10-years-old. However according to adat he automatically became the Eighth Raja of Kui (Banla Kinanggi 2020). As in most other Kingdoms, in Kerajaan Kui the eldest son became Raja on the death of his father. As was the tradition in Kui, no official ceremony of appointment was involved. Apparently some considered him too young to be appointed Raja (Nasruddin Kinanggi 2020). Obviously clan elders must have been involved in important decision-making. It has also been suggested that the Bupati of Alor, Syarif Abdullah, had some influence on the activities in Kui.

However Syarif Abdullah's sojourn as Bupati of Alor Daerah Swatantra Tingkat was short-lived. In 1960 he was replaced by Bupati Jhon Bastian Denu.

Meanwhile further changes were made to the system of local government. On 1 July 1962 the government of NTT abolished the system of swaprajas. Then on 1 September 1965, Law No. 18 resulted in the former Autonomous Level I Regions being transformed into Provinsi or Provinces and the Autonomous Level II Regions being transformed into Kabupaten or Regencies.

Sometime later, while Muhammad Kinanggi was still at high school in Kalabahi he decided to change his first name to Mochammad, which he maintained for the rest of his life.

Raja Mochammad Kinanggi eventually married Saida Sutio in 1977 when he was 28-years-old. Ibu Sutio was not from one of the traditional noble families of Kui or Alor. Her grandfather had been born on Java and later moved to settle on Alor.

Raja Mochammad Kinanggi and his wife Saida Sutio. Photograph kindly supplied by their eldest son, Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi, and reproduced with his permission

Raja Mochammad and his wife had five children, three daughters followed by two sons:

Sandra Meilita Kinanggi, born in 1978

Dessy Prihatini Kinanggi, born in 1979

Ratnasari Kinanggi, born in 1981

Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi, born in 1985

Arif Rahman Kinanggi, born in 1993

Raja Mochammad took up a career in politics and in 1992, when he was 43-years-old, was elected Chairman of Alor Regency DPRD (Regional People's Representative Assembly), a position he held until 1997.

In 1999 he moved to Kupang where he was elected as Secretary of the DPRD for the Province of Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT). However he still took an active part in Kui affairs and in 2005 he sent out an appeal to the Hamap community to move to Moru (Katabi 2005, 66).

As already mentioned, Raja Mochammad Kinanggi had four younger brothers of which Nasarudin Kinanggi was the eldest. Because of his relocation from Moru to Kupang, Raja Mochammad threfore asked his eldest brother to assist him with customary matters relating to Kui. Nasarudin Kinanggi adopted the title Raja Muda, essentially becoming a local viceroy acting on behalf of the Raja.

The authors with Raja Muda Nasarudin Kinanggi at the Kompleks Istana II of Kui at Moru in 2018

Sadly Raja Mochammad Kinanggi had a devastating stroke in 2006 that left him incapacitated and he was forced to retire from government. Despite continuing to live in Kupang he remained Raja of Kui, retaining his responsibilities for adat affairs.

In 2012 the Al-Taqwa mosque at Lerabaing was renovated and re-roofed. The opening ceremony was attended by communities of Abui, Harap and Klon, some of whom had helped in its reconstruction (Katubi 2020). Also in 2012, work began on the construction of a container dock at Moru. However the construction project has not been completed and the dock remains non-operational. Accusations of corruption have been made.

In 2017 Nasarudin Kinanggi submitted proposals for the expansion and development of Alor Barat Daya to the Secretary of Alor, Hopni Bukang.

Sadly Mochammad Kinanggi died in Kupang in May 2018. His eldest son, Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi, then aged 33, automatically became the Ninth Raja of Kui. As he was also based in Kupang, his uncle Nasaridin Kinanggi continued to assist with adat affairs in Moru.

Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi, the ninth and current Raja of Kui. Image kindly supplied by Banla Kinanggi and reproduced with his permission

Raja Banla Kinanggi had also been involved in the government of NTT and is currently a civil servant working in the general election commission. He is married and has three children. He takes an active role in the affairs of Kerajaan Kui and in November 2019 headed a meeting of all the clan elders in Moru.

On 31 July 2020, Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat, the Governor of the Province of Nusa Tenggara Timur, visited the Kompleks Istana II (Royal Palace II) of Kerajaan Kui in Moru to sign the plaque commemorating its inauguration. During the signing ceremony Governor Viktor was bestowed with the title of honorary citizen of the Kingdom of Kui.

Governor Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat signing the inaugeration plaque at the Kompleks Istana II in Moru. Image kindly supplied by Banla Kinanggi and reproduced with his permission

Governor Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat dressed in Kui ceremonial costume flanked by Raja Muda Nasruddin Kinanggi and his wife Asih Prastiwi

The Ruling Dynasty of Kerajaan Kui

According to van Galen, the ruling dynasty of Kui stretched back for 37 generations from the last official Raja, Banla Kinanggi, who died in 1959:

| # | Name | Notes |

| 1 | Maleikili or Malikili | The founder of the ruling dynasty of Kui who is thought to have sailed from Ende to Lerabaing |

| 2 | Maleilok | |

| 3 | Gaw Amalei | Possibly aka Tar Soma? |

| 4 | Atamalei | Converted to Islam by Kimales Gogo in the late 1500s or early 1600s. One oral narrative claims that he ruled from 1619 to 1638 and founded the Al-Taqwa mosque in 1633. There is no evidence for these dates. |

| 5 | Maleilok | |

| 6 | Banla | |

| 7 | Pa Soma | |

| 8 | Maleikili | |

| 9 | Kinanggi | |

| 10 | Maleilok | |

| 11 | Pa Soma | |

| 12 | Gaw Amale | |

| 13 | Banla | |

| 14 | Atamalei | |

| 15 | Gaw Amalei | |

| 16 | Maleilok | |

| 17 | Banla | |

| 18 | Kinanggi | |

| 19 | Banla | |

| 20 | Pasoma | |

| 21 | Atamalei | |

| 22 | Maleikili | |

| 23 | Atamalei | |

| 24 | Pasoma | |

| 25 | Kinanggi | |

| 26 | Atsom | |

| 27 | Pasoma | |

| 28 | Kinanggi | |

| 29 | Banla | |

| 30 | Gaw Amalei | |

| 31 | Banla | Ruled from 1851 to 1855. Also known as Raja Gesi or Gessie, he opposed the transfer of Alor from Portuguese to Dutch control and was deposed in 1855 |

| 32 | Pui Soma or Pasoma | The first Raja of Kui. The son of Banla who ruled from 1855 to 1891. His elder brother was Atamalei, whose son Kinanggi was the father of three subsequent Rajas: Taru Soma I, Go Amalei and Katang Koli. Referred to as Pui Soma Ata Meley of Kui by Gomang (1993, 78) |

| 33 | Taru Soma I | The second Raja of Kui who ruled from 1892 to 1897. The grandson of Atamalei, Pasoma’s elder brother. Sometimes written Tara Soma |

| 34 | Gaw Amalei | The third Raja of Kui who ruled from 1897 to 1914. He was one of the younger brothers of Taru Soma I |

| 35 | Taru Soma II | The fourth Raja of Kui who ruled from 1914 to 1917. He was the second son of Taru Soma I |

| 36 | Daeng or Dain Soma | The fifth Raja of Kui. The third son of Taru Soma I who ruled from 1917 until he committed suicide in 1920. Stokhof (1984) refers to him as TaEng Soma and states his term of reign as from 1918 to 1922. |

| 37 | Katang Koli | The sixth Raja of Kui. The youngest brother of Taru Soma I and Go Amalei. Ruled from 1921 to 1939, when he was removed. He was too young to be Raja during the reign of Taru Soma II. He died in 1942 |

| Banla Kinanggi | Appointed caretaker Raja Muda from 1939 to 1946, serving under the Japanese from 19442 to 1945 | |

| 38 | Banla Kinanggi | Appointed the seventh Raja of Kui from 1946 until his death on 20 December 1959. He was poisoned because he was too closely linked to the Dutch. He was the last official Raja of Kui |

| 39 | Mochammad Kinanggi | The eighth Raja of Kui who ruled from 1959 to 2018. The first son of Banla Kinanngi, he was only 10-years-old when his father died. He was already the head of parliament for the Province of NTT in Kupang in 2003. He died in Kupang in 2018 |

| 40 | Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi | The ninth Raja of Kui and the eldest son of Mochammad Kinanggi, born in 1985. He became the Raja of Kui in 2018 following the death of Raja Mochammad |

(Sources: De Indische Gids 1925, vol. 47, 534; van Galen 1946; Donald Tick 2020; Banla Yuan Permata Kinanggi 2020)

The Kui Language

The Kui language, strictly known as Masin Lak, is primarily Papuan in origin like most other Alor languages - with the sole exception of Alorese, which is Austronesian and linked to Lamaholot (Anceaux 1973). It is today spoken in Lerabaing and neighbouring Buraga, and also in Moru. In Buraga, Kui speakers are interspersed with Klon speakers, while in Moru, Kui speakers are mixed with Klon, Hamap and Abui (Windschuttel and Shiohara 2017, 111).

Those interested in what Masin Lak sounds like can listen to a Moru resident talking about the history of Kui here.

Kiraman is spoken further east and many Kui speakers see it as a distinct yet similar language. A recent Bayesian analysis of the Timor-Alor-Pantar languages shows that Masin and Kiraman are closely related (Kaiping and Klamer 2019).

Both Masin and Kiraman are south coastal languages classified among the Central Alor Group of Alor-Pantar languages and are weakly related to the neighbouring Abui and Kafoa inland mountain languages (Schapper and Wellfelt 2018, 99). Masin appears to be indigenous to Alor.

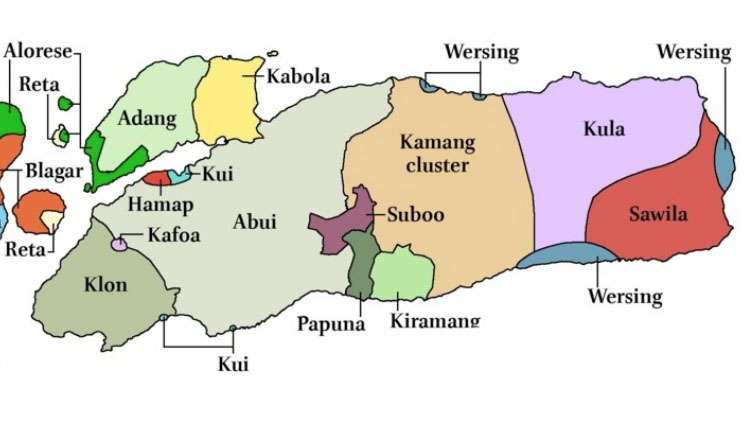

Language map of Alor Island. Klon is not as widespread as it appears, being confined to a limited number of villages. (Map courtesy of Owen Edwards, Leiden University, 2017)