Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Dutch Wax

The History of the Dutch Wax Industry and Vlisco

The Manufacturing Process

Some Examples of Vlisco Patterns

Bibliography

Dutch Wax

This is the story of how a classical Indonesian group of textiles was transformed into a range of designer fabrics targeted at middle-class women across West Africa. Initially copied in the mid-nineteenth century by the European textile industry, and eventually spurned by women on Java, they were forced to evolve into a completely different style of clothing fabric that became adopted as an important icon of African culture.

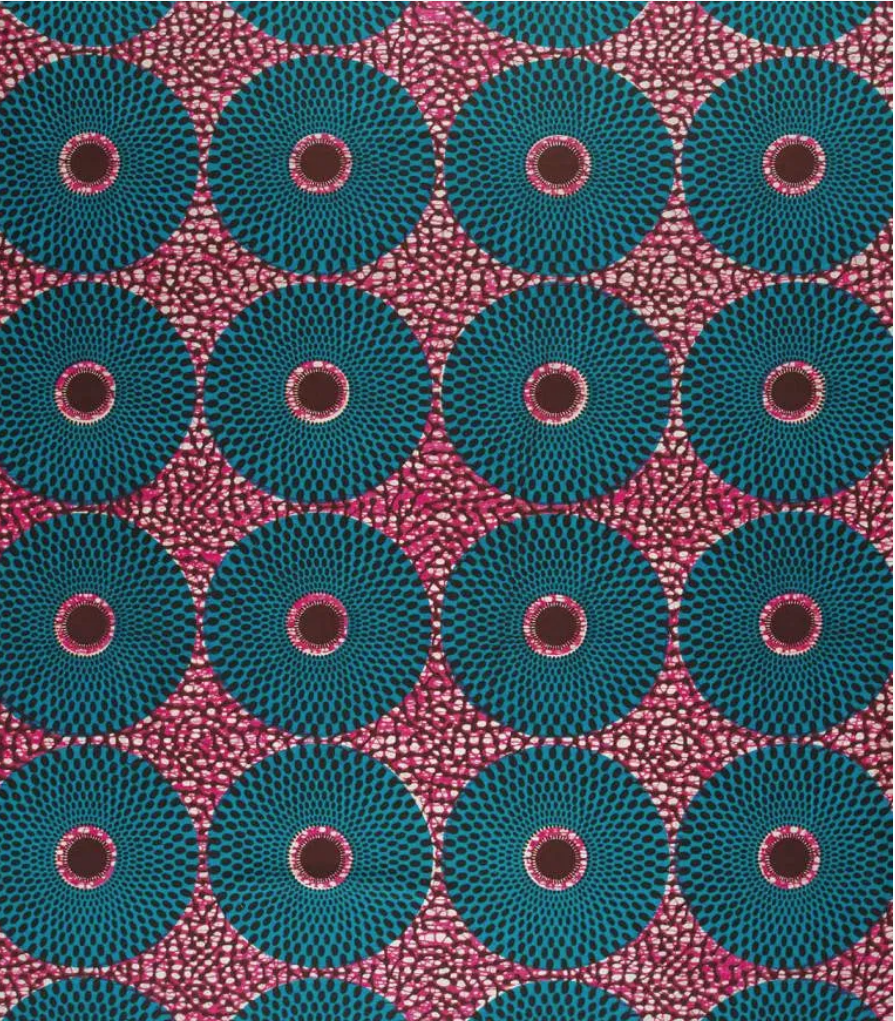

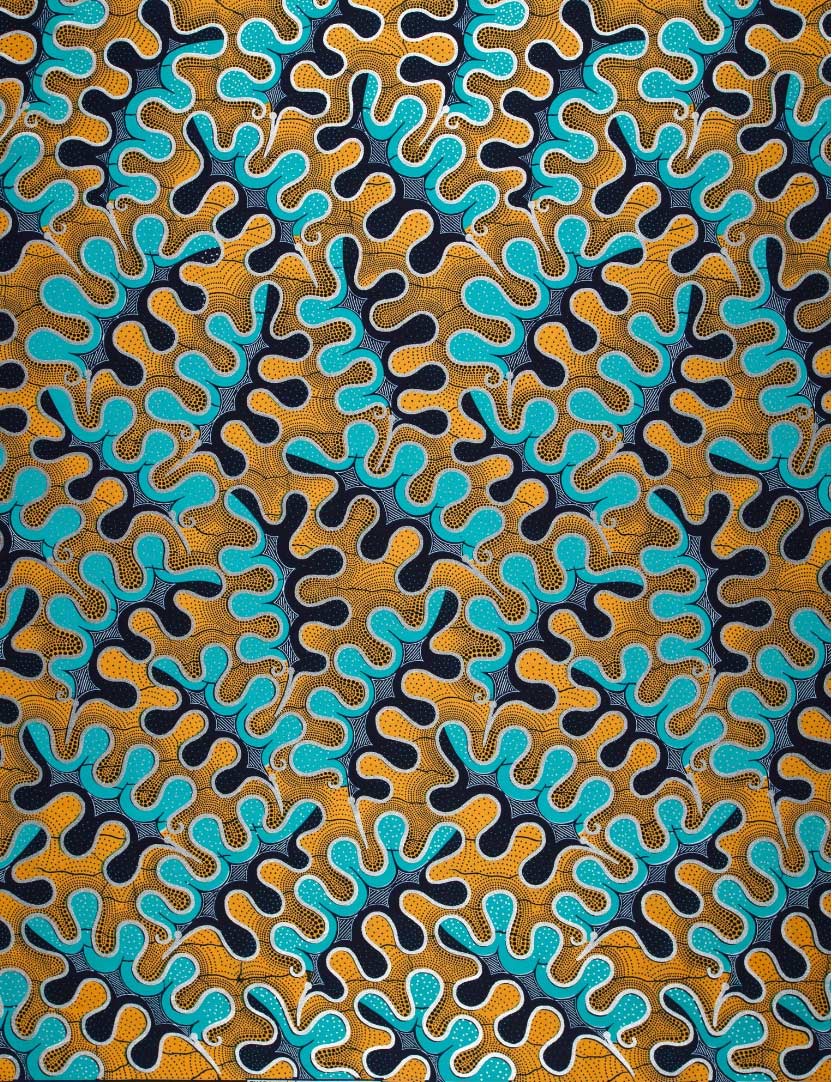

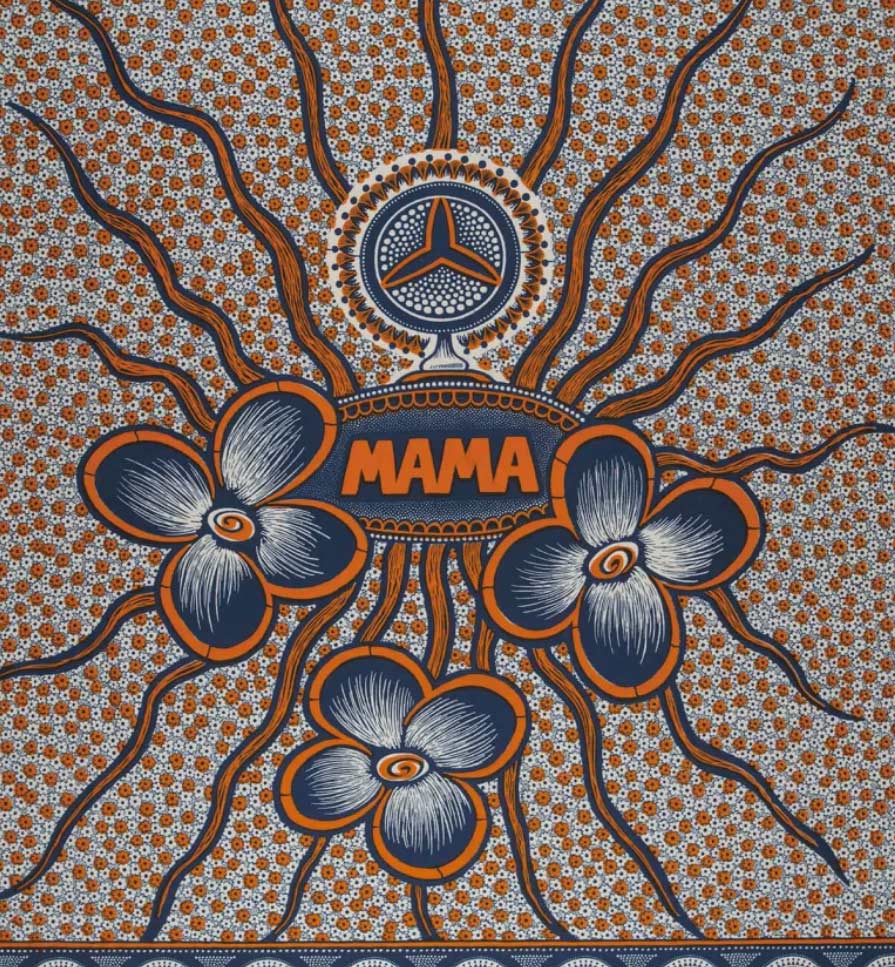

A Dutch wax pattern created by the designer Piet Snel for Vlisco in 1936, variously named Plaque-Plaque, Target or Nsu Bura (Ghanaian for water well). In Nigeria, the design is known as Record. (Wax Hollandais VL00633.213).

Dutch Wax, also called Wax Hollandais, is a mechanically printed wax-resist cotton textile, developed commercially in Holland primarily for the African market. In West Africa they are commonly called ankara prints, in Francophone Africa pagne or tissu wax and in East Africa kitenge, terms that are sometimes extended beyond true wax-resist printed cottons to encompass basic printed cottons, some of which imitate wax-resist cloth.

Inspired by Javanese batik, it was first produced in the nineteenth century. Since then it has evolved into a fashion brand with a huge range of patterns, mostly designed to appeal to its female West African customers. It is normally sold by the yard, the typical African consumer normally purchasing 6 yards, which is enough to make one complete costume: 3 yards for the lower body; 2 yards for the upper body; and 1 yard for the headdress.

The leading producer today is Vlisco Group (Vlisco Netherlands BV), a private company based in Helmond in North Brabant in The Netherlands. It is today the only manufacturer of wax prints in the EU.

Promotional campaign fashion shot for Vlisco’s 2018 Unique Naturals Collection

(Photographed by Tim Verhallen for Vlisco)

Vlisco textiles are often termed ‘Real Dutch Wax’. To qualify for this appellation they must be printed on cotton with bold and vivid colours, have a soft appearance with a blurred edge design that includes a crackle-effect to mimic batik.

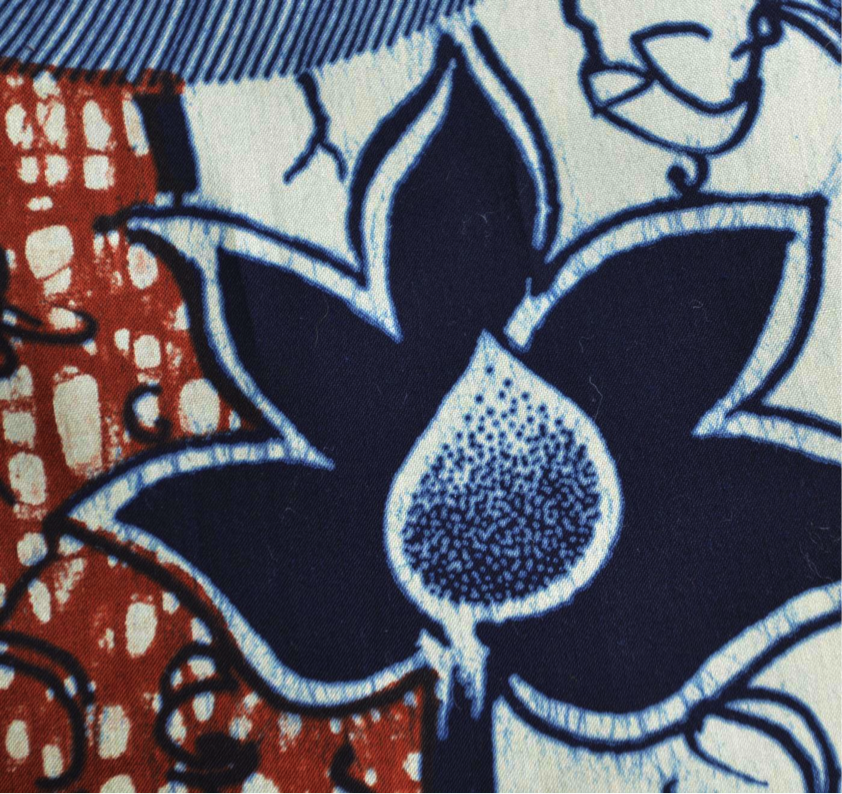

Detail from a Wax Hollandais design

Richardson Collection

There were several other important producers of wax-resist prints.

In Switzerland, the cotton printing company P. Blumer & Jenny, based at Schwanden near the canton of Glarus, began producing immitation batiks in 1841, thanks to the young Conrad Blumer who had just returned from an adventure through India and Indonesia (Nabholz-Kartaschoff 2019). Other manufacturers began producing in Thurgau and Zurich in the 1850s. They specialised in making resin-printed Indonesian style batiks specifically aimed at markets in British India and the Dutch East Indies. Apparently the Swiss batiks had less crackle than those made in Holland or England.

In England, A. Brunschweiler & Company, known as ABC Wax, was based in Hyde, Manchester. They began making wax prints at their long-established calico textile works in 1908. In 1992 ABC was acquired by the Hong Kong-based Cha Textile Group, and in 2005 it moved its production of wax prints to a new factory in Ghana owned by Akosombo Textiles, another Cha Group subsidiary. It closed the old Manchester plant two years later although it still maintains a small design studio in Hyde. Today Akosombo Textiles employs around 20,000 people, the vast majority in Africa, mostly managed by Chinese managers.

The main Chinese producer is Qingdao Phoenix Hitarget Printing & Dyeing Co based in Qingdao in eastern Shandong Province, who sell the Phoenix Hitarget brand of cloth, commonly called Hitarget. Their patterns tend to be illegally copied from Dutch designs. In Africa, DaViva based in Accra, Nigeria, is also part of the Hong Kong-owned Cha Textile Group. Sotiba Simpafric based in Dakar, Senegal, was liquidated several years ago, unable to compete with cheap Chinese and Indian imports.

Return to Top

The History of the Dutch Wax Industry and Vlisco

In 1844 the young Amsterdam entrepreneur Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen acquired his father’s small cotton printing company in the textile town of Helmond, just east of Eindhoven. It handprinted bleached cotton to produce chintz, upholstery and handkerchiefs.

The textile industry was going through a period of rapid change with increasing technical innovation and Manchester had already emerged as the dominant producer of printed cotton textiles. The 20-year old van Vlissingen found himself in charge of 50 employees and a factory with a brand new perrotine blockprinting machine, only recently invented by the French engineer Louis-Jérôme Perrot. Young and ambitious, he wanted to compete with the major international manufacturers.

It so happened that van Vlissingen’s uncle, Frederik (Frits) Hendrik Fentener van Vlissingen, owned a sugar plantation on Java in the Dutch East Indies. After visiting a small batik factory in the southern part of Java, Frits sent samples of the fabrics to Helmond. The Dutch company began making imitation factory-made batik and exporting it to the Dutch East Indies.

In Europe, the Dutch East Indies was perceived as an important export market and several other producers in Holland, the UK and Switzerland set out to automate the manual labour-intensive batik process and to ship their printed cotton back to the East Indies, undercutting local producers.

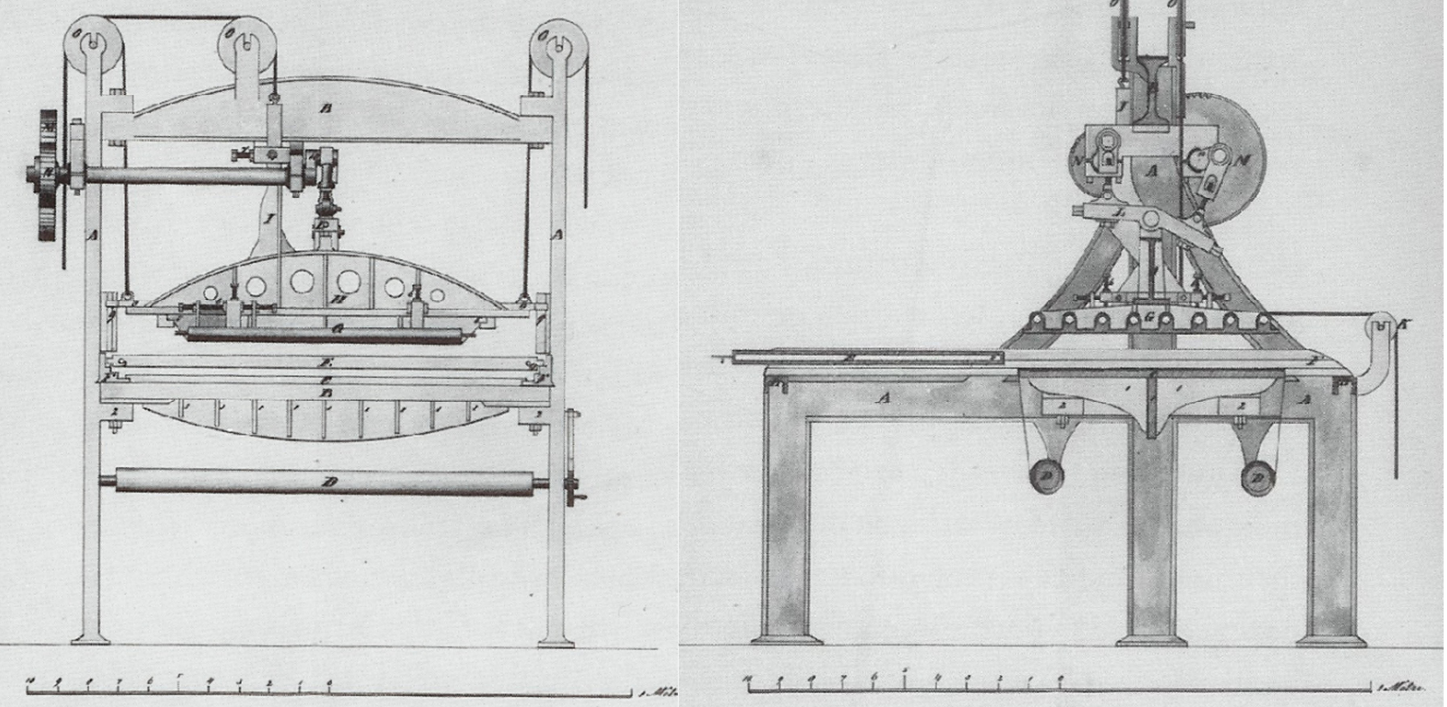

One of the more successful was another entrepreneur, Jean Baptiste Theodore Prévinaire, who in 1835 relocated his cotton company from Belgium to Haarlem in Holland. Belgium had just separated from Holland, so he had lost access to the large Dutch East Indies market. Prévinaire not only recruited experienced Belgian workers and British experts in cotton processing, but also conducted research into dyes and printing. In time he developed a special printing machine, named La Javanaise, that his successor trademarked in 1854. This applied a thin layer of resin to bleached cotton cloth, thereby mimicking the original batik process. As the resin dried it cracked, leaving thin veins and bubbles on the cloth. After dyeing, washing and drying, additional colours could be added using felt-padded wood blocks, creating slight overlapping and a hand-made appearance. The technique remained secret until 1910 and HKM emerged as the largest textile manufacturer in the Netherlands, producing the best imitation wax-batiks.

Drawing of La Javanaise

(from G. P. J. Verbong, Katoendrukken in Nederald vanaf 1800)

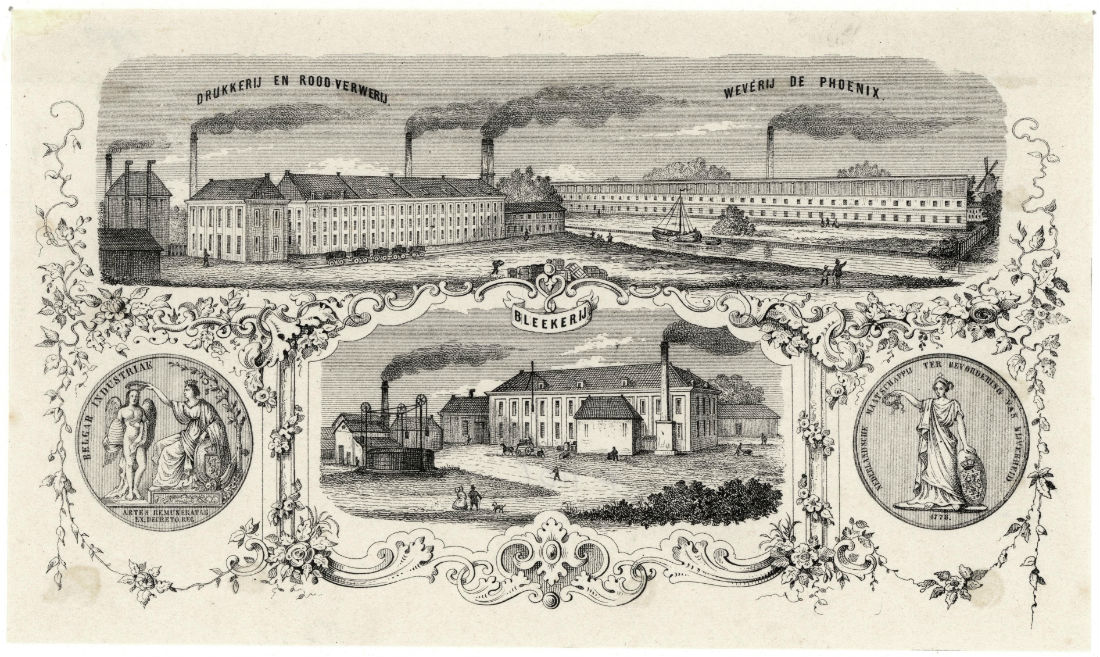

The factories of Prévinaire (North Holland Archive)

Likewise the textiles from Helmond were gaining a good reputation and P. F. van Vlissingen & Co. soon became the most important competitor to HKM. However both companies increasingly suffered from cheap wax-batik forgeries during the 1860s. Vlissingen responded by extending the factory and investing in a Manchester-made Mather & Platt roller printing machine. By 1864 more than 250 people were working in the factory.

Lithograph of the P. F. van Vlissingen and Co. factory on Binnen Parallelweg in the nineteenth century, with the castle and St. Lambertus church in the background.

When Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen died in 1868 his son and the son of his partner were both studying chemistry in Zurich and were too young to take over its management. The company was therefore temporarily run by the Technical Director, the Swiss dye specialist Conrad Hermann Deutsch.

The company suffered a severe downturn in the Dutch East Indies market in the 1870s, the differential tariff system in which Dutch products were exempted from import duties was abolished in 1872 and the Great Depression began the following year. It is also possible that Javanese batik makers became more productive and competitive by waxing with the tjap copper stamp rather that the labour intensive tjanting pen. It was at this difficult time in 1873 that Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen II and his nephew Jan Matthijsen took charge of the factory. Young and ambitious, they responded to the downturn by investing in new factory premises to double capacity in a bid to lower their costs of production. Business recovered, but another setback occurred in 1883 when a huge fire destroyed the complete factory. They responded by investing in an even bigger and more modern factory.

However the high dependence on the Dutch East Indies market was causing problems. Import tariffs were high and many Indonesians considered the Dutch-produced cloth inferior to domestic batik. Many European manufacturers stopped producing imitation wax-resist cloth.

P. F. van Vlissingen & Co. needed to develop new markets. They began to diversify, exporting to countries like Japan and Sweden and later to Africa. One new initiative was to start producing printed kangas for the East African market.

Their main competitor, the Prévinaire company, was likewise trying to explore new markets while continuing to improve its wax-resist production process. In 1875 they renamed the company Haarlemse Katoenmaatschappij, the Haarlem cotton company, soon known as HKM.

In 1831 the Dutch on Java began recruiting West Africans for the military, offering them a six-year contract and a promise that they would be treated and paid on the same basis as the European troops (van Kessel 71). The initial target was to recruit 150, but only 44 arrived, mainly former slaves and debtors. The Dutch approached the Kingdom of Ashanti and began buying slaves and enlisting them for long periods of service – up to 20 years – contravening the international ban on the slave trade. In 1837 they signed a contact under which the Ashanti king Kwaku Dua I would supply 1,000 men per annum in return for 6,000 guns with powder. After expiry of their contracts, the recruits could re-enlist or take up permanent residence on Java. In fact, most chose to return to their native lands. After 1840 an increasing stream of West African soldiers began returning from service with the Dutch in the East Indies. They arrived home with gifts of batik, which quickly established itself as an exotic luxury product.

In 1876, Vlisco decided to export its imitation batik to West Africa, a convenient port of call on the outward voyage to Batavia. It appointed the well-established British merchant F. & A. Swanzy as a local distributor. Likewise HKM began to export to the Gold Coast on the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, which had by then become a British colony, using the Scottish trading agent Ebenezer Brown Fleming.

Coastal West Africa turned out to be a ready-made market. It seems that consumers had tired of earlier imported printed cottons and readily accepted the imitation batiks. It was not long before Haarlem designers began producing new patterns that were considered more appropriate to Gold Coast tastes.

In 1906 HKM automated the production process by applying the resin using a pair of synchronised engraved copper rollers rather than the outdated La Javanaise. The new process still replicated the crackling effects characteristic of batiks. Additional colours were added by hand using printing blocks, giving each textile its own character. P. F. van Vlissingen & Co. quickly responded by acquiring a duplex roller-printing machine of its own. By now it was becoming the largest cotton producer in the Netherlands (Ingenbleek 1997).

In 1911 a new Dutch-based competitor entered the wax print market. Having agreed to produce cloth for HKM a few years earlier, the textile manufacturer Ankersmit decided to begin selling to the Gold Coast through a local agent in competition with P. F. van Vlissingen & Co. However the latter had by now gained a firm foothold – in 1913 its wax prints were being sold through almost 30 different trading posts along the Gold Coast. The onset of war placed severe restrictions on exporters and HKM, being totally dependant on the African market, was forced to liquidate. Its assets and equipment, including five duplex roller resin-printing machines, were acquired by van Vlissingen, Ankersmit and the Leidsche Katoen Maatschappij. Van Vlissingen and Ankersmit had by then become the main producers of wax prints. Van Vlissingen & Co. simplified its name to Vlisco in 1927. Its printed cloth was by now widely known as 'Dutch Wax' or 'Wax Hollandais', and these names were adopted as trademarks. Vlisco was by now the dominant supplier of top quality wax-resist textiles to the West African market.

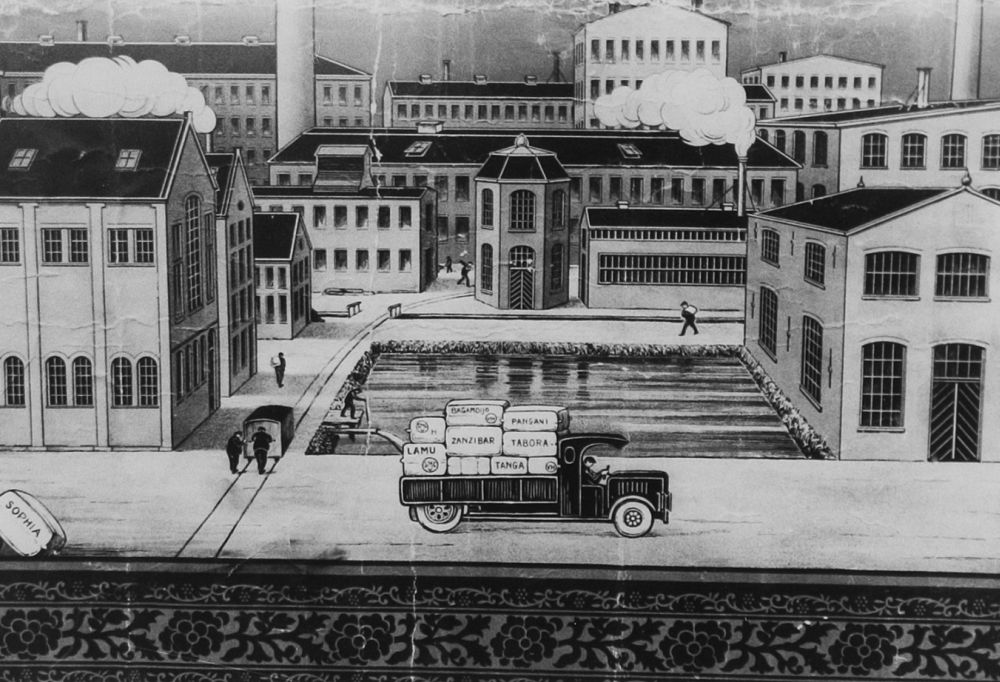

A drawing of the Vlisco works at Helmond with a lorry carrying shipments to Lamu in Kenya, Zanzibar, and Pagani, Tabora and Tanga in Tanzania

Although the Leidsche Katoen Maatschappij exported Java-style prints to West Africa, it failed to gain a foothold in the wax print market. It was hit hard by the world economic crisis of 1929 and in 1936 was liquidated.

Vlisco and Ankersmit remained the only significant wax-resist cotton print producers and were linked by numerous trade agreements. In 1956 they collaborated further by establishing a jointly owned dyestuffs factory, NV Gamma, located next to the Ankersmit chemical factory in Borgharen.

The African market experienced substantial growth after the Second World War. In 1957 the Gold Coast, Ashanti, the Northern Territories and British Togoland were unified as one single independent dominion within the British Commonwealth under the name Ghana. The French West African states of Cameroon, Togo, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso and the Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoir) followed in 1960, as did the British protectorate of Nigeria.

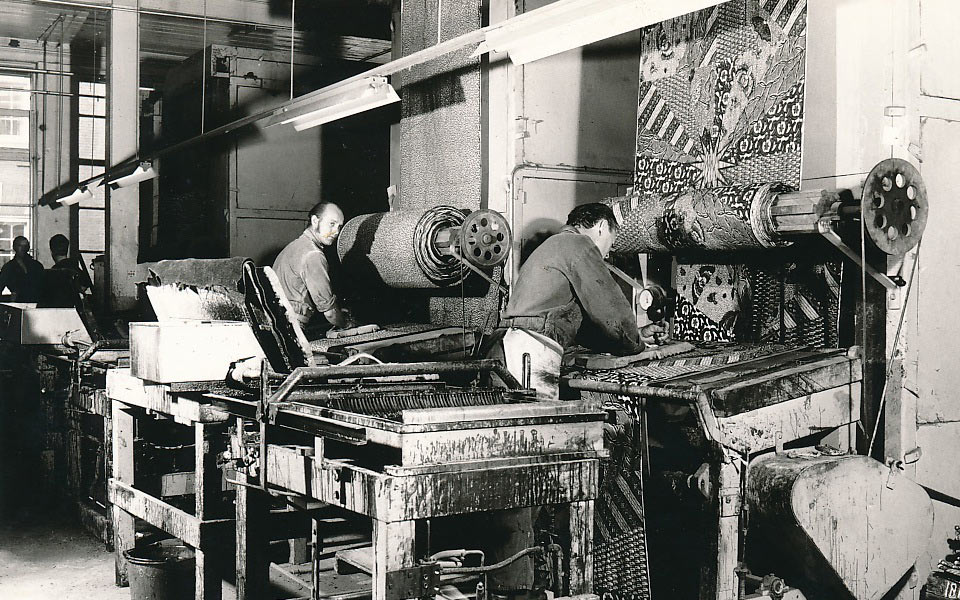

Hand block printing additional colours on wax printed cottons in the 1950s to 60s

Now the UK-Dutch consumer products giant Unilever was beginning to show an interest in the wax print industry, concerned that it might fall into foreign hands. This encouraged Vlisco to seek further cooperation with Ankersmit, and in 1962 they established the joint sales company Van Vlissingen Ankersmit Export Maatschappij (VAEM). Ankersmit’s poor financial results in 1963 resulted in its shareholders pressurising management to seek a merger and talks were held with Vlisco and the textile maker NV Stoomweverij Nijverheid Enschede (NV Steam Weaving). In 1964 the three companies merged and Ankersmit became a subsidiary of the newly formed company Texoprint. The company was formally established under the name Vlisco in 1965.

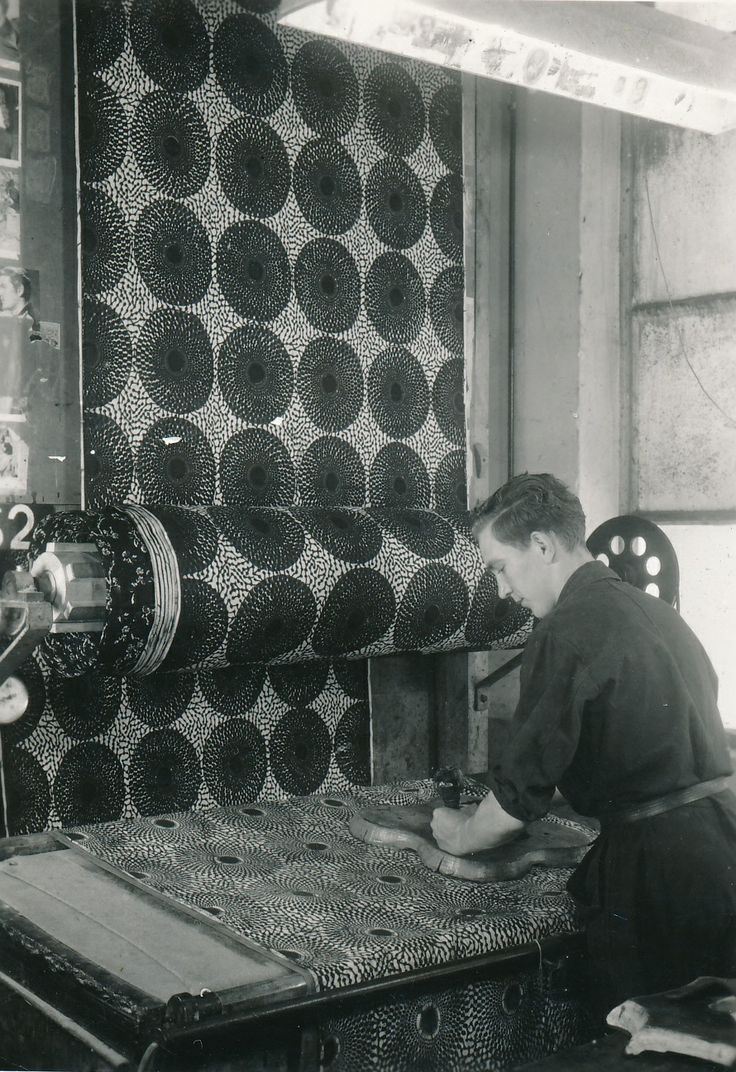

Manufacturing Plaque-Plaque in the Vlisco factory

After gaining independence many African countries were keen to establish local textile production plants, thus reducing their dependence on imports. Using Unilever’s African contacts, Vlisco began negotiating with local governments. In 1965 they established the Ghana Textile Printing Company as a joint venture with the Ghanaian government as well as Juapong Textiles Limited in the Ghanaian outback of Akosombo to make basic cotton cloth for factories in the Netherlands, Ghana and the Ivory Coast. In 1967 Vlisco formed another joint venture with the Ivory Coast government called UniWax, to produce cheaper fancy prints. These developments allowed Vlisco to gradually withdraw from the lower segment of the market and increasingly concentrate on higher quality wax prints.

For many decades Vlisco had faced the challenge of competing against lower priced copies produced in China. However because the quality of these fake cloths was poor they did not initially pose a major threat. Over time Chinese producers began to improve the product quality and to copy new designs with increasing speed. Vlisco decided that it not only needed to establish a strong brand identity, but also to protect it wherever possible.

Vlisco’s sales to the Ivory Coast, the Gold Coast, and Togo really took off during the 1960s and 70s. Branded ‘real Dutch wax’, the cloth gained cultural significance as a symbol of nationalist revival in the wake of political independence. Togo became a highly successful centre thanks to a group of female textile merchants in the capital of Lomé, who distributed the cloth along the entire West African coast as le wax hollandaise. They had become wealthy women and were labelled the ‘Mama Benz’ or ‘Nana Benz’ because some were chauffeured around in Mercedes Benz limousines.

In 2003 Vlisco embarked on a strategy of reorganisation called ‘Fighting the Dragon’ in response to increasing loss of market share to cheaper Chinese wax print textiles, many based on copies of Vlisco designs. This involved becoming more responsive to rapidly changing African tastes, forcing local distributors to become exclusive, opening flagship retail outlets in the main West African cities and intensifying the promotion and advertising of the Vlisco brand.

A Vlisco billboard in Lomé, Togo, in 2014

In 2010 Vlisco was acquired for $151 million by the London-based private equity company Actis. It was at that time designing, manufacturing and distributing 50 million metres of branded cloth per annum, primarily to West and Central Africa, and was employing over 2,100 people, 1,500 of whom were based in West Africa. For Actis, this was seen as a unique opportunity to invest in a brand-oriented company targeting the growing African middle classes.

The Vlisco site in Helmond today

Today Vlisco fabrics are regarded as a symbol of African pride, seen as African cloth, despite being designed and produced in Holland. Ironically, despite its huge success, the company remains virtually unknown in its own domestic market.

A huge range of Vlisco wax prints on sale in Sonna African Textiles, Spitalfields, East London

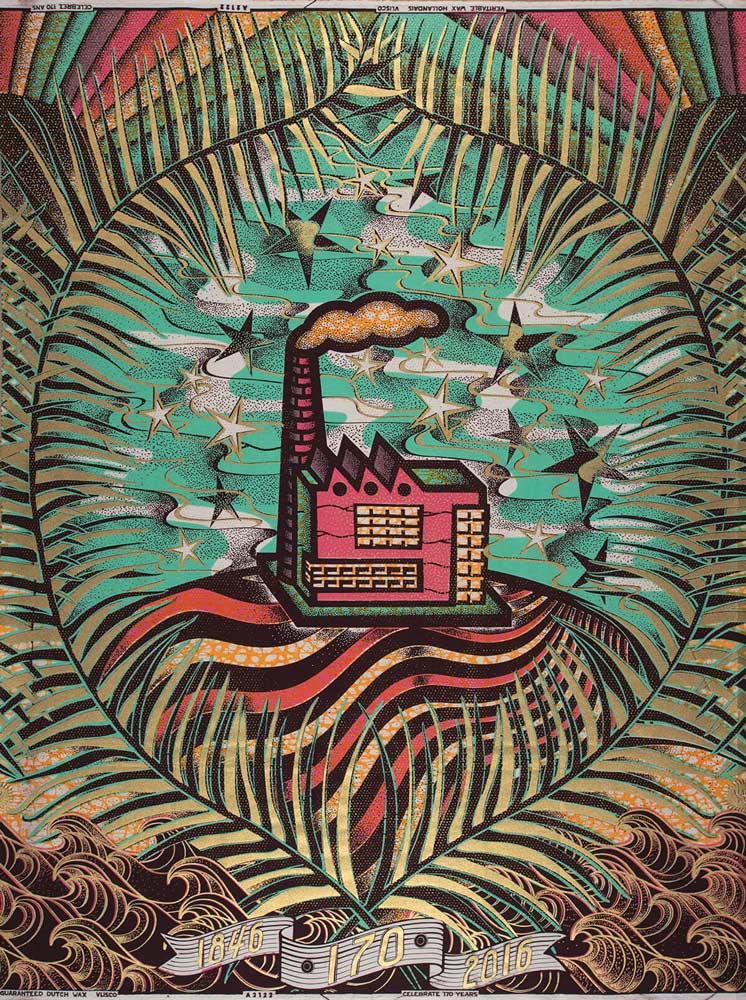

A limited edition Vlisco Wax Hollandais released in 2016 to celebrate the company’s 170th anniversary

Return to Top

The Manufacturing Process

The wax-resist technique used to make Indonesian batik involves applying a wax pattern to a cotton textile using a pen or printing block in order to resist the dye. After dyeing the wax is removed by immersing the cloth in boiling water. The wax resist maintains the original undyed colour of the underlying cloth, thus creating the pattern.

The mechanised version of this approach is known as mechanical wax-resist. While Vlisco’s complex production process is a closely guarded secret it is believed to involve some 27 separate stages.

In summary a synthetic resin is first applied to the cloth using duplex copper rollers. Then the base colour is applied by immersion in a dye bath, only some of which adheres to the unwaxed areas of the cloth. Then in the ‘breaking-off’ stage, part of the resin is removed in an industrial washing machine, partially using mechanical agitation, leaving the remaining resin to coalesce into small spheres. These act as a second resist for the second dyeing stage using a different colour.

Engraved printing cylinders in the GTP factory at Tema in Ghana

This partial removal process not only creates the characteristic bubbling effect of Dutch wax but the residual resin forms micro-cracks that produce a blurred effect as the second colour is fitted to the base pattern. Following the second dyeing, the residual resin is removed using trichloroethylene solvent, which is subsequently recycled.

Subsequent colours can be fitted to the design using roller printers. Stages of this process can be repeated to create a plethora of colours and designs.

Unfortunately trichloroethylene is not only harmful to health, but is also carcinogenic. Although Vlisco has sought to find alternatives, none have been found so far. In 2013 Vlisco sought EU authorisation to continue using the solvent under the REACH Regulation (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) and this was eventually approved in 2015.

Processing wholesalers orders from finished product at Vlisco in Helmond

Vlisco produces several types of Dutch wax-resist printed cottons with different levels of quality and price.

The simplest wax prints are made with the base colour, the wax motifs and the second colour applied mechanically, but with additional colours applied by hand using printing blocks. These cheaper versions of the wax print were introduced into the West African market in the 1930s, but after Vlisco opened plants in Ghana and the Ivory Coast in the 1960s production was transferred from Helmond to the new West African factories

The wax prints known as Wax Hollandais are made with the base colour, the wax motifs and the second colour applied mechanically. After the wax is broken mechanically to create the natural cracked and bubbling batik effect, the next colour is applied mechanically but without the use of wax.

The finest quality wax prints are branded Super-Wax and are made using an extra densely woven, fine cotton fabric. Super-Wax always features two blocking colours displaying the natural crackling effect. A third colour may be added but without this crackling effect.

In its African plants Vlisco manufactures Java prints, also known as fancy prints, but these are not wax prints. They are simply cottons that have been roller printed, a process that allows very fine and detailed motifs to be reproduced in a variety of colours.

Return to Top

Some Examples of Vlisco Patterns

During its past 174 years of trading, Vlisco has created an incredible 350,000 original fabric patterns. For comparison, ABC Wax has only produced 35,000 patterns.

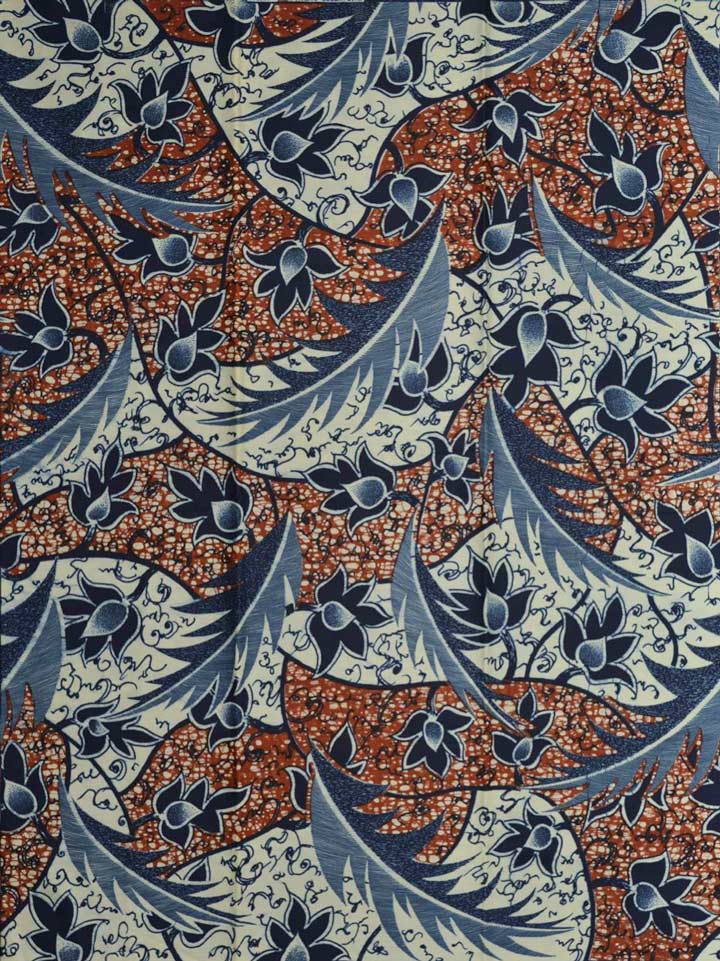

A few still echo the patterns of traditional Javanese batik, such as an example from our collection whose colours resemble the natural indigo and soga brown-dyed cloths of the past.

Above and below: A Dutch Wax Hollandais from Vlisco's 'New Collection', pattern number VL116075. Richardson Collection.

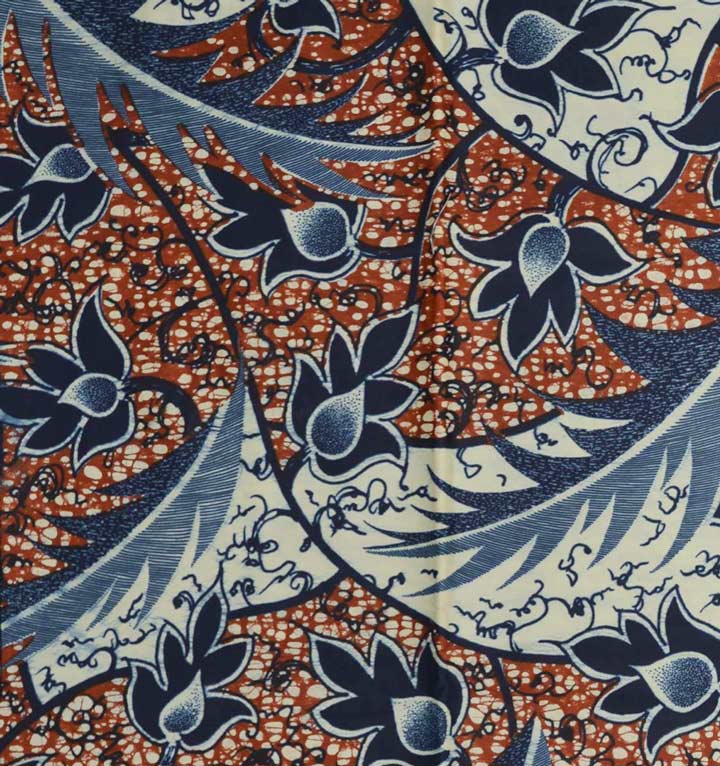

Of the two Javanese-like examples shown below, the first is embellished with gold shimmer on one side like a prada batik, and the second is based on the Javanese twin-patterned pagi-sore batik.

Wax Hollandais Limited Edition VL40550.100

Day and Night (Wax Hollandais VL00006.177)

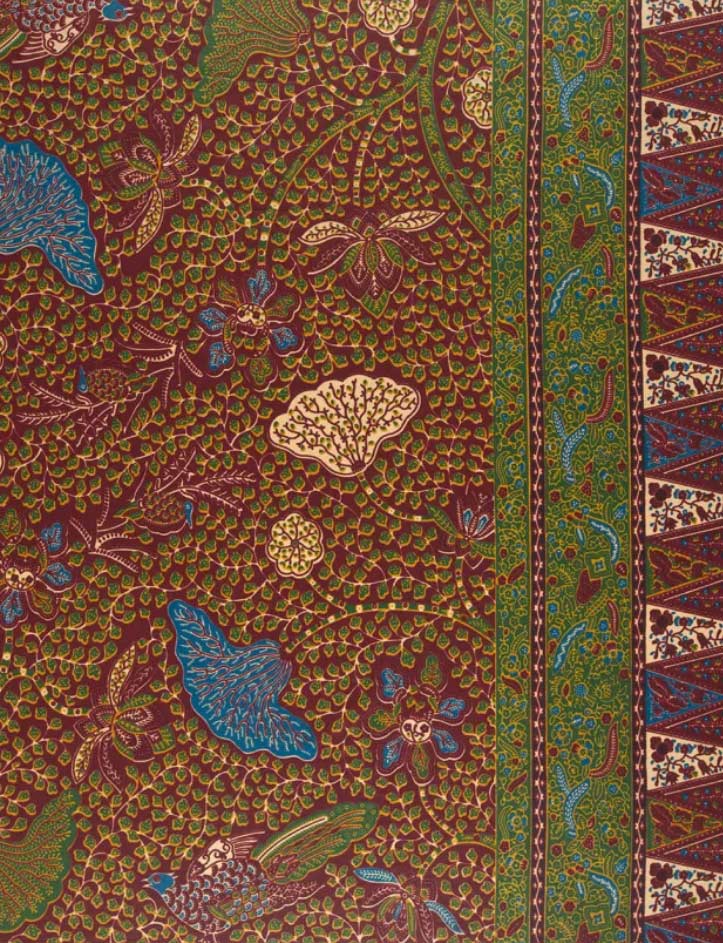

The Good Living pattern is based on the batiks that had very strong saturated colours and were made by the Chinese in Pekalongan in Central Java. This was originally released 75 years ago and became very popular in Ghana. It was revived for the Ivorian market in 2008 when its launch coincided with the broadcast of a popular TV show about the daughter of a gardener. It therefore became known there as La Fille du Jardinier.

Good Living (Java VL0731R.023)

In Africa many of these patterns are seen as having a deeper meaning – many serve an important function in attributing a certain status to the wearer. Fancy prints, wax block prints and particularly genuine wax prints signify that the wearer is wealthy and successful. More importantly, they have the power to convey messages that cannot be communicated with words. Many are given names and meanings by the local female traders who sell them. Some are named after sayings, personalities or occasions. By wearing a specific wax print, the wearer can warn, question, insult, complain, belittle but also comfort.

Thus the Alphabet pattern, which was created in 1920, was mainly worn by women who went to a colonial school and could read, write and count. It implied that the owner was a literate and an educated person. Modern reinterpretations of this design have patterns in which blackboards are replaced with computers.

Alphabet (Wax Hollandais VL00017.019)

The Awoulaba pattern became popular in the 1980s and coincided with the launch of a beauty contest called Miss Awoulaba in Abidjan. In the Baoulé language of the Ivory Coast, Awoulaba means Queen of Beauty and is applied to women with generous curves.

Awoulaba (Wax Hollandais VL03988.019)

According to Vlisco, the Santana Wax Hollandais pattern is popular with the Ebo or Igbo of south-central and south eastern Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea. The pattern is named after Madame Santa Anna Nelly, one of the Nana Benz in Togo who apparently was given exclusive rights to sell this pattern, which is based on a sketch provided by the cloth sellers. It is said to represent an angry woman lying in bed with her back to her husband who is asking forgiveness and begging her to turn around, saying Cherie, ne me tourne pas le dos (Darling, don’t turn your back on me).

Santana or Darling don’t turn your Back on Me (Wax Hollandais VL03686.024)

If a woman believes that her husband is cheating on her and she is afraid to raise the issue with him, she can buy the design shown below and wear it. In doing so she is sending a coded message to her husband, notifying him that she knows he has been unfaithful.

The Ungrateful Husband pattern

A similar message is conveyed by the pattern variously known as Love Bomb, Wounded Heart, Cœur Blessé or Dynamite. In Togo this pattern symbolises the state of mind of a woman who knows her husband is cheating on her and is leaving her with a Cœur Blessé or broken heart.

The Love Bomb pattern (Wax Hollandais A0203)

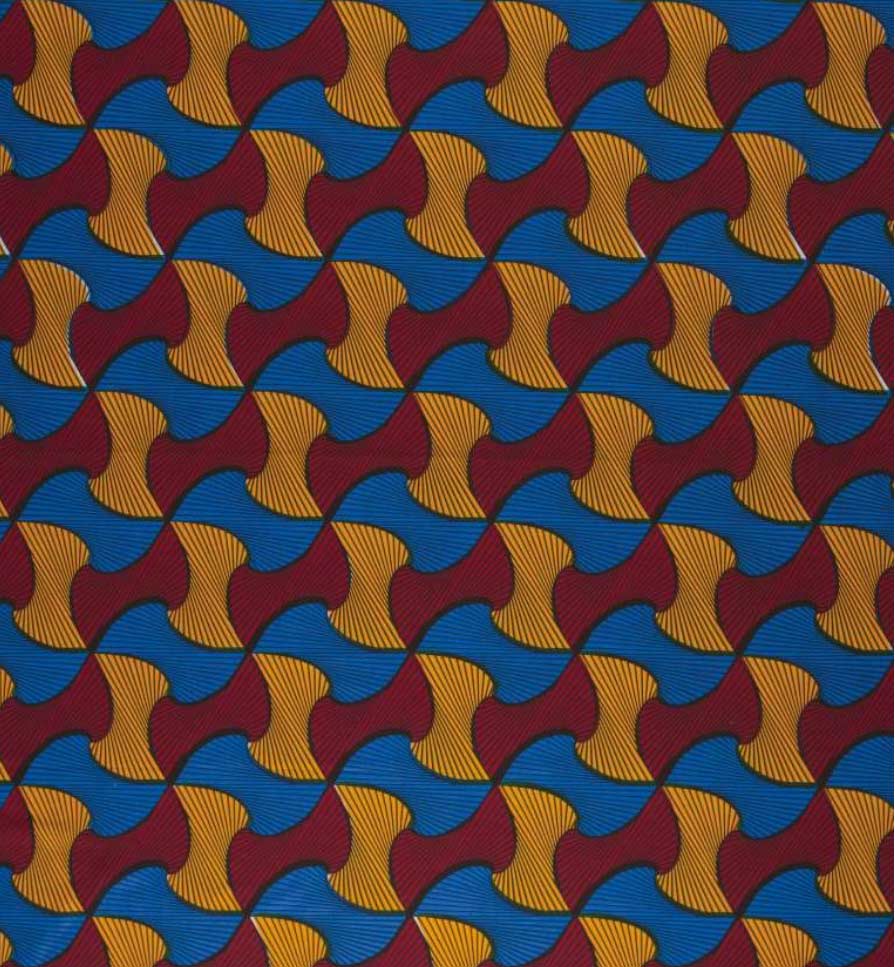

The next pattern is known as Eyes in Nigeria and either L’Oeil de Boeuf (Bull’s Eye) or Lisu ya Pité (Lustful Eye) in the Ivory Coast. Apparently a woman wears it if she wants to show a man that she desires him.

Eyes or Lustful Eye (Wax Hollandais VL00760.053)

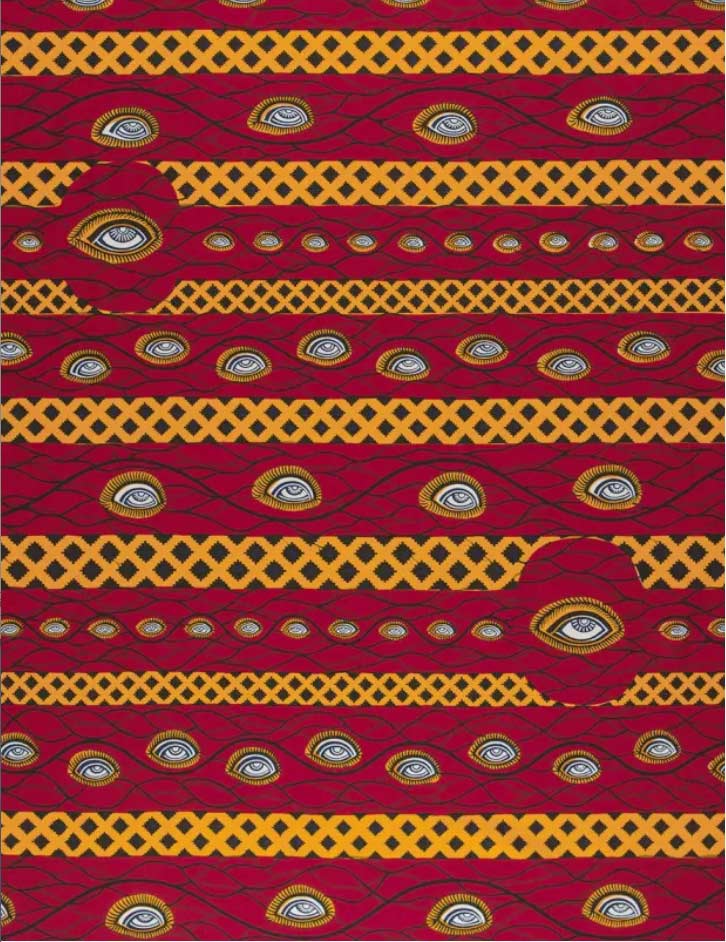

La Famille or The Happy Family pattern symbolises the archetypical African family and the pivotal role of women within it. The central hen represents the maternal figure of the mother surrounded by her chicks and future chicks, the eggs. The rooster is the troublesome father and only his head is shown.

La Famille or The Happy Family (Wax Hollandais VL0H628.064)

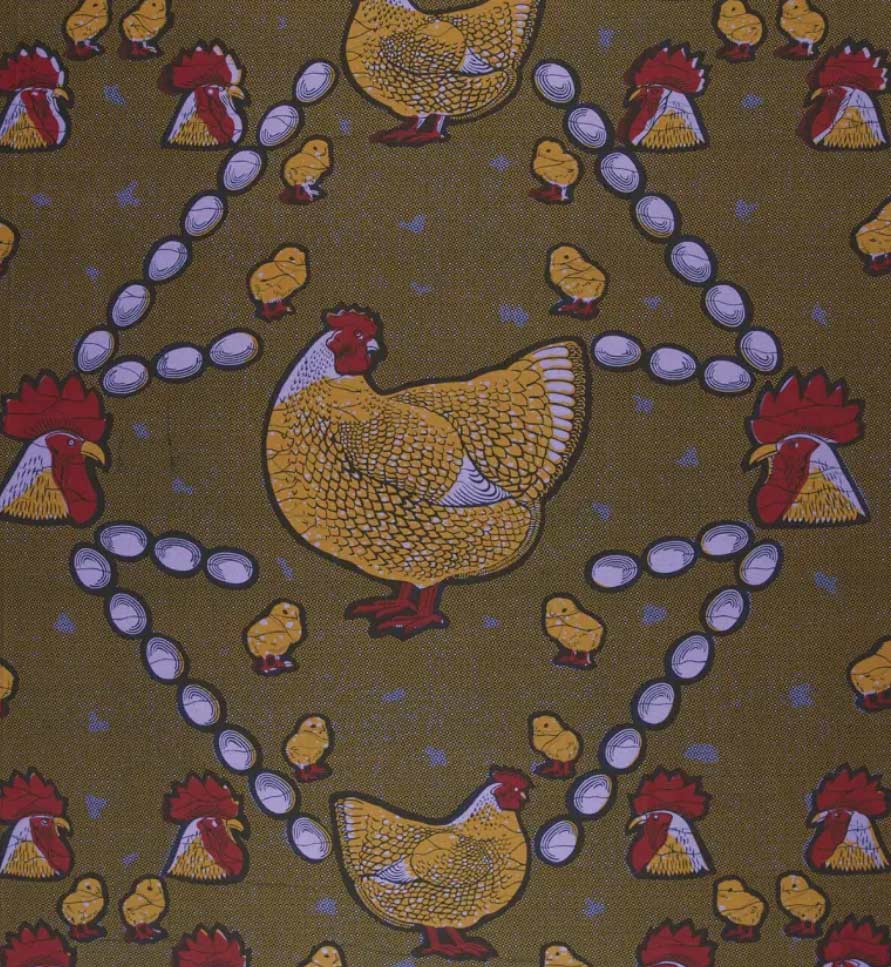

The Mama Benz pattern is a humorous reference to the Mama Benz (also known as Nana Benz), the female vendors of Vlisco products in Africa.

Mama Benz (Wax Hollandais VLA1224.005)

Several patterns were based on important state visits to Africa. In 1956 the recently crowned Queen Elizabeth II paid her first visit to Nigeria, at that time still a British protectorate. It is believed that copies of this print were given away to ensure the welcoming crowd gave the Queen a warm welcome

Queen Elizabeth II

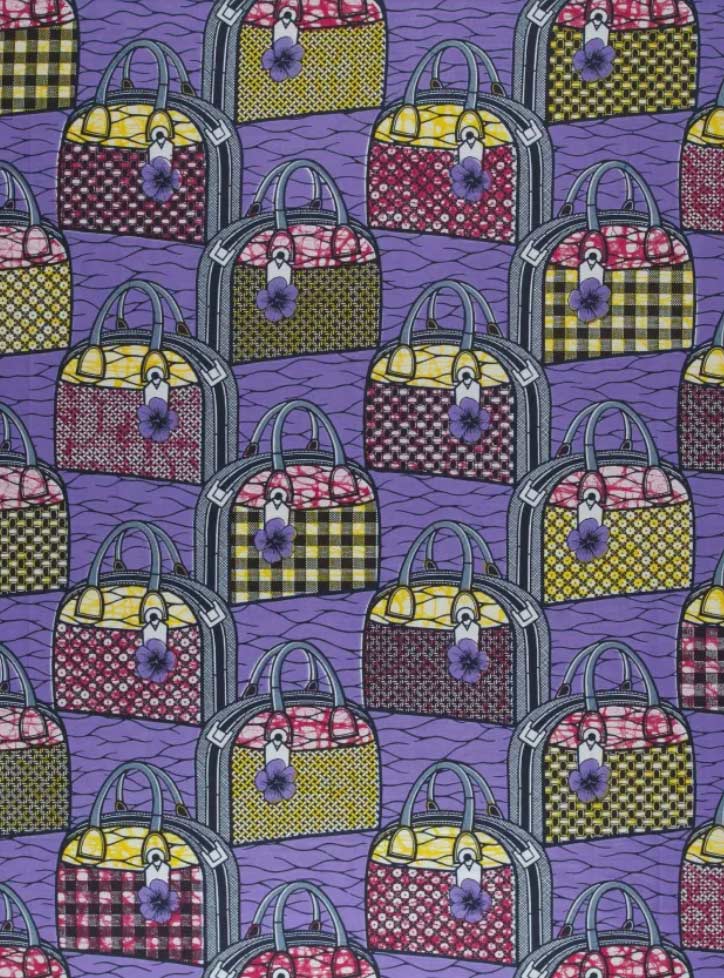

The Michelle Obama's Handbag pattern was released in 2011, the year in which the First Lady first visited Africa. Vlisco claim the bag is similar to the one Michelle Obama carried as she descended the steps of Air Force One. Made from Super Wax, which is softer, thinner and has an extra colour, wearing this more expensive fabric symbolises prestige.

Michelle Obama’s Bag (Super Wax VLA1106.087)

Return to Top

Bibliography

Ankersmit, Willem, 2010. The waxprint: its origin and its introduction on the Gold Coast, Masters Thesis, Leiden University.

Bruggeman, Danielle, 2017. Vlisco: Made in Holland, adorned in West Africa, (re)appropriated as Dutch design, Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 197-214.

Delhaye, Christine, 2019. The Production of African Wax Cloth in a Neoliberal Global Market Vlisco and the Processes of Imitation and Appropriation, Fashion and Postcolonial Critique, pp. 246-280, Sternberg Press, Berlin.

Edoh, Amah Melissa, 2016. Doing Dutch Wax Cloth: Practice, Politics, and “The New Africa”, Doctoral Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston.

Grosfilley, Anne, 2018. African Wax Print Textiles, Prestel, Munich.

Hemmings, Jessica, 2015. Dutch wax-resist textiles: Roger Gerards, creative director of Vlisco, in conversation with Jessica Hemmings, Cultural Threads: Transnational Textiles Today, pp. 66-91, Bloomsbury, London – New York.

Hoogenboom, Marcel; Bannink, Duco and Trommel, Willem, 2007. ‘Fighting the Dragon’ – The Reorganization of a Textile Printing Company in The Netherlands and West Africa, Internal working paper, WORKS project

Hoogenboom, Marcel; Bannink, Duco and Trommel, Willem, 2010. From local to global, and back, Business History, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 932–954.

Kessel, Ineke van, 2012. Labour migration from the Gold Coast to the Dutch East Indies: Recruiting African troops for the Dutch colonial army in the age of indentured labour, Fractures and Reconnections: Civic Action and the Redefinition of African Political and Economic Spaces, pp. 61-86, Lit Verlag, Zurich.

Nabholz-Kartaschoff, Marie-Louise, 2019. Original or Imitation? Batik in Java and Glarus (Switzerland) in the Nineteenth Century, The Textile Museum Journal, vol. 46, pp. 190-209.

Ruschak, Silvia, 2016. The gendered luxury of wax prints in South Ghana: A local luxury good with global roots, Luxury in Global Perspective: Objects and Practices, 1600–2000, pp. 169-191, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Spencer, Clare, 2020. Wax print: Africa'a pride or colonial legacy?, BBC News, London.

Sylvanus, Nina, 2016. West Africans ditch Dutch wax prints for Chinese ‘real-fakes’, The Conversation, UK.

Verbong, G. P. J., 1991. Coloristen en laboratoria: de ontwikkeling van het coloristische werk in de Nederlandse textielveredelingsindustrie, Tijdschrift voor de geschiedenis der geneeskunde, natuurwetenschappen, wiskunde en techniek, vol. 9, issue 4, pp. 216-231.

Vlisco official website.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 24 January 2021.